Keywords: basolateral inwardly rectifying K+ channels, Dahl salt-sensitive rats, high-K+ diet, Kcnj13, ML418

Abstract

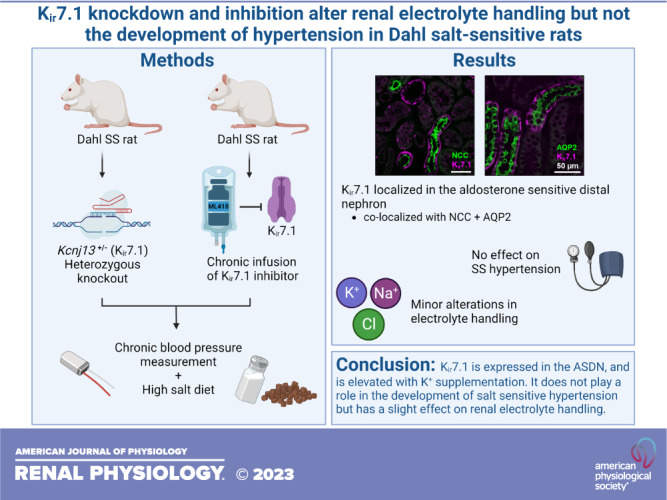

High K+ supplementation is correlated with a lower risk of the composite of death, major cardiovascular events, and ameliorated blood pressure, but the exact mechanisms have not been established. Inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channels expressed in the basolateral membrane of the distal nephron play an essential role in maintaining electrolyte homeostasis. Mutations in this channel family have been shown to result in strong disturbances in electrolyte homeostasis, among other symptoms. Kir7.1 is a member of the ATP-regulated subfamily of Kir channels. However, its role in renal ion transport and its effect on blood pressure have yet to be established. Our results indicate the localization of Kir7.1 to the basolateral membrane of aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron cells. To examine the physiological implications of Kir7.1, we generated a knockout of Kir7.1 (Kcnj13) in Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats and deployed chronic infusion of a specific Kir7.1 inhibitor, ML418, in the wild-type Dahl SS strain. Knockout of Kcnj13 (Kcnj13−/−) resulted in embryonic lethality. Heterozygous Kcnj13+/− rats revealed an increase in K+ excretion on a normal-salt diet but did not exhibit a difference in blood pressure development or plasma electrolytes after 3 wk of a high-salt diet. Wild-type Dahl SS rats exhibited increased renal Kir7.1 expression when dietary K+ was increased. K+ supplementation also demonstrated that Kcnj13+/− rats excreted more K+ on normal salt. The development of hypertension was not different when rats were challenged with high salt for 3 wk, although Kcnj13+/− rats excrete less Na+. Interestingly, chronic infusion of ML418 significantly increased Na+ and Cl− excretion after 14 days of high salt but did not alter salt-induced hypertension development. Here, we found that reduction of Kir7.1 function, either through genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition, can influence renal electrolyte excretion but not to a sufficient degree to impact the development of SS hypertension.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY To investigate the role of the Kir7.1 channel in salt-sensitive hypertension, its function was examined using complementary genetic and pharmacological approaches. The results revealed that although reducing Kir7.1 expression had some impact on maintaining K+ and Na+ balance, it did not lead to a significant change in the development or magnitude of salt-induced hypertension. Hence, it is probable that Kir7.1 works in conjunction with other basolateral K+ channels to fine-tune membrane potential.

INTRODUCTION

The link between Na+ consumption and hypertension has been established for decades (1). This mechanism, known as salt sensitivity, is thought to have occurred in our distant ancestors as a way to conserve Na+, which was scarce compared with the modern Western diet (2). Salt sensitivity combined with today’s high amounts of Na+ consumption is a large contributor to the rising rates of hypertension seen in modern society. Contrary to Na+, K+ is associated with ameliorating blood pressure, with K+ supplementation reducing the severity of salt-induced hypertension in rats, which can be determined by the Na+-to-K+ ratio (3–5). Clinical and population studies have found that high urinary K+ is indicative of a healthier diet and is inversely correlated with blood pressure and cardiovascular mortalities (6–9).

The kidneys play a vital role in K+ homeostasis, where nearly 90% of K+ is absorbed by the proximal tubule (PT) and loop of Henle, with fine tuning occurring in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron (ASDN) (10–12). Multiple inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channels are expressed in the kidney (13). Kir channels are a diverse family of channels expressed in a wide variety of tissues and, under certain conditions, display an inward rather than outward movement of K+ (14). This “anomalous” characteristic is largely due to the structure of the channels, which contain a single pore that can become blocked by Mg2+ or polyamines, preventing the outward flow of K+ (14, 15). Kir1.1 [or the renal outer medullary K+ channel (ROMK)] is expressed in the apical membrane, whereas others are localized in the basolateral membranes of polarized renal epithelial cells (13). Kir channels have been shown to be critical for K+ homeostasis. Specifically, changes in apical Kir1.1 and basolateral Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channel function have been linked to salt wasting disorders, specifically Bartter’s syndrome, and EAST/SeSAME syndrome, respectively (16–21). In addition, basolateral Kir4.1/Kir5.1 has been shown to be vital for proper salt handling and maintaining normal blood pressure (22, 23). Kir4.1 and Kir5.1 are found in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), connecting tubule (CNT), and collecting duct (CD), where they form homomeric (only Kir4.1) or heteromeric (Kir4.1/Kir5.1) channels. In many tissues, basolateral Kir channels are functionally coupled with Na+-K+-ATPase and help to maintain resting membrane potentials by acting as “K+ recyclers,” thereby driving the reabsorption of Na+ and secretion of K+ (13, 14, 17, 24). Previous work in our laboratory has revealed that genetic ablation of the gene encoding Kir5.1, Kcnj16, on the Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rat background produced a phenotype of salt wasting, severe hypokalemia, hypotension, and mortality when stressed with a high-salt diet; however, when the high-salt diet was combined with K+ supplementation, Kcnj16 knockout rats did not develop SS hypertension (23). Furthermore, high K+ prevented mortality induced by repeated sound-induced seizures shown in this model (25). In addition to these critical channels, another and less-studied Kir channel, Kir7.1, is found in the kidney, where its role in renal K+ handling and blood pressure regulation is largely unknown.

Kir7.1, encoded by Kcnj13, was identified over 20 years ago and has been found to be expressed in the retina, thyroid, and kidney, among other tissues (26–29). Kir7.1 is essential for proper development; it was found that global knockout in mice results in postnatal lethality due to improper development of the lungs and cleft palate (30). In the thyroid and choroid plexus, it colocalizes with Na+-K+-ATPase, where it is believed to function akin to the other Kir channels to recycle K+ and maintain resting membrane potential (28). A role of Kir7.1 in energy homeostasis control has also been proposed (31). In humans, mutations in Kir7.1 have been linked with retinal disease, but no correlations have suggested electrolyte imbalances in human patients (32, 33). A few studies that have examined the role of Kir7.1 in the kidney have indicated that Kir7.1 may be expressed in the PT, thick ascending limb (TAL), DCT, and CD (27, 34, 35). Notably, it has been predicted that renal Kir7.1 expression depends on dietary K+ supplementation (27). Overall, limited information is available about the role of Kir7.1 in the kidney and the possible implications it might have on renal function. Thus, the main goal of the present study was to uncover the potential role of Kir7.1 in the kidney and its contribution to the progression of SS hypertension. We hypothesized that reduced expression of Kir7.1 would attenuate SS blood pressure development. Here, we found that Kir7.1 is expressed in the DCT, CNT, and CD nephron segments and that its expression is augmented with K+ supplementation. We also described that genetic or pharmacological inhibition of Kir7.1 has a minimal effect on electrolyte excretion, which was insufficient to ameliorate the development of SS hypertension.

METHODS

Animals

All experiments involving animals followed the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all protocols were reviewed and approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin or University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Using CRISPR/Cas9, a mutation was introduced in the Kcnj13 gene of SS/JrHsdMcwi rat embryos. One base pair was inserted in exon 2, resulting in a frameshift mutation. Homozygous knockout resulted in embryonic lethality; thus, heterozygous animals (Kcnj13+/−) were used. Wild-type (WT) male littermates (Kcnj13WT) and Kcnj13+/− animals were weaned at 3 wk of age and maintained on a normal-salt (0.4% NaCl, 0.36% K+) diet (D113755, Dyets).

At 8 wk of age, animals were implanted with radio telemeters (PA-C40, Data Sciences) as previously described (23). Once blood pressures stabilized after surgery, animals were switched to a high-salt (4% NaCl, 0.36% K+) diet (D113756, Dyets) for 3 wk. For experiments with K+ supplementation, animals were switched to a normal-salt (0.4% NaCl), high-K+ (1.41% K+) diet for 1 wk (D113521, Dyets), and then 3 wk on a high-salt (4% NaCl), high-potassium (1.41% K+) diet (D113522, Dyets). High-K+ diets were supplemented with KCl. For drug infusion experiments, the femoral arteries and veins of the animals were catheterized at 8 wk of age to allow simultaneous chronic blood pressure measurements and drug infusion, as previously described (36). After blood pressure stabilized following surgery, animals were chronically infused with the specific Kir7.1 inhibitor ML418 (PC-60576, ProbeChem) or vehicle solution (37). WT SS rats were treated with the inhibitor to mimic and recapitulate the reduction of Kir7.1 expression in heterozygous animals. ML418 was dissolved in a heparinized mixture of 2% DMSO and 98% saline (0.9% NaCl) and was administered at 2.4 mg/kg body wt/day. Drug or vehicle solutions were administered at a rate of 12 mL/day intravenously, and heparinized saline was infused at 2.5 mL/day intra-arterially. After 1 day of infusion, diets were switched to an 8% NaCl diet (D100078, Dyets), and plasma and urine were collected both before infusion and on day 14 of the 8% NaCl diet. This protocol was performed over 2 wk rather than 3 wk due to drug availability as well as the invasiveness of the surgery. After the dietary protocols were finished, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane, and the kidneys were flushed with PBS before euthanasia. The kidneys were collected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and fixed in 10% formalin.

Plasma and Urine Measurements

Prior to the diets being switched and on the final day of the high-salt diet, animals were placed in metabolic cages overnight for 24-h urine collection. Upon completion of the dietary protocols, animals were anesthetized, and blood was collected by canulation of the abdominal descending aorta and spun at 6,000 RCF for 5 min to separate and collect plasma. A radiometer (ABL800 FLEX, Radiometer America) was used to measure electrolyte (K+, Na+, Cl−, and Ca2+) concentration in urine. Urinary electrolyte values were normalized to creatinine.

Immunohistochemistry

The kidneys of anesthetized animals were flushed with PBS, collected, fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Tissues were then sliced into 4-µm sections and deparaffinized for histology and immunolabeling as previously described (23). To examine renal damage, tissue sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome. Whole kidney slides were scanned, and ImageJ software was used to threshold the percent area of cortical fibrosis and medullary protein casts. Immunolabelling for Kir7.1 (sc-398810, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was performed as previously described at a concentration of 1:50 (23). For double immunofluorescence, kidney tissue was labeled with mouse Kir7.1 (sc-398810) and rabbit Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC; AB3553, EMD Millipore) or aquaporin-2 (AQP2; sc-28629, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or 647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to visualize the colocalization of proteins. Images were taken with an Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope with a ×40 objective and oil immersion.

Western Blot Analysis and mRNA Analysis

Lysates for Western blot analysis were prepared by sonicating the frozen kidney cortex in 4× Laemmli buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Membranes were blocked in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 with 2% BSA for 1 h. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at a concentration of 1:1,000. The primary antibodies used were as follows: NCC (AB3553, EMD Millipore), phosphorylated (p)NCC (p1311-53, Phosphosolutions), α-epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC; spc-403D-HRP, StressMarq), β-ENaC (SPC-404D-HRP, StressMarq), γ-ENaC (SPC-405D-HRP, StressMarq), and Na+-K+-ATPase α1 (sc-21712). β-Actin, β-tubulin, and GAPDH were used as loading controls. Data were analyzed using Image Lab software (Image Lab 6.1, Bio-Rad).

For quantitative PCR, saline-perfused, flash-frozen kidney cortices from rats that had undergone different dietary protocols were used to extract total RNA using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA was quantified using a Synergy Neo2 plate reader (BioTek). From each sample, 1 µg of RNA was taken to produce cDNA using a Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the Applied Biosystems MiniAmp Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific). First, multiple specific primer pairs were designed to identify the rat Kcnj13 gene and tested with different concentrations of the same cDNA sample. The PCR products were sequenced (GeneWiz, Azenta) and cross-referenced to make sure the primers were amplifying Kcnj13 specifically. The best primer pair (Table 1) was chosen based on identity (>99%, BLAST, National Center for Biotechnology Information). Next, using Bullseye EvaGreen qPCR Master Mix (MedSci, Valley Park, MO), quantitative PCR was done for the experimental samples (QuantStudio 6 Pro, applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Kcnj13 mRNA relative quantification was determined by normalizing it to 18s.

Table 1.

Sequences for quantitative PCR primers

| Gene | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Kcnj13 | TCCCACAAAAGAACTGAGAAACAC | GACCTCTTTGAGCACCATCCA |

| 18s | CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA | CCTGTATTGTTATTTTTCGTCACTACCT |

Statistical Analysis

Graph Pad Prism 9.3 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis. Student’s t test was used to compare data, and a Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. In cases where two variables were present, two-way ANOVA was used with Holm-Sidak for multiple comparisons. Data are reported as means ± SE with statistical significance defined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Role of Kcnj13 in the Development of SS Hypertension and Kidney Function

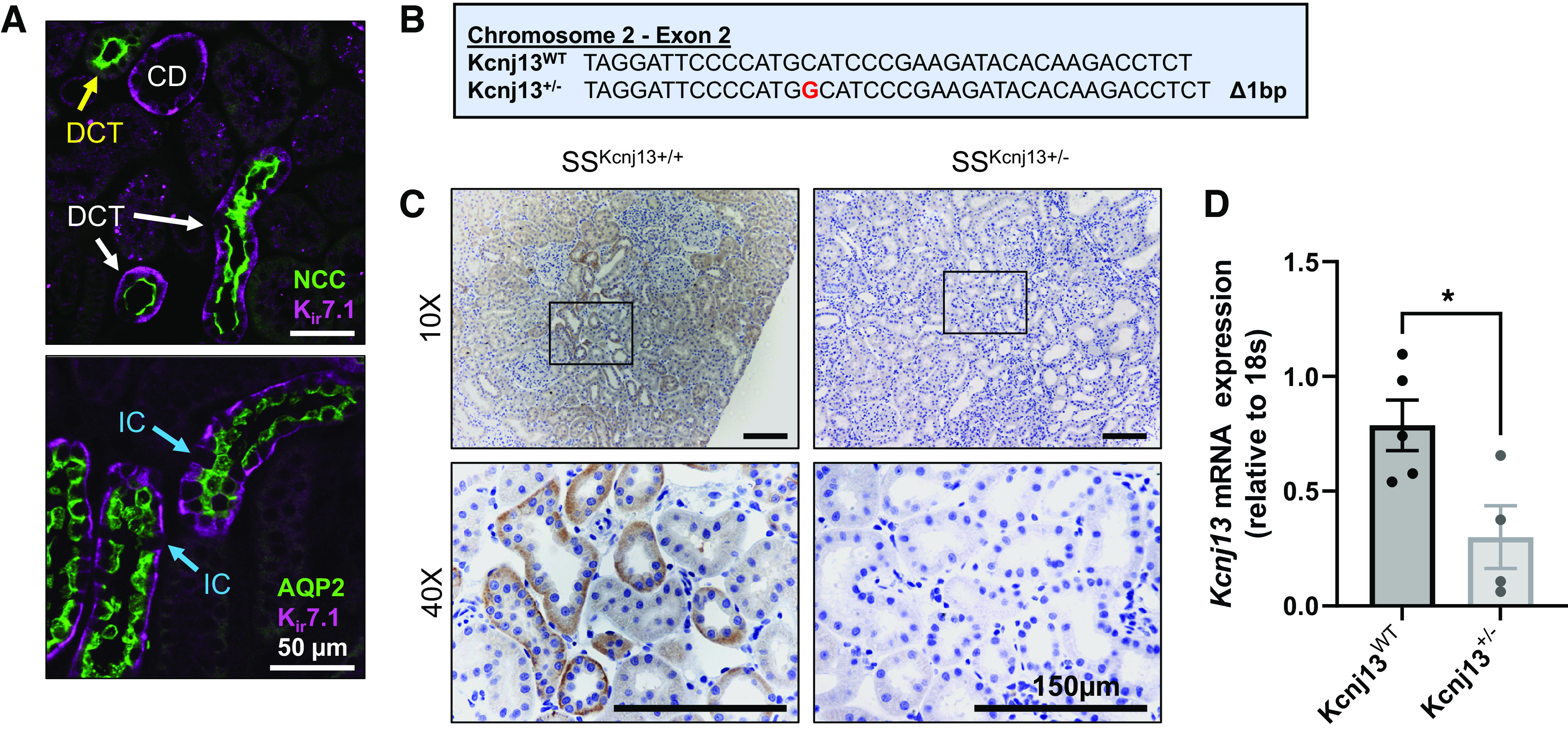

Double immunolabeling of WT rat kidney tissue indicated that Kir7.1 was predominantly expressed in the basolateral membrane of DCT and CD nephron segments of the ASDN. Expression in the DCT, CNT, and CD was confirmed by colocalization of Kir7.1 with NCC and AQP2, respectively (Fig. 1A). Certain DCT nephron segments expressing NCC were not colocalized with Kir7.1, indicating that it was only expressed in one of the two DCT subsegments, most likely DCT2. AQP2 was expressed in the CNT and principal cells of the CD, and, as shown in Fig. 1A, Kir7.1 was not expressed in intercalated cells. To test the effect of Kir7.1 on the regulation of renal electrolyte handling and SS hypertension, we developed a knockout of Kcnj13 on the Dahl SS rat background (Fig. 1B). Homozygous knockout was embryonically lethal. Thus, heterozygous animals (Kcnj13+/−) were used for the following experiments. Figure 1C shows immunohistochemistry staining for Kir7.1 in the kidney tissue of Kcnj13WT and Kcnj13+/− animals, demonstrating a substantial reduction of Kir7.1 expression in heterozygous rats. Quantitative PCR revealed significantly reduced expression of Kcnj13 in heterozygous animals fed a normal-salt diet (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

Kir7.1 is localized in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron. A: immunofluorescent labeling of male salt-sensitive (SS) rat kidney tissue showing colocalization of Kir7.1 with Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC; top) and aquaporin 2 (AQP2; bottom). White arrows indicate distal convoluted tubule (DCT) segments, with the yellow arrow pointing to a DCT only with NCC. Blue arrows indicate intercalated cells (ICs), where there was no expression of AQP2 or Kir7.1. Scale bar = 50 µm. B: genomic DNA sequences for the wild type (WT) and mutant. C: immunohistochemistry labeling of Kir7.1 in the WT and heterozygous kidney cortex. Representative images of n = 2 subjects are shown. Scale bar = 150 µm. D: mRNA expression of Kcnj13 normalized to 18s in the kidney cortex from WT and heterozygous rats fed a 0.4% NaCl diet. Student’s t test was used to compare differences between groups. n ≥ 4 subjects. CD, collecting duct. *P < 0.05.

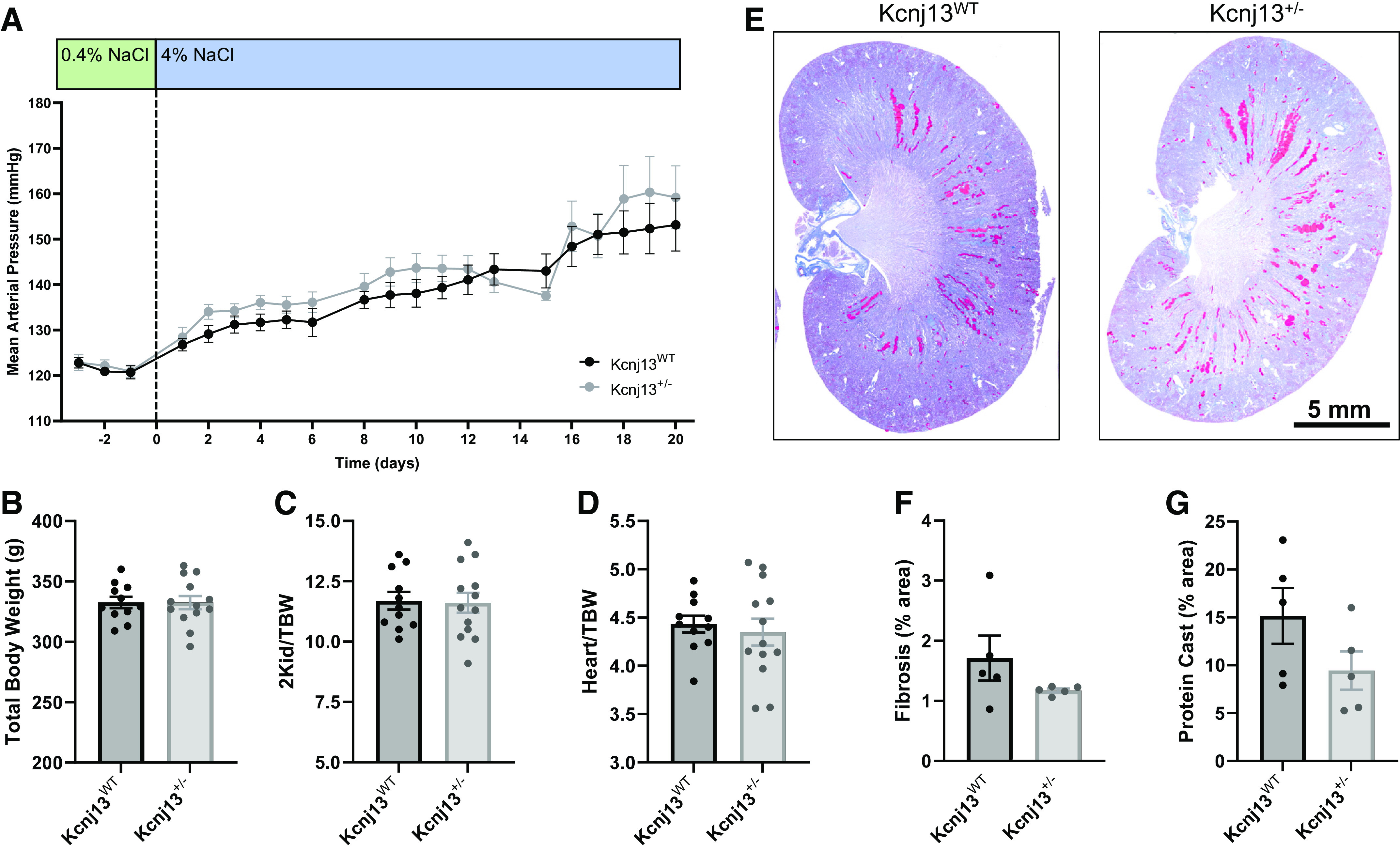

End-point plasma electrolytes from rats on a normal-salt (0.4% NaCl) diet revealed no differences between groups (Table 2). Blood pressure recordings indicated that after 3 wk on a high-salt (4% NaCl) diet, there was no difference in the development of hypertension between WT and knockout rats (Fig. 2A). There were no differences in plasma electrolytes at the end point (Table 3); however, when we examined urinary electrolytes, K+ excretion was significantly increased in Kcnj13+/− rats on a normal-salt (0.4% NaCl) diet. Although Na+ excretion did not significantly change over the course of the dietary protocol, there was a trend in increased excretion in Kcnj13+/− animals at each time point (Table 4). Body weights (Fig. 2B), two kidney-to-body weight ratios (Fig. 2C), and heart-to-body weight ratios (Fig. 2D) were not different between WT and heterozygous rats. Representative kidney images (Fig. 2E) stained with Masson’s trichrome showed no difference in cortical fibrosis (Fig. 2F) or medullary protein casts (Fig. 2G), indicating that there was no impact of knockout on renal tissue damage.

Table 2.

End-point plasma electrolytes after a 0.4% NaCl diet

| Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | |

|---|---|---|

| K+, mmol/L | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 |

| Na+, mmol/L | 141 ± 1 | 142 ± 1 |

| Ca2+, mmol/L | 1.32 ± 0.03 | 1.34 ± 0.02 |

| Cl−, mmol/L | 102 ± 1 | 102 ± 2 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.50 ± 0.06 | 0.48 ± 0.10 |

| pH | 7.33 ± 0.02 | 7.30 ± 0.04 |

Figure 2.

Heterozygous knockout of Kcnj13 does not affect the development of salt-sensitive hypertension. A: daily average mean arterial pressure of male Kcnj13WT and Kcnj13+/− rats on a 0.4% NaCl diet followed by 3 weeks on a 4% NaCl diet. Values are averages of recordings from 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare differences between groups. n ≥ 10 subjects for both groups. Total body weight (B), ratio of kidney weight to total body weight (2Kid/TBW; C), and ratio of heart to total body weight (Heart/TBW; D). Data were compared using Student’s t test. n ≥ 11 subjects. E: representative images of whole kidneys from Kcnj13WT and Kcnj13+/− rats stained with Masson’s trichrome. F: percentage of cortical fibrosis. G: percentage of medullary protein casts. Data were compared with Student’s t test. n = 5 subjects. WT, wild type.

Table 3.

End-point plasma electrolytes after a 4% NaCl diet

|

|

Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− |

|---|---|---|

| K+, mmol/L | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.1 |

| Na+, mmol/L | 142 ± 1 | 142 ± 0.4 |

| Ca2+, mmol/L | 1.32 ± 0.02 | 1.31 ± 0.01 |

| Cl−, mmol/L | 101 ± 1 | 103 ± 1 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.41 ± 0.1 | 0.32 ± 0.1 |

| pH | 7.37 ± 0.02 | 7.32 ± 0.01 |

Table 4.

Urine electrolytes during the 4% NaCl protocol

|

Day 0 (0.4% NaCl) |

Day 7 (4% NaCl) |

Day 14 (4% NaCl) |

Day 21 (4% NaCl) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | |

| K+/creatinine | 11.5 ± 1.1 | 41.9 ± 18.3* | 20.3 ± 3.3 | 31.1 ± 9.6 | 21.4 ± 5.1 | 29.3 ± 10.9 | 14.0 ± 0.6 | 15.6 ± 1.9 |

| Na+/creatinine | 7 ± 1 | 33 ± 14 | 126 ± 16 | 242 ± 57 | 110 ± 16 | 189 ± 44 | 91 ± 11 | 117 ± 16 |

| Ca2+/creatinine | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.12 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | 1.13 ± 0.29 | 0.58 ± 0.08 | 0.78 ± 0.15 | 0.47 ± 0.08 | 0.62 ± 0.11 |

| Cl−/creatinine | 14 ± 2 | 65 ± 30 | 149 ± 29 | 237 ± 55 | 126 ± 17 | 197 ± 48 | 89 ± 11 | 119 ± 16 |

| Creatinine, mM | 18.20 ± 2.58 | 12.35 ± 2.4 | 4.17 ± 0.74 | 2.48 ± 0.58 | 3.49 ± 0.47 | 3.38 ± 0.61 | 4.78 ± 0.66 | 3.69 ± 0.61 |

*Statistical significance.

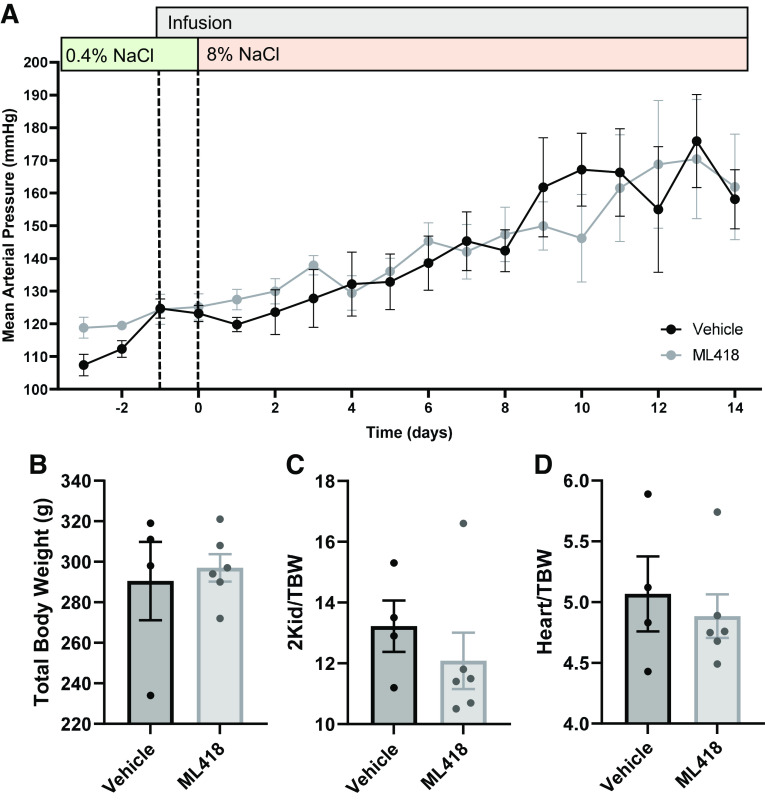

Effect of Inhibition of Kcnj13 on the Development of SS Hypertension

To complement and confirm our observations with genetic modulation of Kir7.1, we used available pharmacological tools. WT SS rats were infused with ML418, a specific Kir7.1 inhibitor, or with vehicle solution (37). Following 1 day of infusion, rats were switched to a high-salt (8% NaCl) diet for 2 wk. There were no differences in the development of blood pressure between the treated and vehicle groups (Fig. 3A). In addition, no differences were observed in total body weights (Fig. 3B), two kidney-to-body weight ratios (Fig. 3C), or heart-to-body weight ratios (Fig. 3D). End-point plasma electrolytes were not different between treated or vehicle groups (Table 5), but Na+, Ca2+, and Cl− excretion were significantly increased in animals treated with ML418 after 14 days of 8% NaCl (Table 6).

Figure 3.

Pharmacological inhibition of Kir7.1 does not affect the development of salt-sensitive hypertension. A: daily average mean arterial pressure of male wild-type salt-sensitive rats with chronic infusion of the Kir7.1 inhibitor ML418 or vehicle alongside an 8% NaCl diet. Values are averages of recordings from 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare differences between groups. n ≥ 4 subjects for both groups. Total body weight (B), ratio of kidney weight to total body weight (2Kid/TBW; C), and ratio of heart to total body weight (Heart/TBW; D). Data were compared using Student’s t test. n ≥ 4 subjects.

Table 5.

End-point plasma electrolytes after 8% NaCl and ML418 infusion

| Vehicle | ML418 | |

|---|---|---|

| K+, mmol/L | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.1 ± 0.1 |

| Na+, mmol/L | 142 ± 1 | 143 ± 1 |

| Ca2+, mmol/L | 1.37 ± 0.02 | 1.34 ± 0.02 |

| Cl−, mmol/L | 102 ± 0 | 103 ± 1 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.62 ± 0.15 | 0.54 ± 0.09 |

| pH | 7.13 ± 0.03 | 7.18 ± 0.02 |

Table 6.

Urine electrolytes during the ML418 infusion protocol

| 0.4% NaCl |

Infusion + 14 Days of 8% NaCl |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | ML418 | Vehicle | ML418 | |

| K+/creatinine | 14.7 ± 0.7 | 13.7 ± 0.9 | 15.8 ± 0.3 | 18.3 ± 0.7 |

| Na+/creatinine | 33 ± 2 | 35 ± 4 | 197 ± 54 | 333 ± 21* |

| Ca2+/creatinine | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.56 ± 0.12 | 1.41 ± 0.28 | 2.60 ± 0.21* |

| Cl−/creatinine | 40 ± 2 | 41 ± 4 | 190 ± 50 | 314 ± 17* |

| Creatinine, mM | 9.38 ± 0.72 | 8.42 ± 0.65 | 2.05 ± 0.91 | 0.95 ± 0.08 |

*Statistical significance.

Effect of K+ Supplementation on the Development of SS Hypertension in Kcnj13 Knockout Rats

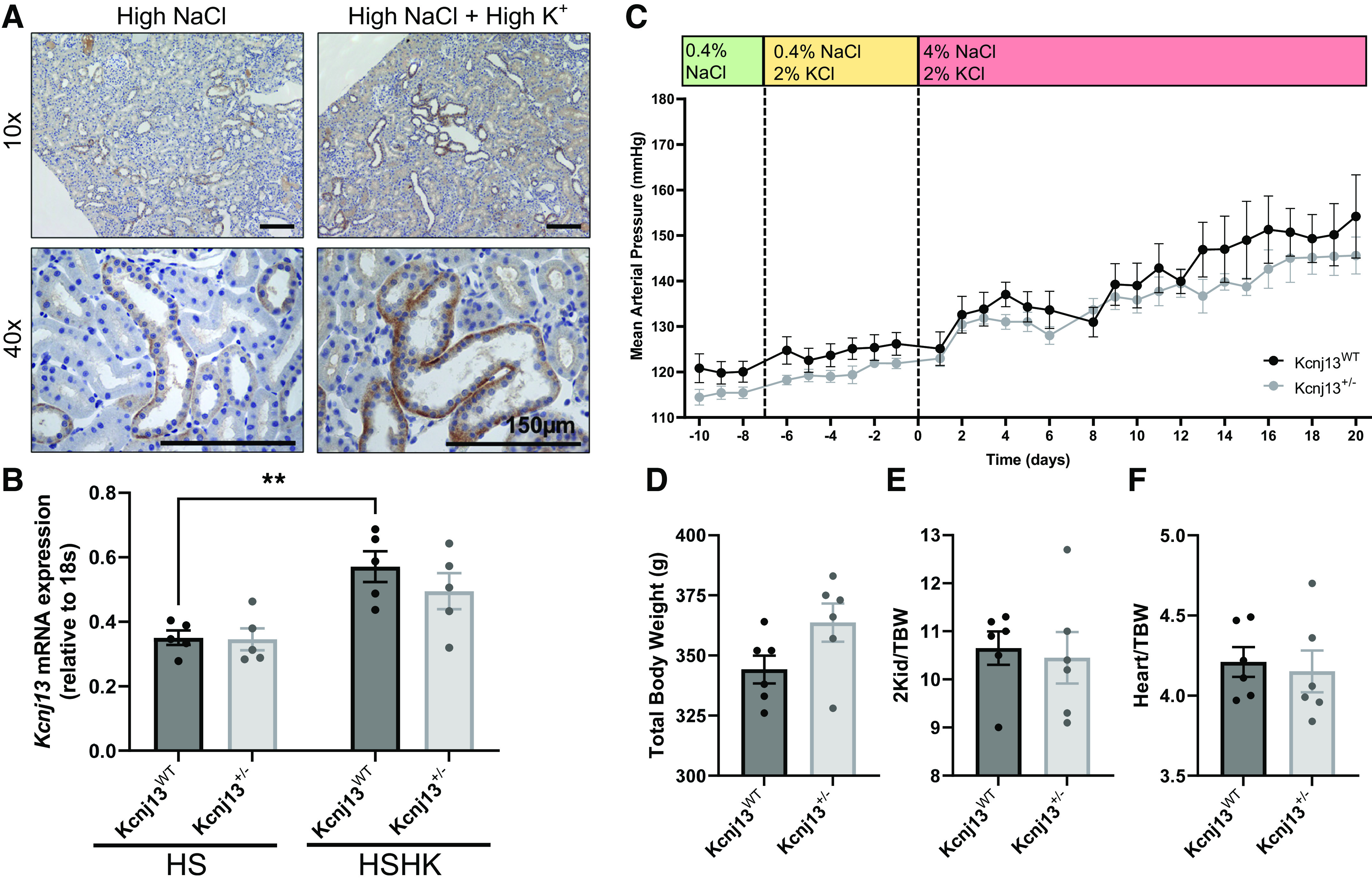

It has been previously observed that high dietary K+ amplifies the expression of Kir7.1 in Sprague-Dawley rats (27). Therefore, we evaluated if supplementation with high K+ (1.41% K+) influences Kir7.1 expression in Dahl SS rats and whether a high-K+ diet affects the progression and magnitude of salt-induced hypertension in Kcnj13+/− rats. WT SS rats on a high-salt diet supplemented with high K+ exhibited increased immunohistological staining for Kir7.1 (Fig. 4A). Quantitative PCR analysis confirmed the increase in Kcnj13 with K+ supplementation (Fig. 4B) in WT rats, with a trend toward an increase in heterozygous animals. After 3 wk on a 4% NaCl diet with 1.41% K+, there was no difference in blood pressure development between Kcnj13WT and Kcnj13+/− rats (Fig. 4C), no differences in body weights (Fig. 4D), two kidney-to-body weight ratios (Fig. 4E), or heart-to-body weight ratios (Fig. 4F). End-point plasma electrolyte values were not different (Table 7) between groups. Interestingly, Kcnj13+/− rats displayed increased K+ excretion after 1 wk of 1.41% K+ on normal salt and decreased Na+ excretion after 3 wk of high salt and 1.41% K+ (Table 8).

Figure 4.

K+ supplementation does not affect salt-sensitive blood pressure development in Kcnj13+/− rats. A: representative images of immunohistochemistry staining for Kir7.1 in male wild-type (WT) salt-sensitive kidney tissue on a high-salt diet and a K+-supplemented high-salt diet. Representative images of n = 2 subjects are shown. Scale bar = 150 µm. B: mRNA expression of Kcnj13 normalized to 18s in high salt (HS) and HS supplemented with high K+ (HSHK) in the WT and heterozygous kidney cortex. Two-way ANOVA was used to compare differences between groups. n = 5 subjects for each group. C: daily average mean arterial pressure of Kcnj13WT and Kcnj13+/− rats on a 0.4% NaCl diet followed by 1 wk of 1.41% K+ supplementation and 3 wk on a 4% NaCl, 1.41% K+-supplemented diet. Values are averages of recordings from 9:00 AM to 12:00 PM. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare differences between groups. n ≥ 5 subjects for both groups. **P < 0.005. D–F: total body weight (D), ratio of kidney weight to total body weight (2Kid/TBW; E), and ratio of heart to total body weight (Heart/TBW; F). Data were compared using Student’s t test. n ≥ 5 subjects.

Table 7.

End-point plasma electrolytes after 4% NaCl and 1.41% K+ diets

| Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | |

|---|---|---|

| K+, mmol/L | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 |

| Na+, mmol/L | 139 ± 1 | 139 ± 1 |

| Ca2+, mmol/L | 1.33 ± 0.02 | 1.34 ± 0.02 |

| Cl−, mmol/L | 103 ± 1 | 102 ± 1 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.56 ± 0.17 | 0.29 ± 0.20 |

| pH | 7.21 ± 0.03 | 7.20 ± 0.02 |

Table 8.

Urine electrolytes during the K+ supplementation protocol

|

Day 0 (0.4% NaCl + 1.41% K+) |

Day 7 (4% NaCl + 1.41% K+) |

Day 21 (4% NaCl + 1.41% K+) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | Kcnj13WT | Kcnj13 +/− | |

| K+/creatinine | 62.4 ± 3.0 | 73.6 ± 3.8* | 60.6 ± 2.7 | 62.0 ± 1.6 | 60.9 ± 3.3 | 54.8 ± 1.1 |

| Na+/creatinine | 13 ± 1 | 16 ± 3 | 132 ± 5 | 135 ± 5 | 130 ± 8 | 103 ± 3* |

| Ca2+/creatinine | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.07 | 1.12 ± 0.11 | 1.04 ± 0.09 | 1.14 ± 0.13 | 0.84 ± 0.06 |

| Cl−/creatinine | 55 ± 3 | 55 ± 5 | 168 ± 6 | 170 ± 7 | 153 ± 15 | 130 ± 3 |

| Creatinine, mM | 6.31 ± 0.50 | 5.14 ± 0.79 | 2.14 ± 0.12 | 1.91 ± 0.11 | 1.94 ± 0.13 | 2.39 ± 0.16 |

*Statistical significance.

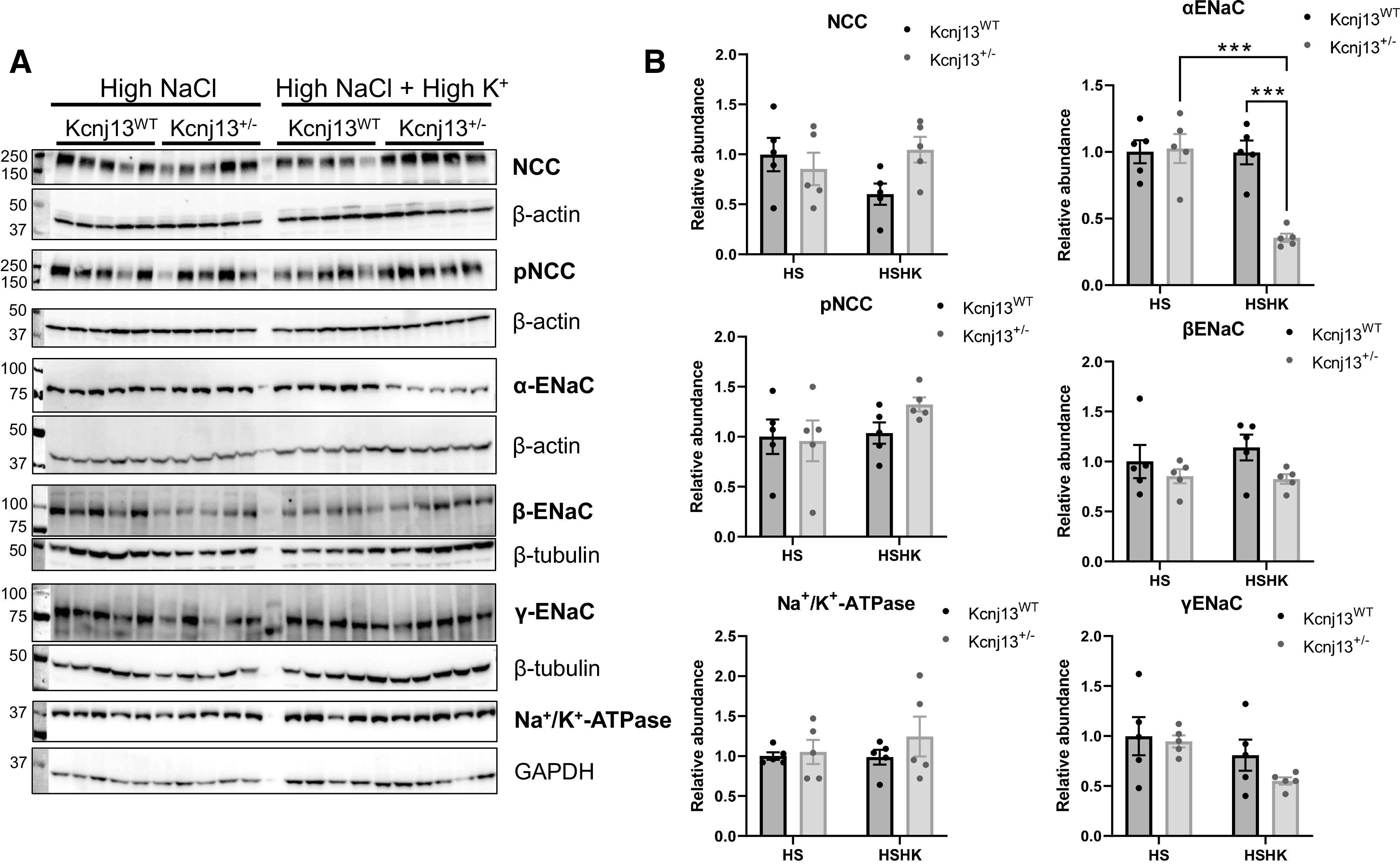

To determine whether mechanisms affecting Na+ homeostasis were altered in Kcnj13+/− rats, we examined the expression of Na+ channels and transporters. Our previous study examining the knockout of Kcnj16, encoding Kir5.1, showed that loss of the channel had a major impact on the expression of channels and transporters in the distal nephron (23). Western blot analysis for NCC, pNCC, α-ENaC, β-ENaC, γ-ENaC, and the Na+-K+-ATPase α1-subunit (Fig. 5) revealed no differences in expression except for α-ENaC, which was significantly decreased in Kcnj13+/− rats on the K+-supplemented high-salt diet. There was a trend toward higher NCC expression in Kcnj13+/− rats under a high-Na+/K+ diet, but this did not reach statistical difference.

Figure 5.

Changes in expression of Na+ channels and transporters in Kcnj13+/− rats fed a high-salt diet. A: Western blot analysis of Na+-Cl− cotransporter (NCC), phosphorylated NCC (pNCC), α-epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC), β-ENaC, γ-ENaC, and Na+/K+-ATPase α1-subunit. B: relative band density normalized to the loading control. Data were compared using two-way ANOVA. n = 5 subjects in each group. ***P < 0.001. HS, high salt; HSHK, HS supplemented with high K+; WT, wild type.

DISCUSSION

Kir channels can have drastic effects on electrolyte homeostasis, and the full extent of these channels should be studied. Kir7.1 has been known to be expressed in the kidney, but its exact function is still unknown. The importance of these channels and the scarce amount of information about Kir7.1 in the kidney led us to question whether it is involved in renal electrolyte handling during SS blood pressure development. Previous literature has demonstrated that Kir7.1 is expressed in various nephron segments; here, we determined its localization to be in the DCT, CNT, and principal cells of the CD, which supported our initial hypothesis that Kir7.1 may be influential in K+ handling in the ASDN. Despite the localization of Kir7.1 implying physiological significance, no clinical evidence has linked mutation in the channel with K+ homeostasis. Initially, on a normal-salt diet, we observed a significant increase in K+ excretion in Kcnj13+/− rats, suggesting that Kir7.1 does play an important part in K+ regulation. Upon the induction of hypertension with the high-salt diet, the difference in K+ excretion was lost, and we did not see any differences in electrolyte homeostasis or in the development of blood pressure between WT and heterozygous rats; however, there was a trend for increased Na+ excretion in the Kcnj13+/− groups. The rats being investigated still likely expressed some levels of Kir7.1 due to the heterozygous knockout. Therefore, we tested the effect of pharmacological blockade using the selective Kir7.1 inhibitor ML418 (37). When we examined urinary electrolytes, ML418-treated rats significantly excreted more Na+, Ca2+, and Cl−, which was consistent with the trend we observed in heterozygous knockout rats. Nevertheless, despite this difference in excretion, there were no differences in plasma electrolytes or blood pressure. Given that in the previous experiments we observed increased K+ excretion in Kcnj13+/− rats on the normal-salt diet, it could be insightful to examine the use of ML418 in these conditions. The inhibition experiment supported our results from the previous experiments using heterozygous animals, which showed that reduction or inhibition of Kir7.1 can slightly alter electrolyte excretion but is not required to maintain electrolyte homeostasis in SS blood pressure development.

A previous study that examined Kir7.1 in the kidney discovered that its expression is augmented with high dietary K+, which we also observed in SS rats (27). Furthermore, as it was recently reported, high dietary K+ has profound effects on various proteins (38). Thus, we repeated the 3-wk high-salt protocol using Kcnj13WT and Kcnj13+/− rats along with supplemented K+ in an attempt to increase the expression of Kir7.1 in WT animals and elucidate the role of Kir7.1 more clearly. Initially, before the switch to high salt, we again observed increased K+ excretion in heterozygous rats. Yet, despite the increase in Kir7.1 expression, no significant difference was observed in blood pressure development between WT and knockout rats. Previously, we showed that with the loss of Kir5.1 expression, Kir4.1 cytosolic protein expression dramatically increased (albeit it did not go to the plasma membrane), along with changes in other channels and transporters, so potentially other channels or transporters were compensating for the reduction of Kir7.1 (23). We observed a significant decrease in the α-subunit of ENaC in K+-supplemented Kcnj13+/− rats and a significant decrease in Na+ excretion. However, no other changes in Na+ transporters were detected.

Through three separate protocols, we did not observe an evident role for Kir7.1 in electrolyte homeostasis or SS blood pressure development, although, curiously, we did consistently observe that heterozygous knockout of Kir7.1 resulted in increased K+ excretion on a normal-salt diet, with both “normal” and “high” K+ content. Quantitative PCR analysis showed that Kcnj13 levels were significantly lower in heterozygous animals on the normal-salt diet. Moreover, the difference was lost when animals were given high salt; this likely explains why electrolyte differences between the strains were not detected on the high-salt diet. Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channel activity has been previously shown to be modulated by Na+ intake, and it is possible that the same is true of Kir7.1 (39). Kir7.1 might play a role in other organs and the developed model could contribute to our knowledge about this channel. For instance, Kir7.1 plays an important role in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), where it is responsible for apical K+ conductance and is associated with snowflake vitreoretinal degeneration, in which mutation caused depolarization of resting membrane potential, as well as Leber congenital amaurosis (33, 40–43). The retinal pigment epithelium and choroid plexus, where Kir7.1 has been shown to couple with Na+-K+-ATPase in the apical membrane, both lack Kir4.1 and Kir5.1, suggesting that its role is more pronounced in the absence of these channels (44, 45). In the kidney, Kir7.1 may be overshadowed by Kir4.1 and Kir5.1 as well as other K+ channels expressed in the DCT and CD, especially when dealing with the compensatory changes induced by a high-salt diet (28, 40). Kir7.1 was also found to increase from postnatal day 14 to postnatal day 21 in neonate rat kidneys, indicating that it plays an important role in early kidney function and development and might become redundant once the kidney develops (35).

The main limitation of this study is the use of a heterozygous knockout animal, which was necessitated as homozygous animals were embryonic lethal. Previous studies that have examined knockout of ROMK in Dahl SS rats observed postnatal lethality in homozygotes and used heterozygous animals; even with the use of heterozygous animals, these studies revealed important information about ROMK function in SS hypertension (46). In addition, it has been shown that mutation in KCNJ13 resulting in SVD is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (32). It is possible that in our model there was still partial expression of Kir7.1, which would result in the lack of a distinct phenotype, and little to no effect on channel activity may also be responsible; however, electrophysiological studies would need to be performed to confirm this. Ideally, a kidney-specific mutation would be created, but, unfortunately, this degree of genetic modification is not as robust in rats. For future studies, it would be insightful to inhibit other basolateral Kir channels, such as Kir4.1 and Kir5.1, to more clearly observe Kir7.1 and discern whether it might compensate in their absence. We have recently developed a selective Kir4.1/Kir5.1 channel inhibitor that might be suitable for these studies (47). Furthermore, although we assessed only the expression of certain channels and transporters expressed in the ASDN, it would be beneficial to investigate the activity of the channels as well to provide a complete examination of their function.

Perspectives and Significance

With rates of hypertension increasing globally, it is imperative to better understand the multifaceted factors involved in blood pressure control. This study aimed to examine an understudied member of the inwardly rectifying K+ channel family, Kir7.1, to better understand the mechanisms behind electrolyte homeostasis and SS hypertension. We eliminated the function of Kir7.1 using complementary genetic and pharmacological approaches to examine what kind of physiological changes would occur during SS hypertension. We conclude that reduction of Kir7.1 can have a slight effect on K+ and Na+ homeostasis. However, it is insufficient to affect blood pressure significantly and likely serves to fine tune membrane potential under normonatremic conditions alongside other renal K+ channels.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R35HL135749 (to A.S.), R01DK120821 (to J.S.D. and A.S.), K99HL153686 (to C.A.K.), R01DK126720 (to O.P.), and R01DK129227 (to A.S. and O.P.) and by Department of Veteran Affairs Grant I01 BX004024 (to A.S. and O.P.).

DISCLOSURES

C. A. Klemens and A. Staruschenko are editors of the American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology and were not involved and did not have access to information regarding the peer-review process or final disposition of this article. An alternate editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this article. None of the other authors has any conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.Z., O.P., and A.S. conceived and designed research; A.Z., O.P., V.L., L.V.D., C.A.K., and A.G. performed experiments; A.Z., O.P., V.L., L.V.D., C.A.K., and A.G. analyzed data; A.Z., O.P., J.S.D., and A.S. interpreted results of experiments; A.Z. and O.P. prepared figures; A.Z., O.P., and A.S. drafted manuscript; A.Z., O.P., C.A.K., J.S.D., and A.S. edited and revised manuscript; A.Z., O.P., V.L., L.V.D., C.A.K., A.G., J.S.D., and A.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christine Duris (Children’s Research Institute Histology Core) for the help with histology and immunohistochemistry analysis. BioRender was used to prepare the graphical abstract.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kotchen TA, Cowley AW Jr, Frohlich ED. Salt in health and disease – a delicate balance. N Engl J Med 368: 1229–1237, 2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1212606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Weder AB. Evolution and hypertension. Hypertension 49: 260–265, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000255165.84684.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tobian L. Salt and hypertension. Lessons from animal models that relate to human hypertension. Hypertension 17: I52–58, 1991. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.17.1_suppl.i52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dahl LK, Leitl G, Heine M. Influence of dietary potassium and sodium/potassium molar ratios on the development of salt hypertension. J Exp Med 136: 318–330, 1972. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.2.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Staruschenko A. Beneficial effects of high potassium: contribution of renal basolateral K+ channels. Hypertension 71: 1015–1022, 2018. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.10267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mente A, Irvine EJ, Honey RJ, Logan AG. Urinary potassium is a clinically useful test to detect a poor quality diet. J Nutr 139: 743–749, 2009. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.098319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mente A, O'Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Poirier P, Wielgosz A, Morrison H, Li W, Wang X, Di C, Mony P, Devanath A, Rosengren A, Oguz A, Zatonska K, Yusufali AH, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Avezum A, Ismail N, Lanas F, Puoane T, Diaz R, Kelishadi R, Iqbal R, Yusuf R, Chifamba J, Khatib R, Teo K, Yusuf S; PURE Investigators. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med 371: 601–611, 2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Donnell M, Mente A, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Wang X, Liu L, Yan H, Lee SF, Mony P, Devanath A, Rosengren A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lanas F, Yusoff K, Iqbal R, Ilow R, Mohammadifard N, Gulec S, Yusufali AH, Kruger L, Yusuf R, Chifamba J, Kabali C, Dagenais G, Lear SA, Teo K, Yusuf S; PURE Investigators. Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 371: 612–623, 2014. [Erratum in N Engl J Med 371: 1267, 2014]. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Neal B, Wu Y, Feng X, Zhang R, Zhang Y, Shi J, et al. Effect of salt substitution on cardiovascular events and death. N Engl J Med 385: 1067–1077, 2021. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giebisch G. Renal potassium transport: mechanisms and regulation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 274: F817–F833, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.5.F817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Palmer BF. Regulation of potassium homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1050–1060, 2015. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08580813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weinstein AM. A mathematical model of the rat kidney. IV. Whole kidney response to hyperkalemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 322: F225–F244, 2022. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00413.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manis AD, Hodges MR, Staruschenko A, Palygin O. Expression, localization, and functional properties of inwardly rectifying K+ channels in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 318: F332–F337, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00523.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hibino H, Inanobe A, Furutani K, Murakami S, Findlay I, Kurachi Y. Inwardly rectifying potassium channels: their structure, function, and physiological roles. Physiol Rev 90: 291–366, 2010. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nishida M, MacKinnon R. Structural basis of inward rectification: cytoplasmic pore of the G protein-gated inward rectifier GIRK1 at 1.8 A resolution. Cell 111: 957–965, 2002. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Welling PA, Ho K. A comprehensive guide to the ROMK potassium channel: form and function in health and disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F849–F863, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00181.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Palygin O, Pochynyuk O, Staruschenko A. Role and mechanisms of regulation of the basolateral Kir 4.1/Kir 5.1K+ channels in the distal tubules. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 219: 260–273, 2017. doi: 10.1111/apha.12703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scholl UI, Choi M, Liu T, Ramaekers VT, Häusler MG, Grimmer J, Tobe SW, Farhi A, Nelson-Williams C, Lifton RP. Seizures, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, mental retardation, and electrolyte imbalance (SeSAME syndrome) caused by mutations in KCNJ10. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 5842–5847, 2009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bockenhauer D, Feather S, Stanescu HC, Bandulik S, Zdebik AA, Reichold M, Tobin J, Lieberer E, Sterner C, Landoure G, Arora R, Sirimanna T, Thompson D, Cross JH, van't Hoff W, Al Masri O, Tullus K, Yeung S, Anikster Y, Klootwijk E, Hubank M, Dillon MJ, Heitzmann D, Arcos-Burgos M, Knepper MA, Dobbie A, Gahl WA, Warth R, Sheridan E, Kleta R. Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy, and KCNJ10 mutations. N Engl J Med 360: 1960–1970, 2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simon DB, Karet FE, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Hamdan JH, DiPietro A, Trachtman H, Sanjad SA, Lifton RP. Genetic heterogeneity of Barter's syndrome revealed by mutations in the K+ channel, ROMK. Nat Genet 14: 152–156, 1996. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu JZ, Hall AE, Peterson LN, Bienkowski MJ, Eessalu TE, Hebert SC. Localization of the ROMK protein on apical membranes of rat kidney nephron segments. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 273: F739–F748, 1997. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1997.273.5.F739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schlingmann KP, Renigunta A, Hoorn EJ, Forst AL, Renigunta V, Atanasov V, Mahendran S, Barakat TS, Gillion V, Godefroid N, Brooks AS, Lugtenberg D, Lake J, Debaix H, Rudin C, Knebelmann B, Tellier S, Rousset-Rouvière C, Viering D, de Baaij JHF, Weber S, Palygin O, Staruschenko A, Kleta R, Houillier P, Bockenhauer D, Devuyst O, Vargas-Poussou R, Warth R, Zdebik AA, Konrad M. Defects in KCNJ16 cause a novel tubulopathy with hypokalemia, salt wasting, disturbed acid-base homeostasis, and sensorineural deafness. J Am Soc Nephrol 32: 1498–1512, 2021. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020111587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Palygin O, Levchenko V, Ilatovskaya DV, Pavlov TS, Pochynyuk OM, Jacob HJ, Geurts AM, Hodges MR, Staruschenko A. Essential role of Kir5.1 channels in renal salt handling and blood pressure control. JCI Insight 2: e92331, 2017. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.92331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Isaeva E, Bohovyk R, Fedoriuk M, Shalygin A, Klemens CA, Zietara A, Levchenko V, Denton JS, Staruschenko A, Palygin O. Crosstalk between epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) and basolateral potassium channels (Kir 4.1/Kir 5.1) in the cortical collecting duct. Br J Pharmacol 179: 2953–2968, 2022. doi: 10.1111/bph.15779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Manis AD, Palygin O, Isaeva E, Levchenko V, LaViolette PS, Pavlov TS, Hodges MR, Staruschenko A. Kcnj16 knockout produces audiogenic seizures in the Dahl salt-sensitive rat. JCI Insight 6: e143251, 2021. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.143251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krapivinsky G, Medina I, Eng L, Krapivinsky L, Yang Y, Clapham DE. A novel inward rectifier K+ channel with unique pore properties. Neuron 20: 995–1005, 1998. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80480-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ookata K, Tojo A, Suzuki Y, Nakamura N, Kimura K, Wilcox CS, Hirose S. Localization of inward rectifier potassium channel Kir7.1 in the basolateral membrane of distal nephron and collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1987–1994, 2000. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11111987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakamura N, Suzuki Y, Sakuta H, Ookata K, Kawahara K, Hirose S. Inwardly rectifying K+ channel Kir7.1 is highly expressed in thyroid follicular cells, intestinal epithelial cells and choroid plexus epithelial cells: implication for a functional coupling with Na+,K+-ATPase. Biochem J 342: 329–336, 1999. doi: 10.1042/bj3420329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kusaka S, Inanobe A, Fujita A, Makino Y, Tanemoto M, Matsushita K, Tano Y, Kurachi Y. Functional Kir7.1 channels localized at the root of apical processes in rat retinal pigment epithelium. J Physiol 531: 27–36, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0027j.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Villanueva S, Burgos J, López-Cayuqueo KI, Lai KM, Valenzuela DM, Cid LP, Sepúlveda FV. Cleft palate, moderate lung developmental retardation and early postnatal lethality in mice deficient in the Kir7.1 inwardly rectifying K+ channel. PLoS One 10: e0139284, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hernandez CC, Gimenez LE, Dahir NS, Peisley A, Cone RD. The unique structural characteristics of the Kir 7.1 inward rectifier potassium channel: a novel player in energy homeostasis control. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 324: C694–C706, 2023. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00335.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hejtmancik JF, Jiao X, Li A, Sergeev YV, Ding X, Sharma AK, Chan CC, Medina I, Edwards AO. Mutations in KCNJ13 cause autosomal-dominant snowflake vitreoretinal degeneration. Am J Hum Genet 82: 174–180, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pattnaik BR, Shahi PK, Marino MJ, Liu X, York N, Brar S, Chiang J, Pillers DA, Traboulsi EI. A novel KCNJ13 nonsense mutation and loss of Kir7.1 channel function causes leber congenital amaurosis (LCA16). Hum Mutat 36: 720–727, 2015. doi: 10.1002/humu.22807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Derst C, Hirsch JR, Preisig-Müller R, Wischmeyer E, Karschin A, Döring F, Thomzig A, Veh RW, Schlatter E, Kummer W, Daut J. Cellular localization of the potassium channel Kir7.1 in guinea pig and human kidney. Kidney Int 59: 2197–2205, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suzuki Y, Yasuoka Y, Shimohama T, Nishikitani M, Nakamura N, Hirose S, Kawahara K. Expression of the K+ channel Kir7.1 in the developing rat kidney: role in K+ excretion. Kidney Int 63: 969–975, 2003. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Golosova D, Palygin O, Bohovyk R, Klemens CA, Levchenko V, Spires DR, Isaeva E, El-Meanawy A, Staruschenko A. Role of opioid signaling in kidney damage during the development of salt-induced hypertension. Life Sci Alliance 3: e202000853, 2020. doi: 10.26508/lsa.202000853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Swale DR, Kurata H, Kharade SV, Sheehan J, Raphemot R, Voigtritter KR, Figueroa EE, Meiler J, Blobaum AL, Lindsley CW, Hopkins CR, Denton JS. ML418: the first selective, sub-micromolar pore blocker of Kir7.1 potassium channels. ACS Chem Neurosci 7: 1013–1023, 2016. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kortenoeven MLA, Cheng L, Wu Q, Fenton RA. An in vivo protein landscape of the mouse DCT during high dietary K+ or low dietary Na+ intake. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 320: F908–F921, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00064.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wu P, Gao ZX, Su XT, Wang MX, Wang WH, Lin DH. Kir4.1/Kir5.1 activity is essential for dietary sodium intake-induced modulation of Na-Cl cotransporter. J Am Soc Nephrol 30: 216–227, 2019. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2018080799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shimura M, Yuan Y, Chang JT, Zhang S, Campochiaro PA, Zack DJ, Hughes BA. Expression and permeation properties of the K+ channel Kir7.1 in the retinal pigment epithelium. J Physiol 531: 329–346, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0329i.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kumar M, Pattnaik BR. Focus on Kir7.1: physiology and channelopathy. Channels (Austin) 8: 488–495, 2014. doi: 10.4161/19336950.2014.959809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pattnaik BR, Tokarz S, Asuma MP, Schroeder T, Sharma A, Mitchell JC, Edwards AO, Pillers DA. Snowflake vitreoretinal degeneration (SVD) mutation R162W provides new insights into Kir7.1 ion channel structure and function. PLoS One 8: e71744, 2013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sergouniotis PI, Davidson AE, Mackay DS, Li Z, Yang X, Plagnol V, Moore AT, Webster AR. Recessive mutations in KCNJ13, encoding an inwardly rectifying potassium channel subunit, cause leber congenital amaurosis. Am J Hum Genet 89: 183–190, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yang D, Zhang X, Hughes BA. Expression of inwardly rectifying potassium channel subunits in native human retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res 87: 176–183, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Millar ID, Bruce J, Brown PD. Ion channel diversity, channel expression and function in the choroid plexuses. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res 4: 8, 2007. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhou X, Zhang Z, Shin MK, Horwitz SB, Levorse JM, Zhu L, Sharif-Rodriguez W, Streltsov DY, Dajee M, Hernandez M, Pan Y, Urosevic-Price O, Wang L, Forrest G, Szeto D, Zhu Y, Cui Y, Michael B, Balogh LA, Welling PA, Wade JB, Roy S, Sullivan KA. Heterozygous disruption of renal outer medullary potassium channel in rats is associated with reduced blood pressure. Hypertension 62: 288–294, 2013. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.01051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. McClenahan SJ, Kent CN, Kharade SV, Isaeva E, Williams JC, Han C, Terker A, Gresham R 3rd, Lazarenko RM, Days EL, Romaine IM, Bauer JA, Boutaud O, Sulikowski GA, Harris R, Weaver CD, Staruschenko A, Lindsley CW, Denton JS. VU6036720: the first potent and selective in vitro inhibitor of heteromeric Kir4.1/5.1 inward rectifier potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol 101: 357–370, 2022. doi: 10.1124/molpharm.121.000464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.