Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Medication therapy management (MTM) was officially recognized by the federal government in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, which requires Medicare Part D plans that offer prescription drug coverage to establish MTM programs (MTMPs) for eligible beneficiaries. Even though the term “MTM” was first used in 2003, pharmacists have provided similar services since the term “pharmaceutical care” was introduced in 1990. Fairview Health Services, a large integrated health care system, implemented a standardized pharmaceutical care service system in 1998, naming it a pharmaceutical care-based MTM practice in 2006.

OBJECTIVE:

To present the clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes of 10 years of delivering MTM services to patients in a health care delivery system.

METHODS:

Data from MTM services provided to 9,068 patients and documented in electronic therapeutic records were retrospectively analyzed over the 10-year period from September 1998 to September 2008 in 1 health system with 48 primary care clinics. Patients eligible for MTM services were aged 21 years or older and either paid for MTM out of pocket or met their health care payer’s criteria for MTM reimbursement; the criteria varied for Medicaid, Medicare, and commercially insured enrollees. All MTM was delivered face to face. Health data extracted from the electronic therapeutic record by the present study’s investigators included patient demographics, medication list, medical conditions, drug therapy problems identified and addressed, change in clinical status, and pharmacist-estimated cost savings. The clinical status assessment was a comparison of the first and most recent MTM visit to measure whether the patient achieved the goals of therapy for each medical condition (e.g., the blood pressure of a patient with diabetes and hypertension will be less than 130/80 millimeters mercury [mmHg] in 1 month; the patient with allergic rhinitis will be relieved of his complaints of nasal congestion, runny nose, and eye itching within 5 days). Goals were set according to evidence-based literature and patient-specific targets determined cooperatively by pharmacists, patients, and physicians. Cost-savings calculations represented MTM pharmacists’ estimates of medical services (e.g., office visits, laboratory services, urgent care visits, emergency room visits) and lost work time avoided by the intervention. All short-term (3-month) estimated health care savings that resulted from addressing drug therapy problems were analyzed. The expenses of these avoided services were calculated using the health system’s contracted rates for services provided in the last quarter of 2008. The return on investment (ROI) was calculated by dividing the pharmacist-estimated savings by the cost of MTM services in 2008 (number of MTM encounters times the average cost of an MTM visit). The humanistic impact of MTM services was assessed using the results from the second patient satisfaction survey administered in 2008 (new patients seen from January through December 2008) for the health system’s MTM program.

RESULTS:

A total of 9,068 patient records were in the documentation system as of September 30, 2008. During the 10-year period, there were 33,706 documented encounters (mean 3.7 encounters per patient). Of 38,631 drug therapy problems identified and addressed by MTM pharmacists, the most frequent were a need for additional drug therapy (n = 10,870, 28.1%) and subtherapeutic dosage (n = 10,100, 26.1%). In the clinical status assessment of the 12,851 medical conditions in 4,849 patients who were not at goal when they enrolled in the program, 7,068 conditions (55.0%) improved, 2,956 (23.0%) were unchanged, and 2,827 (22.0%) worsened during the course of MTM services. Pharmacist-estimated cost savings to the health system over the 10-year period were $2,913,850 ($86 per encounter) and the total cost of MTM was $2,258,302 ($67 per encounter), for an estimated ROI of $1.29 per $1 in MTM administrative costs. In the patient satisfaction survey, 95.3% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their overall health and well-being had improved because of MTM.

CONCLUSION: Pharmacist estimates of the impact of an MTM program in a large integrated health care system suggest that the program was associated with improved clinical outcomes and cost savings. Patient satisfaction with the program was high.

What is already known about this subject

The pharmacy profession has been moving from a product-focused to a patient-focused practice. The recognition of medication therapy management (MTM) by the federal government in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 provides pharmacists with the opportunity to expand and to be reimbursed for direct patient care services.

Types of MTM programs vary from drug utilization reviews to comprehensive face-to-face pharmaceutical care services.

Studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of MTM programs in improving the control of several disease states such as hypertension. In one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of community pharmacy-based MTM in patients with diabetes and hypertension, the percentage of patients at goal blood pressure increased from 16.0% to 48.0% in patients who received MTM and decreased from 20.0% to 6.67% in the control group. In another RCT of physician/pharmacist collaboration in patients with hypertension, mean blood pressure decreased from baseline to 6-month follow-up by 6.8/4.5 millimeters mercury (mmHg) in the control group and by 20.7/9.7 mmHg in the group that received collaborative care.

What this study adds

In an MTM program implemented in a large integrated health care system, pharmacists found that 85% of patients had at least 1 drug therapy problem, and 29% of patients had 5 or more drug therapy problems.

The results suggest that the major drug therapy problem in this population is the underutilization of effective medications. Of 38,631 drug therapy problems identified and addressed by MTM pharmacists, the most frequent were a need for additional drug therapy (n=10,870, 28.1%) and subtherapeutic dosage (n=10,100, 26.1%).

Pharmacist-estimated cost savings to the health system over the 10-year period were $2,913,850 ($86 per encounter), and the total cost of MTM was $2,258,302 ($67 per encounter), for an estimated return on investment of $1.29 per $1 in MTM costs.

Medication therapy management (MTM) was officially recognized by the federal government in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 (MMA 2003).1 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), through the MMA 2003, requires each Medicare Part D plan to establish MTM programs (MTMPs) for eligible beneficiaries as part of their benefits. MTMPs must be designed to “optimize therapeutic outcomes through improved medication use” and “reduce the risk of adverse events, including adverse drug reactions.”2 Pharmacists were the only health care provider specifically mentioned as potential MTM providers; however, “other qualified providers” can also deliver these services.2 Additionally, the MMA 2003 did not include a specific list of services that should be provided to Medicare beneficiaries.3 The draft Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual released by CMS in December 2006 stated that “CMS believes that existing standards and performance measures are insufficient to support further specification for MTMP services and service level requirements, and therefore plans need the discretion to decide on which methods and which providers are best for providing MTMP services available under their specific MTMP.”4

Even though the term “MTM” was introduced with the MMA 2003, pharmacists have previously developed and implemented similar programs called “pharmaceutical care.”3 Whereas MTM in the MMA 2003 is specific to Part D enrollees, pharmaceutical care can be provided to anyone. Pharmaceutical care is a practice in which the pharmacist works directly with a patient and other health care providers using interventions designed to enhance the results obtained from medication therapies.5,6 MTM provided to Part D patients is a logical extension of the provision of pharmaceutical care services to diverse groups of patients, which has been performed by pharmacists for many years. Programs of this kind represent the pharmacy profession’s shift from a product-focused to patient-centered practice.7-14

Several studies have shown the effectiveness of pharmaceutical care in patients with diabetes,15,16 in patients with heart failure,17,18 and in high-risk Medicare beneficiaries.19 Other studies also demonstrate the positive effect of various pharmacist interventions on patients’ outcomes.20-22 Planas et al. (2009) found in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that a community pharmacy-based MTM program was effective in improving blood pressure control of managed care enrollees with diabetes and hypertension; the percentage of patients at blood pressure goal increased from 16.0% to 48.0% in patients who received MTM and decreased from 20.0% to 6.67% in the control group.15 In another RCT, Doucette et al. (2009) evaluated the effect of a diabetes care service provided by community pharmacists on primary clinical outcomes and on patients’ reported self-care activities.16 These authors found that compared with the control group, patients who received pharmacists’ interventions significantly increased the number of days per week that they engaged in a set of diet and diabetes self-care activities, although changes in hemoglobin A1c, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and blood pressure were not significantly different between the 2 study groups.

Welch et al. (2009) assessed the impact of an MTMP on mortality, health care utilization, and prescription medication costs. They found that Medicare Part D beneficiaries who opted into the MTMP were less likely to die compared with beneficiaries who opted out (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 0.5, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.3-0.9) but were more likely to be hospitalized (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.1-2.0) and to have increased medication costs (OR = 1.4, 95% CI = 1.1-1.9) during follow-up.19 Moreover, Carter el al. (2009) found in an RCT that patients treated with collaborative intervention between pharmacist and physician achieved significantly better mean blood pressure and overall blood pressure control rates compared with a control group, with mean blood pressure declining from baseline to 6-month follow-up by 20.7/9.7 millimeters mercury (mmHg) in the intervention group and by 6.8/4.5 mmHg in the control group.22 However, in another RCT, Nietert et al. (2009) found no significant differences between time to refill of prescriptions for common chronic conditions, comparing patients contacted by pharmacists via telephone or fax with patients in usual care.23

The pharmacy profession has developed and reached consensus on an MTM definition.24-29 Although this definition has not been officially recognized by CMS or most other nonpharmacy entities, in 2005 the American Medical Association established Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for reimbursement of MTM services provided by a pharmacist.29

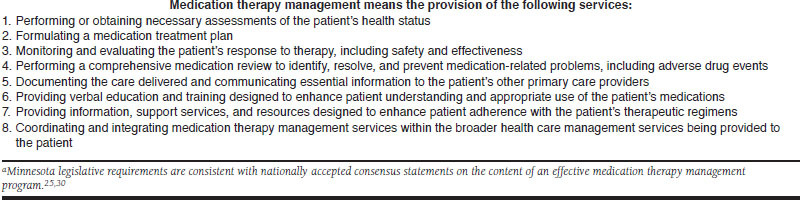

In 2005, the Minnesota state legislature authorized coverage of MTM services provided by pharmacists to medical assistance and general assistance medical care recipients.30 Medical assistance is the largest of Minnesota’s 3 publicly funded health care programs, providing coverage for low-income senior citizens, children and families, and people with disabilities. MTM is defined in Minnesota statute as the provision of pharmaceutical care services by a licensed pharmacist to “optimize the therapeutic outcomes of the patient’s medications.”30 Coverage of MTM services is provided for medical assistance recipients “taking four or more prescriptions to treat or prevent two or more chronic medical conditions, or when prior authorized by the commissioner for a recipient with a drug therapy problem that is identified and has resulted, or is likely to result, in significant nondrug program costs.”30 The Minnesota statute promulgated requirements for the types of services encompassed by MTM (Figure 1). This legislation also specified the requirements for pharmacists’ enrollment as providers and the space and privacy requirements for the consultation area where the patient receives MTM services. In 2007, the results of a nonpeer-reviewed report evaluating the effectiveness of the first year of the Minnesota MTM care program showed significant improvement in patients’ clinical outcomes but no significant differences in health care expenditures in a preliminary analysis.31 A significant body of evidence has been produced in Minnesota related to MTM from the time that pharmaceutical care theory was put into practice until more recently when investigations of MTM outcomes began.9,31-35

FIGURE 1.

Minnesota Legislative Requirements for Pharmacists’ Provision of Medication Therapy Management Services for Medical Assistance and General Assistance Medical Care Recipientsa

Description of the Fairview MTM Program

The MTM program assessed in the present study is a service of Fairview Pharmacy Services, which is a subsidiary of Fairview Health Services, a Minnesota nonprofit corporation and one of the largest health care provider organizations in the state. Fairview Health Services, in partnership with the University of Minnesota, is a network of 7 hospitals, 48 primary care clinics, 55 specialty clinics, and 28 retail pharmacies that serves Minneapolis-St. Paul, as well as communities throughout greater Minnesota and the Upper Midwest. More than 2.7 million patients are seen in 1.1 million Fairview clinic visits annually. From 1997-1998, Fairview Pharmacy Services established pharmaceutical care practices, initially in Fairview retail pharmacies and then in primary care clinics, where pharmacists were not associated with dispensing activities and could more easily become part of the health care team. All MTM pharmacists within the system use the same standardized patient care process and are overseen by the MTM management team to promote consistency.

Fairview Pharmacy Services provides MTM to the following groups: (a) Medicaid beneficiaries taking 4 or more prescriptions to treat or prevent 2 or more chronic medical conditions; (b) patients enrolled with contracted Medicare Part D plan sponsors; (c) beneficiaries of contracted self-funded employers; (d) all Fairview employees regardless of the number of diseases or medications; and (e) private-pay patients. The eligibility criteria for MTM services vary among Medicare Part D plan sponsors and contracted employers. Some employers target participants based on the number of chronic medications used, whereas others target specific disease states.

The MTM program enrollment process is “opt-in.” Eligible patients are recruited directly by the program using mailed letters. In order to participate, patients must complete and return an enrollment form. The patient is then contacted to set up an appointment with the MTM pharmacist. To stay enrolled in the program, the patient must come to all appointments with the pharmacist, as agreed upon by the patient and the pharmacist at the first visit. Sponsors pay per visit to the pharmacist for patients enrolled in the program. The cost of the MTM visit depends upon the complexity of each patient’s case as determined by the patient’s number of current medications, number of medical conditions, and number of drug therapy problems identified by the pharmacist.

MTM is provided to patients through face-to-face consultations. Initial appointments are scheduled for 60 minutes, and follow-up visits are scheduled for 30 minutes. MTM is provided in a private space, usually a consultation/exam room at a clinic. As required by Minnesota law, the space is private and entirely devoted to patient care.

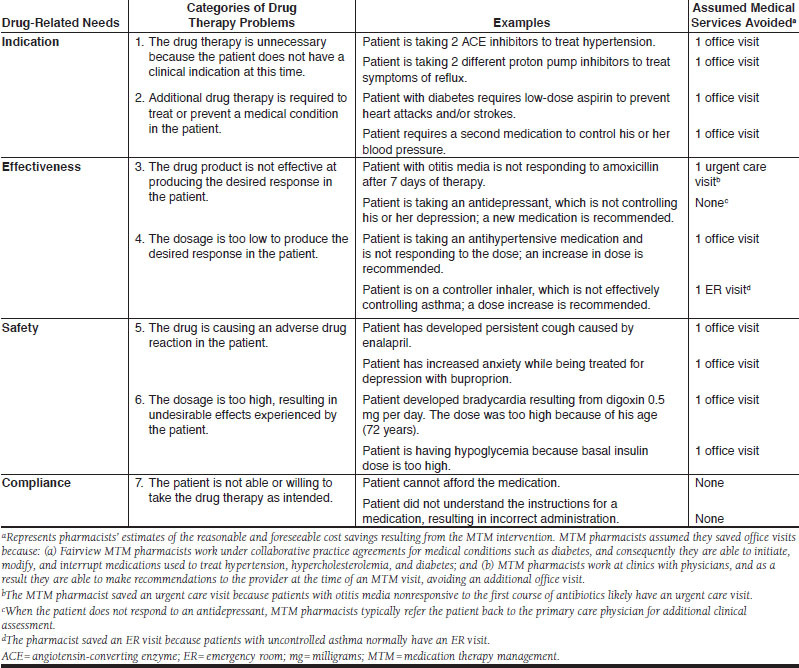

MTM pharmacists follow the philosophy and the patient care process of pharmaceutical care.6,7,14 Each MTM encounter follows a systematic review process designed to identify and resolve drug therapy problems and promote optimal patient outcomes (Figure 2). MTM pharmacists’ responsibilities include the following: (a) focus on the “whole” patient (i.e., the pharmacist assesses all of the patient’s diseases and medications); (b) identification of a patient’s drug-related needs; (c) promotion of appropriate indications, safety, and compliance for all drug therapies by identification, resolution, and prevention of drug-related problems; (d) achievement and documentation of therapy outcomes; and (e) collaboration with all members of a patient’s care team.

FIGURE 2.

Description of Drug Therapy Problem Categories and Assumed Medical Services Avoided

MTM pharmacists document therapeutic outcomes at every patient encounter using a pharmaceutical care software documentation program. Therapeutic goals are established for each of a patient’s medical conditions during the initial stage of care plan development. The patient, prescriber, and pharmacist communicate to discuss patient expectations and goals of therapy. For some medical conditions, such as diabetes, there are collaborative practice agreements in place under which the MTM pharmacist can initiate, modify, or discontinue drug therapy as well as order laboratory tests related to diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia, according to the terms of the collaborative agreements.

Ten pharmacists (6.1 full-time equivalents [FTEs]) provide MTM services in 17 of the 48 clinics in the Fairview system. All MTM pharmacists have been certified in the practice of pharmaceutical care by the Peters Institute of Pharmaceutical Care at the University of Minnesota and credentialed by Fairview Pharmacy Services. A practice management team comprising a pharmacy director, a product manager, an operations manager, and a business specialist supports the MTM program. Moreover, MTM pharmacists are preceptors for pharmacy students during 10-week rotations in their last year of pharmacy school. The Fairview MTM program also offers a 1-year residency in pharmaceutical care. Practitioners and the management team of the MTM program are involved in education at the University of Minnesota, College of Pharmacy, by teaching pharmacy students and graduate students how the principles of MTM are put into practice.

Quality assurance is a key component of the MTM program to promote consistency in the care provided to each patient. One important initiative is the biannual evaluation of practitioners’ documentation. A random sample of patients from all MTM practitioners is evaluated by the MTM operations manager for full documentation in accordance with the MTM program’s policies and procedures. Another quality improvement initiative is the monthly practitioners’ meeting, when MTM pharmacists present patients’ cases and discuss their practices.

The objective of the present study’s analysis was to describe the clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes of services provided by the MTM program since September 1998.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of the 9,068 patients seen in the Fairview MTM program from September 1, 1998, through September 30, 2008, was conducted. All patients who were aged 21 years or older and who either met their health care payer’s reimbursement criteria for MTM or paid for MTM out of pocket were included in the analysis. Data were abstracted from the MTM documentation system (Assurance System) that stored all the documented data from all patients enrolled in the MTM program during the 10-year period. Data abstracted by the first author of this article included the following fields: patients’ demographics, number of MTM consultations, number of medications taken, number and types of medical conditions, types of drug therapy problems identified and addressed, types of interventions implemented to resolve drug therapy problems, change in patients’ clinical status, and pharmacist-estimated health care savings.

The number of medications taken by patients included all active over-the-counter (OTC) medications, supplements, herbal products, medications used to treat acute conditions or used for a limited time period (e.g., antibiotics, analgesics), and medications prescribed for chronic conditions (e.g., antihypertensive medications, antidepressant agents). The presence of medical conditions was determined using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes documented first in the patient’s electronic medical record and then in the Assurance System by the MTM pharmacist.

Drug Therapy Problems

Drug therapy problems were classified into 4 major categories—indication, effectiveness, safety, and compliance—and 7 subcategories (Figure 2). The classification of drug therapy problems was carried out using a systematic process of problem solving referred to as Pharmacotherapy Workup.6,36 The workup algorithm asks if the medication is appropriate for that specific patient; if the medication is the most effective and the right dose to help the patient to achieve his or her clinical goals; if the medication is the safest for that patient; and if the patient is able and willing to adhere to the drug regimen. Nonadherence is defined in the pharmaceutical care practice model as the patient’s inability or unwillingness to take a drug regimen that the practitioner has clinically judged to be appropriately indicated, adequately efficacious, and able to produce the desired outcomes.6 In this decision-making process, before evaluating patients’ medication-taking behaviors (following or not following the instructions), practitioners attempt to certify that patients are taking all the medications and only the medications that they need and that all of the medications they are taking are effective and safe. The documentation of drug therapy problems also includes the medications involved, the medical conditions affected, the causes of the problem, and the interventions implemented to attempt resolution of the problem. For nonadherence, the MTM pharmacist documents the main reason the patient is nonadherent, which will determine the intervention used to address this drug therapy problem.

Clinical Status Assessment

For each patient, change in clinical status was evaluated and documented by the MTM pharmacist at each MTM consultation.6 A clinical outcome status was documented as “resolved,” “stable,” “improved,” or “partially improved” when the patient was considered to be achieving the goal of therapy for a specific medical condition, and the following terms were used when the patient was not achieving the goal of therapy: “unimproved,” “worsened,” or “failure.”

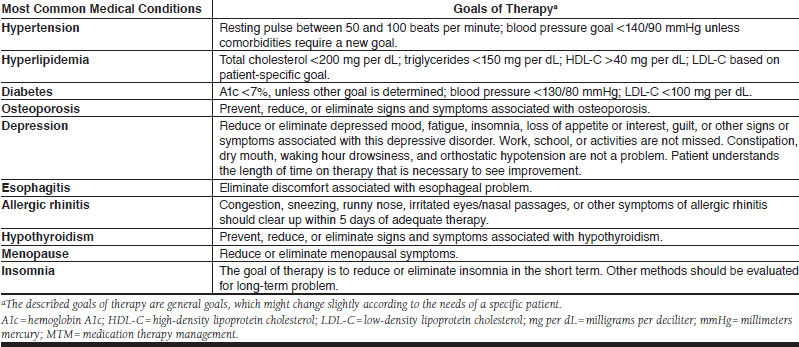

The pharmacist, patient, and physician cooperatively determined goals of therapy that served as the agreed-upon targets for care plan actions and interventions. For each drug therapy indication, goals included clinical parameters described in the literature and patient-specific goals. Drug therapy goals were intended to be measurable, observable, realistic, and achievable within a specified time frame (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Description of the Goals of Therapy for the Most Common Medical Conditions in the MTM Program

For the present study’s analysis, we evaluated the patients’ clinical status at the first and at the most recent MTM consultation. Specifically, for patients not at goal at the first MTM visit, the number of patients not at therapy goal (including clinical status unimproved, worsened, and failure) and the number with improved clinical status (resolved, stable, improved, or partially improved) in the last visit were documented. This approach was deemed reliable and valid based on the results of a quality assessment analysis conducted by Isetts et al. (2003), in which a 12-member panel of physicians and pharmacists reviewed clinical determinations made by Fairview MTM pharmacists from January 1999 through March 2002 for 300 randomly selected patient records.32 For each patient, 4 types of determinations were assessed, including identification of the drug therapy problem, actions taken to resolve the problem, assessment of clinical status including goal achievement, and estimate of costs avoided by the intervention. Panel members concurred with 94.2% of determinations, disagreed with 2.2%, and expressed neutrality on 3.6%. Intraclass correlation coefficients ranged from 0.73 to 0.85.32

To assess clinical status outcomes in more detail, a subset of data for employees of a self-funded employer was analyzed. This analysis focused on the clinical outcomes of 110 patients with diabetes who were followed by MTM pharmacists from August 2007 to December 2008. Even though the MTM pharmacist assesses all of a patient’s conditions and medications, for the purposes of this analysis only the clinical outcomes associated with diabetes care were described. Five measures (“the D5”) that assess optimal diabetes care, as it is suggested by the State of Minnesota, were used to determine the clinical outcomes of this group of patients.37 The D5 is a set of 5 treatment goals that when achieved together represent the gold standard for managing diabetes. Reaching all 5 goals greatly reduces a patient’s risk for the cardiovascular problems associated with diabetes. The D5 goals include the following: (a) A1c less than 7%; (b) blood pressure less than 130/80 mmHg; (c) LDL-C less than 100 milligrams per deciliter (mg per dL); (d) daily aspirin use (for patients aged 41 to 75 years), and (e) documented tobacco-free status. The percentage of MTM patients reaching all 5 goals in December 2008 was compared with the percentage of patients reaching all goals in the first MTM visits that occurred in August 2007.

Economic Outcomes

To estimate the economic impact of MTM, all health care savings documented by MTM pharmacists in the Assurance System were reviewed. MTM pharmacists projected the short-term (3-month) cost savings resulting from their interventions to resolve drug therapy problems (Figure 2). Direct savings included medical services avoided as a result of the intervention, including office visits, emergency room (ER) visits, urgent care visits, long-term care stays, and hospitalizations. Avoidance of lost work time was also estimated. Only those savings considered reasonable and foreseeable by the MTM pharmacist and the MTM management team, based on clinical judgment, quality control procedures, and those changes allowed per the program’s collaborative agreements, were included in the documentation system. This process was standardized, meaning that a particular problem was almost always associated with the same avoided medical service. Additionally, the estimates included only short-term (3-month) savings that might be realized as a direct result of an MTM encounter, not any longer-term savings that might have occurred as a result of implementing preventive drug therapies, such as aspirin to prevent myocardial infarction and stroke, calcium supplementation to prevent osteoporosis and fractures, or immunizations to prevent influenza or pneumonia.

As a quality control procedure, the cost savings claims were adjudicated by an independent clinical pharmacist, external to the Fairview system, who could disallow or downgrade the cost-savings estimate if evidence documented by the practitioner was insufficient. Each time an MTM pharmacist determined that a hospital admission, ER visit, or nursing home admission was avoided as a result of MTM, additional documentation of agreement by the patient and the patient’s primary physician was required. This method of estimating health care cost savings was included in the Isetts et al. study that assessed the validity of determinations made by Fairview MTM pharmacists.32

To estimate total cost avoidance, the expenses of the avoided health care services were linked to the average costs of services provided and charged by Fairview Health Services in the last quarter of 2008. Specifically, for each medical service, total avoided expense was calculated by multiplying the number of avoided services by the average cost per service. The value of avoiding lost work time was estimated by multiplying $30.00 (average hourly wage in Fairview) by 8 (daily working hours), then multiplying that result by the number of workdays gained by the intervention, as determined by the pharmacist. For a calculation of the return on investment (ROI) for the program, the cost of providing MTM services was determined by multiplying the average cost of an MTM visit in the last quarter of 2008 by the number of MTM consultations during the 10-year period. The ROI was calculated by dividing the pharmacist-estimated total health care savings by the cost of MTM visits in 2008.

Patient Satisfaction

Since 2001, patient satisfaction surveys have been administered biannually to all patients enrolled in the MTM program in that year. The survey consists of a 7-item questionnaire using a Likert-type scale with 5 options (i.e., agree, strongly agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree) that measures patients’ satisfaction with MTM services. Respondents are asked to evaluate the following statements: (1) The pharmacist provided me with education that will help me achieve my goals of therapy; (2) The pharmacist helped me to understand the intended use (purpose) of my medication(s); (3) The pharmacist helped me to understand the intended results (goals of therapy) of my medication(s); (4) The pharmacist helped me understand how to take my medication(s) safely and correctly; (5) I feel that my overall health and well-being improved because of my MTM visit; (6) Health care benefits should include MTM services; and (7) I would recommend this MTM service to my family and friends. Beneath the 7 statements, there is room for respondents to write comments and suggestions about the MTM program.

In 2008, only patients newly enrolled in the MTM program were surveyed after 2 visits with the MTM pharmacist. Patients received the surveys in the mail along with a pre-addressed postage-paid envelope. For the purposes of the present study, the results of the surveys administered from July to December 2008 were analyzed.

Results

From 1998 to 2008, there were 33,706 documented encounters in a cohort of 9,068 patients, yielding an average of 3.72 visits per patient. The patients ranged in age from 21 to 102 years with 55.5% of patients younger than age 65 years (Table 1). Females constituted 75.9% of the patients.

TABLE 1.

Patient Population Receiving Medication Therapy Management

| Patient Characteristics | Number of Patients (%)a N = 9,068 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2,184 (24.1) | |

| Female | 6,884 (75.9) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 21-50 | 2,018 (22.3) | |

| 51-64 | 3,019 (33.3) | |

| 65 or more | 4,031 (44.5) | |

| Number of medications at baselineb | ||

| 0 | 35 (0.4) | |

| 1-2 | 130 (1.4) | |

| 3-4 | 248 (2.7) | |

| 5-6 | 444 (4.9) | |

| 7-8 | 716 (7.9) | |

| 9-10 | 844 (9.3) | |

| More than 10 | 6,651 (73.3) | |

| Number of medical conditionsc | ||

| 0 | 217 (2.4) | |

| 1-2 | 1,015 (11.2) | |

| 3-4 | 1,269 (14.0) | |

| 5-6 | 1,741 (19.2) | |

| 7-8 | 1,605 (17.7) | |

| 9-10 | 1,135 (12.5) | |

| More than 10 | 2,086 (23.0) | |

| Number of drug therapy problems | ||

| 0 | 1,360 (15.0) | |

| 1 | 1,405 (15.5) | |

| 2 | 1,469 (16.2) | |

| 3 | 1,451 (16.0) | |

| 4 | 753 (8.3) | |

| 5 or more | 2,630 (29.0) | |

| Payer | ||

| Fairview enrollees | 6,196 (68.3) | |

| Private pay | 1,233 (13.6) | |

| Medicare Part D | 1,137 (12.5) | |

| Medicaid | 502 (5.5) | |

a Reflects patients who chose participation after receiving a mailed invitation from the MTM program. Columns may not sum to 100% due to rounding

b Total medication count includes chronic and acute prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, supplements, and herbal products.

c Count of medical conditions was based on the number of different International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes contained in the patient’s electronic medical record.

MTM = medication therapy management.

Medical Conditions and Drug Therapies Used

The average number of medical conditions being treated or prevented per patient through September 2008 was 6.8; 72.4% of patients had 5 or more conditions, and 23.0% had more than 10 conditions. The most frequent indications for drug therapy were hypertension (8.4%), hyperlipidemia (7.9%), nutritional/vitamin supplements (7.3%), diabetes (6.5%), osteoporosis (4.1%), depression (3.7%), and esophagitis (3.5%; data not shown).

The number of medications per patient ranged from 1 to 52. The mean (SD) number of medications per patient encounter was 12.4 (5.9). Forty-five percent of the patients (n = 4,081) were taking 59,427 different OTC medications, and 633 patients (7.0%) were also using 1,783 different sample products.

Drug Therapy Problems Identified and Addressed

The number of drug therapy problems identified and addressed by MTM pharmacists from 1998 to 2008 was 38,631. At the first MTM visit, 7,708 (85.0%) of patients had 1 or more drug therapy problems, and 2,630 (29.0%) had 5 or more drug therapy problems. The most frequent drug therapy problem was the need for additional drug therapy (28.1% of all drug therapy problems; Table 2). The majority of these problems involved patients who required preventive aspirin, oral calcium supplements, oral hypoglycemics, statins, or insulin. The second most common drug therapy problem category was subtherapeutic dosage (26.1% of all drug therapy problems). The top 5 categories of medications that were most commonly used in subtherapeutic dosages included oral hypoglycemics, insulin, calcium, statins, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Only 16.5% of drug therapy problems were attributed to nonadherence. In the pharmacist’s assessment of the single main cause for nonadherence, the most frequent cause of patients being unable or unwilling to take medications as intended was that the patient could not afford to purchase the medication or could not afford the copayment required to obtain the prescription (36.2% of 6,379 nonadherent patients; Table 3). The next most frequent reason identified for nonadherence was that the patient did not understand the instructions (24.8% of nonadherent patients). The top 5 categories of medications associated with nonadherence were statins, insulin, oral hypoglycemics, proton pump inhibitors, and ACE inhibitors.

TABLE 2.

Drug Therapy Problems Identified and Addressed by MTM Pharmacistsa

| Categories of Drug Therapy Problems | Number of Drug Therapy Problems (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Indication | 1. Unnecessary drug therapy | 2,196 (5.7) |

| 2. Needs additional drug therapy | 10,870 (28.1) | |

| Effectiveness | 3. Ineffective drug | 3,387 (8.8) |

| 4. Dosage too low | 10,100 (26.1) | |

| Safety | 5. Adverse drug reaction | 3,197 (8.3) |

| 6. Dosage too high | 2,502 (6.5) | |

| Compliance | 7. Nonadherence | 6,379 (16.5) |

| Total | 38,631 |

a Reflects services provided from September 1998 through September 2008 to 9,068 patients.

MTM = medication therapy management.

TABLE 3.

Drug Therapy Adherence Problems Addressed by MTM Pharmacistsa

| Drug Therapy Problem | Count (%) |

|---|---|

| Cannot afford drug product | 2,311 (36.2) |

| Patient does not understand instructions | 1,585 (24.8) |

| Patient prefers not to take | 1,014 (15.9) |

| Patient forgets to take | 806 (12.6) |

| Drug product not available | 546 (8.6) |

| Cannot swallow/administer | 117 (1.8) |

a Reflects MTM services provided from September 1998 through September 2008 to 9,068 patients with a total of 6,379 adherence problems. Table shows the problem that, in the opinion of the pharmacist, was the main reason that the patient was nonadherent. For patients with more than 1 reason, only the main reason is shown.

MTM = medication therapy management.

Eighty percent of drug therapy problems identified in Fairview’s MTM program were resolved without the direct involvement of patients’ physician(s), perhaps because the MTM program has collaborative practice agreements signed with physicians in Fairview Health Services. The most common resolutions of drug therapy problems with patients were education (35.8%), elimination of a barrier to access a medication (26.8%), initiation of a new drug therapy (11.8%), and change in dose (10.5%). The most frequent resolutions of drug therapy problems with physicians were initiation of a new drug therapy (32.4%), change in drug dosage (25.2%), change in drug product (14.7%), and discontinuation of a drug therapy (12.1%).

Clinical Outcomes

In the clinical status assessment of the 12,851 medical conditions in 4,849 patients who were not at goal when they enrolled in the MTM program, 7,068 conditions (55.0%) improved, 2,956 (23.0%) were unchanged, and 2,827 (22.0%) worsened during the course of MTM services. Of the 31,858 medical conditions evaluated on at least 2 occasions in 5,054 patients, 17,203 (54.0%) conditions were unchanged, 10,513 (33.0%) improved, and 4,141 (13.0%) declined in clinical status during MTM therapy.

In the subset of patients with diabetes (110 employees of a self-funded employer), 47 (42.7%) reached all D5 goals for diabetes (A1c less than 7%, blood pressure less than 130/80 mmHg, LDL-C less than 100 mg per dL, no tobacco use, and daily aspirin use) at the last MTM visit. At baseline, only 19 (17.3%) of these patients were reaching all goals, representing an absolute 25.4% change. By comparison, in Minnesota as a whole, only 8% and 13% of patients with diabetes who were covered by public and private payers, respectively, were reaching all these goals in 2008.38

Economic Outcomes

Over the 10-year study period, pharmacist-estimated direct savings to Fairview Health Services were $2,913,850 ($86.45 per encounter for 33,706 encounters; Table 4). The average cost of an MTM visit for Fairview was $67.00 in the last quarter of 2008, for a total MTM programmatic cost of $2,258,302 and an estimated ROI of $1.29 per $1 in MTM costs.

TABLE 4.

Estimated Health Care Savingsa

| Health Care Savings | Number of Events | Cost Per Event | Total Savings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic outpatient visit avoided | 10,313 | $162.00 | $1,670,706 |

| Specialty office visit avoided | 1,346 | $207.00 | $278,622 |

| Employee work days saved | 277 | $240.00 | $66,480 |

| Laboratory service avoided | 240 | $22.45 | $5,388 |

| Urgent care visit avoided | 144 | $121.24 | $17,459 |

| Emergency room visit avoided | 211 | $755.00 | $159,305 |

| Hospital admission avoidedb | 41 | $16,983.00 | $696,303 |

| Nursing home admissions | 3 | $6,398.00 | $19,194 |

| Home health visit | 1 | $392.84 | $393 |

| Total | 12,576 | $2,913,850 |

a Reflects services provided to 9,068 patients in 33,706 encounters from September 1998 through September 2008. Savings were calculated as the number of events avoided by MTM, as estimated by the MTM pharmacist and validated by external review, times the average costs of services at Fairview Health Services in the second quarter of 2008.

b Cost per event is the average cost of a hospital admission in Fairview Health Services in the second quarter of 2008.

MTM = medication therapy management.

Patient Satisfaction

From July to December 2008, 317 patients responded to the patient satisfaction survey (28.0% response rate of 1,132 surveys mailed), expressing a generally high level of satisfaction with the program: 97.1% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the pharmacist provided them with the education that will help them to achieve their goals of therapy; 95.3% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that their overall health and well-being had improved because of MTM; 98.1% of patients agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend this service to their family and friends; 99.0% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the pharmacist helped them to understand the intended use (purpose) of their medications; 99.9% of patients agreed or strongly agreed that the pharmacists helped them to understand the intended results (goals of therapy) of their medications; 99.0% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the pharmacist helped them to understand how to take their medication(s) safely and correctly; and 98.1% of patients agreed or strongly agreed that health care benefits should include the MTM program. Moreover, the patients’ comments about the MTM program were overwhelmingly positive, including a patient who commented that the MTM service had changed her life by permitting her to gain control of her diabetes.

Discussion

In a large integrated health care system, MTM was provided to a diverse group of 9,068 patients, using a standardized patient care process to address numerous drug therapy problems identified by pharmacists. In this population, patients rarely experienced a single medical condition, and 72% had 5 or more medical conditions. The high level of comorbidities makes patients’ drug regimens complex, which can make adherence difficult and confusing for patients. Focusing on only a single disease state is unlikely to adequately meet all of a patient’s drug-related needs.

Moreover, despite extensive use of nonprescription medications (OTC, supplements, herbal medicines, etc.) by this population, those drug products are usually not recorded in standard payer claims database systems or pharmacy dispensing systems. MTM is an effective mechanism to facilitate assessment of the indications, effectiveness, and safety of OTC products, especially in patients who are using multiple prescription medications.

More than one-half (54.2%) of drug problems involved the need for a new medication or dosage increase. The medical conditions associated with these most common drug therapy problems were diabetes and hyperlipidemia. These results suggest that when pharmacist practitioners work closely and over time with patients to facilitate reaching the goals of therapy, there is usually an increase in medication use. These results are consistent with those of previous research that assessed the clinical outcomes of pharmaceutical care services.19,31,39,40 For example, Welch et al. found that Medicare Part D beneficiaries who opted in to receive MTM were more likely to incur an increase in medication costs than were those who opted out of MTM.19 These results also indicate that health care providers might choose nonpharmacological interventions when drug therapy is needed or use a dose that is too low to control the patient’s medical condition. Other studies have shown a failure to titrate medications, such as statins, to effective doses in patients at risk of complications.41,42 Some authors who stress the importance of using more aggressive therapy, such as higher doses or introducing combination therapy to get patients to goal, have described “clinical inertia,” a failure of health care providers to initiate or intensify therapy when indicated.43,44

Even though most work conducted within pharmacy has focused on adverse drug effects, drug interactions, duplicate therapy, and compliance, our data suggest that the major problem related to medications can be attributed to underuse of potentially efficacious drug therapy. As stated by O’Connor et al. (2005), failure to intensify therapy in patients with chronic conditions and suboptimal biomarker readings for blood glucose, blood pressure, or serum lipids represents a type of medication error as defined by the Institute of Medicine by leading to adverse events.44 O’Connor et al. assert that the main distinction between the adverse events caused by overuse or misuse of therapies, and adverse events caused by underuse of therapies in chronic disease care, is the time frame over which the adverse event occurs. Clinical inertia, or the underuse of efficacious drug therapy, “may take years or even decades for the consequent adverse event to declare itself.”44

The Fairview MTM program’s experience suggests that patients often have good reason for not adhering or persisting with drug treatment. As discussed by Ramalho de Oliveira and Shoemaker (2006), pharmacists should look at noncompliance from the perspective of the patients, taking into consideration their subjective experiences with their illnesses and medications.45 In this context, it is essential to understand the patient’s unique medication experience, which is connected with patients’ previous experiences with medications, what they think and feel about their medications, and their concerns and beliefs about them.46 This experience will influence the patient’s decisions about whether to take the medication, to decrease or increase the dose, or to make necessary modifications to the drug regimen. In a recent review on compliance and adherence, Touchette and Shapiro (2008) suggested that because adherence is a multifaceted issue, programs designed to impact adherence should focus on identifying patient-specific adherence barriers and tailor interventions to eliminate or reduce these barriers.47 The authors emphasize that tailoring interventions to meet each patient’s needs will bring about better outcomes than offering the same blanket intervention to all patients.47 This review corroborates the approach of using the patient’s unique medication experience to assist him or her to achieve therapeutic goals.

Stebbins et al. (2005) examined pharmacists’ interventions that combined drug utilization review with patient and physician education in a medical clinic for low-income elderly patients.48 In this study, pharmacists’ interventions increased the use of generic drugs, decreased out-of-pocket drug expenses by patients, and promoted use of needed treatments. Another study by Barnett et al. (2009) that analyzed 7 years of MTM claims from an MTM administrative services company suggested that from 2000 to 2006, there was a shift in the type of pharmacists’ interventions from patient education involving acute medications to prescriber consultation for chronic medications.49 Barnett et al. also found an increase in the MTM reimbursement over time, from $7.65 to $12.28 per intervention. As underscored by Benner and Kocot (2009), we are moving towards a health care system that will emphasize and reward quality and high value, and pharmacists must take the opportunity to redefine themselves as medication therapy managers who will add significant value by improving medication outcomes.50 The profession of pharmacy must focus on the unmet needs of patients and provide consistent and standardized services that can be recognized, measured, and paid for.

The economic results of this study were positive as the calculated ROI suggests that MTM services decreased the total cost of health care in Fairview Health Services. Our results are similar to those of other studies that also indicated potential cost-saving effects of MTM services.34,49

This study is an important step in the direction of examining the outcomes of a comprehensive, standardized, and holistic approach to MTM. As stressed by Doucette et al. (2005),39 policy makers seeking models of MTM services for Medicare beneficiaries should consider a model as comprehensive as pharmaceutical care for patients at high risk of developing drug-related problems.

Currently, MTM pharmacists are considered an indispensable part of the health care team in Fairview Health Services because they assume responsibility for patients’ drug therapy outcomes and collaborate with other providers to facilitate high-quality patient care. In 2010, Fairview’s MTM program is expanding to 6 additional clinics, and 3 MTM pharmacists are providing care on-site at major employers’ headquarters in the Twin Cities area.

Limitations

First, the lack of a comparison group makes this a descriptive study without the ability to attribute outcomes to the MTM interventions. Participating patients opted into the program and therefore might be especially motivated to comply with medical and drug treatments. Second, the economic outcomes described here are the result of a process of estimation and documentation by MTM pharmacists, which is based on clinical judgment instead of a thorough analysis of medical claims. Third, our programmatic cost estimates do not include additional costs associated with added medications or increased dosages. Fourth, because our survey response rate was low, the satisfaction level of survey respondents might not reflect that of the MTM population as a whole. Fifth, our results may be partly attributable to the collaborative practice agreements that permitted pharmacists to make 80% of interventions without physician involvement. A final limitation is the inability to generalize the findings outside of the health system environment where access to needed patient information is not as readily available.

Conclusion

The pharmaceutical care-based MTM services assessed in this study identified numerous drug therapy problems; 85% of patients had 1 or more drug therapy problems, and 29% had 5 or more drug therapy problems. Because the most prevalent drug therapy problems were related to the underuse of effective medications, the number of medications used by patients tends to increase with MTM services. However, MTM may save total health care costs by helping patients avoid office visits, ER visits, and hospitalizations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, Pub. L. No. 108-173, 117 Stat. 2066 (January 7, 2003). Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MMAUpdate/downloads/hr1.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2010.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Part D medication therapy management (MTM) programs 2009 fact sheet. Updated July 21, 2009. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/MTMFactSheet.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2010.

- 3.Hassol A, Shoemaker SJ. Exploratory research on medication therapy management: final report. July 8, 2008. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/Reports/downloads/Blackwell.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2010.

- 4.Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual, Chapter 7–Medication Therapy Management and Quality Improvement Program. December 1, 2006. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/PDBManual_Chapter7.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2010.

- 5.Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical Care Practice. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998:359. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. Pharmaceutical Care Practice: The Clinician’s Guide. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004:394. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(3):533-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hepler CD. The future of pharmacy: pharmaceutical care. Am Pharm. 1990;NS30(10):23-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomechko MA, Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ. Q and A from the Pharmaceutical Care Project in Minnesota. Am Pharm. 1995;NS35(4):30-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hepler CD, Strand LM, Tromp D, Sakolchai S. Critically examining pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2002;42(5 Suppl 1):S18-S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramalho de Oliveira D. Pharmaceutical care uncovered: an ethnographic study of pharmaceutical care practice. [dissertation]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strand LM, Cipolle RJ, Morley PC, Frakes MJ. The impact of pharmaceutical care practice on the practitioner and the patient in the ambulatory practice setting: twenty-five years of experience. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10(31):3987-4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGivney MS, Meyer SM, Duncan-Hewitt W, Hall DL, Goode JV, Smith RB. Medication therapy management: its relationship to patient counseling, disease management, and pharmaceutical care. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2007;47(5):620-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]