Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer (PC) survivors may potentially use substances to cope with psychological distress or poorly controlled physical symptoms. Little is known, however, about the long-term risks of alcohol use disorder (AUD) or drug use disorders in men with PC.

Methods

A national cohort study was conducted in Sweden of 180 189 men diagnosed with PC between 1998 and 2017 and 1 801 890 age-matched population-based control men. AUD and drug use disorders were ascertained from nationwide records through 2018. Cox regression was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) while adjusting for sociodemographic factors and prior psychiatric disorders. Subanalyses examined differences by PC treatment from 2005 to 2017.

Results

Men with high-risk PC had increased risks of both AUD (adjusted HR = 1.44, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.33 to 1.57) and drug use disorders (adjusted HR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.67 to 2.24). Their AUD risk was highest in the first year and was no longer significantly elevated 5 years after PC diagnosis, whereas their drug use disorders risk remained elevated 10 years after PC diagnosis (adjusted HR = 2.26, 95% CI = 1.45 to 3.52), particularly opioid use disorder (adjusted HR = 3.07, 95% CI = 1.61 to 5.84). Those treated only with androgen-deprivation therapy had the highest risks of AUD (adjusted HR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.62 to 2.25) and drug use disorders (adjusted HR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.70 to 2.92). Low- or intermediate-risk PC was associated with modestly increased risks of AUD (adjusted HR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.30 to 1.46) and drug use disorders (adjusted HR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.06 to 1.34).

Conclusions

In this large cohort, men with PC had significantly increased risks of both AUD and drug use disorders, especially those with high-risk PC and treated only with androgen-deprivation therapy. PC survivors need long-term psychosocial support and timely detection and treatment of AUD and drug use disorders.

Prostate cancer (PC) is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in the United States, Europe, and many countries worldwide (1,2). More than 3.6 million men currently living in the United States have been diagnosed with PC (nearly 5 times more than any other cancers), and this number is expected to increase to more than 5 million by 2030 (3). PC survivors may use substances in an attempt to cope with psychological distress or poorly controlled physical symptoms (4). Such use could potentially lead to substance use disorders (SUDs), which may worsen quality of life and health outcomes (5,6). A better understanding of SUD risks is needed to inform psychosocial support interventions and improve outcomes in the growing number of PC survivors.

Most studies of substance use in relation to cancer have focused on alcohol or drugs as potential risk factors for cancer incidence (7-9). Less is known, however, about SUDs as potential outcomes in cancer survivors. A systematic review of 21 studies of patients with cancer (the most common sites were breast or head and neck) found that SUD rates varied widely across studies (2% (10) to 35% (11)), with a median rate of 18% for opioids and 25% for alcohol (4). Most studies, however, have been limited by lack of information about cancer treatment, inability to assess confounding, or aggregating all substances (4). SUDs have rarely been examined in men with PC, and the few studies to do so have lacked a comparison group without PC (12,13). Aggressive PC has previously been associated with increased risks of depression and suicide, which persisted 10 years after PC diagnosis (14). However, no studies have examined SUDs in PC survivors with sufficient follow-up and sample sizes to estimate long-term (≥5-year) risks and to identify the most susceptible subgroups that may benefit most from psychosocial support and other preventive interventions. Large population-based cohorts are needed to enable well-powered assessment of long-term risks of specific SUDs, susceptible time periods, and high-risk subgroups.

We sought to address these knowledge gaps using nationwide data in Sweden. Our goals were to determine the long-term risks of alcohol use disorder (AUD) and drug use disorders for men with PC with different prognoses in a large population-based cohort and to identify periods of heightened risk after PC diagnosis. We hypothesized that men with high-risk PC have increased long-term risks of both AUD and drug use disorders.

Methods

Study population and PC ascertainment

In the National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden, we identified 183 495 men who were diagnosed with PC between 1998 and 2017 (14). The NPCR captures 98% of all incident PC cases since 1998 compared with the Swedish National Cancer Register, to which reporting is mandated by law (15). The NPCR contains data on cancer characteristics, including tumor grade according to Gleason score, disease stage according to the TNM staging classification, and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level at diagnosis (16-18). We excluded 3306 (2%) men who had missing data for any of these characteristics, leaving 180 189 (98%) men for analysis (14).

PC risk groups were defined at the time of diagnosis based on a modification used by NPCR of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice Guidelines criteria (15,19). Low-risk PC was defined by clinical local stage T1 to T2, Gleason score 2 to 6, and PSA level under 10 ng/mL; intermediate-risk PC was defined by stage T1 to T2, with Gleason score 7 or PSA level 10 to 20 ng/mL. High-risk PC was defined by clinical stage T3 or T4, Gleason score of 8 or higher, or PSA of 20 ng/mL or higher at the time of diagnosis; it was further stratified as locally advanced (stage T3 and PSA 20 to <50 ng/mL), very advanced/regionally metastatic (stage T4 or N1 or PSA 50 to <100 ng/mL in the absence of distant metastases [M0 or Mx]), or distant metastases (stage M1 or PSA ≥100 ng/mL) (15,19). Primary treatment within 6 months after diagnosis also was identified from the NPCR. Androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) was further identified using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes L02AE (gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] analogues), L02BB (antiandrogens), and L02BX (other hormone antagonists) in the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register, which contains all medication prescriptions dispensed nationwide since July 1, 2005.

Each PC case was matched to 10 men randomly sampled from the general population who had the same birth year and month and were living in Sweden on the date of PC diagnosis for the respective case (ie, index date) (14). This study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden. Participant consent was not required because this study used only pseudonymized registry-based secondary data.

AUD and drug use disorders ascertainment

The primary outcomes were the earliest diagnosis of (1) AUD or (2) drug use disorders, which were ascertained from the index date (respective case’s PC diagnosis date) through December 31, 2018, and were examined separately. To enable more complete ascertainment, AUD and drug use disorders were identified using multiple sources, including International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes in the Swedish In-Patient and Out-Patient registers and primary care records; alcohol- or drug-related offenses in the Swedish Suspicion and Crime register; and medications used for AUD treatment in the Swedish Prescribed Drug Register (see Supplementary Methods, available online). The In-Patient Register contains all primary and secondary hospital discharge diagnoses, with 86% coverage of the Swedish population starting in 1973 and 100% coverage since 1987 (20). The Swedish Out-Patient Register contains all diagnoses from specialty clinics nationwide starting in 2001. Primary care diagnoses previously collected by our group (21) were available for 20% of the Swedish population starting in 1998, 45% starting in 2001, and 90% starting in 2008 and onward. The Swedish Crime and Suspicion Registers contain nationwide records of all criminal convictions since 1973 and all suspected crimes since 1998.

Diagnostic codes for drug use disorders specifically indicate “mental and behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use,” which may include opioids, sedatives/hypnotics, or nonprescription and illicit substances (eg, cannabinoids, cocaine, hallucinogens). Therefore, a patient with cancer who is prescribed opioids or sedatives/hypnotics as part of their clinical care is not counted as having a drug use disorder unless a diagnosis is also registered for a mental or behavioral disorder resulting from use of these substances.

Covariates

Other characteristics that may be associated with PC and AUD or drug use disorders were identified using Swedish national census and health registry data. Covariates included birth date (continuous and categorical by decade); birth country (Sweden/other); marital status (married/not married); education level (≤9, 10-12, >12 years); income (quartiles); region (large cities, other/Southern, other/Northern, unknown); and prior history of major depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, AUD, or drug use disorders (each ascertained from 1973 up to the index date and modeled as a separate covariate). Psychiatric disorders were ascertained from the Swedish In-Patient and Out-Patient registers and primary care records using ICD-10 codes (Supplementary Methods, available online). All covariates were more than 96% complete. Missing data were modeled as a separate category and had little effect on risk estimates because of their rarity.

Statistical analysis

Cox regression was used to compute hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for AUD or drug use disorders in men with PC compared with matched controls, while adjusting for prior AUD or drug use disorders before the index date and other covariates and stratifying on matched sets. In a secondary analysis, we explored the association between PC and “new-onset AUD” after excluding 7418 (4%) PC cases and 94 791 (5%) controls who had a prior registration of AUD before the index date or “new-onset drug use disorder” after excluding 920 (0.5%) PC cases and 13 623 (0.8%) controls who had a prior registration of drug use disorder before the index date. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by examining log-log survival plots and was satisfied in each model.

To assess periods of susceptibility, the outcomes were assessed within specific time intervals after PC diagnosis (<3, 3 to <12 months; 1 to <2, 2 to <5, 5 to <10, ≥10 years) in separate models. The outcomes were further stratified by primary treatment modality (ADT only; radical radiation therapy with or without adjuvant ADT; radical prostatectomy; or radical prostatectomy followed by radiation therapy) using treatment data from 2005 to 2017 compared with controls. ADT was further examined as GnRH analogues vs antiandrogen monotherapy. The most common specific drug use disorders (opioid and sedative/hypnotic use disorders) were also examined in separate subanalyses.

In exploratory analyses, age-specific differences were assessed by stratifying by age at the index date (<55, 55-64, 65-74, 75-84, ≥85 years) while adjusting for age as a continuous variable within each stratum. To assess for temporal changes, we also explored associations between high-risk PC and AUD or drug use disorders after stratifying on calendar year of PC diagnosis (1998-2004, 2005-2009, 2010-2017). All statistical tests were 2-sided and used a significance level of .05. All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Among 180 189 men with PC, 56% had low- or intermediate-risk PC and 44% had high-risk PC (14). Men with low- or intermediate-risk PC were diagnosed at a median (IQR) age of 67 (62-73) years and had a median (IQR) follow-up time of 7 (4-11) years. Men with high-risk PC were diagnosed at a median (IQR) age of 75 (68-81) years and had a median (IQR) follow-up time of 4 (2-8) years. Men in the control group had a median (IQR) follow-up time of 5 (2-9) years.

In 8.0 million person-years of follow-up, a total of 74 092 (4%) and 10 819 (0.5%) men (with or without PC) were identified with AUD or drug use disorders, respectively. In total, 13% of AUD cases and 11% of drug use disorder cases were identified only from the Swedish Suspicion and Crime registers and were not identifiable using only health care registries. At 5 years of follow-up, the cumulative incidences of AUD and drug use disorders, respectively, were 3% and 0.4% among men with PC and 1% and 0.2% among men in the control group. The median ages at registration of AUD or drug use disorders, respectively, were 68 and 70 years in men with low- or intermediate-risk PC, 75 and 76 years in men with high-risk PC, and 70 and 71 years in controls. Most drug use disorder diagnoses were either opioid (39%) or sedative/hypnotic (31%) use disorders, whereas the remainder were various others, including use of nonprescription substances.

Table 1 shows characteristics of men with PC, men in the control group, and all men with AUD or drug use disorders. Men with PC were more likely than controls to be Swedish born or married. Men with high-risk PC had lower education and income levels than controls, whereas men with low- or intermediate-risk PC had higher education or income levels. Men with AUD or drug use disorders were younger and more likely to be unmarried, have low income, live in large cities, or have a prior diagnosis of major depression or anxiety disorder.

Table 1.

Characteristics of men with prostate cancer and men in the control group, 1998-2018, Sweden

| High-risk PCa | Low- or intermediate-risk PCb | Controls | AUD | Drug use disorders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 78 951 | n = 101 238 | n = 1 801 890 | n = 74 092 (3.7%) | n = 10 819 (0.5%) | |

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |

| Age at index date, y | |||||

| <55 | 1372 (1.7) | 5728 (5.7) | 71 000 (3.9) | 4242 (5.7) | 1257 (11.6) |

| 55-64 | 10 791 (13.7) | 32 406 (32.0) | 431 970 (24.0) | 26 629 (35.9) | 3861 (35.7) |

| 65-74 | 27 258 (34.5) | 45 054 (44.5) | 723 120 (40.1) | 32 764 (44.2) | 3806 (35.2) |

| 75-84 | 30 272 (38.3) | 16 356 (16.2) | 466 280 (25.9) | 9672 (13.1) | 1647 (15.2) |

| ≥85 | 9258 (11.7) | 1694 (1.7) | 109 520 (6.1) | 785 (1.1) | 248 (2.3) |

| Sweden born | 72 846 (92.3) | 92 334 (91.2) | 1 573 042 (87.3) | 65 293 (88.1) | 9174 (84.8) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 54 933 (69.6) | 72 080 (71.2) | 1 141 069 (63.3) | 35 371 (47.7) | 4651 (43.0) |

| Not married | 24 018 (30.4) | 29 157 (28.8) | 606 285 (33.7) | 38 718 (52.3) | 6168 (57.0) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (<0.1) | 54 536 (3.0) | 3 (<0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Education, y | |||||

| ≤9 | 37 659 (47.7) | 32 615 (32.2) | 748 594 (41.5) | 29 030 (39.2) | 4327 (40.0) |

| 10-12 | 27 165 (34.4) | 40 885 (40.4) | 648 123 (36.0) | 31 340 (42.3) | 4700 (43.4) |

| >12 | 14 117 (17.9) | 27 727 (27.4) | 355 450 (19.7) | 13 715 (18.5) | 1791 (16.6) |

| Unknown | 10 (<0.1) | 11 (<0.1) | 49 723 (2.8) | 7 (<0.1) | 1 (<0.1) |

| Income, quartile | |||||

| 1st (highest) | 15 832 (20.1) | 39 920 (39.4) | 468 355 (26.0) | 17 406 (23.5) | 1647 (15.2) |

| 2nd | 21 091 (26.7) | 28 529 (28.2) | 462 783 (25.7) | 20 881 (28.2) | 2555 (23.6) |

| 3rd | 22 291 (28.2) | 20 252 (20.0) | 438 894 (24.4) | 22 831 (30.8) | 3904 (36.1) |

| 4th (lowest) | 19 694 (24.9) | 12 481 (12.3) | 359 227 (19.9) | 12 793 (17.3) | 2662 (24.6) |

| Unknown | 43 (0.1) | 56 (0.1) | 72 631 (4.0) | 181 (0.2) | 51 (0.5) |

| Region | |||||

| Large cities | 34 100 (43.2) | 53 073 (52.4) | 825 039 (45.8) | 41 476 (56.0) | 6364 (58.8) |

| Other/Southern | 29 884 (37.9) | 33 257 (32.9) | 618 625 (34.3) | 22 093 (29.8) | 3037 (28.1) |

| Other/Northern | 14 957 (18.9) | 14 899 (14.7) | 310 444 (17.2) | 10 512 (14.2) | 1411 (13.0) |

| Unknown | 10 (<0.1) | 9 (<0.1) | 47 782 (2.7) | 11 (<0.1) | 7 (0.1) |

| Prior psychiatric disorders | |||||

| Major depression | 3167 (4.0) | 5108 (5.1) | 91 107 (5.1) | 10 269 (13.9) | 2728 (25.2) |

| Anxiety disorder | 2814 (3.6) | 4370 (4.3) | 81 331 (4.5) | 9715 (13.1) | 2946 (27.2) |

| Bipolar disorder | 346 (0.4) | 626 (0.6) | 11 708 (0.6) | 1472 (2.0) | 670 (6.2) |

| Schizophrenia | 247 (0.3) | 235 (0.2) | 11 808 (0.7) | 822 (1.1) | 435 (4.0) |

| AUD | 5774 (7.3) | 7706 (7.6) | 159 504 (8.9) | 44 348 (59.9) | 5054 (46.7) |

| Drug use disorders | 432 (0.6) | 665 (0.7) | 16 260 (0.9) | 4800 (6.5) | 4047 (37.4) |

High-risk PC was defined by clinical stage T3-T4, Gleason score ≥8, or PSA ≥20 ng/mL at time of diagnosis. AUD = alcohol use disorder, PC = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Low-risk PC was defined by clinical stage T1-T2, Gleason score 2-6, and PSA <10 ng/mL and intermediate-risk PC by clinical stage T1-T2, with Gleason score 7 or PSA 10 to <20 ng/mL.

PC and AUD risk

Men with high-risk PC had a more than 40% higher risk of AUD across the entire follow-up period compared with controls (adjusted HR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.33 to 1.57) (Table 2). This risk was slightly higher in men with distant metastases (adjusted HR = 1.58, 95% CI = 1.26 to 1.97) than those with locally advanced disease (adjusted HR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.29 to 1.57) or very advanced/regionally metastatic disease (adjusted HR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.19 to 1.76) (Supplementary Table 1, available online). Risk of AUD was highest within the first year and was no longer significantly elevated at 5 years after PC diagnosis (Table 2). Low- or intermediate-risk PC was associated with a modestly increased risk of AUD (adjusted HR = 1.38, 95% CI = 1.30 to 1.46) that was limited to the first year after PC diagnosis.

Table 2.

Associations between prostate cancer diagnosis (1998-2017) and risk of alcohol use disorder through 2018, Sweden

| AUD, No. |

Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC cases | Controls | |||

| High-risk PC | ||||

| Entire follow-up period | 1704 | 22 914 | 1.44 (1.33 to 1.57) | <.001 |

| <3 mo | 1152 | 13 957 | 1.51 (1.36 to 1.68) | <.001 |

| 3 to <12 mo | 199 | 2661 | 1.64 (1.29 to 2.08) | <.001 |

| 1 to <2 y | 112 | 2002 | 1.10 (0.83 to 1.46) | .67 |

| 2 to <5 y | 176 | 2936 | 1.29 (1.03 to 1.61) | .03 |

| 5 to <10 y | 65 | 1276 | 1.39 (0.92 to 2.10) | .12 |

| ≥10 y | 0 | 82 | — | — |

| High-risk PC (2005-2017)b | ||||

| ADT only | 542 | — | 1.91 (1.62 to 2.25) | <.001 |

| Radiation | 330 | — | 1.25 (1.04 to 1.51) | .02 |

| Radical prostatectomy | 48 | — | 1.69 (1.05 to 2.74) | .03 |

| Radical prostatectomy and radiation | 30 | — | 1.17 (0.65 to 2.11) | .60 |

| Low- or intermediate-risk PC | ||||

| Entire follow-up period | 3477 | 44 843 | 1.38 (1.30 to 1.46) | <.001 |

| <3 mo | 2360 | 26 081 | 1.47 (1.37 to 1.57) | <.001 |

| 3 to <12 mo | 453 | 5566 | 1.42 (1.20 to 1.68) | <.001 |

| 1 to <2 y | 243 | 3949 | 1.17 (0.95 to 1.44) | .13 |

| 2 to <5 y | 328 | 6209 | 1.13 (0.95 to 1.34) | .17 |

| 5 to <10 y | 93 | 2765 | 1.05 (0.74 to 1.48) | .78 |

| ≥10 y | 0 | 273 | — | — |

| Low- or intermediate-risk PC (2005-2017)b | ||||

| Deferred treatment | 1455 | — | 1.39 (1.27 to 1.51) | <.001 |

| ADT only | 273 | — | 1.62 (1.28 to 2.04) | <.001 |

| Radiation | 483 | — | 1.76 (1.50 to 2.05) | <.001 |

| Radical prostatectomy | 255 | — | 1.85 (1.52 to 2.26) | <.001 |

| Radical prostatectomy and radiation | 86 | — | 1.54 (1.07 to 2.21) | .02 |

Adjusted for age, birth country, marital status, education, income, region, and prior history of psychiatric disorders (major depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, AUD, drug use disorder) at index date. ADT = androgen-deprivation therapy; AUD = alcohol use disorder; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; PC = prostate cancer.

Subanalysis based on treatment data available between 2005 and 2017.

In men with high-risk PC, the risk of AUD varied significantly by PC treatment (P = .004) (Table 2). Those treated only with ADT (adjusted HR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.62 to 2.25) had higher risks than those treated with radiation (adjusted HR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.04 to 1.51) or radical prostatectomy (adjusted HR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.05 to 2.74) (P = .001 and P = .64, respectively, for comparisons with ADT) (Table 2). AUD risk was significantly elevated among those treated with GnRH analogues (adjusted HR = 1.97, 95% CI = 1.64 to 2.38) or antiandrogen monotherapy (adjusted HR = 1.67, 95% CI = 1.15 to 2.42) (P = .43 for difference in hazard ratios). Very advanced/regionally metastatic PC and distant PC metastases were more common among all men treated only with ADT (17% and 16%, respectively) than among those treated with radiation (9% and 7%), radical prostatectomy (4% and 3%), or both radiation and radical prostatectomy (5% and 4%).

Among men with low- or intermediate-risk PC, the risk of AUD was significantly elevated regardless of treatment but with some heterogeneity (P = .008) (Table 2). AUD risk was slightly lower among those with primary deferred treatment (adjusted HR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.27 to 1.51) than those treated with ADT only (adjusted HR = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.28 to 2.04), radiation (adjusted HR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.50 to 2.05), or radical prostatectomy (adjusted HR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.52 to 2.26) (P = .22, P = .009, and P = .009, respectively, for comparisons with no treatment).

High-risk and low- or intermediate-risk PC were associated with significantly increased risks of AUD in men either with or without a prior registration of AUD before the index date, but those with prior AUD had a moderately higher risk (P < .01 for difference in hazard ratios). In a secondary analysis, risk of “new-onset” AUD was assessed by excluding men with a prior registration of AUD (7418 [4%] PC cases and 94 791 [5%] controls), instead of adjusting for prior AUD in the entire group, as in the main analyses. Most risk estimates were moderately reduced, but the main findings remained statistically significant, including a 1.4-fold risk among men with high-risk PC in the first year after diagnosis (Supplementary Table 2, available online).

PC and drug use disorders risk

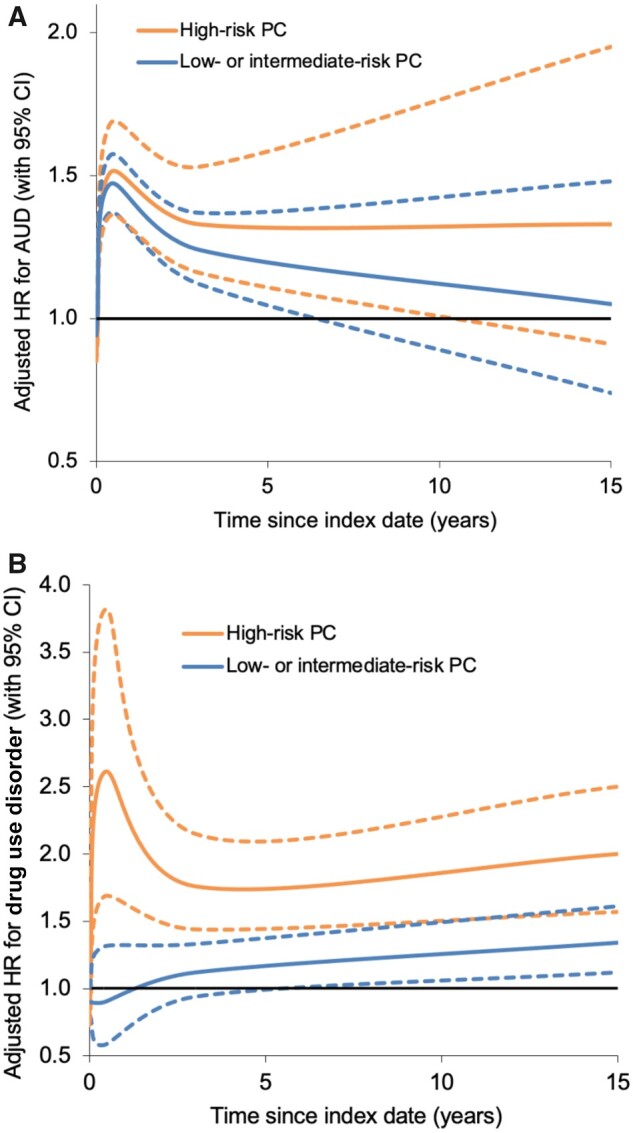

Men with high-risk PC had a nearly 2-fold risk of drug use disorders across the entire follow-up period compared with men in the control group (adjusted HR = 1.93, 95% CI = 1.67 to 2.24) (Table 3). This risk was higher in men with distant metastases (adjusted HR = 3.76, 95% CI = 2.63 to 5.36) than those with locally advanced disease (adjusted HR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.45 to 2.05) or very advanced/regionally metastatic disease (adjusted HR = 1.63, 95% CI = 1.13 to 2.35) (Supplementary Table 3, available online). The relative rate of drug use disorders peaked in the first 3 months after high-risk PC diagnosis (adjusted HR = 3.72, 95% CI = 1.93 to 7.15) but was significantly elevated even at 10 years (adjusted HR = 2.26, 95% CI = 1.45 to 3.52) (Table 3). In contrast, low- or intermediate-risk PC was associated with only a modestly increased risk of drug use disorders across the entire follow-up period (adjusted HR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.06 to 1.34) (Table 3). Figure 1 shows adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for AUD or drug use disorders by time since the index date, fitted using spline curves.

Table 3.

Associations between prostate cancer diagnosis (1998-2017) and risk of any drug use disorder through 2018, Sweden

| Drug use disorders, No. |

Adjusted HR (95% CI)a | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC cases | Controls | |||

| High-risk PC | ||||

| Entire follow-up period | 404 | 3023 | 1.93 (1.67 to 2.24) | <.001 |

| <3 mo | 39 | 744 | 3.72 (1.93 to 7.15) | <.001 |

| 3 to <12 mo | 55 | 428 | 1.54 (0.99 to 2.38) | .05 |

| 1 to <2 y | 66 | 399 | 1.83 (1.24 to 2.70) | .002 |

| 2 to <5 y | 109 | 736 | 1.89 (1.44 to 2.47) | <.001 |

| 5 to <10 y | 94 | 528 | 1.92 (1.43 to 2.57) | <.001 |

| ≥10 y | 41 | 188 | 2.26 (1.45 to 3.52) | <.001 |

| High-risk PC (2005-2017)b | ||||

| ADT only | 138 | — | 2.23 (1.70 to 2.92) | <.001 |

| Radiation | 76 | — | 1.80 (1.26 to 2.58) | .001 |

| Low- or intermediate-risk PC | ||||

| Entire follow-up period | 609 | 6620 | 1.19 (1.06 to 1.34) | .004 |

| <3 mo | 31 | 1348 | 0.97 (0.48 to 1.94) | .92 |

| 3 to <12 mo | 84 | 892 | 0.93 (0.63 to 1.38) | .71 |

| 1 to <2 y | 83 | 893 | 1.10 (0.78 to 1.55) | .60 |

| 2 to <5 y | 167 | 1620 | 1.15 (0.92 to 1.43) | .23 |

| 5 to <10 y | 163 | 1350 | 1.39 (1.11 to 1.73) | .004 |

| ≥10 y | 81 | 517 | 1.26 (0.92 to 1.72) | .16 |

| Low- or intermediate-risk PC (2005-2017)b | ||||

| Deferred treatment | 246 | — | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.35) | .31 |

| ADT only | 61 | — | 2.30 (1.48 to 3.57) | <.001 |

| Radiation | 70 | — | 0.91 (0.63 to 1.32) | .63 |

Adjusted for age, birth country, marital status, education, income, region, and prior history of psychiatric disorders (major depression, anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, AUD, drug use disorder) at index date. ADT = androgen-deprivation therapy; AUD = alcohol use disorder; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; PC = prostate cancer.

Subanalysis based on treatment data available between 2005 and 2017.

Figure 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios for AUD (A) or drug use disorders (B) associated with high-risk PC or low- to intermediate-risk PC by time since index date, 1998-2018, Sweden (dotted lines represent 95% CI). AUD = alcohol use disorder; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; PC = prostate cancer.

Among men with high-risk PC, the risk of drug use disorders was significantly elevated in those treated with ADT only (adjusted HR = 2.23, 95% CI = 1.70 to 2.92) or with radiation (adjusted HR = 1.80, 95% CI = 1.26 to 2.58) (P = .36 for difference in hazard ratios) (Table 3). Drug use disorders risk was significantly increased in men treated with GnRH analogues (adjusted HR = 2.44, 95% CI = 1.82 to 3.27) but not with antiandrogen monotherapy (adjusted HR = 1.28, 95% CI = 0.60 to 2.70). All other treatment categories had too few drug use disorder cases for meaningful analysis. Men with low- or intermediate-risk PC treated only with ADT also had a significantly increased risk of drug use disorders (adjusted HR = 2.30, 95% CI = 1.48 to 3.57), particularly those treated with GnRH analogues (adjusted HR = 2.66, 95% CI = 1.53 to 4.65).

Associations between high-risk or low- or intermediate-risk PC and drug use disorders did not vary significantly by whether there was a prior registration of drug use disorder before the index date (P > .05 for differences in hazard ratios). In a secondary analysis, new-onset drug use disorders were assessed by excluding men with a prior registration of drug use disorder (920 [0.5%] PC cases and 13 623 [0.8%] controls) as an alternative to adjusting for prior drug use disorder, as in the main analyses. Most risk estimates were little changed (Supplementary Table 4, available online). Across the entire follow-up period, the adjusted hazard ratio for new-onset drug use disorders in men with high-risk PC was 1.86 (95% CI = 1.60 to 2.15).

In analyses of specific drug use disorders, men with high-risk PC had an increased risk of opioid use disorder (OUD) across the entire follow-up period (adjusted HR = 1.69, 95% CI = 1.39 to 2.06) and especially at 5 to 10 years (adjusted HR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.39 to 2.97) and 10 years and beyond (adjusted HR = 3.07, 95% CI = 1.61 to 5.84) after PC diagnosis (Supplementary Table 5, available online). They also had an increased risk of sedative/hypnotic use disorders in the first 3 months after PC diagnosis (adjusted HR = 3.19, 95% CI = 1.24 to 8.22) but not across the entire follow-up period (adjusted HR = 1.20, 95% CI = 0.90 to 1.59), except among those treated only with ADT (adjusted HR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.14 to 3.33) (Supplementary Table 6, available online).

Other secondary analyses

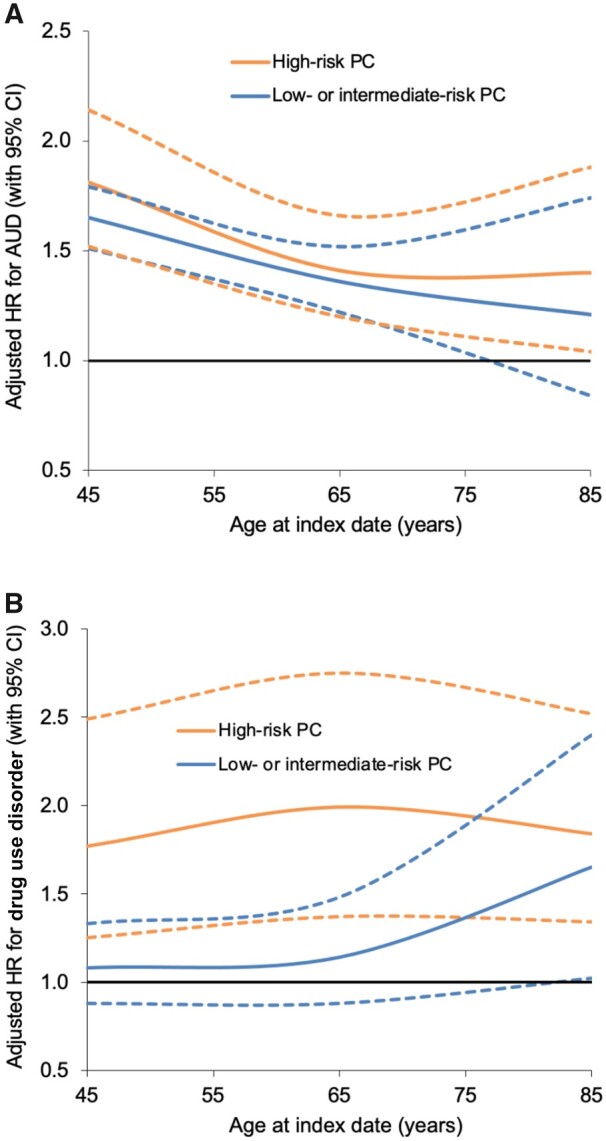

Stratifying on age at PC diagnosis, risks of either AUD or drug use disorders had significant heterogeneity (P < .001). For low- or intermediate-risk and high-risk PC, the relative rate for AUD was highest in men diagnosed with PC younger than 55 years of age (Supplementary Table 7, available online). In contrast, the relative rate of drug use disorders was highest in men diagnosed with low- or intermediate-risk PC at older ages (≥75 years) and was consistently elevated across all men 65 years of age or older with high-risk PC (Supplementary Table 8, available online). Figure 2 shows adjusted hazard ratios for AUD or drug use disorders associated with high-risk PC by age at the index date.

Figure 2.

Adjusted hazard ratios for AUD (A) or drug use disorders (B) associated with high-risk PC or low- to intermediate-risk PC by age at index date, 1998-2018, Sweden (dotted lines represent 95% CI). AUD = alcohol use disorder; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; PC = prostate cancer.

Stratifying by year of PC diagnosis, no consistent temporal patterns were found. The risk of AUD appeared to peak among men diagnosed with high-risk PC in 2005 to 2009 (adjusted HR = 1.81, 95% CI = 1.55 to 2.11), whereas drug use disorders risk peaked among those diagnosed between 1998 and 2004 (adjusted HR = 2.32, 95% CI = 1.37 to 3.92) or between 2010 and 2017 (adjusted HR = 2.27, 95% CI = 1.56 to 3.31) (Supplementary Table 9, available online).

Discussion

In this large, population-based cohort, men diagnosed with high-risk PC had more than a 40% subsequent increased risk of AUD and 90% increased risk of drug use disorders compared with men in the control group without PC, after adjusting for sociodemographic factors and prior psychiatric diagnoses. Their risk of AUD was highest in the first year and was no longer significantly elevated at 5 years after PC diagnosis, whereas their risk of drug use disorders (particularly OUD) remained elevated 10 years after PC diagnosis. Men treated with ADT had the highest risks of both AUD and drug use disorders. Men with low- or intermediate-risk PC had only modestly increased risks of AUD and drug use disorders.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine long-term (≥5-year) risks of AUD and drug use disorders associated with PC in a large, population-based cohort. A previous study of 14 277 US Medicare patients 66 years of age or older with advanced-stage PC showed an 11% overall prevalence of SUDs but did not include a comparison group without PC (12). We previously reported that men with high-risk PC had approximately an 80% increased risk of major depression and more than 2-fold risk of death by suicide compared with same-aged men without PC and that these risks remained elevated 10 years after PC diagnosis (14). Other studies also have reported a high prevalence of psychosocial distress among patients with PC but without assessing SUDs. A meta-analysis of 27 studies with a pooled sample size of 4494 men with PC, for example, reported a 15% to 18% prevalence of clinically significant depression (22). A Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare study of 50 856 men with localized PC and 2 to 7 years of follow-up reported that 20% developed mental illness (a composite of depression, anxiety, and suicide) (23).

The present study extends prior evidence by examining long-term risks of specific SUDs and periods of heightened risk in different PC risk groups and by PC treatment. Men with high-risk PC had substantially increased risks of AUD that were highest in the first year and even higher relative rates of drug use disorders than men in the control group, especially sedatives/hypnotics (3-fold) at less than 3 months and opioids (3-fold) at 10 years or more after PC diagnosis. Moreover, those treated only with ADT had the highest risks of AUD (1.9-fold) and drug use disorders (2.2-fold) and specifically risks of sedative/hypnotic use disorder (1.9-fold) and OUD (2.2-fold). These findings were consistent with elevated risks of major depression and suicide that we previously reported among men treated with ADT (14) and with a prior meta-analysis that reported an association between ADT use and depression, even in men with localized disease (24). The higher risks observed in men who received noncurative ADT may be related to side effects of ADT (25) as well as more aggressive cancers in such men with ensuing poorer prognosis and less hope of cure than men treated with curatively intended therapy, such as radical radiation therapy or radical prostatectomy. In this cohort, men treated only with ADT were more likely to have very advanced or metastatic disease than those treated with radiation or radical prostatectomy. Despite elevated relative risks in particular among men with advanced PC and men treated with ADT, however, it should be noted that the cumulative incidences of AUD and drug use disorders were modest both in men with PC and in men in the control group.

PC survivors may potentially use substances in an attempt to cope with psychological distress or poorly controlled physical symptoms (22,26-28). The stronger associations for drug use disorders (including OUD and sedative/hypnotic use disorder) than for AUD suggest that these findings may be partly related to cancer pain management (4). These findings have important clinical implications because substance use may compromise cancer treatment adherence (29), symptom management (30), quality of life (31), and long-term health outcomes (12,13). AUD and drug use disorders have previously been associated with higher health care utilization, cost of care, and mortality in men with high-risk PC (12). Follow-up care for PC survivors should include psychosocial support, particularly shortly after PC diagnosis, to help reduce psychosocial distress and prevent the development of AUD or drug use disorders. We found no decrease in risk of AUD or drug use disorders in later calendar periods, which may suggest no major improvement in psychosocial support for men with PC. American Cancer Society guidelines currently recommend alcohol use counseling and screening at least annually for psychosocial distress and depression (but not specifically AUD and drug use disorders) in men with PC (32). The United States Preventive Services Task Force also recommends screening for AUD and drug use disorders in all adult primary care settings (33-35). Validated screening tools exist that can quickly and accurately identify AUD and drug use disorders in primary care (36-38). Psychosocial support and clinical screening for AUD and drug use disorders are warranted in PC survivors, especially men with high-risk disease and ADT use. Positive screens should be followed by a brief intervention focused on patient education and prompt referral for treatment (36-38), which may improve long-term health outcomes (12,13).

A key strength of this study was its large, national cohort design, which provided the high statistical power needed to examine PC risk groups, narrowly defined periods of susceptibility, and potential heterogeneity of risk by PC treatment. The inclusion of AUD and drug use disorder diagnoses from primary care, where most cases are diagnosed (21), enabled more complete ascertainment than in prior studies and thus more valid risk estimates. The availability of alcohol- and drug-related offenses from the Swedish Suspicion and Crime registers also enabled more complete capture of cases that could not be identified using only health care records. We were able to assess long-term risks of both AUD and drug use disorders in a national population while controlling for multiple potential confounders. Previously reported incidences of AUD, drug use disorders, and other major mental health outcomes are comparable between Sweden and the United States (21,39,40).

This study also had certain limitations. AUD and drug use disorders were identified from ICD-10 codes and other registry sources, but more detailed clinical data were unavailable for validation. Their validity, however, has previously been supported by their prevalence, sex ratio, sibling correlations, and associations with well-documented risk factors (21). It is possible that SUDs were more likely to be identified in men with PC because of greater contact with the health care system (ie, detection bias), particularly AUD in the first year after PC diagnosis. Certain alcohol- or drug-related offenses in the Swedish Suspicion and Crime registers could also represent risky substance use rather than a true SUD. Despite a large cohort that enabled key subgroup analyses, statistical power for certain subgroups was still limited. This study also was performed in Sweden and will need replication in more diverse populations to explore for racial/ethnic heterogeneity. In a previous US study, SUDs had higher prevalences in people from racial/ethnic minoritized groups with PC (13).

In this large population-based cohort, men with PC had increased risks of both AUD and drug use disorders, especially those with high-risk PC and ADT use. Among men with high-risk PC, the risk of drug use disorders (particularly OUD) remained elevated 10 years and longer after PC diagnosis. PC survivors need psychosocial support, particularly shortly after PC diagnosis, and long-term follow-up for prevention, timely detection, and treatment of AUD and drug use disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by the continuous work of the NPCR steering group: Ingela Franck Lissbrant (chair), David Robinson, Johan Styrke, Johan Stranne, Jon Kindblom, Camilla Thellenberg, Andreas Josefsson, Ingrida Verbiene, Hampus Nugin, Stefan Carlsson, Anna Kristiansen, Mats Andén, Thomas Jiborn, Olof Ståhl, Olof Akre, Per Fransson, Eva Johansson, Magnus Törnblom, Fredrik Jäderling, Marie Hjälm Eriksson, Lotta Renström, Jonas Hugosson, Ola Bratt, Maria Nyberg, Fredrik Sandin, Camilla Byström, Mia Brus, Mats Lambe, Anna Hedström, Nina Hageman, Christofer Lagerros, and patient representatives Hans Joelsson and Gert Malmberg.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Lund University in Sweden (No. 2008/471 and later amendments).

The funders had no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the writing or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Contributor Information

Casey Crump, Departments of Family Medicine and Community Health and of Population Health Science and Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA.

Pär Stattin, Department of Surgical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

James D Brooks, Department of Urology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA.

Jan Sundquist, Departments of Family Medicine and Community Health and of Population Health Science and Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA; Center for Primary Health Care Research, Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Alexis C Edwards, Department of Psychiatry, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA.

Weiva Sieh, Department of Epidemiology, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Kristina Sundquist, Departments of Family Medicine and Community Health and of Population Health Science and Policy, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA; Center for Primary Health Care Research, Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Data availability

The national registry data on which this study was based were analyzed under strict confidentiality agreements with Swedish authorities. Because of ethical concerns, the supporting data cannot be made openly available. Further information about the health registers is available from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/.

Author contributions

Casey Crump, MD, PhD (Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing), Pär Stattin, MD, PhD (Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Writing—review & editing), James D. Brooks, MD (Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Jan Sundquist, MD, PhD (Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Writing—review & editing), Alexis C. Edwards, PhD (Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Weiva Sieh, MD, PhD (Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—review & editing), Kristina Sundquist, MD, PhD (Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Supervision; Writing—review & editing)

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute [R01 CA269553 to C.C., W.S., and K.S.] and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [R01 AA027522 to A.E. and K.S.] at the National Institutes of Health; and the Swedish Research Council.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363-385. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yusufov M, Braun IM, Pirl WF. A systematic review of substance use and substance use disorders in patients with cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;60:128-136. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J, Härter M. Quality of life in medically ill persons with comorbid mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2011;80(5):275-286. doi: 10.1159/000323404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baumeister H, Balke K, Härter M. Psychiatric and somatic comorbidities are negatively associated with quality of life in physically ill patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(11):1090-1100. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scoccianti C, Lauby-Secretan B, Bello PY, Chajes V, Romieu I. Female breast cancer and alcohol consumption: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(3 suppl 1):S16-S25. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hashibe M, Straif K, Tashkin DP, Morgenstern H, Greenald S, Zhang ZF. Epidemiologic review of marijuana use and cancer risk. Alcohol. 2005;35(3):265-275. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dahlman D, Li X, Crump C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. Drug use disorder and risk of incident and fatal prostate cancer among Swedish men: a nationwide epidemiological study. Cancer Causes Control. 2022;33(2):213-222. doi: 10.1007/s10552-021-01513-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Choflet A, Narang AK, Herald Hoofring L, et al. Prevalence of substance use in patients with cancer receiving radiation therapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20(4):397-402. doi: 10.1188/16.CJON.397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kangas M, Henry JL, Bryant RA. The course of psychological disorders in the 1st year after cancer diagnosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(4):763-768. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chhatre S, Metzger DS, Malkowicz SB, Woody G, Jayadevappa R. Substance use disorder and its effects on outcomes in men with advanced-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(21):3338-3345. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chhatre S, Jayadevappa R. Racial and ethnic disparities in substance use disorders and outcomes in elderly prostate cancer patients. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2018;17(2):135-149. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2016.1160019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Crump C, Stattin P, Brooks JD, et al. Long-term risks of depression and suicide in men with prostate cancer: a national cohort study [published online ahead of print May 9, 2023]. Eur Urol. 2023;S0302-2838(23)02787-2. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Hemelrijck M, Wigertz A, Sandin F, et al. ; NPCR and PCBaSe Sweden. Cohort profile: the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden and Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden 2.0. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):956-967. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tomic K, Sandin F, Wigertz A, Robinson D, Lambe M, Stattin P. Evaluation of data quality in the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(1):101-111. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tomic K, Berglund A, Robinson D, et al. Capture rate and representativity of the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2015;54(2):158-163. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2014.939299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tomic K, Westerberg M, Robinson D, Garmo H, Stattin P. Proportion and characteristics of men with unknown risk category in the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(12):1461-1466. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2016.1234716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(2):162-200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish National Inpatient Register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sundquist J, Ohlsson H, Sundquist K, Kendler KS. Common adult psychiatric disorders in Swedish primary care where most mental health patients are treated. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):235. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Watts S, Leydon G, Birch B, et al. Depression and anxiety in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e003901. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ravi P, Karakiewicz PI, Roghmann F, et al. Mental health outcomes in elderly men with prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(8):1333-1340. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nead KT, Sinha S, Yang DD, Nguyen PL. Association of androgen deprivation therapy and depression in the treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Oncol. 2017;35(11):664.e1-664.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nguyen PL, Alibhai SM, Basaria S, et al. Adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy and strategies to mitigate them. Eur Urol. 2015;67(5):825-836. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zenger M, Lehmann-Laue A, Stolzenburg JU, Schwalenberg T, Ried A, Hinz A. The relationship of quality of life and distress in prostate cancer patients compared to the general population. Psychosoc Med. 2010;7:Doc02. doi: 10.3205/psm000064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brunckhorst O, Hashemi S, Martin A, et al. Depression, anxiety, and suicidality in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2021;24(2):281-289. doi: 10.1038/s41391-020-00286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guo Z, Gan S, Li Y, et al. Incidence and risk factors of suicide after a prostate cancer diagnosis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21(4):499-508. doi: 10.1038/s41391-018-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Passik SD, Portenoy RK, Ricketts PL. Substance abuse issues in cancer patients. Part 1: prevalence and diagnosis. Oncology (Williston Park). 1998;12(4):517-521, 524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ling W, Mooney L, Hillhouse M. Prescription opioid abuse, pain and addiction: clinical issues and implications. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2011;30(3):300-305. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rudolf H, Watts J. Quality of life in substance abuse and dependency. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2002;14(3):190-197. doi: 10.1080/09540260220144975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Skolarus TA, Wolf AM, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society prostate cancer survivorship care guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):225-249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1899-1909. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. O’Connor EA, Perdue LA, Senger CA, et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320(18):1910-1928. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. US Preventive Services Task Force; Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for unhealthy drug use: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2301-2309. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McNeely J, Hamilton L. Screening for unhealthy alcohol and drug use in general medicine settings. Med Clin North Am. 2022;106(1):13-28. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2021.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knox J, Hasin DS, Larson FRR, Kranzler HR. Prevention, screening, and treatment for heavy drinking and alcohol use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(12):1054-1067. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30213-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Han BH, Moore AA. Prevention and screening of unhealthy substance use by older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(1):117-129. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kessler RC, Wang PS. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:115-129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Global Health Observatory data repository: suicide rate estimates, age-standardized. Estimates by country. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHSUICIDEASDR?lang=en. Updated February 9, 2021. Accessed January 23, 2023.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The national registry data on which this study was based were analyzed under strict confidentiality agreements with Swedish authorities. Because of ethical concerns, the supporting data cannot be made openly available. Further information about the health registers is available from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/en/statistics-and-data/registers/.