Abstract

Background

Mycoplasma genitalium has a tendency to develop macrolide and quinolone resistance.

Objectives

We investigated the microbiological cure rate of a 7 day course of sitafloxacin for the treatment of rectal and urogenital infections in MSM.

Patients and methods

This open-label, prospective cohort study was conducted at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan from January 2019 to August 2022. Patients with M. genitalium urogenital or rectal infections were included. The patients were treated with sitafloxacin 200 mg daily for 7 days. M. genitalium isolates were tested for parC, gyrA and 23S rRNA resistance-associated mutations.

Results

In total, 180 patients (median age, 35 years) were included in this study, of whom 77.0% (97/126) harboured parC mutations, including 71.4% (90/126) with G248T(S83I) in parC, and 22.5% (27/120) harboured gyrA mutations. The median time to test of cure was 21 days. The overall microbiological cure rate was 87.8%. The cure rate was 100% for microbes harbouring parC and gyrA WTs, 92.9% for microbes harbouring parC G248T(S83I) and gyrA WT, and 41.7% for microbes harbouring parC G248T(S83I) and gyrA with mutations. The cure rate did not differ significantly between urogenital and rectal infection (P = 0.359).

Conclusions

Sitafloxacin monotherapy was highly effective against infection caused by M. genitalium, except strains with combined parC and gyrA mutations. Sitafloxacin monotherapy can be used as a first-line treatment for M. genitalium infections in settings with a high prevalence of parC mutations and a low prevalence of gyrA mutations.

Introduction

Mycoplasma genitalium, a pathogen that causes sexually transmitted infections (STIs), causes urethritis in men and cervicitis and pelvic inflammatory disease in women.1,2 Although controversial, proctitis has also been associated with this pathogen, particularly in MSM.3,4 M. genitalium infection is being increasingly researched as the pathogen is developing antimicrobial resistance. The prevalence of M. genitalium strains carrying resistance-associated mutations has been increasing globally over the past few decades. The prevalence of resistant strains varies by region; it is higher in the Asian and Western Pacific regions, including Australia, New Zealand and Japan, than in Europe.5 Recent studies from the countries with a high prevalence of resistant strains have found that the prevalence of strains carrying macrolide resistance-associated mutations (MRMs) and quinolone resistance-associated mutations (QRMs) is 66.4%–89.6% and 19.0%–77.7%, respectively.6-9,10 MRMs are associated with failure of azithromycin treatment and involve mutations at position 2071 or 2072 of the 23S rRNA gene,11 whereas QRMs are associated with a mutation in the QRDR. Mutations in ParC proteins, such as S83 and D87, and GyrA proteins, such as M95, G93 and D99, are associated with moxifloxacin and sitafloxacin treatment failure.12-15 Current guidelines recommend resistance-guided therapy when resistance testing is available; otherwise, sequential therapy with doxycycline followed by a fluoroquinolone is recommended.16,17 In Japan, resistance testing for M. genitalium is not commercially available, and owing to the high prevalence of MRM-harbouring strains, sitafloxacin is used as first-line therapy. Sitafloxacin is a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone approved for use in Japan; however, it has not been approved in most other countries. It is more effective than moxifloxacin, which is approved in many countries such as Australia and the USA, for treating M. genitalium infections with resistance mutations.14,15,18 In terms of safety, sitafloxacin 200 mg daily is generally well tolerated, with the most common side effects being gastrointestinal problems and liver function disorders.19,20 A randomized trial comparing sitafloxacin with moxifloxacin found that the two drugs had a similar incidence of adverse effects.19 Additionally, sitafloxacin and moxifloxacin are less associated with tendon rupture, which is an adverse effect of the second-generation quinolones21; however, data on the safety of sitafloxacin are limited owing to its low availability. The clinical effectiveness of sitafloxacin monotherapy is unclear because the current knowledge of effectiveness is based on the results of sequential therapy with doxycycline followed by sitafloxacin or an in vitro MIC assay. The role of initial doxycycline administration in sequential therapy is to reduce M. genitalium load and, presumably, increase the microbiological cure rate of the macrolide-based regimen.22,23 In contrast, monotherapy is a simple regimen with advantages in terms of cost-effectiveness and adherence.

Available evidence for the effectiveness of M. genitalium therapy is based on its application in urogenital infection treatment, and the effectiveness of sitafloxacin for treating rectal infection remains unknown. In a previous study, moxifloxacin (92%) was more effective than azithromycin (35%) in treating rectal infections, suggesting a difference in its effectiveness according to the anatomical site.3 Information on the effectiveness of sitafloxacin for treating rectal infections is lacking.

During the study period, we used two diagnostic assays for M. genitalium. The PCR-based Invader kit was available in Japan and some other countries from 2014; however, its performance relative to PCR has not been evaluated using a third test.24 In contrast, the Aptima assay has been approved in most countries and has higher sensitivity than the mgpB quantitative PCR as a reference.25-27 The aim of this study was to investigate the microbiological cure rate of a 7 day course of sitafloxacin for the treatment of rectal and urogenital infections in MSM.

Patients and methods

Population

We conducted a prospective cohort study in two outpatient clinics of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM), Tokyo, Japan, the AIDS Clinical Center (ACC) and the Sexual Health Clinic (SHC), between 1 January 2019 and 31 August 2022. The criteria for inclusion in the ACC cohort were: individuals aged 18 years or older receiving treatment for HIV infection. The criteria for inclusion in the SHC cohort were MSM aged 18 years or older without HIV infection who were regularly screened for HIV and other STIs. Individuals who expressed interest in participating were included. No specific exclusion criteria were applied for this study. A test for M. genitalium was performed annually. If participants developed symptoms of possible M. genitalium infection, they were tested. In the two study populations, MSM diagnosed to have M. genitalium infection from urine samples or rectal swabs using a PCR assay were evaluated and administered sitafloxacin 200 mg daily for 7 days. All participants provided written informed consent for participation in this study. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of NCGM (NCGM-G-003350-00, NCGM-G-002091-00) and conducted according to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its later amendments.

From 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2020, the PCR-based Invader kit (LSI Medience Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used for the diagnostic assay; thereafter, the Aptima Mycoplasma genitalium assay (Hologic Inc. San Diego, CA, USA) was used until the end of the study.24,25 The participants were requested to return for a test of cure (TOC) 21 days after completing the therapy. Microbiological cure was defined as a negative TOC after completing the regimen. Once a microbiological cure was achieved, participants were able to receive sitafloxacin treatment again. Moreover, for the assessment of M. genitalium load, the participants were requested to submit a urine or rectal swab sample before initiating treatment. Bacterial load was measured as reported previously.28 Data on participant demographics were obtained from medical records.

Detection of resistance

M. genitalium-positive samples before the initiation of treatment were used for resistance detection. Resistance-associated mutations were detected by targeted amplification of the 23S rRNA V domain and relevant regions of gyrA and parC, as previously described,14,18 followed by Sanger sequencing, performed using the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan) on the Applied Biosystems 3500 Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The obtained sequences were compared against the corresponding target regions of the complete genome of M. genitalium G37 (GenBank: L43967.2) to detect and identify mutations. Mutations at positions S83 and D87 in parC and mutations at positions M95, G93 and D99 in gyrA were defined as resistance-associated mutations.12-15, 18 In cases where treatment failed, the number of short tandem repeats (STRs) in the protein MG309 was analysed to distinguish between reinfection and relapse, as previously reported.29

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of the participants extracted from medical records were compared across different samples and HIV status. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables, and the Mann–Whitney U-test or Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare continuous variables between groups. Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The proportion of patients with microbiological cure and 95% CI were calculated using exact methods. Bacterial loads were compared across different samples and parC mutation status. However, as the number of urine samples was limited, analysis of the bacterial load was not performed according to the parC mutation status. Patients with both rectal and urinary infections had the results from each site analysed separately, and TOC was evaluated at the same site.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

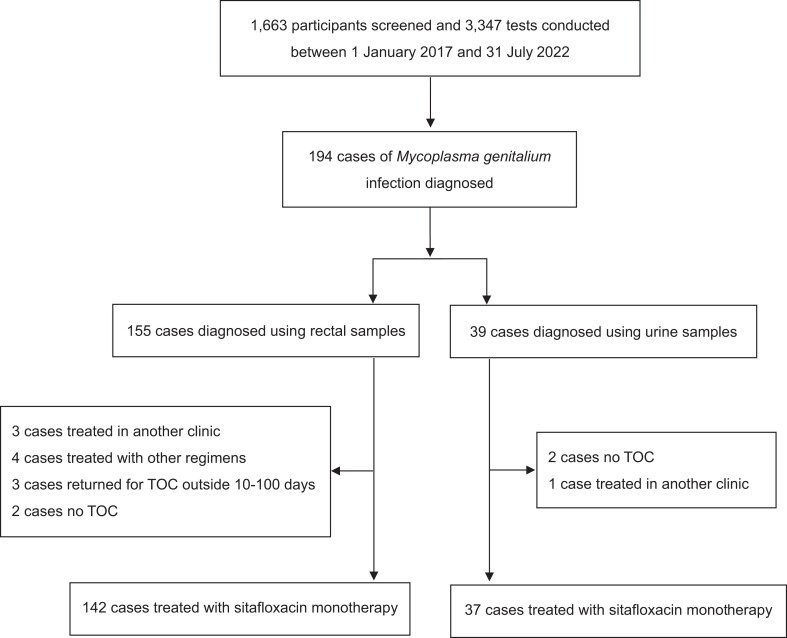

In total, 1663 study participants were screened and 3347 tests were performed from 1 January 2019 to 31 August 2022 (Figure 1). One-hundred-and-ninety-one patients were diagnosed to have M. genitalium infection; among them, 156 tested positive for rectal infections and 41 tested positive for urogenital infections, including 6 who tested positive for both rectal and urogenital infections. One-hundred-and-eighty patients with M. genitalium infections (142 with rectal and 38 with urogenital infections, including 6 with both) were treated with sitafloxacin monotherapy and included in the analysis. Among those treated, eight received treatment twice. The median age of the participants was 35 (IQR, 29–42) years (Table 1), of whom 40.0% had HIV coinfection and 60.0% did not. In patients with HIV infection, the median CD4 count was 609 (IQR, 431–772) cells/µL, and 93.0% had an HIV viral load of less than 200 copies/mL. The median time to TOC was 21 (IQR, 21–28) days. Symptoms were significantly more frequent in patients with urogenital infections than in those with rectal infections (31.6% versus 11.3%; P = 0.002). Of the patients with M. genitalium infection, 22.8% were coinfected with either Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae—19.0% with C. trachomatis coinfection and 6.1% with N. gonorrhoeae coinfection. In patients with N. gonorrhoeae coinfection, urogenital infection was significantly more frequent than anal infection (P = 0.005). Antibiotic exposure potentially effective against M. genitalium within 1 month preceding its diagnosis was observed in six cases; three cases were prescribed doxycycline for C. trachomatis, two cases metronidazole for amoebiasis, and one case levofloxacin for acute urethritis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the selection of sitafloxacin monotherapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with M. genitalium infections according to the infection site

| Total, n = 180 | Anal, n = 142 | Urogenital, n = 38 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 35 (29–42) | 35 (29–42) | 36 (29–42) | 0.769 |

| Time to TOC (days), median (IQR) | 21 (21–28) | 22 (21–30) | 21 (21–28) | 0.431 |

| Symptomatic, % (proportion) | 15.6 (28/180) | 11.3 (16/142) | 31.6 (12/38) | 0.002 |

| HIV-positive, % (proportion) | 40.0 (72/180) | 40.8 (58/142) | 36.8 (14/38) | 0.655 |

| CD4 count (cells/µL), median (IQR)a | 609 (431–772) | 621.5 (425–766) | 583.5 (505–784) | 0.720 |

| Proportion of viral load <200 copies/mL, % (proportion) | 93.1 (67/72) | 93.1 (54/58) | 92.9 (13/14) | 0.975 |

| MRMs, % (proportion) | 89.4 (126/141) | 89.0 (97/109) | 90.6 (29/32) | 0.792 |

| Coinfection with C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae, % (proportion) | 22.8 (41/180) | 20.4 (29/142) | 31.6 (12/38) | 0.145 |

| Coinfection with C. trachomatis, % (proportion) | 19.4 (35/180) | 19.0 (27/142) | 21.1 (8/38) | 0.778 |

| Coinfection with N. gonorrhoeae, % (proportion) | 6.1 (11/180) | 3.5 (5/142) | 15.8 (6/38) | 0.005 |

P values of <0.05 indicate statistical significance.

Only HIV-positive individuals.

Resistance-associated mutations

Of the 180 positive samples, 141 (78.3%), 126 (70.0%) and 119 (66.1%) were successfully analysed for MRMs, parC mutations and gyrA mutations, respectively. MRMs were detected in 89.4% (126/141) of the samples; their prevalence did not differ significantly according to the infection site. parC mutations were detected in 77.0% (97/126) of the samples, with G248T (S83I) being the most prevalent parC mutation, present in 71.4% (90/126) of the samples. Other parC mutations included A247C(S83R) (2.4%, 3/126), G248A (S83N) (0.79%, 1/126) and G259A (D87N) (2.4%, 3/126). WT parC was found in 23.0% (29/126) of the samples. gyrA mutations were identified in 22.5% (27/120) of the samples, with G285T (M95I) being the most common, present in 15.1% (18/119) of the samples. This was followed by G277T (G93C) and G295A (D99N), each found in 2.5% (3/119) of the samples. The G295T (D99Y) and A296G (D99G) mutations, as well as the combined G285C (M95I) and G295A (D99N) mutation, were less common, each detected in only one sample (0.84%). The WT gyrA was present in 77.3% (92/119) of the samples. Of the samples tested, 87/113 (77.0%) strains harboured MRM and parC mutations, 24/113 (21.2%) harboured parC and gyrA mutations, and 22/111 (19.8%) harboured triple MRM, parC and gyrA mutations. Four participants could not be evaluated for resistance mutations because they did not provide a rectal sample.

Effectiveness of sitafloxacin treatment

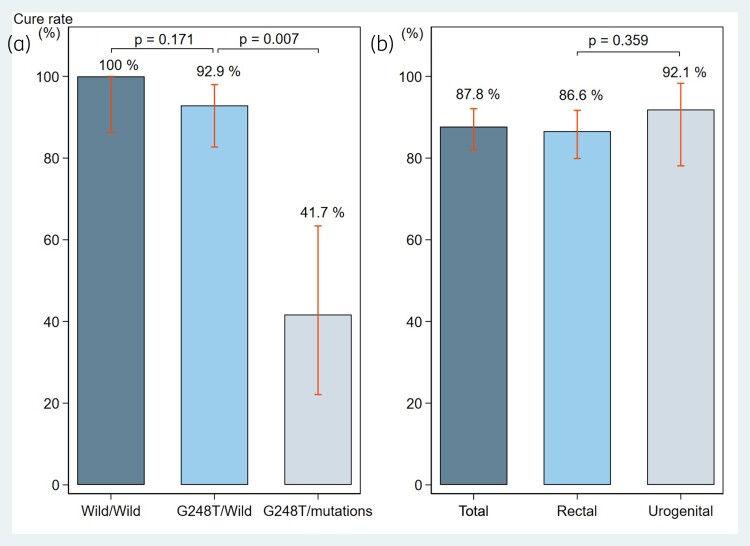

The overall microbiological cure rate with sitafloxacin in patients with M. genitalium infection was 87.8% (158/180; 95% CI, 82.1%–92.2%) (Table 2). The cure rate for rectal and urogenital M. genitalium infection was 86.6% (123/142; 95% CI, 79.9%–91.7%) and 92.1% (35/38; 95% CI, 78.6%–98.3%), respectively (Figure 2) (Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC Online). The cure rate did not differ significantly according to the infection site (P = 0.359). All patients with infections at both sites were successfully treated. The overall cure rate in patients infected with strains carrying both WT parC and gyrA was 100% (25/25), including 22 rectal and 3 urogenital infections. The overall cure rate in patients infected with strains carrying G248T (S83I) in parC and WT gyrA was 92.9% (52/56). The cure rates did not differ significantly in patients infected with strains carrying G248T (S83I) in parC with WT gyrA and those infected with WT parC and gyrA (P = 0.171). Furthermore, the overall cure rate in patients infected with strains carrying G248T (S83I) in parC and a confirmed mutation in gyrA was 41.7% (10/24) (Figure 2). The cure rate differed significantly depending on whether the patient was infected with a strain carrying G248T (S83I) in parC and WT gyrA or G248T (S83I) in parC plus a confirmed gyrA mutation (P = 0.007). The overall cure rate was similar in patients with and without HIV infection (85.7%, 60/70% and 88.9%, 96/108, respectively). Statistical analysis revealed that the clinical effectiveness was not associated with the HIV status of the participants (P = 0.515) (Table S2).

Table 2.

Cure rate of M. genitalium infections according to the presence of antimicrobial-resistance mutations

| Gene | Mutation | Amino acid change | Proportion with the mutation, % (proportion) |

Proportion with combined gyrA or parC mutations, % (proportion) | Cure rate, proportion (%) [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ParC | GyrA mutation detected | ||||

| G248T | S83I | 71.4 (90/126) | 30.0 (24/80) | 71/90 (78.9) [69.0–86.8] | |

| T249A | S83R | 2.4 (3/126) | 0 (0/2) | 3/3 (100) [29.2–100] | |

| G248A | S83N | 0.79 (1/126) | 0 (0/1) | 1/1 (100) [2.5–100] | |

| G259A | D87N | 2.4 (3/126) | 0 (0/3) | 3/3 (100) [29.2–100] | |

| WTa | WTa | 23.0 (29/126) | 3.8 (1/26) | 29/29 (100) [88.1–100] | |

| NDb | NDb | 28.6 (2/7) | 50/54 (92.6) [82.1–97.9] | ||

| GyrA | ParC mutation detected | ||||

| G285T | M95I | 15.1 (18/119) | 94.1 (16/17) | 11/18 (61.1) [35.7–82.7] | |

| G277T | G93C | 2.5 (3/119) | 100 (3/3) | 0/3 (0) [0–70.8] | |

| G295A | D99N | 2.5 (3/119) | 100 (2/2) | 2/3 (66.7) [9.4–99.2] | |

| G295T | D99Y | 0.84 (1/119) | 100 (1/1) | 0/1 (0) [0–97.5] | |

| A296G | D99G | 0.84 (1/119) | 100 (2/2) | 0/1 (0) [0–97.5] | |

| G285C & G295A | M95I & D99N | 0.84 (1/119) | 100 (1/1) | 0/1 (0) [0–97.5] | |

| WT | WT | 77.3 (92/119) | 71.3 (62/87) | 88/92 (95.7) [89.2–98.8] | |

| NDb | NDb | 61.9 (13/21) | 57/61 (93.4) [84.1–98.2] | ||

| ParC·gyrA | |||||

| WT·WT | WT·WT | 29/2 (100) [88.1–100] | |||

| G248T·WT | S83I·WT | 52/56 (92.9) [82.7–98.0] | |||

| G248T·Mc | S83I·M | 10/24 (41.7) [22.1–63.4] | |||

| G248T·G285T | S83I·M95I | 10/16 (62.5) [35.4–84.8] | |||

| Total (all cases) | 158/180 (87.8) [82.1–92.2] |

ND, not detected.

WT parC included three cases of the mutation G244A (D82N).

ND included four cases of no testing. Four cases with no testing were treated successfully.

M indicates all mutations in gyrA, including G285T, G277T, G295A, G295T and A296G.

Figure 2.

Cure rates for (a) patients infected with strains carrying G248T (S83I) in parC and a confirmed mutation in gyrA and (b) rectal and urogenital M. genitalium infection.

The cure rate with the PCR-based Invader kit was 87.8% (65/74), whereas that with the Aptima assay was 86.8% (93/106). The difference in the cure rates measured with the two kits was not significant (P = 0.765). Among the participants evaluated using the Aptima assay, the difference in the cure rate between those with TOC ≤ 21 days (85.7%, 48/56) and TOC > 21 days (90%, 45/50) was not significant (P = 0.502). Among participants evaluated using the Invader kit, the difference in the cure rate between those with TOC ≤ 21 days (89.2%, 33/37) and TOC > 21 days (90%, 32/37) was not significant (P = 0.722).

Patients with treatment failure and de novo quinolone resistance

Twenty-two patients were not cured during the study period (Table 3). Their median age was 33.5 (range, 24–49) years. The median time to TOC was 21 (range, 10–77) days. Pre- and post-treatment samples from 12, 11 and 15 patients were tested for parC, gyrA and 23S-rRNA, respectively. All parC mutant-harbouring strains carried the G248T (S83I) mutation, and no difference was detected between pre- and post-treatment samples. In patients infected with the strain harbouring WT gyrA, the strain remained unchanged in three patients after treatment, and G295A (D99N) changed to WT in one out of eight patients with a gyrA mutation. In patients infected with strains carrying 23S rRNA mutations, 12 patients showed no change and 3 patients showed a change in the type of mutation. None of the patients had strains with a new QRM after sitafloxacin monotherapy. Among 10 patients with samples available for MG309 analysis, 9 had a consistent number of STRs of MG309 in the pre- and post-treatment samples. However, one patient had a different number of STRs in the pre- and post-treatment samples, and the STR sequence chromatograms of MG309 in the pre-treatment samples were clear.

Table 3.

Cases of M. genitalium treatment failure and antimicrobial-resistance profiles in participants before and after treatment with sitafloxacin

| ID | Age (years) | HIV positive? | Time to TOC (days) | Site | Before treatment | After treatment | MG309 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| parC | gyrA | 23S rRNA | parC | gyrA | 23S rRNA | ||||||

| 1 | 29 | No | 24 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G277T (G93C) | A2071G | G248T (S83I) | G277T (G93C) | A2071G | Concordant |

| 2 | 27 | Yes | 26 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G277T (G93C) | A2071G | G248T (S83I) | G277T (G93C) | A2071T | Concordant |

| 3 | 34 | Yes | 21 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | ND |

| 4 | 33 | Yes | 30 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2072G | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2072G | Concordant |

| 5 | 47 | Yes | 13 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I), G295A (D99N) | A2072G | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 6 | 29 | No | 48 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | ND | A2071T | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2071T | Concordant |

| 7 | 27 | No | 21 | Rectal | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 8 | 32 | No | 21 | Urine | ND | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | ND |

| 9 | 24 | No | 21 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2072G | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2072G | Concordant |

| 10 | 37 | No | 10 | Urine | G248T(S83I) | G295A (D99N) | A2071T | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2071T | Concordant |

| 11 | 46 | Yes | 21 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2071T | G248T (S83I) | ND | A2072G | ND |

| 12 | 42 | No | 21 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | Concordant |

| 13 | 26 | Yes | 23 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | ND | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | Concordant |

| 14 | 36 | Yes | 21 | Rectal | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 15 | 40 | Yes | 23 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | ND | ND | A2071T | ND |

| 16 | 47 | No | 21 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | A296G (D99G) | A2072G | G248T (S83I) | A296G (D99G) | A2072G | Discordant |

| 17 | 30 | No | 74 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | WT | A2071T | ND | WT | A2071T | ND |

| 18 | 40 | No | 19 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G295T (D99T) | A2071T | G248T (S83I) | ND | A2071T | Concordant |

| 19 | 27 | Yes | 21 | Rectal | ND | ND | ND | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | ND |

| 20 | 30 | No | 66 | Urine | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | A2072G | NA | NA | NA | ND |

| 21 | 49 | Yes | 77 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G285C (M95I) | WT | NA | NA | NA | ND |

| 22 | 38 | No | 31 | Rectal | G248T (S83I) | G277T (G93C) | A2071T | ND | ND | A2071T | ND |

NA, not applicable; ND, not detected.

The changes observed between pre-treatment and post-treatment results are highlighted in bold.

Bacterial load

M. genitalium load before treatment was measured in 56 samples (48 rectal and 8 urine samples). Before treatment, the bacterial load did not differ significantly according to the sample type (3.25 log10 per swab in rectal samples and 3.55 log10 per 0.5 mL in urine samples; P = 0.529) (Figure S1). In patients with rectal infections, the bacterial load did not differ significantly depending on whether the strain was the WT or harboured a parC mutation (3.56 log10 in WT and 3.11 log10 in parC mutations; P = 0.331).

Safety assessment

Overall, 4.0% of participants reported sitafloxacin-related adverse events (Table 4). The most frequent side effects were diarrhoea (1.7%) followed by abdominal bloating (1.1%) and nausea (0.6%). No side effects led to discontinuation of the treatment.

Table 4.

Drug-related side effects

| Total n (%) (N = 174) |

|

|---|---|

| Overall side effects | 7 (4.0) |

| Diarrhoea | 3 (1.7) |

| Abdominal bloating | 2 (1.1) |

| Nausea | 1 (0.6) |

| Drug rash | 1 (0.6) |

| Self-reported adherence <85%a | 0 (0) |

P values of <0.05 indicate statistical significance.

Self-reported adherence was assessed by the proportion of participants who took the tablets during more than 85% of their opportunities.

Discussion

In this study, sitafloxacin monotherapy could cure 87.8% of rectal and urogenital M. genitalium infections, indicating a high efficacy for rectal infections. In addition, sitafloxacin monotherapy cured the infection in 92.2% of participants carrying the strain with the G248T (S83I) mutation in parC and WT gyrA, which is the predominant strain circulating in most countries with less than 6% prevalence of gyrA mutations.6,9,12,14,18,30-42

Sitafloxacin is reportedly more effective than moxifloxacin against a parC strain with G248T (S83I) mutations.18 According to a study from Australia, moxifloxacin-based therapy resulted in a 54.2% (13/24) cure rate of infection with M. genitalium strains harbouring the G248T (S83I) mutation in parC and WT gyrA, and 18.8% cure rate in those infected with strains harbouring G248T (S83I) in parC and any mutations in gyrA.43

In contrast, our study showed a 92.4% cure rate for strains harbouring the G248T (S83I) mutation in parC and WT gyrA, and a 41.4% cure rate for those with the G248T (S83I) mutation in parC combined with any mutation in gyrA. Although the two therapies were not compared under identical conditions, the results suggest that the cure rate for both resistant strains is likely to be higher with sitafloxacin than with moxifloxacin. Additionally, the study revealed that patients infected with strains with combined mutations in both parC and gyrA were more likely to experience treatment failure with sitafloxacin than those infected with strains with both WT parC and gyrA.

Our results showed no significant difference in the cure rates of patients infected with strains harbouring G248T (S83I) and those with WT parC combined with WT gyrA, suggesting that sitafloxacin monotherapy is effective for treating the majority of rectal and urogenital M. genitalium infections in settings with a low prevalence of gyrA mutations. A previous study suggested a new approach for treating M. genitalium infections based on G248T (S83I) or S83 WT; the authors applied moxifloxacin plus routine TOC or other treatment methods plus symptom-based TOC.44 Routine TOC might not be necessary with sitafloxacin therapy because of the cure rate of more than 90% in infections with strains harbouring G248T (S83I) mutations combined with WT gyrA. However, the presence of both parC and gyrA mutations increases the risk of sitafloxacin failure, as previously described;17 therefore, gyrA mutations are more important in patients with sitafloxacin-resistant infections. The prevalence of gyrA mutation is generally less than 6% in European countries, the USA, South Africa, Singapore and some regions of China and Japan;6,9,12,14,18,30-42 however, it has been reported to be as high as 12.4% in China10% and 25.0% in Japan.8 Routine screening for gyrA mutations is not typically considered necessary, except in high-prevalence countries such as China and Japan. Nevertheless, given the potential for the prevalence of gyrA mutations to increase and spread globally as the use of fluoroquinolones increases, maintaining a focus on antimicrobial stewardship is crucial.

In general, gyrA mutations are associated with parC mutations, and it is probable that parC mutations develop before gyrA mutations.18,43 Only one of the 108 M. genitalium isolates (<1%) harboured a combination of WT parC and gyrA mutations. In settings where the prevalence of parC mutations has increased, monitoring of gyrA mutations should also be considered. Additionally, compared with moxifloxacin, the efficient selection of the gyrA mutation by sitafloxacin could be another factor favouring the development of gyrA mutations, especially considering the high prevalence of M. genitalium strains harbouring gyrA mutations in the countries where sitafloxacin is used.

A previous study suggested that azithromycin was less effective than moxifloxacin for treating rectal infections, suggesting that effectiveness of azithromycin for treating M. genitalium infections varies according to the anatomical site, as with C. trachomatis infections.3,45 As both M. genitalium and C. trachomatis are intracellular bacteria, the same mechanisms that decrease inflammatory response in the rectum might lead to reduced delivery of the drug to the rectal site relative to the genital site.45-47 This study showed that rectal infections and urogenital infections could be successfully treated with sitafloxacin; there was no significant difference in the baseline bacterial load between patients with rectal infection and those with urogenital infection.

We did not detect any new development of QRM after sitafloxacin treatment. One patient showed a change to WT in gyrA. This could be attributable to either reinfection or the patient having a mixed infection with more than one M. genitalium strain.48 The patient reported no sexual intercourse during the post-treatment period to TOC, and TOC was performed at 10 days, which was before the recommended interval.16 Therefore, reinfection was unlikely. Mixed infections were reportedly detected in 6.4% of M. genitalium-positive samples in Australia.48 Regarding the results of MG309, nine patients had a consistent number of STRs of MG309 in the pre- and post-treatment samples, suggesting treatment failure. However, one patient had a different number of STRs in the pre- and post-treatment samples, suggesting a mixed or recurrent infection. There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, considering that this patient reported no sexual intercourse prior to the TOC, a mixed infection is a potential explanation. However, the sequence analysis in this case displayed clear chromatogram peaks, raising doubts about the veracity of the patient’s report of no sexual intercourse, and suggesting a new infection. Additionally, the time interval between the initial and second sample collection was 47 days. Previous studies have confirmed the stability of ATG STR of MG309 for up to 5 weeks.49 According to a study that examined another ATG STR region used for genotyping Mycoplasma pneumoniae, changes were observed within 4 weeks.50 Therefore, it is also possible that a change in the number of STRs over time caused this inconsistency.

This study has several limitations. First, the study population comprised only MSM who were likely to have a higher rate of resistance-associated mutations. In other populations, such as women, a higher cure rate might be expected. Second, the study involved both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Most participants were asymptomatic; therefore, the possibility of a lower bacterial load in asymptomatic patients leading to a higher success rate should be considered. Moreover, in other STIs, such as N. gonorrhoeae infection, the bacterial load is higher in symptomatic rectal infections than in asymptomatic rectal infections.51 Differences in bacterial load have been observed between patients infected with WT and MRM-harbouring M. genitalium, but the presence of parC mutations does not appear to affect the bacterial load.22 Current guidelines do not recommend screening asymptomatic individuals; therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution.16,17

In conclusion, sitafloxacin monotherapy was highly effective for treating rectal and urogenital M. genitalium infections with or without parC mutations, whereas it had limited effectiveness in treating infections caused by M. genitalium strains harbouring gyrA mutations. Sitafloxacin is a good treatment option in settings with a high prevalence of parC mutations and low prevalence of gyrA mutations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Teruya Katsuji, Kunihisa Tsukada and Junko Tanuma for data collection and Yoshimi Deguchi and Mikiko Ogata, the study coordinators, for their assistance in conducting this study.

Contributor Information

Naokatsu Ando, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Daisuke Mizushima, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Misao Takano, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Morika Mitobe, Department of Microbiology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan.

Kai Kobayashi, Department of Microbiology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan.

Hiroaki Kubota, Department of Microbiology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan.

Hirofumi Miyake, Department of Microbiology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan.

Jun Suzuki, Department of Microbiology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan.

Kenji Sadamasu, Department of Microbiology, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Public Health, Tokyo, Japan.

Takahiro Aoki, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Koji Watanabe, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Haruka Uemura, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Yasuaki Yanagawa, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Hiroyuki Gatanaga, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Shinichi Oka, AIDS Clinical Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (grant numbers 19A1002, 20A1020).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Author contributions

N.A. and D.M. conceived and designed the study. N.A., D.M., T.A., K.W., H.U. and Y.Y. contributed to data collection and curation. N.A., D.M. and M.T. were in charge of data curation, and accessed and verified all data. M.M., K.K., H.M., H.K. and J.S. were responsible for laboratory analysis. H.G. and S.O. supervised the study. N.A. wrote the original draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved this manuscript. All authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Data statement

The data used in this study will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Supplementary data

Figure S1 and Tables S1 and S2 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online.

References

- 1. Horner PJ, Martin DH. Mycoplasma genitalium infection in men. J Infect Dis 2017; 216 Suppl 2: S396–405. 10.1093/infdis/jix145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24: 498–514. 10.1128/CMR.00006-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ong JJ, Aung E, Read TRH et al. Clinical characteristics of anorectal Mycoplasma genitalium infection and microbial cure in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2018; 45: 522–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Read TRH, Murray GL, Danielewski JA et al. Symptoms, sites, and significance of Mycoplasma genitalium in men who have sex with men. Emerg Infect Dis 2019; 25: 719–27. 10.3201/eid2504.181258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Machalek DA, Tao Y, Shilling H et al. Prevalence of mutations associated with resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones in Mycoplasma genitalium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20: 1302–14. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30154-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sweeney EL, Trembizki E, Bletchly C et al. Levels of Mycoplasma genitalium antimicrobial resistance differ by both region and gender in the State of Queensland, Australia: implications for treatment guidelines. J Clin Microbiol 2019; 57: e01555-18. 10.1128/JCM.01555-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vesty A, McAuliffe G, Roberts S et al. Mycoplasma genitalium antimicrobial resistance in community and sexual health clinic patients, Auckland, New Zealand. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26: 332–5. 10.3201/eid2602.190533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ando N, Mizushima D, Takano M et al. High prevalence of circulating dual-class resistant Mycoplasma genitalium in asymptomatic MSM in Tokyo, Japan. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2021; 3: dlab091. 10.1093/jacamr/dlab091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ke W, Li D, Tso LS et al. Macrolide and fluoroquinolone associated mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium in a retrospective study of male and female patients seeking care at a STI Clinic in Guangzhou, China, 2016–2018. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 950. 10.1186/s12879-020-05659-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Y, Su X, Le W et al. Mycoplasma genitalium in symptomatic male urethritis: macrolide use is associated with increased resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70: 805–10. 10.1093/cid/ciz294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jensen JS, Bradshaw CS, Tabrizi SN et al. Azithromycin treatment failure in Mycoplasma genitalium-positive patients with nongonococcal urethritis is associated with induced macrolide resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 47: 1546–53. 10.1086/593188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murray GL, Bradshaw CS, Bissessor M et al. Increasing macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium. Emerg Infect Dis 2017; 23: 809–12. 10.3201/eid2305.161745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Couldwell DL, Tagg KA, Jeoffreys NJ et al. Failure of moxifloxacin treatment in Mycoplasma genitalium infections due to macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance. Int J STD AIDS 2013; 24: 822–8. 10.1177/0956462413502008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamasuna R, Le PT, Kutsuna S et al. Mutations in parC and gyrA of moxifloxacin-resistant and susceptible Mycoplasma genitalium strains. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0198355. 10.1371/journal.pone.0198355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hamasuna R, Hanzawa H, Moritomo A et al. Analysis of fluoroquinolone-resistance using MIC determination and homology modelling of parC of contemporary Mycoplasma genitalium strains. J Infect Chemother 2022; 28: 377–83. 10.1016/j.jiac.2021.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep 2021; 70: 1–187. 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M et al. 2021. European guideline on the management of Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2022; 36: 641–50. 10.1111/jdv.17972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murray GL, Bodiyabadu K, Danielewski J et al. Moxifloxacin and sitafloxacin treatment failure in Mycoplasma genitalium infection: association with parC mutation G248T (S83I) and concurrent gyrA mutations. J Infect Dis 2020; 221: 1017–24. 10.1093/infdis/jiz550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Y, Zhu D, Peng Y et al. A randomized, controlled, multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral sitafloxacin versus moxifloxacin in adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Curr Med Res Opin 2021; 37: 693–701. 10.1080/03007995.2021.1885362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen CK, Cheng IL, Lai CC. Efficacy and safety of sitafloxacin in the treatment of acute bacterial infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020; 9: 106. 10.3390/antibiotics9030106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chinen T, Sasabuchi Y, Matsui H et al. Association between third-generation fluoroquinolones and Achilles tendon rupture: a self-controlled case series analysis. Ann Fam Med 2021; 19: 212–6. 10.1370/afm.2673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Read TR, Fairley CK, Tabrizi SN et al. Azithromycin 1.5 g over 5 days compared to 1 g single dose in urethral Mycoplasma genitalium: impact on treatment outcome and resistance. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64: 250–6. 10.1093/cid/ciw719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Read TRH, Fairley CK, Murray GL et al. Outcomes of resistance-guided sequential treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infections: a prospective evaluation. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68: 554–60. 10.1093/cid/ciy477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Takanashi M, Ito S, Kaneto H et al. Development and clinical application of an InvaderPlus® assay for the detection of genital mycoplasmas. J Infect Chemother 2015; 21: 516–9. 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hamasuna R, Aono H, Kawaguchi K et al. Sensitivity of a transcription-mediated amplification method (Aptima Mycoplasma genitalium assay) to detect M. genitalium in vitro. J Infect Chemother 2021; 27: 573–7. 10.1016/j.jiac.2020.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Unemo M, Salado-Rasmussen K, Hansen M et al. Clinical and analytical evaluation of the new Aptima Mycoplasma genitalium assay, with data on M. genitalium prevalence and antimicrobial resistance in M. genitalium in Denmark, Norway and Sweden in 2016. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24: 533–9. 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salado-Rasmussen K, Tolstrup J, Sedeh FB et al. Clinical importance of superior sensitivity of the Aptima TMA-based assays for Mycoplasma genitalium detection. J Clin Microbiol 2022; 60: e0236921. 10.1128/jcm.02369-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jensen JS, Björnelius E, Dohn B et al. Use of TaqMan 5′ nuclease real-time PCR for quantitative detection of Mycoplasma genitalium DNA in males with and without urethritis who were attendees at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 683–92. 10.1128/JCM.42.2.683-692.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ma L, Martin DH. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the rRNA operon and variable numbers of tandem repeats in the lipoprotein gene among Mycoplasma genitalium strains from clinical specimens. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 4876–8. 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4876-4878.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chua TP, Bodiyabadu K, Machalek DA et al. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium fluoroquinolone-resistance markers, and dual-class-resistance markers, in asymptomatic men who have sex with men. J Med Microbiol 2021; 70: 001429. 10.1099/jmm.0.001429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hart T, Tang WY, Mansoor SAB et al. Mycoplasma genitalium in Singapore is associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection and displays high macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance rates. BMC Infect Dis 2020; 20: 314. 10.1186/s12879-020-05019-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bachmann LH, Kirkcaldy RD, Geisler WM et al. Prevalence of Mycoplasma genitalium infection, antimicrobial resistance mutations, and symptom resolution following treatment of urethritis. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71: e624–32. 10.1093/cid/ciaa293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Muller EE, Mahlangu MP, Lewis DA et al. Macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance-associated mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium in Johannesburg, South Africa, 2007–2014. BMC Infect Dis 2019; 19: 148. 10.1186/s12879-019-3797-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stafford IA, Hummel K, Dunn JJ et al. Retrospective analysis of infection and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Mycoplasma genitalium among pregnant women in the southwestern USA. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e050475. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. De Baetselier I, Kenyon C, Vanden Berghe W et al. An alarming high prevalence of resistance-associated mutations to macrolides and fluoroquinolones in Mycoplasma genitalium in Belgium: results from samples collected between 2015 and 2018. Sex Transm Infect 2021; 97: 297–303. 10.1136/sextrans-2020-054511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tagg KA, Jeoffreys NJ, Couldwell DL et al. Fluoroquinolone and macrolide resistance-associated mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51: 2245–9. 10.1128/JCM.00495-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Anderson T, Coughlan E, Werno A. Mycoplasma genitalium macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance detection and clinical implications in a selected cohort in New Zealand. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55: 3242–8. 10.1128/JCM.01087-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Piñeiro L, Idigoras P, de la Caba I et al. Guided antibiotic therapy for Mycoplasma genitalium infections: analysis of mutations associated with resistance to macrolides and fluoroquinolones. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed) 2019; 37: 394–7. 10.1016/j.eimc.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mahlangu MP, Müller EE, Da Costa Dias B et al. Molecular characterization and detection of macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance determinants in Mycoplasma genitalium in South Africa, 2015 to 2018. Sex Transm Dis 2022; 49: 511–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pitt R, Fifer H, Woodford N et al. Detection of markers predictive of macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium from patients attending sexual health services in England. Sex Transm Infect 2018; 94: 9–13. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fifer H, Merrick R, Pitt R et al. Frequency and correlates of Mycoplasma genitalium antimicrobial resistance mutations and their association with treatment outcomes: findings from a national sentinel surveillance pilot in England. Sex Transm Dis 2021; 48: 951–4. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mulligan V, Lynagh Y, Clarke S et al. Prevalence, macrolide resistance, and fluoroquinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium in men who have sex with men attending an sexually transmitted disease clinic in Dublin, Ireland in 2017–2018. Sex Transm Dis 2019; 46: e35–7. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murray GL, Plummer EL, Bodiyabadu K et al. GyrA mutations in Mycoplasma genitalium and their contribution to moxifloxacin failure: time for the next generation of resistance-guided therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76: 2187–95. 10.1093/cid/ciad057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sweeney EL, Bradshaw CS, Murray GL et al. Individualised treatment of Mycoplasma genitalium infection—incorporation of fluoroquinolone resistance testing into clinical care. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22: e267–70. 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00629-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lau A, Kong FYS, Fairley CK et al. Azithromycin or doxycycline for asymptomatic rectal Chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 2418–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa2031631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Heiligenberg M, Lutter R, Pajkrt D et al. Effect of HIV and Chlamydia infection on rectal inflammation and cytokine concentrations in men who have sex with men. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013; 20: 1517–23. 10.1128/CVI.00763-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hocking JS, Kong FY, Timms P et al. Treatment of rectal Chlamydia infection may be more complicated than we originally thought. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 961–4. 10.1093/jac/dku493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sweeney EL, Lowry K, Bletchly C et al. Mycoplasma genitalium infections can comprise a mixture of both fluoroquinolone-susceptible and fluoroquinolone-resistant strains. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021; 76: 887–92. 10.1093/jac/dkaa542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ma L, Taylor S, Jensen JS et al. Short tandem repeat sequences in the Mycoplasma genitalium genome and their use in a multilocus genotyping system. BMC Microbiol 2008; 8: 130. 10.1186/1471-2180-8-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Spuesens EBM, Brouwer RWW, Mol KHJM et al. Comparison of Mycoplasma pneumoniae genome sequences from strains isolated from symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Front Microbiol 2016; 7: 1701. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bissessor M, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK et al. Differing Neisseria gonorrhoeae bacterial loads in the pharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men: implications for gonococcal detection, transmission, and control. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49: 4304–6. 10.1128/JCM.05341-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.