Abstract

Background:

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of childhood motor disability. However, there is limited guidance on training of child neurologists and neurodevelopmental disability specialists in the care of individuals with cerebral palsy. We sought to determine training program directors’ impressions of the importance and adequacy of training in the diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, all 82 child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability program directors were asked to complete a survey querying program characteristics, aspects of training in cerebral palsy, importance of cerebral palsy training, and perceived competence at graduation in cerebral palsy care.

Results:

There were 35 responses (43% response rate). Nearly all program directors (91%) reported “learning to diagnose cerebral palsy” as very important, and most (71%) felt that “learning to manage cerebral palsy” was very important. Although most program directors reported trainees to be very or extremely competent in cerebral palsy diagnosis (77%), only 43% of program directors felt that trainees were very or extremely competent in cerebral palsy management. Time spent with cerebral palsy faculty was associated with higher reported competence in cerebral palsy diagnosis (P = .03) and management (P < .01). The presence of a cerebral palsy clinic was associated with higher reported competence in cerebral palsy management (P = .03).

Conclusions:

Child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability program directors reported that training in cerebral palsy is important for residents; however, a significant proportion felt that residents were not very well prepared to manage cerebral palsy. The development of cerebral palsy curricula and exposure to cerebral palsy clinics may improve training, translating to better care of individuals with cerebral palsy.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, developmental disability, neurodevelopment, children, developmental delay, spasticity

Background

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common motor disability of childhood with an overall prevalence of approximately 2 of 1000 live births.1 It is one of the most common disorders a child neurologist or neurodevelopmental disabilities specialist will encounter.2 The precise role these specialists play in the care of the child with cerebral palsy may vary considerably depending on practice location. At one institution, they may direct the care of a child with cerebral palsy. At another institution, they may manage only the child’s epilepsy. Despite practice variability, child neurologists and neurodevelopmental disability specialists should have a minimum level of competence in this common neurologic disorder.

For child neurologists, such competencies are outlined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Child Neurology, which states that “child neurology involves the diagnosis, evaluation, and management of, and the advocacy for, infants, children, and adolescents with either primary or secondary disorders of peripheral and central nervous systems.”3 Although more than 20 areas of expertise such as epilepsy, stroke, headache, and neurotology are included in this document, there is no specific mention of cerebral palsy.

On the other hand, the ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities do address cerebral palsy, stating that “fellows must demonstrate knowledge in complicated management of diseases” including “cerebral palsy,” and that fellows must demonstrate competence in diagnosing and managing patients with neurodevelopmental disabilities, including “cerebral palsy.”4 Although neurodevelopmental disability training may be more focused on the care of individuals with cerebral palsy, there are only 8 such programs, inadequate to shoulder the responsibility alone. Child neurologists therefore must be adequately trained to care for these individuals.

Though cerebral palsy is an important and common disorder encountered by child neurologists and NDDs, there is little top-down guidance for programs to shape a cerebral palsy curriculum, which leads to inconsistency across programs. The objectives of this study are to assess child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability program director impressions of the importance and adequacy of training in the diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy, and to evaluate predictors of perceived resident competence in cerebral palsy diagnosis and management.

Materials and Methods

We conducted an online survey of all current program directors for the 74 child neurology and 8 neurodevelopmental disability training programs in the United States from February 2021 to June 2021. Participants were emailed a link to a REDCap electronic survey. Three reminder emails were sent. The survey was anonymous, although respondents could opt to report their state of residence and training program. A drawing for a $25 gift card was offered as incentive through an unlinked survey. The survey contained 43 items (see supplement). The survey queried program directors about cerebral palsy training in their program, including

Program information: Geographical location, institution, hospital type, number of child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability faculty

Program director details: years in position as a program director and subspecialty focus

Program faculty details: number of faculty and trainees and number of faculty with cerebral palsy expertise defined as “specific expertise or interest in caring for children with cerebral palsy”

Cerebral palsy training opportunities: frequency of cerebral palsy–related didactics, presence of cerebral palsy clinic, specialties in cerebral palsy clinic, requirement for trainees to attend cerebral palsy clinic, time spent with faculty with cerebral palsy expertise

Perceptions of training in cerebral palsy: importance of learning to diagnose and manage cerebral palsy, impressions of how well trainees learn to diagnose and manage cerebral palsy, perceived trainee competence at graduation in skills important in cerebral palsy care

Future directions: opinions on resources that would be helpful for trainees, impressions of the value of creating new subspecialty training programs in cerebral palsy

Standard descriptive analyses were used to describe results. We explored predictors of perceived resident competence in cerebral palsy diagnosis and management. The outcome variables were “How well does your training program prepare residents to diagnose cerebral palsy?” and “How well does your training program prepare residents to manage cerebral palsy?” Predictor variables were number of faculty, number of faculty with cerebral palsy expertise, time residents spent with cerebral palsy–expert faculty, presence of a cerebral palsy clinic, requirement to attend cerebral palsy clinic, and frequency of cerebral palsy didactics. Multiple-choice responses were collapsed to dichotomous variables given small cell sizes. For example, “not at all,” “slightly,” “moderately,” “very,” and “extremely” were collapsed into “not at all, slightly or moderately,” and “very or extremely.” Quantitative variables were analyzed as dichotomous variables. For example, number of faculty were categorized into <20 and ≥20. Fisher exact test was used to evaluate significance, as cell counts were predicted to be less than 5. Variables with missing data were noted. Analyses were performed using Stata, version 15.0 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools.

Results

Demographics

Complete survey responses were received from 42 program directors. We removed duplicate and associate program director responses, leaving a total of 35 responses, including 29 child neurology program directors (29/74 = 39% response rate) and 6 neurodevelopmental disability program directors (6/8 = 75% response rate), for an overall 43% response rate. There were 16 states and 21 programs represented, with 6 program directors not reporting their state and 12 program directors not identifying their program. Most (90%) child neurology program directors and all neurodevelopmental disability program directors reported having child neurology faculty with cerebral palsy expertise. Twenty (69%) child neurology programs and all neurodevelopmental disability programs reported access to a cerebral palsy clinic. Characteristics of the programs and program directors are shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Program and Program Director Characteristics.

| Child neurology, n (%) (n = 29) | Neurodevelopmental disabilities, n (%) (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Years as program directora | ||

| <5 | 10 (36) | 2 (33) |

| 5–9 | 9 (32) | 1 (17) |

| 10–14 | 4 (14) | 2 (33) |

| ≥15 | 5 (18) | 1 (17) |

| CN residents per yearb | ||

| ≤1 | 6 (21) | 3 (60) |

| 2 | 6 (21) | 0 |

| 3 | 8 (28) | 1 (20) |

| 4 | 3 (10) | 0 |

| ≥5 | 6 (21) | 1 (20) |

| NDD training program present | ||

| Yes | 5 (17) | |

| No | 24 (83) | n/a |

| Hospital type | ||

| Standalone pediatric | 20 (69) | 6 (100) |

| Pediatric within adult | 8 (28) | 0 |

| Other | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Program director subspecialtyc | ||

| Yes | 24 (83) | 6 (100) |

| No | 5 (17) | 0 |

| CN faculty | ||

| <10 | 5 (17) | 1 (17) |

| 10–19 | 10 (35) | 1 (17) |

| ≥20 | 14 (48) | 4 (67) |

| CN faculty with CP expertise | ||

| 0 | 3 (10) | 0 |

| 1–3 | 20 (69) | 3 (50) |

| ≥4 | 6 (21) | 3 (50) |

| NDD faculty | ||

| 0 | 16 (55) | 0 |

| 1–3 | 10 (35) | 0 |

| ≥4 | 3 (10) | 6 (100) |

| NDD faculty with CP expertise | ||

| 0 | 19 (66) | 0 |

| 1–3 | 10 (34) | 5 (83) |

| ≥4 | 0 | 1 (17) |

| Presence of a CP clinic | ||

| Yes | 20 (69) | 6 (100) |

| No | 9 (31) | 0 |

Abbreviations: CN, child neurology; CP, cerebral palsy, NDD, neurodevelopmental disability.

One missing child neurology program director response.

One missing neurodevelopmental disabilities program director response.

Reported subspecialties included neuromuscular and neuroimmunology (1), neurogenetics (1), stroke (1), neuroimmunology (1), headache (5), epilepsy (1), cerebral palsy (1), leukodystrophies (1), neurophysiology (1), neuromuscular (1) , epilepsy and neurodevelopment (1), and not reported (15).

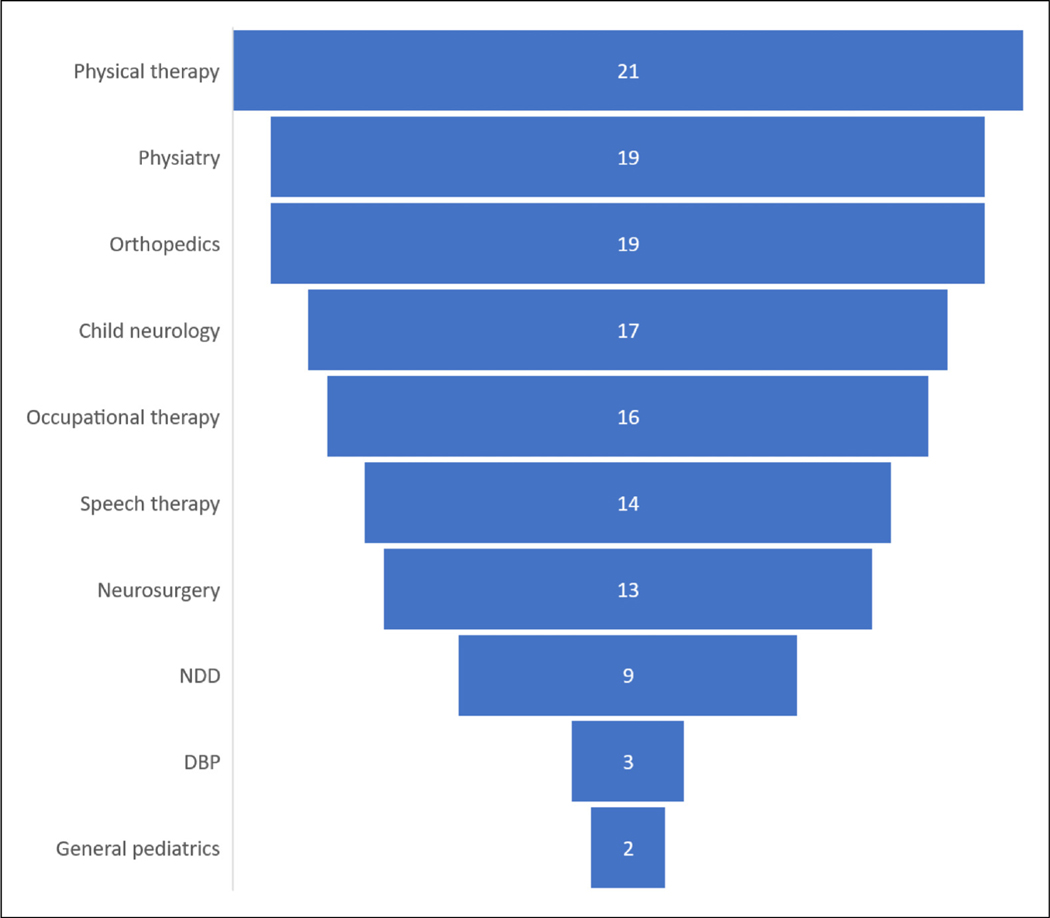

Specialty Involvement in Cerebral Palsy Management

We analyzed all responses for institutional characteristics, noting that all neurodevelopmental disability training programs are affiliated with a child neurology program within the same institution. Regarding cerebral palsy management, only 5 of 35 (14%) program directors reported that child neurology was the specialty that primarily manages cerebral palsy at their institution. More commonly, program directors reported that “various” subspecialists (n = 13, 37%), or physiatry (n = 13, 37%) primarily managed cerebral palsy. Of the programs with cerebral palsy clinics, the specialties present in the clinic are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cerebral palsy clinic providers. Number of program directors reporting the presence of each specialty in the multidisciplinary cerebral palsy clinic (total n = 26). Other reported specialties included orthotics (2), social work (2), and nutrition (1). Abbreviations: DBP, developmental and behavioral pediatrics; NDD, neurodevelopmental disability.

In contrast to an interdisciplinary approach, 9 program directors reported a more piecemeal, symptom-based care of children with cerebral palsy. Sample statements include the following:

Spasticity and dystonia go to [physiatry], seizures and developmental delay [to] neurology, both refer to physical therapy/occupational therapy/speech therapy.

Initial evaluations in child neurology, referral for spasticity to [physiatry] who offers Botox. We have one general neurologist, one neonatal neurologist, and one pediatric movement specialist who are all interested in CP.

Importance and Effectiveness of Cerebral Palsy Training

Almost all program directors (91%) rated “learning to diagnose cerebral palsy” as very important (26/29 child neurology and 6/6 neurodevelopmental disability). When asked about how well residents are trained in diagnosing cerebral palsy, most program directors (77%) reported residents were very or extremely well trained by the end of residency (23/29 child neurology and 4/6 neurodevelopmental disability). Most program directors (71%) also rated “learning to manage cerebral palsy” as very important (20/29 child neurology and 5/6 neurodevelopmental disability). However, only 43% of program directors reported residents being very or extremely well trained in cerebral palsy management by graduation (12/29 child neurology and 3/6 neurodevelopmental disability), indicating that cerebral palsy management is an area of relative weakness, with a gap between the current and ideal state of training (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Importance and competence in diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy. Left column: responses of program directors (top: child neurology, bottom: neurodevelopmental disabilities) to the question of importance of residents learning to diagnose (left bar) and manage (right bar) cerebral palsy. Right column: responses of program directors (top: child neurology, bottom: neurodevelopmental disabilities) to the question of how well their training program prepares residents to diagnose (left bar) and manage (right bar) cerebral palsy.

Despite 71% of program directors overall reporting that training in cerebral palsy management was very important, exposure to a dedicated cerebral palsy clinic was not a requisite part of training at many programs. Of the 20 child neurology programs with a cerebral palsy clinic, only 9 (45%) program directors required resident attendance, and 4 of the 6 (67%) neurodevelopmental disability program directors required resident cerebral palsy clinic attendance. All program directors reported trainees receiving some cerebral palsy didactics, with most (67%) program directors reporting 1 to 2 didactics per year (22/27; 2 missing responses). With regard to time spent with faculty with cerebral palsy expertise, the most common response among child neurology program directors was 1 to 2 weeks per year (n = 12, 41%), although one program director reported no time spent with such faculty and 3 (10%) reported less than 1 week per year. All neurodevelopmental disability program directors reported trainees engaging with these faculty 3 or more weeks per year.

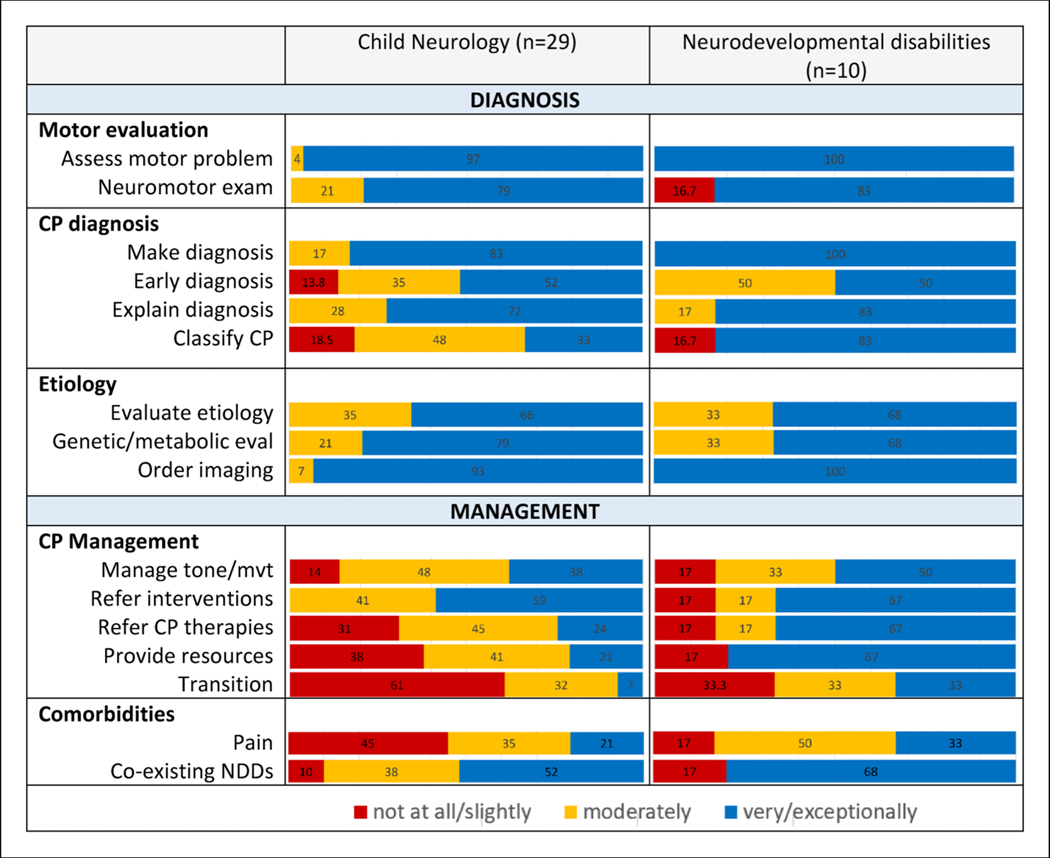

Cerebral Palsy Competencies

Program directors were asked to rate the level of competence of trainees by graduation on skills important in the care of children with cerebral palsy. Areas of perceived strength for child neurology residents (more than 75% of program directors reporting trainees to be very or exceptionally prepared) were assessing a child with a motor problem, the neuromotor examination, making a diagnosis of cerebral palsy, evaluating a genetic/metabolic cause, and ordering appropriate neuroimaging. Areas of perceived weakness for child neurology residents (more than 50% of program directors reporting trainees were not at all, slightly, or moderately prepared) included classifying cerebral palsy, managing tone/movement, referring for cerebral palsy–specific therapies, helping families navigate resources, transition to adult care, and pain management. Neurodevelopmental disability program directors generally reported similar patterns of strengths and weaknesses, although neurodevelopmental disability trainees were reported to be more competent in classifying cerebral palsy, referring for cerebral palsy–specific therapies, and helping families navigate resources (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reported competence at the end of training. Program directors’ reported level of resident competence at the end of training. Abbreviations: CP, cerebral palsy; eval, evaluation; mvt, movement; NDDs neurodevelopmental disability.

Time With Cerebral Palsy Faculty and Clinic Exposure Are Associated With Reported Competence in Cerebral Palsy Care

We explored predictors of reported trainee competence in diagnosing and managing cerebral palsy. Program directors with cerebral palsy clinics at their institution reported residents being better prepared to manage (but not diagnose) cerebral palsy (54% of programs with cerebral palsy clinics vs 11% of programs without cerebral palsy clinics reported trainees were very or extremely well trained in cerebral palsy management, P = .03). Program directors whose trainees spent more time with faculty with expertise in cerebral palsy reported their residents to be better prepared to diagnose (P = .03) and manage cerebral palsy (P < .01) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Time with faculty and reported cerebral palsy competence. Number of weeks per year residents spend with faculty with expertise in cerebral palsy and the percent of program directors reporting residents to be very or extremely well trained at graduation in diagnosis and management. *P = .03, ** P < .01.

The number of faculty in the program, number of cerebral palsy–expert faculty, requirement to attend cerebral palsy clinic, and the frequency of cerebral palsy didactics did not significantly predict reported trainee competence in diagnosing and managing cerebral palsy.

Program Directors Note That Centralized Guidance on Cerebral Palsy Didactics, Resources, and Literature Could Improve Cerebral Palsy Training

When asked what resources would be helpful, program directors most often felt it would be useful to have a suggested cerebral palsy curriculum (n = 31, 80%), followed by a list of seminal cerebral palsy articles (n = 28, 72%), web-based lectures series (n = 28, 72%), access to consolidated cerebral palsy resources (n = 27, 69%), and more cerebral palsy–related content at national meetings (n = 19, 49%). Fewer respondents felt it would be helpful to have more faculty (n = 14, 36%) and more access to clinics with children with cerebral palsy (n = 9, 23%). Additional free-typed suggestions included a full-day symposium/satellite preceding a national meeting (eg, Child Neurology Society) as is done for epilepsy.

Discussion

This is the first study to report on child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability program directors’ perceptions of training in cerebral palsy. We found that program directors nearly universally felt that training in diagnosis of cerebral palsy was very important, and that the management of cerebral palsy was important or very important. Although residents were generally felt to be well trained in cerebral palsy diagnosis, they were felt to be less prepared to manage cerebral palsy. Certain features of training programs correlated with better perceived training, such as spending more time with faculty with cerebral palsy expertise and the presence of a cerebral palsy clinic.

The child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability program directors’ emphasis on cerebral palsy diagnosis is consistent with the results of a recent survey of the CNS CP-SIG (Child Neurology Society cerebral palsy special interest group). The majority of these specialists (76%) felt that child neurologists should always be involved in the diagnosis of cerebral palsy.5 However, program directors reported less trainee competence in some diagnostic skills, such as making an early diagnosis of cerebral palsy, which is the current recommendation.6 Furthermore, although trainees were reported to be very competent in ordering neuroimaging, program directors reported slightly less competence in the overall evaluation of cerebral palsy etiology (one-third moderately competent, two-thirds very or extremely competent). This may reflect the complexity of cerebral palsy evaluation in some patients as genetic causes are becoming increasingly appreciated.7,8

Despite most program directors feeling that managing cerebral palsy was very important, they less often reported that residents were very well trained in management. In the same CP-SIG survey referenced earlier, half of specialists felt that child neurologists should only be involved in the management of cerebral palsy when certain neurologic comorbidities such as epilepsy were present.5 This may also be a reflection of the variability in systems of cerebral palsy care across institutions, where the child neurologists and neurodevelopmental disability specialists are centrally involved in some institutions and peripheral in others.

Looking at the specific skills of management, trainees were most commonly reported to be only moderately competent in tone and movement disorder management at the end of their training. This is consistent with a previous survey of child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability program directors in which 38% felt that residents would benefit from more training in spasticity management and 45% felt residents needed more training in movement disorders.9 Other areas in which residents were reported to be less competent included establishing an early diagnosis of cerebral palsy, transition to adult care, and pain management. These areas are often overlooked when caring for children with cerebral palsy and warrant further attention in training.

Neurodevelopmental disability program directors described similar patterns of strengths and weakness in training compared with child neurology program directors. However, there were some notable exceptions. Neurodevelopmental disability trainees were perceived to be better prepared to refer for cerebral palsy–specific therapies and guide families to resources. Still, neurodevelopmental disability trainees were also perceived to be less than ideally prepared in many areas of cerebral palsy management. Although neurodevelopmental disability graduates play an important role in the care of children with cerebral palsy, there are far too few neurodevelopmental disability graduates to entirely shoulder this responsibility.

Given inconsistent cerebral palsy training environments across programs, it is important to have top-down training guidance. As nearly all program directors feel cerebral palsy training is very important, this should be identified as a priority by the ACGME and individual programs themselves and should be reflected with cerebral palsy curricula. Web-based educational resources were requested by most program directors and could be an important way to provide consistent training despite institutional differences. We found that certain aspects of the programs, including spending more time with faculty with expertise in cerebral palsy and the presence of a cerebral palsy clinic, correlated with better perceived training outcomes, which may inform directions for improvement. When specifically asked, a minority of program directors felt that more faculty with cerebral palsy expertise and more access to cerebral palsy clinics would improve cerebral palsy training, which appears to contradict our finding of improved reported trainee competence at programs with these exact resources. It may be that program directors did not select this option because many already had adequate cerebral palsy faculty and cerebral palsy clinic exposure, or that adding specific faculty and creating a specialty clinic is not practical. A simple change would be a requirement that trainees attend cerebral palsy clinics at programs where these clinics are present, regardless of whether child neurology or neurodevelopmental disability specialists have a regular presence as attendings in the clinic. Programs without a dedicated cerebral palsy clinic should explicitly define the system of interdisciplinary care for children with cerebral palsy for their trainees, and specifically help their trainees find these experiences, even outside home institutions.

As there are no specific cerebral palsy training requirements, child neurology training may not be structured to meet the needs of individuals with cerebral palsy. In an earlier survey, more than 80% of recently graduated child neurology residents reported that a training program with fewer or no adult neurology months would have better prepared them to diagnose and manage cerebral palsy.10 Furthermore, children with cerebral palsy become adults with cerebral palsy, who continue to have very specialized needs, although it can be quite difficult to find adult neurology providers with cerebral palsy expertise.11 These gaps could be addressed in training, as adult neurology trainees rotate through pediatric neurology experiences.

This study has several limitations. As our results were anonymous, we could not validate the reported identities of all respondents. The responses may not be representative of all training programs, although response rates were similar to other survey-based studies.9,10 Selection bias may have skewed the results toward a greater importance/emphasis on cerebral palsy training as program directors more interested in cerebral palsy may have been more likely to respond. Furthermore, it is not clear how accurate program directors’ perceptions are with regard to the adequacy of training. To this end, a survey of child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability trainees was attempted along with this survey of program directors but suffered from a low response rate (10%). However, this trainee self-assessment reflected a similar pattern of reported strengths and weakness, lending some validity to the program directors’ responses and deserving future study. Despite the limitations, the results of this survey provide useful information for understanding the current state of child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability training in cerebral palsy.

Conclusion

Child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability program directors report that training in the diagnosis and management of cerebral palsy is important. Child neurology and neurodevelopmental disability trainees are felt to be well prepared to diagnose cerebral palsy, but they were not reported to be ideally competent in cerebral palsy management. Training programs would benefit from the development of a standardized cerebral palsy curriculum and facilitating access to cerebral palsy clinics and faculty with expertise in cerebral palsy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Peter Blasco, who assisted with survey development.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Oregon Health & Science University (no. 21555) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Oskoui M, Coutinho F, Dykeman J, Jetté N, Pringsheim T. An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(6):509–519. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirtz D, Thurman DJ, Gwinn-Hardy K, Mohamed M, Chaudhuri AR, Zalutsky R. How common are the “common” neurologic disorders? Neurology. 2007;68(5):326–337. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252807.38124.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Child Neurology. Updated July 1, 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/185_ChildNeurology_2021.pdf?ver=2021-06-22-171804-933

- 4.ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities. Updated July 1, 2021. Accessed July 8, 2021. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/186_NeurodevelopmentalDisabilities_2021.pdf?ver=2021-06-17-155016-583

- 5.Aravamuthan BR, Shevell M, Kim YM, et al. Role of child neurologists and neurodevelopmentalists in the diagnosis of cerebral palsy: a survey study. Neurology. 2020;95(21):962–972. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000011036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novak I, Morgan C, Adde L, et al. Early, accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):897–907. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jin SC, Lewis SA, Bakhtiari S, et al. Mutations disrupting neuritogenesis genes confer risk for cerebral palsy. Nat Genet. 2020;52(10):1046–1056. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno-De-Luca A, Millan F, Pesacreta DR, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in patients with cerebral palsy. JAMA. 2021;325(5):467–475. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valencia I, Feist TB, Gilbert DL. Program director survey: attitudes regarding child neurology training and testing. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;57:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert DL, Patterson MC, Pugh JA, Ridel KR, Reynolds TQ, Valencia I. Views of recently first-certified US child neurologists on their residency training. J Child Neurol. 2013;28(3):332–339. doi: 10.1177/0883073812473644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SE, Gannotti M, Hurvitz EA, et al. Adults with cerebral palsy require ongoing neurologic care: a systematic review. Ann Neurol. 2021;89(5):860–871. doi: 10.1002/ana.26040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.