Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and confirmed feline McDonough sarcoma (FMS)-like tyrosine kinase 3 gene mutations (FLT3mut+) have a poor prognosis and limited effective treatment options. Gilteritinib is the first targeted therapy approved in the United States and Europe for R/R FLT3mut+ AML with significantly improved efficacy compared with existing treatments.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate gilteritinib against salvage chemotherapy (SC) and best supportive care (BSC) over a lifetime horizon among adult patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML from a US third-party payer’s perspective.

METHODS:

The model structure of this cost-effectiveness analysis included a decision tree to stratify patients based on their hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) status, followed by 2 separate 3-state partitioned survival models to predict the long-term health status conditional on HSCT status. The ADMIRAL trial data and literature were used to predict probabilities of patients being in different health states until a conservative cure point at year 3. Afterwards, living patients followed the survival outcomes of long-term survivors with AML.

Model inputs for utilities, medical resource use, and costs were based on the ADMIRAL trial, published literature, and public sources. All costs were inflated to 2019 US dollars (USD). Total incremental costs (in 2019 USD), life-years (LYs), quality-adjusted LYs (QALYs), and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated. Deterministic sensitivity analyses and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed.

RESULTS:

Over a lifetime horizon with a 3.0% annual discount rate, the base-case model estimated that gilteritinib led to an increase of 1.29 discounted QALYs at an additional cost of $148,106 vs SC, corresponding to an ICER of $115,192 per QALY; for BSC, results were an increase of 2.32 discounted QALYs, $249,674, and $107,435, respectively. The base-case findings were robust in sensitivity analyses. The estimated probabilities of gilteritinib being cost-effective vs SC and BSC were 90.5% and 99.8%, respectively, in the probabilistic sensitivity analyses, based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150,000 per QALY.

CONCLUSIONS:

Gilteritinib is a cost-effective novel treatment for patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML in the United States.

What is already known about this subject

Relapsed or refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with confirmed feline McDonough sarcoma (FMS)-like tyrosine kinase 3 gene mutations (FLT3mut+) is associated with a poor prognosis, and few options exist for effective therapy.

Gilteritinib, a targeted therapy for R/R FLT3mut+ AML, demonstrated significantly improved efficacy compared with existing salvage chemotherapy (SC) treatments in the pivotal ADMIRAL trial.

What this study adds

This study evaluated the cost-effectiveness of gilteritinib against SC and best supportive care (BSC) for patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML, using inputs from the ADMIRAL trial and the literature.

Over a lifetime horizon with a 3.0% annual discount rate, the base-case model estimated that gilteritinib led to increases of 1.29 and 2.32 discounted quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) over SC and BSC, respectively.

Gilteritinib was associated with additional costs of $148,106 vs SC and $249,674 vs BSC, corresponding to incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of $115,192 and $107,435 per QALY, respectively; it was estimated to be cost-effective against SC and BSC with more than 90% probability based on a willingness-to-pay threshold of $150,000 per QALY.

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogeneous hematologic malignancy of hematopoietic precursor cells from the myeloid lineage.1 It is the most common form of adult leukemia (~80%), and in the United States, has an incidence of 3 to 5 cases per 100,000 people.2 Although the response rates to first-line chemotherapy are high, the majority of newly diagnosed patients with AML will ultimately relapse or develop refractory (R/R) disease. Patients with R/R AML who have confirmed feline McDonough sarcoma (FMS)-like tyrosine kinase 3 gene mutations (FLT3mut+) experience particularly poor prognoses and have limited treatment options.3,4

The conventional treatment pathways for patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML historically included initial induction with salvage chemotherapy (SC) followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) when suitable.5 Commonly used SC options include fludarabine + cytarabine + granulocyte colony-stimulating factor + idarubicin (FLAG-IDA), mitoxantrone + etoposide + cytarabine (MEC), azacitidine, and low-dose cytarabine (LoDAC).5-7 The choice of SC regimen depends on many patient factors such as age, patient preference, goals of care (curative vs palliative), comorbidities, and prior treatment history.4,8

Patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML treated with SC have generally experienced poor clinical outcomes, characterized by low response rates and dismal survival.8-10 Due to limited efficacy and tolerability concerns of SC regimens, a substantial proportion (11%-40%) of patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML are reported to receive best supportive care (BSC), defined as palliative care with no active leukemia-directed therapy, in actual clinical practice.7,11 Patients managed with BSC still incur substantial resource use and worse outcomes compared with those receiving SC.12

In November 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration approved gilteritinib as the first targeted therapy for the treatment of R/R FLT3mut+ AML, and its approval has resulted in a paradigm shift in the management of this difficult-to-treat disease. Gilteritinib is a novel, oral, highly selective type I inhibitor of FLT3.13-15 The efficacy of gilteritinib was assessed in the ADMIRAL trial,16 where patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML were randomized to receive either gilteritinib or investigator prespecified SC (ie, azacitidine, FLAG-IDA, MEC, and LoDAC). Gilteritinib was associated with significantly better outcomes compared with the SC, including longer median overall survival (OS; 9.3 vs 5.6 months) and higher rates of 1-year survival (37.1% vs 16.7%), and a higher proportion of patients treated with gilteritinib proceeded to HSCT (25.5% vs 15.3%; all P < 0.05).

In addition, the composite complete remission (CR) rate (CRc), combined rate of CR and CR with partial hematologic recovery (CR/CRh), and the overall response rate more than doubled in the gilteritinib arm compared with the SC arm (CRc: 54.3% vs 21.8%; CR/CRh: 34.0% vs 15.3%; overall response rate: 67.6% vs 25.8%). Gilteritinib was also associated with fewer hospitalizations compared with SC, and 34.5% of patients in the gilteritinib arm became transfusion independent (no red cell or platelet transfusions administered for 56 consecutive days) after treatment.16 These benefits have been directly linked to improvements in patient quality of life.6,17,18

Although the ADMIRAL trial has clearly demonstrated the clinical benefit of gilteritinib, the economic value of gilteritinib in R/R FLT3mut+ AML has not been fully evaluated in the United States.19,20 Such evidence would help inform payers’ decision-making for R/R FLT3mut+ AML and help weigh this novel therapy against conventional treatments. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a cost-effectiveness study to compare the economic value of gilteritinib with that of SC and BSC for the treatment of adult patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML over a lifetime horizon from a US third-party payer’s perspective.

Methods

MODEL OVERVIEW

A decision tree followed by a partitioned survival modeling approach was used to assess the cost-effectiveness of gilteritinib vs SC and BSC, the 2 most common conventional treatment options, among adult patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML (Figure 1). The SC comparator in the base-case analysis was composed of a mixture of azacitidine (25.8%), FLAG-IDA (33.9%), MEC (26.6%), and LoDAC (13.7%). The weights for therapies were based on data from the ADMIRAL trial.16

FIGURE 1.

Model Framework

The model was conducted from a US third-party payer’s perspective; thus, only direct costs were included in the analysis. The base-case analysis considered a lifetime horizon, with costs and effectiveness discounted at 3% annually. The model structure included a decision tree to stratify patients based on their HSCT status, followed by 2 separate 3-state partitioned survival models to predict the longterm health status conditional on HSCT status (Figure 1). All patients began in the “treatment alone without HSCT” state following treatment initiation, and a proportion of patients were partitioned to the “with HSCT” state based on observations reported in the ADMIRAL trial. Each partitioned survival model included 3 health states: event-free survival (EFS), postevent, and death. The definition of EFS and OS was reported in the ADMIRAL trial publication.16 The selected model structure was chosen because HSCT has a significant impact on treatment outcomes for the target patient population.

MODEL ASSUMPTIONS

Subsequent HSCTs after initial treatments were assumed to directly impact patient OS and EFS, and the efficacy outcomes following HSCT were assumed to be independent of the initial treatment prior to HSCT. Patients treated with BSC were assumed to start in the “alive and postevent” state following treatment initiation, as these patients were considered to have a low likelihood of achieving response.

The model conservatively assumed that patients who remained alive after year 3 were long-term survivors, following a range of publications describing “cure” as likely in patients surviving beyond 18 to 36 months.21-30 These patients would have a 2-fold increase in mortality rate compared with the general population based on literature, and they incurred health state-specific costs and utility based on the same set of inputs applied to patients in the state of EFS with HSCT.

Patients were treated based on the treatment schedules and duration specified in the ADMIRAL trial,16 which were considered to be representative of US practice.31 Patients in the gilteritinib arm could continue to receive gilteritinib after HSCT per the ADMIRAL trial’s design. Both the costs and benefits associated with post-HSCT gilteritinib treatment continuation were considered in the model.

Utilities of health states were assumed to be dependent only on health states and independent of treatment arms. Patients were assumed to incur different medical costs by health states and treatment arms. A proportion of the patients in the “postevent with HSCT” and “post-event without HSCT” states were also assumed to receive subsequent active treatment and incur postprogression treatment costs. In addition, patients incurred 1-time terminal care costs before death. Costs and disutilities associated with grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs) were considered in the model, given these are typically considered to have nontrivial effects on costs and QALYs. Grade 1/2 AEs were not considered due to the expectation they would have minor effects on costs and QALYs.

MODEL INPUTS

Efficacy Inputs. OS and EFS Without HSCT: For gilteritinib, OS and EFS without HSCT inputs were estimated based on patient-level data from the ADMIRAL trial among patients who did not receive subsequent HSCT. Parametric survival models, including exponential, Weibull, log-logistic, log-normal, Gompertz, and generalized gamma survival distributions, were estimated to predict proportions of patients in different health states over time. Log-logistic distribution was selected in the base-case based on best model fit.

For SC, OS and EFS without HSCT were derived from the predicted survival curves of the gilteritinib arm without HSCT by applying hazard ratios (HRs) based on data from the ADMIRAL trial (HR for OS = 1.64; HR for EFS = 2.82, Supplementary Table 1 (84.3KB, pdf) , available in online article).16 These HRs were applied to the OS and EFS curves of the gilteritinib arm to derive the corresponding curves for the SC comparator (Table 1).16

TABLE 1.

Key Model Inputs

| Model inputa | Value | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratios | ||

| OS without HSCT, SC vs gilteritinib | 1.64 | • ADMIRAL trial16,b |

| OS without HSCT, BSC vs gilteritinib | 2.86 | • ADMIRAL trial16,b and Sarkozy et al32,b |

| EFS without HSCT, SC vs gilteritinib | 2.82 | • ADMIRAL trial16,b |

| OS with HSCT, with post-HSCT gilteritinib vs without post-HSCT gilteritinib | 0.69 | • ADMIRAL trial16,b and Evers et al33,b |

| Efficacy inputs | ||

| OS without HSCT, gilteritinib | Parametric survival model | • ADMIRAL trial16 |

| EFS without HSCT, gilteritinib | Parametric survival model | • ADMIRAL trial16 |

| OS with HSCT without post-HSCT gilteritinib | Parametric survival model | • Evers et al33 |

| Utility inputs for health statesc | ||

| EFS without HSCT | 0.84 | • ADMIRAL trial16 |

| Postevent without HSCT | 0.77 | |

| EFS with HSCT | 0.86 | |

| Postevent with HSCT | 0.80 | |

| Long-term survivors | 0.86 | |

| Age-related utilitiesc | ||

| Age 55-64 years | 0.83 | • Janssen et al 201438 |

| Age 65-74 years | 0.82 | |

| Age ≥ 75 years | 0.76 | |

| Disutility associated with AEsc | ||

| Gilteritinib | −0.21 | • Swinburn et al 2010,59 Doyle et al,40 Lloyd et al,41 and Joshi et al43 |

| SC | −0.14 | |

| BSC | 0.00 | |

| Monthly drug acquisition and administration costs, $ | ||

| Gilteritinib | 23,784 | |

| SC | 2,909 | |

| BSC | 0 | |

| Monthly medical costs by health states, $ | ||

| EFS without HSCT, gilteritinib | 5,279.69 | |

| EFS without HSCT, SC | 20,186.34 | |

| EFS without HSCT, BSCd | NA | |

| Postevent without HSCT | 15,701.23 | |

| EFS with HSCT | 285.89 | |

| Postevent with HSCT | 15,701.23 | |

| Long-term survivors | 285.89 | |

| Adverse event-related costs associated with initial treatment, $ | ||

| Gilteritinib | 33,934.42 | |

| SC | 24,661.71 | |

| BSC | 0.00 | |

| Subsequent HSCT inputs, % | ||

| Patients with subsequent HSCT on gilteritinib arm | 25.50 | • ADMIRAL trial16 |

| Patients with subsequent HSCT on SC arm | 15.30 | |

| Patients with subsequent HSCT on BSC armd | 0.00 | • Assumption |

| HSCT costsc | $117,904.15 | • Medicare provider utilization and payment data63 |

| Disutility from HSCTc | –0.21 for 6 months | • Joshi et al43 |

| Other cost inputs,c $ | ||

| Postprogression treatment costs, gilteritinib | 11,043.30 | |

| Postprogression treatment costs, SC | 14,665.02 | |

| FLT3 testing costs | 248.51 | • CMS clinical diagnostic laboratory fee schedule64 |

| Terminal care costs | 16,296.25 | • Olszewski et al65 |

Note: All costs are reported in 2019 US dollars.

aUnless otherwise specified, the above inputs apply to both gilteritinib and SC arms.

bSee Supplementary Table 1 (84.3KB, pdf) for detailed calculation (available in online article).

cThese cost and disutility inputs were applied once in the model upon the occurrence of the associated events.

dIt was assumed that patients treated with BSC started in the postevent state, no patient received subsequent HSCT following treatment initiation, and no patient would receive active antileukemic treatment after progression.

BSC = best supportive care; CMS = Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; EFS = event-free survival; FLT3 = FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; HCUP = Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project; HSCT = hematopoietic stem cell transplant; NA = not applicable; OS = overall survival; SC = salvage chemotherapy.

Because the ADMIRAL trial did not evaluate BSC as a comparator, published literature was used to inform its efficacy.20 Specifically, Sarkozy et al was selected from a targeted literature review as the most relevant publication because it evaluated the efficacy of BSC in a comparable population (ie, patients with R/R AML, although the study did not differentiate FLT3mut+ status) and included a large sample who received BSC (N = 124).20 The HR of 2.86 was applied to the predicted OS curve of the gilteritinib arm to derive the OS without HSCT input for the BSC comparator (Supplementary Table 1 (84.3KB, pdf) ).16,32 EFS was not estimated for BSC since patients were assumed to not have achieved a response with BSC, and they started from the postevent states upon model entry.

OS and EFS With HSCT: For patients who received HSCT, the efficacy inputs were based on Evers et al, which included a patient population similar to the ADMIRAL trial but had a larger sample size (N = 128) and longer follow-up time (median 6.5 years), to reliably inform the long-term survival trajectory of patients with R/R AML undergoing HSCT.33 In the ADMIRAL trial, 82 patients received HSCT, and the follow-up post-HSCT survival for these patients was limited (ie, a median of 7.5 months with only 2 patients [3%] having data beyond year 2). Therefore, the data from Evers et al were considered more robust to inform OS and EFS for patients with HSCT.

Standardized parametric functions were fitted to project the survival estimates for OS with HSCT, and gamma distribution was selected in the base-case based on best model fit. EFS data were not reported in Evers et al and was instead estimated based on OS data assuming a constant proportion in the cumulative hazard function.

Evidence suggested that patients with FLT3mut+ AML undergoing HSCT could benefit from maintenance with FLT3 inhibitors posttransplantation.34-36 As the only available data to assess the impact of post-HSCT gilteritinib, the ADMIRAL trial data were used to inform the benefit of post-HSCT gilteritinib bearing the limitation of a small sample size and limited follow-up time. The HR of 0.69 was estimated comparing patients with post-HSCT gilteritinib from the ADMIRAL trial with those without such treatment using data from Evers et al16,33; the HR was applied to the proportion of patients continuing gilteritinib treatment after HSCT (Supplementary Table 1 (84.3KB, pdf) ).

Long-term Survival After Year 3: In the base-case model, parametric or HR-based survival modeling approaches were used to model the probabilities of patients being alive for the first 3 years. Afterwards, patients who remained alive were considered long-term survivors. Existing literature suggests that plausible cure points for patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML range from 18 months to 3 years, after which point patients would have limited risk of relapse.21-30 In the current model, we conservatively assumed all patients would become long-term survivors after year 3. These patients would have a 2-fold increase in mortality rate compared with the general population.

Utility Inputs. Utility and disutility input values are summarized in Table 1. The EuroQoL Group 5-dimension 5-level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L) data collected in the ADMIRAL trial were converted to 3-level (EQ-5D-3L) data following the position statement from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,37 which were subsequently used to estimate the utilities for different health states. Because the health state utilities were estimated based on the trial population with a median age of 62 years, additional age-related utility decrements based on Janssen et al were also applied to the model as the population became older over the lifetime horizon.38

In addition, disutilities associated with grade 3/4 AEs and the HSCT procedure were considered in the base case. Disutility values for each AE were obtained from the literature and were applied for the first cycle when patients received the corresponding treatments.39-42 The disutility input for the HSCT procedure based on Joshi et al BSC was assumed to have no associated disutilities for AEs or HSCT.43

Cost Inputs. The model considered costs of drug acquisition and administration, AEs, subsequent HSCT, health state-specific medical resource use, FLT3 testing, post-progression treatment, and terminal care (Table 1). Costs were reported in or inflated to 2019 US dollars (USD), with the exception of drug costs, which reflected 2020 costs. Drug acquisition and administration costs were estimated based on the dosing schedules, dosing intensities, and treatment durations observed in the ADMIRAL trial.16 Drug unit costs were based on average wholesale acquisition cost from IBM’s RED BOOK Micromedix.44 Unit costs of drug administrations were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Physician Fee Schedule.45 For SC, the drug acquisition and administration costs were calculated as a weighted average of the regimen-specific costs, with weights based on ADMIRAL trial data.16 BSC was assumed to incur zero drug acquisition or administration costs.

Costs related to grade 3/4 AEs were considered for the gilteritinib and SC arms. The AE rates were based on ADMIRAL trial data, while the AE unit costs were based on the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project databases or literature.16,46-49 BSC was assumed to have no associated AE costs. Postprogression treatment cost was estimated based on unit cost and the proportion of patients with postprogression treatment. The unit cost for postprogression treatment was informed by Hagiwara et al and was assumed to be the same for all arms.50 The proportion of patients receiving postprogression treatments in the gilteritinib and SC arms were from the ADMIRAL trial data; no patients in the BSC arm were assumed to have received any postprogression treatment. Other costs considered were calculated based on the ADMIRAL trial,16 public data sources, and published literature (see Table 1 for a full list).

MODEL OUTPUTS

Base-Case Analysis. Total costs were calculated separately for gilteritinib and comparators as the sum of individual cost inputs. Total life-years (LYs) and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were aggregated across treatment arms over the modeled time horizon. QALYs were estimated as the time spent in each state weighted by the utility of each state. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated as the total incremental costs per LY and QALY gained.

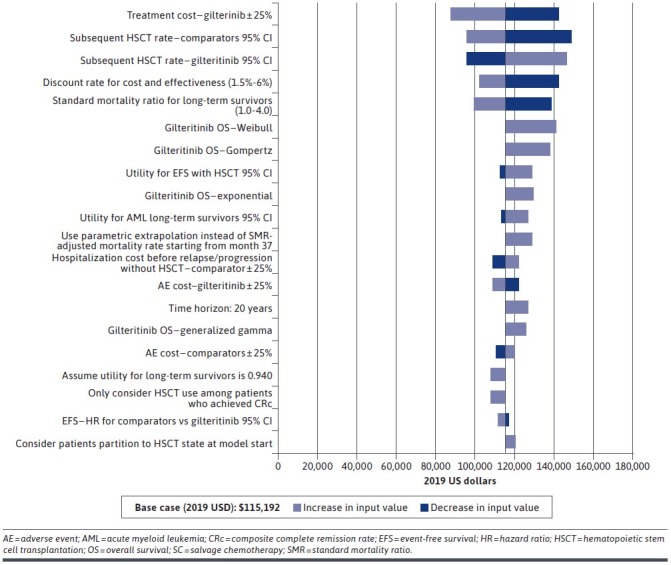

Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis. To assess the robustness of the model results, deterministic sensitivity analyses (DSA) were conducted by varying 1 model input or assumption at a time while holding other assumptions or parameters the same as in the base-case scenario. The specific model parameters were varied by the 95% CI or by the range if such information was reported in the original source. Otherwise, the modeled parameters were varied by plus or minus 25%, per assumption, from the base-case inputs. The DSA also evaluated different efficacy assumptions and cost scenarios. A detailed list of parameters and the corresponding ranges and assumptions in the DSA are provided in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1 (84.3KB, pdf) (available in online article).

FIGURE 2.

Deterministic Sensitivity Results (Gilteritinib vs SC)

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine the probability for gilteritinib to be cost-effective compared with each comparator on different willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds. A Monte-Carlo simulation with 1,000 iterations was conducted. In each iteration, key efficacy, utility, and cost inputs were randomly drawn from the specified distribution and varied so as to inform the possible range of the inputs. Correspondingly, an ICER was calculated in each iteration and compared with a WTP threshold of $150,000/QALY, a frequently used threshold to value new drugs in the US context by organizations such as the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review.51 The results were presented in a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve.

Results

BASE-CASE RESULTS

Over a lifetime horizon, patients treated with gilteritinib were expected to incur a total cost of $327,736, compared with $179,630 for SC and $78,062 for BSC (Table 2). The primary cost driver for gilteritinib was the treatment cost, while medical costs were the primary drivers for SC and BSC (Supplementary Figure 2 (84.3KB, pdf) , available in online article). In terms of effectiveness, gilteritinib was associated with 2.58 QALYs, compared with 1.29 QALYs for SC and 0.25 QALY for BSC. The corresponding ICERs for gilteritinib were $115,192/QALY relative to SC and $107,435/QALY relative to BSC.

TABLE 2.

Base-Case Result of the Model

| Gilteritinib | SC | BSC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost-effectiveness | |||

| Total discounted costs, $ | 327,736 | 179,630 | 78,062 |

| Total discounted LYs | 3.15 | 1.60 | 0.33 |

| Total discounted QALYs | 2.58 | 1.29 | 0.25 |

| Incremental costs, $ | − | 148,106 | 249,674 |

| Incremental LYs | − | 1.55 | 2.82 |

| Incremental QALYs | − | 1.29 | 2.32 |

| Incremental cost per LY gained, $ | − | 95,269 | 88,484 |

| Incremental cost per QALY gained, $ | − | 115,192 | 107,435 |

Note: All costs are reported in 2019 US dollars.

BSC = best supportive care; LY = life-year; SC = salvage chemotherapy; QALY = quality-adjusted life-year.

DETERMINISTIC SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

The model’s results remained robust to alternative inputs and assumptions in the DSA. Across all scenarios evaluated, the ICER results for gilteritinib ranged from $87,736 to $148,713 compared with SC, and $92,245 to $131,456 compared with BSC. Notably, in all scenarios, the ICER was less than $150,000/QALY. The model was most sensitive to the treatment cost of gilteritinib and the discount rate. The top drivers of change in the DSA are summarized and presented by treatment in Figure 2 (SC) and Supplementary Figure 1 (84.3KB, pdf) (BSC).

PROBABILISTIC SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

The estimated probabilities of gilteritinib being cost-effective vs SC and BSC were 90.5% and 99.8%, respectively, based on a WTP threshold of $150,000/QALY (Figure 3 [SC] and Supplementary Figure 3 (84.3KB, pdf) [BSC], available in online article).

FIGURE 3.

Cost-Effectiveness Acceptance Curve (Gilteritinib vs SC)

Discussion

Before the introduction of effective targeted therapies, the conventional treatment pathway for R/R FLT3mut+ AML was limited to SC regimens with dismal clinical outcomes and high toxicity profiles. In clinical practice, many patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML, who did not receive SC, were treated by BSC and had even worse clinical outcomes compared with SC regimens. Thus, the addition of gilteritinib as a novel and effective treatment for R/R FLT3mut+ AML fulfills a substantial unmet need for this patient population. Patients receiving gilteritinib in the ADMIRAL trial experienced prolonged survival (median OS of 9.3 months vs 5.6 months), and improved quality of life. While gilteritinib is a promising treatment option with a superior clinical profile vs SC for R/R FLT3mut+ AML, it is also associated with higher drug costs compared with SC. Thus, understanding its cost-effectiveness compared with existing treatment options for R/R FLT3mut+ AML is important for the decision-making processes of payers and policymakers. This study is the first to assess the cost-effectiveness of gilteritinib from a US third-party payer’s perspective.

The present cost-effectiveness model estimated that, over a lifetime horizon, patients treated with gilteritinib had a total incremental cost of $148,106 compared with patients treated with SC, and $249,674 compared with those treated with BSC. Although gilteritinib was associated with higher treatment costs than either comparator, it had lower associated medical costs compared with SC and BSC after adjusting for differences in survival times. The medical cost offset mainly resulted from the benefit of the reduced transfusion burden and hospitalization stays. Transfusion support represents a major cost driver in the management of AML.52 Our model estimated that patients in the post-EFS states require 47% more blood transfusions than those in the EFS states based on findings from Griffin et al.7 Patients receiving gilteritinib experienced prolonged EFS, which lead to reduced blood transfusion burden. The clinical benefits of gilteritinib were reflected in estimated gains of 1.55-2.82 LYs and 1.29-2.32 QALYs over a lifetime horizon. Considering both cost and clinical outcomes, gilteritinib was associated with ICERs of $115,192/QALY and $107,435/QALY compared with SC and BSC, respectively.

This study’s design has several distinct features that allow it to provide robust estimates to aid payers in their decision-making. First, the key inputs of the model were informed from the ADMIRAL trial data, which provided reliable information regarding the comparative clinical efficacy of gilteritinib vs SC in R/R FLT3mut+ AML. Second, based on the prognostic impact of HSCT on survival outcomes, the model structure considered HSCT to be a key clinical event that could directly impact treatment outcomes. Third, the treatment comparators considered in the analysis are reflective of the real-world treatment landscape. Finally, conservative assumptions were made in the base-case scenario, and extensive sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the results. For example, patients were considered long-term survivors after year 3 and followed the same mortality risk regardless of initial treatment. This assumption conservatively assumed that there were no additional clinical benefits for gilteritinib compared with SC after year 3.

Health systems and governments often set WTP thresholds to identify interventions that are relatively more cost-effective in order to maximize the allocation of limited resources. There is currently no consensus on the WTP in the United States. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review uses a range of $100,000/QALY to $150,000/QALY as the value-based price benchmark, and this range has since been widely cited.53 For rare diseases with large unmet treatment needs, the appropriate threshold used to evaluate these conditions tends to be higher than the threshold used for regular interventions. For example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence proposed a WTP threshold for rare diseases that is 3 to 5 times higher than nonrare diseases.54 Because R/R FLT3mut+ AML is a rare disease per the standards of the US National Institutes of Health, with limited effective therapy options, the upper threshold of $150,000/QALY was considered an appropriate yet conservative WTP threshold in this study. The present ICER estimates for gilteritinib ($107,435 vs BSC and $115,192 vs SC) fall under the threshold of $150,000/QALY, indicating that it is a cost-effective option in the United States.

In recent years, there has been a surge in the development of targeted therapies for patients with AML. While these agents have the potential to change the existing treatment landscape, they are typically also associated with higher costs. As this is the first cost-effectiveness study on therapies for patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML, currently there are no other studies to compare the present results with. However, there are several recent economic evaluations of novel treatments for other indications related to AML. For example, Stein et al estimated an ICER of $61,167/QALY for midostaurin in treating newly diagnosed FLT3mut+ AML.55 This estimate is not directly comparable to ours as it was estimated based on a patient population with less severe disease conditions, and midostaurin has limited clinical benefits in treating R/R FLT3mut+ AML.3

Several other studies focusing on AML populations with more severe disease conditions (eg, patients aged > 60 years) have reported ICERs between $111,385/QALY and $189,000/QALY.55-57 Thus, the ICERs for gilteritinib are on the lower end of the published range compared with other treatments for AML, further supporting its cost-effectiveness. A new set of age-related utility values by Jiang et al recently became available.58 The new set of utilities differs slightly from the estimates used in the current model. Using this new set of utilities (age 55-64 years: 0.815; age 65-74 years: 0.824; age ≥ 75 years: 0.811), the ICER decreased slightly from $115,192 to $112,097. This further supports the robustness of the study results.

LIMITATIONS

While the present study provides important observations, the results should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. First, different data sources were used to describe resource utilization for different health states and across treatments. However, these inputs represented the best available evidence, and the values were further validated by clinicians. Extensive sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the impact of alternative inputs. Furthermore, drug costs were in 2020 USD, and other costs were in 2019 USD. Future analyses updating these costs to 2021 USD could be valuable.

Second, the potential benefit of gilteritinib as an oral therapy was not fully accounted for in this model. Patients receiving gilteritinib are expected to incur less travel to seek care and spend less time in the hospital, which could improve patients’ work productivity and alleviate caregiver burden. It is anticipated that the inclusion of this benefit would make gilteritinib ICER estimates even more favorable.

Third, the HSCT survival data from the ADMIRAL trial were immature and could not be directly incorporated into the efficacy inputs. To address this limitation, the efficacy inputs for HSCT survival were based on published literature with comparable patient populations and more mature data.33 In addition, the base case assumed that the efficacy outcomes following HSCT were independent of the initial treatment prior to HSCT. Sensitivity analyses were conducted and confirmed the robustness of the base-case model’s results; however, the impact of these inputs on the study results should be further assessed when long-term ADMIRAL trial data or other relevant data become available.

Finally, the current study compared gilteritinib with SC and BSC. With the availability of additional treatment options for R/R FLT3mut+ AML in the future, BSC will become less relevant. Future studies would be required to address this evidence gap.

Conclusions

Gilteritinib has the potential to bring substantial clinical benefits to patients with R/R FLT3mut+ AML, such as significantly prolonged OS, more sustained clinical remission, and higher likelihood of subsequent HSCT compared with alternative treatment pathways. With ICERs of $115,192/QALY relative to SC and $107,435/QALY relative to BSC, gilteritinib was found to be a cost-effective treatment for R/R FLT3mut+ AML from a US third-party payer’s perspective, based on the commonly used WTP threshold in the United States. Future studies should be conducted to confirm the validity of the current model as well as to integrate more mature data and other therapies as they emerge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing assistance was provided by Richard Xie, Muhan Yuan, and Shelley Batts, employees of Analysis Group, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Döhner H, Weisdorf DJ, Bloomfield CD. Acute myeloid leukemia. New Engl J Med. 2015;373(12):1136-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dores GM, Devesa SS, Curtis RE, Linet MS, Morton LM. Acute leukemia incidence and patient survival among children and adults in the United States, 2001-2007. Blood. 2012;119(1):34-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daver N, Schlenk RF, Russell NH, Levis MJ. Targeting FLT3 mutations in AML: review of current knowledge and evidence. Leukemia. 2019;33(2):299-312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levis M, Small D. FLT3: It does matter in leukemia. Leukemia. 2003;17(9):1738-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shander A, Ozawa S, Hofmann A. Activity-based costs of plasma transfusions in medical and surgical inpatients at a US hospital. Vox Sang. 2016;111(1):55-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ritchie E, Cella D, Fabbiano F, et al. The relationship between transfusion status and patient-reported outcomes in patients with FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia: results from the phase 3 ADMIRAL study. Poster presented at: European School of Hematology; October 24-26, 2019; Estoril, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffin JD, Yang H, Song Y, Kinrich D, Shah MV, Bui CN. Treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization in patients with FLT3-mutated and wild-type acute myeloid leukemia: a medical chart study. Eur J Haematol. 2019;102(4):341-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos N, Mo C, Karp J, Hourigan C. Current approaches in the treatment of relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Med. 2015;4(4):665-695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangan JK, Luger SM. Salvage therapy for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Ther Adv Hematol. 2011;2(2):73-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J, Lv TT, Zhou XF, Huang Y, Liu DD, Yuan GL. Efficacy of common salvage chemotherapy regimens in patients with refractory or relapsed acute myeloid leukemia: a retrospective cohort study. Medicine. 2018;97(39):e12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeidan AM, Gilligan A, Gautam S, Hu N, Grinblatt DL, Pandya BJ. Streamline-study of relapse or refractory (R/R) FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) using electronic medical records (EMR): first analysis from a multicenter, retrospective cohort study. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):5082. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma E, Bonthapally V, Chawla A, et al. An evaluation of treatment patterns and outcomes in elderly patients newly diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia: a retrospective analysis of electronic medical records from US community oncology practices. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16(11):625-636.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee LY, Hernandez D, Rajkhowa T, et al. Preclinical studies of gilteritinib, a next-generation FLT3 inhibitor. Blood. 2017;129(2):257-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori M, Kaneko N, Ueno Y, et al. Gilteritinib, a FLT3/AXL inhibitor, shows antileukemic activity in mouse models of FLT3 mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Invest New Drugs. 2017;35(5):556-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park IK, Mishra A, Chandler J, Whitman SP, Marcucci G, Caligiuri MA. Inhibition of the receptor tyrosine kinase Axl impedes activation of the FLT3 internal tandem duplication in human acute myeloid leukemia: implications for Axl as a potential therapeutic target. Blood. 2013;121(11):2064-2073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. New Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1728-1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cella D, Ritchie EK, Fabbiano F, et al. The relationship between transplant status and patient-reported outcomes in patients with FLT3-mutated relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML): results from the phase 3 ADMIRAL study. Blood. 2019;134 (Suppl 1):3850. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie EK, Cella D, Fabbiano F, et al. The relationship between hospitalization and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in patients with FLT3-mutated (FLT3mut+) relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML): results from the phase 3 ADMIRAL study. Blood. 2019;134 (Suppl 1):1332. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeidan AM, Qi CZ, Pandya BJ, Garnham A, Yang H, Shah MV. Cost-effectiveness analysis of gilteritinib versus salvage chemotherapy (SC) for the treatment of relapsed or refractory (R/R) FLT3-mutated (FLT3mut+) acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1): 3859. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandya B, Yang H, Schmeichel C, Qi CZ, Shah MV. Budget impact associated with the introduction of gilteritinib for the treatment of relapsed or refractory FLT3mut+ acute myeloid leukemia. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(10-a Suppl):S37. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Midostaurin for untreated acute myeloid leukaemia. Technology appraisal guidance [TA523]. 2018. Accessed August 8, 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta523/history

- 22.Bejanyan N, Weisdorf DJ, Logan BR, et al. Survival of patients with acute myeloid leukemia relapsing after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation: a center for international blood and marrow transplant research study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21(3):454-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oran B, Cortes J, Beitinjaneh A, et al. Allogeneic transplantation in first remission improves outcomes irrespective of FLT3-ITD allelic ratio in FLT3-ITD-positive acute myelogenous leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(7):1218-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Othus M, Garcia-Manero G, Godwin J, et al. Associations between complete remissions (CRs) with 7+3 induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia and 2-3 year survival (“potential cure") over the past four decades: Analysis of SWOG trial data. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1): 1301. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimoni A, Labopin M, Savani B, et al. Long-term survival and late events after allogeneic stem cell transplantation from HLA-matched siblings for acute myeloid leukemia with myeloablative compared to reduced-intensity conditioning: a report on behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party of European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9(1):118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takahashi K, Kantarjian H, Pemmaraju N, et al. Salvage therapy using FLT3 inhibitors may improve long-term outcome of relapsed or refractory AML in patients with FLT3-ITD. Br J Haematol. 2013;161(5):659-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ustun C, Giannotti F, Zhang M-J, et al. Outcomes of UCB transplantation are comparable in FLT3+ AML: results of CIBMTR, EUROCORD and EBMT collaborative analysis. Leukemia. 2017;31(6):1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poiré X, Labopin M, Polge E, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation benefits for patients ≥ 60 years with acute myeloid leukemia and FLT3 internal tandem duplication: a study from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2018;103(2):256-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilleece MH, Labopin M, Savani BN, et al. Allogeneic haemopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukaemia in second complete remission: a registry report by the Acute Leukaemia Working Party of the EBMT. Leukemia. 2020;34(1):87-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dillon R, Hills RK, Freeman SD, et al. Molecular MRD status and outcome after transplantation in NPM1 mutated AML: results from the UK NCRI AML17 study. Blood. 2020;135(9):680-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gorcea CM, Burthem J, Tholouli E. ASP2215 in the treatment of relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3 mutation: background and design of the ADMIRAL trial. Future Oncol. 2018;14(20):1995-2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarkozy C, Gardin C, Gachard N, et al. Outcome of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse. Am J Hematol. 2013;88(9):758-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evers G, Beelen DW, Braess J, et al. Outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) beyond first complete remission (CR1). Blood. 2018;132(Suppl 1):4649. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xuan L, Liu Q. Maintenance therapy in acute myeloid leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bazarbachi A, Bug G, Baron F, et al. Clinical practice recommendation on hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia patients with FLT3-internal tandem duplication: a position statement from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2020;105(6):1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee CJ, Savani BN, Mohty M, et al. Post-remission strategies for the prevention of relapse following allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia: expert review from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54(4):519-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Position statement on use of the EQ-5D-5L value set for England. 2019. Accessed April 29, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/technology-appraisal-guidance/eq-5d-5l

- 38.Janssen B, Szende A. Population norms for the EQ-5D. In: Janssen B, Szende A, Cabases J, eds. Self-reported Population Health: An International Perspective Based on EQ-5D. Springer; 2014:19-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swinburn P, Lloyd A, Nathan P, Choueiri TK, Cella D, Neary MP. Elicitation of health state utilities in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(5):1091-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doyle S, Lloyd A, Walker M. Health state utility scores in advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;62(3):374-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lloyd A, Nafees B, Narewska J, Dewilde S, Watkins J. Health state utilities for metastatic breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(6):683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nafees B, Stafford M, Gavriel S, Bhalla S, Watkins J. Health state utilities for non small cell lung cancer. Health Qual Life Out. 2008;6(1):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joshi N, Hensen M, Patel S, Xu W, Lasch K, Stolk E. Health state utilities for acute myeloid leukaemia: a time trade-off study. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(1):85-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.IBM. Micromedex. RED BOOK online. Database. 2020. Accessed January 30, 2020. https://www.ibm.com/us-en/marketplace/micromedex-red-book

- 45.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician fee schedule. 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/2020-physician-fee-schedule-guide.pdf

- 46.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare cost and utilization project. 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020. https://www.hcupnet.ahrq.gov [PubMed]

- 47.Kawatkar AA, Farias AJ, Chao C, et al. Hospitalizations, outcomes, and management costs of febrile neutropenia in patients from a managed care population. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(9):2787-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eber MR, Laxminarayan R, Perencevich EN, Malani A. Clinical and economic outcomes attributable to health care–associated sepsis and pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):347-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paoli CJ, Reynolds MA, Sinha M, Gitlin M, Crouser E. Epidemiology and costs of sepsis in the United States—an analysis based on timing of diagnosis and severity level. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(12):1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagiwara M, Sharma A, Chung KC, Delea TE. Healthcare resource utilization and costs in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Med Econ. 2018;21(11):1119-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Overview of the ICER value assessment framework and update for 2017-2019. 2017. Accessed August 26, 2021. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICER-value-assessment-framework-Updated-050818.pdf

- 52.Bell JA, Galaznik A, Farrelly E, et al. Economic burden of elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated in routine clinical care in the United States. Leuk Res. 2018;71:27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Institute for Clinical and Econoimc Review. 2020-2023 value assessment framework. 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ICER_2020_2023_VAF_013120-4.pdf

- 54.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Interim process and methods of the highly specialised technologies programme. Updated to reflect 2017 changes. 2017. Accessed February 1, 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/About/what-we-do/NICE-guidance/NICE-highly-specialised-technologies-guidance/HST-interim-methods-process-guide-may-17.pdf [PubMed]

- 55.Stein E, Xie J, Duchesneau E, et al. Cost effectiveness of midostaurin in the treatment of newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;37(2):239-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Batty N, Wiles S, Kabalan M, et al. Decitabine is more cost effective than standard conventional induction therapy in elderly acute myeloid leukemia patients. Blood. 2013;122(21):2699. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kansal A, Du M, Herrera-Restrepo O, et al. Cost-effectiveness of CPX-351 versus 7+3 regimen in the treatment of treatment-related acute myeloid leukemia (tAML) or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (MRC). Blood. 2017;130 (Suppl 1):4674. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang R, Janssen MFB, Pickard AS. US population norms for the EQ-5D-5L and comparison of norms from face-to-face and online samples. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):803-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Swinburn P, Lloyd A, Nathan P, Choueiri TK, Cella D, Neary MP. Elicitation of health state utilities in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(5):1091-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dasta JF, McLaughlin TP, Mody SH, Piech CT. Daily cost of an intensive care unit day: the contribution of mechanical ventilation. Criti Care Med. 2005;33(6):1266-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Medeiros BC, Pandya BJ, Chen C-C, et al. Economic burden of treatment episodes in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients in the US: a retrospective analysis of a commercial payer database. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):4694. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tremblay G, Dolph M, Patel S, Brandt P, Forsythe A. Cost-effectiveness analysis for midostaurin versus standard of care in acute myeloid leukemia in the United Kingdom. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2018;16:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare provider utilization and payment data: inpatient (MS-DRG 014). 2016. Accessed February 22, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Inpatient

- 64.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical laboratory fee schedule. 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ClinicalLabFeeSched/Clinical-Laboratory-Fee-Schedule-Files

- 65.Olszewski AJ, Egan PC, LeBlanc TW. Transfusion dependence and use of hospice among Medicare beneficiaries with leukemia. Blood. 2017;130(Suppl 1):277. [Google Scholar]