Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Although systemic sclerosis (SSc) with interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) is a serious condition and incurs a substantial clinical burden, the epidemiology has not been well characterized.

OBJECTIVE:

To estimate the incidence and prevalence of SSc and SSc-ILD among commercially insured adults in the United States.

METHODS:

Adults with medical claims between 2011 and 2016 for SSc or SSc-ILD with and without high-resolution computed tomography scans were identified from the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart. Incidence and prevalence were calculated as rates per 100,000 person-years and 100,000 people, respectively. The crude and age- and sex-adjusted prevalence and incidence of SSc and SSc-ILD were estimated and stratified by year and geography. Sensitivity analyses were conducted based on different cohort identification algorithms.

RESULTS:

Overall, the crude incidence rates of SSc and SSc-ILD were 16.4 and 1.2 per 100,000 person-years, respectively, and the crude prevalence was 24.4 and 6.9 per 100,000 people, respectively. Patient characteristics were generally similar between the SSc and SSc-ILD groups. Mean age range was 59.2-59.9 years and 61.8-62.9 years in the SSc and SSc-ILD groups, respectively. SSc had an age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate of 15.1 per 100,000 person-years and an adjusted prevalence of 25.9 per 100,000 people. The adjusted incidence rate of SSc-ILD was 1.1 per 100,000 person-years and the adjusted prevalence was 7.3 per 100,000 people.

CONCLUSIONS:

This study provides current estimates of the national incidence and prevalence of SSc and SSc-ILD, which have not been previously well characterized. Further research in the future may help to support health management strategies and resource allocation for adults with SSc and SSc-ILD in the United States.

What is already known about this subject

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a complex autoimmune connective tissue disease that causes a substantial economic burden.

More than 40% of patients with SSc show evidence of interstitial lung disease (ILD).

The epidemiology of SSc and SSc with ILD (SSc-ILD) in the United States varies based on different methodologies used.

What this study adds

This study is the most recent and robust assessment of the incidence and prevalence of SSc and SSc-ILD in a population of U.S. adults.

The incidence and prevalence estimates of SSc in the United States were 15.1 per 100,000 person-years and 25.9 per 100,000 people, respectively.

The incidence and prevalence of SSc-ILD were estimated to be 1.1 per 100,000 person-years and 7.3 per 100,000 people, respectively.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a complex autoimmune connective tissue disease characterized by vasculopathy or blood vessel damage, immunologic abnormalities, and extensive fibrosis of the skin and internal organs.1,2 SSc may be triggered by environmental events in genetically susceptible individuals.3 SSc affects the lungs, heart, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, and musculoskeletal system and has a substantial impact on morbidity, mortality, and quality of life.4-6 Although a rare disease, SSc poses a substantial economic burden on the health care system and society.4,7,8

In the United States, the average annual medical cost of patients with SSc, driven by ambulatory services, inpatient services, and medications, is more than 3 times greater than in those without SSc ($17,365 vs. $5,508; P < 0.001).9 Evidence of interstitial lung disease (ILD) has been observed in more than 90% of patients with SSc (SSc-ILD) on autopsy and in 40%-75% of patients with SSc based on lung function changes.10,11 Risk factors associated with the development and progression of ILD in patients with SSc include older age at disease onset, presence of diffuse cutaneous SSc, presence of anti-Scl-70/anti-topoisomerase I antibodies and/or absence of anticentromere antibodies, and African American ethnicity.12-14 ILD is characterized by chronic inflammation and fibrosis that progress to respiratory failure and death.15,16

Despite the seriousness and substantial clinical burden of SSc-ILD, the economic burden has not been well characterized except for a recent publication, reporting significantly higher health care resource utilization, direct and indirect costs, and work loss among patients with SSc-ILD compared with those without SSc-ILD.17 Clinical heterogeneity and multiple organ manifestations of SSc make diagnosis and management particularly challenging, and the epidemiology remains difficult to establish.5,18,19 Worldwide estimates of the incidence and prevalence of SSc vary by region,20-26 with higher rates observed in the United States, Europe, Australia, and Argentina and lower rates in Scandinavia, Japan, the United Kingdom, Taiwan, and India.23 Notable variations within the United States have been reported using different methodologies.24-26 Furthermore, most of these estimates were made before the current diagnostic guidelines were established.27 The epidemiologic challenges in SSc are also present in SSc-ILD, for which the incidence and prevalence remain largely unknown.

Understanding the occurrence and patient distribution of SSc and SSc-ILD in the United States is important for appropriately allocating and managing clinical- and population-level resources to counteract these debilitating conditions. The objective of this study was to estimate the crude and adjusted incidence and prevalence rates of SSc and SSc-ILD in the United States and to stratify the estimates by year and geography.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN

This retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart (Eden Prairie, MN), which includes administrative claims (medical/pharmacy claims and linked demographic information) for more than 180 million commercially insured individuals in the United States.28 All data were aggregated and deidentified to maintain confidentiality. This retrospective study was exempt from institutional review board approval because the claims data used did not contain any identifiable patient information and prospective data collection was not planned or implemented. Diagnoses of SSc and SSc-ILD were based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnostic codes (Supplementary Table 1, available in online article).

BASE CASE DEFINITIONS OF SSC AND SSC-ILD

Prevalent cases were identified between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2016. Incident cases were identified during the same period with a 1-year look-back period to January 1, 2010, to rule out any previous diagnosis. In the base case analysis, prevalent SSc cases were defined by the presence of ≥ 2 medical claims for SSc on different dates within a 1-year period between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2016. The date of first SSc diagnosis was defined as the index date. Incident SSc cases were required to have 1 year of continuous health insurance plan enrollment before the index date and ≥ 1 claim for SSc with no previous SSc diagnosis. Prevalent SSc-ILD cases were required to have ≥ 2 medical claims for SSc on different dates within 1 year and ≥ 2 medical claims for ILD on different dates within the entire study period. The later date of the first SSc or the first ILD claim was used as the index date. Incident SSc-ILD cases had ≥ 1 medical claim for SSc diagnosis, ≥ 1 medical claim for ILD diagnosis on different dates within a 1-year period, and ≥ 1 computed tomography (CT; Current Procedural Terminology, 4th edition [CPT-4] codes: 71250, 71260, 71275; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System [HCPCS] codes: S8032, S8092) or high-resolution CT (HRCT; CPT-4 code: 71270) scan within 180 days of the first ILD diagnosis). Incident SSc-ILD cases were also required to have 1 year of continuous health insurance plan enrollment before the first SSc or ILD diagnosis (whichever came first) and no previous SSc or ILD diagnosis during that period.

OUTCOMES AND ASSESSMENTS

Demographic characteristics including age, sex, insurance type, and geographic location or region were reported. Crude and age- and sex-adjusted prevalence and incidence of SSc and SSc-ILD for each calendar year and for the primary study period (2011-2016) were calculated.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics. Median and range and mean and standard deviation were reported for continuous variables, and frequency and percentage were reported for categorical variables. Incidence and prevalence were calculated as rates per 100,000 person-years and 100,000 people, respectively. The rates were adjusted by age and sex using weights based on the 2014 U.S. Census Bureau survey with 95% CIs reported for each adjusted rate.29 The adjusted rate radj = Σiwiri, where wi is the adjusted weight based on U.S. population for the ith age and sex stratum, and ri is the stratified crude rate.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess differences in the prevalence and incidence with different SSc and SSc-ILD case definitions, including (a) SSc prevalent cases defined by ≥ 1 medical claim (vs. base: ≥ 2 medical claims); (b) SSc-ILD prevalent cases defined by ≥ 1 medical claim for SSc plus ≥ 1 medical claim for ILD without HRCT/CT scan requirement (vs. base: ≥ 2 medical claims for SSc plus ≥ 2 medical claims for ILD); (c) SSc incident cases defined by ≥ 2 medical claims (vs. base: ≥ 1 medical claim); (d) SSc-ILD incident cases defined by ≥ 1 medical claim for SSc plus ≥ 1 medical claim for ILD plus ≥ 1 HRCT/CT scan within 365 days of the first ILD diagnosis (vs. base: 180 days); and (e) SSc-ILD incident cases defined by ≥ 1 medical claim for SSc plus ≥1 medical claim for ILD without HRCT/CT scan requirement (vs. base: with HRCT/CT scan requirement within 180 days of the first ILD diagnosis).

Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio version 1.1.383 (RStudio, PBC, Boston, MA) based on R version 3.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

PATIENT DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

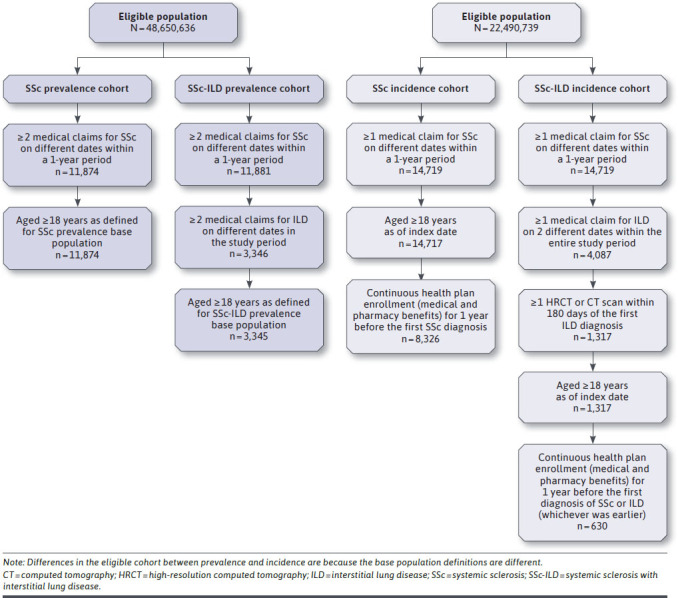

The database contained approximately 48 million health plan enrollees eligible to be considered for the SSc and SSc-ILD prevalence cohorts and nearly 22 million eligible for the SSc and SSc-ILD incidence cohorts. Patient attrition for each cohort is provided in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Patient Attrition

The demographic characteristics of included patients are summarized in Table 1. For patients with SSc, the mean age range was 59.2-59.9 years, with 40.4%-40.9% older than age 65 years. Most patients were women (80.5%-85.6%) and lived in the South (41.3%-41.5%), and approximately half (44.5%-50.2%) were covered by Medicare. Similarly, for patients with SSc-ILD, the mean age range was 61.8-62.9 years, with 45.3%-49.8% older than age 65 years. Most patients were women (78.7%-82.0%) and lived in the South (37.1%-41.1%), and approximately half (52.5%-56.3%) were covered by Medicare.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics, n (%) | SSc | SSc-ILD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence Cohort n = 8,326 | Prevalence Cohort n = 11,874 | Incidence Cohort n = 630 | Prevalence Cohort n = 3,345 | |

| Age, years | ||||

| 18-34 | 603 (7.2) | 557 (4.7) | 21 (3.3) | 97 (2.9) |

| 35-44 | 887 (10.7) | 1,048 (8.8) | 44 (7.0) | 239 (7.1) |

| 45-54 | 1,512 (18.2) | 2,226 (18.7) | 100 (15.9) | 579 (17.3) |

| 55-64 | 1,962 (23.6) | 3,181 (26.8) | 151 (24.0) | 914 (27.3) |

| ≥ 65 | 3,362 (40.4) | 4,862 (40.9) | 314 (49.8) | 1,516 (45.3) |

| Range | 18-89 | 18-89 | 18-89 | 19-89 |

| Mean (SD) | 59.2 (15.3) | 59.9 (13.6) | 62.9 (13.8) | 61.8 (12.9) |

| Median | 60 | 61 | 64 | 63 |

| Female | 6,699 (80.5) | 10,162 (85.6) | 496 (78.7) | 2,743 (82.0) |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1,059 (12.7) | 1,476 (12.4) | 83 (13.2) | 398 (11.9) |

| Midwest | 1,689 (20.3) | 2,627 (22.1) | 154 (24.4) | 751 (22.5) |

| South | 3,439 (41.3) | 4,930 (41.5) | 234 (37.1) | 1,375 (41.1) |

| West | 2,082 (25.0) | 2,749 (23.2) | 154 (24.4) | 799 (23.9) |

| Other | 57 (0.7) | 92 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) | 22 (0.7) |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Commercial | 4,618 (55.5) | 5,918 (49.8) | 299 (47.5) | 1,462 (43.7) |

| Medicare | 3,708 (44.5) | 5,956 (50.2) | 331 (52.5) | 1,883 (56.3) |

SSc = systemic sclerosis; SSc-ILD = systemic sclerosis with interstitial lung disease.

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE ESTIMATES

Overall, 8,326 incident cases of SSc were identified, with crude and adjusted overall incidence rates of 16.4 and 15.1 (95% CI = 14.8-15.5) per 100,000 person-years, respectively (Table 2). A total of 11,874 prevalent SSc cases were identified between 2011 and 2016, with crude and adjusted overall prevalence estimates of 24.4 and 25.9 (95% CI = 25.5-26.4) per 100,000 people, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Annual Incidence and Prevalence (95% CI) of SSc and SSc-ILD

| SSc (per 100,000 Person-Years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Rate | Age and Sex (Adjusted Rate) | 95% CI (Adjusted Rate) | |

| Annual incidence | |||

| 2011 | 21.5 | 19.9 | 19.0-20.9 |

| 2012 | 17.3 | 15.9 | 15.1-16.8 |

| 2013 | 16.4 | 14.9 | 14.1-15.7 |

| 2014 | 14.8 | 13.6 | 12.8-14.4 |

| 2015 | 14.7 | 13.1 | 12.3-13.8 |

| 2016 | 14.4 | 12.6 | 11.9-13.3 |

| Overall incidence | 16.4 | 15.1 | 14.8-15.5 |

| Annual prevalence | |||

| 2011 | 7.3 | 7.8 | 7.5-8.0 |

| 2012 | 10.7 | 11.2 | 10.9-11.5 |

| 2013 | 13.7 | 14.2 | 13.9-14.5 |

| 2014 | 16.8 | 17.1 | 16.8-17.5 |

| 2015 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 19.9-20.7 |

| 2016 | 24.6 | 24.3 | 23.8-24.7 |

| Overall prevalence | 24.4 | 25.9 | 25.5-26.4 |

| SSc-ILD (per 100,000 Person-Years) | |||

| Annual incidence | |||

| 2011 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| 2012 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.3 |

| 2013 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 |

| 2014 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.9-1.4 |

| 2015 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 |

| 2016 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 |

| Overall incidence | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.2 |

| Annual prevalence | |||

| 2011 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.0-2.3 |

| 2012 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0-3.3 |

| 2013 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.7-4.1 |

| 2014 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.6-5.0 |

| 2015 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.5-6.0 |

| 2016 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.6-7.0 |

| Overall prevalence | 6.9 | 7.3 | 7.1-7.6 |

SSc = systemic sclerosis; SSc-ILD = systemic sclerosis with interstitial lung disease.

In total, 630 incident SSc-ILD cases were identified, with crude and adjusted incidence rates of 1.2 and 1.1 (95% CI = 1.0-1.2) per 100,000 person-years, respectively (Table 2). Further, 3,345 prevalent cases of SSc-ILD were identified between 2011 and 2016, with crude and adjusted prevalence estimates of 6.9 and 7.3 (95% CI = 7.1-7.6) per 100,000 people, respectively.

The adjusted annual incidence of SSc appeared to have decreased slightly over the study period, whereas the adjusted annual incidence of SSc-ILD remained relatively stable (Figure 2). The change from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM in 2015 should be considered when interpreting the results. State-level incidence and prevalence of SSc and SSc-ILD during the study period are presented in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2 (available in online article), respectively. Notably, in Vermont, Hawaii, Rhode Island, the Dakotas, Connecticut, Wyoming, Maine, and New Mexico, the incidence and prevalence estimates were high, but in Alaska and Puerto Rico, the corresponding number was zero (Supplementary Table 2, available in online article). Similar patterns were observed for both SSc and SSc-ILD.

FIGURE 2.

Age- and Sex-Adjusted Annual Incidence (95% CI) of SSc and SSc-ILD

Sensitivity analyses of different case definitions showed expectedly higher estimates when only 1 diagnosis code was required. The SSc-ILD case definition was most sensitive to the exclusion of an HRCT or CT scan requirement (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity Analysis Results from Case Definition Scenarios

| SSc Case Definitions | Base Case | Sensitivity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude incidence (per 100,000 person-years) | (≥ 1 medical claim in 1 year) 16.4 | (≥ 2 medical claims in 1 year) 7.5 | |

| Crude prevalence (per 100,000 individuals) | (≥ 2 medical claims in 1 year) 24.4 | (≥ 1 medical claim in 1 year) 44.1 | |

| SSc-ILD Case Definitions | Base Case | Sensitivity 1 (≥ 1 Medical Claim of SSc and ILD and ≥ 1 HRCT or CT Within 365 Days of ILD) | Sensitivity 2 (≥ 1 Medical Claim of SSc and ILD, no HRCT or CT) |

| Crude incidence (per 100,000 person-years) | (≥ 1 medical claim of SSc and ILD and ≥1 HRCT or CT within 180 days of ILD) 1.2 | 1.4 | 3.6 |

| Crude prevalence (per 100,000 people) | (≥ 2 medical claims of SSc and ILD) 6.9 | – | 9.2 |

CT = computed tomography; HRCT = high-resolution CT; ILD = interstitial lung disease; SSc = systemic sclerosis; SSc-ILD = systemic sclerosis with interstitial lung disease.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study reports the incidence and prevalence of SSc and SSc-ILD among insured U.S. adults over a 6-year analysis period. The overall age- and sex-adjusted incidence and prevalence estimates of SSc in the United States were 15.1 per 100,000 person-years and 25.9 per 100,000 people, respectively. The overall adjusted incidence and prevalence of SSc-ILD were estimated to be 1.1 per 100,000 person-years and 7.3 per 100,000 people, respectively. Given the lack of validated disease cohort definitions based on claims data sources, we examined several case definitions to identify patients with SSc or SSc-ILD. In clinical practice, not all patients with SSc-ILD may receive a comprehensive clinical assessment that includes an HRCT scan of the chest regularly, so we applied a case definition of SSc-ILD excluding the requirement of HRCT. The range of estimates provided by these sensitivity analyses will be useful to assess the epidemiology of SSc and SSc-ILD in different clinical practice scenarios.

The present study provides recent estimates for the epidemiology of SSc that are in the range of estimates generated by past studies.24,30,31 The reported incidence of SSc in other studies ranged from 1.4 to 19.3 per 100,000 person-years across different U.S. regions, with the variation likely attributable to the use of different data sources and methodologies.24,30-32 Similarly, the reported prevalence of SSc in other studies ranged from 13.5 to 242.0 per 100,000 people in the United States.24-26,30,31,33 An analysis of administrative claims between 2003 and 2008 reported an age- and sex-adjusted SSc incidence of 5.6 per 100,000 person-years, much lower than the 15.1 identified here.24 The study defined cases of SSc as insured adults with ≥ 1 inpatient medical claim or ≥ 2 outpatient or emergency room medical claims at least 30 days apart, whereas no minimum gap between 2 medical claims of SSc was required in our study. The data source was much smaller (approximately 35 vs. 180 million covered lives) and may have had different population coverage, and estimates were adjusted against the 2000 U.S. census.

An analysis of the Olmsted County (Minnesota) medical records database between 1980 and 2010 reported a range of SSc incidence rates from 1.4 (narrow criteria) to 2.4 (broad criteria) per 100,000 person-years.30 These “narrow” and “broad” case definitions from manually extracted medical records were based on the 1980 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria and another set of clinical criteria published in 1988, which were reviewed and adjudicated by a single rheumatologist.30 It appears to be a more stringent algorithm. The data sources, sample sizes, and case definitions were very different from those used in our study. The Olmsted County study also reported an SSc point prevalence estimate of 39.9 per 100,000 people on December 31, 2010,30 which was similar to the crude prevalence estimate of 27.7 per 100,000 people reported for Minnesota in our study.

A recent systematic review, including the studies discussed above, reported annual incidence and prevalence estimates of SSc in the United States ranging from 1.4 to 5.6 and 13.5 to 44.3 per 100,000 individuals, respectively.31 The review also reported the high variability in the incidence and prevalence of SSc-ILD. Given the lack of consensus on how SSc-ILD should be diagnosed, the variability could be attributed to the difference in methods for diagnosing ILD such as pulmonary function tests and HRCT.31

Differences in the methodologies (case definitions and statistical adjustments) and data sources (geographic region and study period) are likely responsible for the variability in epidemiological estimates over the years.23-26,32-34 The prevailing age range and sex of patients with SSc and SSc-ILD have not varied widely, as patients aged older than 45 years and women have been consistently prominent in the populations.24,26,30,32,34 Consistent with the results of this study, results of previous studies have shown that more than 80% of patients with SSc are women and are aged 45 years or older.24,26,30

The prevalence of other autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) also varies due to small study populations, differences in case definitions, and study methods.35 Estimates from the California Lupus Surveillance Project showed that the age-standardized annual incidence and prevalence of SLE were 4.6 per 100,000 person-years and 84.8 per 100,000 people, respectively, for 2007-2009.36 Women had a higher incidence than men (8.6 versus 0.7 per 100,000 person-years). Results from the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program showed that the age-standardized incidence and prevalence of SLE were 4.6 per 100,000 person-years and 62.2 per 100,000 people, respectively, for 2007-2009. Similarly, women had an almost 8 times higher incidence than men (7.9 versus 1.0 per 100,000 person-years).37 Results of a retrospective cohort analysis of U.S.-based administrative claims databases showed that the incidence and prevalence of ILD associated with rheumatoid arthritis—another autoimmune disease—ranged from 2.7 to 3.8 cases per 100,000 people and 3.2 to 6.0 cases per 100,000 people, respectively, from 2004 to 2013.38 Furthermore, most patients with rheumatoid arthritis-related ILD were women.38

When interpreting the results, the strengths and potential limitations of this study should be considered. This is one of the largest and most recent studies on the incidence and prevalence of SSc and the first for SSc-ILD in the United States. Our results provide insights into the epidemiology of SSc and SSc-ILD chronologically and by state-level geography across the United States. Considering the lack of clinical information and validated case definitions in administrative claims data, we applied several case definition scenarios to identify patients with SSc or SSc-ILD. Research exploring our observed sensitivity of estimates to imaging procedure criteria may help solidify more consistent approaches in the future.

LIMITATIONS

Our findings may not be generalizable to populations outside the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart administrative claims database. Case definition variables were limited to those available in the data sources used for this study as we did not have access to the medical records. Not all demographic information is captured in claims data, such as race or ethnicity. Administrative claims may also have missing or misclassified data due to variability in medical coding practices. Moreover, a diagnosis code may be a marker for a rule-out criterion instead of the actual disease.24 Conversion from ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM may have mapping issue and cause sample loss in patient identification. Incident cases may not have been true newly diagnosed cases because not all members had complete medical histories available, and the assessment of previous diagnoses was limited to 1 year before the index date. All of the disease identification definitions used to identify the SSc and SSc-ILD populations had not been validated; however, multiple scenario analyses were conducted to examine the impact of different criteria on the estimation.

Conclusions

This study is the most recent and, to our knowledge, the most robust assessment of the incidence and prevalence of both SSc and SSc-ILD of U.S. adults. Future research may help investigate the approach and findings of our study, with the aim of supporting better health management strategies and resource allocation for patients with SSc and SSc-ILD in the United States. Additional work on refining the algorithm should be conducted, which could potentially lead to differences in estimates provided in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing, editorial support, and formatting assistance was provided by Suchita Nath-Sain, PhD, and Jeff Frimpter, MPH, of Cactus Life Sciences (part of Cactus Communications), which was contracted and compensated by BIPI for these services.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barsotti S, Orlandi M, Codullo V, et al. One year in review 2019: systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2019;37 Suppl 119(4):3-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denton CP. Advances in pathogenesis and treatment of systemic sclerosis. Clin Med (Lond). 2015;15(Suppl 6):s58-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cottin V, Brown KK. Interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD). Respir Res. 2019;20(1):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fischer A, Zimovetz E, Ling C, Esser D, Schoof N. Humanistic and cost burden of systemic sclerosis: a review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(11):1147-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, et al. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(8):1327-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elhai M, Meune C, Boubaya M, et al. Mapping and predicting mortality from systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(11):1897-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chevreul K, Brigham KB, Gandré C, Mouthon L. The economic burden and health-related quality of life associated with systemic sclerosis in France. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44(3):238-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López-Bastida J, Linertová R, Oliva-Moreno J, et al. Social/economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with scleroderma in Europe. Eur J Health Econ Suppl. 2016;17(Suppl 1):109-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furst DE, Fernandes AW, Iorga SR, Greth W, Bancroft T. Annual medical costs and healthcare resource use in patients with systemic sclerosis in an insured population. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(12):2303-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varga J. Systemic sclerosis: an update. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66(3):198-202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bussone G, Mouthon L. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10(5):248-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaeger VK, Wirz EG, Allanore Y, et al. Incidences and risk factors of organ manifestations in the early course of systemic sclerosis: a longitudinal EUSTAR study. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0163894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nihtyanova SI, Schreiber BE, Ong VH, et al. Prediction of pulmonary complications and long-term survival in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(6):1625-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steen V, Domsic RT, Lucas M, Fertig N, Medsger TA Jr. A clinical and serologic comparison of African American and Caucasian patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(9):2986-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalchiem-Dekel O, Galvin JR, Burke AP, Atamas SP, Todd NW. Interstitial lung disease and pulmonary fibrosis: a practical approach for general medicine physicians with focus on the medical history. J Clin Med. 2018;7(12):476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells AU, Margaritopoulos GA, Antoniou KM, Denton C. Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(2):213-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Z, Fan Y, Thomason D, et al. Economic burden of illness among commercially insured patients with systemic sclerosis with interstitial lung disease in the USA: a claims data analysis. Adv Ther. 2019;36:1100-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann-Vold AM, Gunnarsson R, Garen T, Midtvedt Ø, Molberg Ø.. Performance of the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis (SSc) in large, well-defined cohorts of SSc and mixed connective tissue disease. J Rheumatol. 2015;42(1):60-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nihtyanova SI, Ong VH, Denton CP.. Current management strategies forsystemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(2 Suppl 81):156-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alamanos Y, Tsifetaki N, Voulgari PV, et al. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis in northwest Greece 1981 to 2002. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34(5):714-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allcock RJ, Forrest I, Corris PA, Crook PR, Griffiths ID. A. study of the prevalence of systemic sclerosis in northeast England. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43(5):596-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arias-Nuñez MC, Llorca J, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, et al. Systemic sclerosis in northwestern Spain: a 19-year epidemiologic study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87(5):272-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes J, Mayes MD. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis: incidence, prevalence, survival, risk factors, malignancy, and environmental triggers. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(2):165-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furst DE, Fernandes AW, Iorga SR, Greth W, Bancroft T. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis in a large U.S. managed care population. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(4):784-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayes MD. Scleroderma epidemiology. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2003;29(2):239-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson D Jr, Eisenberg D, Nietert PJ, et al. Systemic sclerosis prevalence and comorbidities in the U.S., 02001-2002. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(4):1157-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(11):2737-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Optum. Explore our real-world data. 2020. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.optum.com/solutions/life-sciences/explore-data.html

- 29.United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey: 2010-2014 ACS 5-year data profile. 2020. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.census.gov/acs/www/data/data-tables-and-tools/data-profiles/2014/

- 30.Bauer PR, Schiavo DN, Osborn TG, et al. Influence of interstitial lung disease on outcome in systemic sclerosis: a population-based historical cohort study. Chest. 2013;144(2):571-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergamasco A, Hartmann N, Wallace L, Verpillat P. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:257-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayes MD, Lacey JV Jr, Beebe-Dimmer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in a large U.S. population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(8):2246-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maricq HR, Weinrich MC, Keil JE, et al. Prevalence of scleroderma spectrum disorders in the general population of South Carolina. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32(8): 998-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steen VD, Oddis CV, Conte CG, Janoski J, Casterline GZ, Medsger TA Jr. Incidence of systemic sclerosis in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania. A twenty-year study of hospital-diagnosed cases, 1963-1982. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(3):441-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Reviewed October 17, 2018. Accessed September 6, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/lupus/facts/detailed.html

- 36.Dall’Era M, Cisternas MG, Snipes K, Herrinton LJ, Gordon C, Helmick CG. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in San Francisco County, California: the California Lupus Surveillance Project. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(10):1996-2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Izmirly PM, Wan I, Sahl S, et al. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus in New York County (Manhattan), New York: the Manhattan Lupus Surveillance Program. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(10):2006-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raimundo K, Solomon JJ, Olson AL, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease in the United States: prevalence, incidence, and healthcare costs and mortality. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(4):360-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]