Abstract

The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen EBNA1 is the only viral protein detectably expressed in virus genome-positive Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL); recent work has suggested that viral strains with particular EBNA1 sequence changes are preferentially associated with this tumor and that, within a patient, the tumor-associated variant may have arisen de novo as a rare mutant of the dominant preexisting EBV strain (K. Bhatia, A. Raj, M. J. Gutierrez, J. G. Judde, G. Spangler, H. Venkatesh, and I. T. Magrath, Oncogene 13:177–181, 1996). In the present work we first study 12 BL patients and show that the virus strain in the tumor is identical in EBNA1 sequence and that it is matched at several other polymorphic loci to the dominant strain rescued in vitro from the patient’s normal circulating B cells. We then analyze BL-associated virus strains from three different geographic areas (East Africa, Europe, and New Guinea) alongside virus isolates from geographically matched control donors by using sequence changes in two separate regions of the EBNA1 gene (N-terminal codons 1 to 60 and C-terminal codons 460 to 510) to identify the EBNA1 subtype of each virus. Different geographic areas displayed different spectra of EBNA1 subtypes, with only limited overlap between them; even type 2 virus strains, which tended to be more homogeneous than their type 1 counterparts, showed geographic differences at the EBNA1 locus. Most importantly, within any one area the EBNA1 subtypes associated with BL were also found to be prevalent in the general population. We therefore find no evidence that Burkitt lymphomagenesis involves a selection for EBV strains with particular EBNA1 sequence changes.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a B-lymphotropic gamma herpesvirus, is widespread in all human populations, where it is carried by the great majority of individuals as a lifelong asymptomatic infection. This same virus has potent B-cell growth transforming ability and is strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of several human malignancies, notably in the endemic and in some sporadic cases of Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL), in some cases of classical Hodgkin’s disease (HD), in a specific type of nasal T-cell lymphoma, and in undifferentiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) (23, 26). How the virus might contribute to the pathogenesis of such a diverse set of malignancies remains to be determined. One hypothesis, however, is that particular EBV strains could be associated with particular tumor types, possibly through a change in cell tropism or through the acquisition of mutations in growth-transforming latent-cycle genes that endow the virus with increased oncogenic potential (1, 7, 8, 16, 17, 19, 20, 22). Interest in this possibility has grown as the extent of EBV’s genetic diversity has become more apparent. In this context there are two major types of EBV, now called types 1 and 2, that are distinguished by linked polymorphisms in the latent-cycle genes encoding the nuclear antigens EBNAs 2, 3A, 3B, and 3C (9, 31). This remains the only genetic classification for which there is a clear biological correlate, in that type 1 strains have stronger in vitro transforming ability for resting B cells than do type 2 strains (27). Within each virus type, however, there are now many polymorphic markers that allow individual strains to be distinguished from one another; some markers are informative among viral strains from the same geographic area (11, 32, 33), whereas others represent differences that largely correlate with the geographical origin of the virus (1, 2, 10, 17, 18, 21, 24).

The present work focuses on the latent-cycle gene encoding the virus genome maintenance protein EBNA1. Though EBNA1 does not display any obvious type-specific polymorphism, a degree of interstrain sequence variation has been noted from the analysis of EBV-associated tumors and of viral strains detectable in the blood and/or throat washings of asymptomatic carriers (4, 14, 35, 38). The EBNA1 protein is composed of unique N-terminal (residues 1 to 89) and C-terminal (residues 328 to 641) domains flanking a large Gly-Ala repeat, and most sequencing studies have focused on a region (residues 466 to 527) which is within the molecule’s DNA binding-dimerization domain (3) and which, from X-ray crystallographic data, contains at least some of the important DNA contact residues (5, 6). Recently, Bhatia and colleagues (4, 14) have used signature changes at residue 487 to classify five distinct EBNA1 subtypes; these were the prototype B95.8 strain sequence P-ala, a closely related subtype P-thr, and three more distant variants V-pro, V-leu, and V-val. These authors reported that in a heterogeneous panel of EBV-positive BLs (24 from endemic and nonendemic areas of Africa and 12 from North and South America), the distribution of EBNA1 subtypes was markedly different from that detectable in the blood and/or throat washings of a similarly heterogeneous panel of healthy controls. In particular, almost 50% of the tumors carried a V-leu subtype sequence, whereas this was never found in controls (4).

The implication, that certain EBNA1 subtypes carried a greater lymphomagenic risk, was particularly interesting because EBNA1 is the only viral protein detectably expressed in BL tumor cells (30). Furthermore, there is circumstantial evidence from transgenic mouse studies (37), from in vitro work with a BL cell line (34), and from transactivation assays with reporter gene constructs (36) to suggest that EBNA1 has other activities besides virus genome maintenance and that these could underpin a more direct role for the protein in BL pathogenesis. We were therefore interested in addressing two outstanding questions raised by these studies. First, might the process of EBV-associated lymphomagenesis involve the de novo generation of a rare pathogenic viral variant by mutation of the patient’s dominant preexisting strain? For that purpose, we study here 12 cases of endemic BL and compare the viral strain within the tumor with that rescued from the patient’s normal B cells. Second, does the difference between BL-associated and control donor-derived EBNA1 subtypes hold true when comparisons are focused within more circumscribed geographic areas? Here we report appropriately controlled studies on BL from two endemic areas, East Africa (Uganda and Kenya) and New Guinea, and on sporadic cases of BL from Europe.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

BL and control samples from East Africa.

A total of 55 endemic BLs from East Africa (44 carrying type 1 EBV and 11 carrying type 2 EBV) were obtained as freshly excised biopsies transported on ice in culture medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 40 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 10% [vol/vol] fetal calf serum) and were received within 48 to 72 h. Of these, 12 (8 type 1 and 4 type 2) came from the Lake Victoria-Machakos regions of Kenya; 9 of these Kenyan tumors were studied as derived cell lines with confirmed BL-associated chromosomal translocations that have been fully described elsewhere (13, 28), and 3 were studied as biopsy cell suspensions. A further 43 BLs (36 type 1 and 7 type 2) came from the West Nile region of Uganda; 27 of these were studied as derived cell lines with confirmed BL-associated chromosomal translocations (13a), and 16 were studied as biopsy cell suspensions. Heparinized blood samples from the same BL patients and from appropriate control donors were transported at ambient temperature in an equal volume of RPMI 1640 medium and were received within 48 to 72 h. In 12 cases of BL (2 from Kenya and 10 from Uganda) the resident EBV strain in the patient’s normal peripheral B cells was rescued by spontaneous outgrowth of blood lymphocyte cultures to EBV-positive lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) as described elsewhere (43); between 1 and 10 independently-derived LCLs were obtained per patient. In addition, a total of 32 control EBV isolates (25 type 1 and 7 type 2) were likewise rescued in vitro from normal individuals resident in the same BL endemic areas. Of these 20 (14 type 1 and 6 type 2) came from Kenyan donors as described elsewhere (43) and 12 (11 type 1 and 1 type 2) came from Ugandan donors.

BL and control samples from Europe.

A total of three EBV-positive sporadic BLs (all carrying type 1 EBV) were available as derived cell lines with confirmed BL-associated chromosomal translocations. These lines, kindly provided by G. Lenoir (IARC, Lyon, France), were derived from French Caucasian individuals and have been described elsewhere (29). A total of 32 control EBV isolates (23 type 1 and 9 type 2) were generated by spontaneous in vitro transformation of peripheral blood B cells from British Caucasian donors. Of these 22 were healthy adults, 2 were infectious mononucleosis patients (prefix IM), 4 were HIV-positive hemophilia patients (prefix QEH, BCH, or OX), and 4 were HIV-positive homosexuals (prefix EBH). Note that many of these control isolates were from earlier studies (39–42), and the panel was deliberately selected so that the numbers of type 2 Caucasian isolates matched those in the East African panels.

BL and control samples from New Guinea.

A total of four cell lines derived from endemic BL (two type 1 EBV and two type 2) and four spontaneously derived LCLs from normal individuals (two type 1 and two type 2) were available for study. These, kindly provided by D. Moss (QIMR, Brisbane, Australia), have been described elsewhere (2, 25, 29) and come from lowland regions of New Guinea where BL is endemic.

EBNA1 gene sequencing.

DNA was prepared from cell pellets by standard methods, and the relevant regions of the EBNA1 gene were amplified by PCR as follows. The N-terminal coding region was first amplified with the 5′ primer 5′-GTCTGCACTCCCTGTATTCA-3′ (B95.8 coordinates 107881 to 107900) and the 3′ primer 5′-CTTTGCAGCCAATGCAA-3′ (B95.8 coordinates 108199 to 108183) under the following PCR conditions (94°C for 30 s, 46°C for 60 s, 72°C for 120 s, 35 cycles). The C-terminal coding region was first amplified with the 5′ primer 5′-GAAAAGAGGCCCAGGAGTCCCAGTAGTCAG-3′ (B95.8 coordinates 109081 to 109110) and the 3′ primer, 5′-AACAGCACGCATGATGTCTACTGGGGATTT-3′ (B95.8 coordinates 109969 to 109940) under the following PCR conditions (94°C for 60 s, 62°C for 90 s, 72°C for 240 s, 35 cycles). The PCR products were then gel purified with a Qiaex agarose gel extraction kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then sequenced by PCR with a Perkin-Elmer Amplicycle kit (Perkin-Elmer/Applied Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom) and either the above primers or, for the C-terminal coding region, the following internal primers: E1 sequence 1 5′-GGTTCCAACCCGAAATTTGA-3′ (B95.8 coordinates 109366 to 109385), E1 sequence 2 5′-AAGGGAGGTCTTACTACCTC-3′ (B95.8 coordinates 109500 to 109481), and E1 sequence 3 5′-AGAAGGCCCAAGCACTGGAC-3′ (B95.8 coordinates 109278 to 109297). All primers were 32P end labeled prior to PCR sequencing under the following conditions (94°C for 30 s, 42°C for 30 s, 70°C for 60 s, 30 cycles).

EBV type and strain analysis.

All BL-associated and normal donor-derived EBV isolates were classified as type 1 or type 2 by using standard PCR assays across type-specific regions of the EBNA2 and EBNA3C genes as described earlier (31). Selected isolates were additionally screened for three polymorphisms of the latent membrane protein (LMP) 1 gene, namely, by the presence or absence of a XhoI restriction site, the presence or absence of the 30-bp deletion, and the number of 33-bp repeats (24); all were assayed by standard PCR methods as described previously (17).

RESULTS

Comparison of BL- and normal B-cell-derived virus strains from endemic BL patients.

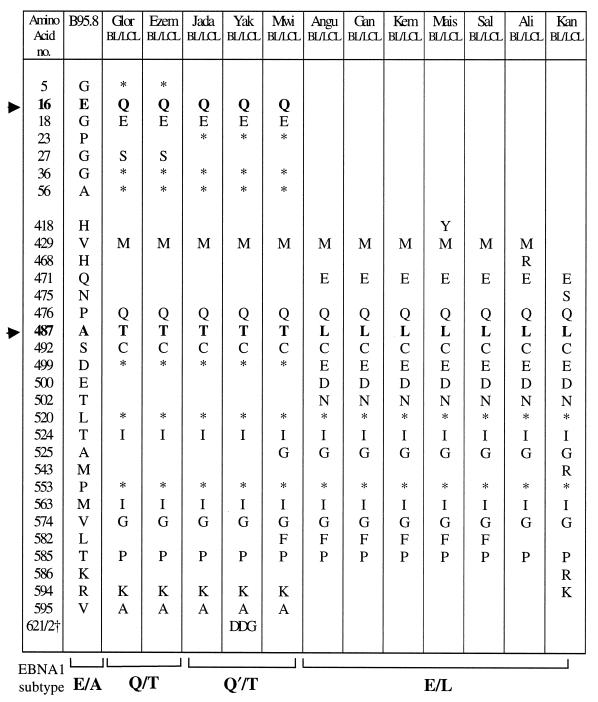

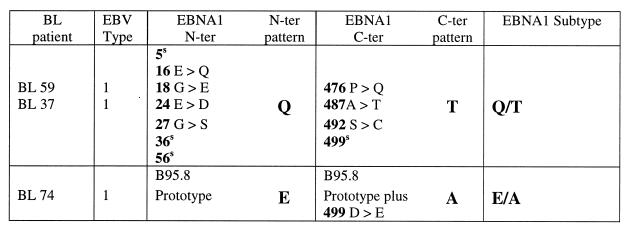

The initial set of experiments focused on 12 East African BL patients (10 Ugandan and 2 Kenyan) from whom a tumor cell line or tumor biopsy cells were available and also on one or more LCLs derived by spontaneous outgrowth from cultures of the patient’s normal peripheral blood B cells. For each of these pairs of isolates, the resident EBNA1 gene was sequenced across codons 1 to 70 and 395 to 641; this covers most of the unique N-terminal and C-terminal regions of the EBNA1 protein, including all positions where amino acid changes have been previously reported (4, 14, 35, 38). The results, summarized in Table 1, show amino acid changes relative to the B95.8 prototype and also show codons with silent nucleotide changes. Most importantly, within each individual pair of BL-derived and normal B-cell-derived virus isolates the EBNA1 nucleotide sequence was identical. However, there were significant differences between pairs, and the individual results are arranged in Table 1 to illustrate the different EBNA1 sequence patterns observed.

TABLE 1.

EBNA1 sequence changes in East African BL/LCL pairs versus the B95.8 prototypea

Symbols: ▸, amino acids 16 and 487, which are the signature residues for the N-terminal and C-terminal sequence patterns determining EBNA1 subtypes; ∗, codons with a silent nucleotide change; †, presence of an additional DDG repeat sequence.

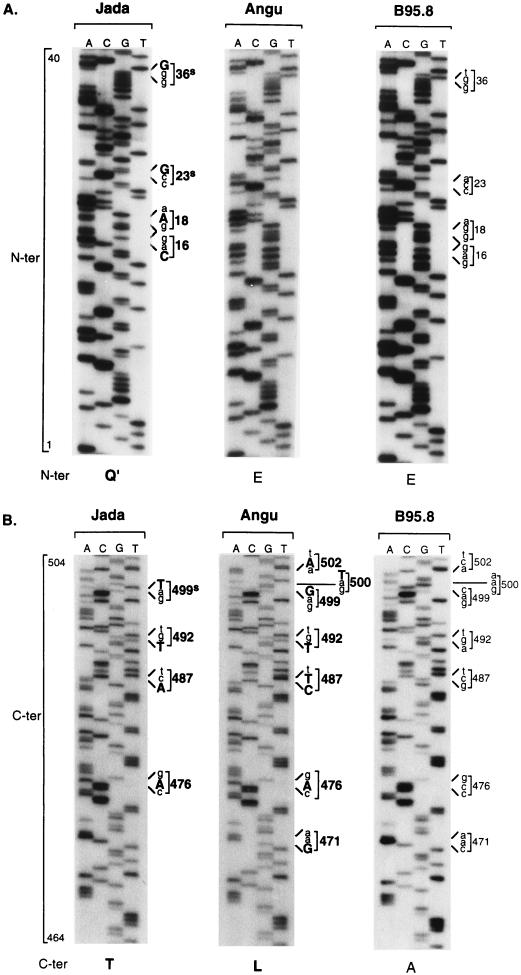

At the N terminus, the sequences were either identical to B95.8 (Angu, Gan, Kem, Mais, Sal, Ali, and Kan) or showed one of two related patterns of polymorphism with coding changes either at residues 16 (E→Q), 18 (G→E), and 27 (G→S), plus silent changes at residues 5, 36, and 56 (Glor and Ezem) or at residues 16 (E→Q) and 18 (G→E), plus silent changes at residues 23, 36, and 56 (Jada, Yak, and Mwi). In the present study, these N-terminal sequence patterns are classified by using amino acid 16 as the signature residue; hence, the B95.8 prototype is classified as E and the above two variant sequences as Q and Q′, respectively. Figure 1A shows representative sequencing gels for codons 1 to 40 of the Jada virus isolate, showing the Q′ pattern of N-terminal sequence changes, and of the Angu virus isolate, which is identical to B95.8. At the C terminus, all 12 pairs of isolates showed sequence changes relative to B95.8 and two broad patterns of variance could be observed. One of these (represented by Glor, Ezem, Jada, Yak, and Mwi) was characterized by coding changes at residues 429, 476, 487, 492, 524, 563, 574, 585, 594, and 595 and silent changes at residues 499, 520, and 553; by using amino acid 487 as the signature residue in accordance with the study by Bhatia et al. (4), this pattern is classified as T. The other C-terminal pattern (represented by Angu, Gan, Kem, Mais, Sal, Ali, and Kan) is characterized by coding changes at residues 429, 471 (in some cases also 475), 476, 487, 492, 499, 500, 502, 524, 525, 563, 574, and 585 and silent changes at residues 520 and 553; from the change at residue 487, this pattern is classified as L. Figure 1B shows sequencing gels covering codons 464 to 504 for the Jada and Angu virus isolates; these illustrate, respectively, the T and L patterns of C-terminal sequence changes vis-à-vis the B95.8 prototype pattern A. Importantly, we noted that virus isolates classified as Q or Q′ at the N terminus all had a T sequence at the C terminus, whereas isolates with the E (B95.8 prototype) sequence at the N terminus all had an L sequence at the C terminus. Hence, the 12 isolates in Table 1 could be arranged into three EBNA1 subtypes with the N-ter/C-ter sequence patterns Q/T, Q′/T, and E/L, all of which were distinct from the B95.8 prototype, E/A.

FIG. 1.

Representative sequencing gels for the Jada-BL, Angu-BL, and B95.8 virus isolates across codons 1 to 40 (N-ter) (A) and codons 464 to 504 (C-ter) (B) of the EBNA1 gene. Nucleotide changes in Jada and Angu relative to the B95.8 prototype are shown in bold capital letters, and codon changes are shown in bold numbers; the corresponding nucleotides and codons in B95.8 are shown in lowercase and lighter print. The N-terminal and C-terminal sequence patterns are identified below the relevant gels by using the signature amino acids at positions 16 and 487, respectively.

Comparison of these BL- and normal B-cell-derived viruses from the same individual was then extended to other known polymorphic loci. These included type-specific polymorphisms in the EBNA2 and EBNA3C genes (31) and three strain-specific polymorphisms in the LMP1 gene (24). The results of this analysis, summarized in Table 2, further indicate that for any one patient the virus present within the tumor is indistinguishable from that present within the normal B-cell pool. In each case the paired isolates were identical at all of the polymorphic loci examined. In several cases multiple independent virus isolates had been rescued from the normal B-cell pool by spontaneous outgrowth, and these were always identical to one another as well as to the matched BL isolate. It is also clear from Table 2 that the patterns of EBNA1 sequence variation identified in the first set of experiments do not correlate with virus type, since most of the viruses were of type 1, including strains classified as Q/T, Q′/T, or E/L at the EBNA1 locus.

TABLE 2.

Screening of East African BL-LCL pairs at various polymorphic loci

| Patient | EBV source | EBNA1 subtype | EBNA2/ 3C type | LMP1 repeats | LMP1 deletion | LMP1 XhoI site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali | BL cell line | E/L | 1 | 6 | Deleted | Present |

| spLCL | E/L | 1 | 6 | Deleted | Present | |

| Angu | BL cell line | E/L | 1 | 4.5 | Deleted | Present |

| spLCL | E/L | 1 | 4.5 | Deleted | Present | |

| Ezem | BL cell line | Q/T | 1 | 4 | Wild type | Present |

| spLCLs 1–10 | Q/T | 1 | 4 | Wild type | Present | |

| Gan | BL cell line | E/L | 1 | 6 | Deleted | Present |

| spLCL | E/L | 1 | 6 | Deleted | Present | |

| Glor | BL cell line | Q/T | 1 | 4 | Wild type | Present |

| spLCLs 1–5 | Q/T | 1 | 4 | Wild type | Present | |

| Jada | BL cell line | Q′/T | 1 | 4.5 | Wild type | Present |

| spLCLs 1–10 | Q′/T | 1 | 4.5 | Wild type | Present | |

| Kan | BL cell line | E/L | 2 | 4.5 | Wild type | Present |

| spLCL | E/L | 2 | 4.5 | Wild type | Present | |

| Kem | BL cell line | E/L | 1 | 4.5 | Deleted | Present |

| spLCLs 1–2 | E/L | 1 | 4.5 | Deleted | Present | |

| Mais | BL cell line | E/L | 1 | 4.5 | Deleted | Present |

| spLCL | E/L | 1 | 4.5 | Deleted | Present | |

| Mwi | BL cell line | Q′/T | 1 | 5 | Wild type | Present |

| spLCL | Q′/T | 1 | 5 | Wild type | Present | |

| Sal | BL cell line | E/L | 1 | 5 | Deleted | Present |

| spLCLs 1–2 | E/L | 1 | 5 | Deleted | Present | |

| Yak | BL cell line | Q′/T | 1 | 2 | Wild type | Lost |

| spLCL | Q′/T | 1 | 2 | Wild type | Lost |

EBNA1 subtype distribution among BL- and control donor-derived viral strains from particular geographic areas.

To allow a more extensive analysis of EBNA1 subtype distribution among virus strains from BL patients and control donors, we elected to sequence all isolates across codons 1 to 60 and 460 to 510 of the EBNA1 gene. As is clear from Table 1, these regions of EBNA1 contain many of the informative N- and C-terminal polymorphisms, including the signature codons 16 and 487, respectively.

(i) East African BL patients and controls.

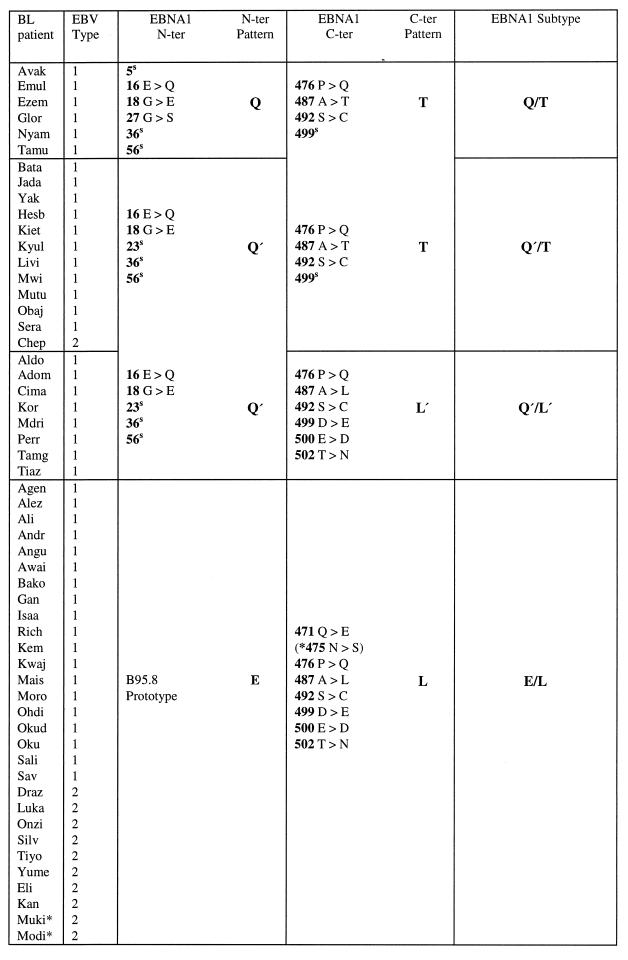

In all, we studied 55 cases of BL, either as recently established cell lines or as fresh tumor cell suspensions, from classical tumor-endemic regions of Uganda and Kenya. The distribution of BL-associated EBNA1 subtypes was very similar in the two countries, and so the data were combined. Table 3 summarizes the changes observed for all 55 BL-derived virus isolates over the designated N- and C-terminal regions vis-à-vis the B95.8 prototype sequence. In all, four distinct EBNA1 subtypes could be identified. Thus, 6 of 55 BL isolates displayed the Q/T pattern, 12 of 55 displayed the Q′/T pattern, and 29 of 55 displayed the E/L pattern; these three subtypes have already been introduced in the sequencing study shown in Table 1. In addition, the remaining 8 of 55 BL isolates showed the Q′ pattern at the N terminus with a C-terminal sequence that was identical to the L sequence except for the absence of a change at codon 471 and the presence of an alternative codon (GAC as opposed to GAT) at residue 500; in view of these differences plus the consistent association of this L-related sequence with Q′ (as opposed to E) at the N terminus, it was classified as L′. We noted that type 1 BL isolates, which constituted 80% of the total, were distributed among all four EBNA1 subtypes; by contrast 10 of 11 type 2 isolates were clustered in the E/L subtype group.

TABLE 3.

EBNA1 subtypes among East African BL isolates: sequence changes versus B95.8 prototypea

A superscript “s” identifies codons with a silent nucleotide change, and an asterisk identifies E/L isolates with an additional change at position 475.

The study then focused on viral strains isolated from 32 control donors from the same BL-endemic areas. Again, it was possible to combine the data from Ugandan and Kenyan donors since there was no significant difference between them in terms of EBNA1 subtype distribution. Table 4 summarizes the data from all 32 control donor isolates, with the information presented in the same format as that used above. Five different EBNA1 subtype patterns were observed, including all four subtypes identified among the BL isolates from East Africa. Thus, 7 of 32 control isolates displayed the Q/T pattern, albeit in three cases with an additional coding change at position 24 in the N-terminal sequence; a further 7 of 32 control isolates displayed the Q′/T pattern, 2 of 32 displayed Q′/L′, and 12 of 32 displayed E/L. The remaining 4 of the 32 isolates carried previously identified N- and C-terminal sequences but in a novel combination, namely, Q/L. As in the series of BL isolates, type 1 viruses were in the majority among the control isolates and were heterogeneous in terms of EBNA1 subtype, being represented within the Q/T, Q′/T, Q′/L′, and E/L subtype groups. Of the type 2 isolates from control donors, some were clustered within the E/L subtype group (like the type 2 BL isolates), while the others formed the newly identified Q/L subtype.

TABLE 4.

EBNA1 subtypes among East African control isolates: sequence changes versus the B95.8 prototypea

A superscript “s” identifies codons with a silent nucleotide change, and an asterisk identifies Q/T or E/L isolates with an additional change at positions 24 and 475, respectively.

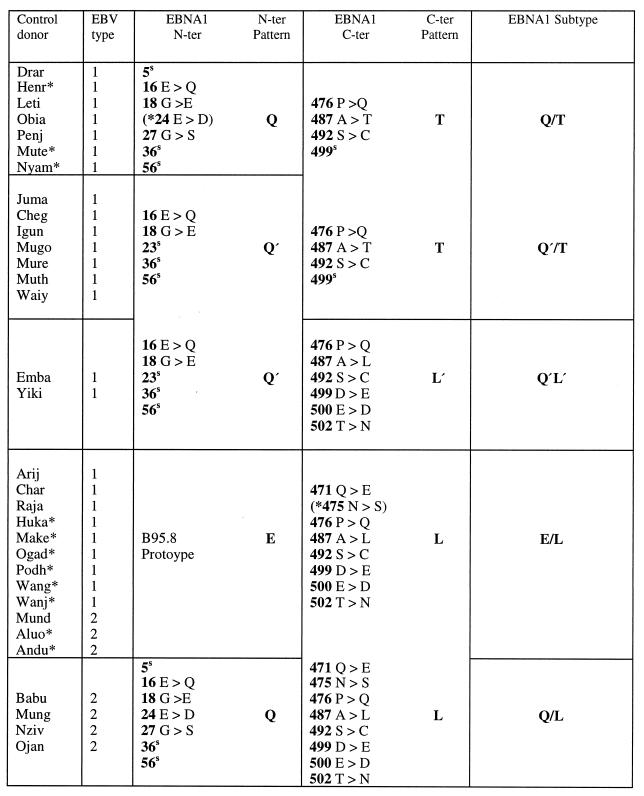

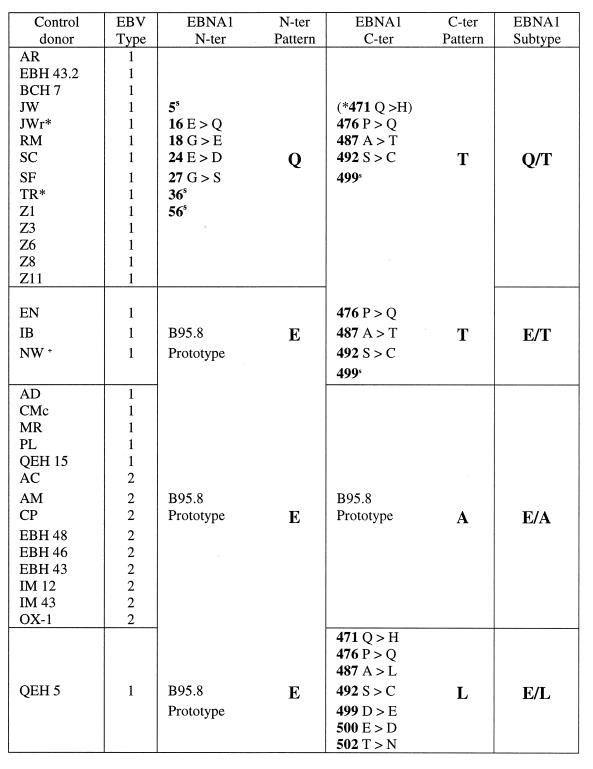

(ii) European BL patients and controls.

EBV genome-positive tumors form a small minority of the sporadic BL cases arising in Europe (23) and only three cases, all carrying a type 1 virus strain, were available for analysis (29). The data from these cases are shown in Table 5. Two tumors showed a typical Q/T EBNA1 subtype pattern with a series of coding and silent changes identical to those seen in Q/T isolates from East Africa. The third tumor followed the B95.8 prototype sequence at both the N and the C termini (except for a single codon change at residue 499) and was therefore classified as EBNA1 subtype E/A.

TABLE 5.

EBNA1 subtypes among European BL isolates: sequence changes versus the B95.8 prototypea

A superscript “s” identifies codons with a silent nucleotide change.

We then screened 32 EBV strains from European control donors, all isolated by spontaneous outgrowth of cultured blood lymphocytes. This panel was composed of 23 type 1 and 9 type 2 virus isolates; note that the proportion of type 2 strains among Caucasian EBV isolates is usually only 5 to 10% (39, 41) but that this was deliberately increased in the present panel to allow an equal number of European and African type 2 viruses to be compared. The data, summarized in Table 6, show that the two most predominant EBNA1 subtypes among the control isolates are the two already seen in the European BLs. Thus, 14 of 32 control isolates were of the Q/T subtype and a further 14 of these were of the B95.8-like subtype. In addition, one control isolate showed the E/L subtype pattern common among East African virus strains, while a further three control isolates displayed a novel combination of a B95.8-like N-terminal sequence and a T pattern at the C terminus; hence, they were classified as E/T. Again, type 1 virus strains were represented in all of the EBNA1 subtype groups, whereas the type 2 viruses were clustered into a single group, in this case the B95.8 EBNA1 subtype, E/A.

TABLE 6.

EBNA1 subtypes among European control isolates: sequence changes versus the B95.8 prototypea

A superscript “s” identifies codons with a silent nucleotide change, and an asterisk identifies Q/T isolates with an additional change at position 471. +, Sequencing of the whole EBNA1 C terminus in isolate NW confirms that it follows the same T pattern as in Table 1.

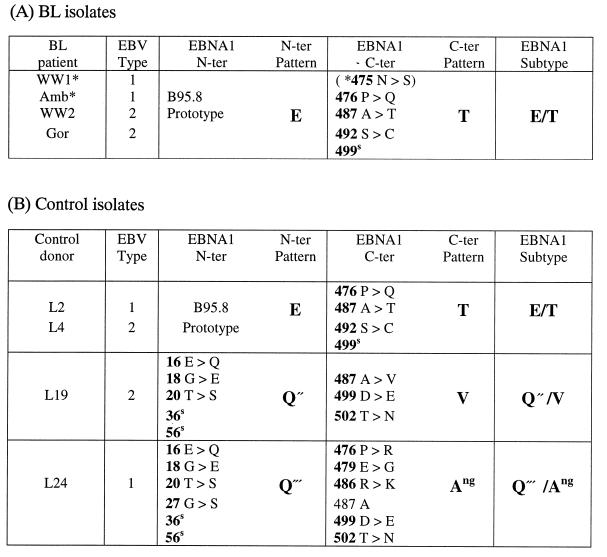

(iii) New Guinea BL patients and controls.

Although there were limited numbers of BL cell lines and normal control isolates available from New Guinea, we felt it important to include these in the analysis since New Guinea is the only region outside equatorial Africa with classical endemic BL (23). The summary data are shown in Table 7. All four BL cases (two type 1 and two type 2) displayed an E/T EBNA1 subtype pattern, hitherto never seen in East Africa and seen only as a rare subtype among the European control donors. Importantly, this same pattern was also shown by two of the four control isolates from New Guinea (one type 1 and one type 2). The other two New Guinea control donors carried quite different EBNA1 sequence combinations. Both were characterized by N termini that were variants of the Q sequence and were, for the present purpose, classified as Q" and Q‴. The Q" sequence was found in association with a C terminus with coding changes at positions 487, 499, and 502 that was designated as V from the signature residue at position 487, hence giving the subtype Q"/V. The other virus had a hitherto unreported C-terminal sequence with multiple changes relative to the B95.8 prototype but retaining the A residue at position 487, giving the subtype Q‴/Ang.

TABLE 7.

EBNA1 subtypes among New Guinea isolates: sequence changes versus B95.8a

A superscript “s” identifies codons with a silent nucleotide change, and an asterisk identifies BL isolates with the E/T EBNA1 subtype that have an additional change at position 475.

The overall data comparing EBNA1 subtype distributions among BL- and control donor-derived viral strains from East Africa, Europe, and New Guinea are summarized in Table 8.

TABLE 8.

Summary of EBNA1 subtype distributions

| EBNA1 subtype | Subtype distributions in:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Africa

|

Europe

|

New Guinea

|

||||

| BL | Controls | BL | Controls | BL | Controls | |

| Q/T | 6 | 7 | 2 | 14 | ||

| Q′/T | 12 | 7 | ||||

| Q′/L′ | 8 | 2 | ||||

| Q/L | 4 | |||||

| E/L | 29 | 12 | 1 | |||

| E/T | 3 | 4 | 2 | |||

| E/A | 1 | 14 | ||||

| Q"/V | 1 | |||||

| Q‴/Ang | 1 | |||||

DISCUSSION

The present study was prompted by reports from Bhatia and colleagues (4, 14) suggesting that EBV strains with particular EBNA1 sequences in the C-terminal 466 to 527 region, especially a sequence designated V-leu, were preferentially associated with both the endemic and nonendemic forms of BL. These authors could not detect the V-leu sequence by direct amplification from the blood and/or throat washings of their control donors, but they did detect up to four other C-terminal sequences in these control samples, often with more than one sequence present in the same individual. The sequences were designated as “prototype” if they were identical or closely related to B95.8 (i.e., P-ala or P-thr, with residue 487 as the signature residue) or “variant” if they were more distant from the B95.8 sequence (i.e., V-pro or V-val). Because these variants were only detected in the presence of a coresident prototype sequence, these authors suggested that the variants were being generated de novo by ongoing mutations in the EBNA1 gene (14); more recent observations of EBNA1 sequences in EBV-positive nasal T-cell lymphomas have been interpreted in a similar way (15). This led to a scenario for BL pathogenesis in which the tumor selectively involves a rare EBNA1 variant that has arisen in the patient against the background of a preexisting infection with a prototype virus. Our immediate objective, therefore, was to look for evidence of such events by comparing the tumor-derived virus strain from that independently isolated from the patient’s normal B-cell pool. In all 12 cases of endemic BL studied, the pairs of isolates had identical EBNA1 sequences (Table 1) and indeed were also concordant at several other polymorphic loci (Table 2). The only way in which such data can be reconciled with the above hypothesis would be if the postulated lymphomagenic variant were to become the dominant virus in the patient’s general B-cell pool or were to be selectively rescued from that pool in vitro. Though such explanations remain formally possible, we consider them to be unlikely in view of the results obtained in the remainder of this study.

Our subsequent objective was to reexamine the question of EBNA1 subtype distribution among BL-derived versus control donor-derived viral isolates but now focusing within more-circumscribed geographic areas than were used in the original reports (4, 14). In this context we would point out that our control virus sequences were all amplified from in vitro isolates rescued by spontaneous LCL outgrowth rather than by being amplified directly from ex vivo lymphocyte preparations. We think that this is unlikely to be a major source of error since, at least for healthy European virus carriers, we find that the EBNA1 subtype of the derived LCL accurately reflects the dominant virus strain detectable in the blood by direct amplification (15a); however, we acknowledge that this might not necessarily be the case for virus carriers in BL-endemic areas. With this caveat, our study went ahead with a unique collection of BL and control donor isolates built up over several years from two geographically adjacent areas of East Africa in which BL occurs in its classical endemic form. The work was then extended to rare cases of EBV-positive sporadic BL occurring in Europe, again compared to a large group of controls, and finally to a limited number of BL and control donor samples from a second quite different BL-endemic area, namely New Guinea. Our results (Tables 3 to 8) lead to the following conclusions.

First, as earlier work has implied (14, 35), it is necessary to identify both N- and C-terminal sequences to gain a true picture of EBNA1 subtype polymorphism. Within any one geographic area, certain N- and C-terminal signature sequences tend to be present in particular combinations; however, one cannot use the sequence at the N terminus as a predictor of the C-terminal sequence pattern (or vice versa) since “recombinant” EBNA1 subtypes also exist. For example, among our European control group the most frequent N-terminal/C-terminal combinations were Q/T and E/A; however, a small number of isolates displayed a different combination, E/T (Table 6). Such a subtype could have been produced by a recombination event within the intervening repeat sequence in the EBNA1 gene. Interestingly, one of the original EBNA1 sequences reported by Wrightham et al. (38), designated AM, likewise appears to be a recombinant, this time within the C-terminal region itself.

Second, different geographic areas have different spectra of EBNA1 subtypes present within their host populations, though these spectra can overlap. Thus, as summarized in Table 8, of the five EBNA1 subtypes found in East African control donors, one of the most common (Q/T) was also prevalent among the European controls. On the other hand, the most common East African subtype (E/L) was found rarely and other subtypes (Q′/T, Q′/L′, and Q/L) were not found at all among the European group. Although only a few isolates were available from New Guinea, of the three EBNA1 subtypes observed, two (Q"/V and Q‴/Ang) were unique to this area, while a third (E/T) was identical to that found in a minority of Europeans. Interestingly, the B95.8 prototype sequence (E/A) was common in Europe but was not seen in either of the other two areas. EBNA1 sequence polymorphisms therefore reinforce the picture of geographic differences between EBV strains that has been built up from earlier studies of other polymorphic loci (1, 2, 10, 17, 18, 21, 24).

Third, the East African and European control groups contained sufficient numbers of type 1 and type 2 isolates to allow tentative conclusions to be drawn regarding EBNA1 subtype polymorphism in relation to EBNA2/EBNA3C virus type. In both geographic areas, type 1 viruses were heterogeneous in terms of EBNA1 subtype, whereas type 2 viruses tended to be more uniform. Thus, East African type 2 isolates either fell into the E/L subtype group or carried a unique subtype Q/L (Table 4), whereas all European type 2 isolates followed the B95.8 EBNA1 prototype E/A (Table 6). These observations agree with earlier results from immunoblotting experiments which suggested that the EBNA1 proteins encoded by type 2 viruses show significantly less size variation than do their type 1 counterparts (43); it may be that within any one host population, type 2 viruses show relatively limited heterogeneity. However, it is important to note that the type 2 isolates from East Africa and those from Europe are quite distinct from one another at the EBNA1 locus. These findings are consistent with the view that both type 1 and type 2 viruses were carried out of Africa in the early days of human migration into Europe and that both have coevolved with their host population since that time. Thus, type 2 virus strains that are found occasionally in the general European population (12, 41) and at increased incidence among HIV-positive homosexuals in that same population (42) (see EBH 43, 46, and 48 [Table 6]) carry a characteristically European EBNA1 sequence and therefore do not represent recent imports from Africa.

Finally, and most importantly, the EBNA1 subtypes associated with BL in any one geographic area are also prevalent among viral strains within the general host population in that same area. The strongest evidence in this context comes from the 55 cases of endemic BL seen in East Africa. Here, the most common BL-associated EBNA1 subtype, E/L, was also the most common subtype seen among the geographically matched control group (Table 8). This makes it clear that virus isolates with a Leu residue at EBNA1 position 487 (V-leu in the terminology of Bhatia and colleagues) are not preferentially associated with the Burkitt tumor but are widespread in the East African population in which the tumor arises. Of course, it might be argued that the high prevalence of such an EBNA1 subtype in the general population could explain why BL occurs with such high frequency in East Africa. However, the EBNA1 subtypes associated with BL in East Africa were not found in tumors in another area of classical BL endemicity, New Guinea; all four New Guinea BLs studied carried a different subtype, E/T, which was also found in two of the four normal donor isolates studied from this region. Likewise, the EBNA1 subtypes seen in the three cases of sporadic BL from Europe fell within the major EBNA1 subtype groups, Q/T and E/A, found in the normal European population. We therefore conclude that there is no obvious relationship, of the kind proposed by Bhatia and colleagues (4, 14) between particular EBNA1 subtypes and the Burkitt tumor; our study is far too small, however, to eliminate the more subtle possibility that certain EBNA1 mutations confer a marginally higher lymphomagenic risk. Whether there is any relationship between particular EBNA1 subtypes and other EBV-positive tumors remains to be seen. On the one hand, the evidence from EBV-positive nasal T-cell lymphomas might suggest this (15). On the other hand, we noted that the particular EBNA1 sequence variant (with a Val residue at position 487) reportedly frequent in Chinese NPC (14, 35) was actually very similar to that present in one of our New Guinea control isolates (L19; Table 7B). Reasoning that this may represent another example of a polymorphism common among Southeast Asian virus strains (10, 18), we recently analyzed several peripheral blood-derived isolates from Chinese control donors and found this EBNA1 variant present in every case (23a). Caution must be exercised, therefore, when data are available from tumor-derived virus strains in the absence of geographically matched control isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the United Kingdom’s Cancer Research Campaign. G.H. is funded by a University of Birmingham Ph.D. scholarship.

We are grateful to G. Lenoir (IARC, Lyon, France) and D. Moss (QIMR, Brisbane, Australia) for access to cell lines, to H. Rupani (Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya) for the earlier supply of Kenyan BL and control blood samples, and to Deborah Williams for excellent secretarial help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdel-Hamid M, Chen J J, Constantine N, Massoud M, Raab-Traub N. EBV strain variation: geographical distribution and relation to disease state. Virology. 1992;190:168–175. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)91202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aitken C, Sengupta S K, Aedes C, Moss D J, Sculley T B. Heterogeneity within the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 gene in different strains of Epstein-Barr virus. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:95–100. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-1-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambinder R F, Mullen M A, Chang Y-N, Hayward G S, Hayward S D. Functional domains of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA1. J Virol. 1991;65:1466–1478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.3.1466-1478.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatia K, Raj A, Gutierrez M I, Judde J-G, Spangler G, Venkatesh H, Magrath I T. Variation in the sequence of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 in normal peripheral blood lymphocytes and in Burkitt’s lymphomas. Oncogene. 1996;13:177–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bochkarev A, Barwell J A, Pfuetzner R A, Bochkareva E, Frappier L, Edwards A M. Crystal structure of the DNA binding domain of the Epstein-Barr virus origin binding protein, EBNA1, bound to DNA. Cell. 1996;84:791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bochkarev A, Barwell J A, Pfuetzner R A, Furey W J, Edwards A M, Frappier L. Crystal structure of the DNA binding domain of the Epstein-Barr virus origin binding protein EBNA1. Cell. 1995;83:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouzid M, Buisson M, Morand P, Perron H, Seigneurin J-M. Different distribution of H1-H2 Epstein-Barr virus variant in oropharyngeal virus and in biopsies of Hodgkin’s disease and in nasopharyngeal carcinoma from Algeria. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:205–210. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980717)77:2<205::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busson P, Edwards R H, Tursz T, Raab-Traub N. Sequence polymorphism in the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP)-2 gene. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:139–145. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-1-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dambaugh T, Hennessy K, Chamnankit L, Kieff E. U2 region of Epstein-Barr virus DNA may encode Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7632–7636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Campos-Lima P-O, Levitsky V, Brooks J, Lee S P, Hu L F, Rickinson A B, Masucci M G. T cell responses and virus evolution: loss of HLA A11-restricted CTL epitopes in Epstein-Barr virus isolates from high A11-positive populations by selective mutation of anchor residues. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1297–1305. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Falk K, Gratama J W, Rowe M, Zou J Z, Khanim F, Young L S, Oosterveer M A P, Ernberg I. The role of repetitive DNA sequences in the size variation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigens, and the identification of different EBV isolates using RFLP and PCR analysis. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:779–790. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-4-779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gratama J W, Oosterveer M A P, Weimar W, Sintnicolaas K, Sizoo W, Bolhuis R L H, Ernberg I. Detection of multiple ’Ebnotypes’ in individual Epstein-Barr virus carriers following lymphocyte transformation by virus derived from peripheral blood and oropharynx. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:85–94. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-1-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory C D, Rowe M, Rickinson A B. Different Epstein-Barr-virus (EBV) B cell interactions in phenotypically distinct clones of a Burkitt lymphoma cell line. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:1481–1495. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-7-1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Griffiths, M., and A. B. Rickinson. Unpublished data.

- 14.Gutierrez M I, Raj A, Spangler G, Sharma A, Hussain A, Judde J-G, Tsao S W, Yuen P W, Joab I, Magrath I T, Bhatia K. Sequence variations in EBNA1 may dictate restriction of tissue distribution of Epstein-Barr virus in normal and tumour cells. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1663–1670. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-7-1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutierrez M I, Spangler G, Kingma D, Raffeld M, Guerrero I, Misad O, Jaffe E S, Magrath I T, Bhatia K. Epstein-Barr virus in nasal lymphomas contains multiple on-going mutations in the EBNA1 gene. Blood. 1998;92:600–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Habeshaw, G., and A. B. Rickinson. Unpublished observations.

- 16.Hu L F, Chen F, Zheng X, Ernberg I, Cao S-L, Christensson B, Klein G, Winberg G. Clonability and tumorigenicity of human epithelial cells expressing the EBV encoded membrane protein LMP1. Oncogene. 1993;8:1575–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khanim F, Yao Q Y, Niedobitek G, Sihota S, Rickinson A B, Young L S. Analysis of Epstein-Barr virus gene polymorphisms in geographically distinct virus isolates of normal donor and tumour origin. Blood. 1996;88:3562–3568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanna R, Slade R W, Poulsen L M, Moss D J, Burrows S R, Nicholls J, Burrows J M. Evolutionary dynamics of genetic variation in Epstein-Barr virus isolates of diverse geographical origins: evidence for immune pressure-independent genetic drift. J Virol. 1997;71:8340–8346. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8340-8346.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knecht H, Bachmann E, Brousset P, Sandvej K, Nadal D, Bachmann F, Odermatt B F, Delsol G, Pallesen G. Deletions within the LMP1 oncogene of Epstein-Barr virus are clustered in Hodgkin’s disease and identical to those observed in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Blood. 1993;82:2937–2942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S-M, Chang Y-S, Liu S-T. Effect of a 10 amino acid deletion on the oncogenic activity of latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus. Oncogene. 1996;12:2129–2135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lung M L, Lam W P, Chan K H, Li S, Sham J, Choy D. Direct detection of Epstein-Barr virus in peripheral blood and comparison of Epstein-Barr virus genotypes present in direct specimens and lymphoblastoid cell lines established from nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients and healthy carriers in Hong Kong. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:174–177. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lung M L, Lam W P, Sham J, Chong D, Zong Y S, Guo H Y, Ng M H. Detection and prevalence of the “f” variant of Epstein-Barr virus in Southern China. Virology. 1991;185:67–71. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90754-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magrath I. The pathogenesis of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Adv Cancer Res. 1990;55:133–269. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Midgley, R., and A. B. Rickinson. Unpublished observations.

- 24.Miller W E, Edwards R H, Walling D M, Raab-Traub N. Sequence variation in the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2729–2740. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-10-2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pope J H, Achong B G, Epstein M A. Burkitt lymphoma in New Guinea: establishment of a line of lymphoblasts in vitro and description of their fine structure. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1967;39:933–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rickinson A B, Young L S, Rowe M. Influence of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA2 on the growth phenotype of virus-transformed B cells. J Virol. 1987;61:1310–1317. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1310-1317.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rooney C M, Gregory C D, Rowe M, Finerty S, Edwards C F, Rupani H, Rickinson A B. Endemic Burkitt’s lymphoma: phenotypic analysis of Burkitt’s lymphoma biopsy cells and of the derived tumor cell lines. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1986;77:681–687. doi: 10.1093/jnci/77.3.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rowe M, Rooney C M, Rickinson A B, Lenoir G M, Rupani H, Moss D J, Stein H, Epstein M A. Distinctions between endemic and sporadic forms of Epstein-Barr virus-positive Burkitt’s lymphoma. Int J Cancer. 1985;35:435–442. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910350404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rowe M, Rowe D T, Gregory C D, Young L S, Farrell P J, Rupani H, Rickinson A B. Differences in B cell growth phenotype reflect novel patterns of Epstein-Barr virus latent gene expression in Burkitt’s lymphoma cells. EMBO J. 1987;6:2743–2751. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02568.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sample J, Young L, Martin B, Chatman T, Kieff E, Rickinson A. Epstein-Barr virus type 1 (EBV-1) and 2 (EBV-2) differ in their EBNA-3A, EBNA-3B, and EBNA-3C genes. J Virol. 1990;64:4084–4092. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.9.4084-4092.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sandvej K, Gratama J W, Munch M, Zhou X-G, Bolhuis R L H, Andresen B S, Gregersen N, Hamilton-Dutoit S. Sequence analysis of the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 gene and promoter region: identification of four variants among wild-type EBV isolates. Blood. 1997;90:323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schuster V, Ott G, Seidenspinner S, Kreth H W. Common Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) type 1 variant strains in both malignant and benign EBV-associated disorders. Blood. 1996;87:1579–1585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu N, Tanabe-Tochikuru A, Kuroiwa Y, Takada K. Isolation of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-negative cell clones from the EBV-positive Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL) line Akata: malignant phenotypes of BL cells are dependent on EBV. J Virol. 1994;68:6069–6073. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6069-6073.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snudden D K, Smith P R, Lai D, Ng M H, Griffin B. Alterations in the structure of the EBV nuclear antigen, EBNA1, in epithelial cell tumors. Oncogene. 1995;10:1545–1552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sugden B, Warren N. A promoter of Epstein-Barr virus that can function during latent infection can be transactivated by EBNA1, a viral protein required for viral DNA replication during latent infection. J Virol. 1989;63:2644–2649. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.6.2644-2649.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilson J B, Bell J L, Levine A J. Expression of Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1 induces B cell neoplasia in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 1996;15:3117–3126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wrightham M N, Stewart J P, Janjua N J, Pepper S D V, Sample C, Rooney C M, Arrand J R. Antigenic and sequence variation in the C-terminal unique domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen EBNA-1. Virology. 1995;208:521–530. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yao Q-Y, Croom-Carter D S G, Tierney R J, Habeshaw G, Wilde J T, Hill F G H, Conlon C, Rickinson A B. Epidemiology of infection with Epstein-Barr virus types 1 and 2: lessons from the study of a T-cell immunocompromised hemophilic cohort. J Virol. 1998;72:4352–4363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4352-4363.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao Q Y, Ogan P, Rowe M, Wood M, Rickinson A B. Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells persist in the circulation of acyclovir-treated virus carriers. Int J Cancer. 1989;43:67–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910430115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao Q Y, Rowe M, Martin B, Young L S, Rickinson A B. The Epstein-Barr virus carrier state: dominance of a single growth-transforming isolate in the blood and in the oropharynx of healthy virus carriers. J Gen Virol. 1991;72:1579–1590. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-72-7-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao Q Y, Tierney R J, Croom-Carter D, Dukers D, Cooper G M, Ellis C J, Rowe M, Rickinson A B. Frequency of multiple Epstein-Barr virus infections in T-cell-immunocompromised individuals. J Virol. 1996;70:4884–4894. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.4884-4894.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young L S, Yao Q Y, Rooney C M, Sculley T B, Moss D J, Rupani H, Laux G, Bornkamm G W, Rickinson A B. New type B isolates of Epstein-Barr virus from Burkitt’s lymphoma and from normal individuals in endemic areas. J Gen Virol. 1987;68:2853–2862. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-68-11-2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]