Abstract

Managed care pharmacists apply real-world evidence (RWE) to support activities such as pipeline forecasting, clinical policy development, and contracting for pharmaceutical products. Managed care pharmacy researchers strive to produce studies that can be applied in practice. While asking the right research question is necessary, it is not sufficient. As with all studies, consumers of RWE look for internal and external validity, as well as sources of bias, to determine how the study findings can be applied in their work. To date, however, some of the safeguards that exist for clinical trials—such as public registration of study protocols—are lacking for RWE. Several leading professional organizations have initiatives dedicated to improving the credibility and reliability of such research.

One component common to these initiatives is enhanced transparency and completeness of methodologic reporting. Graphical representations of study designs can improve the reporting and design of research conducted in health care databases, specifically by enhancing the transparency and clarity of often complex studies. As such, Schneeweiss et al. (2019) proposed a graphical framework for longitudinal study designs in health care databases. Herein, we apply this framework to 2 studies published in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy that represent common research designs and report how application of the framework revealed deficiencies in reporting. We advocate for adoption of this framework in the effort to increase the usability of RWE studies using health care databases by managed care pharmacy.

Managed care pharmacists apply real-world evidence (RWE) to support a wide range of activities, yet a lack of methods transparency in RWE studies limits its use.1 Today, several leading professional organizations are working to advance the credibility and reliability of RWE, and enhancing transparency of reporting is a common component to each initiative.2-8 Because the RWE study designs that have been conducted using longitudinal health care databases are complex, graphical representation of study designs can improve the reporting and transparency of methods. Accordingly, Schneeweiss et al. (2019) proposed a graphical framework for longitudinal study designs in health care databases.9 In this article, we apply this framework to 2 studies published in the Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy (JMCP) that represent commonly used research designs. We also discuss the implications of the framework application for the managed care pharmacy reader, as well as considerations for journals and their editors.

How Are Payers Using Real-World Evidence?

As the field of RWE has expanded, researchers have attempted to quantify how managed care pharmacy uses RWE in business practices. Multiple surveys have confirmed a strong and sustained preference for clinical trials over RWE, particularly for coverage decisions by pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) committees and comparative-effectiveness data.1,10-12 Further, RWE is infrequently cited in P&T committee monographs.13 By definition, RWE is the clinical evidence of a medical product derived from analysis of data related to patient health status and/or the delivery of health care collected from a variety of sources.14 Thus, RWE is only generated after a product has been on the market and is not available at the time of initial formulary review, which is required within 90 days of product launch for Medicare.

So, if managed care pharmacy prefers clinical trials for formulary decisions, how are payers using RWE, if at all? A qualitative research study by the University of Arizona and the National Pharmaceutical Council revealed that the most common use of RWE is for utilization management, followed by tiering patient cost sharing, and then formulary placement (reported as “sometimes” by 74%, 63%, and 58% of participants, respectively).1 Practically, this means that RWE serves as a differentiator between products or for determining appropriate prior authorization criteria or step therapy. However, it also means that use of RWE by payers in these activities is not high. The percentages reported above were for responses of “sometimes,” whereas only 5%-11% of respondents selected “often” or “almost always.” In the same survey, 42% of respondents reported that nontransparent methods were a barrier to use of RWE.

However, only considering managed care pharmacy’s use of RWE in the setting of formulary policies misses many other business practices. Managed care pharmacy encompasses a wide range of activities beyond formulary design, including drug contracting, quality measurement and reporting, pharmacy network management, and patient safety programs, for example.

Value-based contracting relies on RWE and is defined as a contractual agreement in which the payment terms for a product are tied to agreed-on clinical circumstances, patient outcomes, or measures.15 The very nature of these contracts measures product performance using RWE, effectively seeking to “prove” the product’s benefits observed in clinical trials or the proposed value proposition. Published survey work with payers and manufacturers has shown that barriers to value-based contracts include the inability to obtain accurate outcome measures and a lack of transparency, among others.16,17 With respect to transparency, 1 payer was quoted as stating, “Small plans don’t have as many resources to validate and replicate the modeling done by the pharma company to determine the rebate amounts, additional transparency is needed.”17 This statement underscores that plans often prefer to replicate analyses using their own data, which may be due in part to a lack of trust in the evidence being presented to them.

Like value-based contracting, quality measures are effectively measures of RWE. Health plans, pharmacy benefit managers, and pharmacies are accountable for a myriad of quality measures determined or developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Pharmacy Quality Alliance, and others. Performance on these quality measures has substantial implications on financial performance and ultimately membership enrollment and patient access. RWE also supports the development and refinement of patient safety programs. Such programs are often designed based on findings from the published literature. As such, transparency of methods is crucial to reproducibility of outcomes.

Initiatives to Increase the Credibility and Reliability of RWE

The 21st Century Cures Act requires the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to establish a program to evaluate RWE for new drug indications and to support postapproval requirements.18 Because the FDA will consider reporting requirements for observational studies as a part of the Cures Act, a joint task force of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research and the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology published 2 statements on enhancing the transparency and reproducibility of RWE studies.2-5 The first focuses on hypothesis-testing studies and recommends public registration of the hypothesis and analysis plan and attestation to conformance with or deviation from the original analysis plan, among other recommendations.2,3 The second focuses on reproducibility and provides a reporting table that can be implemented by researchers to enhance the reproducibility of their work.4,5

Similarly, the National Pharmaceutical Council (NPC) and Academy Health released a white paper with recommendations aimed at increasing the usability of RWE by payers, and the 2 organizations have a peer-reviewed publication under review at the time of this writing.7 Recommendations from NPC/Academy Health include prespecified hypotheses and analyses plan logged in a repository, feasibility assessment of data for the research question, completion of sensitivity analyses on key definitions and outcomes, and provision of data coding and summary tables upon request.

In 2017, the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, together with the Office of Health Economics Research, published a report from their annual Member Policy Summit on the opportunities and challenges for RWE for coverage decisions.8 Like other recommendations, this report proposes a mandatory registry for observational studies that would include study analysis plans.

While this is not an exhaustive description of all ongoing initiatives, each of these share a common element of advancing the transparency of methods reporting for RWE research.

Graphical Depiction of Longitudinal Study Designs

Consistent with the most recent RECORD-PE (REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely collected health Data for pharmacoepidemiology research) guidance for reporting on database studies and consensus statements from 2 leading professional societies favoring graphical representation, Schneeweiss et al. proposed a graphical framework for longitudinal study designs in health care databases.2-5,9,19 Described in detail in the Annals of Internal Medicine, this framework aggregates key temporal anchors into a single figure: source data range, study period, cohort entry date, outcome event date, washout window for exposure and outcome, exclusion assessment window, covariate assessment window, exposure assessment window, and follow-up window. In contrast to randomized controlled trials where randomization is the anchor date, nonrandomized database studies are anchored to the cohort entry date, which will vary for each patient in the study population. Further, because database studies rely on events that happen in the natural course of patient care, windows of time are used for secondary temporal anchors, such as washout windows and covariate assessment windows. As such, the proposed graphical framework is constructed around the cohort entry date, with all windows for secondary temporal anchors depicted relative to the cohort entry date. This resulting graphical framework displays sufficient detail to enable reproducibility yet is simple, unambiguous, and intuitive for the reader.

Application to Managed Care Pharmacy Research

JMCP published 84 RWE studies in 2018, which represented over three fourths of our original research articles. Of these, only 42% included a graphical depiction of the research study design, despite recommendations in author instructions to do so. To consider practical implications, we attempted to develop the proposed graphical study design for 2 studies recently published in JMCP that represent commonly used study designs.

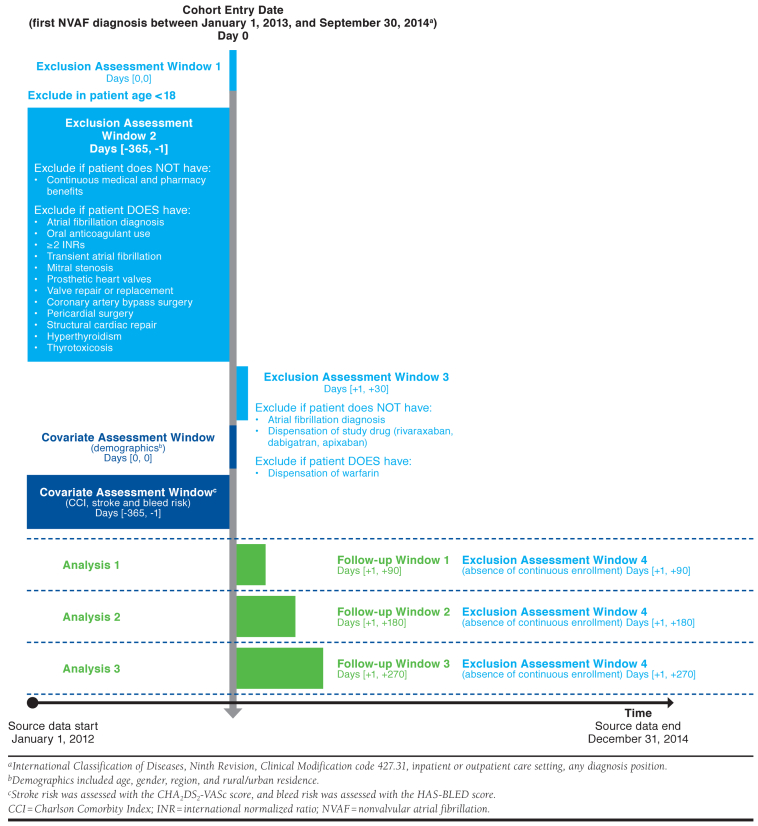

Brown et al.’s study (2017) compared adherence and treatment patterns for non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation using the Truven Health Analytics (now IBM) MarketScan administrative claims database.20 The authors used a number of inclusion and exclusion criteria, some of which relied on washout periods, age restrictions, and continuous enrollment requirements in the pre- and post-index periods. While these elements were reported in the Methods section, the full description of the study design and study measures are spread over multiple paragraphs and headings. When adapting the written methods to a standardized graphical format (Figure 1), we identified some ambiguities, including an unclear assessment window for the Charlson Comorbidity Index, unclear timing of assessing patient age for an exclusion criterion, and discrepancies between textual exclusion criteria and the flowchart. The study also applied a complex follow-up period, with adherence outcomes assessed in 3 different cohorts, which was made more clear visually.

FIGURE 1.

Study Design for Brown et al.20

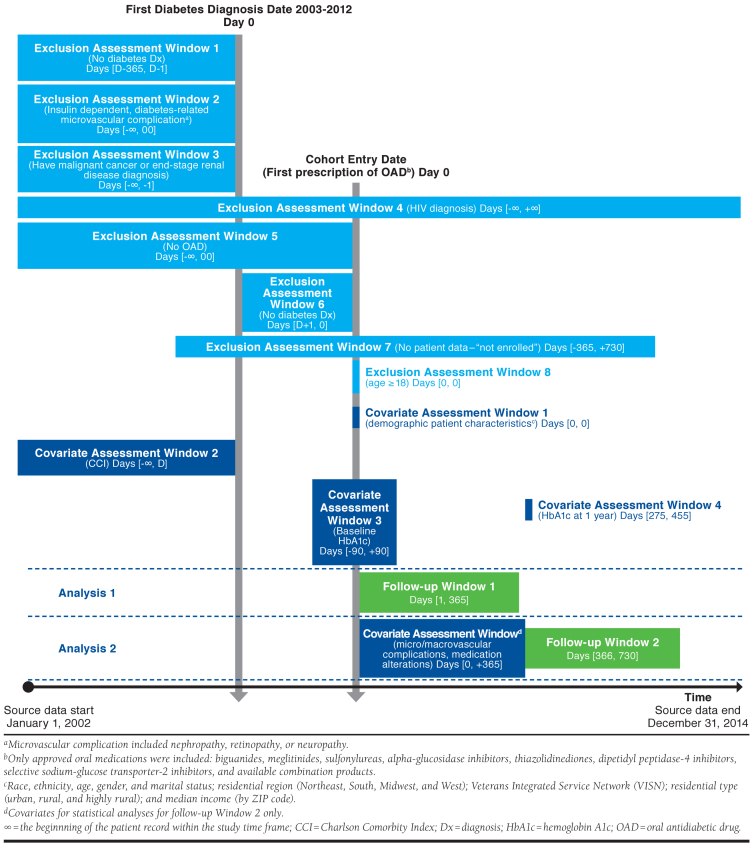

Gatwood et al. (2018) evaluated variables associated with nonadherence to oral antidiabetic therapy and changes in adherence patterns in the first 2 years of oral antidiabetic therapy using the Veterans Affairs Corporate Data Warehouse.21 Similar to the Brown study, the Gatwood study had several inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and covariates assessed over at least 13 different time periods relative to the index date for cohort entry, which we found easier to comprehend via graphical design visualization compared with the published text and attrition figure (Figure 2). We identified some ambiguities with the Methods text when developing the graphic, including unclear temporality of the diabetes diagnosis and first oral antidiabetic drug use, missing definition of medication alteration covariate and “necessary clinical data,” discrepancies between textual exclusion criteria and the appendix, and an unclear assessment window for the Charlson Comorbidity Index and the year 1 hemoglobin A1c.

FIGURE 2.

Study Design for Gatwood et al.21

The proposed study design graphics would not entirely replace the corresponding text in either study; however, efficiencies do exist. We conservatively estimated that 250 words could be extracted from the Methods sections, corresponding to 6.5% of the total word limit of 4,000 required by the journal. Further, the new graphical depiction of the study design cannot replace any of the tables or figures from the original paper. Both studies report a study attrition table in a second appendix. While it is not plausible to merge these 2 figures into 1 figure because of the complexity of the inclusion and exclusion criteria in these studies, it may be possible for some other studies.

While neither of these articles are lacking in quality, graphical representation would have likely made these articles clearer to readers and may have enhanced the overall design if used by the authors early in the study planning period.

Implications for the Managed Care Pharmacy Reader

We have established that managed care pharmacy uses RWE to differentiate products for utilization management, contracting, quality measurement, and safety programs; yet, transparency is a barrier to extensive use. As such, the proposed graphical depiction of study designs is one way to increase transparency of methods and has the potential to increase use.

In addition, pharmacy benefit managers and health plans are increasingly migrating from being consumers of research to becoming producers of research. Executive titles such as chief research officer and chief analytics officer are becoming more prevalent in the industry, as research organizations are proliferating: Anthem’s HealthCore, Aetna’s Healthagen, Express Scripts Lab, BCBS Alliance for Health Research, Humana Health Research, and Optum Health Economics and Outcomes Research, for example. These companies form alliances with leading academic institutions, pharmaceutical manufacturers, government organizations, and nonprofits to conduct health services research either for internal business or external consumption through published academic research or white papers.

Associates with master’s degrees and doctorates who conduct these analyses and studies have been trained in academic programs that emphasize the use of methods that have been validated in the peer-reviewed literature. Efforts to increase the transparency of methods of published research increases the ability of these teams to reproduce a study in a population of interest. Reproducibility is important because of the variability of populations represented in longitudinal health care databases. For example, a Medicaid database will differ greatly from a Medicare Advantage plan database in terms of population age, population density, health conditions, socioeconomic status, and social determinants of health. Similarly, a commercial health plan database with members from the Midwest will differ from a commercial health plan database with members from the South.

Considerations for Journals and Editors

A survey of editors of peer-reviewed journals revealed favorable views of studies using RWE.22 A common practice among journals is to impose word limits and restrictions on the number of words and number of tables and figures in a manuscript. A cursory review of health services research journals revealed common word limits of 3,000-5,000 words and up to 5 combined graphics, with various allowances for appendices/supplemental materials. Specifically, JMCP has 2 article categories for longitudinal studies of health care databases: research articles and research briefs. Research articles report experimental or observational studies using the scientific method and are limited to 4,000 words, 5 combined graphics, and 2 appendices. Research briefs differ in that they are not hypothesis-testing studies, but rather are descriptive in nature. Research briefs are limited to 2,500 words, 2 combined graphics, and no appendices. Given these current limits, it would be nearly impossible for authors of research briefs to add a study design graphic. As such, the editorial team is reviewing the JMCP policy regarding limits.

Word and graphic limits do, however, serve an important purpose. Limits aid in allocation of limited resources that journals face, including number of print pages and copyediting and layout resources. Limits also force authors to be parsimonious in reporting—research articles are not intended to be dissertations after all. The average reader likely appreciates length restrictions, as does the peer reviewer who volunteers his or her time to advance scientific discourse.

Given the case we have presented for inclusion of a detailed study design graphic, it is clear that journal editors face a challenge of balancing the need for transparency with their resource constraints and reader preferences. One potential solution to this challenge is increasing the practice of online supplemental materials. This allows authors to share more details of their work, yet only interested readers can choose to access the information. However, questions remain about how to best operationalize this. Should the supplemental materials be housed on the journal’s webpage or the author’s? Should the supplemental materials be copyedited and laid out by the journal staff or posted as submitted? Should there be a limit on the length of supplemental materials? None of these decisions are insurmountable, but as with all decisions, they have trade-offs. The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors recommends that supplementary electronic-only material be submitted for peer review but gives little other guidance. Nonetheless, unlimited supplementary materials may impose a burden for peer reviewers and should be considered cautiously.

Conclusions

The editors and the Editorial Advisory Board for JMCP continuously look for means to improve the usability of articles published in the journal by our readers. As such, we recommend the use of the described graphical framework. While no requirement is being recommended at this time, we encourage authors to consider making these detailed graphical representations part of their submission to JMCP, either as a figure in the main paper or as an appendix. Further, the editorial team is reviewing the policy on table/figure limits and supplementary material to determine what modifications can help improve reporting transparency. Our aim of such quality improvement work for the journal is to enhance the insights and decision-making process gleaned from our published research by the managed care pharmacy community.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malone DC, Brown M, Hurwitz JT, Peters L, Graff JS. Real-world evidence: useful in the real-world of us payer decision making? How? When? And what studies? Value Health. 2018;21(3):326-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger ML, Sox H, Willke RJ, et al. Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: recommendations from the Joint ISPOR-ISPE Special Task Force on Real-World Evidence in Health Care Decision Making. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1003-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger ML, Sox H, Willke RJ, et al. Good practices for real-world data studies of treatment and/or comparative effectiveness: recommendations from the joint ISPOR-ISPE Special Task Force on Real-World Evidence in Health Care Decision Making. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(9):1033-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang SV, Schneeweiss S, Berger ML, et al. Reporting to improve reproducibility and facilitate validity assessment for healthcare database studies v1.0. Value Health. 2017;20(8):1009-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang SV, Schneeweiss S, Berger ML, et al. Reporting to improve reproducibility and facilitate validity assessment for healthcare database studies v1.0. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(9):1018-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Framework for FDA’s real-world evidence program. December 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/120060/download. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 7.National Pharmaceutical Council and Academy Health. Real-world evidence methods transparency. White paper. Available at: https://www.npcnow.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Real-world%20Evidence%20Methods%20Transparency.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 8.Hampson G, Towse A, Dreitlein B, Henshall C, Pearson SD. Real world evidence for coverage decisions: opportunities and challenges. A report from the 2017 ICER membership policy summit. March 2018. Available at: https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ICER-Real-World-Evidence-White-Paper-03282018.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Schneeweiss S, Rassen JA, Brown JS, et al. Graphical depiction of longitudinal study designs in health care databases. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(6):398-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi Y, Navarro RP. Assessment of the level of satisfaction and unmet data needs for specialty drug formulary decisions in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(4):368-75. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung MY, Halpern MT, West ND. Pharmaceutical technology assessment: perspectives from payers. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(3):256-64. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.3.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moloney R, Mohr P, Hawe E, Shah K, Garau M, Towse A. Payer perspectives on future acceptability of comparative effectiveness and relative effectiveness research. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2015;31(1-2):90-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hurwitz JT, Brown M, Graff JS, Peters L, Malone DC. Is real-world evidence used in P&T monographs and therapeutic class reviews? J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;23(6);613-20. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2017.16368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Real-world evidence. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/science-research/science-and-research-special-topics/real-world-evidence. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 15.AMCP Partnership Forum: advancing value-based contracting. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(11):1096-102. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2017.17342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duhig AM, Saha S, Smith S, Kaufman S, Hughes J. The current status of outcomes-based contracting for manufacturers and payers: an AMCP membership survey. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(5):410-15. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2017.16326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goble JA, Ung B, Van Boemmel-Wegmann S, Navarro RP, Parece A. Performance-based risk-sharing arrangements: U.S. payer experience. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(10):1042-52. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.10.1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.21st Century Cures Act. HR 34, 114th Cong. (2015). Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/34. Accessed February 1, 2020.

- 19.Langan SM, Schmidt SA, Wing K, et al. The reporting of studies conducted using observational routinely collected health data statement for pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE). BMJ. 2018;363:k3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown JD, Shewale AR, Talbert JC. Adherence to rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban for stroke prevention for newly diagnosed and treatment-naive atrial fibrillation patients: an update using 2013-2014 data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(9):958-67. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.9.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gatwood JD, Chisholm-Burns M, Davis R, et al. Disparities in initial oral antidiabetic medication adherence among veterans with incident diabetes. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(4):379-89. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oehrlein EM, Graff JS, Perfetto EM, Mullins CD. Peer-reviewed journal editors’ views on real-world evidence. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018;34 (1):111-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]