Abstract

Aims

The variant p.Arg149Cys in ACTA2, which encodes smooth muscle cell (SMC)-specific α-actin, predisposes to thoracic aortic disease and early onset coronary artery disease in individuals without cardiovascular risk factors. This study investigated how this variant drives increased atherosclerosis.

Methods and results

Apoe−/− mice with and without the variant were fed a high-fat diet for 12 weeks, followed by evaluation of atherosclerotic plaque formation and single-cell transcriptomics analysis. SMCs explanted from Acta2R149C/+ and wildtype (WT) ascending aortas were used to investigate atherosclerosis-associated SMC phenotypic modulation. Hyperlipidemic Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice have a 2.5-fold increase in atherosclerotic plaque burden compared to Apoe−/− mice with no differences in serum lipid levels. At the cellular level, misfolding of the R149C α-actin activates heat shock factor 1, which increases endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis and intracellular cholesterol levels through increased HMG-CoA reductase (HMG-CoAR) expression and activity. The increased cellular cholesterol in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and activates PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling to drive atherosclerosis-associated phenotypic modulation in the absence of exogenous cholesterol, while WT cells require higher levels of exogenous cholesterol to drive phenotypic modulation. Treatment with the HMG-CoAR inhibitor pravastatin successfully reverses the increased atherosclerotic plaque burden in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice.

Conclusion

These data establish a novel mechanism by which a pathogenic missense variant in a smooth muscle-specific contractile protein predisposes to atherosclerosis in individuals without hypercholesterolemia or other risk factors. The results emphasize the role of increased intracellular cholesterol levels in driving SMC phenotypic modulation and atherosclerotic plaque burden.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, Smooth muscle cell, Smooth muscle α-actin, Phenotypic switching, Cholesterol

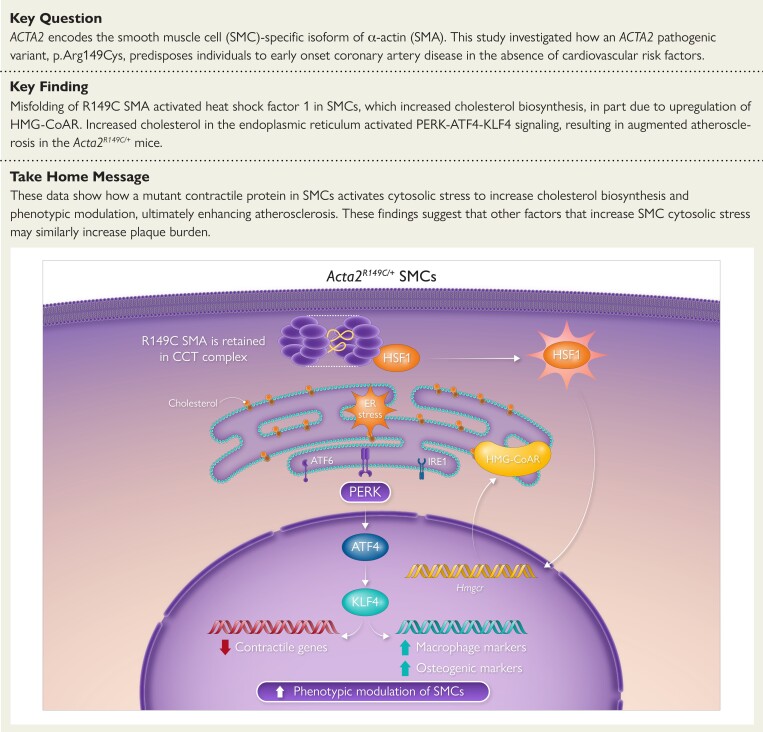

Structured Graphical Abstract

Structured Graphical Abstract.

Misfolding of Acta2 p.R149C activates heat shock factor 1 (HSF1), which in turn upregulates HMG-CoA reductase (HMG-CoAR) expression and activity, thereby increasing endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis. The increased levels of intracellular cholesterol induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, specifically activating the PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling axis, and lead to augmented smooth muscle cell (SMC) modulation in the absence of exogenous cholesterol in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs. CCT, chaperonin containing T-complex polypeptide-1; complex SMA, smooth muscle α-actin.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Statins for ACTA2 mutation-driven atherosclerosis?', by H. Zhang et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad364.

Translational perspective.

These results have direct implications for the management of individuals at risk for coronary artery disease who do not have hypercholesterolemia. Clinical trials have consistently shown that at-risk individuals with normal cholesterol levels benefit from statins but the reasons have remained unknown. Our results identify a molecular mechanism for atherosclerotic plaque formation in the absence of hypercholesterolemia and provide critical insight as to why statins prevent atherosclerosis in these at-risk individuals with normal cholesterol levels. These data make the case for using statins therapeutically in patients with ACTA2 variants in the absence of hypercholesterolemia.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic plaques leading to coronary artery disease (CAD) are a leading cause of death worldwide. Single-cell transcriptomic analyses (scRNA-seq) of aortas in hyperlipidemic mice have identified that smooth muscle cells (SMCs) undergo complex phenotypic modulation with plaque formation characterized by decreased expression of differentiation markers (e.g. Acta2, Cnn1) and variably increased expression of markers for stem cells (e.g. Ly6a), fibroblasts (Fn1, Ecrg4), macrophages (Lgals3), and chondrocyte-like cells (Spp1).1–4 SMC-specific deficiency of transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) in hyperlipidemic mice reduces plaque burden with loss of modulated SMC (mSMC) clusters that express macrophage and chondrocyte markers, indicating a role of KLF4 in SMC modulation.1,5 Cultured aortic SMCs exposed to free cholesterol or oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) recapitulate much of this phenotypic modulation due to cholesterol entering the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), triggering ER stress and an unfolded protein response (UPR).6 Of the three ER transmembrane receptors activated with UPR, double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK) is responsible for downstream activation of KLF4, de-differentiation of SMCs, and augmented expression of a subset of mSMC markers, including macrophage and chondrocyte markers.6 SMC-specific deletion of Perk in hyperlipidemic male mice reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation by up to 80% when compared to hyperlipidemic wildtype (WT) mice, illustrating the importance of exogenous cholesterol-induced PERK signaling in SMC modulation and plaque formation.7

Heterozygous pathogenic variants in ACTA2, which encodes the SMC-specific isoform of α-actin (SMA), predispose to thoracic aortic disease.8 Surprisingly, a recurrent pathogenic variant, ACTA2 p.Arg149Cys, predisposes to both thoracic aortic disease and premature onset of CAD in the absence of hypercholesterolemia or other risk factors.9 SMA monomer polymerizes to form thin filaments, a structural component of SMC contractile units, so the mechanistic link to augmented atherosclerosis is not readily apparent.10 All actins require interaction with the cytoplasmic chaperonin containing T-complex polypeptide-1 (CCT) complex to attain their native conformation, and actin monomers that cannot be properly folded remain bound to the complex.11 We previously showed that R149C SMA protein is misfolded and retained in the CCT complex in SMCs, whereas WT SMA is not.12 The Acta2R149C/+ mice do not develop thoracic aortic disease, and the retention of the mutant monomers in the CCT complex may minimize the effect of the mutant monomer on SMC contraction.12

Here, we show that Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice on a high-fat diet (HFD) have increased plaque burden when compared to similarly treated Apoe−/− mice despite comparable serum lipids, thus recapitulating the augmented atherosclerosis observed in patients with this pathogenic variant. Our data indicate that retention of R149C SMA in the CCT complex activates heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, which increases endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis by increasing HMG-CoA reductase (HMG-CoAR) expression and activity. Similar to exposure to exogenous cholesterol in WT SMCs, increased intracellular cholesterol levels in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs induce ER stress, thus activating PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling and SMC modulation in the absence of exogenous cholesterol. These studies identify the mechanism by which mutant R149C SMA triggers increased atherosclerotic burden, and further highlight the role of cholesterol-induced phenotypic modulation of SMCs in driving atherosclerotic plaque formation.

Methods

Generation of mouse models and treatment

Acta2R149C/+ mice were crossed into an Apoe−/− background (B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc/J, The Jackson Laboratory, strain #002052) and the resultant heterozygous mice were backcrossed with Apoe−/− mice to obtain Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice; Apoe−/− littermates were used as controls. To generate SMC lineage-traced mice, Apoe−/− or Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice were crossed with a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase driven by the SMC-specific Myh11 promoter [Myh11-CreERT2, B6.FVB-Tg(Myh11-icre/ERT2)1Soff/J, The Jackson Laboratory, strain #019079] with a floxed tdTomato (tdT) fluorescent reporter (B6.Cg-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm14(CAG-tdTomato)Hze/J, The Jackson Laboratory, strain #007914). The fluorescent reporter was induced by injecting the mice intraperitoneally with 1 mg tamoxifen/day for 10 days, starting at 6 weeks of age, for a total of 10 mg tamoxifen per 25 g body weight. At 6 weeks of age, Apoe−/− and Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice without lineage trace were placed on a HFD (Envigo, TD.88137) for 6 or 12 weeks as indicated in the specific experiments. WT and Acta2R149C/+ mice without hyperlipidemia were also treated with the same HFD for 12 weeks. SMC lineage-traced Apoe−/− and Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice were placed on HFD for 12 weeks starting at 8 weeks of age, at the end of the tamoxifen injection regimen. For pravastatin treatment, pravastatin was dissolved in drinking water at a final dose of 50 mg/kg body weight/day and the mice had ad libitum access to it. The drinking water containing the drug was replaced with a freshly prepared solution every 7 days. All animal studies were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines on the care and safety of laboratory animals.

Lipid profile analysis

At the end of the HFD regimen, the lipid profiles of the mice were analyzed by fast performance liquid chromatography at the Baylor College of Medicine Mouse Metabolism and Phenotyping Core (n = 7–8 mice per genotype, per sex unless mentioned otherwise), as described earlier.7

Analysis of plaque burden

Whole aortas were isolated from the experimental mice, cleaned, and then dissected longitudinally to expose the lumen. The tissues were then washed with 60% isopropanol for 30 s and then stained with Oil Red O solution (0.3% in 60% isopropanol) using standard protocols. Five to seven aortas were stained per genotype per sex in each experiment except for pravastatin treatment, where 8–10 male mice were used per genotype per treatment, since all female mice in both genotypes died prematurely during the pravastatin treatment. Sample sizes were chosen according to the recommendations of the American Heart Association.13 Analysis of plaque burden was performed in a blinded fashion by two researchers using ImageJ software and expressed as percentage area covered in plaque relative to the area of the entire aorta.

Histopathology

Aortic roots and ascending aortas from experimental mice were fixed in 10% formalin solution, embedded in paraffin and then cut into 5 μM sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard protocols, following which 5–10 randomly selected fields were imaged per sample using a Zeiss LSM800 microscope and quantified using ImageJ.

Immunofluorescent staining of aortic tissue

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded aortic sections from SMC lineage-traced mice were de-paraffinized, rehydrated, and then subjected to antigen retrieval using sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 98°C for 20 min. The tissues were then permeabilized with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.025% Triton X-100 and blocked for 1.5 h with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS. The sections were then incubated with either goat anti-SMA antibody (ab21027; Abcam) or rat anti-F4/80 (MF48000, ThermoFisher Scientific, clone BM8). Following overnight incubation at 4°C, the samples were washed with TBS containing 0.01% Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated with anti-goat or anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor™ 647 for 1 h at room temperature. The tissues were then washed again with TBST and mounted with ProLong™ Diamond Antifade Mountant (Invitrogen), following which the slides were allowed to dry for 24 h in the dark. Imaging was performed using a Nikon A1 Confocal Laser Microscope at the UTHealth Center for Advanced Microscopy. Negative control staining was performed using normal goat or normal rat IgG. Please refer to the Major Resources Table for detailed information on the primary antibodies used.

Single-cell transcriptomics

Tissues were isolated from the aortic root to the distal end of the aortic arch from four age-matched male SMC lineage-traced Apoe−/− or Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice, pooled together and digested to obtain single-cell suspensions, as described previously.7 Only male mice were used since the Myh11-CreERT2 gene is located on the Y-chromosome. Flow cytometry was used to detect and collect viable single cells. Barcoded cDNA was generated using a Chromium Single Cell 3′ v2 Reagent Kit (10× Genomics). This step was followed by cDNA amplification, truncation and library preparation. A NovaSeq 6000 Next Generation Sequencing system (Illumina) was used to perform sequencing at the Baylor College of Medicine Single Cell Genomics Core. As we described previously, the CellRanger Software (10× genomics) followed by the R package Seurat (V4.03) was used to analyze the sequencing data. The sequence of tdTomatoRed was added to the reference genome based on manufacturer’s instructions. Cells with high levels of mitochondrial genes (>10%) and <800 genes detected were removed. DoubletFinder was used to identify the doublets. After removal of doublets, we performed the integration on datasets normalized with SCTransform built into the Seurat pipeline. After merging datasets, we performed principal component analysis for dimensionality reduction. The selected principal components (Top 40) were used to create a shared nearest neighbor graph, on top of which, Louvain algorithm with multilevel refinement was applied to identify clusters. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection was used for visualization. Cell types were annotated manually by the expression pattern of marker genes. For SMC-derived cells, tdTomatoRed information was used as guidance. Marker gene expression, followed by enrichment analysis of the identified markers was used to identify SMC subtypes.

To identify the likelihood of cells that are most affected by Acta2 mutation, we used Manifold Enhancement of Latent Dimensions (MELD) to estimate density for every cell with SMC lineage; the ratio between the densities of each genotype provided the estimation of simulated likelihood.

We used R package Model-based Analysis of Single-cell Transcriptomics to detect differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between two groups of cells with the detection rate as a covariate. False discovery rate ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. For the DEGs, we ranked them by z-score, and performed pre-ranked gene-set analysis based on gene ontology annotations. P-values used to determine statistical significance were two-sided.

Evaluation of pathway-specific gene signatures

To evaluate activation levels of our pathways of interest, we defined signatures based on previous publications: PERK signaling signature (Eif2ak3, Eif2s1, Nfe2l2, Ppp1r15a, Atf4, Ddit3), SMC modulation signature (Lum, Dcn, Bgn, Fn1, Lgals3, C3, Tnfrsf11b, Spp1, Ly6a, Ibsp, Col2a1, Lcn2, Timp1), and HSF1 targets’ signature.3,7,14 For HSF1 targets, we selected the conserved targets from vertebrates to invertebrates and separated the genes by whether they are activated or inhibited by HSF1. UCell package was used to calculate gene signature scores.

Cellular treatment, RNA extraction and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR)

SMCs were explanted from the ascending aortas of Acta2+/+ and Acta2R149C/+ mice as described earlier and maintained in smooth muscle basal medium (SmBM, Promo Cell) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco), insulin, fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, HEPES (Millipore Sigma), sodium pyruvate (Millipore Sigma), L-glutamine, and 1% antibiotic/anti-mycotic (Millipore Sigma).15 Human cells were explanted from aortas of a patient with the ACTA2 R149H variant (25-year-old Caucasian male) and a healthy control (22 year-old male of unknown ethnicity) and maintained in SmBM supplemented with 10% FBS, insulin, fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and 1% antibiotic/anti-mycotic solution. Use of human cells was approved by and performed according to the policies set by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

For cholesterol and drug treatment, the cells were treated with indicated amounts of free cholesterol complexed to methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MBD-Chol, Millipore Sigma) in combination with indicated amounts of integrated stress response inhibitor (ISRIB) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or pravastatin (Millipore Sigma) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium containing high glucose (Cellgro), 10% FBS (Gibco), 1% antibiotic/anti-mycotic (Millipore Sigma), and 0.2% BSA (Fisher Scientific) for 72 h at 37°C and 5% CO2.

For heat shock studies, cells were treated at 44°C for 45 min in a water bath with 0.1°C accuracy and then allowed to recover for 12 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 before harvesting. For transactivation studies, cells were transfected with the reporter plasmid for ∼36 h, followed by heat shock as described above.

For RNA interference studies, SMCs were transfected with two separate Hsf1 siRNAs [Millipore Sigma, SASI_Mm01_00023056 and SASI_Mm01_00023057, abbreviated as si-HSF1(56) and si-HSF1(57), respectively] or scrambled siRNA (MISSION® siRNA Universal Negative Control #1, abbreviated as si-Scramble) using Lipofectamine reagent at a final concentration of 10 nM siRNA. Gene depletion was confirmed by qRT-PCR and immunoblotting.

PureLink RNA Mini kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was utilized to isolate total RNA, which was quantified using a Nanodrop instrument. This RNA was used to prepare cDNA using QScript reagent (Quantabio). Taqman chemistry was used for quantifying contractile gene transcripts (Applied Biosciences) and SYBR Green (Millipore Sigma) for all other genes using appropriate master mixes (Quantabio). Gapdh and 18S rRNA were used as internal controls for Taqman and SYBR reactions, respectively. Please refer to Supplementary data online, Table S1 in the Major Resources Table for primer sequences used for the SYBR reactions.

Acta2 variant expression in Acta2−/− cells

To stably express SM α-actin variants, variants were subcloned into the lentiviral vector pLVX-zsGreen1 (Clontech) and validated by Sanger sequencing. Lentivirus was packaged in 293T cells by co-transfecting the Acta2 constructs with packaging plasmids psPax2 and PMD2.G (Addgene) using lipofectamine transfection reagent (Life Technologies). Packaged virus was used to infect SMCs explanted from Acta2−/− mice with the addition of Polybrene (Millipore Sigma). Infection efficiency over 90% based on zsGreen1 expression was confirmed with Zoe Fluorescent Cell Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Immunoblotting

Explanted Acta2+/+ and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs were treated as indicated and then lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (all from Millipore Sigma). The proteins were quantified using Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories), resolved on 4%–20% TGX gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories), transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Sigma), blocked with 5% dry milk or 5% BSA in TBST, and incubated overnight with primary antibodies, followed by incubation with appropriate secondary antibodies. Bands were visualized by chemiluminescent substrate (GE Healthcare). Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software. Please refer to the Major Resources Table for detailed information on antibodies.

To detect R149C SMA on immunoblot, we lyzed the cells in urea buffer (110 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 200 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 20% glycerol and 8 M urea), cleared the lysate by centrifugation, mixed with SDS loading dye and resolved by SDS-PAGE as described above.

HMG-CoAR activity assay

HMG-CoAR activity assay kit (Abcam, ab204701) was used to estimate the HMG-CoAR activity in explanted Acta2+/+ and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly cells were lysed; the lysates were cleared by centrifugation and used for experiment. Protein concentration in the lysates was estimated using Bradford assay. Absorbance was measured in kinetic mode at 340 nm immediately after adding the reaction cocktail including reaction buffer, NADPH and HMG-CoA and the reaction was followed for 20 min, collecting readings every 2 min. Absorbance values at two time points in the linear range were used to calculate the enzyme activity per mg protein.

Cholesteryl ester formation assay

Cholesterol/Cholesteryl Ester Quantitation Assay kit (Colorimetric/Fluorometric, Abcam ab65359) was used to quantify cholesteryl ester formation in explanted SMCs. Briefly, cells were treated as indicated. Cells were harvested by trypsinization and collected by brief centrifugation. Pellets were suspended in a mixture of chloroform, isopropanol and detergent NP-40, vortexed and centrifuged to extract lipids. The organic phase was air dried at 50°C to remove the chloroform. The solid residue was used to perform a colorimetric assay to determine cholesteryl ester content according to manufacturer’s instructions. Total and free cholesterol concentrations were calculated using a standard curve and the difference between the two values was the cholesteryl ester concentration.

Luciferase activity assay

Explanted Acta2+/+ and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs were transfected with KLF4, ATF6, or HSF1 Cignal Reporter plasmid (Qiagen) and treated with indicated amounts of MBD-Chol for 72 h. Luciferase activity was analyzed using a Dual Luciferase Assay kit (Promega) and transcriptional activity was expressed as a ratio of firefly to internal Renilla chemiluminescence.

Transwell migration assay

We plated explanted Acta2+/+ and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs in the cell culture insert containing a permeable membrane, allowed cells to attach overnight, and then treated with MBD-Chol with or without ISRIB for 72 h. Following this incubation, we washed the cells with PBS, methanol, and distilled water and then stained them with NucBlue (Thermo Fisher Scientific). We excised the membranes containing the migrated cells and mounted them on glass slides. The cells were then imaged using filters for DAPI on a Zoe Fluorescent Cell Imager (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Migrated cells were quantified using ImageJ software.

Cellular proliferation assay

Explanted Acta2+/+ and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs were treated with MBD-Chol with or without ISRIB for 72 h. Analysis of proliferation was performed using a Click-iT™ Plus EdU Alexa Fluor™ 647 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 5 h prior to harvesting, 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) was added to the cells at a final concentration of 10 μM. The cells were harvested by trypsinization, following which they were fixed, permeabilized, incubated with EdU detection cocktail and then analyzed using flow cytometry.

Apoptosis assay

WT and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs were plated and treated with indicated amounts of MBD-Chol for 72 h. After harvesting, the cells were incubated in binding buffer containing apoptosis detection reagent from a GFP-CERTIFIED® Apoptosis/Necrosis Detection Kit (Enzo Life Sciences) for 5 min and analyzed immediately by flow cytometry.

Phagocytosis assay

WT and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs were plated on coverslips and treated with indicated amounts of MBD-Chol for 48 h, then FluoresbriteTM Plain YG 1 Micron Microspheres (Polysciences) was added to the media and the cells incubated for a further 24 h. The cells were washed, and the plasma membrane was stained with CytoPainter Cell Plasma Membrane Staining Solution (Abcam), then the cells were fixed, stained with DAPI and mounted on glass slides. The cells were then imaged using a Leica DMi8 SPE confocal microscope, using multiple randomly chosen fields. The number of fluorescent green dots within the cellular boundaries was counted in each image and divided by the number of nuclei in each image, to obtain the average number of phagocytosed particles per cell.

Statistical methods

All data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Data were tested for normality using GraphPad Prism software version 9.4.0 (Graph Pad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Comparisons between two groups were performed using unpaired student’s t-tests followed by Welch’s correction when the data passed normality, and Mann–Whitney U-test when they did not. For multiple group comparisons, analysis was performed using 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test when the data passed normality, and using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test when the data was not normally distributed. For lesion quantification by Oil Red O and H&E staining, each dot represents a single mouse. For quantification of immunostained tissue, each dot represents technical replicates (3–4) of aortic roots and ascending aortas obtained from 3 mice per genotype. All qPCR, immunoblotting, luciferase and enzyme activity data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. Points on the graphs represent technical replicates for cellular studies and image analysis, and biological replicates when describing quantification of aortic Oil Red O staining and lipid profile. Specific statistical tests used for each experiment are described in the figure legends.

Results

Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice have atherosclerotic plaque burden

Acta2R149C/+ mice were crossed into an Apoe−/− background and fed a HFD for 12 weeks, and atherosclerotic burden and plasma lipid levels were assessed. Oil Red O staining of the aortas found a 2.5-fold increased atherosclerotic burden in both male and female Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice compared with Apoe−/− mice (Figure 1A and B, Supplementary data online, Figure S1A). Analyses of aortic segments determined increased burden in the thoracic and abdominal aorta in the Acta2R149C/+ Apoe−/− mice but similar burden to the Apoe−/− mice in the aortic root, ascending, and arch region (Figure 1B). Since plaque burden was potentially maximized in the aortic root in these mice, plaque burden was assessed after only 6 weeks on a HFD, which confirmed greater plaque burden in the root and ascending aorta in the Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice compared with Apoe−/− mice (Figure 1C, Supplementary data online, Figure S1B). Furthermore, small plaques formed in the root and ascending aortas in Acta2R149C/+ mice with just 12 weeks of HFD in the absence of the Apoe−/− background but not in the WT (Apoe+/+) aortas (Figure 1D, see Supplementary data online, Figure S1C). Importantly, Acta2R149C/+ Apoe−/− mice had similar levels of total cholesterol, very-low-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), triglycerides, and high-density lipoprotein when compared to Apoe−/− mice after 12 weeks of HFD (see Supplementary data online, Figure S2A).

Figure 1.

Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice have increased atherosclerotic plaque burden. (A, B) Oil Red O staining shows Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice have increased atherosclerotic plaque burden in the whole, thoracic, and abdominal aortas, but not in the ascending aortas compared to Apoe−/− mice (n = 7 per genotype per sex, unpaired student’s t-test followed by Welch’s correction) after 12 weeks of HFD. (C, D) Plaque burden is greater in the roots and ascending aortas of Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice after 6 weeks of HFD (N = 5 per genotype per sex, Mann–Whitney test), (C), and in the same aortic regions of Acta2R149C/+ mice after 12 weeks of HFD, (N = 5 per genotype per sex, unpaired student’s t-test followed by Welch’s correction), (D). (E) Medial layers of both the roots and ascending aortas of Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice had significantly fewer tdTomato+ cells than those of Apoe−/− mice. (F) Cell density in the medial layers of the ascending aortas but not in the aortic roots is significantly lower in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice than Apoe−/− mice (N = 9, unpaired student’s t-test followed by Welch’s correction and Mann–Whitney test, respectively). Error bars represent standard deviation. *, **, ***, ****—P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively; ns—not significant.

Histopathological examination of aortic tissues in the Acta2R149C/+ Apoe−/− compared to Apoe−/− mice after 12 weeks of HFD revealed no difference in plaque area in the aortic roots, whereas the Acta2R149C/+ Apoe−/− ascending aortas did have significantly more plaque burden (see Supplementary data online, Figure S1D). These mice were bred into a tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase driven by the SMC-specific Myh11 promoter (Myh11-CreERT2) with a floxed tdTomato (tdT) fluorescent reporter, with tamoxifen injection at 5 weeks of age, to allow for SMC-lineage tracing during plaque formation. There were fewer tdTomato+ cells in the plaque and medial layer of the Acta2R149C/+ Apoe−/− aortic roots but more macrophages in the root plaques based on F4/80 staining compared to Apoe−/− aortas (Figure 1E, see Supplementary data online, Figure S1E and S2B). Medial cell density (nuclei/mm2) was lower in the ascending aorta but not the root of the Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− aortas compared to Apoe−/− aortas (Figure 1F).

Transcriptomic changes in the medial SMC clusters but not mSMC clusters in the aortas of the Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− when compared to Apoe−/− mice

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of aortic segments from the root to the distal aortic arch from SMC lineage-traced Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice after 12 weeks of a HFD revealed seven cell populations (Figure 2A, Supplementary data online, Figure S3A–I). The SMC-derived clusters were identified based on tdTomato expression and included a cluster with high expression of differentiation markers, designated as contractile SMCs (cSMCs), and two major mSMC clusters with decreased expression of SMC differentiation markers; one characterized by expression of inflammatory genes (e.g. C3, C4b; mSMCa), and the other by expression of mSMC markers (e.g. Spp1, Lum; mSMCb) (Figure 2B–D, Supplementary data online, Figure S4A–D). When perturbations in the SMC clusters induced by the presence of the mutant Acta2 allele were quantified at the single-cell level using MELD algorithm and Jensen–Shannon divergence, cSMCs showed the most significant transcriptomic changes between Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− aortas, and minimal differences were identified in the mSMC clusters (Figure 2E, Supplementary data online, Figure S4E and F). The cSMC cluster also had greater numbers of DEGs between the two genotypes than the mSMC clusters (Figure 2F). Genome wide association studies have identified >160 genomic loci associated with increased CAD risk in humans, and putative genes responsible for the signals at 38 of these loci were significantly differentially expressed in the cSMC cluster of Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− aortas compared to Apoe−/−, including increased expression of Klf4 (Table 1).14,16

Figure 2.

Single-cell transcriptomic analyses of Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− aortas: (A). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualization of all cell clusters obtained after scRNA-seq performed on tissue from the aortic root to the distal aortic arch of age-matched male SMC lineage-traced Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice (N = 4). (B) The distribution of SMC lineage reporter tdT expression across all cell clusters. (C) UMAP visualization and further clustering of SMCs into subtypes. (D) Top genetic markers identified for each subtype of SMCs. (E) Contractile SMCs show the highest difference in transcriptomic profiles between Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice when perturbations induced by a single point mutation in the Acta2 allele were quantified. (F) Differentially expressed genes across all subtypes of SMCs between the two genotypes. P-values used to determine statistical significance are all two-sided. cSMC—contractile SMC, mSMC—modulated SMC.

Table 1.

Putative genes at GWAS loci associated with coronary artery disease that were significantly differentially expressed in the cSMC cluster of Acta2R149C/+Apoe −/− aortas compared to Apoe −/−

| Terms | Number | Gene Names |

|---|---|---|

| GWAS hits up-regulated in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− cSMCs | 17 | Tcf21, Lmod1, Vegfa, Vamp8, Yy1, Stbd1, Tiparp, KIf4, Rpl17, Pde5a, Fign, Ddx5, Ldlr, Tns1, Irs1, Map3k1, Foxc1 |

| GWAS hits down-regulated in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− cSMCs | 21 | Tmed10, Daglb, Atp1b1, Lipa, Colgalt1, Fn1, Lox, Hhipl1, Fndc3b, Git1, Lrp1, Pltp, Rab23, Htra1, Ski, Wdr12, Slc22a4, Bmp1, Smad3, Pecam1, Cdh13 |

Augmented ER stress and phenotypic modulation in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs

To assess SMC phenotypic modulation in culture, Acta2R149C/+ and WT SMCs explanted from the ascending aortas of these mice were exposed to 0, 2.5, and 10 µg/mL of MBD-Chol for 72 h.6 Unexpectedly, Acta2R149C/+ SMCs had activation of all three UPR pathways at baseline: PERK activation was evident by increased phospho-eIF2α (P-eIF2α) levels, Atf4 and Klf4 expression, and increased KLF4 activity; Ire1α activation by increased spliced Xbp1 levels; and ATF6 activation by increased ATF6 cleavage and luciferase activity (Figure 3A–C, Supplementary data online, Figure S5A). In contrast, these UPR pathways were only activated in WT SMCs after exposure to 10 μg/mL MBD-Chol. Analyses of downstream gene targets of the three UPR pathways (Ddit3, Hspa5, and Edem) confirmed increased expression at baseline and with exposure to 2.5 µg/mL MBD-Chol in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, whereas the WT SMCs increased expression of these genes at 10 μg/mL MBD-Chol (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5B). A gene signature associated with PERK signaling was assessed in the SMC clusters from the scRNA-seq data, and the PERK signature was significantly increased in the three SMC-derived clusters in the Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− compared with the Apoe−/− aortas (Figure 3D).7

Figure 3.

Augmented ER stress and phenotypic modulation in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs. (A, B) Increased Atf4 and Klf4 expression and KLF4 luciferase activity (A), and increased levels of eIF2α phosphorylation, ATF4 and KLF4, (B), show baseline activation of PERK signaling in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs. (C) Increased splicing of Xbp1 (sXbp1/uXbp1) and ATF6 luciferase activity demonstrate activation of IRE1α and ATF6 signaling, respectively, at baseline in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs. (D) cSMCs, as well as both mSMC clusters in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− aortas showed significantly higher PERK signaling signature compared to Apoe−/− aortas. P-values used to determine statistical significance are all two-sided. (E) Baseline and MBD-Chol-driven increases in Atf4 and Klf4 expression, are reversed by treatment with the PERK pathway inhibitor ISRIB. Expression of Cnn1 is decreased and modulation markers Lgals3 and Spp1 are increased either at baseline or with exposure to 2.5 µg/mL MBD-Chol in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, compared to with 10 µg/mL MBD-Chol in WT SMCs. These changes are reversed with ISRIB. (F) Acta2R149C/+ SMCs showed both increased proliferation by EdU incorporation and migration by transwell migration assay at baseline and with cholesterol exposure, but only migration was blocked by ISRIB. All cellular data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Error bars represent standard deviation. *, **, ***, ****—P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively.

As expected with augmented PERK activation, Acta2R149C/+ SMCs had decreased expression of contractile genes and increased expression of atherosclerosis-associated modulation markers either at baseline or with exposure to 2.5 µg/mL MBD-Chol, whereas the WT SMCs did not similarly alter gene expression until exposure to 10 μg/mL MBD-Chol (Figure 3E, Supplementary data online, Figure S5C). Treatment with the PERK inhibitor, ISRIB, blocked the increased expression of Atf4 and Klf4, and the de-differentiation and increased expression of modulation markers in the Acta2R149C/+ SMCs when exposed to no or low levels of exogenous cholesterol, and also blocked these changes at 10 μg/mL MBD-Chol in the WT SMCs (Figure 3E, see Supplementary data online, Figure S5C).6 In contrast, Ly6a expression is increased in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs at baseline and its expression levels increase further with ISRIB treatment, whereas Ly6a expression is not affected by any of these treatments in the WT SMCs (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5C). Additionally, Acta2R149C/+ SMCs also demonstrated increased proliferation and migration at baseline when compared to WT SMCs, and migration was diminished with ISRIB treatment (Figure 3F, see Supplementary data online, Figure S5D). There were no differences between the WT and mutant SMCs in apoptosis assays; exposure to 10 μg/mL MBD-Chol induced apoptosis in both WT and Acta2R149C/+ SMCs (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5E). Finally, Acta2R149C/+ SMCs exhibited significantly higher phagocytic activity at baseline compared to WT SMCs, and the WT SMCs exhibited significant phagocytosis only at 10 μg/mL MBD-Chol (see Supplementary data online, Figure S5F).

Increased HSF1 activation drives PERK signaling in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs

HSF1 binds to the CCT complex, which folds actin and other cytosolic proteins, and can be activated with proteotoxic stress through phosphorylation (p-HSF1), followed by recruitment to heat shock elements on promoters of target chaperone genes.17 SMA with the R149C missense variant is misfolded and retained in the cytosolic CCT complex.12Acta2R149C/+ SMCs had increased levels of HSF1 and p-HSF1 at baseline, suggesting retention of the mutant SMA triggers cytosolic stress (Figure 4A, see Supplementary data online, Figures S6 and S7A). HSF1 luciferase activity and expression of HSF1 targets, Hspa1a, Hsp90aa1, Hsp90ab1, were also increased in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs at baseline but decreased with cholesterol exposure as Acta2 expression is suppressed (Figure 4B, see Supplementary data online, Figures S5C and S7B). Notably, p-HSF1 protein levels and activity also increase in the WT SMCs with exposure to 10 μg/mL MBD-Chol. Consistent with these findings, single-cell transcriptomic data showed a significant increase in an established HSF1 activation expression signature and a decrease in HSF1 inhibition signature in only the cSMC cluster in Acta2R149C/+ Apoe−/− aortas compared to Apoe−/− aortas (see Supplementary data online, Figure S4C).18

Figure 4.

Increased HSF1 activation drives PERK signaling in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs. (A) Acta2R149C/+ SMCs exhibit increased levels of total and phosphorylated HSF1 (p-HSF1) at baseline. (B) HSF1 luciferase activity and expression of HSF1 target Hspa1a are also upregulated at baseline in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs. (C) Single-cell transcriptomics reveal increased HSF1 activation gene expression signature and decreased HSF1 inhibition signature in the cSMC cluster of Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− aortas. P-values used to determine statistical significance are all two-sided. (D) In Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, siRNA-mediated depletion of Hsf1 reduces activation of the PERK pathway at baseline (Atf4 and Klf4 expression, along with KLF4 luciferase activity) as well as decreasing phenotypic modulation (increases Cnn1 expression and reduces Lgals3 and Spp1 expression). (E) Heatshock of WT SMCs increases HSF1 luciferase activity and expression of Hsf1 and its target Hsp90ab1, while simultaneously activating the PERK pathway (Atf4 and Klf4 expression and KLF4 luciferase activity) and inducing phenotypic modulation (decreased expression of Cnn1 and increased expression of Lgals3 and Spp1). All cellular data with cholesterol were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test and all heat shock data by unpaired student’s t-test followed by Welch’s correction. Error bars represent standard deviation. *, **, ***, ****—P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively.

Crosstalk between ER and cytosolic stress is well established and therefore, siRNAs were used to deplete HSF1 levels to determine if HSF1 activation drives PERK-ATF4-KLF4-dependent modulation in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs (see Supplementary data online, Figure S7C).19,20 In the Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, HSF1 deficiency decreases PERK signaling, based on decreased Atf4 and Klf4 expression and KLF4 activity and reverses the expression changes associated with SMC modulation (Figure 4D, see Supplementary data online, Figure S7D). HSF1 depletion did not alter Ly6a expression in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, and WT SMCs increased KLF4 activity with HSF1 depletion via an unidentified pathway (Figure 4D, see Supplementary data online, Figure S7D).

To further confirm that HSF1 activation drives UPR and PERK-ATF4-KLF4-driven SMC modulation in the absence of cholesterol, WT SMCs were heat shocked at 44°C for 45 min and allowed to recover at 37°C for 12 h. HSF1 activation by heat shock was confirmed through increased HSF1 activity and increased expression of Hsf1 and Hsp90ab1 (Figure 4E). Heat-shocked SMCs activated UPR and underwent modulation, as evident by upregulation of Atf4 and Klf4 expression and KLF4 activity, decreased expression of Cnn1, and increased expression of Lgals3 and Spp1 (Figure 4E, see Supplementary data online, Figure S7E).

HSF1 activation in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs increases HMG-CoAR levels and cellular cholesterol ester levels

HSF1 activation increases cholesterol biosynthesis, and intracellular cholesterol could drive increased UPR similar to exogenous cholesterol exposure.6,21 Therefore, we assessed the expression of genes encoding proteins in the cholesterol synthesis pathway, focusing on HMG-CoAR, the rate limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis.22 HMG-CoAR expression and activity, along with cholesterol ester levels, were increased at baseline in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs compared to WT, along with other genes involved in cholesterol biosynthesis (Figure 5A and B, see Supplementary data online, Figure S8A). Depletion of HSF1 using siRNAs decreased Hmgcr expression, HMG-CoAR activity, and cholesterol ester levels in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs (Figure 5C, see Supplementary data online, Figure S8B). Furthermore, heat shock of WT SMCs similarly increased Hmgcr expression, and Mvd expression (component in cholesterol biosynthesis pathway) (Figure 5D, see Supplementary data online, Figure S8C).

Figure 5.

HSF1 activation in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs increases HMG-CoA reductase levels. (A–C) Hmgcr expression is significantly elevated in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs (A), along with HMG-CoAR enzymatic activity and cholesteryl ester (CE) levels (B), which are both significantly reduced following siRNA-mediated depletion of Hsf1 (C). (D) Heat shocking WT SMCs also induces Hmgcr expression. (E) Treatment with the HMG-CoAR inhibitor pravastatin reduces baseline activation of the PERK pathway (Atf4 and Klf4 expression and KLF4 luciferase activity) and phenotypic modulation (decreased expression of Cnn1 and increased expression of Lgals3). (F, G) Treatment with pravastatin reduced plaque burden to similar levels in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice (N = 8 males). (H, I) SMCs explanted from an ACTA2 p.R149H patient demonstrated increased HSF1 and KLF4 activation at baseline, as well as increased expression of HMGCR and elevated levels of cholesteryl esters. Two-group comparisons were performed using unpaired student’s t-test, followed by Welch’s correction. Multiple group comparisons for both cellular and animal data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Error bars represent standard deviation. *, **, ***, ****—P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively. CE—cholesteryl ester.

To assess if the increased intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis is responsible for the augmented ER stress and phenotypic modulation of the Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, the HMG-CoAR inhibitor pravastatin was used. Exposure of the Acta2R149C/+ SMCs to 250 nM pravastatin decreased expression of Atf4 and Klf4 and KLF4 activity and prevented augmented phenotypic modulation (Figure 5E, see Supplementary data online, Figure S8D). To confirm increased HMG-CoAR activity was responsible for the augmented plaque burden in Acta2R149C/+ Apoe−/− mice, we treated male mice with pravastatin (50 mg/kg/day), which effectively lowered circulating serum lipid levels to a similar extent in both genotypes and prevented the increased plaque burden in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− male mice when compared to similarly treated Apoe−/− mice (Figure 5F and G, see Supplementary data online, Figure S8G).

To confirm similar cholesterol-driven augmented modulation occurs in a patient with this ACTA2 variant, we assessed SMCs explanted from a patient with ACTA2 p.R149H variant. These SMCs exhibited increased HSF1 expression and activity, HMG-CoAR expression, and cholesteryl ester formation at baseline (Figure 5H and I). ACTA2 p.R149H SMCs also had increased PERK-ATF4-KLF4 expression and activity, decreased expression of contractile markers (CNN1, ACTA2, TAGLN), and increased expression of LGALS3 and SPP1 both at baseline and/or with exposure to 2.5 μg/mL MBD-Chol when compared to age- and gender-matched control SMCs (see Supplementary data online, Figure S8E). Furthermore, HMG-CoAR activity was increased at baseline in the ACTA2 p.R149H SMCs compared with control SMCs (see Supplementary data online, Figure S8F).

Misfolding of the R149C SMA triggers HSF1 activation

We previously showed that R149C SMA is retained in the CCT complex but can be released from this complex when a second missense variant, N299T, is introduced into the monomer.12 We sought to confirm that misfolding of the R149C SMA in the CCT complex is responsible for HSF1 activation and downstream signaling.11,12 Four constructs (WT, R149C, N299T, and R149C with N299T) were inserted into a lentiviral vector and stably expressed in immortalized Acta2−/− SMCs. Despite transcript analyses demonstrating the constructs were expressed at similar levels, the R149C SMA monomer was not detectable on immunoblot analyses, whereas the R149C; N299T and N299T SMAs were present at levels comparable to WT (Figure 6A and B). Blocking protein degradation using either proteasomal or autophagy inhibitors did not identify the R149C SMA on immunoblot analyses, but low levels of the protein were identified when harsher lysis conditions were used, confirming the protein is translated (see Supplementary data online, Figure S9A). Expression of R149C SMA in the Acta2−/− SMCs induced HSF1 activation, increased HMG-CoAR expression and activity and cholesterol ester levels, and increased PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling and modulation of SMCs, whereas expression of R149C; N299T SMA did not (Figure 6C and D, see Supplementary data online, Figure S9B and C).

Figure 6.

Misfolding of the R149C SMA triggers HSF1 activation. (A, B) Despite expressing at similar transcript levels when expressed from a lentiviral construct in Acta2−/− SMCs (A), the R149C SMA monomer is not detectable on an immunoblot, while the WT, N299T, and R149C; N299T SMA monomers are (B). (C) Expression of R149C SMA leads to increased HSF1 activity, increased levels of cholesteryl esters, induction of Hmgcr expression and activity, and elevated KLF4 luciferase activity, which are all reversed by addition of the second point mutation, N299T. (D) Addition of the N299T mutation reverses the 2.5 µg/mL MBD-Chol-induced increased PERK activation (Atf4 and Klf4 levels) and augmented modulation (reduced Cnn1 expression and increased Lgals3 and Spp1 expression) caused by the R149C mutation alone. All cellular data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *, **, ***, ****—*P < 0.05, 0.01, 0.001, and 0.0001, respectively. CE—cholesteryl ester.

Discussion

We sought to determine how a rare missense variant in a gene encoding a SMC-specific contractile protein, ACTA2 p.R149C, increases the risk for premature CAD in the absence of elevated serum cholesterol levels or other risk factors. The novel cellular mechanism identified highlights a role of HSF1 activation and increased cholesterol biosynthesis in SMC phenotypic modulation and atherosclerotic plaque formation. Our data found that misfolding of the R149C SMA induces cytosolic stress mediated by HSF1, which increases HMG-CoAR levels and intracellular cholesterol biosynthesis. The increased cellular cholesterol levels activate ER stress and PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling, and augment atherosclerosis-associated SMC phenotypic modulation (Structured Graphical Abstract). In fact, we found that activating HSF1 signaling by heat shocking WT SMCs leads to similar increases in cholesterol biosynthesis and SMC phenotypic modulation. Previously, we identified that exogenous cholesterol exposure (MBD-Chol or oxLDL) drives ER stress, PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling and SMC modulation in WT SMCs.6 The importance of cholesterol-driven SMC phenotypic modulation was underscored by the fact that Perk deficiency in SMCs prevented 80% of plaque formation in male hyperlipidemic mice.7 The link from R149C SMA to augmented SMC modulation and plaque burden is similar, but rather than exogenous cholesterol driving the SMC modulation, increased biosynthesis of endogenous cholesterol is responsible for the enhanced SMC modulation. The importance of cholesterol-driven ER stress in SMC modulation aligns with the central role of the ER in sensing and regulating cholesterol homeostasis in cells and emphasizes the importance of this modulation of SMCs in augmenting plaque formation.23

Aspects of the pathway linking the R149C SMA to PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling have been implicated in plaque formation previously. Homocystinuria increases the risk of CAD and ischemic strokes.24 In hepatocytes and SMCs, homocysteine induces ER stress and an UPR, along with activation of the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) and increased expression of Hmgcr.25 These data suggest ER stress, driven by increased levels of homocysteine or cholesterol in SMCs, may contribute to augmented SMC modulation and increase the risk for atherosclerosis in individuals with homocystinuria. Additionally, cholesterol-driven ER stress has an established role in macrophage apoptosis associated with atherosclerotic plaque formation.26,27 Patients with Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome also have premature CAD without hyperlipidemia. This syndrome is due to pathogenic variants in LMNA that lead to production of a truncated protein, termed progerin. The production of progerin triggers ER stress in SMCs, and pharmacologic inhibition of ER stress reduces plaque burden in a mouse model of progeria, and similar to our findings, prevents medial SMC loss.28,29 Increased HSF1 activation has been previously implicated in atherosclerosis; analyses of rabbit atherosclerotic lesions identified increased levels of HSP90 and other targets, but the cell responsible for HSF1 activation was not delineated.30Hsf1 deletion in hyperlipidemic Ldlr−/− mice reduces atherosclerotic plaque burden but the defined mechanism was that blocking HSF1 activates cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) and increases multidrug transporter gene expression in the liver, which drives the decreased plaque burden.31 Finally, inducing heat-shock in Apoe−/− mice after plaque development promotes increased plaque formation but the mechanism was not defined.32

The Acta2R149C/+ SMCs express at least one atherosclerosis-associated modulation marker that is not dependent on HSF1 activation or increased cellular cholesterol—the stem cell marker Ly6a. Stem cell antigen 1, encoded by Ly6a, has been previously shown to promote cellular migration, and the higher expression of Ly6a in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs may contribute to the augmented migration in these cells.33Ly6a expression was previously shown to be KLF4-dependent.1,2,34 Here, we confirmed that Ly6a expression is not induced by exogenous cholesterol or blocked with PERK inhibition in either Acta2R149C/+ or WT SMCs. The sequence of the promoter of Klf4 gene contains heat shock elements, and evidence suggests that HSF1, like ATF4, transactivates KLF4.35,36Ly6a expression could therefore be driven by HSF1-KLF4 signaling that bypasses cholesterol- or UPR-driven modulation; however, deficiency of HSF1 in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs did not block Ly6a expression. Other cellular pathways that contribute to expression of specific SMC modulation markers, like Ly6a, and their role in plaque formation will require further investigation.

The Acta2R149C/+ SMCs demonstrated augmented phenotypic modulation, including increased proliferation, migration, de-differentiation, and heterogeneous increased expression of modulation markers, which raises the question as to which aspects of this augmented SMC modulation are responsible for the increased atherosclerotic plaque burden in the Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice. We previously found that deleting Perk from SMCs in hyperlipidemic mice significantly reduces plaque burden and prevents de-differentiation and loss of SMCs in the medial layer, but does not prevent these medial SMCs from accumulating cholesterol esters and increasing expression of modulation markers, suggesting that preventing PERK-driven SMC de-differentiation and migration are major contributors to the decreased plaque burden.7 This hypothesis is further supported by the fact that medial SMC loss is also prevented when plaque formation is inhibited by a drug that blocks ER stress in the progerin mouse model.28 Our single-cell transcriptomic analyses of the hyperlipidemic Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− vs. Apoe−/− aortas indicate that the most significant and extensive transcriptomic changes associated with the Acta2 mutation occur in the cSMCs cluster, whereas there were minimal differences in DEGs based on genotype among the mSMC clusters. Furthermore, these Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− aortas had fewer SMA+ medial SMCs than Apoe−/− aortas, suggesting increased medial SMC migration in the Acta2 mutant aortas. The lack of DEGs in the mSMC clusters between Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− aortas imply that after medial SMCs de-differentiate and migrate into the plaque, exogenous cholesterol may drive SMC modulation in both mouse models, thus minimizing the differences in expression of modulation markers between the mutant and WT SMCs.

One of the most widely prescribed class of drugs, statins, has an established role of inhibiting HMG-CoAR in the liver, decreasing cholesterol biosynthesis and increasing synthesis of LDL receptors, thus increasing LDL uptake from the blood and lowering serum LDL levels.22 Statins also significantly reduce CAD mortality in patients without elevated LDL levels, and elevated lipid levels are not entirely predictive of either CAD risk or efficacy of statins in preventing CAD.29,37,38 In Acta2R149C/+ SMCs, HSF1 activation increases HMG-CoAR and intracellular cholesterol levels, thus driving augmented SMC modulation, and statin treatment efficiently blocks the increased cholesterol biosynthesis and augmented modulation in these cells. Furthermore, pravastatin prevented the increased plaque burden in Acta2R149C/+Apoe−/− mice when compared to Apoe−/− mice. These data provide novel insight as to why statins are effective in individuals at risk for CAD who do not have hypercholesterolemia, and they provide a targeted therapy to decrease the risk for CAD in individuals with ACTA2 pathogenic variants. Further studies will decipher whether protein misfolding-induced cytosolic stress and HSF1 activation in SMCs is a common mechanism predisposing individuals to premature CAD in the absence of hypercholesterolemia.

Our data identify a novel mechanism by which a mutant SMC contractile protein, SMA, predisposes to early onset CAD in individuals without hypercholesterolemia. We show that misfolding of the ACTA2 pathogenic variant p.R149C activates HSF1, which in turn upregulates HMG-CoAR expression and activity, thereby increasing endogenous cholesterol biosynthesis. The increased levels of intracellular cholesterol induce ER stress, specifically activating the PERK-ATF4-KLF4 signaling axis, and lead to augmented SMC modulation in the absence of exogenous cholesterol in Acta2R149C/+ SMCs. Since SMA is almost exclusively expressed in SMCs, our data indicate that atherosclerosis burden can be driven by genetic variants in SMCs, specifically through augmenting SMC phenotypic modulation by inducing cytosolic stress and increasing intracellular cholesterol rather than exogenous cholesterol.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Kaveeta Kaw, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Abhijnan Chattopadhyay, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Pujun Guan, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Jiyuan Chen, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Suravi Majumder, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Xue-yan Duan, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Shuangtao Ma, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA; Department of Medicine, Michigan State University, 1355 Bogue St, B226B Life Sciences, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA.

Chen Zhang, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine, and Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Texas Heart Institute, 6770 Bertner Avenue, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Callie S Kwartler, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Dianna M Milewicz, Division of Medical Genetics, Department of Internal Medicine, McGovern Medical School, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, 6431 Fannin Street, Houston, TX 77030, USA.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at European Heart Journal online.

Declarations

Disclosure of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest for this contribution.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (RO1 HL146583 to D.M.M.) an America Heart Association Merit Award (to D.M.M.), NIH T32GM120011 (to K.K.), Marfan Foundation Victor A. McKusick Postdoctoral Fellowship Award (A.C.), and American Heart Association Grant 20CDA35310689 (C.S.K.). Lipid profile analysis was performed at the Mouse Metabolism and Phenotypic Core at the Baylor College of Medicine, funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) RO1DK114356 and UM1HG006348. scRNA-seq was performed at the Single Cell Genomics Core at Baylor College of Medicine, funded by National Institutes of Health shared instrument grants (S10OD023469, S10OD025240) and P30EY002520. Confocal microscopy was performed at the Center for Advanced Microscopy, a Nikon Center of Excellence, Department of Integrative Biology and Pharmacology at McGovern Medical School, UTHealth Houston.

Code Availability

All bioinformatics analyses were performed using freely available software and no custom codes were generated for this article. Single-cell RNA-sequencing data associated with this study are available from the SRA database under accession number PRJNA931298.

Materials Availability

Mouse strains and explanted SMCs will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and following completion of a materials transfer agreement.

References

- 1. Shankman LS, Gomez D, Cherepanova OA, Salmon M, Alencar GF, Haskins RM, et al. KLF4-dependent phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells has a key role in atherosclerotic plaque pathogenesis. Nat Med 2015;21:628–637. 10.1038/nm.3866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pan H, Xue C, Auerbach BJ, Fan J, Bashore AC, Cui J, et al. Single-cell genomics reveals a novel cell state during smooth muscle cell phenotypic switching and potential therapeutic targets for atherosclerosis in mouse and human. Circulation 2020;142:2060–2075. 10.1161/circulationaha.120.048378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wirka RC, Wagh D, Paik DT, Pjanic M, Nguyen T, Miller CL, et al. Atheroprotective roles of smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation and the TCF21 disease gene as revealed by single-cell analysis. Nat Med 2019;25:1280–1289. 10.1038/s41591-019-0512-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pustlauk W, Westhoff TH, Claeys L, Roch T, Geißler S, Babel N. Induced osteogenic differentiation of human smooth muscle cells as a model of vascular calcification. Sci Rep 2020;10:5951. 10.1038/s41598-020-62568-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alencar GF, Owsiany KM, Karnewar S, Sukhavasi K, Mocci G, Nguyen AT, et al. Stem cell pluripotency genes Klf4 and Oct4 regulate complex SMC phenotypic changes critical in late-stage atherosclerotic lesion pathogenesis. Circulation 2020;142:2045–2059. 10.1161/circulationaha.120.046672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chattopadhyay A, Kwartler CS, Kaw K, Li Y, Kaw A, Chen J, et al. Cholesterol-induced phenotypic modulation of smooth muscle cells to macrophage/fibroblast-like cells is driven by an unfolded protein response. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2021;41:302–316. 10.1161/atvbaha.120.315164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chattopadhyay A, Guan P, Majumder S, Kaw K, Zhou Z, Zhang C, et al. Preventing cholesterol-induced perk (protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase) signaling in smooth muscle cells blocks atherosclerotic plaque formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2022;42:1005–1022. 10.1161/atvbaha.121.317451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo DC, Pannu H, Tran-Fadulu V, Papke CL, Yu RK, Avidan N, et al. Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) lead to thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Nat Genet 2007;39:1488–1493. 10.1038/ng.2007.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guo DC, Papke CL, Tran-Fadulu V, Regalado ES, Avidan N, Johnson RJ, et al. Mutations in smooth muscle alpha-actin (ACTA2) cause coronary artery disease, stroke, and Moyamoya disease, along with thoracic aortic disease. Am J Hum Genet 2009;84:617–627. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fisher M, French S, Ji P, Kim RC. Cerebral microbleeds in the elderly: a pathological analysis. Stroke 2010;41:2782–2785. 10.1161/strokeaha.110.593657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Altschuler GM, Dekker C, McCormack EA, Morris EP, Klug DR, Willison KR. A single amino acid residue is responsible for species-specific incompatibility between CCT and alpha-actin. FEBS Lett 2009;583:782–786. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen J, Kaw K, Lu H, Fagnant PM, Chattopadhyay A, Duan XY, et al. Resistance of acta2(R149C/+) mice to aortic disease is associated with defective release of mutant smooth muscle α-actin from the chaperonin-containing TCP1 folding complex. J Biol Chem 2021;297:101228. 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Daugherty A, Tall AR, Daemen M, Falk E, Fisher EA, García-Cardeña G, et al. Recommendation on design, execution, and reporting of animal atherosclerosis studies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017;37:e131-e157. 10.1161/atv.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van der Harst P, Verweij N. Identification of 64 novel genetic loci provides an expanded view on the genetic architecture of coronary artery disease. Circ Res 2018;122:433–443. 10.1161/circresaha.117.312086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kwartler CS, Zhou P, Kuang S-Q, Duan X-Y, Gong L, Milewicz DM. Vascular smooth muscle cell isolation and culture from mouse aorta. Bio Protoc 2016;6:e2045. 10.21769/BioProtoc.2045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Erdmann J, Kessler T, Munoz Venegas L, Schunkert H. A decade of genome-wide association studies for coronary artery disease: the challenges ahead. Cardiovasc Res 2018;114:1241–1257. 10.1093/cvr/cvy084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neef DW, Jaeger AM, Gomez-Pastor R, Willmund F, Frydman J, Thiele DJ. A direct regulatory interaction between chaperonin TRiC and stress-responsive transcription factor HSF1. Cell Rep 2014;9:955–966. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kovács D, Sigmond T, Hotzi B, Bohár B, Fazekas D, Deák V. et al. et al. HSF1Base: a comprehensive database of HSF1 (heat shock factor 1) target genes. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20:5815. 10.3390/ijms20225815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roth DM, Hutt DM, Tong J, Bouchecareilh M, Wang N, Seeley T, et al. Modulation of the maladaptive stress response to manage diseases of protein folding. PLoS Biol 2014;12:e1001998. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim E, Sakata K, Liao FF. Bidirectional interplay of HSF1 degradation and UPR activation promotes tau hyperphosphorylation. PLoS Genet 2017;13:e1006849. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kang H, Oh T, Bahk YY, Kim GH, Kan SY, Shin DH, et al. HSF1 regulates mevalonate and cholesterol biosynthesis pathways. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1363. 10.3390/cancers11091363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science 1986;232:34–47. 10.1126/science.3513311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Röhrl C, Stangl H. Cholesterol metabolism-physiological regulation and pathophysiological deregulation by the endoplasmic reticulum. Wien Med Wochenschr 2018;168:280–285. 10.1007/s10354-018-0626-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eikelboom JW, Lonn E, Genest J Jr, Hankey G, Yusuf S. Homocyst(e)ine and cardiovascular disease: a critical review of the epidemiologic evidence. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131:363–375. 10.7326/0003-4819-131-5-199909070-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Werstuck GH, Lentz SR, Dayal S, Hossain GS, Sood SK, Shi YY, et al. Homocysteine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress causes dysregulation of the cholesterol and triglyceride biosynthetic pathways. J Clin Invest 2001;107:1263–1273. 10.1172/jci11596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feng B, Yao PM, Li Y, Devlin CM, Zhang D, Harding HP, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum is the site of cholesterol-induced cytotoxicity in macrophages. Nat Cell Biol 2003;5:781–792. 10.1038/ncb1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chung J, Kim KH, Lee SC, An SH, Kwon K. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) exerts anti-atherogenic effects by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress induced by disturbed flow. Mol Cells 2015;38:851–858. 10.14348/molcells.2015.0094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hamczyk MR, Villa-Bellosta R, Quesada V, Gonzalo P, Vidak S, Nevado RM, et al. Progerin accelerates atherosclerosis by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress in vascular smooth muscle cells. EMBO Mol Med 2019;11:e9736. 10.15252/emmm.201809736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gordon LB, Harten IA, Patti ME, Lichtenstein AH. Reduced adiponectin and HDL cholesterol without elevated C-reactive protein: clues to the biology of premature atherosclerosis in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. J Pediatr 2005;146:336–341. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.10.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Metzler B, Abia R, Ahmad M, Wernig F, Pachinger O, Hu Y, et al. Activation of heat shock transcription factor 1 in atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol 2003;162:1669–1676. 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64301-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krishnamurthy K, Glaser S, Alpini GD, Cardounel AJ, Liu Z, Ilangovan G. Heat shock factor-1 knockout enhances cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) and multidrug transporter (MDR1) gene expressions to attenuate atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 2016;111:74–83. 10.1093/cvr/cvw094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hashikawa N, Ido M, Morita Y, Hashikawa-Hobara N. Effects from the induction of heat shock proteins in a murine model due to progression of aortic atherosclerosis. Sci Rep 2021;11:7025. 10.1038/s41598-021-86601-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Batts TD, Machado HL, Zhang Y, Creighton CJ, Li Y, Rosen JM. Stem cell antigen-1 (sca-1) regulates mammary tumor development and cell migration. PLoS One 2011;6:e27841. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Worssam MD, Lambert J, Oc S, Taylor AL, Dobnikar L, Chappell J. Primed smooth muscle cells acting as first responder cells in disease. bioRxiv 2020:2020.2010.2019.345769. 10.1101/2020.10.19.345769 [DOI]

- 35. Liu Y, Wang J, Yi Y, Zhang H, Liu J, Liu M, et al. Induction of KLF4 in response to heat stress. Cell Stress Chaperones 2006;11:379–389. 10.1379/csc-210.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou AX, Wang X, Lin CS, Han J, Yong J, Nadolski MJ, et al. C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP) in vascular smooth muscle cells regulates their proliferation in aortic explants and atherosclerotic lesions. Circ Res 2015;116:1736–1743. 10.1161/circresaha.116.305602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fernández-Friera L, Fuster V, López-Melgar B, Oliva B, García-Ruiz JM, Mendiguren J, et al. Normal LDL-cholesterol levels are associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in the absence of risk factors. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2979–2991. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leeper NJ, Ardehali R, deGoma EM, Heidenreich PA. Statin use in patients with extremely low low-density lipoprotein levels is associated with improved survival. Circulation 2007;116:613–618. 10.1161/circulationaha.107.694117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.