Abstract

In the context of research on children's life satisfaction, considering children as active participants are very scarce, the main purpose of the present study was to examine children's perspectives on their life satisfaction. The study used a convenient sample of 228 students from primary and secondary schools, living in urban and suburban areas in Vietnam. The subjects’ average age is 9.51 (SD = 1.56). Data were collected using a single open-ended question. The data analysis was performed by thematic analysis then processed with SPSS 22.0 for quantitative assessment. The results of data analysis indicate the following criteria to consider a child as being satisfied with life: (1) Quality of social relationship; (2) Quality of family relationship; (3) Being engaged in interesting and fun leisure and activities; (4) Achieving desired goals; (5) Living environment; and (6) Some other external factors. Among these qualities, the most important relationships in their lives (including social and family relations) were chosen with the highest frequency, followed by their engagement in meaningful and fun activities, and pursuit of their desired goals. This study provided a better insight into understanding how children perceive life satisfaction and what meanings they attach to it. The research results might be explained from a socio-cultural perspective and provide a scientific basis for large-scale studies on this topic in Vietnam.

Keywords: Children's life satisfaction, categories of life satisfaction, qualitative study, Asian culture, Vietnam

Introduction

From the time of Aristotle, the pursuit of happiness and the achievement of the “good life” has been a major concern among philosophers and theologians. 1 In psychology, it was included as one of three crucial missions of the discipline.2,3 However, for a long time, this mission has seemingly been neglected and has not received the appropriate attention from psychologists. Thus, in forming a complete understanding of psychological phenomena, researchers must investigate factors that contribute to psychological well-being, in addition to those related to mental disorders. In recent decades, only with the birth of positive psychology did researches on happiness or subjective well-being (SWB) truly take off. Despite the many different conceptualizations of SWB, the most commonly accepted model of SWB by Diener and colleagues 4 states that it comprises an emotional component (long-term frequency of positive and negative affect) and a cognitive component (life satisfaction [LS]). However, most existing studies on SWB have focused on adults or relied on adults’ points of view to establish the categories and measurements for those of children. The literature review showed only a few studies that looked into how children define well-being (e.g.5–7) In other words, research on children's SWB has lagged behind. 8 A clear limitation in current literature is that children's opinions were rarely mentioned.5,9 This is considered problematic because adults’ perspectives on the same experience could be different from those of children. As stated by Casas 10 and many other authors,11–13 information on children's lives is most valid when they come from the experts of their lives: children themselves.

Research has indicated that LS has a positive impact on the psychological development of children and adolescents. 14 More specifically, high levels of LS could encourage children and adolescents to explore the world, thus serving as a positive contributor to their growth.15,16 It can be seen that much research that focused on understanding children and adolescents’ LS has led to the construction of numerous global and multidimensional LS measures. 15 However, when reviewing 141 empirical studies, Protor, Linley, and Maltby 17 have suggested that the majority of past research on the topic has occurred within America, with most assessment measures being created and validated among American samples, so “far less information is available elsewhere"(p.1). 18 The literature review allowed us to access a few studies on LS of Asian children such as Korean and China children, etc., but like most studies in the world, these studies also did not approach from the child's perspective on this subject.19–22 This has led to cultural differences/gaps in understanding certain concepts and establishing global metrics. For example, in Western culture, people are encouraged to seek and affirm their personal qualities. Social relationships are also important, but they are built on the basic assumption of individual independence, motivated by individual strives. Meanwhile, contrary to the Western perspective, the Asian culture views the self as a connection, flexibility, and commitment in relationships with others.23,24 Thus, in Eastern culture, the boundary between individuals and others is unclear and often compromised through social interactions. This created the necessity of conducting research on LS of children and adolescents across different cultures, specifically Asian countries such as Vietnam.

Furthermore, the review of extant findings in the youth LS literature indicates that the majority of research on the topic has adopted quantitative methodology. Particularly, when reviewing the studies on children and adolescents' LS, Gilman and Huebner 15 pointed out that the most common technique for measuring student LS is the self-report scale. However, this method is inherently associated with certain potential limitations (e.g. social desirability). Meanwhile, qualitative studies sought to understand children's perspectives on the matter as active participants are very scarce (e.g.25–27) Therefore, further research whose methodology allows insight into children's subjective perspective on the subject is necessary to develop a more comprehensive LS. Due to the lack of such an approach in this area, we considered the qualitative methodology as the core approach in gathering and analyzing data for the present study.

Thus, the present study aims to investigate how children perceive or understand the concept of LS using qualitative data in a Vietnamese sample. We speculate that the findings in our study would help enlighten our understanding of the conceptualization of LS in different cultural. The research hypotheses were as follows: (1) Children perceived LS as a complex and multi-dimensional concept, and (2) Children were most satisfied when having a good relationship with others, including relationships with family members, friends, teachers and others.

Choice of methodology

While the most common technique for measuring LS is using self-report scales, the use of qualitative assessment methods, such as open-ended questions, allows the collection of information on participants' perceptions, views, and beliefs in their own terms, in contrast to the external definitions and categories preestablished by researchers, which is typical of quantitative inquiries. 28 As mentioned by Patton, 29 the truly open-ended question “allows the person being interviewed to select from among that person's full repertoire of possible responses….” (p. 296). This methodology allows free expression of individual comments and opinions from the interviewees and can be used for a wide range of applications. Particularly, it is useful for exploring new topics or understanding complex issues. 30 In addition, Patton 29 also confirmed that qualitative methods have an important unique advantage which is that qualitative data can be transferred into quantitative data for research purposes. On such a basis, collected information can be deployed on a large number of subjects.

In this paper, through qualitative analyzes of data collected from an open-ended question, we investigated how children define LS in their own terms. From these qualitative findings, we expected to get new insights into the Vietnamese children's definition of LS, thus, laying the foundation for constructing a reliable and valid psychometric scale for measuring the level of Vietnamese children's LS in the future.

Participants and procedure

Purposive sampling

In line with the research's aim, we chose to collect data from schools because as part of the compulsory school system, primary and secondary schools allow access to the full spectrum of social demographic profiles of a child. Thus, the most common sampling procedure for qualitative research: purposeful sampling was used.31,32

Respondents comprised of students from two areas (the urban and suburban) of X city in Vietnam. A sample of 228 students from primary and secondary schools participated in the study. The sample consisted of 55.30% males with an average age of 9.51 years (SD = 1.56). In line with Patton, 33 students from 8 to 12 years old were chosen as respondents because of the advantage of homogeneity in terms of psychological development. Table 1 presents the detailed socio-demographic information on children in our study:

Table 1.

Participant's demographic characteristics.

| Demographic | Characteristics | Number of participants | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 126 | 55.3 |

| Female | 102 | 44.7 | |

| Age | 8 years old | 68 | 29.8 |

| 10 years old | 81 | 35.5 | |

| 12 years old | 79 | 34.7 | |

| Living area | Suburban | 138 | 60.5 |

| Urban | 90 | 39.5 |

Measurement

A questionnaire, including two closed-ended demographic questions and one open-ended question on LS, was delivered to all participants. Participants were invited to define LS in their own words through a single open-ended question: “When do you feel most satisfied with your life?”. Two close-ended questions helped us collect some information about the socio-demographics of the population, namely, age and gender, that will be used for further analysis in another quantitative phase.

Procedure

Within the scope of this research, in order to collect the students' answers to occur auspiciously and legally, we utilized the gatekeeper as part of the data collecting method. While in research that occurs in public space, such as streets, parks, public markets, and so on, researchers are usually exempted from getting the gatekeepers' permissions, researches that take place within school campus needs permissions from both participants and school officials. The reason is, legally, all institutions have an autonomous right to permit or deny access to their information, space, and personnel. Thus, for the study, during the surveying process, we had to mobilize the principals and the teachers to receive permission prior to collecting responses from students.

With the permission of these gatekeepers, we carried out the data collection from the students. All the participants and their parents were informed about the specific objective of the study before proceeding to fill out the questionnaire. According to the most recent periodic examination records provided by the school administrators, all participants had normal health conditions, had above-average academic grades, had no records of repeat class or school violence, and had no mental abnormalities based on homeroom teacher perception. Participants were able to complete the survey only once and could terminate the survey at any time they desired. Anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were ensured.

Coding process

Coding was completed by the three authors of this article. The process involved three stages, namely, planning, checking, and finalizing. In the planning stage, we carefully read and re-read each answer given by each participant and familiarized ourselves with the opinions expressed by children included in our study. During this phase, every member of the research team sorted out quotes and noted any questions, ideas, or explanations that emerged. After the discussion, two researchers began coding the answers obtained. A preliminary coding plan was constructed, and all potentially relevant features were included.

The checking stage involves comparing the two coding versions. One by the aforementioned researchers and the other, conducted independently by the remaining author. Based on the preliminary coding results, a revised coding plan was brought about with an adjusted number of the coding features. Specifically, the number of codes was reduced from 24 to 15 codes for the 942 responses collected from participants.

In the finalizing stage, all the answers were coded carefully again by all three authors and put into five categories based on the revised coding plan. Throughout this procedure, the codes were further refined, and the results are illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

The final analytical framework with constituent codes, categories, and description.

| Theme/Category | Codes | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of family relationship | Warm, happy family with siblings who get along, everyone is healthy. | Members of the family get along, are happy, and play together; everyone is healthy. |

| Being cared for, loved, taken care of and supported by parents, grandparents. | The idea of receiving compliments, love, encouragement and care from members of the family. | |

| Can support parents, grandparents, relatives in the family. | The idea of being able to help grandparents, parents in doing house-works. | |

| Quality of social relationship | Have good friend, likable friend, friends who get along and help one another. | Relate to the desire of having many good friends, getting along with friends, closely-knitted friends who support one another in study and in life. |

| Be able to go to school, play, and participate in activities with friends. | The way that children perceive their friendship quality in the school context. | |

| Be respected, loved, supported, complimented and supported by everyone. | Relate to the desire to have positive relationships with everyone around (neighbors, relatives, and even strangers). | |

| Be respected by teachers and able to please teachers. | The need to be respected by teachers, to please the teachers. | |

| Be able to help others. | Children's perception on bringing joy to others, helping those who are struggling. | |

| Engagement in interesting and fun leisure and activities | Take a break from school, go out, participate in outdoors, leisure activities after school hours. | Perception of children related to activities in leisure time. |

| Eat favorite food. | The idea of being able to eat favorite food, good food. | |

| Have books, objects, toys bought for, have gifts given to. | The idea of being bought, gifted things that children life every day and on special occasions like new year, birthday, Christmas. | |

| Achieving desired goals | Good achievements from school activities, school results, learning at a good school. | Expectations on achievements in learning. |

| Achieve dreams, execute personal roles, do what they want. | The desire to do what they wish for, what they want. | |

| Possess good health and physical beauty. | Perception on physical appearances, health of the children themselves. | |

| Living environment | Friendly environment, no more poverty or diseases. | The idea of a peaceful, prosperous society with no poverty, diseases, natural disaster. |

Besides, we noticed some expressions on LS, which were irrelevant to the aspects of life as well as the psychological features mentioned in the coding process. These are temporarily recorded as “other external factors” (e.g. Have nice clothes; Younger brother stop going through backpack; Young sister talks less; To be born).

Results

Categories of LS

During the process of data coding, it was found that all participants were able to form their own opinions about when they were most satisfied with their lives. In other words, no participants considered LS as a vague and indescribable concept. The results of the thematic analysis showed that LS was defined in the following aspects by children:

It is a noticeable feature from our collected data that most children, when asked, define LS as positive and joyful expressions and experiences in their lives. For instance:

“I am most satisfied when helping others. Others help me when I am in need”(Male, 9 years old);

“I am most satisfied when I am complimented by teachers, loved by parents, liked by friends”(Male, 7 years old);

“When I get along with everyone and can expand my exploration everywhere is when I am most satisfied”(Female, 11 years old);

“I am most satisfied with life when my family are always healthy, closed and loving, protect one another”(Female, 7 years old);

“When I get high scores on subjects at school is when I am most satisfied with life”(Female, 10 years old).

As these quotes and the answers shown in Table 3, the children tend to see the times when they feel most satisfied with life in terms of what leads to LS rather than defining what LS is. In other words, the children state that they are content when having a good quality of relationship with family and society, engaging in fun, interesting activities outside of class; pursuing and achieving personal goals; living in a developed, safe and friendly environment. Especially, when discussing the relationship aspects, including family and social relationships, the results revealed that children are likely to be more satisfied when they’re being loved, being cared for, or participating in activities with others. In particular, in family relationships, the answers related to the code “Being cared for, loved, taken care of and supported by parents, grandparents” were mentioned 123 times, taking up nearly 50% (49.9%) of the total of answers found in this category.

Table 3.

Categories of life satisfaction of children.

| Theme/category | Code | Answers obtained | Times mentioned |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of family relationship | Warm, happy family with siblings who get along, everyone is healthy | To have a loving family; Family gathers together; To be with family; Full and gathered family every day; To be with parents; To be with parents during Tet holiday; To be with relatives; To be with parents all week; Dad's recovery from illness; Be with family during birthday; To have both dad and mom; Family goes out together; Hang out with dad and younger sister; Family exercise together; Talk happily with family; Watch a movie with family; Parents' getting along, not fighting; Parents never separate; Siblings compromise with one another; Be able to play with younger siblings. | 88 |

| Being cared for, loved, taken care of and supported by parents, grandparents | When mom cares and spoils; When encouraged, comforted by parents; Being cared for by dad; Being comforted by parents when getting bad grades; Born and grown up in the arms of parents; Being the children of their parents; Getting compliments from parents; Better understood by parents; Getting visited and encouraged by grandparents; Being cared for and loved by grandparents; Having parents organizing a birthday party for; Having their thoughts respected; Having parents coming home early, having dinner with, studying with and hugging during sleep; Pleasing relatives; Not having parents yelled or scolded at, hit. | 123 | |

| Can support parents, grandparents, relatives in the family | Giving back message for grandparents; Helping parents with house works: sweeping the floor, making dinner,… | 38 | |

| Quality of social relationship | Have good friend, likable friend, friends who get along and help one another | Getting along with friends; Friends who get along, close-knitted; Having many good friends; To share with friends; To be supported by friends; Helping friends understand coursework; Helping friends cleaning the classroom; Having friends lending stationary to; Being liked by friends; Not being hated by peers; Being supported by friends; Pleasing friends; Peers in the class like each other. | 77 |

| Be able to go to school, play, and participate in activities with friends | Going to class with friends; Participating in activities outside of class with friends; Play with friends during and after class; Passing on to the next grade; Field trip with the class; Learning the subjects they like; Learning from nice, kind and gentle teacher. | 92 | |

| Be respected, loved, supported, complimented and supported by everyone | Not being ostracized by others; Receiving gratitude from others; Being supported by neighbors; Being complimented by others; Getting compliments from adults; Getting thanks from others; Being loved by others. | 51 | |

| Be respected by teachers and able to please teachers | Being respected, loved and complimented by teachers | 72 | |

| Be able to help others | Bringing joy and laughter to others; Helping those are struggling in life; Doing good deeds; Helping the beggar; Having found 500.000 VND and returned to the owner; Helping the poor; Helping a first grader who fell over; Helping teachers clean the class; Pleasing the teachers. | 50 | |

| Engagement/Being engaged in interesting and fun leisure and activities | Take a break from school, go out, participate in outdoors, leisure activities after school hours | Going to the circus; Watching television; Playing football; Reading stories; Reading books; Parents' allowing me to play games; Getting asked to hangout by friends; Going out during Moon Festival; Going swimming; Winning a game; Staying at home; Exercising every morning; Going to the park; Going out on the weekend; Going to the supermarket; Going on field trips; Going to the museum; Visiting grandparents in the countryside; Going on trips by plane; Visiting countries around the world; Staying in a mansion, five-star hotels; Exploring new places; Sleeping in late. | 122 |

| Eat favorite food | Getting bought good food from parents; Eating good food; Eating ice cream; Eating good candies; Having parents taking out for food; Eating a nice meal made by mom; Eating fried chickens. | 24 | |

| Have books, objects, toys bought for, have gifts given to | Getting given birthday gifts; Being brought comic books for; Being brought nice clothes for; Being brought Lego, toy train, Pokémon storybooks for; Being brought nice dresses; teddy bears, pens for; Having mom brought Christmas gifts for. | 29 | |

| Achieving desired goals | Good achievements from school activities, school results, learning at a good school | Studying well; Getting grade 10; Getting good grades; Getting Good student title; Achieving awards; Getting a certificate of merit; Studying well in all subjects; Studying at a good school; Studying at a fancy school; Being class representatives. | 95 |

| Achieve dreams, execute personal roles, do what they want | Doing something difficult that no one did before; Exploring world's mysteries; Going to space; Traveling around the world; Making a lot of money; Achieving dreams in the future; Fulfilling a duty of son/daughter; Being a good son/daughter; Being proud of oneself; Having mansions, tennis court, hot-air balloons and a good future; Having found my own happiness; Living a happy life; Doing everything I want. | 40 | |

| Possess good health and physical beauty | Tall, pretty, healthy body; Possessing good health. | 5 | |

| Living environment | Friendly environment, no more poverty or diseases | No more thievery, bad guys; Everyone's having enough food, clothes, jobs; No more poverty, natural disaster, kidnap or killing; No more bad guys; Everyone's living in happiness, harmony and joy; The disabled can live happily; The country grows economically; No more COVID; No one's throw trash out, taking care of trees; no more deforestation in order to protect the environment. | 20 |

| Others | Others external factors | Being fed well and dressed well; Having nice clothes; Being free, Getting quiet time; Being a boy (currently a girl), Young brother stops going through backpack; Young sister talks less; Being born. | 16 |

Similarly, in the social relationship aspect, 92 out of 342 answers (taking up 26.90%) stated that satisfaction is when they are “able to go to school, play, and participate in activities with friends.”

Major domains of life that contribute to LS

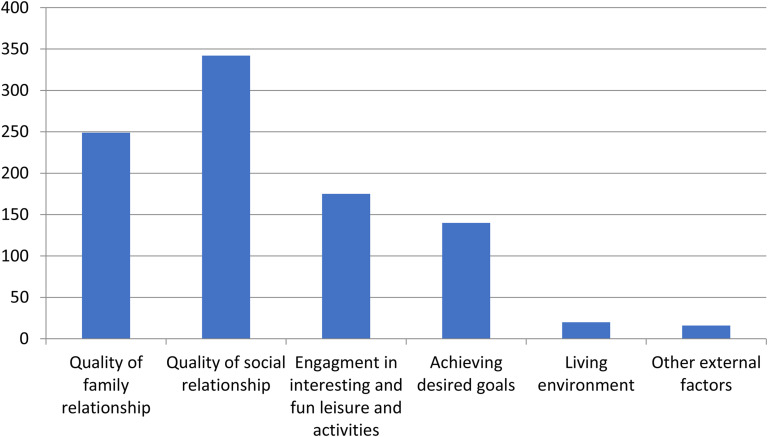

The results of thematic analysis in Figure 1 shows that children's LS can be defined within the following aspects: (1) Quality of social relationship; (2) Quality of family relationship; (3) Being engaged in interesting and fun leisure and activities; (4) Achieving desired goals; (5) Living environment; and 6) Other external factors.

Figure 1.

Domains specific of children's life satisfaction.

The data in Figure 1 indicates that with 342 answers, equivalent to 37.01% of the obtained answers, having a good social relationship is the most commonly found factor when children perceive themselves to be satisfied with life. The next commonly found themes are having a good family relationship and being engaged in interesting and fun leisure activities, respectively. In other words, when describing their LS, respondents in the study describe it in terms of intrapersonal relations, participation in specific activities, mostly doing interesting things, and attainment of their desired goals (e.g. good grades).

Thus, it can be seen that according to the respondents, two main aspects of life emerged as the most important LS dimensions are (a) The quality of social relationships, including relations with friends, teachers, being a good person, and being kind to others; and (b) The quality of family relationships.

Discussions

Our research finding revealed that most participants have the capability to interpret satisfaction as one's attitude towards life in general. This finding is entirely aligned with what Diener and colleagues4,34 found in their study, which is that satisfaction is conceptualized as reflective cognitive assessments of one's life. In line with previous studies, children in the present study reported their LS as complex and multidimensional11,35 and in the positive range.27,36,37

The importance of relationships with others

Our finding also implied that, in defining LS, children highly emphasize the importance of relationships with others, especially between peers and family members. The emphasis on quality relationships in children's perception of general well-being can also be found across many previous studies.25–27,38,39 Particularly, in our study, children emphasized the importance of social relations (including friends, peers, as well as teachers) as the most vital interpersonal resource for their LS. From the developmental psychology point of view, this finding is compatible with children's natural development at this age. During this stage of development, children focus not only on their studies but also on their relationships with peers. Throughout close friendships, children can freely express themselves, as well as give and receive feedback and support when needed. That is why positive peer relationships and friendships are very important for children in forming identity and personality. 40

Besides social relationships, relationships among family members also held a significant role in creating the perception of LS in children. As Do Long 41 has pointed out, in traditional Vietnamese culture, individual identity is not seen separately, but always in relation to a series of integrated systems that the individual belongs to. Children's focus on the relationship among family members can be seen as a specific domain of their LS. Although this conclusion has also been suggested in other studies on the topic (e.g.,27,42) it could also be explained based on the cultural-social reality in Vietnam. Accordingly, despite major changes in Vietnamese society, the family has always played an essential role in forming and developing Vietnamese children's personalities. The Vietnam proverbs such as “blood are thicker than water” (một giọt máu đào hơn ao nước lã), “brothers and sisters are as close as hands and feet” (anh em như thể tay chân) implies that the tradition of the close-knitted family has been embedded into the cultural fabrics of Vietnamese children and adults daily life philosophies. In fact, the family aspect has been recognized as a stable dimension of Vietnamese teenagers’ self-esteem through many previous studies.43,44 Furthermore, a recent qualitative study on happiness in the Vietnamese population at the early stage of adulthood suggested that positive relationships with other family members are also considered as one factor that brings happiness from the respondents' viewpoint. 24

Fun leisure and activities

Participation in leisure activities has been widely recognized as one of the fundamental human rights. 45 The previous study also pointed out that playtime and leisure activities are central parts of children's daily lives.46,47 It is through participation in such activities that children form friendships, develop skills, and experience enjoyment,48,49 thereby providing mechanisms for coping with life stress. 50 Therefore, it is not surprising that children in this study also report that besides social and family relationships, leisure time activities are also of considerable importance. Both family and school environments were considered core settings that reinforce children's socialization by forcing them to comply with certain sets of rules or codes of conduct. Thus, leisure activities in spare time were ideal opportunities for children's development of autonomy and competence needs since strict controls from their parents and teachers should be loosened, and they will be given more available space to act on their own. 51 Thereby, gaining autonomy in children's personal environments is achieved in part through leisure experiences. 50 However, from children's responses, it is evident that the leisure activities mentioned did not seem to relate to the process of identity construction. In other words, these activities were described simply as instruments to having fun.

It is also worth noticing that most children who participated in the study did not state learning at school as part of what they found satisfying in life. This finding could be understood through the general tendency in children to often find schools as obligatory and formal rather than a joyful and interesting environment. Therefore, apart from emphasizing social relationships created at schools (e.g. relationships with peers, teachers), children mainly focus on activities outside of school to satisfy them. As this trend was also found by Vujčić et al., 27 this study further consolidates their qualitative finding in this sample. According to these authors, young people often criticize the education system in terms of (a) its high workload and pressure; (b) difficulties in finding meaning and value in some school activities, and (c) the lack of opportunity to exercise their talents and work on their intrinsic goals. Our findings further broaden the idea that settings outside of school and family contexts, such as community-based and after-school activities, are also vital to the fulfillment of children's LS. 52 Several studies have shown that participation in these settings during middle childhood would anticipate positive academic achievements and emotional adjustment, and promote competence in several key developmental tasks, including school engagement, and social behaviors and relationships.53,54 It has been demonstrated that children involved in formal activities report significantly greater enjoyment than those who participated in unorganized and spontaneous activities. 55 In line with the finding, we agree that having extracurricular activities organized by the school such as sports, clubs, student newspaper, music, art, or drama are also essential to attain student's satisfaction. By spending a large proportion of their time at school with their teachers and peers, extracurricular would become a valuable resource to maintain children's LS and prevent them from involving in risky behaviors in the future. 56

Goals and living environment

From children's statements gathered in the study, it can be found that a considerable proportion of the children perceived LS occurs when they achieve their personal goals. This result could be seen as a positive signal in children's personality development and formation. The reason being those goals motivates actions; without goals, there are no actions. As Locke 57 suggested, “goals determine the direction, intensity, and duration of action” (p. 304).

Although children do not see the learning activities themselves as the source of LS, they did report finding it satisfying when they get high achievements in education. One way to explain this phenomenon can be through a historical-cultural perspective. In Vietnam, with the influence of Confucianism, Vietnamese people, children, in particular, have always attached great importance to education since ancient times. In fact, during some periods in history, education was considered the only way to success. Therefore, even though Vietnamese society has gone through many changes, most people still believe that their future depends on their learning outcomes at schools. Good academic results lead to a good future and vice versa. 44 Thus, culture could explain why children perceive their satisfaction mostly in connection with achieving their academic goals.

It is suggested that those who defined their LS based on their academic achievements but did not satisfy it could evoke a great deal of contradiction and frustration. Therefore, it is suggested that creating a positive classroom climate would help boost students’ morale and motivation to strive for better achievements. Baker et al. 58 asserted that “the sense of connectedness to others and support from the social environment are well-established correlates of resilience and contribute to numerous positive outcomes for children” (p. 211). Accordingly, emphasizing a child's strengths and promoting positive interactions and emotions in school serve to improve both individual performance and total school functioning, 59 thereby improving children's LS.

In addition to perceiving the achievements of life goals and dreams as times where they feel most satisfied, children also report dreaming about a good living environment as a factor in their perception of LS. However, different from previous findings where it has been suggested that living environment consists mainly of school facilities or family socioeconomic condition (e.g.,27,42) the participants in our study mentioned both their immediate surroundings and society as a whole. In this regard, children expressed their desire for a peaceful, developed society where there is no longer any natural disaster, poverty, or diseases and everyone lives happily. This is a positive signal in children's cognitive development because childhood and adolescence are considered dynamic and critical periods in one's development. While their learning of ecological worldview in formal schooling is often superficial and insufficient, 60 this result implies a positive and active aspect in children in exploring the world around them, contributing to building a great personality in this target group in the future.

Conclusion

The findings of the current study supported the research hypotheses and contributed to the existing literature by revealing how children understand satisfaction and what meanings they attach to. The present study has provided insights into how children understand and perceive LS. In general, most children see LS as positive and joyful expressions and often link it with their own experiences. These experiences are reported from this study's sample as strongly related to the quality of the most important relationships in their lives (including social and family relations), their engagement in meaningful and fun activities, and their pursuit of their desired goals. In other words, children feel satisfied when their important relationships are warm and supportive and when they have a sense of autonomy and agency in their lives.

However, this study has its own limitation. Although students at schools are diverse in social status, the utilization of convenient samples of Vietnamese students may limit the generalizability of the finding to the entire population. Thus, further research surveying different groups of Vietnamese children is important to validate the current research as well as in implementing a LS scale for children that is anchored in the Vietnamese culture. The present study is just an initial step in this direction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Editors and two anonymous Reviewers for their excellent suggestions for improving an earlier draft of the article.

Author biographies

Trinh Thi Linh received her PhD in 2010 at the University of Jean Jaurès (France). She is currently an Associated Professor at the Faculty of Psychology, University of Social Sciences and Humanities (VNU, Hanoi). Her research focused on issues of social/group psychology, positive psychology and developmental psychology. The list of her publications contains 40+ items in either English or Vietnamese, including books and research articles published in scientific journals.

Ngo Thi Hoang Giang is a senior lecturer at Ha Noi Open University. She holds a Bachelor degree in Social Studies, a Master of Arts in Psychology at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities (VNU-Hanoi), and is currently a PhD student in Psychology in this University. Her research interests include positive psychology, perceived happiness, life satisfaction, tourist behavior.

Truong Thi Khanh Ha, PhD, is an Associate Professor, Faculty of Psychology, VNU University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University, Hanoi. Her doctorate is from Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia in 2006. One of her research interest currently focuses on improving the Subjective Well-being of Vietnamese children and adolescents.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Vietnam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development (NAFOSTED) (grant number 501.01-2020.300).

ORCID iDs: Trinh Thi Linh https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4722-9852

Truong Thi Khanh Ha https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3940-8399

References

- 1.Diener E, Lucas RE, Oishi S. Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and life satisfaction. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ. (eds) The handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, pp.63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seligman MEP. Positive psychology, positive prevention, and positive therapy. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ. (eds) The handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, pp.3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. American Psycho 2000; 5: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas REet al. et al. Subjective well-being three decades of progress. Psychol Bull 1999; 125: 276–302. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fattore T, Mason J, Watson E. Locating the child centrally as subject in research: towards a child interpretation of well-being. Child Indic Res 2012; 5: 423–435. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Businaro N, Pons F, Albanese O. Do intelligence, intensity of felt emotions and emotional regulation have an impact on life satisfaction? A quali-quantitative study on subjective wellbeing with Italian children aged 8–11. Child Ind Res 2015; 8: 439–458. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Migliorini L, Tassara T, Rania N. A study of subjective well-being and life satisfaction in Italy: how are children doing at 8 years of Age? Child Ind Res 2019; 12: 49–69. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huebner ES, Diener C. Research of life satisfaction of children and youth: implications for the delivery of school-related services. In: Eid M, Larson R. (eds) The science of subjective well-being. New York: The Guilford Press, 2008, pp.376–392. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Camfield L, Tafere Y. “No, living well does not mean being rich”: diverse understandings of well-being among 11–13-year-old children in three Ethiopian communities. J Child Poverty 2009; 15: 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casas F. Children, adolescents and quality of life: the social sciences perspective over Two decades. In: Maggino F. (ed) A life devoted to quality of life. Social indicators research series, vol 60. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016b, pp.3–21. 10.1007/978-3-319-20568-7_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dex S, Hollingworth K. Children's and Young People's Voices on their Wellbeing . Childhood wellbeing research centre: Working Paper 2012; 16: 1–49. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/181515/CWRC-00108-2012.pdf (accessed 25 August 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spilsbury JC, Korbin JE, Coulton CJ. Mapping children's Neighborhood perceptions: implications for child indicators. Child Indic Res 2009; 2: 111–131. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor R, Olds T, Boshoff Ket al. et al. Children's conceptualization of the term “satisfaction”: relevance for measuring health outcomes. Child Care Health Dev 2010; 36: 663–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gross-Manos D, Shimoni E, Ben-Arieh A. Subjective well-being measures tested with 12-year-olds in Israel. Child Indic Res 2015; 8: 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilman R, Huebner ES. A review of life satisfaction research with children and adolescents. Sch Psychol Q 2003; 18: 192–205. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park N. The role of subjective well-being in positive youth development. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 2004; 591: 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proctor C, Alex Linley P, Maltby J. Youth life satisfaction measures: a review. J Posit Psychol 2009; 4: 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selin H, Davey G. (eds). Happiness across cultures: views of happiness and quality of life in non-western cultures. Heidelberg: Springer, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang L, Mcbride-Chang C, Stewart SMet al. et al. Life satisfaction, self-concept, and family relations in Chinese adolescents and children. Int J Behav Dev 2003; 27: 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau M, Bradshaw J. Material well-being, social relationships and Children's Overall life satisfaction in Hong Kong. Child Ind Res 2018; 11: 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park N. Life satisfaction Among Korean children and youth: a developmental perspective. Sch Psychol Int 2005; 26: 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou R, Niu G, Chen W, et al. Socioeconomic inequality and life satisfaction in late childhood and adolescence: a moderated mediation model. Soc Indic Res 2018; 136: 305–318. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol Rev 1991; 98: 224–253. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trinh LT, Khanh HT. Happy people: who are they? A pilot indigenous study on conceptualization of happiness in Vietnam. Health Psychol Rep 2019; 7: 296–304. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brindal E, Hendrie G, Thompson Ket al. et al. How do Australian junior primary school children perceive the concepts of healthy and unhealth? Health Educ 2012; 112: 406–420. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabhainn SN, Sixsmith J. Children's understandings of well-being. Galway: Department of Health Promotion, Centre for Health Promotion Studies, National University of Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vujčić MT, Brajša-Žganec A, Franc R. Children and young Peoples’ views on well-being: a qualitative study. Child Ind Res 2019; 12: 791–819. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denzin NK, Lincoln Y. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hennink M, Hutter I, Bailey A. Qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CAet al. et al. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 2015; 42: 533–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patton MQ. Qualitative research & evaluation methods: integrating theory and practice. 4th. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat Hum Behav 2018; 2: 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben-Arieh A, Casas F, Frones Iet al. et al. Multifaceted concept of child well-being. In: Ben-Arieh A, Casas F, Frones I, Korbin JE. (eds) Handbook of child well-being: theories, methodsand policies in global perspective. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2014, pp.1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huebner ES, Drane JW, Valois RF. Levels and demographic correlates of adolescent life satisfaction reports. Sch Psychol Int 2000; 21: 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung JP, Zhang L. Modelling life satisfaction of Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Int J Behav Dev 2000; 24: 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Diener E. The remarkable changes in the science of subjective well-being. Perspect Psychol Sci 2013; 8: 663–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian L, Chen H, Huebner ES. The longitudinal relationships between basic psychological needs satisfaction at school and school-related subjective well-being in adolescents. Soc Indic Res 2014; 119: 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Demir M, Özdemir M, Weitekamp LA. Looking to happy tomorrows with friends: best and close friendships as they predict happiness. J Happiness Stud 2006; 8: 243–271. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Do Long. La formation du “moi” chez l’enfant vietnamien sous l’influence de la culture [The formation of the “me” in the Vietnamese child under the influence of culture]. In: Lescarret O, Le K, Ricaud H. (eds) Actes du colloque «enfants, cultures, éducations» [proceedings of the conference “children, cultures, education”. Hanoi: Ed. du monde, 2000, pp.191–195. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huebner ES. Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life scale for children. Psychol Assess 1994; 6: 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dang HM. Orientation de soi chez les adolescents vietnamiens souffrant d’une maladie chronique: La dynamique entre l’estime de soi et la représentation de sa propre maladie . PhD Thesis, Université Toulouse II, Toulouse, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linh T, Huong T, Trang N. Development and validation of the self-esteem scale of toulouse (ETES) in Vietnam. Open J Soc Sci 2017; 5: 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- 45.UN. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. New York: United Nations, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bosse IK, Wetermann I. Inclusive leisure activities: necessary skills for professionals. An exploratory study. Int J Tech Incl Educ 2016; 5: 794–802. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ismael NT, Lawson LA, Cox JA. The relationship between children's Sensory processing pat terns and their leisure preferences and participation patterns. Can J Occup Ther 2015; 82: 316–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenblum S, Sachs D, Schreuer N. Reliability and validity of the Children's Leisure assessment scale. Am J Occup Ther 2010; 64: 633–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solish A, Perry A, Minnes P. Participation of children with and without disabilities in social, recreational and leisure activities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2010; 23: 226–236. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Majnemer A. Promoting participation in leisure activities: expanding role for pediatric therapists. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr 2009; 29: 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leversen I, Danielsen AG, Birkeland MS, et al. Basic psychological need satisfaction in leisure activities and Adolescents’ life satisfaction. J Youth Adolescence 2012; 41: 1588–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trilla J, Ayuste A, Agud I. After-School activities and leisure education. In: Ben-Arieh A, Casas F, Frones I, Korbin JE. (eds) Handbook of child well-being. Theories, methods and policies in global perspective. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2014, pp.863–894. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahoney JL, Larson RW, Eccles JS. (eds). Organized activities as contexts of development: extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Massoni E. Positive effects of extra curricular activities on students. ESSAI 2011; 9: 84–87. http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol9/iss1/27. Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 55.King G, Petrenchik T, Law Met al. et al. The enjoyment of formal and informal recreation and leisure activities: a comparison of school-aged children with and without physical disabilities. Intl J Disabil Dev Educ 2009; 56: 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Őnder FC, Yilmaz Y. The role of life satisfaction and parenting styles in predicting delinquent behaviors among high school students. Educational Science: Theory & Practice 2012; 12: 1744–1748. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Locke EA. Setting goals for life and happiness. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ. (eds) Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002, pp.299–312. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Baker JA, Dilly LJ, Aupperlee JLet al. et al. The developmental context of school satisfaction: schools as psychologically healthy environments. Sch Psychol Q 2003; 18: 206–221. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McCabe K, Bray MA, Kehle TJet al. et al. Promoting happiness and life satisfaction in school children. Can J Sch Psychol 2011; 26: 177–192. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoue M. Fostering an ecological worldview in children: rethinking children and nature in early childhood education from a Japanese perspective. In: Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles A, Malone K, Barratt Hacking E. (eds) Research handbook on childhoodnature. Springer international handbooks of education. Cham: Springer, 2020, pp.995–1024. [Google Scholar]