Abstract

Purpose:

To analyze the visual outcome and complications of Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) with their management in 256 eyes at a tertiary eye care center in southern India.

Methods:

This is a retrospective interventional study of 62 months duration conducted at a tertiary eye care center in southern India. Two hundred and fifty-six eyes of 205 patients were included in the study after obtaining written informed consent from the patients. All cases of DSEK were performed by a single experienced surgeon. In all cases, donor dissection was performed manually. A Sheet’s glide was inserted through the temporal corneal incision and donor button was placed on the Sheet’s glide with the endothelial side down. The lenticule was separated and inserted into the anterior chamber by pushing the lenticule into the anterior chamber using Sinskey’s hook. Any complication, either intraoperative or postoperative, was recorded and managed either medically or by appropriate surgical means.

Results:

The mean best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) before surgery was CF-1 m, which improved to 6/18 after surgery. Intraoperative donor graft perforation during dissection was seen in 12 cases, thin lenticule in three eyes, and repeated artificial Anterior Chamber (AC) collapse in three eyes. Dislocation of lenticule was the most common complication seen in 21 eyes, which was managed by graft repositioning and rebubbling. Eleven cases had minimal separation of the graft and seven cases had interface haze. Pupillary block glaucoma was seen in two cases that resolved with partial release of bubble. Surface infiltrate was seen in two cases, which was managed with topical antimicrobial agents. Primary graft failure was seen in two cases.

Conclusion:

DSEK is a promising alternative to penetrating keratoplasty for corneal endothelial decompensation, but it also has its own merits and limitations, and most often, merits overweigh limitations.

Keywords: DSEK, endothelial keratoplasty, Fuch’s endothelial corneal dystrophy

Endothelial keratoplasty is the recent modality of choice in patients with corneal endothelial dysfunction, as it provides rapid visual rehabilitation and the results are also great in terms of safety and efficacy.[1] Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) refinements with smaller incisions and thinner grafts have produced very favorable efficacy and safety profiles that have significantly lowered the threshold for treatment. Even though DSEK appears similar to Penetrating Keratoplasty (PKP) in terms of graft clarity, it is superior to PKP in many aspects like faster visual recovery, less astigmatism, no suture related surface problems and maintenance of the tectonic strength of the globe. Patients’ vision improves dramatically after 4–6 weeks of surgery compared to months to years after PKP.[2]

The most widely performed and reported form of Endothelial Keratoplasty (EK) surgery today is DSEK. The procedure involves scoring the diseased host endothelium and Descemet’s membrane with special instruments through a corneal incision and insertion of donor endothelial lenticule either prepared in the operation theater by the operating surgeon him/herself or the precut DSEK tissue received from the eye bank is used.

Graft detachment is the most common postoperative complication, but repositioning of graft is an effective means for its reattachment. Descemet membrane tags and use of blunt dissector for dissection or presence of viscoelastic remnants is the cause of graft interface haze and lenticule displacement. Other complications found in this study were graft failure, pupillary block glaucoma, and surface infiltrates.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the visual outcome and to analyze the peroperative and postoperative complications of DSEK with their possible management.

Methods

Ethical committee approval was obtained, and the study adhered to the tenets of Declaration of Helsinki.

The study was conducted as a retrospective interventional study of 62 (range: 6–62 months, average 16.8 months) months duration at a tertiary health care center in southern India. Two hundred and fifty-six eyes of 205 patients were included in the study after obtaining written informed consent from the patients. All cases of DSEK were performed by a single experienced surgeon. Inclusion criteria were patients 18–65 years of age, presenting with decreased visual acuity and diagnosed to have corneal pathology secondary to endothelial dysfunction. Exclusion criteria were patients with debilitating illness precluding detailed ophthalmic examination and patients not willing to give a written informed consent. Preoperative data collected included age, sex, visual acuity, ocular examination, surgical history, and anterior segment optical coherence tomography.

Postoperatively, type of procedure, visual acuity, complications, intraocular pressure (IOP) estimated using pneumotonometry, and duration of follow-up were noted.

Surgical procedure: Before the surgery, patients received a peribulbar block. The donor corneoscleral tissue was placed on an artificial anterior chamber. A lamellar dissection was carried out at a depth of around 300 or 400 mm and a donor posterior cornea (endothelium, Descemet’s membrane, and a portion of posterior stroma) was created by manual dissection. The intended depth of manual dissection was 300 mmi in most cases, but in case of thick and edematous cornea, 400 mm guarded blade was used for dissection. The average lenticule thickness was 80–150 mm. After the donor tissue was prepared, it was trephinated to a desired diameter and separated from the anterior lamellae. The host cornea was then marked with a blunt trephine of desired diameter. Two 1-mm paracenteses tracts were made at the limbus and high-molecular-weight viscoelastic substance was injected into the anterior chamber. A 3–3.5 mm temporal corneal incision was made at the limbus. Using a reverse Sinskey’s hook, the Descemet’s membrane and the endothelium were scored in a circular fashion and then stripped off with an endothelial stripper. The viscoelastic was removed from the anterior chamber using the irrigation/aspiration unit. A Sheet’s glide was inserted through the temporal incision and visco was injected at the wound and on the surface of the Sheet’s glide. Donor button was placed on the Sheet’s glide with the endothelial side down and lenticule was inserted into the anterior chamber by pushing the lenticule into the anterior chamber using Sinskey’s hook. The graft was unfolded and balanced salt solution was used to form the anterior chamber and to wash off the viscoelastic substance. The temporal wound was sutured with 10-0 nylon suture in a “figure of 8” manner. The tissue was positioned and centered with respect to the pupil within the anterior chamber, and the anterior chamber was completely filled with air to force the apposition of the graft to the recipient stromal bed. The patient was then instructed to lie in the face-up position until the following day. Postoperatively, all patients were started on topical antibiotics (0.5% moxifloxacin) four times/day for 2 weeks and topical steroids (1% prednisolone) six times/day for the first week and then tapered gradually over 3 months and maintained on a minimal dose until 1 year post-op. Preservative-free tear substitute (0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose) was given for 12 weeks. The patients were followed at day 1, 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 6 months initially after the surgery, then every 6 months thereafter. All the complications during and after surgery were noted during the follow-up period and appropriate corrective measures were taken to address the complications.

Results

Two hundred and fifty-six eyes of 205 patients underwent DSEK, of which 154 cases were unilateral and 51 cases were bilateral. Ninety-eight patients were males and 107 were females. The median age of these patients was 59.5 years (range: 18–65 years). The follow-up period ranged from 6 to 62 months, with an average of 16.8 months. Table 1 shows the indications for DSEK in our study. Demographic data, number of patients, and the follow-up period are shown in Table 2. Two patients lost to follow-up after 5 months of the procedure. Pseudophakic bullous keratopathy (PBK) was the most common indication for DSEK in our study and it was done in 175 (68.35%) eyes. One hundred and sixty-nine (66.01%) eyes had posterior chamber intraocular lens (PCIOL) and six (2.34%) eyes had anterior chamber intraocular lens (ACIOL). ACIOL was explanted and replaced with iris claw lens during the procedure. Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy with different grades of cataract was present in 27 (10.54%) eyes and aphakic bullous keratopathy in 19 (7.42%) eyes. Post-PKP failed graft was present in 22 (8.59%) eyes and failed DSEK (repeat DSEK) in 13 (5.07%) eyes.

Table 1.

Indications of DSEK in our study

| Indications | Number of eyes |

|---|---|

| Pseudophakic bullous keratopathy | 175 (68.35%) |

| Fuch’s endothelial dystrophy | 27 (10.54%) |

| Aphakic bullous keratopathy | 19 (7.42%) |

| Failed DSEK | 13 (5.07%) |

| Rejected PK | 22 (8.59%) |

DSEK=Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty

Table 2.

Demographic data of the study subjects and their follow-up period

| Demographic Data | Number of Patients with Mean Age and Duration Of Study |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 205 |

| Total number of cases | 256 |

| Unilateral: bilateral | 154:51 |

| Male: female | 98:107 |

| Mean age | 59.5 years (range: 18-65 years) |

| Mean follow-up period | 18±9.2 months (6 months to 6 years) |

The preoperative donor endothelial cell density (ECD) was 2442–3108 cells/mm2 (median: 2667 cells/mm2), and donor age was between 12 and 52 years (average = 38 years).

Operative complications: Intraoperatively, 12 (4.68%) eyes had Descemet’s membrane perforation during donor lamellar dissection; hence, the dissection was started and completed in other locations in eight (3.12%) cases. Repeated artificial anterior chamber collapse was noted in four (1.56%) cases, which led to thin donor lenticule in three (1.17%) cases. Thin graft was not intended, but it happened because of repeated anterior chamber collapse secondary to technical issues and leakage. There were no folds in the lenticule and the results were good.

Postoperative complications: The most common complication in early postoperative period was donor dislocation. Dislocation was noted in 21 (8.20%) eyes after the surgery, and minimal separation of the graft without dislocation was seen in 11 (4.29%) cases. Primary graft failure (PGF) was noted in two (0.78%) cases. Immediate postoperative glaucoma 1 day after the surgery was seen in two (0.78%) eyes. Pupillary block secondary to air bubble was the main cause for post-op rise in IOP. Two (0.78%) patients developed raised IOP after chronic steroid usage. Visually significant interface haze was seen in seven (2.73%) cases after DSEK surgery. Two (0.78%) patients developed haze because of retained Descemet’s tags and one (0.39%) due to irregular dissection caused by usage of blunt dissector. Three cases (1.17%) who underwent DSEK for corneal failure secondary to Toxic Anterior Segment Syndrome (TASS) developed postoperative haze and were managed with higher dose of steroids, but the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was less than 6/60 in two cases. Retained viscoelastic in the interface was seen in one (0.39%) eye. Surface infiltrates were seen in two (0.78%) eyes post-DSEK surgery. Table 3 shows a list of all the complications with their respective percentage.

Table 3.

List of all the complications with their respective percentage

| Complications | Number of Eyes |

|---|---|

| Descemet’s perforation of the donor cornea | 12 cases (4.68%) |

| Thin donor lenticule | Three eyes (1.17%) |

| Donor dislocation | 21 eyes (8.20%) |

| Partial donor nonattachment | 11 eyes (4.29%) |

| Air-induced pupillary block glaucoma | Two eyes (0.78%) |

| Steroid-induced glaucoma | Two eyes (0.78%) |

| Primary graft failure | Two eyes (0.78%) |

| Interface haze due to retained Descemet’s tag | Two eyes (0.78%) |

| Interface haze due to irregular dissection by blunt dissector | One eye (0.39%) |

| Interface haze in patients with toxic anterior segment syndrome | Three eyes (1.17%) |

| Surface infiltrates | Two eyes (0.78%) |

| Graft rejection | Seven eyes (2.73%) |

The BCVA postoperatively was 6/6 in 38 eyes (14.84%), 6/18–6/6 p in 150 eyes (58.59%), 6/60–6/24 in 55 eyes (21.48%), and less than 6/60 in 11 (4.29%) eyes. BCVA less than 6/60 was because of graft rejection in seven eyes, graft failure in two eyes, and interface haze in two eyes.

The specular count was 1002–2451 cells/mm2 (median: 2217) in 220 patients after 6 months, 798–2280 cells/mm2 (median: 1980) in 176 patients after 1 year, and 706–1950 cells/mm2 (median: 1620) in 32 patients after 2 years.

Discussion

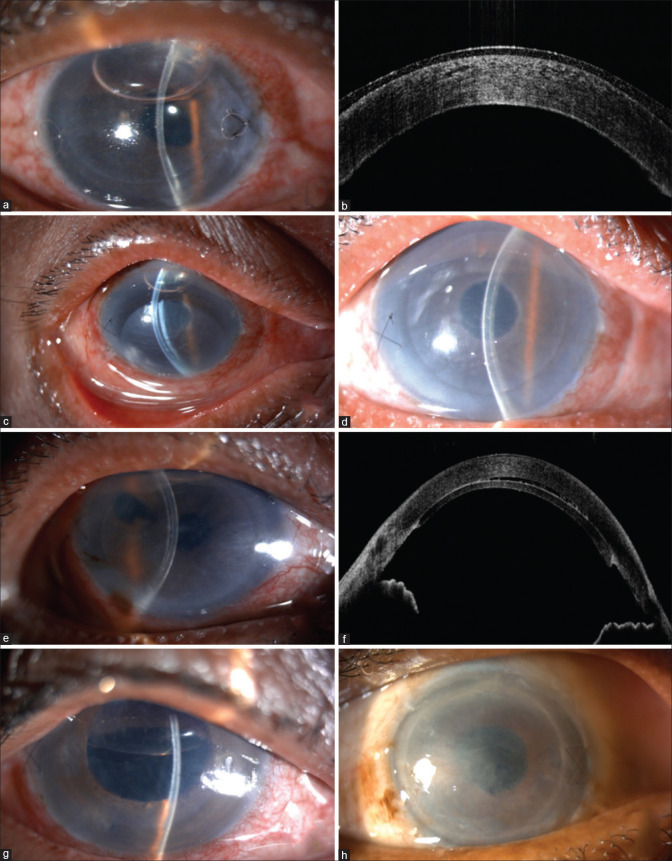

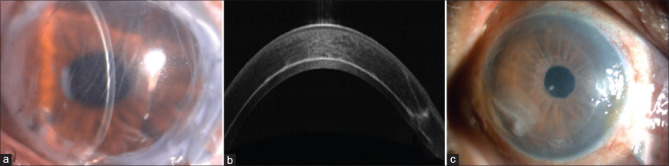

DSEK has been performed for endothelial disease by experienced surgeons as it demands special skills with a longer learning curve. Over the period of time, DSEK has evolved for the benefit of surgeons and also to reduce the intraoperative complications associated with the conventional penetrating keratoplasty. However, multiple complications are reported intraoperatively and postoperatively in DSEK and various measures are adopted to overcome these complications. Here, in this article, we analyzed various complications that occurred during various stages of surgery and post-surgery. Fig. 1 shows the early postoperative complications and Fig. 2 shows the late postoperative complications in our study.

Figure 1.

(a) Slit-lamp image showing thin lenticule. (b) Anterior segment optical coherence tomography picture of thin lenticule. (c) Donor dislocation. (d) Postoperative picture of the same patient after repositioning and rebubbling. (e) Minimal lenticule separation. (f) Anterior segment optical coherence tomography showing minimal lenticule separation. (g) Air-induced pupillary block. (h) Primary graft failure

Figure 2.

(a) Slit-lamp image showing interface haze. (b) Anterior segment optical coherence tomography picture of the same patient showing interface haze. (c) Slit-lamp image showing surface infiltrates

Descemet’s membrane perforation: Descemet’s membrane perforation of the donor cornea can occur during donor dissection. Intraoperatively, 12 (4.68%) eyes had Descemet’s membrane perforation during donor dissection, but it did not result in need to use additional donor tissue and dissection was started and completed in other location in 8 (3.12%) cases, while in remaining 4 cases Descemet perforation was seen towards the end of the dissection. Artificial anterior chamber collapse secondary to leakage could be the reason for this. A study conducted by Basak S. on complications and management in DSEK in 430 cases showed intraoperative Descemet’s perforation of the donor cornea in 1 eye (0.2%). Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) is better than manual dissection as chances of perforation and interface haze are less and postoperative BCVA is better.

Posterior graft dislocation

A dislocation represents lack of adherence of the donor posterior lenticule to the recipient stroma, and it is typically evident within the initial week, although late dislocations may also occur. Dislocations may represent either fluid in the interface of an otherwise well-positioned graft or complete dislocation into the anterior chamber.[4] In our study, dislocation was noted in 21 eyes after the surgery and minimal separation without dislocation of the graft was seen in 11 cases. Repositioning of the lenticule along with rebubbling was done, and successful reattachment occurred in all 21 cases. In 11 eyes with minimal separation of the lenticule, repositioning and rebubbling was done and venting incisions were given in paracentral positions. Dislocation rates may vary from 0% to 82%, with an average dislocation rate of 14.5%. The potential cause of donor dislocation may be retained high-molecular-weight viscoelastic that was used during Descemet scoring, insufficient air in the AC, or patient squeezing. Hypotony could be the reason for donor dislocation in patients with aphakic bullous keratopathy. A study conducted by Price and Price[5] showed donor detachment in 6% of the patients and reattachment was done by injecting an air bubble to press the donor against the recipient cornea. It has been seen in various studies that the incidence of graft dislocation is reduced with experience and time.[6,7] Spontaneous resolution may also take place in some patients.

Primary graft failure

Corneal grafts that have not cleared after 2 months of surgery are classified as PGFs. PGF was noted in two cases in our study. Poor quality tissue and poor surgical technique have been linked to PGF in DSEK, with surgeon inexperience and related excessive iatrogenic intraoperative donor endothelial trauma being the main factors. In our study, repeat DSEK was done in both the cases and patients were doing well. Recent reports have suggested that increased donor endothelial cell loss occurs during donor lamellar dissection and donor unfolding in the anterior chamber.[5] PGF is the third most common reported complication following DSEK and this is supported by recent reports of higher endothelial cell loss at 6 months and 1 year after DSEK compared to PK, which is related to more donor tissue manipulation in DSEK.[7]

Glaucoma: Four cases developed glaucoma after DSEK surgery. Immediate postoperative glaucoma 1 day after the surgery was seen in two eyes. Pupillary block secondary to air bubble was the main cause for the post-op rise in IOP. Two patients developed raised IOP after chronic steroid usage.

Raised IOP is the most significant risk factor following DSEK that can lead to glaucoma. This can result in poor post-op outcome due to its difficult diagnosis, complexity of management, and the risk of graft failure.[8] There are a few proposed causes of increased IOP after DSEK, including the use of topical steroids, retained viscoelastic, inflammation, peripheral anterior synechiae, iatrogenic damage to trabecular meshwork, and distortion of the angle.[9] A study conducted by Holzer et al.[10] showed a direct association between increased viscoelastic substance’s viscosity and increased IOP, but there was no statistical significance. A study conducted by Elalfy et al.[11] showed that all eyes with steroid-induced IOP elevation were on the highest potency of steroid drop, dexamethasone 0.1%, and the earliest onset of IOP elevation was seen within a week. Steroid-induced IOP elevation could normally be controlled by tapering steroids, changing steroids, or starting antiglaucoma medication. Air in the AC can lead to pupillary block, while air that has intruded posterior to the iris may cause forward iris rotation and angle closure. In our study, pupillary block glaucoma was seen in two cases that resolved with burping of bubble. IOP may spike from pupil block when sitting in an upright position. This can be prevented by creating an inferior peripheral iridectomy, rather than one in the 12 o’clock position.[12]

Interface haze: Interface haze was seen in seven cases after DSEK surgery. Two patients developed haze because of retained Descemet’s tags and one due to irregular dissection caused by usage of blunt dissector. The haze was present in the periphery and was managed with routine postoperative steroid drops. TASS was the indication for DSEK in three eyes which developed interface haze and retained viscoelastic in the interface was seen in one eye. A study conducted by Anshu et al.[13] showed clearing of the haze and attainment of BCVA of 20/40 or better in three out of five patients without any intervention. Two patients with more extensive interface haze were managed with irrigation and aspiration of the graft–host interface, with quick resolution of the haze.[13]

Graft infiltrates: Surface infiltrates were seen in two eyes post-DSEK surgery. In one patient, infiltrates were present in the mid-periphery and in the other patient, infiltrates were present in the periphery. In the second patient, there was peripheral extension of descemetorhexis intraoperatively that led to decompensated cornea in the periphery and ruptured bullae with secondary infiltrates. For both the patients, corneal scraping was done and samples were sent for microbiological examination. Antibiotics were started. After the ulcer was healed, anterior stromal puncture with focal amniotic membrane grafting was done in the periphery to prevent recurrent bullae formation. Bullous keratopathy secondary to graft failure, following any type of keratoplasty, serves as another important risk factor for graft infiltrates. The most common fungi associated with EK are from the Candida species, with the majority caused by either Candida albicans or Candida parapsilosis.[14] In cases of DSEK, removal of donor lenticule may lead to intraocular spread of infection resulting in endophthalmitis. A repeat DSEK can be considered once complete resolution of infection is achieved and if the host cornea is clear.[15]

Graft rejection: Seven eyes had endothelial graft rejection that occurred between 7 and 12 months after DSEK. One patient with graft rejection presented with sudden dimness of vision and was treated with intravenous methyl prednisolone. In other patients, rejection was diagnosed during routine examination and all eyes had anterior chamber cells, keratic precipitates, and corneal edema. Topical prednisolone was started in all the patients. The rejection episode was reversed in one patient with medication, but in rest of the eyes, graft edema persisted and re-DSEK was eventually required. Jordan et al.[16] reported endothelial rejection in 54 out of 598 eyes (9.03%); similar to our study, rejection line was not noted in any of the cases.

Table 4 shows a comparison of the incidence of complications in other studies with our study.

Table 4.

Comparison of DSEK complications reported in other studies with those of our study

| Author | No. of eyes | Follow-up period | Descemet membrane perforation | Thin donor lenticule | Donor dislocation Total Partial | Primary graft failure | Interface haze | Raised IOP | Surface infiltrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our study | 256 | 18 months (6 months to 6 years) | 12 | 3 | 21 11 | 2 | 7 | 2- Air induced 2- Steroid induced | 2 |

| Basak and Basak[3] | 430 | 3-60 months (mean 18.7 months) | 1 | 8 | 21 3 | 2 | 2 | 12- Air induced 7- Secondary glaucoma | 1 |

| Price and Price[5] | 200 | 7-20 months | 12 | 7 | 2 | ||||

| Shah et al.[17] | 21 | 2-39 months | 1 2 | 2 | 3 | ||||

| Suh et al.[18] | 118 | 27 | 21 | ||||||

| Daubert et al.[19] | 57 | 16.4±15.6 months | 12 | 3 | 9 | ||||

| Mitry et al.[20] | 246 | 6-30 months (mean 17 months) | 19 | 41 |

DSEK=Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty, IOP=intraocular pressure

Similar complications of DSEK have been reported in various other studies. Shah et al.[17] reported that pupillary block glaucoma was seen in three eyes and donor tissue dislocation in two eyes among 51 cases in their follow-up period of 2 years. Suh et al.[18] reported that graft detachment was the most common type of complication encountered in 27 (23%) of 118 eyes, but postoperative repositioning or rebubbling allowed for graft reattachment in most cases. Several other authors have shown that donor dislocation is the most common complication seen in DSEK and with experience and time, the dislocation rate is reduced.[19,20] Cystoid macular edema and retinal detachment were not seen in any of the postoperative cases.

Conclusion

DSEK is a promising alternative to penetrating keratoplasty for corneal endothelial decompensation. If the surgery is done carefully, it can reduce the complications. These complications can occur at any stage of surgery; however, if identified early and managed adequately, it can result in optimal outcome.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Wu EI, Ritterband DC, Yu G, Shields RA, Seedor JA. Graft rejection following descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty:Features, risk factors, and outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153:949–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WB, Mannis MJ. Corneal suturing techniques. In: Macsai MS, editor. Ophthalmic Microsurgical Suturing Techniques. Berlin: Springer; 2007. pp. 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basak SK, Basak S. Complications and management in Descemet's stripping endothelial keratoplasty:Analysis of consecutive 430 cases. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62:209–18. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.116484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee WB, Jacobs DS, Musch DC, Kaufman SC, Reinhart WJ, Shtein RM. Descemet's stripping endothelial keratoplasty:Safety and outcomes:A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1818–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price FW, Jr, Price MO. Descemet's stripping with endothelial keratoplasty in 200 eyes:Early challenges and techniques to enhance donor adherence. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32:411–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.12.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terry MA, Hoar KL, Wall J, Ousley P. Histology of dislocations in endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK and DLEK):A laboratory-based, surgical solution to dislocation in 100 consecutive DSEK cases. Cornea. 2006;25:926–32. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000243958.07027.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mearza AA, Qureshi MA, Rostron CK. Experience and 12-month results of Descemet-stripping endothelial keratoplasty (DSEK) with a small-incision technique. Cornea. 2007;26:279–83. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31802cd8c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdurmus M, Cohen EJ, Yildiz EH, Hammersmith KM, Laibson PR, Varssano D, et al. Steroid-induced intraocular pressure elevation or glaucoma after penetrating keratoplasty in patients with keratoconus or Fuchs dystrophy. Cornea. 2009;28:759–64. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181967318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber KK, Maier AK, Klamann MK, Rottler J, Özlügedik S, Rosenbaum K, et al. Glaucoma in penetrating keratoplasty:Risk factors, management and outcome. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;251:105–16. doi: 10.1007/s00417-012-2065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holzer MP, Tetz MR, Auffarth GU, Welt R, Völcker HE. “Effect of healon5 and 4 other viscoelastic substances on intraocular pressure and endothelium after cataract surgery.”. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:213–8. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elalfy M, Maqsood S, Soliman S, Hegazy SM, Hannon AA, Gatzioufas Z, et al. Incidence and risk factors of ocular hypertension/glaucoma after descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:2179–88. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S299098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Röck D, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Röck T, Yoeruek E. “Air bubble–induced high intraocular pressure after descemet membrane endothelial keratoplasty.”. Cornea. 2016;35:1035–9. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anshu A, Planchard B, Price MO, da R Pereira C, Price FW., Jr A cause of reticular interface haze and its management after descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2012;31:1365–8. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823d027d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin IH, Chang YS, Tseng SH, Huang YH. A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the clinical and microbiological profiles of post-penetrating keratoplasty keratitis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32751. doi: 10.1038/srep32751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiura TL, Ritterband DC, Koplin RS, Shih C, Palmiero PM, Seedor JA. Endophthalmitis after descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty with concave-oriented dislocation on slit-lamp optical coherence topography. Cornea. 2010;29:222–4. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181a325c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jordan CS, Price MO, Trespalacios R, Price FW., Jr Graft rejection episodes after Descemet stripping with endothelial keratoplasty:Part one:Clinical signs and symptoms. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:387–90. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.140020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah Z, Hussain I, Sethi S, Khan BS, Khan T. Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK) Pak J Ophthalmol. 2020;36 doi:10.36351/pjo.v36i2.977. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suh LH, Yoo SH, Deobhakta A, Donaldson KE, Alfonso EC, Culbertson WW, et al. Complications of Descemet's stripping with automated endothelial keratoplasty:Survey of 118 Eyes at one institute. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daubert J, O'Brien TP, Adler E, Spierer O. Outcomes of complex Descemet stripping endothelial keratoplasty performed by cornea fellows. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18:281. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0946-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitry D, Bhogal M, Patel AK, Lee BS, Chai SM, Price MO, et al. Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty after failed penetrating keratoplasty:Survival, rejection risk, and visual outcome. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:742–9. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]