Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer was estimated to be the second most diagnosed cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer mortality among men, with an estimated 1.4 million new cases and 375,000 deaths globally in 2020. There are significant changes in sexual activities and subsequent changes in quality of life associated with the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer. Sexual problems experienced by prostate cancer patients include erectile dysfunction, reduced sexual desire, reduced sexual function, problems with ejaculation, as well as problems with orgasm, and these could occur before and/or after treatment. This study aims to highlight the sexual characteristics of prostate cancer patients, which would help identify altered sexuality that might require intervention by healthcare providers.

Method

All patients who presented with pathologically diagnosed, organ-confined prostate cancer referred for high-dose-rate brachytherapy were approached for participation in the study. An interviewer-administered questionnaire was administered to the consenting patients.

Results

A total of 56 patients gave consent for the study out of 60. All the patients were married, with 5 (8.9%) having multiple wives. Only ten respondents (17.9%) reported having other sexual partners besides their wives. More than half of the patients (34) (60.7%) started having sexual intercourse between the ages of 18 and 20. Many patients claimed that the diagnosis of prostate cancer had affected their sexual lives. About half of the respondents (44.6%) believed that their partners were less satisfied with their sexual performance, as evidenced by the loss of partners (5.4%), partners refusing sexual advances (14.3%), partners complaints (10.7%), and partners' reduced inclination to ask for sex (33.9%). One patient expressed fears of passing the disease to their partners.

Conclusion

The management of prostate cancer should include sex therapy and rehabilitation in couples from the point of diagnosis to maintain sexual function as close as possible to that in the general population in order to maintain an improved quality of life.

Keywords: sexual characteristics, prostate cancer, sexual dysfunction

Introduction

Prostate cancer was estimated to be the second most diagnosed cancer and the fifth leading cause of cancer mortality among men, with an estimated 1.4 million new cases and 375,000 deaths globally in 2020 [1]. In Africa and Nigeria, prostate cancer was estimated to be the most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the leading cause of cancer mortality among men in 2020, with an estimated 93,173 new cases and 47,249 mortalities in Africa and 15,306 new cases and 8,517 mortalities in Nigeria [2, 3]. Nigeria accounted for 16.4% of the new prostate cancer cases and 18% of prostate cancer mortalities in Africa in 2020 [2, 3].

Incidence rates of prostate cancer vary across the world, with the lowest rates in Asia and Northern parts of Africa and the highest rates in The Caribbean, Europe, Australia, New Zealand, Northern America and Southern Africa, while prostate cancer mortality rates are highest in The Caribbean, Sub-Saharan Africa and Micronesia/Polynesia [1]. Some identified risk factors for prostate cancer include increasing age, genetic mutations, family history [1], blacks [4], smoking and being overweight [5].

There are significant changes in sexual activities and subsequent changes in quality of life associated with the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer [6]. Sexual problems experienced by prostate cancer patients include erectile dysfunction, reduced sexual desires, reduced sexual function, problems with ejaculation, as well as problems with orgasm, and these could occur before and/or after treatment [7–11]. Sexual dysfunction in prostate cancer patients could result from prostate cancer, prostate cancer treatments, and psychiatric disorders (such as depression, fear, anxiety and psychologic instability) resulting from prostate cancer diagnosis or its treatment [12–14].

Erectile dysfunction is the most extensively studied sexual dysfunction [15] and is defined as consistent or recurrent inability to attain and/or maintain penile erection sufficient for sexual activity by a man for ≥3 months [16]. Some studies have shown erectile dysfunction incidence post-radical prostatectomy to be between 20% and 90% [17–19]. Another study revealed the incidence of impotence in previously potent men as 65% after non-nerve-sparing prostatectomy, 58.6% after unilateral nerve-sparing prostatectomy, and 56.0% after bilateral nerve-sparing prostatectomy [20]. The incidence of erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy was reported to be 19%, 28%, 26% and 40% before radiotherapy, on the last day of radiotherapy, 2 months after radiotherapy, and 16 months after radiotherapy, respectively, with radiotherapy dose of 70.2–72Gy [21]. Following high-dose-rate brachytherapy, the incidence of erectile dysfunction was reported to be between 10% and 51%, with a median of 31.5% [22]. A meta-analysis that assessed the rate of erectile dysfunction after treatment for localised prostate cancer revealed the predicted probability of erectile dysfunction after high-dose-rate brachytherapy, external beam radiotherapy, high-dose-rate brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy, nerve-sparing prostatectomy, radical prostatectomy, and cryotherapy as 24%, 45%, 40%, 66%, 75% and 87%, respectively [23]. Other factors associated with erectile dysfunction include increasing age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and medications [24–26]. Changes in sexuality affect not only males with prostate cancer but also their partners [27] as both patients and their female partners suffer psychological effects of the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer [12, 28, 29].

Preservation of sexual function is important in the management of patients with localised prostate cancer [12] and health professionals need to keep this in mind to ensure better quality of life for prostate cancer patients and their partners [30]. This study aims to highlight the sexual characteristics of prostate cancer patients, which would help identify altered sexuality that might require intervention by healthcare providers. Also, this study will help fill some knowledge gaps, as studies on the sexuality of prostate cancer patients in Nigeria are sparse.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the study is to report on the sexual characteristics of the patients who presented with pathologically diagnosed prostate cancer.

Method

This study is a descriptive cross-sectional study carried out amongst pathologically confirmed, localised prostate cancer patients presenting at the Department of Radiation Oncology, University College Hospital, Ibadan, for high dose rate prostate brachytherapy between August 2020 and April 2022. The study questionnaire (Appendix 1) is made up of two sections administered to study participants with the help of a research assistant who helped in filling and translating medical terms in the study questionnaire for the ease of understanding of participants. All 60 patients seen within this period were approached for the study. However, only 56 patients gave written informed consent for the study. Data were collected from consenting patients with the aid of a questionnaire administered by the researchers. Other necessary clinical information was obtained from the patient’s case notes. The collected data was analysed using SPSS v. 22, and the results were presented in tables and frequencies.

Results

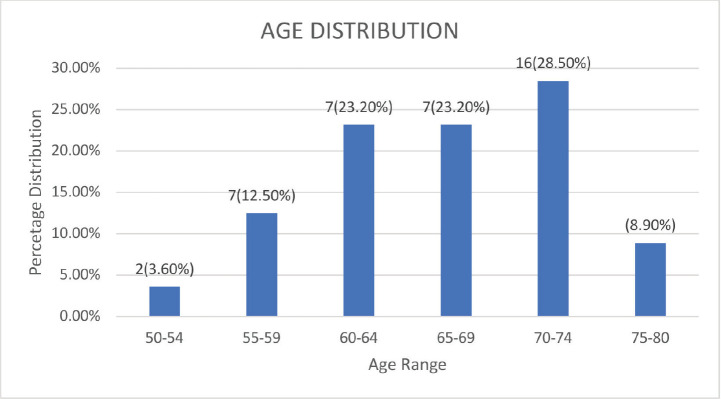

A total of 56 patients gave consent for the study out of 60 patients seen during the period. Their ages ranged from 51 to 79, with a mean age of 66.45 years and a SD of 6.785 (Figure 1). All patients had localised adenocarcinoma of the prostate, with prostate volume ranging between 23 and 96 mLs and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) ranging between 5.8 and 124.5 ng/mL, and were radiation treatment naïve. They all subsequently high dose brachytherapy 27 Gy in 2#. All the patients were married, with 5 (8.9%) having multiple wives. Only ten respondents (17.9%) reported having other sexual partners besides their wives. More than half of the patients (34%, or 60.7%) started having sexual intercourse between the ages of 18 and 20 years. The earliest was 15 (1 patient) years, while 37 years was the most advanced age for first sexual intercourse.

Figure 1. Age distribution of patients.

Most of the patients (91.1%) were sexually active prior to the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Only five patients (8.9%) were not sexually active before the diagnosis. Those who are not sexually active increased to 37.5% following the diagnosis (Table 1). Prior to diagnosis, most patients had sex once (20 patients, 35.7%) or twice (22 patients, 39.3%) per week.

Table 1. Occupation, Gleason score, sexual characteristics and sexual impact of prostate cancer diagnosis on patients.

| Occupation | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Retired | 30(53.6) |

| Trading | 6(10.7) |

| Medical doctor | 5(8.9) |

| Lecturer | 4(7.1) |

| Artisan | 4(7.1) |

| Businessman | 4(7.1) |

| Engineer | 3(5.4) |

| Gleason score | Frequency (%) |

| 3 + 3 | 24(42.8) |

| 3 + 4 | 20(35.7) |

| 4 + 3 | 5(8.9) |

| 5 + 3 | 2(3.6) |

| 5 + 4 | 3(5.4) |

| 5 + 5 | 2(3.6) |

| Sexual characteristics | Frequency (%) |

| Married | 56(100) |

| Polygamous | 5(8.9) |

| Other sexual partners | 10(17.9) |

| Sexually active before diagnosis | 51(91.1) |

| Sexually active after diagnosis | 35(62.5) |

| Use of sexual stimulants | 7(12.5) |

| Previous oral sex | 3(5.4) |

| Previous STD | 6(10.7) |

| Impact of prostate cancer diagnosis | Frequency (%) |

| Partner less satisfied | 25(44.6) |

| Decreased inclination for sex by partners | 19(33.9) |

| Partners' refusal of sexual advances | 8(14.3) |

| Complains about sex by partners | 6(10.7) |

| Partner left | 3(5.4) |

Only a few patients (7, 12.5%) reported using sex-enhancing substances like drugs and alcohol. Sildenafil and alcohol were the most popular substances used. Only three patients (5.4%) reported previous oral sex. Another 6 (10.7%) had a previous history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), some on multiple occasions. Gonorrhoea was the most commonly diagnosed STD. Others are staphylococcal and herpes infections. There was no history of syphilis among the patients.

Most of the patients knew their HIV status and that of their partners, and they all reported being HIV-negative.

Many patients claimed that the diagnosis of prostate cancer had affected their sexual lives. About half of the respondents (44.6%) believed that their partners were less satisfied with their sexual performance, as evidenced by the loss of partners (5.8%), partners refusing sexual advances (14.3%), partners' complaints (10.7%), and reduced inclination of the patients’ partners for sex (33.9%) (Table 1). One patient expressed fears of passing the disease to their partners.

Discussion

This study showed that the mean age of patients with prostate cancer presenting for brachytherapy was 66.45 years (SD: 6.785 years) and the ages ranged from 51 to 79 years. This finding is consistent with those from various studies globally and locally [1, 31–37]. This could be due to the increasing incidence of prostate cancer with increasing age [38]. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer in this age group could constitute additional morbidity, as patients within this age group are at increased risk of having other co-morbidities.

All patients in this study were married. This is similar to the findings of a study carried out in Lagos and another comparative study of clinicopathologic features between Nigerian patients in Abuja and South African patients with prostate cancer. In the Lagos study, all patients were either married (95.1%), separated (2.1%), or widowed (2.8%), while all patients from Nigeria in the comparative study were married [36, 37]. This could be due to sociocultural practices among Nigerians, as the proportion of married men increases with increasing age, as demonstrated by the 2018 national demographic health survey, which showed that over 90% of men between the ages of 40 and 49 were married [39].

Less than a tenth (8.9%) of the patients had multiple wives. The finding is slightly different from that of a study carried out amongst prostate cancer patients in Sokoto State, Nigeria, which showed that about 28.6% of patients were married in a polygamous setting [40]. This could be due to the predominance of Muslims in the Northern part of Nigeria, whose religion permits polygamy with a maximum of four wives [40]. Possible reasons for the preference for monogamy include religious, social and economic reasons [41].

In this study, 17.9% of the patients had sexual partners apart from their wife/wives. This finding is similar to the findings of a case-control study carried out in the United States of America, which showed that 27% of patients with prostate cancer have had sexual intercourse with prostitutes [42]. Extramarital affairs have been shown to have a significant association with younger age, urban residential areas, Yoruba ethnicity, early age of sexual debut, monogamy and higher levels of education [39, 43] and some of these factors could account for the findings in our study.

About three-fifths of the patients had their sexual debut between the ages of 18 and 20, with 15 years being the earliest and 37 years the latest. This finding is in tandem with studies carried out in the United States of America and Turkey, which demonstrated the age of first sexual intercourse among patients with prostate cancer to be 16–19 and 18 ± 6 years, respectively [42, 44]. This could be due to the existing sociocultural practices, as the median age of coitarche in the general population amongst men was revealed to be 21.7 years by the national demographic health survey in Nigeria [39]. Most pre-diagnosis sexual characteristics of patients in this study are almost similar to those of the general population, as shown by the national demographic health survey, and efforts should be made by the healthcare providers to ensure that the changes after diagnosis and treatment are as minimal as possible to ensure optimal quality of life.

The majority (91.1%) of the patients in this study were sexually active prior to diagnosis, and this proportion decreased to 62.5% after diagnosis. Findings similar to this were also made by Albaugh et al [45] who reported that the majority (74%) of the prostate cancer patients did not report erectile dysfunction prior to the diagnosis of prostate cancer while another study reported that 58.7% of patients were sexually active post-treatment [46]. The reduction in sexual activity could be due to factors such as the psychological trauma of diagnosis in both patients and partners, treatment, and the psychological stress of treatment [12–14, 28, 29]. Such a decrease in sexual activity can lead to decreased sexual satisfaction and a subsequent decrease in overall quality of life.

About 75% of the patients who were sexually active in this study had sexual intercourse at least once or twice per week, which is in tandem with the study carried out by Rousseau et al [47] where 80% of the prostate cancer patients had at least one sexual intercourse per week. The finding from this study is also similar to that carried out in the United States of America, which revealed that more than half of the patients with prostate cancer had sexual intercourse about 1–2 times per week [42].

Sex stimulants such as drugs (Sildenafil) and alcohol were used by patients (12.5%) in this study. Phosphodiesterase five inhibitors are part of the treatment options for the management of erectile dysfunction, with an 81% response rate following their use in prostate cancer patients with erectile dysfunction [48]. Alcohol, on the other hand, is seen by many as sex-enhancing, and this is ascribed to its disinhibitory properties [49]. Compared to the proportion of patients with reduced sexual activity, the proportion of patients that used sex enhancers was low, and this could be due to fear of drug interaction with treatment or under-reporting as a result of privacy concerns.

Three patients (5.4%) reported a prior history of oral sex. There is a dearth of literature relating to oral cancers in heterosexual prostate cancer patients. However, a study carried out among men who have sex with men revealed that oral sex was the most frequent form of sexual practice after masturbation [50]. Socio-cultural norms or the unpopularity of oral sex in Nigeria could account for the underreporting of oral sex practices in Nigeria. While there is no literature reporting an association between oral sex and prostate cancer, oral sex has been recommended as a form of sexual activity that can provide sexual pleasure and an avenue to build intimacy amongst partners [51].

Gonorrhoea was the most commonly reported sexually transmitted infection (STI) among 10.7% of patients who had a prior history of STIs. This is similar to a Mexican study that showed that 16.6% of the men reported previous STI, with gonorrhoea being the most common, and that a previous history of gonorrhoea was associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer [52]. The findings in this study were also in tandem with those from the case-control study done in the United States of America, which revealed that about 13% of patients with prostate cancer had a history of previous gonorrhoea infections [42]. Some studies have reported that age at first intercourse, number of sexual partners, and history of gonorrhoea may play a role in the aetiopathogenesis of prostate cancer, while others have demonstrated no association between the above sexual characteristics and prostate cancer [40, 42, 44, 53].

The diagnosis of prostate cancer was reported to affect the sexual lives of most patients. This could be due to psychological stress, fear and anxiety, resulting in altered sexual lives [12–14]. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer can also affect the sexuality of patients’ partners [12, 29–54], and in our study, 44.6% of patients believed that their partners were less satisfied sexually, which led to the reduced inclination for sex by patients partners (33.9%), refusal of sexual advances by patients partners (14.3%), complaints by patients partners (10.7%), and loss of a partner (5.4%). This brings to the fore a need by partners of patients with prostate cancer that needs to be catered for. Significant to note is that one patient’s sexual life was altered due to fear of transmitting prostate cancer to his partner. This highlights the need for proper patient education to prevent altered sexual function and a subsequent decrease in quality of life due to a lack of information.

This study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to evaluate the sexual characteristics of treatment-naive prostate cancer patients with localised disease in Nigeria. It is, however, limited by the sample size. Further analytical studies with a larger sample size need to be carried out to assess all aspects of sexual dysfunction in prostate cancer patients as well as their partners for prompt pre-emptive management to ensure improved quality of life for prostate cancer patients and their partners.

Conclusion

Prostate cancer is a disease of public health importance due to its burden on society. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer have a significant impact on the sexuality of prostate cancer patients and their partners, with a subsequent impact on their quality of life. Thus, the management of prostate cancer should include sex therapy and rehabilitation in couples from the point of diagnosis to maintain sexual function as close as possible to that in the general population in order to maintain an improved quality of life.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed on the publication of this manuscript.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Ethical consideration

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University College Hospital Ibadan.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Appendix 1. Questionnaire.

Section A: Sociodemographic data

Study center: ____________________ Year of study ___________________

Age:______ Religion:____________ Tribe:____________ State (Origin):____________ State (Residencial)____________ Occupation: ____________

Marital Status: Single ( ) Married ( ) Separated ( ) Divorced ( ) Widow ( ) Co-habiting( ) Others

Section B: Clinical characteristics

Past history Hypertension ( ) Diabetes ( ) Seizures ( ) Asthma ( )

Others (specify) ___________________Drug history: _____________________________ Previous surgeries: _______________________________

PSA:

Histologic type:___________________

Perineural invasion: Yes ( ) No ( )Lymphovascular invasion Yes ( ) No ( )

Gleason score

Grade

Stage

Nature of specimen: Transrectal ( ) Transurethral ( ) Transperineal ( )

Prior hormone therapy and duration.

Prior EBRT (Dose, Fractionation, Dose Per Fraction Duration and Facility).

Prior chemotherapy (regimen and duration)

Brachytherapy (Dose, Fractionation, Dose/Fraction and Duration)

EBRT after brachytherapy (Dose, Fractionation, Dose/Fraction, Duration, Facility)

Section B: Sexual characteristics

Multiple wives: Yes ( ) No ( ) No of wives: ____________

Other sexual partners: Yes ( ) No ( ) No of sexual partners: ________

Age at first sexual intercourse? __________

Do you consider yourself sexually active before this diagnosis?Yes ( ) No ( )

Do you consider yourself sexually active after this diagnosis?Yes ( ) No ( )

How often do you have sex in 1 week/month: ____/Week or ____/Month

Have you ever used sexual aid like drug/alcohol?

List them: ______________________________________________

Have you ever had oral sex performed on you before? Yes( ) No( ) How often?____

Previous history of sexually transmitted disease? Yes( )No ( ) How many times?____

Do you know the diagnosis? Yes( ) No( ) List___________________

Do you know your HIV status? Yes( ) No( ) Negative or Positive _________

If positive, are you on treatment? Yes ( ) No ( )

Do you know your partners’ HIV status?Yes ( ) No ( ). Negative ( ) Positive ( )

Do you think your partner(s) are often satisfied with your performance?

Partner(s) left ( ),

Partner(s) less inclined to ask for sex ( ),

I am less inclined to ask for sex ( ),

My performance has diminished ( ),

Partner(s) complaining ( ),

Partner(s) and I have fears of passing on the disease ( )

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research in Africa Global Cancer Observatory. [ https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/903-africa-fact-sheets.pdf]

- 3.International Agency for Research, Nigeria Global Cancer Observatory. [ https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/populations/566-nigeria-fact-sheets.pdf]

- 4.Rebbeck TR, Devesa SS, Chang BL, et al. Global patterns of prostate cancer incidence, aggressiveness, and mortality in men of African descent. Prostate Cancer. 2013;2013:560857. doi: 10.1155/2013/560857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for cancer research continuous update project expert report 2018 body fat, weight gain, and the risk of cancer. [27/10/20]. [dietandcancerreport.org]

- 6.Benedict C, Traeger L, Dahn J, et al. Sexual bother in men with advanced prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. J Sex Med. 2014;11(10):2571–2580. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hald GM, Pind MD, Borre M, et al. Scandinavian prostate cancer patients’ sexual problems and satisfaction with their sex life following anti-cancer treatment. Sex Med. 2018;6(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saitz TR, Serefoglu EC, Trost LW, et al. The pre-treatment prevalence and types of sexual dysfunction among patients diagnosed with prostate cancer. Andrology. 2013;1:859–863. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott S, Matthew A. Sexual recovery following prostate cancer: recommendations from two established Canadian sexual rehabilitation clinics. Sex Med Rev. 2018;6:279–294. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushita K, Tal R, Mulhall JP. The evolution of orgasmic pain (dysorgasmia) following radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2012;9:1454–1458. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fode M, Snksen J. Sexual function in elderly men receiving androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) Sex Med Rev. 2014;2(1):36–46. doi: 10.1002/smrj.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyun JS. Prostate cancer and sexual function. World J Mens Health. 2012;30(2):99–107. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2012.30.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore TM, Strauss JL, Herman S, et al. Erectile dysfunction in early, middle, and late adulthood: symptom patterns and psychosocial correlates. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29:381–399. doi: 10.1080/00926230390224756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ. The association between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms in men treated for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8:560–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benson CR, Serefoglu EC, Hellstrom WJG. Sexual dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. J Androl. 2012;33:1143–1154. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.112.016790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dwyer M, Nehra A. Defining sexual function after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Urol Oncol. 2010;28:469–472. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litwin MS, Lubeck DP, Henning JM, et al. Differences in urologist and patient assessments of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer: results of the CaPSURE database. J Urol. 1998;159:1988–1992. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawanishi Y, Lee KS, Kimura K, et al. Effect of radical retropubic prostatectomy on erectile function, evaluated before and after surgery using color doppler ultrasonography and nocturnal penile tumescence monitoring. BJU Int. 2001;88:244–247. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel T, Moul JW, Spevak M, et al. The development of erectile dysfunction in men treated for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2001;165:430–435. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. JAMA. 2000;283(3):354–360. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinkawa M, Gagel B, Piroth MD, et al. Erectile dysfunction after external beam radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;55(1):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Challapalli A, Jones E, Harvey C, et al. High-dose rate prostate brachytherapy: an overview of the rationale, experience, and emerging applications in the treatment of prostate cancer. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1):S18–S27. doi: 10.1259/bjr/15403217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JW, Moritz S, Fung T. Meta-analysis of rates of erectile function after treatment of localized prostate carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54(4):1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(02)03030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schouten BWV, Bohnen AM, Groenerveld FPMJ, et al. Erectile dysfunction in the community: trends over time in incidence, prevalence, and medicine use. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2547–2553. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montejo AL, Llorca G, Izquierdo JA, et al. Incidence of sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant agents: a prospective multicenter study of 1022 outpatients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werneke U, Northey S, Bhugra D. Antidepressants and sexual dysfunction. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:384–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grondhuis Palacios LA, Krouwel EM, Oudsten BL, et al. Suitable sexual health care, according to men with prostate cancer and their partners. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(12):4169–4176. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4290-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamilton LD, Van Dam D, Wassersug RJ. The perspective of prostate cancer patients and patients’ partners on the psychological burden of androgen deprivation and the dyadic adjustment of prostate cancer couples. Psycho-Oncology. 2015;25:823–831. doi: 10.1002/pon.3930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kornblith AB, Herr HW, Ofman US, et al. Quality of life of patients with prostate cancer and their spouses. The value of a database in clinical care. Cancer. 1994;73:2791–2802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::AID-CNCR2820731123>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joana T, Germano C, Ana P, et al. Sexual dysfunction and quality of life in prostate cancer. 2020;43(1):218. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hathout L, Mahmoud O, Wang Y, et al. A phase 2 randomized pilot study comparing high-dose rate brachytherapy and low-dose-rate brachytherapy as monotherapy in localized prostate cancer. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2019;4:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2019.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, Sesterhenn IA, editors. tumors of the prostate. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oluwole OP, Rafindadi AH, Shehu MS, et al. A ten-year study of prostate cancer specimens at Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital (A.B.U.T.H. ), Zaria, Nigeria. Afr J Urol. 2015;21:5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.afju.2014.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emiogun FE, Williams OO, Obafunwa JO. Epidemiology of prostate cancer in Nigeria: observations at Lagos State University Teaching Hospital. Cancer Health Disparities. 2019;4:e1–e9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ajape AA, Ibrahim KO, Fakeye JA, et al. An overview of prostate cancer diagnosis and management in Nigeria: the experience in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Ann Afr Med. 2010;9(3):113–117. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.68353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adewumi AO, Anthonia SC, Alabi AS, et al. Pattern of prostate cancer among a Nigerian population: a study in a single tertiary care centre. Niger J Med. 2016;25(1):70–76. doi: 10.4103/1115-2613.278256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmed RO, Sewram V, Oyesegun AR, et al. A comparison of clinicopathologic features of prostate cancer between Nigerian and South African black men. Afr J Urol. 2022;28(1):6. doi: 10.1186/s12301-022-00273-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelefsky MJ, Daly ME, Valicenti RK. Low-risk prostate cancer. In: Halperin EC, Wazer DE, Perez CA, Brady LW, editors. Perez and Brady’s Principles and Practice of Radiation Oncology. 6th. Philadelphia: Lippincott & Williams; 2013. pp. 1280–1310. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Population Commission (NPC/Nigeria) and ICF. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. Abuja/Rockville: NPC/ICF; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erhabor O, Hussaini A, Abdulwahab-Ahmed A, et al. Some oxidative stress biomarkers among patients with prostate cancer in Sokoto, North Western Nigeria. Open J Blood Dis. 2022;12:60–78. doi: 10.4236/ojbd.2022.123007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seibel HD. Changing patterns of marriage and the family in Nigeria, 1963–1982. 1988.

- 42.Hayes RB, Pottern LM, Strickler H, et al. Sexual behavior, STDs, and risks for prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82(3):718–725. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oyediran K, Isiugo-Abanihe UC, Feyisetan BJ, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with extramarital sex among Nigerian men. Am J Mens Health. 2010;4(2):124–134. doi: 10.1177/1557988308330772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cirakoglu A, Benli E, Yuce A. Polygamy and sexual behavior in a population under risk for prostate cancer diagnosis: an observational study from the Black Sea Region in Turkey. Int Braz J Urol. 2018;44(4):704–708. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2017.0525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albaugh JA, Sufrin N, Lapin BR, et al. Life after prostate cancer treatment: a mixed-methods study of the experiences of men with sexual dysfunction and their partners. BMC Urol. 2017;17(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s12894-017-0231-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soni JS, Oparah AC, Osejie F, et al. Quality of life of patients treated for prostate cancer in a Nigerian hospital. J Sci Pract Pharm. 2017;4(1):169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rousseau L, Dupont A, Labrie F, et al. Sexuality changes in prostate cancer patients receiving antihormonal therapy combining the antiandrogen flutamide with medical (LHRH agonist) or surgical castration. Arch Sex Behav. 1988;17(1):87–98. doi: 10.1007/BF01542054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White ID, Wilson J, Aslet P, et al. Development of UK guidance on the management of erectile dysfunction resulting from radical radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(1):106–123. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiann BP. Effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of erectile dysfunction. Urol Sci. 2010;21(4):163–168. doi: 10.1016/S1879-5226(10)60037-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee TK, Handy AB, Kwan W, et al. Impact of prostate cancer treatment on the sexual quality of life for men who have sex with men. J Sex Med. 2015;12(12):2378–2386. doi: 10.1111/jsm.13030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia Understanding Sexual Issues Following Prostate Cancer Treatment: Information for Men and Their Partners on Possible Sexual Side Effects of Prostate Cancer Treatment and How to Manage Them. [ https://www.pcfa.org.au/media/790757/pcf13464_-_07_-_understanding_sexual_issues_booklet_6.pdf]

- 52.Vázquez-Salas RA, Torres-Sánchez L, López-Carrillo L, et al. History of gonorrhea and prostate cancer in a population-based case-control study in Mexico. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;40:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strickler HD, Goedert JJ. Sexual behavior and evidence for an infectious cause of prostate cancer. Epidemiol Rev. 2001;23(1):144–151. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a000781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramsey SD, Zeliadt SB, Blough DK, et al. Impact of prostate cancer on sexual relationships: a longitudinal perspective on intimate partners' experiences. J Sex Med. 2013;10(12):3135–3143. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.