Abstract

Introduction:

Multiple myeloma is the second most commonly diagnosed hematologic malignancy and has an increasing incidence and prevalence globally, and proteasome inhibitors (PIs) form the backbone of some our most effective regimens for all phases of this disease in fit and frail patients.

Areas Covered:

Strong understanding of the proteasome complex is increasingly important as the rapid development of new PIs and innovative myeloma therapies complicate the use of old and new combination regimens. We focus herein on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the approved PIs and others in development, including their safety and efficacy in corresponding clinical studies.

Expert Opinion:

Advancements such as the first oral PI, ixazomib, with a more convenient route of administration and improved toxicity profile led to an improved quality of life, patient compliance, and all-oral combination regimens which are efficacious for long-term management of standard and high-risk MM. Novel pan-PIs, such as mirazomib, hold the promise of superior clinical activity due to irreversible targeting of all multicatalytic proteinase complex subunits. Development of clinically validated biomarkers of PI sensitivity/resistance is required to inform utilization of the most optimal and effective, rationally targeted PI treatments for all MM patients.

Keywords: myeloma, pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, proteasome inhibitors

1. Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell disorder characterized by an expansion of a clonal population of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Elaboration of disease-related serum and urinary paraproteins can result in end-organ damage manifested as hypercalcemia, renal dysfunction, anemia and widespread destructive skeletal lesions, as well as immune suppression that often precipitates morbidity and mortality. Fortunately, the last nearly two decades of preclinical and clinical development have yielded multiple regulatory approvals by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the management of all phases of the disease. Dramatically improved long-term outcomes in myeloma have been seen since the introduction of immunomodulatory agents (IMiDs)[1] and proteasome inhibitors (PIs) which, together with newly introduced immunotherapies[2], represent the backbones in contemporary management of myeloma patients (patients). Since the early 2000’s, when the first member of the PI class – bortezomib (BTZ) - was introduced and tested[3, 4], two other notable members of the family have joined the anti-myeloma armamentarium: a second-generation PI, carfilzomib (CFZ)[5], and the first oral PI, ixazomib (IXZ)[6]. For this disease that is characterized by inevitable clonal escape and intrinsic and/or acquired drug resistance, optimal combinatorial use of PIs remains essential in the management of what for most patients becomes a long-term, chronic malignancy requiring control. Towards this end, having an adequate understanding of different modes of PI delivery, frequency of dosing, their interaction with other classes of anti-MM agents and their overall safety in an otherwise aging and/or elderly MM patient population is critical. In this review, we will focus on relevant pharmacodynamic (PD), pharmacokinetic (PK), and clinical aspects of all approved PIs for the treatment of myeloma, and will comment on those that are promising in development.

2. Overview of the markets

The first PI to enter the clinic was BTZ, which was FDA-approved in 2003 for relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM)[4, 7], and in 2008 for newly diagnosed MM (NDMM)[8]. These and many later approvals were based on studies that delivered BTZ intravenously, while a later non-inferiority trial established subcutaneous (SC) administration as an alternative and preferred route[9](Table 1). The EMA granted BTZ a marketing authorization in 2004 (Table 2), where it is used in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or dexamethasone in RRMM, and with melphalan and prednisone (MP) in transplant-ineligible, or as BTZ-dexamethasone or BTZ-dexamethasone with thalidomide (VTD) in transplant-eligible NDMM[10]. A second-generation PI, CFZ, received its first FDA approval in 2012 with twice weekly dosing[11], and in late 2018 for once-weekly (Kd70) dosing in RRMM. It received marketing authorization from the EMA in 2015, where it is used as KRd or Kd in RRMM[12](Tables 1 and 2). The last member of the PI family to gain regulatory approval, and the very first oral PI, IXZ, received FDA designation in 2015, with a similar indication for IXZ also secured through the EMA in 2016[13](Table 1). Table 2 summarizes some of the other approved PI treatment combinations for NDMM and RRMM[14, 15, 16].

Table 1.

Summary of pivotal clinical trials of approved and developing proteasome inhibitors with efficacy and safety features

| PI | FDA / EMA | Study Phase | Disease Type | Patient No. | Study Regimen | Safety | Efficacy | Ref | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Hematologic G ≥ 3 AEs (%) | Non-Hematologic G ≥ 3 AEs (%) | ORR (%) | PFS (mo) | OS (mo) | |||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Bortezomib | A / A | II | RRMM | 54 | BTZ IV 1.0 or 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly 2 of 3 weeks x 8 cycles, alone or with Dex | 1.3 mg/m2: TCP 23, NP 23, LP 12 | 1.3 mg/m2: PN 15, weakness 12, PNA 15 | 50 | 11 | NR | [7] |

| II | RRMM | 202 | IV BTZ 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 in a 21-day cycle for up to 8 cycles | TCP 31, NP 14 | Fatigue 12, PN 12 | 35 | 7 | 16 | [4] | ||

| III | NDMM | 682 | VMP (BTZ IV 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29, and 32 cycles 1–4 and on days 1, 8, 22, and 29 cycles 5–9 vs. MP 6-week cycles | TCP 37 vs. 30, NP 40 vs. 38, A 19 vs. 28, leukopenia 23 vs. 20, LP 19 vs. 11 |

PNA 7 vs. 5 PN 13 vs 0 |

57 vs 79 | 17 vs 24 | NR vs 43 | [8,39] | ||

| III | NDMM | 525 | 8 VRd 21-day cycles (BTZ IV 1.3 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, Len 25 mg daily on days 1–14, dex 20 mg daily on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12) vs 6 Rd 28-day cycles (Len 25 mg once a day for days 1–21, dex 40 mg once a day on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) | Blood / bone marrow 47 vs. 46, Hemorrhage or bleeding 3 vs. 0, Infection 14 vs. 14 | Neurological 33 vs. 11, Pain 12 vs. 4 Gastrointestinal 22 vs. 7, Metabolic or laboratory 26 vs. 28 |

82 vs 72 | 43 vs 30 | 75 vs 64 | [38] | ||

| Carfilzomib | A / A | II | RRMM | 266 | CFZ IV 20/27 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 of each 28-day cycle | A 24, TCP 29, LP 20, NP 11 | PNA 9.4, fatigue 7.5, hyponatremia 8.3 | 23.7 | 3.7 | 15.6 | [11] |

| III | RRMM | 792 | KRd (CFZ IV 20/27 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 of each 28-day cycle, cycles 1–12, on days 1, 2, 15, and 16 cycles 13–18, Len 25 mg daily on days 1–21, dex 40 mg daily on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) vs Rd 28-day cycles (Len 25 mg once a day for days 1–21, dex 40 mg once a day on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) | A 17.9 vs 17.2, NP 29.6 vs 26.5, TCP 16.6 vs 12.3 |

Hypokalemia 9.4 vs 4.9, Fatigue 7.7 vs 6.4, Hypertension 4.3 vs 1.8, cardiac failure 3.8 vs 1.8 |

87.1 vs 66.7 | 26.3 vs 17.6 | 48.3 vs 40.4 | [65] | ||

| III | RRMM | 929 | Kd (CFZ IV 20/56 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 and dex 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 22, and 23) of each 28-day cycle vs Vd 21-day cycles (BTZ 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, and dex 40 mg on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12) | A 14 vs 10, TCP 9 vs 9 |

Cardiac failure 4 vs 1, PNA 6 vs 7, Acute renal failure 3 vs 2 | 77 vs 72 | 18.7 vs 9.4 | NR | [107] | ||

| III | RRMM | 478 | CFZ IV on days 1, 8, and 15 of all cycles (20 mg/m2 day 1 cycle 1, 70 mg/m2 thereafter vs CFZ IV 20/27 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 of each 28-day cycle; both groups got dex 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15 (all cycles) and 22 (cycles 1–9 only) | A 17 vs 17, TCP 7.1 vs 6.8, NP 5.9 vs 6.8, | PNA 10.1 vs 6.8, fatigue 4.6 vs 2.1 | 62.9 vs 40.8 | 11.2 vs 7.6 | NR | [68] | ||

| Ixazomib | A / A | III | RRMM | 722 | IRd (ixazomib 4 mg on days 1, 8, and 15; Len 25 mg on days 1–21 and dex 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) vs Rd (Len 25 mg on days 1–21 and dex 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) of each 28-day cycle | NP 23 vs 24, TCP 19 vs 9, A 9 vs 13 |

Diarrhea 6 vs 3, rash 5 vs 2, arrhythmia 5 vs 3 | 78 vs 72 | 20.6 vs 14.7 | NR | [76] |

| Marizomib | Na / Na | I | RRMM | 68 | MRZ A IV (0.025–0.7 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of 28-day cycles) and MRZ B (0.15–0.6 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of 21-day cycles; dex was allowed with MRZ B | NP 0 vs 3, LP 3 vs 0, A 3 vs 3, TCP 3 vs 8 | Fatigue 6 vs 6, PN 0 vs 3 |

6 vs 11 | - | - | [97] |

| I | RRMM | 27 | MRZ IV 0.5 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, 11 + dex 20 mg on the day of and either the day before or day after MRZ infusion, in 21-day cycles | TCP 5, LP 2 | Fatigue 5, delirium 5, hallucinations 5, cognitive disorder 5 | 11 | - | - | [96] | ||

| I | RRMM | 36 | MRZ IV 0.5 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, 11, Pom (3–4 mg) on days 1–21; and low dose dex (5 or 10 mg) on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 15, 16, 22 and 23 of every 28-day cycle | NP 29, A 11, TCP 11, LP 5 | PNA 11; constipation 3, diarrhea 3, PN 3, hypertension 3 | 53 | - | - | [99] | ||

| Oprozomib | Na / Na | I | Ad Solid Tumors | 44 | OPZ delivered in escalating once daily (QD) or split doses (SD) on days 1–5 of 14-day cycles | A 4 vs 21 | Vomiting 8 vs 5, dehydration 12 vs 5, fatigue 0 vs 10, nausea and diarrhea 0 vs 5 | 23 | - | - | [104] |

PI: proteasome inhibitor; A: approved; FDA: food and drug administration; EMA: European medicines agency; No: number; G: grade; AE: adverse event; mo: months; ORR: overall response rate; PFS: progression free survival; OS: overall survival; Ref: reference; RRMM: relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma; BTZ: bortezomib; IV: intravenous; dex: dexamethasone; TCP – Thrombocytopenia; NP: neutropenia; LP: lymphopenia; PN: peripheral neuropathy; PNA: pneumonia; NR: not reached; A: anemia, NDMM: newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; vs: versus; VMP: bortezomib, melphalan, prednisone; MP: melphalan, prednisone; A: anemia; VRd: bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; Rd: lenalidomide, dexamethasone; Len: lenalidodmie; CFZ: carfilzomib; KRd: carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; Kd: carfilzomib, dexamethasone; Vd: bortezomib, dexamethasone; IRd: ixazomib lenalidomide, dexamethasone; Na: not approved; MRZ: marizomib; Pom: pomalidomide; Ad: advanced; OPZ: oprozomib.

Table 2.

Summary of commonly used Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency approved proteasome inhibitor treatment combinations for newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma

| PI | FDA | EMA | Disease Type | Drug / Combination Regimen and Administration Schedule | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Bortezomib | Yes | RRMM |

Monotherapy in a 21-day treatment cycle: Bortezomib IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 Combination therapy with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in a 21-day treatment cycle: Bortezomib IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin IV 30 mg/m2 on day 4 Combination with dexamethasone in a 21-day treatment cycle: Bortezomib IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 Dexamethasone PO 20 mg on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11 and 12 |

[10] | |

| Yes | NDMM |

Combination therapy in AHSCT ineligible patients, with melphalan and prednisone in a 42-day treatment cycle: BTZ IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29 and 32 in cycles 1–4, then once weekly on days 1, 8, 22, 29 in cycles 5–9 Melphalan PO 9 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 Prednisone PO 60 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 Combination therapy in AHSCT eligible patients with dexamethasone in a 21-day treatment cycle: Bortezomib IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 Dexamethasone PO 40 mg on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10 and 11 Combination therapy in AHSCT eligible patients with dexamethasone and thelidomide in a 28-day treatment cycle: Bortezomib IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 Thalidomide PO 50 mg daily on days 1–14, if tolerated then 100 mg on days 15–28, and thereafter further increased to 200 mg daily from cycle 2 Dexamethasone PO 40 mg on days 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 10 and 11 |

|||

| Yes | RRMM |

Monotherapy in a 21-day treatment cycle (optional addition of dexamethasone): Bortezomib IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8 and 11 Dexamethasone PO 20 mg on the day of and the day after each BTZ dose (for patients with PD after 2 cycles or SD after 4 cycles |

[4] [7] |

||

| Yes | NDMM |

Combination therapy in AHSCT ineligible patients, with melphalan and prednisone in a 42-day treatment cycle: BTZ IV/SC* 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29 and 32 in cycles 1–4, then once weekly on days 1, 8, 22, 29 in cycles 5–9 Melphalan PO 9 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 of each cycle Prednisone PO 60 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 of each cycle |

[8] [9] |

||

| Yes | Yes | NDMM |

Combination therapy in AHSCT ineligible patients, with daratumumab, melphalan and prednisone in a 42-day treatment cycle: Daratumumab IV 16 mg/kg weekly in cycle 1, every 3 weeks in cycles 2–9, and every 4 weeks thereafter Bortezomib SC 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on weeks 1, 2, 4, and 5 of cycle 1 and once weekly on weeks 1, 2, 4, and 5 of cycles 2–9 Melphalan PO 9 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 of each cycle Prednisone PO 60 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 of each cycle |

[14] | |

| Yes | Yes | RRMM |

Combination therapy with daratumumab and dexamethasone in a 21-day treatment cycle: Daratumumab IV 16 mg/kg weekly in cycle 1–3, every 3 weeks in cycles 4–8, and every 4 weeks thereafter Bortezomib SC 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of cycle 1–8 Dexamethasone PO 20 mg on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12 |

[15] | |

| Yes | Yes | RRMM |

Combination therapy with panobinostat and dexamethasone in a 21-day treatment cycle: Panobinostat PO 20 mg on days 1, 3, 5, 8, 10, 12 Bortezomib IV 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 Dexamethasone PO 20 mg on days 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 9, 11, and 12 |

[16] | |

| Carfilzomib | Yes | RRMM |

Combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in a 28-day treatment cycle:

Carfilzomib IV 20/27 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15 and 16 Lenalidomide PO 25 mg on days 1–21 Dexamethasone PO 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 Combination with dexamethasone in a 28-day treatment cycle: Carfilzomib IV 20/56 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15 and 16 Dexamethasone PO 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 22, and 23 |

[12] | |

| Yes | RRMM |

Monotherapy in a 28-day treatment cycle:

Carfilzomib IV 20/27 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 Combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in a 28-day treatment cycle: Carfilzomib IV 20/27 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15 and 16 Lenalidomide PO 25 mg on days 1–21 Dexamethasone PO 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 Combination with dexamethasone in a 28-day treatment cycle: Carfilzomib IV 20/56 mg/m2 on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15 and 16 Dexamethasone PO 20 mg on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 22, and 23 OR Carfilzomib IV 20/70 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 Dexamethasone PO 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15 (all cycles) and 22 (cycles 1–9 only) |

[11] [65] [107] [68] |

||

| No | No | NDMM | None approved yet | - | |

| Ixazomib | Yes | Yes | RRMM |

Combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in a 28-day treatment cycle:

Ixazomib PO 4 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 Lenalidomide PO 25 mg on days 1–21 Dexamethasone PO 40 mg on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 |

[76] [13] |

| No | No | NDMM | None approved yet | - | |

PI: proteasome inhibitor; A: approved; FDA: food and drug administration; EMA: European medicines agency; Ref: reference; RRMM: relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma; BTZ: bortezomib; IV: intravenous; SC: subcutaneous;

when feasible as SC administration is preferable over IV due to lower peripheral neuropathy profile [9]; PO: oral; NDMM: newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; AHSCT: autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

3. Proteasome pathway and proteasome inhibitors with regulatory approvals

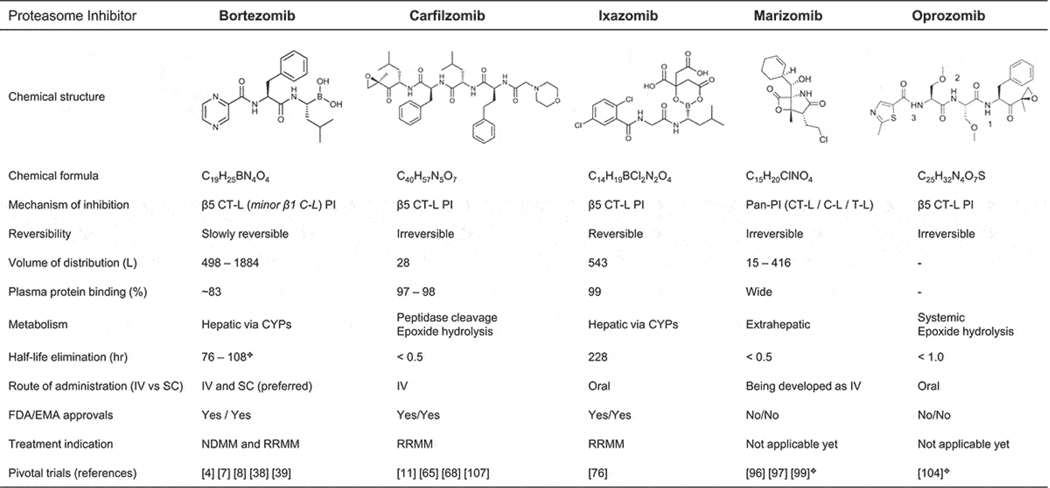

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (UPP) represents one of the principle protein degradation systems that maintains homeostasis of intracellular protein load, and purges the cell of abnormal or misfolded proteins. In doing so, the UPP plays an integral role in numerous cellular processes including cell cycle regulation, proliferation, DNA repair, and drug resistance[17]. Given the extent of intracellular protein load processed by the UPP, its inhibition results in dramatic disruption of protein homeostasis and pathways they regulate, leading to accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins and secondary intracellular stress responses such as cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Malignant plasma cells are considered to have a lower threshold against the stress of intracellular protein accumulation compared to non-neoplastic cells, which makes them particularly susceptible to PIs. The 26S proteasome is an ATP-dependent, multifunctional proteolytic complex that consists of a proteolytic core - the 20S proteasome - positioned between two 19S regulatory complexes. The 20S core particle is a multicatalytic proteinase complex composed of 7 unique subunits in the inner β-rings, three of which contain proteolytic activities, including the chymotrypsin-like (ChT-L, β5), trypsin-like (T-L, β2) and caspase-like (C-L, β1) activities. The ChT-L activity of the β5 subunit, which cleaves downstream of hydrophobic residues, is the rate-limiting step of endoproteolysis. The first non-peptidic PI described was the natural product lactacystin[18], but it was not until years later that the first PIs to achieve regulatory approvals emerged: BTZ, CFZ and IXZ. While all commercially available PIs target the β5 subunit, inhibitory potency and subunit specificity is dependent on the PI dose, and the ultimate functional anti-MM cytotoxicity through proteasome inhibition may also depend on co-inhibition of several subunits simultaneously[19, 20]. Their major PD/PK features are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Major pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic features of common approved and developing proteasome inhibitors.

3.1. Bortezomib

Bortezomib is a first-in-class PI that was initially developed for use as an anti-inflammatory until the recognition of its cytotoxic, growth-inhibitory, and antitumor activities in the late 1990s[21]. Recent reports also suggest BTZ-mediated alterations in the intracellular peptidome contribute to its biological effects[22], as does disruption of the balance between proteasome load and proteasome capacity (recently reviewed in[23]). While it displays a degree of selectivity for the proteasome [24], it was found to inhibit off-proteasome targets including cathepsin G, cathepsin A, chymase, dipeptidyl peptidase II, and HtrA2/Omi, and the latter may contribute to the risk of peripheral neuropathy[25].

3.1.1. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

A modified dipeptidyl boronic acid (Figure 1), BTZ is a selective, potent, reversible inhibitor of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in mammalian cells[26], with the boron atom binding catalytic sites of the 26S proteasome causing anti-tumor effect. The average half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of BTZ across 60 cell lines was 3.8 nM[27]. Recommended BTZ dosing is on a twice-weekly schedule of BTZ at 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11, followed by a 10-day rest period (days 12–21), which is considered a treatment cycle. It is based on PD features for optimal proteasome inhibition from in vivo animal and human cell studies, which showed proteasome activity returning to baseline within 48–72 hours following BTZ dosing[24]. However, based further on prior experience with once weekly BTZ dosing in other malignancies[28], a phase II study of weekly 1.6 mg/m2 I.V. BTZ in RRMM was conducted: similar toxicity profiles and response rates were observed, including a median progression free survival (PFS) of 9.6 months, and 1-year and 2-year overall survival (OS) rates of 75% and 51%, respectively[29]. Lastly, a phase III trial in NDMM where BTZ-melphalan-prednisone (VMP)-thalidomide followed by maintenance BTZ-thalidomide versus VMP resulted in abundant neurologic toxicities, leading to once-weekly instead of twice-weekly BTZ dosing adjustment in both arms, showed that the schedule change produced improvements in safety without affecting the efficacy, further demonstrating the feasibility of once weekly dosing[30].

Highly dynamic shifts in various pharmacokinetic parameters, including area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC), drug clearance (CL), volume of distribution (Vdss), maximum observed plasma drug concentration (Cmax), intravenous (I.V.) versus SC delivery, time to Cmax (tmax) and terminal half-life (t1/2) that are observed following variations in dosing level, routes of administration, as well as single versus repeat-dosing have been described extensively previously[9, 31, 32, 33], and are beyond the scope of the current review. The pharmacokinetic profile of BTZ was first studied with I.V. administration, where administration of the 1.3 mg/m2 dose defined the median Cmax of 509 ng/ml (range, 109–1300 ng/ml) in 8 patients with MM whose creatinine clearance (CrCl) ranged from 31–169 ml/min[27]. Bortezomib is 83% bound to human plasma proteins at these therapeutic concentrations and higher (range 100 – 1,000 ng/mL), with a large mean Vdss, ranging from approximately 498 to 1884 L/m2 after single or repeat-dose administrations of 1 or 1.3 mg/m2. This facilitates its extensive peripheral tissue distribution[32]. The mean t1/2 of BTZ after multiple dosing ranged from 40–193 hours for the 1 mg/m2 dose, and 76–108 hours after the 1.3 mg/m2 dose. Repeat BTZ dosing reduces the mean total body clearances from 102 and 112 L/h following the first doses of 1 and 1.3 mg/m2, respectively, to 15–32 L/h following subsequent administration of the 1 and 1.3 mg/m2 doses, respectively[32, 33].

With the introduction of a SC formulation in animal studies which showed comparable bioavailability and extent and duration of whole blood proteasome inhibition, a prospective comparison of PK and PD for the I.V. and SC administrations in MM was conducted[9]. The overall 20S proteasome inhibition was similar, and an improved safety profile for the SC mode was identified [significantly less common peripheral neuropathy (PN) of any grade (G), including G ≥ 2/3] resulting in a regulatory approval (Table 2) and adoption of the SC delivery route in MM practice [9, 31].

A series of in vitro human metabolism studies in liver microsomes and cDNA-expressed cytochrome P450 (CYP) isozymes indicated that the major metabolic pathway for BTZ degradation involves hepatic oxidative deboronation by multiple common CYP enzymes[34, 35, 36]. In vivo BTZ exposure was not affected significantly by age, body surface area (BSA) or body mass index[33]. Similarly, an early phase study in adult cancer patients with various degrees of renal impairment found that decreased creatinine clearance (CrCl) had no effect on BTZ PK/PD[37]. Lastly, a phase I study of BTZ in various degrees of hepatic impairment showed that AUClast was increased by ~60% on day 8 in patients with moderate hepatic [defined as bilirubin >1.5–3x upper limit of normal (ULN)] or severe hepatic impairment (defined as bilirubin >3xULN)[38]. Consequently, patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment require a reduced BTZ starting dose of 0.7 mg/m2.

3.1.2. Clinical efficacy, safety, tolerability and toxicity

Bortezomib was first studied in phase I trials of patients with advanced solid tumor and refractory hematologic malignancies[3, 39]. In nine fully assessable patients with heavily pre-treated plasma cell dyscrasias who completed at least one cycle of therapy, there was one complete response (CR) and a reduction in paraprotein levels and/or marrow plasmacytosis in eight others[3]. Two subsequent phase II trials involved 246 evaluable patients with RRMM: in the first, BTZ was given at doses of 1.0 and 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly for 2 weeks, every 3 weeks, yielding a single agent overall response [including minimal/minor response (MR) added to CR + partial response (PR)] of 33% and 50% in the two doses, respectively (when given in combination with dexamethasone, response improved to 44% and 62%, respectively)[7]. In the other, BTZ was given at a single dose of 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 in a 21-day cycle, giving an overall response of 35%, a median OS of 16 months and a median duration of response (DOR) of 12 months[4]. Grade 3 adverse events (AEs) included thrombocytopenia (28%), fatigue (12%), PN (12%), and neutropenia (11%), and with low rate of G4 events[4]. In the international, phase III trial of BTZ given at 1.3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 versus high-dose dexamethasone in RRMM patients who had received up to three lines of therapy, the overall response rate (ORR) - defined as ≥ PR - for the two groups was 38% and 18%, respectively (p < 0.001), with a hazard ratio (HR) for OS with BTZ of 0.57 (p = 0.001)[40]. Grade 3 AEs were reported in 61% of patients receiving BTZ and in 44% of those receiving dexamethasone, with similar rates of G4 AEs and serious AEs[40]. With a median follow-up of 22 months, the median OS was 6 months longer in the BTZ arm despite substantial crossover from dexamethasone to BTZ (29.8 versus 23.7 months)[41], leading to the FDA approval of BTZ in RRMM.

In NDMM, BTZ combinations were tested in both autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (AHSCT)-ineligible and -eligible patients in two phase III trials[8, 42]. In the first, the addition of BTZ to the MP doublet improved ORR from 35% to 71% (p<0.001) among the arms[8], with the median OS not reached in the triplet versus 43 months in the MP arm on a follow-up evaluation (3-year OS rates 68.5% versus 54.0%, respectively)[43]. In the second, addition of BTZ to the lenalidomide/dexamethasone (Rd) doublet improved the ORR from 72% to 82% (p = 0.02), lengthened the median PFS from 30 to 43 months, and raised median OS from 64 to 75 months (HR 0.709, p = 0.025)[42]. Both studies demonstrated an acceptable risk-benefit profile (Table 1). In Europe, VTD is used as a standard induction therapy for AHSCT eligible MM patients, where it significantly improved the combined CR and near-CR rates versus VD (31% versus 11%)[44]. Lastly, BTZ was found to be well tolerated and effective as a maintenance, where it led to an improved CR and superior PFS and OS after induction and maintenance post-AHSCT[45], and improved PFS and OS in the treatment of high-risk NDMM with del(17p) following BTZ-based induction and maintenance[45, 46].

3.2. Carfilzomib

A search for a more potent, irreversible inhibitor with alternate PK/PD properties to BTZ resulted in the second-generation PI carfilzomib. A tetrapeptide-epoxyketone analog (Figure 1) of epoxomicin, it contains a peptide segment responsible for high affinity binding to the proteasome, and an epoxyketone pharmacophore with selectivity for the chymotrypsin-like activity of the β5 subunit of the 20S proteasome[47, 48]. It was first discovered during in vivo antitumor screening, where it exhibited activity against B16 melanoma cells[49], and it became the first irreversible PI to gain FDA approval for the treatment of MM.

3.2.1. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

In preclinical in vitro analysis, CFZ demonstrated more cytotoxicity than BTZ following brief treatments that mimicked the in vivo pharmacokinetics of both molecules, with hematologic tumor cells exhibiting the greatest sensitivity[48]. Furthermore, I.V. antitumor efficacy on 2 consecutive days was stronger than that of BTZ administered on its clinical dosing schedule. Preclinical studies in rats and monkeys demonstrated that CFZ achieved extensive and rapid tissue distribution, except for the inability to penetrate to the central nervous system (CNS) space[48, 50]. Based on a 20 mg/m2 dose, Vdss is 28 liters (L)[51]. In rats, CFZ is largely metabolized and cleared from the circulation by biliary and renal excretion (urine ~25% as metabolites and <1% as parent drug; feces <1% as parent drug), and its rapid elimination is mediated primarily by metabolism via peptidase cleavage and epoxide hydrolysis[50]. The Cmax and AUC exposure to CFZ increased proportionally from 2–4 mg/kg dose, but less so in the 4–8 mg/kg range, with the major metabolites (M14, M15, and M16) mainly inactive as PIs, leaving less than 1% of CFZ excreted intact[50]. These PK and PD properties give rise to the favorable safety profile and rapid elimination, which minimizes systemic exposure to CFZ and reduces potential off-target toxicities, possibly accounting for the favorable safety profile. These properties are distinct from those of reversible inhibitors such as BTZ, which may need to depend on sustained drug exposure at or above the therapeutic concentration for desired efficacy. Due to its irreversible mechanism of target inhibition, potent proteasome inhibition (≥80%) persists in blood after CFZ is cleared systemically, allowing for higher dosing[52]. In a PK and metabolic profiles study of CFZ in patients with solid tumors or MM, CFZ plasma concentration decreased in a biphasic manner after administration at 20 mg/m2 I.V., with a systemic clearance greater than hepatic blood flow, and a t1/2 <30 mins[53]. Extensive protein bounding in the plasma (97.6–98.2%) was independent of CFZ concentration across 21.6–7841 ng/ml, and was not affected by the status of renal function[53]. In a phase II study where CFZ was well tolerated, the PK and safety of CFZ were similarly unaffected by the degree of baseline renal impairment, including in patients on dialysis[54]. Unlike with BTZ, presence of CYP inhibitors did not affect the rate of CFZ metabolism in human hepatocytes, further suggesting that CYP enzymes play only a minor role in CFZ clearance[53]. Carfilzomib similarly did not show clinically significant drug-drug interactions[55]. In contrast to BTZ, overexpression of the ABCB1 P-glycoprotein in MM cells was found in one study to lead to reduced proteasome-inhibiting activity of CFZ due to drug efflux[56, 57].

3.2.2. Clinical efficacy, safety, tolerability and toxicity

One of the early phase I CFZ studies in RRMM administered escalating I.V. doses (ranging from 1.2–27 mg/m2) on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, and 16 every 28 days, without reaching the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), which defined the consecutive day I.V. administration for three consecutive weeks, with one week off. At the 20 mg/m2 dose, one case of G3 acute renal failure (ARF) occurred, while one case of G3 hypoxia was confirmed in the final analysis in the 27 mg/m2 cohort[58]. After this, two early phase studies in RRMM combined CFZ with IMiDs and steroids. The first involved the addition of Rd, where patients received CFZ and lenalidomide at different escalating doses, and dexamethasone at a fixed dose (KRd), yielding a 2.5% stringent CR (sCR), 32.5% very good partial response (VGPR) and 27.5% PR rate[59]. The second assessed addition of pomalidomide and dexamethasone to patients refractory to prior lenalidomide: the MTD of CFZ at the 20/27 mg/m2 dosing resulted in a 66% ORR (16% VGPR, 34% PR and 16% MR) and hematologic AEs in ≥60% of all patients[60]. Carfilzomib was also evaluated in early phase studies of similar combinations in NDMM patients. One study allowed subsequent AHSCT for eligible patients after 4 cycles of KRd, followed by maintenance KRd, and single-agent lenalidomide off protocol after completion of 24 cycles[61]. Phase II CFZ dosing at 36 mg/m2 resulted in rapid and improving responses over time (for patients completing at least 8 cycles: 78% near CR and 61% sCR), with G 3/4 toxicities including hypophosphatemia (25%), hyperglycemia (23%), anemia (21%), thrombocytopenia (17%), and neutropenia (17%) and only G 1/2 PN (23%); after a median follow-up of 13 months, 2-year PFS was 92%[61]. Alternative combinations of carfilzomiob with fixed dose cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (KCyd) were also tested in NDMM patients, with the CFZ MTD dose of 20/36 mg/m2, resulting in a ≥VGPR rate of 59% after 4 cycles of therapy, and a 2-year PFS and OS of 76% and 96%, respectively. Common ≥G3 AEs were lymphopenia (38%), neutropenia (23%) and anemia (20%), without CFZ-attributable neuropathy[62].

Further experiences with single-agent phase II CFZ studies in RRMM with our without prior BTZ exposure[11, 63, 64] ultimately lead to the large randomized phase III trial which tested KRd versus Rd (CFZ 20/27 mg/m2, lenalidomide 25 mg, dexamethasone 40 mg). The primary end point, PFS, was significantly improved (median 26.3 versus 17.6 months; HR 0.69; P=0.0001), and AEs G ≥3 (grouped terms; KRd versus Rd) included dyspnea (2.8% versus 1.8%), cardiac failure (3.8% versus 1.8%), ischemic heart disease (3.3% versus 2.1%), hypertension (4.3% versus 1.8%), and ARF (3.3% versus 3.1%); treatment discontinuation rates owing to AEs were similar (15.3% versus 17.7%)[65]. The subsequent follow-up analysis of efficacy and safety additionally demonstrated improvement in median OS (48.3 versus 40.4 months, HR 0.79; P = 0.0045), and an overall G ≥3 AE rates of 87.0% versus 83.3%: ARF (3.8% versus 3.3%), cardiac failure (4.3% versus 2.1%), ischemic heart disease (3.8% versus 2.3%), hypertension (6.4% versus 2.3%), hematopoietic thrombocytopenia (20.2% versus 14.9%), and PN (2.8% versus 3.1%)[66].

Lastly, based on prior preclinical safety results that suggested a longer, 30-min infusion may be better tolerated and permit administration of higher doses than 2–10-minute infusions[50], a multicenter, single-arm, phase I/II study evaluated once-weekly Kd in RRMM patients after 1–3 prior therapies[67]. The CFZ MTD dose of 70 mg/m2 in 104 patients with 1 median prior number of cycles resulted in G≥3 AEs including fatigue (11%) and hypertension (7%); ORR was 77% and median PFS was 12.6 months[67]. A follow up phase III study that compared the effect of once weekly Kd (70 mg/m2) versus twice weekly Kd (20/27 mg/m2) dosing on PFS in patients with RRMM found that weekly dosing significantly prolonged PFS (11.2 versus 7.6 months, HR 0.69, p=0.0029) with comparable overall safety[68](Table 1), leading to FDA approval for this administration. Lastly, pooled analysis of KCyd induction, where CFZ was given at either 70 mg/m2 once-weekly or 36 mg/m2 twice-weekly, followed by CFZ maintenance, demonstrated safety and effectiveness among the two administrations, while weekly dosing provided a more convenient schedule[69].

There is a concern that phase 1 studies may be under-detecting cardiovascular adverse events (CVAEs) in CFZ-treated patients, as illustrated by a meta-analysis of over 2500 patients in 24 trials. This study identified an 8.2% rate of grade 3 and higher CVAE (phase II or III studies and CFZ doses of 45 mg/m2 or higher were associated with a greater incidence of high-grade CVAEs)[70].

3.3. Ixazomib

The pursuit of proteasome inhibitors with potentially increased efficacy and reduced toxicity paved the path towards development of IXZ, which was introduced through a large-scale screening of boron-containing PIs with physiochemical properties distinct from BTZ[71]. The first oral PI to enter clinical practice, IXZ is a citrate ester of boronic acid (Figure 1) and belongs to the same structural class and acts through the same mechanisms as BTZ.

3.3.1. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

Understanding of the exact mechanistic targets of IXZ is evolving as prior reports implied preferential inhibition of the β5 chymotrypsin-like proteasome subunit and, at high concentrations, inhibition of other proteolytic sites such as the β1 caspase-like and β2 trypsin-like subunits can be seen[72]. However, a more recent report suggests that IXZ in fact displays a slightly higher preference for the β1c/i over β5c/i subunit[20]. IXZ has an IC50 of 3.4 nmol/L, and a proteasome dissociation t1/2 six times shorter than that of BTZ, implying a wider tissue distribution[72]. It is usually delivered weekly on days 1, 8, and 15 of every 28-day cycle. Ixazomib was studied in several phase I trials, where the main PK features relating to absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion were obtained. Ixazomib is rapidly absorbed, with a Tmax of roughly 1 hour after dosing[73], and a Cmax of 0.11 μg/ml at the most common dose of 4 mg weekly[74]. These studies also showed that BSA did not influence IXZ clearance or systemic exposure, allowing the transition from the BSA-scaled, to fixed dosing[6]. In it, the AUC increased proportionally over a dose range of 0.2–10.6 mg with a dose-linear model[6]. However, a food interaction study demonstrated an AUC reduction by 28% after a high-fat meal [23], decreasing both the rate and extent of IXZ absorption, which is why it is recommended that it is taken on an empty stomach (no food ingested for at least 2 hours before and 1 hour after drug administration)[75].

Large population PK analyses of IXZ, including data from the phase III study[76] to inform labelling, demonstrated first-order linear absorption with an absolute oral bioavailability of 58%[77]. Clinical PK of I.V. and oral IXZ from four phase 1 monotherapy trials, as well as data from late phase population studies, demonstrated that IXZ is 99% bound to plasma proteins (the extent of protein binding is unaffected by renal or hepatic function), explaining the rapid absorption and the basis for a terminal t1/2 elimination of 9.5 days[78]. The steady-state Vdss of IXZ is large, and was estimated to be 543 L based on the population PK model[77], leading to wide tissue distribution[72]. Ixazomib citrate is a prodrug that, upon entry to aqueous medium such as plasma, rapidly hydrolyzes to its biologically active form, IXZ[6]. In vitro studies of cytochrome P450 (CYP) isozymes showed that several major human CYP isozymes were involved in hepatic metabolism, but with no specific CYP isozyme predominating[79]. Given hepatic metabolism, a study targeting patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment (total bilirubin >1.5xULN) was conducted in patients with solid tumors to reliably characterize PK and obtain posology recommendations for IXZ in circumstances of hepatic impairment. Blood samples for single-dose PK characterization collected over 336 hours post-dosing with 4, 2.3, or 1.5 mg in normal hepatic function, or moderate or severe impairment, respectively, showed that unbound and total systemic exposures of IXZ was 27% and 20% higher in moderate/severe hepatic impairment as compared to normal hepatic function[80]. As such, a reduced IXZ starting dose of 3 mg was recommended for patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment. Excretion of IXZ was studied in a two-part phase I study of 14C-IXZ where blood, urine, and fecal samples were collected and studied via accelerator mass spectrometry to measure the amount of total excreted radioactive drug in seven patients with advanced solid tumors or lymphoma[81]. In the evaluable patients, cumulative recovery of IXZ-related radioactivity was 83.9% in urine and feces combined (urine predominant, with 62.1%). It is worth noting that 3.23% of the administered drug was recovered in the urine as unchanged IXZ during the 168-hour post-dose collection interval, suggesting minimal renal clearance of IXZ of 0.119 L/h (6.4% of the total body clearance)[81]. These findings showed that IXZ is extensively metabolized and that metabolism is expected to be the major clearance mechanism for IXZ[79]. A separate study was conducted of single-dose IXZ PK in cancer patients with normal renal function [CrCl ≥90 ml/min], severe renal impairment [(RI) CrCl <30 ml/min], or end-stage renal disease requiring hemodialysis (ESRD)[82]. After a single 3 mg dose, while IXZ remained highly bound to plasma proteins (~99%) in all groups, unbound and total systemic exposures of IXZ were 38% and 39% higher, respectively, in severe RI/ESRD patients versus patients with normal renal function. Total IXZ concentrations were similar in pre- and post-dialysis samples, arguing that IXZ can be administered without regard to hemodialysis schedule[82]. Results of this study supported a reduced IXZ dosing of 3 mg in patients with severe RI/ESRD.

3.3.2. Clinical efficacy, safety, tolerability and toxicity

In the phase I study with RRMM patients, the MTD of 2.0 mg/m2 (an equivalent fixed dose of 3.7 mg) yielded a 76% stable disease (SD) or better rate (15% PR)[83]. Most common drug-related G ≥3 AEs were thrombocytopenia (37%) and neutropenia (17%) and dermatologic toxicities (8%). Similar response rates with a slightly higher MTD of 2.97 mg/m2 were observed in another phase I study in the same setting[84]. Here, most relevant G ≥3 drug-related AEs were thrombocytopenia (28%), neutropenia (13%), diarrhea (13%), lymphopenia (9%), and nausea (9%). Ixazomib was subsequently tested in two oral doses of 4 and 5.5 mg on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle in combination with dexamethasone (Id) for patients with RRMM: both combinations of Id were effective, and while higher dosing of 5.5 mg seemed to induce more responses (ORR: 38 versus 52%), it also yielded a higher rate of G ≥3 AEs (21 versus 54%)[85].

The first phase III study tested the triplet of IXZ in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone (IRd) versus Rd in RRMM patients: it showed a better ORR (78 versus 72%, p = 0.04), and a longer median PFS in favor of the triplet (21 versus 15 months, p = 0.01), with the median OS not reached in either group (Table 1)[76]. Discontinuation rates due to toxicity were 17% in the triplet versus 14% in the doublet arms (2% of patients in both arms had G3 events), and comparable rates of painful neuropathy were observed in the two (4% versus 3% respectively). Overall G ≥3 AEs included thrombocytopenia (19 versus 9%), rash (7 versus 4%) and diarrhea (6 versus 3%). Two early phase studies tested IRd in the NDMM population: the first resulted in an ORR of 92% (CR rate of 27%) and an estimated 2-year PFS of 66%[86] and G ≥3 AEs reported in 63% of patients, including skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (17%), neutropenia (12%), and thrombocytopenia (8%). In the second, the same triplet combination which was used both during induction and post-AHSCT consolidation resulted in an ORR of 81% (CR rate 12% prior to AHSCT increased to 38% post AHSCT, all the way to 44% following consolidation phase)[87]. In addition, IXZ was also tested in a phase I/II study of twice-weekly dosing schedule on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of a 21-day cycle in combination with Rd in patients with NDMM: the confirmed ORR was 94% (68% ≥VGPR; 24% CR), median PFS 24.9 months with a median DOR of 36.9 months that also deepened over time[88]. This schedule, however, was associated with greater toxicity compared with weekly IRd dosing in this setting (G ≥3 AEs occurred in 64% of patients).

In the maintenance phase, IXZ was combined with lenalidomide after AHSCT in a phase II trial with an estimated 2-year PFS of 83%, where G ≥3 AEs included infections (26%), neutropenia (23%), rash (12%) and thrombocytopenia (11%)[89]. Lastly, IXZ’s favorable route of administration, weekly scheduling, and good safety/efficacy profile launched 2 phase III trials of single-agent IXZ as maintenance therapy in NDMM patients who received (TOURMALINE-MM3)[90], and those who have not undergone AHSCT (TOURMALINE-MM4)[91]. The first just reported a 28% reduction in the risk of progression or death with IXZ versus placebo (median PFS 26.5 versus 21.3 months; HR 0.72, p=0.0023)[90].

4. Non-FDA approved proteasome inhibitors of interest

4.1. Marizomib

Marizomib (MRZ) is a PI derived from a marine actinomycete (Figure 1) and, in contrast to the current FDA approved inhibitors, potently inhibits all 3 major catalytic activities of the 20S core particle[92, 93]. It internalizes rapidly to covalently bind to all three active enzymatic sites[94], leading to irreversible proteasome inhibition in vitro and in vivo[95]. Marizomib has a short t1/2 (< 30 mins), with high Vdss (∼15–416 L) and CL of ∼0.9–22 L/mins[96]. Marizomib has been studied in several phase I trials in patients with MM (Table 1). In the first phase I study, patients with RRMM who received and were refractory to prior CFZ (prior AHSCT was allowed) were tested with either once-weekly infusions of MRZ on days 1, 8, and 15 of 4-week cycles (dose ranges of 0.025–0.7 mg/m2, infused over 1 or 10 min) or twice-weekly infusions on days 1, 4, 8, and 11 of 3-week cycles (dose ranges of 0.015–0.6 mg/m2, infused over 60 or 120 min, with concurrent dexamethasone allowed). The most common (>20% of patients) related AEs were fatigue, headache, nausea, diarrhea, dizziness, and vomiting; 6 (9%) patients achieved clinical benefit (defined as minimal response or better), including 5 PRs (1 patient on schedule A and 4 on schedule B; 3 of these 4 patients received concomitant dexamethasone)[97]. In the second phase I study of patients with advanced malignancies including RRMM, MTD dosing previously identified with the weekly and twice-weekly schedule was employed in combination with low-dose dexamethasone: the most common (>25% of patients) related AEs were fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, and infusion site pain (weekly dosing); and fatigue (twice-weekly dosing); ORR was 11% in 27 efficacy-evaluable RRMM patients who received twice-weekly dosing (1 VGPR, 3 PR, 4 MR, and 12 SD)[96]. Further analysis of the PD effects of MRZ on subunit-specific proteasome activity suggested that initial potent inhibition of ChT-L activity led to a compensatory hyperactivation of the C-L and T-L subunits that was overcome by repeated dosing with MRZ, ultimately resulting in robust pan-proteasome inhibition within 2 dosing cycles in the majority of patients[98]. The last study evaluated MRZ with pomalidomide and low dose dexamethasone in RRMM patients who had received prior lenalidomide and BTZ, and showed overall response and clinical benefit rates (≥MR) of 53% and 64%, respectively, with G≥3 AEs including neutropenia (29%), pneumonia (11%), anemia (11%) and thrombocytopenia (11%)[99]. Lastly, MRZ was found to penetrate the CNS, and has demonstrated clinical efficacy in RRMM patients with CNS involvement, making it potentially appealing in this unmet need population[100].

4.2. Oprozomib

Oprozomib (OPZ) is an oral, second generation, selective and irreversible tripeptide PI with an epoxyketone subunit (Figure 1), which inhibits the N-terminal threonine active site of the chymotrypsin-like subunit of the constitutive proteasome and immunoproteasome[101, 102]. Developed to improve enteric absorption, it demonstrated a very short t1/2 (<1 hour) and high systemic clearance, which together with its selectivity and irreversibility allows exploration of higher doses[103]. In the first-in-human dose-escalation study of OPZ in 44 patients with advanced solid tumors where the drug was delivered in escalating once-daily or split dosing on days 1–5 of 14-day cycles, common adverse events (all Gs) included nausea (91%), vomiting (86%), and diarrhea (61%), with 10 (23%) of 38 evaluable patients showing SD as their best response[104]. In the first early phase RRMM study which investigated once-daily dosing on days 1–5 and 15–19 (i.e. 5/14 schedule), or dosing on days 1, 2, 8, 9, 15, 16, 22, 23 (i.e. 2/7 schedule), common G ≥3 AEs included diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting, with an ORR of 33% and 37% in 2/7 and 5/14 schedules respectively[105]. In the second RRMM study of similarly dosed OPZ in combination with pomalidomide and dexamethasone, the most common G ≥3 AEs were anemia and diarrhea (each 24%) in the 2/7 schedule, with ≥PR in 2 patients (50%) in the 5/14, and 10 patients (59%) in the 2/7 schedule[106].

5. Conclusions

Based on inherent genetic instability and rapid proliferation rates, malignant cells including MM are inevitably dependent on proteasome activity to ameliorate the intracellular stress of misfolded or damaged proteins. This has been exploited by the development of a series of clinical grade PIs over the past two decades. Three of them are FDA/EMA approved (BTZ, CFZ, IXZ) for clinical practice, and remain an integral part of many MM regimens for the management of all phases of this disease. Simplified and convenient modes and schedules of delivery, including improved side effect profiles, have streamlined the delivery of PIs in urban and rural, and academic and community settings. Treatment with PIs is usually well tolerated, with acceptable and manageable AEs, though attention is warranted in specific patient populations with underlying renal, hepatic, or cardiac insufficiencies. Cardiac events such as congestive heart failure, pulmonary edema or hypertension, ejection fraction decrease and ischemia may be increased in CFZ treated patients, requiring careful patient monitoring and prompt management of any cardiac complications. Resumption of CFZ following any cardiac G ≥3 event requires a nuanced benefit/risk assessment. Proteasome inhibitors are being investigated with several ongoing studies in triplet and quadruplet combinations that are incorporating immunotherapies. Regulatory expansion for CFZ and IXZ in the NDMM, and IXZ in the maintenance setting is likely over the next decade, while MRZ as the only pan-PI with irreversible binding holds promise, particularly in the settings of CNS spread and innate and/or acquired PI resistance.

6. Expert opinion

Several advancements and insights regarding PIs have materialized over the last decade: (1) arrival of the first oral PI IXZ which boasts a more convenient route of administration and an improved toxicity profile, resulting in improved quality of life and patient compliance; (2) relative lack of PN with CFZ and IXZ which was more commonly associated with BTZ; (3) approval of the less frequent and more convenient weekly CFZ dosing, though efficacy and safety remains largely unknown in the triplet combinations which tend to be preferred in the management of RRMM; (4) CFZ was approved for RRMM with proven efficacy as a single agent, or in doublet and triplet combinations, broadening its application to a wide range of fit and frail patients, however, manifestations of composite CFZ-related CVAE merit attention[65, 70, 107]; (5) clinical efficacy, additive and cumulative benefit of all PIs seems especially notable in the outcomes of high-risk MM patients such as those with del(17p) and t(4;14); (6) the arrival of viable all-oral combination therapy that maintains efficacy during long-term management for what has for many patients become a long-term chronic condition; and (7) emergence of novel pan-PIs such as MRZ that may exert superior clinical activity in comparison with other PIs characterized by reversible binding which does not promote their accumulation or monospecificity for the ChT-L site.

Several ongoing trials – with CFZ and IXZ in particular – in novel triplet and “quad” combinations in penta-refractory RRMM patients (experienced progression while receiving lenalidomide, BTZ, pomalidomide, CFZ, and daratumumab) are currently ongoing and/or accrual has been completed with the data maturing. These studies which are incorporating other IMiD, immunotherapy and novel agents such as selinexor (first-in-class, oral, irreversible selective inhibitor of nuclear export[108]) will likely alter the standards of practice for the management of both NDMM and RRMM, including the most optimal consolidation and/or maintenance strategies post-AHSCT. Marizomib is an upcoming PI of interest as it remains attractive due to its pan-proteasome inhibition, which may address PI resistance in some cases, and potential efficacy in an unmet need MM population with CNS disease spread.

However, significant areas of concern that remain are the empiric use of PIs, as no biomarkers of sensitivity or resistance have been clinically validated that can prospectively identify patients who are likely to respond to PIs. In addition, primary and secondary PI resistance, which modulate MM proteasome capacity, are problems that directly influence treatment responses and outcomes. At present, there is no clinically available assay that predicts the volume of PI-resistant disease at diagnosis[109], though some recent efforts including the use of gene expression signatures to predict PI responsiveness show promise[110, 111]. As we continue to build on an increasing appreciation of genetic and developmental heterogeneity in MM, biomarker-based approaches could allow identification of patients who are less likely to benefit from PI treatment towards more effective alternative therapies, thus lowering treatment-related toxicity, costs of healthcare, and inconvenience. Moreover, a biomarker predicting drug sensitivity could be exploited to maximize the benefits of upfront therapy in sensitive patients. To this extent, persistent implication of several signaling pathways, including NF-κB, EGFR-JAK-STAT[112] and MET-MAPK may lead to development of more effective strategies against PI resistance in clinical practice, as well as development of biomarkers that for the first time may inform the targeted and rational frontline treatment of MM patients.

Article highlights.

Proteasome inhibitors (PIs) with regulatory approvals include bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib, while others, such as marizomib and oprozimib, also show promise.

Due to a significantly lower rate of peripheral neuropathy of any grade, subcutaneous versus intravenous delivery of bortezomib is considered a preferred standard of practice.

Carfilzomib has the potential for superior potency and efficacy with decreased neuropathy, but cardiovascular adverse events may be increased and require careful patient monitoring.

In the setting of renal failure, bortezomib or carfilzomib do not require dose adjustment while ixazomib does, and all three drugs need dose adjustment in patients with hepatic impairment.

No validated biomarkers of PI sensitivity and/or resistance have been prospectively validated, though recent gene expression signature approaches in this area show promise.

PIs remain cornerstone agents in the treatment of all phases of multiple myeloma, including newly approved “quadruplet” regimens that incorporate immunotherapies.

Funding

This paper was funded by the National Cancer Institute (P50 CA142509, R01s CA184464 and 194264, and U10 CA032102), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (SCOR-12206-17), and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation through support to RZ Orlowski.

Declaration of Interest

M Baljevic has served on advisory boards for Amgen, Inc., which markets carfilzomib, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, which markets bortezomib and ixazomib, and has served in an advisory capacity to Karyopharm Therapeutics and Cardinal Health. RZ Orlowski has served on advisory boards for Amgen, Inc., Celgene Corporation, GSK Biologicals, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Juno Therapeutics, Kite Pharma, Legend Biotech, Molecular Partners, Servier, and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and received research funding from BioTheryX. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in, or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Footnotes

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

References

* of importance, ** of considerable importance

- 1.Palumbo A, Giaccone L, Bertola A, et al. Low-dose thalidomide plus dexamethasone is an effective salvage therapy for advanced myeloma. Haematologica. 2001. Apr;86(4):399–403. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baljevic M, Holstein SA. Present and Future of Immunotherapy in the Management of Multiple Myeloma. J Oncol Pract. 2018. Jul;14(7):403–410. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00111. PubMed PMID: 29996070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orlowski RZ, Stinchcombe TE, Mitchell BS, et al. Phase I trial of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in patients with refractory hematologic malignancies. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4420–7. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:2609–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030288. PubMed PMID: . **One of the two key phase II studies that led to the first approval of bortezomib in multiple myeloma.

- 5.Pautasso C, Bringhen S, Cerrato C, et al. The mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, and clinical efficacy of carfilzomib for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013. Oct;9(10):1371–9. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2013.817556. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salvini M, Troia R, Giudice D, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug evaluation of ixazomib citrate for the treatment of multiple myeloma. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2018. Jan;14(1):91–99. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2018.1417388. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jagannath S, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. A phase 2 study of two doses of bortezomib in relapsed or refractory myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2004. Oct;127(2):165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05188.x. PubMed PMID: . *The second phase II study that led to the first approval of bortezomib.

- 8. San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:906–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801479. PubMed PMID: . *A randomized study that led to the first approval of bortezomib for newly diagnosed patients with symptomatic myeloma.

- 9.Moreau P, Coiteux V, Hulin C, et al. Prospective comparison of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with multiple myeloma. Haematologica. 2008. Dec;93(12):1908–11. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13285. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velcade (bortezomib). An overview of Velcade and why it is authorised in the EU]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/EPAR/velcade

- 11. Siegel DS, Martin T, Wang M, et al. A phase 2 study of single-agent carfilzomib (PX-171–003-A1) in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;120:2817–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-425934. PubMed PMID: . **Report of study data which supported the fuirst approval of carfilzomib for relapsed/refractory myeloma.

- 12.Kyprolis (carfilzomib). An overview of Kyprolis and why it is authorised in the EU]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/medicines/human/EPAR/kyprolis

- 13.Ninlaro (ixazomib). An overview of Ixazomib and why it is authorised in the EU]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/ninlaro

- 14. Mateos MV, Dimopoulos MA, Cavo M, et al. Daratumumab plus Bortezomib, Melphalan, and Prednisone for Untreated Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2018. Feb 8;378(6):518–528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1714678. PubMed PMID: . *First randomized trial demonstrating the efficacy of daratumumab in combination with a proteasome inhibitor-based regimen for newly diagnosed myeloma patients.

- 15. Palumbo A, Chanan-Khan A, Weisel K, et al. Daratumumab, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(8):754–766. doi: doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606038. PubMed PMID: . **Phase III trial demonstrating the efficacy of adding daratumumab to a bortezomib-based regimen in relapsed or refractory myeloma.

- 16.San-Miguel JF, Hungria VT, Yoon SS, et al. Panobinostat plus bortezomib and dexamethasone versus placebo plus bortezomib and dexamethasone in patients with relapsed or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014. Oct;15(11):1195–206. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70440-1. PubMed PMID: 25242045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Biologic impact of proteasome inhibition in multiple myeloma cells--from the aspects of preclinical studies. Semin Hematol. 2012. Jul;49(3):223–7. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2012.04.006. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3383768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fenteany G, Standaert RF, Lane WS, et al. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science (New York, NY). 1995;268:726–31. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Bruin G, Xin BT, Kraus M, et al. A Set of Activity-Based Probes to Visualize Human (Immuno)proteasome Activities. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016. Mar 18;55(13):4199–203. doi: 10.1002/anie.201509092. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Besse A, Besse L, Kraus M, et al. Proteasome Inhibition in Multiple Myeloma: Head-to-Head Comparison of Currently Available Proteasome Inhibitors. Cell Chem Biol. 2019. Mar 21;26(3):340–351 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.11.007. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez-Serrano I Success in translational research: lessons from the development of bortezomib. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006. Feb;5(2):107–14. doi: 10.1038/nrd1959. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelman JS, Sironi J, Berezniuk I, et al. Alterations of the intracellular peptidome in response to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053263. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3538785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manasanch EE, Orlowski RZ. Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017. Jul;14(7):417–433. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.206. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5828026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams J, Palombella VJ, Sausville EA, et al. Proteasome inhibitors: a novel class of potent and effective antitumor agents. Cancer Res. 1999. Jun 1;59(11):2615–22. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arastu-Kapur S, Anderl JL, Kraus M, et al. Nonproteasomal targets of the proteasome inhibitors bortezomib and carfilzomib: a link to clinical adverse events. Clin Cancer Res. 2011. May 1;17(9):2734–43. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1950. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams J, Behnke M, Chen S, et al. Potent and selective inhibitors of the proteasome: dipeptidyl boronic acids. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998. Feb 17;8(4):333–8. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bross PF, Kane R, Farrell AT, et al. Approval summary for bortezomib for injection in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004. Jun 15;10(12 Pt 1):3954–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0781. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Papandreou CN, Daliani DD, Nix D, et al. Phase I trial of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumors with observations in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004. Jun 1;22(11):2108–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.106. PubMed PMID: 15169797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hainsworth JD, Spigel DR, Barton J, et al. Weekly treatment with bortezomib for patients with recurrent or refractory multiple myeloma: a phase 2 trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. Cancer. 2008. Aug 15;113(4):765–71. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23606. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bringhen S, Larocca A, Rossi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-weekly bortezomib in multiple myeloma patients. Blood. 2010. Dec 2;116(23):4745–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-294983. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moreau P, Pylypenko H, Grosicki S, et al. Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet Oncol. 2011. May;12(5):431–40. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70081-X. PubMed PMID: 21507715. **Clinical trial that established the safety and efficacy of subcutaneous bortezomib.

- 32.Reece DE, Sullivan D, Lonial S, et al. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of two doses of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011. Jan;67(1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1283-3. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3951913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreau P, Karamanesht II, Domnikova N, et al. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and covariate analysis of subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012. Dec;51(12):823–9. doi: 10.1007/s40262-012-0010-0. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pekol T, Daniels JS, Labutti J, et al. Human metabolism of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib: identification of circulating metabolites. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005. Jun;33(6):771–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002956. PubMed PMID: 15764713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uttamsingh V, Lu C, Miwa G, et al. Relative contributions of the five major human cytochromes P450, 1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4, to the hepatic metabolism of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005. Nov;33(11):1723–8. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005710. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labutti J, Parsons I, Huang R, et al. Oxidative deboronation of the peptide boronic acid proteasome inhibitor bortezomib: contributions from reactive oxygen species in this novel cytochrome P450 reaction. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006. Apr;19(4):539–46. doi: 10.1021/tx050313d. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leal TB, Remick SC, Takimoto CH, et al. Dose-escalating and pharmacological study of bortezomib in adult cancer patients with impaired renal function: a National Cancer Institute Organ Dysfunction Working Group Study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011. Dec;68(6):1439–47. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1637-5. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3481841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LoRusso PM, Venkatakrishnan K, Ramanathan RK, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of bortezomib in patients with advanced malignancies and varying degrees of liver dysfunction: phase I NCI Organ Dysfunction Working Group Study NCI-6432. Clin Cancer Res. 2012. May 15;18(10):2954–63. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2873. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3834726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aghajanian C, Soignet S, Dizon DS, et al. A phase I trial of the novel proteasome inhibitor PS341 in advanced solid tumor malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2002. Aug;8(8):2505–11. PubMed PMID: . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:2487–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. PubMed PMID: . Clinical trial that led to the first approval of bortezomib for relapsed myeloma.

- 41.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster M, et al. Extended follow-up of a phase 3 trial in relapsed multiple myeloma: final time-to-event results of the APEX trial. Blood. 2007. Nov 15;110(10):3557–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-036947. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Durie BG, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017. Feb 04;389(10068):519–527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31594-X. PubMed PMID: 28017406. **The first prospective randomised phase 3 trial of the three drug combination bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone versus the two drug combination lenalidomide and dexamethasone in NDMM without intent for immediate AHSCT

- 43.Mateos MV, Richardson PG, Schlag R, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone compared with melphalan and prednisone in previously untreated multiple myeloma: updated follow-up and impact of subsequent therapy in the phase III VISTA trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010. May 1;28(13):2259–66. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.0638. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cavo M, Tacchetti P, Patriarca F, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet. 2010. Dec 18;376(9758):2075–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61424-9. PubMed PMID: . **Study that established the VTD regimen as a standard induction therapy for transplant-eligible myeloma patients.

- 45.Sonneveld P, Schmidt-Wolf IG, van der Holt B, et al. Bortezomib induction and maintenance treatment in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: results of the randomized phase III HOVON-65/ GMMG-HD4 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012. Aug 20;30(24):2946–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6820. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J, Yang H, Liang X, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma with del(17p). Oncotarget. 2017. Sep 22;8(37):62435–62444. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18722. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5617517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sin N, Kim KB, Elofsson M, et al. Total synthesis of the potent proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin: a useful tool for understanding proteasome biology. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1999. Aug 2;9(15):2283–8. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuhn DJ, Chen Q, Voorhees PM, et al. Potent activity of carfilzomib, a novel, irreversible inhibitor of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, against preclinical models of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2007;110:3281–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-065888. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanada M, Sugawara K, Kaneta K, et al. Epoxomicin, a new antitumor agent of microbial origin. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1992. Nov;45(11):1746–52. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang J, Wang Z, Fang Y, et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, metabolism, distribution, and excretion of carfilzomib in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2011. Oct;39(10):1873–82. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.039164. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kortuem KM, Stewart AK. Carfilzomib. Blood. 2013;121:893–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-459883. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Connor OA, Stewart AK, Vallone M, et al. A phase 1 dose escalation study of the safety and pharmacokinetics of the novel proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib (PR-171) in patients with hematologic malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2009. Nov 15;15(22):7085–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0822. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4019989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Z, Yang J, Kirk C, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and drug-drug interaction of carfilzomib. Drug Metab Dispos. 2013. Jan;41(1):230–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.112.047662. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Badros AZ, Vij R, Martin T, et al. Carfilzomib in multiple myeloma patients with renal impairment: pharmacokinetics and safety. Leukemia. 2013. Aug;27(8):1707–14. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.29. PubMed PMID: 23364621; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3740399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steele JM. Carfilzomib: A new proteasome inhibitor for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2013. Dec;19(4):348–54. doi: 10.1177/1078155212470388. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Besse A, Stolze SC, Rasche L, et al. Carfilzomib resistance due to ABCB1/MDR1 overexpression is overcome by nelfinavir and lopinavir in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2018. Feb;32(2):391–401. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.212. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5808083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hawley TS, Riz I, Yang W, et al. Identification of an ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein)-positive carfilzomib-resistant myeloma subpopulation by the pluripotent stem cell fluorescent dye CDy1. Am J Hematol. 2013. Apr;88(4):265–72. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23387. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3608751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alsina M, Trudel S, Furman RR, et al. A phase I single-agent study of twice-weekly consecutive-day dosing of the proteasome inhibitor carfilzomib in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma or lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012. Sep 1;18(17):4830–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3007. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niesvizky R, Martin TG 3rd, Bensinger WI, et al. Phase Ib dose-escalation study (PX-171–006) of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and low-dose dexamethasone in relapsed or progressive multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013. Apr 15;19(8):2248–56. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3352. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4149337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shah JJ, Stadtmauer EA, Abonour R, et al. Carfilzomib, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory myeloma. Blood. 2015. Nov 12;126(20):2284–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-05-643320. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4643003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jakubowiak AJ, Dytfeld D, Griffith KA, et al. A phase 1/2 study of carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone as a frontline treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;120:1801–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-422683. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mikhael JR, Reeder CB, Libby EN, et al. Phase Ib/II trial of CYKLONE (cyclophosphamide, carfilzomib, thalidomide and dexamethasone) for newly diagnosed myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2015. Apr;169(2):219–27. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13296. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4521972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vij R, Wang M, Kaufman JL, et al. An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 (PX-171–004) study of single-agent carfilzomib in bortezomib-naive patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2012;119:5661–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-414359. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vij R, Siegel DS, Jagannath S, et al. An open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study of single-agent carfilzomib in patients with relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma who have been previously treated with bortezomib. Br J Haematol. 2012. Sep;158(6):739–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09232.x. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5818209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Stewart AK, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, et al. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015. Jan 8;372(2):142–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411321. PubMed PMID: 25482145. **Phase III trial that validated the regimen of carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory myeloma.

- 66.Siegel DS, Dimopoulos MA, Ludwig H, et al. Improvement in Overall Survival With Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2018. Mar 10;36(8):728–734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5032. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Berenson JR, Cartmell A, Bessudo A, et al. CHAMPION-1: a phase 1/2 study of once-weekly carfilzomib and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2016. Jun 30;127(26):3360–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-683854. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4929927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Moreau P, Mateos MV, Berenson JR, et al. Once weekly versus twice weekly carfilzomib dosing in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (A.R.R.O.W.): interim analysis results of a randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2018. Jul;19(7):953–964. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30354-1. PubMed PMID: . *A recent trial demonstrating the safety and eficacy of once-weekly carfilzomib dosing with dexamethasone.

- 69.Bringhen S, Mina R, Petrucci MT, et al. Once-weekly versus twice-weekly carfilzomib in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a pooled analysis of two phase 1/2 studies. Haematologica. 2019. Feb 7. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.208272. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Waxman AJ, Clasen S, Hwang WT, et al. Carfilzomib-Associated Cardiovascular Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2018. Mar 8;4(3):e174519. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4519. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5885859. *A review of carfilzomib-mediated cardiovascular adverse events, and potential causative/correlative associations.

- 71.Muz B, Ghazarian RN, Ou M, et al. Spotlight on ixazomib: potential in the treatment of multiple myeloma. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:217–26. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S93602. PubMed PMID: 26811670; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4714737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kupperman E, Lee EC, Cao Y, et al. Evaluation of the proteasome inhibitor MLN9708 in preclinical models of human cancer. Cancer research. 2010;70:1970–80. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2766. PubMed PMID: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.NINLARO® (ixazomib) capsules. For oral use. Full prescribing information. Cambridge (MA): Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; 2015. [cited cited 2007 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/208462lbl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 74.European Medicines Agency - Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Assessment Report. Ninlaro®[INN: ixazomib]. London: European Medicines Agency; 2016. [cited cited 2007 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/003844/WC500217623.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gupta N, Hanley MJ, Venkatakrishnan K, et al. The Effect of a High-Fat Meal on the Pharmacokinetics of Ixazomib, an Oral Proteasome Inhibitor, in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors or Lymphoma. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016. Oct;56(10):1288–95. doi: 10.1002/jcph.719. PubMed PMID: ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5069578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]