Summary

Background

Previously, we showed that the sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) transporter spinster 2 (Spns2) mediates activation of microglia in response to amyloid β peptide (Aβ). Here, we investigated if Ponesimod, a functional S1P receptor 1 (S1PR1) antagonist, prevents Aβ-induced activation of glial cells and Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology.

Methods

We used primary cultures of glial cells and the 5XFAD mouse model to determine the effect of Aβ and Ponesimod on glial activation, Aβ phagocytosis, cytokine levels and pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, AD pathology, and cognitive performance.

Findings

Aβ42 increased the levels of TLR4 and S1PR1, leading to their complex formation. Ponesimod prevented the increase in TLR4 and S1PR1 levels, as well as the formation of their complex. It also reduced the activation of the pro-inflammatory Stat1 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways, while activating the anti-inflammatory Stat6 pathway. This was consistent with increased phagocytosis of Aβ42 in primary cultured microglia. In 5XFAD mice, Ponesimod decreased the levels of TNF-α and CXCL10, which activate TLR4 and Stat1. It also increased the level of IL-33, an anti-inflammatory cytokine that promotes Aβ42 phagocytosis by microglia. As a result of these changes, Ponesimod decreased the number of Iba-1+ microglia and GFAP+ astrocytes, and the size and number of amyloid plaques, while improving spatial memory as measured in a Y-maze test.

Interpretation

Ponesimod targeting S1PR1 is a promising therapeutic approach to reprogram microglia, reduce neuroinflammation, and increase Aβ clearance in AD.

Funding

NIHR01AG064234, RF1AG078338, R21AG078601, VAI01BX003643.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Sphingosine-1-phosphate, Neuroinflammation, Ponesimod, Toll-like receptor 4, Phagocytosis

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

An estimated 6.2 million Americans aged 65 and older are living with Alzheimer's dementia. Current therapies are largely ineffective and only help manage symptoms in AD patients. In recent years, the FDA provided accelerated approval of antibodies against Aβ to slow the progression of AD. No medications are currently available for patients at the onset and middle stages of AD. Thus, there is a significant need to develop new treatment strategies. Ponesimod was reported to reduce neuroinflammation, however, it is unknown whether Ponesimod prevents neuroinflammation and AD pathology.

Added value of this study

We uncovered that Ponesimod reduces neuroinflammation by targeting S1PR1 to antagonize the pro-inflammatory MAPK/Stat1/3 signaling pathway. This results in the reduction of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and CXCL10, and the upregulation of the anti-inflammatory IL-33/Stat6 cell signaling pathway, which activates Aβ42 phagocytosis by microglia. In 5XFAD mice, Ponesimod leads to the reduction of AD pathology and improvement of spatial memory.

Implications of all the available evidence

There is currently no drug increasing Aβ clearance by glial cells. There is also no AD therapy targeting sphingolipid cell signaling pathways in AD pathogenesis. In the present study, we target sphingolipid cell signaling pathways to prevent neuroinflammatory activation of microglia and enhance glial clearance of Aβ. Therefore, our study elucidates a new mechanism for activation of Aβ clearance and potential AD therapy.

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a devastating neurodegenerative disease characterized by the accumulation of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles that are mainly composed of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide and microtubule-associated protein tau, respectively. The build-up of these neurotoxic proteins is critically regulated by the activation status of microglia and astrocytes, two cell types that mediate clearance of Aβ and tau. Particularly, microglia can adopt different activation states, which either promote Aβ phagocytosis and clearance or secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines that worsen AD. Studies in our lab and other groups have shown that the activation state of microglia is modulated by sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), a pro-inflammatory cell signaling sphingolipid, which affects Aβ phagocytosis by microglia.1,2 The molecular mechanisms underlying these S1P effects are not clear. It is also not clear how microglial activation by S1P-dependent cell signaling pathways can be targeted for AD therapy.

S1P is a pleiotropic bioactive lipid that regulates many pathophysiological processes including inflammation.3, 4, 5, 6 Extracellular S1P activates a family of G-protein coupled receptors termed S1P receptors (S1PRs), including those in astrocytes and microglia. Specifically, S1PR1 is critical for the induction of neuroinflammation in astrocytes and microglia.7,8 However, only little is known about the function of S1P/S1PR1 signaling in microglial amyloid clearance and AD pathogenesis. Targeting the S1P cell signaling pathway could be a promising strategy to prevent pro-inflammatory activation of microglia in AD. To date, FDA-approved drugs acting as S1PR antagonists are used in the therapy of relapsing multiple sclerosis (MS). The first of its kind drug was FTY720 (Fingolimod),9 a modified fungal metabolite and S1PR modulator. FTY720 induces endocytosis and proteolytic degradation of S1PR1, which prevents S1P-induced egress of lymphocytes from lymph nodes and migration of auto aggressive T-cell to the CNS.10 More recently, FTY720 was shown to have a direct CNS effect by preventing pro-inflammatory activation of astrocytes and microglia, which led to its application in animal models for AD.11,12 While it reduced pathophysiological hallmarks such as plaque formation and cognitive decline in the 3XTg, APP/PS1 and 5XFAD mouse models,13, 14, 15 the mechanism for its neuroprotective effect is not clear. The limitation of FTY720 is due to its lack of specificity by targeting several S1P receptors with partial agonist or antagonist function.16, 17, 18 In addition, it requires phosphorylation by sphingosine kinases to be become effective and shows several unwanted side effects in therapy.9,19, 20, 21

Ponesimod (ACT-128800 (Z,Z)-5-[3-chloro-4-(2R)-2,3-dihydroxy-propoxy)-benzylidene]-2-propylimino-3-o-tolylthiazolidin-4-one) was developed as a specific S1PR1 antagonist that does not require phosphorylation for its activity.19 The specificity of Ponesimod is 4.4-fold higher for targeting S1PR1 and 150-fold lower for activating S1PR3 as compared to S1P.22 Therefore, Ponesimod is a highly selective S1PR1 modulator.22,23 Ponesimod attenuates inflammation, demyelination and axonal loss in the brain and spinal cord of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), an animal model for MS.24 Recently, Ponesimod has been approved by the FDA for MS therapy.25 Tissue distribution studies show that Ponesimod can penetrate the blood–brain-barrier and partition to the brain and spinal cord.19,26 These studies indicate that, in addition to preventing access of lymphocytes to the CNS, Ponesimod may have also direct effects on neuroprotection and anti-neuroinflammation via downregulating S1PR1 cell signaling pathways in neural cells.

In this study, we investigated the role of S1PR1 and the effect of Ponesimod on Aβ-induced neuroinflammatory cell signaling pathways and AD pathology in vitro and in vivo. While activation of the signal transducer and transcription activator Stat1 and Stat3 pathways in microglia were identified as downstream targets of S1P and toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) in neuroinflammation, it is not known how this activation is coordinated by S1PR1 and TLR4.27, 28, 29 To test co-activation of S1PR1 and TLR4 as well as downregulation of neuroinflammation by Ponesimod, we used complementary in vitro and in vivo approaches. Using primary cell cultures of microglia and astrocytes, we determined the Aβ42-induced interaction of S1PR1 with TLR4 and the effect of Ponesimod on Stats cell signaling pathways, as well as its effect on microglial phagocytosis of Aβ42. In vivo, we treated 5XFAD mice with Ponesimod and measured glial activation, cytokine levels, amyloid plaque formation, and spatial memory function using a Y-maze behavioral test. In vitro, Ponesimod downregulates pro-inflammatory cell signaling pathways and promotes microglial phagocytosis of Aβ42. In vivo, Ponesimod reduces glial activation, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, AD pathology, and spatial memory impairment, indicating that it can be used for AD therapy.

Methods

Ethics statement

Animal experiments were performed in compliance with animal use guidelines and ethical approval, which was approved by the University of Kentucky's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (AUP #2017-2677).

Animals

Mice expressing five mutations in human APP and PS1 (5XFAD) (B6SJL-Tg [AβPP ∗K670N∗M671L∗I716V∗V717I, PSEN1∗M146∗L286V]6799Vas/J) under the Thy1 promoter were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Hemizygous 5XFAD mice were crossed with C57BL6/J mice to maintain the 5XFAD and non-transgenic wild type (WT) colonies. Animals were housed under a 12 h light/dark cycle in individually ventilated cages. Food and water were provided ad libitum throughout the study.

A total of thirty-two 5XFAD mice (equal numbers of male and female mice) at the age of 8.5-9-month old were randomly divided into two treatment groups, and 16 of mice were included in each group: vehicle-treated group (0.7% gelatin +5% DMSO, 50 μl/10g) and Ponesimod-treated (30 mg/kg) group. Based on the resource equation approach to calculate the sample size: E = (16 + 16)–2 = 30 > 10, we considered the sample size to be sufficient.30 Mice were orally gavaged with Ponesimod (Selleckchem, Houston, TX) or vehicle once a day for 4 weeks. After feeding, animals were transferred to the animal behavior core at the University of Kentucky for the Y-maze behavior test and then euthanized. Brains were extracted and the tissue further analyzed as described in Methods. All of the mice survived until the finalization of the drug administration. No criteria were set for including or excluding animals and there was no exclusion of mice in this study.

Human brain samples

Human brains were obtained from the UK-ADRC autopsy cohort, a community-based cohort actively recruiting from the Lexington, Kentucky region, which was described previously along with recruitment details.31 Briefly, older adult volunteers agreed to be followed for clinical examination and to donate his or her brain at the time of death. Protocols were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent. The age, sex and race information of AD patients and healthy controls are listed in the table.

| Healthy Control | AD patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Sex | Race | Age | Sex | Race |

| 91 | Female | White | 83 | Female | White |

| 83 | Female | White | 85 | Female | White |

| 86 | Female | White | 93 | Female | White |

| 94 | Male | White | 92 | Male | White |

| 81 | Male | White | 84 | Male | White |

Cell culture

Glial cells

Primary glial cells were isolated from the brains of P1–P3 (day at birth or next day) C57BL/6 wild-type mouse pups following our previously published protocol.32 The brain cortices were dissociated in ice-cold PBS, minced to the small pieces and digested with 0.25% Trypsin for 30 min at 37 °C. After digestion of brain tissues, the tissue suspension was passed through a 70 μm filter. Cell suspensions were centrifuged at 300×g for 5 min, and the harvested cell pellets were resuspended with DMEM (Corning, 10-015-CV, Glendale, Arizona) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA) 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin and plated into T-75 flasks (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Glial cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After 7–10 days, adherent cells were passed to 24-well plates containing uncoated glass coverslips and cultured in DMEM as described above. Prior to treatment, the cells were deprived of FBS overnight. Cells were fixed and then further analyzed by immunocytochemistry as described in Methods.

Microglia

Microglia were separated from the glial cells following previously published protocols.1 In detail, the mixed glia culture was maintained in 10% FBS for about 7–10 days. Then microglia were collected by gently shaking the flasks and plating detached cells on coverslips coated with Poly l-lysine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), thereafter microglia were maintained in 25% of the original glia culture medium and 75% of fresh DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (GIBCO, Cat# SV30010)/for another two days. Microglia were incubated with FBS-free medium overnight before 1 μM Aβ42-555 (Anaspec, Cat# AS-60480-01, Fremont, CA) with or without 10–100 nM Ponesimod treatment for 24 h. Then microglia on the coverslips were washed by 1XPBS 3 times and fixed for immunofluorescence labeling.

Adult microglia

Primary adult microglia were isolated and cultivated from adult 5XFAD mice at 6 months old of age using the MACS® Tissue Dissociation Kit from Miltenyi Biotec in 24 well plates with coverslips coated with Poly-l-lysine. Microglia were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS for 5 days. Thereafter, cells were deprived of serum overnight. The second day, microglia were incubated with 1 μM Aβ42-555 (Anaspec, Cat# AS-60480-01, Fremont, CA) with or without 100 nM of Ponesimod for 24 h.

BV2 cells

BV2 cells were a kind gift from Dr. Guanghu Wang, Department of Physiology, University of Kentucky. Cells were maintained in DMEM/F12 (1:1) (Gibco, #11320-033) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS and 1% of penicillin-streptomycin. BV2 cells were incubated with FBS-free DMEM/F12 (1:1) medium overnight before 1 μM Aβ42-555 (Anaspec, Cat# AS-60480-01, Fremont, CA) with or without 10–100 nM Ponesimod treatment for 24 h. Then BV2 cells were harvested for flow cytometric analysis of phagocytic Aβ42-555. The short tandem repeat (STR) analysis of BV2 cells was performed by Labcorp (Burlington, NC). Absence of mycoplasma infection was confirmed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining in the laboratory.

Hela cells

The Hela cell line was from ATCC (ATCC-CCL-2). Cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cell lines were authenticated by ATCC by STR analysis and free of mycoplasma.

Immunofluorescence labeling

Cells or brain sections were fixed with 4% p-formaldehyde/0.5% glutaraldehyde/PBS for 15 min and then permeabilized by incubation with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 3% ovalbumin in PBS solution for 1 h at 37 °C. Then the coverslips with cells or slides with brain sections were incubated with primary antibodies in PBS with 0.5% ovalbumin (CD68, rat Abcam, Cat#ab125212, 1:300; Iba-1, goat Novus, Cat# NB100-1028, 1:500; GFAP, rabbit Dako, Cat#Z033429-2, 1:500; iNOS, mouse Novus, Cat#610328, 1:200; Aβ42, mouse Biolegend, Cat#800701, Clone 4G8, 1:200; Aβ, rabbit HL31L21, Thermo Fisher Cat#700254, 1:400) overnight at 4 °C. The next day, after washing with PBS, the coverslips or slides were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 647 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Goat IgG (H + L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat#705-605-147, 1:250) or Alexa Fluor® 488 AffiniPure F(ab')₂ Fragment Donkey Anti-Rat IgG (H + L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat#712-546-150, 1:250) and, after washing with PBS, embedded using Fluoroshield supplemented with DAPI (Sigma–Aldrich, Cat#F6057) to visualize the nuclei. If Fluoro-jade staining was performed, mouse brain sections were first incubated with 0.0001% Fluro-jade (Cat#AG325, Millipore) prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol for 45 min at room temperature and then rinsed with PBS prior to embedding. Immunofluorescence deconvolution microscopy was performed using a Nikon Ti2 Eclipse microscope equipped with NIS Elements software. Images were processed using a 3D deconvolution program as provided by the Elements software. Images (blinded identifiers) were randomly chosen and colocalization analyzed using the respective program in the NIS Elements software. The degree of colocalization was assessed by calculation of the Pearson's correlation coefficient for two fluorescence channels in overlays as previously described.33 PLA signals were also counted using the NIS Elements software. All of the data were collected from at least three independent experiments using at least five randomly selected areas/culture or slice.

Proximity ligation assay

Glia or microglia were grown on glass coverslips. After treatment, cells were fixed with 4% p-formaldehyde/0.5% glutaraldehyde/PBS for 15 min at 37 °C, and thereafter, cells were permeabilized by incubation with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with Duolink PLA blocking solution (Sigma–Aldrich) for 1 h at 37 °C. The primary antibodies used were: anti-TLR4 rabbit IgG (1:100, Abcam, Cat#ab13556), anti-S1PR1 mouse IgG (1:100, Santa Cruz, Cat# SC-48356), and anti-CD68 Rat IgG (1:100, Abcam, Cat#ab125212). Secondary PLA probes, anti-rabbit PLUS affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H + L), anti-goat MINUS affinity-purified donkey anti-goat IgG (H + L), and anti-mouse MINUS affinity-purified donkey anti-mouse IgG (H + L), were diluted 1:5 in 1 × antibody diluent buffer and samples incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing, ligation and amplification steps were performed following the manufacturer's protocol (Duolink, Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Coverslips were mounted using Fluoroshield supplemented with DAPI to visualize the nuclei. Fluorescence analysis was performed with a Nikon Ti2 Eclipse microscope equipped with NIS Elements software. Images were processed using a 3D deconvolution program as provided by the Elements software. Images obtained with secondary antibody only were used as negative controls representing the background intensity in a channel. Two channels (DAPI and TRITC) were separated to analyze nuclear staining (DAPI) of the images separately from the TRITC-channel associated with the PLA dots. Firstly, a threshold was set in order to identify nucleus and to allow for binary conversion (black and white). A morphological function was used to separate touching nuclei. Nuclei were counted and added to the region of interest (ROI) where the appropriate minimum and maximum pixel area sizes were set. In the other channel, the number of dots (PLA signals) in each cell as identified by labeling of nuclei was calculated with the “Measure” command from the ROI manager using single point as an output type.

Immunoblot analysis

For Western blot analysis, protein from frozen brain tissue or cell pellets was solubilized with 2X Laemmli sample buffer (Sigma–Aldrich, Cat#S3401). The protein concentration was determined using the RC DC™ protein assay (Biorad, Cat#500-0119). The protein samples were resolved by SDS gel electrophoresis on polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond ECL, Amersham Biosciences, UK). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% fat-free dry milk in TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies. The membranes were then incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-phospho-ERK (Cell signaling, Cat#9101S)/phospho-p38 (Cell signaling, Cat#9215S)/phospho-JNK (Cell signaling, Cat# 9255S), anti-phospho STAT1 (Cell signaling, Cat# 9167S)/anti-phospho STAT3 (Cell signaling, Cat#9145S) anti-phospho STAT6 (Cell signaling, Cat# 56554), anti-GAPDH (Cell signaling, Cat#5174) or β-Actin (Santa Cruz, sc-47778), which were used as a control. The membranes were rinsed three times with TBST and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated) for 1 h at 25 °C. The immunoblots were developed with western blotting detection ECL reagents (Thermo Fisher, Cat#34580, USA) and images were taken via Azure Biosystems (VWR). The quantification of protein band intensities was carried out using image J software, and the optical density of each sample was corrected using the optical density of the corresponding β-actin or GAPDH.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Hela cells were seeded on the 60 mm dishes until reaching 70–80% confluence. Cells were incubated with FBS-free DMEM overnight. Cells were then transfected with TLR4-YFP (a gift from Dr. Doug Golenbock, Addgene plasmid #13018) and Flag-S1PR1 (a gift from Dr. Bryan Roth, Addgene plasmid # 66496) for about 60 h. Next, the cell culture media were removed and cells were washed with FBS-free DMEM once. The transfected cells were treated with 1 μM Aβ42 and/or 100 nM of Ponesimod for 4 h. The cell pellets were harvested and transferred into a Dounce homogenizer and sonicated in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat#A32961). Insoluble debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,800×g for 30 min at 4 °C and Triton X-100 was added to the supernatant at a final concentration of 0.25%. The protein concentrations in the supernatants from each treatment were adjusted to the same concentration and the same volume. Lysates were pre-cleared with 20 μL of Pierce protein A/G magnetic beads (Pierce Biotechnology, Cat#88802, Rockford, USA) for 1 h at 4 °C under rotational movement and then incubated overnight with mouse TLR4 antibody (Novus, Cat#NB100-56566) at 4 °C under rotational movement. Then, 20 μL of Pierce protein A/G magnetic beads were added to the samples and incubated overnight at 4 °C under rotational movement. The beads were harvested and washed three times by washing buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5, supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors/0.25% Triton X-100. Protein bound to the beads was eluted by SDS-sample buffer containing 10% 2-mercaptoethanol for 30 min at 60 °C and then subjected to SDS-PAGE for immunoblotting using anti-S1PR1 rabbit IgG (Abcam, Cat# ab77076).

Labeling of amyloid plaques, reactive microglia and astrocytes in brain sections

For immunohistochemistry, brain cryosections were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 3% ovalbumin in PBS solution for 1 h at 37 °C. For labeling reactive astrocytes, microglia and amyloid plaques, brain sections were immunolabeled with primary antibodies anti-GFAP rabbit IgG (Dako, Cat#Z033429-2, 1:500), anti-Iba-1 goat IgG (Novus, Cat#NB100-1028, 1:500), anti-Aβ42, Biolegend, Clone 6E10, Cat#803001, 1:500 or Cat#800701, Clone 4G8, 1:200) and after washing with PBS, Alexa 488 donkey anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat#715-546-150, 1:250). Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-goat (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat#705-166-147, 1:250) and Alexa 647 donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cat#711-606-152, 1:250). Slices were embedded with Fluoroshield containing DAPI. Fluorescence analysis was performed with a Nikon Ti2 Eclipse microscope equipped with NIS Elements software as described.

Behavioral tests

The Y-maze spontaneous alternation (AYM) test was done to assess spatial working memory, which were conducted in Rodent Behavioral Core (RBC) at the University of Kentucky. The Y-maze apparatus have Y-shaped maze with three opaque arms spaced 120° apart. For three arms, two of them are 15.24 × 7.62 × 12.7 cm, one is 20.32 × 7.62 × 12.7 cm. No visual or auditory cues were present in any of the arms. The overhead camera was mounted to the ceiling directly above the apparatus for real-time monitoring of the mouse movements. Standing lamps with four of white light bulbs were placed at corners outside privacy blinds pointed away from the apparatus. Light meter was used to measure illumination in arms of apparatus. Clidox was used between trials to eliminate visual and olfactory residue in the arena.

Before testing, mice in home cage were placed in the testing room for at least 1 h before testing to minimize effects of stress on behavior during testing. Then the mouse was placed just inside arm A facing away from the center and allowed to move through the apparatus for 5 min while being monitored by the automated tracking system. The trial began immediately and ended when defined duration had elapsed. The scoring consisted of recording each arm entry (defined as all four paws entering arm). Scorings were conducted live if possible by monitoring movement through the apparatus via a computer screen. If an animal consecutively entered three different arms, it was counted as a spontaneous alternation performance (SAP), which is an indication of sound working memory. If an animal went from A to B and came back to A, it was counted as an alternate arm return (AAR). Any time a mouse went from an arm (e.g., arm A) to the center and came back to the same arm (A), it was counted as a same arm return (SAR). The total number of entries did not include the first recorded arm (always B). The score of alternation was calculated using the formula: Number of triads = (Total entries − 2). Triad (set of three letters) containing all three letters was scored as alternation. Percent alternation = [(# of Alternations/Total # of triads) ∗100].

After completion of the Y-maze behavioral test, the mice were sacrificed by decapitation. Brains were quickly removed and hemisected on ice; Half brains were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for future biochemical analysis. Another half of brain was fixed in 4% of PFA solution for preparation of cryosections and immunocytochemistry analysis.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as mean ± SEM and analyzed with GraphPad Prism 9 software. Differences between each group were analyzed by one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA followed by Turkey's multiple comparisons test or Student's t-test comparisons. P-values below 0.05 were considered as significant. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

Role of funders

The funding agencies had no contributions in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, and writing of report.

Results

TLR4 and S1PR1 levels are increased in AD brain and in vitro by Aβ42, which is prevented by ponesimod treatment

Previously, it has been shown that TLR4 is upregulated in AD and mediates activation of astrocytes and microglia.34,35 It is also known that S1PR1 is involved in activation of astrocytes and microglia, however, the quantitation of S1PR1 in AD and its interaction with TLR4 has not been reported yet. To test if TLR4 and S1PR1 are co-regulated, we determined the protein levels of the two receptors in brain tissue of 5XFAD mice and AD patient brain. Fig. 1A and B shows that the levels of S1PR1 and TLR4 were increased by 2-fold and 1.5-fold in 5XFAD mouse brain, and 1.5-fold and 3-fold in the grey matter of AD patients’ brain, respectively. We did not observe the similar changes in the white matter of human brain (Supplemental Fig. S1A), suggesting that the observed changes did not involve oligodendrocytes. To understand the role of TLR4 and S1PR1 and their interaction in AD, 1 μM of oligomeric Aβ42 was applied to primarily cultured glia. Immunoblot analyses showed that Aβ42 increased the levels of TLR4 and S1PR1 by 3-fold and 1.2-fold, respectively, which was blocked by treatment with Ponesimod (Fig. 1C and D). In summary, our data demonstrated that in AD brain as well as Aβ42-exposed glia, TLR4 and S1PR1 are simultaneously elevated, suggesting that Aβ42 induces upregulation of the two receptor proteins as part of a glial activation process in AD.

Fig. 1.

Ponesimod prevents Aβ-induced increase of TLR4 and S1PR1 levels. A. Levels of TLR4 and S1PR1 in 5XFAD (N = 3 controls and 3 5XFAD mice, T-test). P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. B. Levels of TLR4 and S1PR1 in AD patient brain grey matter (N = 5 healthy and 5 AD brains, T-test). Bar graphs show means ± SEM. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. C, D. Primary cultures of mixed glia were treated with 1 μM Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 10 nM (in C) or 100 nM Ponesimod (Pone, in C and D) for 24 h. Levels of TLR4 and S1PR1 were determined using immunoblotting. N = 3. One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey's multiple comparisons test.

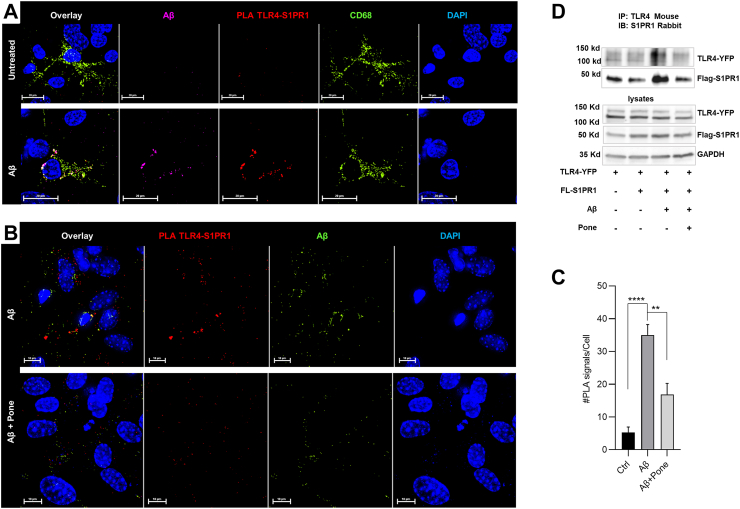

Aβ42 induces formation of a complex between TLR4 and S1PR1, which is phagocytosed and degraded after treatment with ponesimod

To test if the Aβ42-induced increase of the TLR4 and S1PR1 levels involves the molecular interaction of these two receptor proteins, we incubated a primary glial culture with HiLyteTM Fluor 555-labeled Aβ42 and performed proximity ligation assays (PLAs) using antibodies against TLR4 and S1PR1. Fig. 2A and B shows that Aβ42 induced TLR4-S1PR1 complex formation in microglia as confirmed by quantitation of PLA signals in CD68 (+) microglia (Fig. 2C). Since CD68 is also a phagosome marker, colocalization with the PLA signals suggested that the Aβ42-induced TLR4-S1PR1 complex was internalized by phagocytosis. To confirm Aβ42-induced complex formation, we transfected Hela cells with YFP-tagged TLR4 and Flag-tagged S1PR1 and performed co-immunoprecipitation assays. Fig. 2D shows that overexpression of the two proteins did not enhance complex formation (lanes 1 and 2), while incubation with Aβ42 (lane 3) increased the amount of Flag-S1PR1 co-immunoprecipitated with antibody against TLR4. Strikingly, incubation with Ponesimod (lane 4) greatly reduced the amount of co-immunoprecipitated Flag-S1PR1 in Aβ42-treated cells. This was consistent with the decrease of the number of TLR4-S1PR1 PLA signals under Ponesimod treatment (Fig. 2B). Therefore, our data suggested that Aβ42-induced complex formation was either prevented by Ponesimod or the receptor protein(s) degraded. Taken into consideration that the protein level of TLR4 as well as S1PR1 was decreased by Ponesimod in Aβ42-treated glial culture (Fig. 1C and D), we concluded that the TLR4-S1PR1 complex was phagocytosed and then degraded.

Fig. 2.

Aβ42induces a complex between TLR4 and S1PR1. A, B. Primary cultures of mixed glia cells were treated with 1 μM Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 100 nM Ponesimod (Pone) for 24 h. Proximity ligation assays (PLAs) were performed using anti-TLR4 and S1PR1 antibodies (PLA, red) and co-labeled for Aβ42 (purple in A or green in B) and phagosomes (CD68+, green) visualized with the respective antibodies. The quantitation of PLA signals is shown in C. Data shows means ± SEM. N = 3, One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey's multiple comparisons test, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. D. Hela cells were transfected with TLR4-YFP and Flag-S1PR1 and then treated with 1 μM Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 100 nM Ponesimod (Pone) for 4 h. Cell lysates were incubated with 1 μg of TLR4 mouse antibody to co-immunoprecipitate S1PR1. Captured protein was analyzed by SDS-immunoblotting with anti-S1PR1 rabbit antibody. N = 3.

Ponesimod enhances phagocytosis of Aβ42 in primary cultured glia

The observation that Ponesimod enhanced degradation of TLR4 and S1PR1, potentially after phagocytosis of the Aβ42-induced complex of the two receptor proteins in microglia, prompted us to investigate if Ponesimod also enhanced microglial phagocytosis and degradation of Aβ42. To test this, we treated primary microglia with HiLyte™ Fluor 555-labeled Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 100 nM of Ponesimod for 24 h. Microglia were then immunolabeled for Iba-1 and phagosomes for CD68. Fig. 3A, C, and Supplemental Fig. S1D show that Ponesimod increased the amount of fluorescently labeled Aβ42 inside of primary cultured microglia prepared from brain tissue of pups and 6-month-old 5XFAD mice. A proportion of Aβ42 was colocalized with CD68, indicating that microglia phagocytosed Aβ. To quantify the Ponesimod-induced phagocytosis of Aβ42 into microglia, we treated BV2 cells with HiLyte™ Fluor 555-labeled Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 10 nM and 100 nM of Ponesimod for 24 h and quantified fluorescence using flow cytometry. Fig. 3B shows that the HiLyte™ Fluor 555 mean fluorescence density (GEO mean value) in BV2 cells was increased by 10 nM Ponesimod, while 100 nM did not increase fluorescence significantly. These data suggested that Aβ42 phagocytosis is enhanced at a lower concentration of Ponesimod, which could be followed by proteolytic degradation of Aβ42 at a higher Ponesimod concentration. To further investigate the effect of Ponesimod, we incubated mixed glia with HiLyte™ Fluor 555-labeled Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 10 nM of Ponesimod and quantified the colocalization with CD68 using immunofluorescence microscopy. In addition, we compared the effect of Ponesimod on phagocytosis with that of 200 nM FTY720, another functional antagonist of S1PR1, although less specific than Ponesimod. Fig. 3C and D shows that Ponesimod increased the Pearson's coefficient for the colocalization of Aβ42 and CD68 in microglia by about 2-fold, which was not observed when the culture was incubated with FTY720. These data suggested that in contrast to FTY720, Ponesimod enhanced phagocytosis of Aβ42 in microglia.

Fig. 3.

Ponesimod enhances phagocytosis of Aβ42. A. Primary cultures of microglia were treated with 1 μM HiLyte™ Fluor 555-labeled Aβ42 (red) in the presence or absence of 100 nM Ponesimod (Pone) for 24 h. Microglia were fixed and immunolabeled for Iba-1 (purple) and CD-68 (green). Bottom panel shows higher magnification of framed area in top panel. B. BV2 cells were treated with 1 μM HiLyte™ Fluor 555-labeled Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 10 nM or 100 nM Ponesimod (Pone) for 24 h and Aβ42 uptake quantified by flow cytometry. Bar graphs show means ± SEM. N = 3. ∗P < 0.05. C, D. Experiment performed as in A, however, with primary cultures of mixed glia. 200 nM FTY720 (F) was used for comparison with Ponesimod (P). The colocalization of Aβ42 and CD68 in Iba-1(+) cells was quantified using the Pearson's correlation coefficient as shown in (D). N = 3. One-way ANOVA followed by Turkey's multiple comparisons test, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

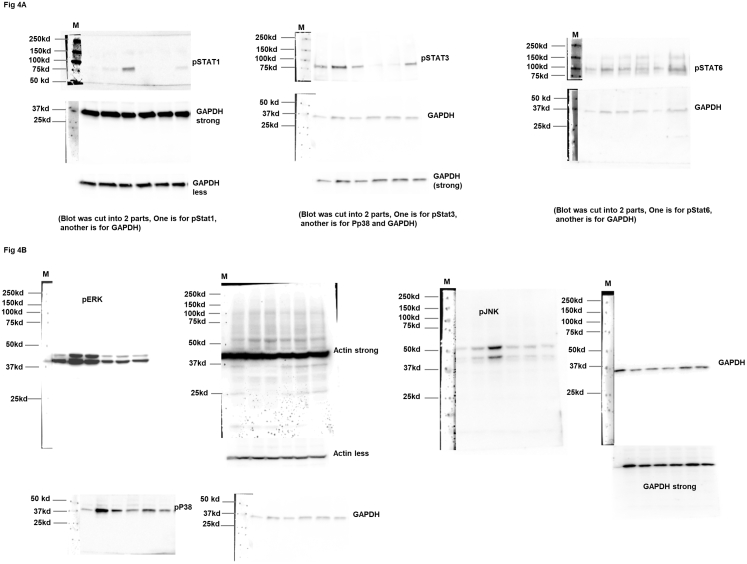

Ponesimod downregulates pro-inflammatory signaling in vitro

Increase of Aβ phagocytosis is characteristic for microglia and astrocytes with reduced activation of pro-inflammatory cell signaling pathways. To test if Ponesimod downregulated pro-inflammatory cell signaling pathways, we incubated primary cultured glia with Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 10 nM Ponesimod and quantified the level of activated (phosphorylated) Stat 1, 3, and 6 by immunoblotting. Phosphorylation of different Stats is known to be downstream of TLR4 and S1PR1 and one of the major cell signaling pathways for pro-inflammatory activation of microglia and astrocytes.7,36, 37, 38 Stat1 showed robust activation by Aβ42 (Fig. 4A), which was prevented by Ponesimod, consistent with the role of Stat1 in pro-inflammatory activation of microglia and astrocytes.38,39 In contrast to Stat1, Stat6 phosphorylation was increased by Ponesimod, consistent with its function in upregulation of Aβ phagocytosis.40,41 Stat3 was not consistently affected by Ponesimod in mixed culture, which may in part be due to the distinct functions of these Stats in microglia and astrocytes. In agreement with Stat1 activation by Aβ42 and downregulation by Ponesimod, downstream phosphorylation of ERK (p42-MAPK) was increased by Aβ42, which was prevented by Ponesimod. In addition to ERK, phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, a key regulator for the Aβ42 and TLR4 induced pro-inflammatory activation of microglia downstream of Stat1,42 was robustly increased by Aβ42, which was prevented by Ponesimod. JNK, another kinase activated in AD,43, 44, 45 was less affected by Ponesimod (Fig. 4B). In summary, our data showed that Aβ42 activated pro-inflammatory cell signaling pathways in mixed glial culture, particularly downstream of Stat1, which was prevented or reduced by Ponesimod.

Fig. 4.

Ponesimod downregulates neuroinflammatory cell signaling pathways in vitro. A, B. Primary culture of mixed glia were treated with 1 μM Aβ42 in the presence or absence of 10 nM Ponesimod (Pone) for 30 min and 4 h, then protein analyzed by immunoblotting. The phosphorylation of Stat1, Stat3, Stat6 and quantitation are shown in (A). The phosphorylation of ERK, p38 and JNK and quantitation are shown in (B). All data normalized to GAPDH or Actin. Bar graphs show means ± SEM. N = 4. T-test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

Ponesimod attenuates neuroinflammation in 5XFAD mice

To test the effect of Ponesimod on neuroinflammation in vivo, 8.5-9-month old male and female mice (5XFAD) were administered daily with vehicle or 30 mg/kg Ponesimod via oral gavage for 4 weeks. We then extracted the mouse brain cortices and analyzed the protein levels of TLR4 and S1PR1 and downstream signaling (pERK, p38, JNK) as well as a panel of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Fig. 5A shows that TLR4 was significantly reduced by Ponesimod treatment. In contrast to the results of our in vitro experiments, S1PR1 appeared not to be reduced by Ponesimod, which may be due to the complexity of cellular interaction in vivo. The level of phosphorylation of p38 MAPK was reduced by 30%, consistent with the effect of Ponesimod in vitro (Fig. 5B). The in vitro effect of Ponesimod on p42 MAPK (pERK) was not observable in vivo, which may not be surprising since p42 MAPK phosphorylation is known to be transient, while p38 MAPK is robustly activated in pro-inflammatory microglia.42 Likewise, we did not find a significant effect of long-term Ponesimod treatment on pJNK in vivo (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Ponesimod decreases neuroinflammatory cytokine levels and increases IL-33 in 5XFAD mice. A, B. Immunoblot analysis of protein from cortical brain tissue of 5XFAD mice with or without Ponesimod treatment. Right panels show quantitation after normalization to GAPDH. Bar graphs show means ± SEM. N = 8 in A (blots showing the other 3 pairs in Supplemental Fig. S1C) and N = 5 in B, T-test. ∗P < 0.05. C. U-plex assay shows the absolute concentration (pg/mg) of CXCL10, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-33 in mouse brain lysates. Bar graphs show means ± SEM. N = 4. T-test. ∗P < 0.05.

A U-PLEX analysis of lysates from mouse brain cortex showed that the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α (see also immunoblot in Supplemental Fig. S1B) and chemokine CXCL10 in 5XFAD cortex were decreased by Ponesimod treatment, consistent with reduced activation of their downstream effector p38 MAPK (Fig. 5C). In addition to reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, the level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-33 was increased by Ponesimod, which was confirmed by immunoblot analysis as shown in Supplemental Fig. S1B. Since CXCL10 and TNF-α trigger Stat1 and IL-33 upregulates Stat6, the U-PLEX data are consistent with the in vitro data on the effect of Ponesimod on Aβ-induced pro-inflammatory activation of microglia. In summary, our data on TNF-α, CXCL10, and IL-33 demonstrated that Ponesimod reduced neuroinflammation in vivo.

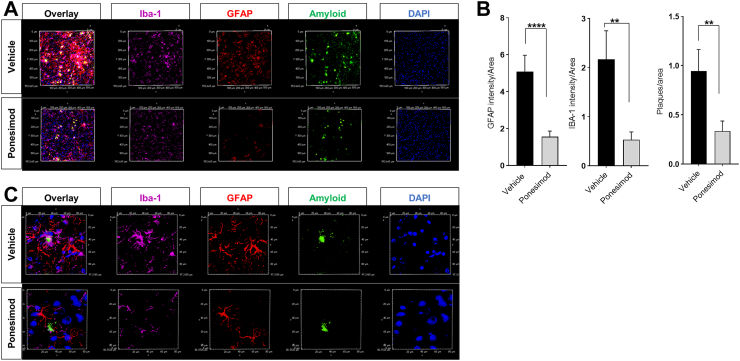

Ponesimod ameliorates AD pathology and cognition in the late stage of 5XFAD mice

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of AD pathology and associated with glial activation, accumulation of neurotoxic peptides and proteins such as Aβ and tau as well as cognitive decline. Using immunolabeling of markers for astrocyte (GFAP) and microglia (Iba-1) activation in cryosections of vehicle and Ponesimod-treated mice, we found that Ponesimod significantly decreased the number of GFAP (+) astrocytes and Iba-1 (+) microglia, indicating a reduction of glial activation (Fig. 6A and B, and Supplemental Fig. S4A and B). In addition, we found that Ponesimod reduced the number of iNOS (+) microglia, indicating that they are less inflammatory and detrimental to neurons (Supplemental Fig. S2A). This data was consistent with reduced Fluoro-jade staining of degenerating neurons in Ponesimod-treated mice, particularly in neurons not directly associated with amyloid plaques (Supplemental Fig. S3A–C). The reduction of Iba-1(+)/iNOS(+) microglia (Supplemental Fig. S2A) and Fluoro-jade (+) neurons (Supplemental Fig. S3B and C) was concurrent with a decrease in amyloid plaque number and area (Fig. 6A and B and Supplemental Fig. S3A), suggesting that clearance of amyloid plaques was increased.

Fig. 6.

Ponesimod ameliorates AD pathology in 5XFAD mice. A. Immunolabeling of Aβ42 (green) and activated astrocytes (GFAP, red) and microglia (Iba-1, purple) using cryosections from the brains of 5XFAD mice with or without Ponesimod (Pone) treatment. B. Quantitation of A. Bars show means ± SEM. T-test. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. C. Images of higher magnification and resolution.

To determine if Ponesimod improved cognition in late stage 5XFAD mice, we used the Y-maze alternation test on vehicle- and Ponesimod treated 8.5-9-month old male and female 5XFAD mice as compared to C57Bl/6 wild type (WT) control mice. The Y-maze test is a measure of the spontaneous tendency of the mice to alternate their free choices to enter the two arms of the maze (Fig. 7A). When the arm chosen for the first entry was registered, the wild type mice preferred the previously “unvisited” arm of the maze as the first choice and entered it more frequently (Fig. 7B). In contrast, vehicle-treated 5XFAD mice exhibited a reduced preference for the unvisited arm with fewer alternations (Fig. 7B and C, red bars). Ponesimod-treated 5XFAD mice showed a trend to an elevated number of the alternations for the unvisited arms as compared to the vehicle-treated 5XFAD mice (Fig. 7C, P = 0.0649). Importantly, vehicle-treated 5XFAD mice showed a significant increase of same arm returns (SAR) (Fig. 7D, P < 0.001, red bar), while Ponesimod-treated mice showed a significantly reduced preference of the SAR, indicating that Ponesimod improves spatial working memory in 5XFAD mice. In addition, Ponesimod-treated mice showed a higher number of alternate arm returns (AAR) as compared with the vehicle treated mice (Fig. 7E). Even though, the increase of AAR did not reach statistical significance, this result was consistent with the SAR data indicating that Ponesimod rescues attention/working memory in 5XFAD mice. Moreover, the total entries to both arms performed by vehicle- and Ponesimod-treated 5XFAD mice showed no differences (Fig. 7F), suggesting that either Ponesimod or vehicle treatment does not cause the anxiety-like behavior in 5XFAD mice. These Y-maze data suggests that Ponesimod improves spatial working memory in 5XFAD mice with advanced AD pathology.

Fig. 7.

Ponesimod improves spatial learning and memory in 5XFAD mice. The 8.5–9 month-old 5XFAD mice were gavaged with vehicle or Ponesimod continuously for four weeks. After completion of treatment, the mice were subjected to a Y-maze test to determine short-term spatial working memory. (A). Schematic of animal treatment, behavioral test and brain tissue collection (top), and the Y-maze (bottom). (B). Spontaneous alternation performance (SAP). Number shows percentage of trials for a mouse visiting 3 different arms in a triad entry. The number of alternations in vehicle-treated- and Ponesimod-treated- 5XFAD mice is shown in (C). (D). Same arm return (SAR) as the percentage of a mouse returning to the same arm in any consecutive entries in a triad entry. (E). Alternative arms return (AAR) as the percentage of a mouse going into alternative arms in a triad entry. (F). Total entries. There are no differences among each group of mice in the total number of entries. All of the statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA tests followed by Turkey's multiple comparisons test, except in (B), which was analyzed with One-sample t-test. (∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗P < 0.05, WT: N = 7, Vehicle: N = 16. Ponesimod: N = 16).

Discussion

Neuroinflammation is a hallmark of AD, one of the major causes for disease progression, and a promising drug target for AD therapy. Among the cell signaling pathways inducing neuroinflammation, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and its cognate S1P receptors (S1PRs) are sphingolipid-mediated cell signaling pathways currently explored as a drug target in AD therapy. Of the five S1P receptors known to be activated by S1P, S1P receptor 1, 2, 3, and 5 (S1PR1, 2, 3, 5) have been found to regulate activation and function of astrocytes and microglia in neuroinflammation.46 It is not clear which specific functions in glial activation are mediated by distinct S1P receptors and some of the S1P regulated pathways may counteract each other. The widely used FTY720 is an S1P pro-drug analog, which is phosphorylated by sphingosine kinases. Phospho-FTY720 targets S1PR1, 3, 4, and 5 and activates some, while inducing proteolytic degradation of other S1P receptors.47 Hence, drugs are needed that specifically antagonize individual S1P receptors that induce pro-inflammatory activation of astrocytes and microglia, while beneficial functions of activated glia such as Aβ clearance are not affected or even enhanced. We and others showed that S1PR1 is critical in inducing pro-inflammatory activation of astrocytes and microglia,2,7,8,48 while its role in Aβ phagocytosis and clearance has not been investigated yet. The goal of our study was to test if by specifically targeting S1PR1, Aβ phagocytosis can be maintained or induced while at the same time, preventing cytokine production and neuroinflammation aggravating AD pathogenesis.

To understand the functional role and interaction of S1PR1 and TLR4 in AD pathology, we evaluated the levels of S1PR1 and TLR4, which were increased in AD patient brain, 5XFAD mouse brain and Aβ42-treated glial cells when compared to the controls (Fig. 1). Our data were consistent with previous studies reporting the upregulation of TLR4 in APP/PS1 AD mice and in glial cells surrounding plaques in postmortem brains of AD patients.49 Recently, S1PR1 protein levels were shown to be upregulated in 8- and 14-month-old 5XFAD brain cortex, which is consistent with the results in our study.50 While Aβ42 was shown to directly affect or even bind to TLR4, it was not clear how Aβ42 increased the level of S1PR1. While Ponesimod is a highly specific functional antagonist of S1PR1, it was not clear how Ponesimod prevented the Aβ42-induced increase of TLR4. Based on a previous study showing that S1PR1 physically interacted with TLR4 in lung epithelial cells,51 we tested if Aβ induced a complex of S1PR1 with TLR4 in primary cultured glia and how Ponesimod affected this complex formation. Our data from PLAs and co-immunoprecipitation assays showed that Aβ42 induced an S1PR1-TLR4 complex, which was internalized and then probably degraded by simultaneous incubation with Ponesimod. While our current study focuses on the Aβ42-induced interaction of S1PR1 and TLR4, it should be noted that TLR2 has also been shown to be activated by Aβ and induce microglial neurotoxicity.52 We will investigate a potential interaction of S1PR1 and TLR2 as well as the effect of Ponesimod on this interaction in future studies. Moreover, our study did not investigate the effect of S1P or the mechanism of S1PR1 and TLR4 uptake and degradation, which will be tested in future experiments as well. However, we compared the effect of Ponesimod on Aβ42 uptake with that of FTY720. Our data showed that Ponesimod increased uptake of Aβ42 in primary cultured microglia in the brain from younger pups and microglia from 6-month old 5XFAD mouse brain (Fig. 3A, and Supplemental Fig. S1D), while FTY720 had no effect on Aβ42 uptake. A recent study showed that the beneficial effect of FTY720 on AD pathology was limited to male mice, a limitation we did not observe with Ponesimod.53 The authors suggested that FTY720 mainly affects the neuroinflammatory reaction to ongoing Aβ deposition. Therefore, we conclude that the activity of FTY720 is distinct from that of Ponesimod, which stimulates phagocytosis and therefore, preserves the neuroprotective function of activated microglia in AD, even after deposition of amyloid plaques.

Neuroprotection by microglia in AD is mainly compromised by switching activation of microglia from a phagocytotic to a neuroinflammatory phenotype. Induction of neuroinflammation in microglia is depending on a self-amplifying cascade of cell signaling pathways induced by Aβ and cytokines, several of them being downstream of TLR4 and implicated in the regulation of phagocytosis and Aβ clearance.54, 55, 56, 57 It is currently debated how Aβ affects TLR4 activation for the regulation of phagocytosis, which is likely to depend on co-regulators or modifiers such as S1P as proposed in the current study. Specifically, we found that Ponesimod prevented Aβ42-induced phosphorylation activation of Stat1, while leading to increased phosphorylation of Stat6. Activation of Stat1 is characteristic for pro-inflammatory microglia with decreased phagocytosis and reduced clearance of Aβ.39,58 Decrease of Stat1 activation by Ponesimod is consistent with lower activation of p42 and p38 MAPK, two protein kinases activated in pro-inflammatory microglia and AD brain.59, 60, 61 Therefore, Ponesimod-induced inhibition or downregulation of the canonical TLR4-MAPK-Stat1 cell signaling pathway is beneficial for preventing neuroinflammation and increasing Aβ clearance in AD brain (see our working model in Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Working model for the effect of Ponesimod on microglial activation and phagocytosis. Aβ42 binds to TLR4 and induces a complex with S1PR1. S1P co-activates the downstream pro-inflammatory cell signaling pathways ERK, p38 MAPK and JNK, which leads to phosphorylation activation of the transcription factors Stat1/3 and induction of neuroinflammation, particularly via gene expression of TNF-α. Ponesimod blocks S1P mediated co-activation of TLR4 and instead, leads to phagocytosis and proteolytic degradation of the receptor complex and Aβ42. In addition to inhibition of the canonical cell signaling for neuroinflammation downstream of TLR4, Ponesimod upregulates microglial phagocytosis via IL-33/Stat6 in a non-canonical cell signaling pathway, thereby contributing to persistent clearance of Aβ and alleviation of AD pathology. Generated using Biorender.

The effect of Ponesimod on neuroinflammation in vivo was clearly demonstrated by reducing the pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines TNF-α and CXCL10, while the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-33 was elevated by Ponesimod in 5XFAD mice. We found that consistent with in vitro data, Ponesimod reduced the activation of p38 MAPK in 5XFAD mouse brain by half, which suggests downregulation of the Aβ-induced TLR4-MAPK-Stat1 cell signaling pathway for pro-inflammatory cytokines in microglia (Fig. 8). The increased level of IL-33 in brain tissue from Ponesimod-treated 5XFAD mice is in line with activation of Stat6.62,63 However, the mechanism underlying the Ponesimod-induced activation of the Stat6 cell signaling pathway is currently unclear, and probably non-canonically regulated depending on the Aβ-induced crosstalk between TLR4 and S1PR1 or Ponesimod-induced internalization of the TLR4-S1PR1 receptor complex as shown in our proposed model (Fig. 8).

Our model implies that Ponesimod induces reprogramming of proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory microglia with reduced labeling of Iba-1 and increased ability of Aβ clearance. Our model is supported by data showing that Ponesimod decreases iNOS labeling of Iba-1(+) microglia and Fluoro-jade labeling of neurons, consistent with Ponesimod-induced reprogramming of microglia to a less “neurotoxic’ and more “neuroprotective” phenotype preventing neurodegeneration in the 5XFAD mouse (Supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). We found that Ponesimod reduces the number of Iba-1 labeled microglia as well as GFAP-labeled reactive astrocytes, suggesting that a similar mechanism of reprogramming may be induced in astrocytes. Decreased activation of microglia and astrocytes is concurrent with reduced amyloid plaques, suggesting that Ponesimod improves other characteristics of AD pathology such as cognition. Amelioration of AD-associated spatial memory deficits was directly confirmed by a Y-maze test using 5XFAD mice. Cognitive improvement using S1PR antagonists, particularly with FTY720, has been previously reported.64, 65, 66, 67, 68 However, there has been no comprehensive evaluation of its effect on neuroinflammatory cell signaling pathways and amyloid clearance by microglia. Our previous study was based on the effect of FTY720 on neuroinflammation induced by intracranial injection of Aβ into wild type brain, but it did not use a genetic AD mouse model.1 Most recently, Ponesimod has been shown to inhibit neuroinflammatory activation of astrocytes, however, this study was neither performed in an AD mouse model nor was the effect on microglial amyloid clearance reported.19,26 In contrast to previous studies using S1PR antagonists in AD mouse models, our study tested cognitive improvement by Ponesimod in the 5XFAD mouse model at 9 months, an age that is more relevant to the respective effect in AD patients with amyloid pathology. Therefore, our study shows strong experimental evidence that Ponesimod may be a therapeutic drug which not only reduces neuroinflammation similar to FTY720, but also enhances microglial phagocytosis and amyloid clearance in middle and late-stage AD.

Contributors

Z.Z., S.D.S. and E.B proposed the study, designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the initial draft and final versions of the paper. Z.Z conducted the immunohistochemistry, Western Blotting, and CO-IP experiments. L.Z. performed oral gavage experiments, preparation of the brain tissues and sections, maintenance, and breeding of animals. S.M.C. assisted with flow cytometry experiments. C.H analyzed the number and size of Aβ plagues, counted the reactive glial cells in brain sections. A.E assisted with PLA experiments. P.T and Z.Q. assisted with primary cell culture experiments. Z.Z and E.B have accessed and verified the data, and all authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

All the data during the current study have been shown in the manuscript and supplemental materials, and unprocessed data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding by NIH grants R01AG064234, RF1AG078338, R21AG078601, and VA grant I01BX003643. We thank Dr. Guanghu Wang for starting, obtaining the initial funding for, and advising on this study and assistance with acquiring the BV2 cells. We thank the Department of Physiology (Chair Dr. Alan Daugherty) at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY for institutional support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104713.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary Fig. S1.

A. Protein levels (immunoblot) of S1PR1 and TLR4 in human brain tissue (white matter). B. IL-33 and TNF-α levels (immunoblot) in vehicle- and Ponesimod-treated 5XFAD brain. C. TLR-4 and S1PR1 levels in the vehicle and Ponesimod-treated 5XFAD brain cortex. D. Phagocytosis of Aβ-555 (1 µM) in microglia prepared from 6-month old 5XFAD brain with or without Ponesimod (100 nM) treatment.

Supplementary Fig. S2.

A. Immunolabeling for iNOS (red) and activated microglia (Iba-1, green) using cryosections from the brain of 5XFAD mice with or without Ponesimod treatment.

Supplementary Fig. S3.

A. Aβ immunolabeling (red) and activated microglia (Iba-1, purple) in cryosections from the 5XFAD mouse brain with or without Ponesimod. B. Fluoro-jade and Neurotrace co-immunolabeling of neurons, activated microglia (Iba-1, purple) in cryosections from 5XFAD mouse brain with or without Ponesimod. C. Fluoro-jade immunolabeling of neurons (green), Aβ-immunolabeling (red) and Iba-1 labeled activated microglia (Iba-1, purple) in cryosections from 5XFAD mouse brain with or without Ponesimod.

Supplementary Fig. S4A.

Immunolabeling for Iba-1 (purple), GFAP (red), and Aβ (green) in cryosections from 5XFAD mouse brain with vehicle (A) or with Ponesimod (B).

Supplementary Fig. S4B.

Immunolabeling for Iba-1 (purple), GFAP (red), and Aβ (green) in cryosections from 5XFAD mouse brain with vehicle (A) or with Ponesimod (B).

Blotsfig1.

Original Western Blots shown in this study (Fig. 1).

Blotsfig2.

Original Western Blots shown in this study (Fig. 2).

Blotsfig4.

Original Western Blots shown in this study (Fig. 4).

Blotsfig5.

Original Western Blots shown in this study (Fig. 5).

BlotsSUPPfig 1.

Original Western Blots shown in this study (Supplementary Figs.).

References

- 1.Zhong L., Jiang X., Zhu Z., et al. Lipid transporter Spns2 promotes microglia pro-inflammatory activation in response to amyloid-beta peptide. Glia. 2019;67(3):498–511. doi: 10.1002/glia.23558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Z., Doyle T.M., Luongo L., et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 activation in astrocytes contributes to neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(21):10557–10562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1820466116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takabe K., Spiegel S. Export of sphingosine-1-phosphate and cancer progression. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(9):1839–1846. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R046656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maceyka M., Spiegel S. Sphingolipid metabolites in inflammatory disease. Nature. 2014;510(7503):58–67. doi: 10.1038/nature13475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaho V.A., Hla T. An update on the biology of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J Lipid Res. 2014;55(8):1596–1608. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R046300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendoza A., Fang V., Chen C., et al. Lymphatic endothelial S1P promotes mitochondrial function and survival in naive T cells. Nature. 2017;546(7656):158–161. doi: 10.1038/nature22352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle T.M., Chen Z., Durante M., Salvemini D. Activation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 in the spinal cord produces mechanohypersensitivity through the activation of inflammasome and IL-1beta pathway. J Pain. 2019;20(8):956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaire B.P., Bae Y.J., Choi J.W. S1P1 regulates M1/M2 polarization toward brain injury after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2019;27:522–529. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2019.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkmann V., Billich A., Baumruker T., et al. Fingolimod (FTY720): discovery and development of an oral drug to treat multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(11):883–897. doi: 10.1038/nrd3248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brinkmann V. FTY720 (fingolimod) in Multiple Sclerosis: therapeutic effects in the immune and the central nervous system. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(5):1173–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kartalou G.I., Salgueiro-Pereira A.R., Endres T., et al. Anti-inflammatory treatment with FTY720 starting after onset of symptoms reverses synaptic deficits in an AD mouse model. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(23):8957. doi: 10.3390/ijms21238957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Doorn R., Nijland P.G., Dekker N., et al. Fingolimod attenuates ceramide-induced blood-brain barrier dysfunction in multiple sclerosis by targeting reactive astrocytes. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(3):397–410. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fagan S.G., Bechet S., Dev K.K. Fingolimod rescues memory and improves pathological hallmarks in the 3xTg-AD model of alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59(3):1882–1895. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02613-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McManus R.M., Finucane O.M., Wilk M.M., Mills K.H.G., Lynch M.A. FTY720 attenuates infection-induced enhancement of abeta accumulation in APP/PS1 mice by modulating astrocytic activation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2017;12(4):670–681. doi: 10.1007/s11481-017-9753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carreras I., Aytan N., Choi J.K., et al. Dual dose-dependent effects of fingolimod in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-47287-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawicka E., Dubois G., Jarai G., et al. The sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor agonist FTY720 differentially affects the sequestration of CD4+/CD25+ T-regulatory cells and enhances their functional activity. J Immunol. 2005;175(12):7973–7980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan S., Mi Y., Pally C., et al. A monoselective sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor-1 agonist prevents allograft rejection in a stringent rat heart transplantation model. Chem Biol. 2006;13(11):1227–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi J.W., Gardell S.E., Herr D.R., et al. FTY720 (fingolimod) efficacy in an animal model of multiple sclerosis requires astrocyte sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(2):751–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014154108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kihara Y., Jonnalagadda D., Zhu Y., et al. Ponesimod inhibits astrocyte-mediated neuroinflammation and protects against cingulum demyelination via S1P1 -selective modulation. FASEB J. 2022;36(2) doi: 10.1096/fj.202101531R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behjati M., Etemadifar M., Abdar Esfahani M. Cardiovascular effects of fingolimod: a review article. Iran J Neurol. 2014;13(3):119–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chitnis T., Arnold D.L., Banwell B., et al. Trial of fingolimod versus interferon beta-1a in pediatric multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(11):1017–1027. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Ambrosio D., Freedman M.S., Prinz J. Ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator: a potential treatment for multiple sclerosis and other immune-mediated diseases. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7(1):18–33. doi: 10.1177/2040622315617354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brossard P., Derendorf H., Xu J., Maatouk H., Halabi A., Dingemanse J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator, in the first-in-human study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(6):888–896. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pouzol L., Piali L., Bernard C.C., Martinic M.M., Steiner B., Clozel M. Therapeutic potential of ponesimod alone and in combination with dimethyl fumarate in experimental models of multiple sclerosis. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2019;16(3-4):22–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alnaif A., Oiler I., D'Souza M.S. Ponesimod: an oral second-generation selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2022;57(8):956–965. doi: 10.1177/10600280221140480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang L., Guo K., Zhou J., et al. Ponesimod protects against neuronal death by suppressing the activation of A1 astrocytes in early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurochem. 2021;158(4):880–897. doi: 10.1111/jnc.15457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mockus T.E., Netherby-Winslow C.S., Atkins H.M., et al. CD8 T cells and STAT1 signaling are essential codeterminants in protection from polyomavirus encephalopathy. J Virol. 2020;94(8):e02038–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02038-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu Z.W., Zhou L.Q., Yang S., et al. FTY720 modulates microglia toward anti-inflammatory phenotype by suppressing autophagy via STAT1 pathway. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2021;41(2):353–364. doi: 10.1007/s10571-020-00856-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qin C., Fan W.H., Liu Q., et al. Fingolimod protects against ischemic white matter damage by modulating microglia toward M2 polarization via STAT3 pathway. Stroke. 2017;48(12):3336–3346. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Charan J., Kantharia N.D. How to calculate sample size in animal studies? J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2013;4(4):303–306. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.119726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmitt F.A., Nelson P.T., Abner E., et al. University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown healthy brain aging volunteers: donor characteristics, procedures and neuropathology. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9(6):724–733. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dinkins M.B., Enasko J., Hernandez C., et al. Neutral sphingomyelinase-2 deficiency ameliorates alzheimer's disease pathology and improves cognition in the 5XFAD mouse. J Neurosci. 2016;36(33):8653–8667. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1429-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adler J., Parmryd I. Quantifying colocalization by correlation: the Pearson correlation coefficient is superior to the Mander's overlap coefficient. Cytometry A. 2010;77(8):733–742. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miron J., Picard C., Frappier J., Dea D., Theroux L., Poirier J. TLR4 gene expression and pro-inflammatory cytokines in alzheimer's disease and in response to hippocampal deafferentation in rodents. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(4):1547–1556. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Calvo-Rodriguez M., de la Fuente C., Garcia-Durillo M., Garcia-Rodriguez C., Villalobos C., Nunez L. Aging and amyloid beta oligomers enhance TLR4 expression, LPS-induced Ca(2+) responses, and neuron cell death in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14(1):24. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0802-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanisch U.K. Linking STAT and TLR signaling in microglia: a new role for the histone demethylase Jmjd3. J Mol Med (Berl) 2014;92(3):197–200. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang C.T., Wu W.F., Deng Y.H., Ge J.W. Modulators of microglia activation and polarization in ischemic stroke (Review) Mol Med Rep. 2020;21(5):2006–2018. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2020.11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorina R., Font-Nieves M., Marquez-Kisinousky L., Santalucia T., Planas A.M. Astrocyte TLR4 activation induces a proinflammatory environment through the interplay between MyD88-dependent NFkappaB signaling, MAPK, and Jak1/Stat1 pathways. Glia. 2011;59(2):242–255. doi: 10.1002/glia.21094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Butturini E., Boriero D., Carcereri de Prati A., Mariotto S. STAT1 drives M1 microglia activation and neuroinflammation under hypoxia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2019;669:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cai W., Dai X., Chen J., et al. STAT6/Arg1 promotes microglia/macrophage efferocytosis and inflammation resolution in stroke mice. JCI Insight. 2019;4(20) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.131355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie L., Zhang N., Zhang Q., et al. Inflammatory factors and amyloid beta-induced microglial polarization promote inflammatory crosstalk with astrocytes. Aging (Albany NY) 2020;12(22):22538–22549. doi: 10.18632/aging.103663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachstetter A.D., Xing B., de Almeida L., Dimayuga E.R., Watterson D.M., Van Eldik L.J. Microglial p38alpha MAPK is a key regulator of proinflammatory cytokine up-regulation induced by toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands or beta-amyloid (Abeta) J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:79. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savage M.J., Lin Y.G., Ciallella J.R., Flood D.G., Scott R.W. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38 in an Alzheimer's disease model is associated with amyloid deposition. J Neurosci. 2002;22(9):3376–3385. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03376.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sclip A., Tozzi A., Abaza A., et al. c-Jun N-terminal kinase has a key role in Alzheimer disease synaptic dysfunction in vivo. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1019. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoji M., Iwakami N., Takeuchi S., et al. JNK activation is associated with intracellular beta-amyloid accumulation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;85(1–2):221–233. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sapkota A., Gaire B.P., Kang M.G., Choi J.W. S1P(2) contributes to microglial activation and M1 polarization following cerebral ischemia through ERK1/2 and JNK. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-48609-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mandala S., Hajdu R., Bergstrom J., et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002;296(5566):346–349. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Sullivan S.A., O'Sullivan C., Healy L.M., Dev K.K., Sheridan G.K. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors regulate TLR4-induced CXCL5 release from astrocytes and microglia. J Neurochem. 2018;144(6):736–747. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walter S., Letiembre M., Liu Y., et al. Role of the toll-like receptor 4 in neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;20(6):947–956. doi: 10.1159/000110455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung Y., Lopez-Benitez J., Tognoni C.M., Carreras I., Dedeoglu A. Dysregulation of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and S1P receptor 1 signaling in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 2023;1799 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2022.148171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roviezzo F., Sorrentino R., Terlizzi M., et al. Toll-like receptor 4 is essential for the expression of sphingosine-1-phosphate-dependent asthma-like disease in mice. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1336. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richard K.L., Filali M., Prefontaine P., Rivest S. Toll-like receptor 2 acts as a natural innate immune receptor to clear amyloid beta 1-42 and delay the cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28(22):5784–5793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1146-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bascunana P., Brackhan M., Mohle L., et al. Time- and sex-dependent effects of fingolimod treatment in a mouse model of alzheimer's disease. Biomolecules. 2023;13(2):331. doi: 10.3390/biom13020331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J.W., Nam H., Kim L.E., et al. TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4) activation suppresses autophagy through inhibition of FOXO3 and impairs phagocytic capacity of microglia. Autophagy. 2019;15(5):753–770. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2018.1556946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rajbhandari L., Tegenge M.A., Shrestha S., et al. Toll-like receptor 4 deficiency impairs microglial phagocytosis of degenerating axons. Glia. 2014;62(12):1982–1991. doi: 10.1002/glia.22719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu L., Xian X., Xu G., et al. Toll-like receptor 4: a promising therapeutic target for alzheimer's disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/7924199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tahara K., Kim H.D., Jin J.J., Maxwell J.A., Li L., Fukuchi K. Role of toll-like receptor signalling in Abeta uptake and clearance. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 11):3006–3019. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giunta B., Zhou Y., Hou H., Rrapo E., Fernandez F., Tan J. HIV-1 TAT inhibits microglial phagocytosis of Abeta peptide. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1(3):260–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun A., Liu M., Nguyen X.V., Bing G. P38 MAP kinase is activated at early stages in Alzheimer's disease brain. Exp Neurol. 2003;183(2):394–405. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Y., Hou H., Nikolic W.V., et al. CD45RB is a novel molecular therapeutic target to inhibit Abeta peptide-induced microglial MAPK activation. PLoS One. 2008;3(5):e2135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hensley K., Floyd R.A., Zheng N.Y., et al. p38 kinase is activated in the Alzheimer's disease brain. J Neurochem. 1999;72(5):2053–2058. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0722053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bouffi C., Rochman M., Zust C.B., et al. IL-33 markedly activates murine eosinophils by an NF-kappaB-dependent mechanism differentially dependent upon an IL-4-driven autoinflammatory loop. J Immunol. 2013;191(8):4317–4325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olde Heuvel F., Holl S., Chandrasekar A., et al. STAT6 mediates the effect of ethanol on neuroinflammatory response in TBI. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;81:228–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stessin A.M., Banu M.A., Clausi M.G., Berry N., Boockvar J.A., Ryu S. FTY720/fingolimod, an oral S1PR modulator, mitigates radiation induced cognitive deficits. Neurosci Lett. 2017;658:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang M., Hu Y., Zhang J., Zhang J. FTY720 prevents spatial memory impairment in a rat model of chronic cerebral hypoperfusion via a SIRT3-independent pathway. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12 doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.593364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weng H., Liu X., Ren Y., Li Y., Li X. Fingolimod loaded niosomes attenuates sevoflurane induced cognitive impairments. Biomed Microdevices. 2021;24(1):5. doi: 10.1007/s10544-021-00603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Langdon D.W., Tomic D., Penner I.K., et al. Baseline characteristics and effects of fingolimod on cognitive performance in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28(12):4135–4145. doi: 10.1111/ene.15081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Crivelli S.M., Luo Q., Kruining D.V., et al. FTY720 decreases ceramides levels in the brain and prevents memory impairments in a mouse model of familial Alzheimer's disease expressing APOE4. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;152 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.