Abstract

The granulosa cells play an important role in the fate of follicular development or atresia in poultry. Fibroblast growth factor 12 (FGF12) is downregulated in atretic follicles and may be involved in regulating granulosa cell survival in previous studies, but its molecular mechanism remains unclear. In this study, FGF12 overexpression and knockdown models of goose granulosa cells were constructed to investigate its function. The downstream expression of the cell cycle pathway was analyzed by qPCR. Granulosa cell proliferative activity and apoptosis were detected by CCK8 and TUNEL. Protein phosphorylation levels of ERK and AKT were measured using Western blotting to analyze the key pathway of FGF12 regulation of granulosa cell proliferation. ERK protein phosphorylation inhibitor was added for further verification. After overexpression of FGF12, cell proliferation activity was increased, the expressions of cell cycle pathway genes CCND1, CCNA2, MAD2, and CHK1 were upregulated, the apoptosis of granulosa cell was decreased, and Caspase 3 gene and protein expression were downregulated. After the knockdown of FGF12, cell proliferation activity decreased, the expression of downstream genes in the cell cycle pathway was downregulated, the apoptosis of granulosa cells was increased, and the Bcl-2 gene and protein were downregulated. Overexpression of FGF12 promoted the synthesis of P4 and upregulates the expression of the STAR gene. Overexpression of FGF12 promoted ERK protein phosphorylation but did not affect AKT phosphorylation. The addition of ERK phosphorylation inhibitors resulted in the elimination of the increase in cell proliferative activity caused by FGF12 overexpression. In conclusion, FGF12 could promote proliferation and inhibit apoptosis of goose granulosa cells by increasing ERK phosphorylation.

Key words: goose, granulosa cell, FGF12, cell cycle, hormone

INTRODUCTION

Egg production in poultry is the process of follicle maturation to ovulation. In birds, only about 5% of the follicles mature and ovulate, while the remaining 95% develop atresia to varying degrees (Tilly, 2001). Atretic follicles do not develop normally, affecting egg production. The development of poultry follicles is regulated by a variety of factors. Negative feedback regulation of reproductive hormones composed of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and ovary plays an important role in follicle maturation to ovulation. In addition, growth factors and sterol hormones secreted by granulosa cells and membrane cells affect follicle development in the form of autocrine and paracrine (Johnson and Lee, 2016). Follicles are composed of the connective tissue layer, membrane cell layer, granulosa cell layer, and perivitelline layer in poultry. Among these cell layers, the survival of the granulosa cell layer is considered to be the key to follicular development or atresia (Matsuda et al., 2012).

Goose meat is a high-quality meat product, lean meat rate is high, rich in all kinds of flavor amino acids, but its reproduction ability is low. In previous studies, we found that there was a large number of atresia in the ovarian follicles of geese, and the FGF12 was low expressed in the atresia follicles, and its low expression may lead to the downregulation of cell cycle pathway genes (Yang et al., 2023a). FGF12 is a member of the fibroblast growth factor family (FGFs), and FGFs are mitogens that play important regulatory roles in cell division, differentiation, and angiogenesis in most tissues and organs (Phan et al., 2021). FGFs were classified as typical FGFs (FGF1-10, FGF16-18, FGF20, FGF22), endocrine FGFs (FGF19, FGF21, FGF23), and intracellular FGFs (FGF11-14) according to the way in which it functions (Ornitz and Itoh, 2015). Multiple members of the FGFs family may regulate follicular development and steroid synthesis during follicular development through autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine (Lin et al., 2019a). Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) can promote bovine granulosa cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner under unanchored culture conditions in vitro (Lavranos et al., 1994). The bFGF can promote small white follicle growth, yolk deposition, and angiogenesis during chicken follicle development via the FGFR-AKT pathway (Lin et al., 2019a). FGF10 can inhibit the growth of bovine follicles, downregulate the expression of CYP19A1 in the granulosa layer, and reduce the production of E2 by 50 times in cultured bovine follicles (Gasperin et al., 2012; Portela et al., 2015). FGF18 can increase the apoptosis rate of bovine follicular membrane granulosa cells, decrease the expressions of antiapoptotic proteins GADD45B and MDM2 in granulosa cells, and increase the expression of proapoptotic protein BBC3 (Portela et al., 2015). Endocrine type FGF21 can promote estradiol secretion and proliferation of porcine ovarian granulosa cells through PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (Hu et al., 2022).

The FGF family homologous growth factors (FHFs, FGF11 = FHF3, FGF12 = FHF1, FGF13 = FHF2, FGF14 = FHF4) are intracellular signal molecules due to the lack of extracellular signal peptide sequences (Goldfarb, 2005). FHFs cannot be secreted outside the cell, but they are effective intracellular signaling proteins that affect cellular processes just like other types of FGF (Ornitz and Itoh, 2015). FHFs are expressed primarily in the nervous system, but also cardiomyocytes, fibroblasts, bone cells, and endothelial cells, and its deficiency has been linked to diseases including cancer, arrhythmia, and the nervous system (Wei et al., 2011; Okada et al., 2013; Otani et al., 2018). As a member of the FHF family, FGF12 can be used as a regulator of Na+ voltage-gated channels in cell membranes, regulate neuronal contact response through membrane voltage change to induce seizures in nerve cells, negatively regulate vascular smooth muscle cell remodeling in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension, serve as a serum biomarker for early diagnosis of gastric cancer in patients with gastric cancer, and promote hair development in mice (Effraim et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2019; Yeo et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2021; Woo et al., 2022).

The FGF12 plays a role in a variety of cells, and we also detected the downregulation of FGF12 in atretic follicles. However, its role in follicular development remains unknown. Therefore, this study further explored the role of FGF12 in follicle development at the cellular level.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

All animal experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of Anhui Agricultural University with the assurance number SYDW-P20210823021.

Animal Sample

All the animals in the experiment were taken from Wanxi white goose breeding farm (Anhui Xianglin Agricultural Technology Development Co., Ltd., Huoqiu, China). The geese were raised on the ground with free access to feed and water. Healthy female geese in the first peak laying stage (around 330 d of age) were selected, and subjected for cervical dislocation for small yellow follicle isolation. The granulosa cells of goose small yellow follicles were isolated, digested and cultured within 6 h after slaughter. The identification of normal and atresia follicle refers to Yang et al. (2023a).

Recombinant Plasmid Construction

The plasmid of FGF12 overexpression and knockdown was constructed by Hefei Yuanen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The coding sequence of FGF12 was synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China), according to transcript variant X1, mRNA, Anas platyrhynchos (XM_027463962.2). The synthesized cDNA of FGF12 was cloned into the Nhel and Agel polyclonal site of PCDNA3.1-EGFP plasmid to generate the pEGFP-FGF12 overexpressed vector (OE-FGF12). The PCDNA3.1-EGFP vector without cDNA insertion was set as the negative control (NC).

Two sequences of short hairpin RNAs (shRNA) were designed to knockdown the expression of FGF12. The 2 shRNAs (shRNA1: 5′-ACCGGGGTTCCTGGGACTCAATAAAGCTCGAGCTTTATTGAGTCCCAGGAACCTTTTTGAATTC-3′, shRNA2: 5′-ACCGGGCACCCAGATGGTACAATTGACTCGAGTCAATTGTACCATCTGGGTGCTTTTTGAATTC-3′) were cloned by seamless cloning of EcoRI, pLKO.1-EGFP-puro, named shRNA-1 and shRNA-2. The shRNAs were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China).

The constructed vector was transfected into E. coli TOP10 for amplification, and the plasmid was extracted using Endofree Maxi Plasmid kit (DP117, Tiangen, China). All the extracted plasmids were stored at −80°C till further use after being sequenced correctly (Additional file S1, S2, and S3). The OE-FGF12 plasmid sequencing primers were pEGFP-N-3′ and pEGFP-N-5′, and the shRNAs plasmid sequencing primer was PHB2-seqR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers used for the qRT-PCR of each gene.

| Genes | Genes ID | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEGFP | CGTCGCCGTCCAGCTCGACCAG | TGGGAGGTCTATATAAGCAGAG | ||

| PHB2-seqR | TGGGCAGT TTACCGTAAATACT | |||

| CHK1 | 106040556 | GCTGGTGAAGAGGATGACGC | CTCCTGTCCGTGGTGGAGAT | 144 |

| MCM3 | 106038116 | CCGCGACCAAGAAGACCATC | CCTTGTAGACCGAGAGGCCA | 138 |

| CCNA2 | 106042451 | GCTGAGCTTGCACCTCTTCA | CCTCCCCAGTGAGAAGGATGT | 134 |

| MAD2 | 106038609 | TTCACCCGCGTCCAGAAGTA | GCACTTGCAGAGCCACTCTT | 111 |

| CDK1 | 106031512 | ATGGCCTGATGTGGAGTCCC | AAAGCAGATCAAGCCCATCTTCAT | 113 |

| CCND1 | 106044779 | CGAGCCTGCCAAGAACAGAT | GTGTGCAGGAAAGGTCTGCT | 118 |

| FGF12 | 101798106 | AGCTCGGATGTTTTCACACC | GCGTCCTTGTTTTTCTCCAA | 258 |

Granulosa Cell Culture and Transfection

Collected follicles were washed with PBS (1% Penicillin-Streptomycin) to remove blood, and then peripheral connective tissue was peeled off. Follicle content was released by puncture the membrane and gently cleaned by PBS (1% Penicillin-Streptomycin). The granulosa cell layer was removed by gently shaking and the rest was the theca layer. The isolation and culture of follicular granulosa cells of geese were performed according to Du et al. (2022). The isolated granular cells were cultured in 6-well plates for plasmid transfection. Plasmid transfection was performed using the ExFect Transfection Reagent kit (T101-01, Vazyme, China) according to Du et al. (2022). The expression of gene mRNA and protein, as well as cell proliferation and apoptosis were analyzed 36 h after transfection. The expression level of FGF12 was determined by qRT-PCR. The ERK phosphorylation inhibitor ISRIB (MB4567-1, meilunbio, Dalian, China) was dissolved in DMSO. The concentration of the ISRIB in the culture medium was maintained at 200 nM (Mo et al., 2019).

Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis Assay

Cell proliferation and apoptosis were detected using Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) Kit (SK2060-100T, Coolaber, Beijing, China) and TdT-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) Apoptosis Detection Kit (Orange Fluorescence, California, CA), respectively, with specific operations according to Wei et al. (2023).

RNA Extraction, cDNA Synthesis, and qRT-PCR

Twelve normal and atretic follicles, respectively, isolated from 12 geese were selected for mRNA quantification. Total RNA was extracted from theca and granular layer of small yellow follicles and cultured granulosa cells by Trizol (Shanghai Yisheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd., China). The cDNA synthesis was performed using Hifair II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (YEASEN, Shanghai, China). The qRT-PCR was performed using the Trans Start Green qPCR SuperMix Kit (TAKARA, Dalian, China) on the ABI 7500 system (Thermo, Massachusetts, MA) according to Yang et al. (2023a). The primers were designed using the online platform Primer 3.0 (https: //bio info.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/, Table 1).

Western Blot Analysis

Total protein extraction from granulosa cells was performed using Total Protein Extraction Kits (MA0171, Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China). After the granular cells were digested with trypsin for 5 min, the cell suspension was centrifuged for 10 min (3,000 rpm/min) to collect the precipitates. Cell lysis solution (10 μL/mL PMSF, phosphorylase inhibitor and protease inhibitor) was added to the precipitates for 15 min, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rpm. The supernatant was collected as total protein. The total protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (YEASEN, Shanghai, China). Gel electrophoresis (12% PAGE) and transmembrane was conducted according to Yang et al. (2023a). Rabbit anti-Caspase-3 (YT0656, 1:1,000, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX), rabbit anti-CCND1 (YT1172, 1:1,000, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX), rabbit anti-β-Actin (1:1,000, ABclonal, Wuhan, China), mouse anti-BCL2 (YM3041, 1:1,000, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX), mouse anti-ERK (YT1625, 1:1,000, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX), mouse anti-pERK (YP0101, 1:1,000, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX), mouse anti-AKT (YT0175, 1:1,000, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX), and rat anti-pAKT (YP0007, 1:1,000, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX) were selected as primary antibodies. Goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:30,000, BIOMIKY, Shanghai, China) and goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, PS001, ImmunoWay, Texas, TX) labeled with HRP were selected as secondary antibodies. Protein blots were visualized using chemiluminescence imaging system 398 (UVitec, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and quantified using Image J software (National Institutes of Health).

Hormone Assay

After being transfected with overexpressed and knocked down plasmids, granulosa cells were cultured for 36 h, and the culture medium was collected for determination of hormones concentration. Concentrations of E2 and P4 were determined by using ELISA kit (KS21759, KS21781, Keshun Tech, Shanghai, China) according to Yang et al. (2023a).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using Prism 8.0 GraphPad Software. Differences of gene expression between cell layer (theca and granular layer) and follicle stasis (atresia and normal follicle) were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA. Protein and gene expression, cell proliferation and apoptosis, and hormone concentration in cultured granulosa cell were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Expression of FGF12 and Cell Cycle Pathway Genes in the Membrane Layer and Granular Layer

Because the previous transcriptome sequencing was performed at the whole follicle level, we first detected the expression of FGF12 gene and cell cycle pathway-related genes in the membrane cell layer and granulosa cell layer. In both normal and atretic follicles, the mRNA expression of FGF12 was higher in the granulosa layer than in the membrane layer (P < 0.05, Figure 1A), and the mRNA expression level of FGF12 in the normal follicular granulosa layer was higher than that in atretic follicular granulosa layer (P < 0.05, Figure 1A). The expression levels of cell cycle pathway-related genes CHK1, CCND1, CCNA2, and MCM3 in the membrane layer and granulosa layer of atretic follicles were lower than those in normal follicles (P < 0.05, Figure 1B–E). This indicates that FGF12 is mainly expressed in the granulosa cell layer, and the expression of genes related to cell proliferation in the cell cycle pathway was downregulated in the membrane and granular cell layers of atretic follicles.

Figure 1.

qRT-PCR analysis of genes in the membrane layer and granular layer. (A) The relative expression of FGF12. (B) The relative expression of CHK1. (C) The relative expression of CCND1. (D) The relative expression of CCNA2. (E) The relative expression of MCM3. NF was normal follicle, AF was atretic follicle, TC was theca layer, GC was granulosa layer. P1 represents the P value of gene expression between membrane layer and granular layer, P2 represents the P value of gene expression in normal and atretic follicles, and P3 represents the P value of the interaction effect of the 2 factors.

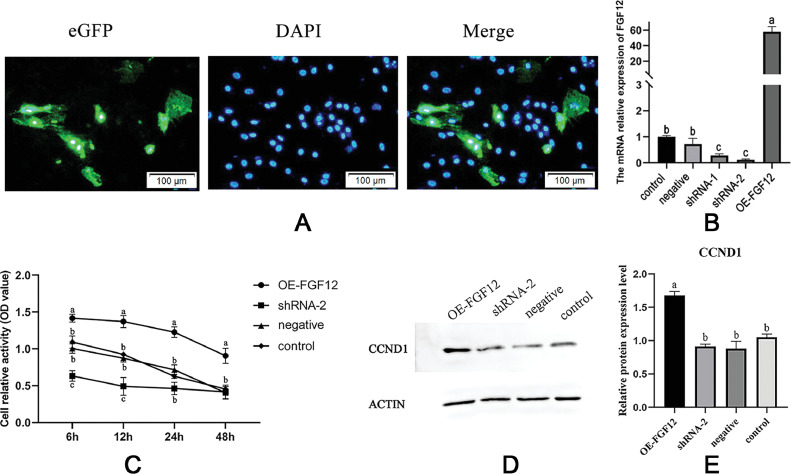

The Overexpression of FGF12 Promoted Granulosa Cell Proliferation in Goose

To investigate the function of FGF12 in granulosa cells, we constructed FGF12 overexpression and knockdown cell models. The constructed plasmid was transfected into goose granulosa cells, and the cells successfully transferred showed green fluorescence (Figure 2A). The overexpression and knockdown efficiency of FGF12 were verified by qPCR. The mRNA expression level of FGF12 in the overexpression group was significantly higher than that in the negative control and the blank control, and that in knockdown was significantly lower than that in the blank control and negative control (P < 0.05, Figure 2B). This indicated that the cell model of FGF12 overexpression and interference was successfully constructed. Both shRNA1 and shRNA2 could effectively reduce the expression level of FGF12 mRNA, but shRNA2 had higher knockdown efficiency. Therefore, shRNA2 was selected as the knockdown group in subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

FGF12 promotes granulosa cell proliferation. (A) Granulosa cell plasmid transfection, green is the GFP fluorescence of the plasmid, blue is the nucleus stained by DAPI, merge represents the superposition of 2 pictures. (B) The relative expression of FGF12 mRNA in different groups. (C) The cell proliferation activity measured by CCK8. (D) Western blot of CCND1 protein. (E) Analysis of the relative gray values of the blotting bands. OE-FGF12 represented the overexpression, shRNA-2 represented the interference, negative represented the empty plasmid negative control, and control represented the blank control. Different letters represent significant differences in different groups (P < 0.05).

The CCK8 was used to detect the proliferation activity of granulosa cells after FGF12 overexpression and interference. The cell proliferation activity of OE-FGF12 was significantly higher than that of shRNA2, negative control, and blank control at all time points (P < 0.05). Cell proliferative activity in group shRNA2 was lower than that in negative and blank control at 6 h and 12 h, and the cell activity gradually decreased with time (Figure 2C). The CCND1 gene encodes Cyclin D1, a signature protein of cell proliferative activity, and was significantly higher in OE-FGF12 than in shRNA2, negative control, and blank control group (Figure 2D and E).

FGF12 Upregulates the Expression of Related Genes in the Cell Cycle Pathway

Genes CCND1, CCNA2, MAD2, MCM3, and CHK1 are the downstream of the cell cycle pathway, and their expressions are closely related to cell proliferation and differentiation. Overexpression of FGF12 significantly increased the expression levels of these genes (Figure 3), confirming the interaction between FGF12 and the cell cycle pathway in previous experiments. These results indicated that FGF12 could promote cell proliferation by upregulating the expression of downstream genes in the cell cycle pathway.

Figure 3.

Analysis of gene expression in downstream cell cycle pathway, A to E are the relative expression levels of CCND1, CCNA2, MAD2, MCM3, and CHK1, respectively. OE-FGF12 represented the overexpression, shRNA-2 represented the interference, negative represented the empty plasmid negative control, and control represented the blank control. Different letters represent significant differences in different groups (P < 0.05).

The Overexpression of FGF12 Inhibited Granulosa Cell Apoptosis

The granulosa cells showed a large amount of apoptosis in shRNA2 while showing less apoptosis in OE-FGF12 (Figure 4A). The mRNA and protein expressions of Bcl-2 and Caspase 3 were quantitatively analyzed (Figure 4B, 4C and 4D), in which Bcl-2 was the antiapoptotic marker protein and Caspase 3 was the apoptotic marker protein. The mRNA of the Bcl-2 gene in the knockdown group was significantly lower than that in the overexpression group (P < 0.05). The Bcl-2 protein in the knockdown group was significantly lower than that in overexpression and blank control (P < 0.05). The mRNA and protein expression levels of the Caspase 3 gene were the highest in the knockdown group and almost no expression in the overexpression group (P < 0.05). These results suggest that FGF12 could inhibit granulosa cell apoptosis by upregulating Bcl-2.

Figure 4.

FGF12 inhibited granulosa cell apoptosis. (A) TUNEL staining of granulosa cells in different groups. Apoptotic cells showed red fluorescence. (B) The mRNA relative expression levels of Bcl-2 and Caspase 3. (C) Western blotting of Bcl-2 and Caspase 3. (D) The gray value analysis of protein blotting. Different letters represent significant differences in different groups (P < 0.05).

Effects of FGF12 on Granulosa Cell Hormone Synthesis

Sterol hormones E2 and P4 can be synthesized in granulosa cells, and both play a role in granulosa cell proliferation and follicle development regulation. Therefore, the contents of E2 and P4, as well as the expression of key genes in the synthesis process, were analyzed. The overexpression of FGF12 increased the content of P4 but did not affect the content of E2 (Figure 5A and B). Genes CYP19A1 and CYP17A1 are the key for E2 synthesis, and STAR is the key for P4 synthesis. The overexpression of FGF12 upregulates the expression of the STAR gene, while the interference of FGF12 downregulates the expression of STAR and CYP19A1 genes (Figure 5C and D). This indicates that FGF12 can upregulate STAR to promote P4 synthesis.

Figure 5.

Effect of FGF12 overexpression and knockdown on steroid hormone synthesis in granulosa cells. (A) E2 content in different groups. (B) P4 content in different groups. (C) The relative expression of CYP19A1 mRNA in different groups. (D) The relative expression of STAR mRNA in different groups. (E) The relative expression of CYP17A1 mRNA in different groups.

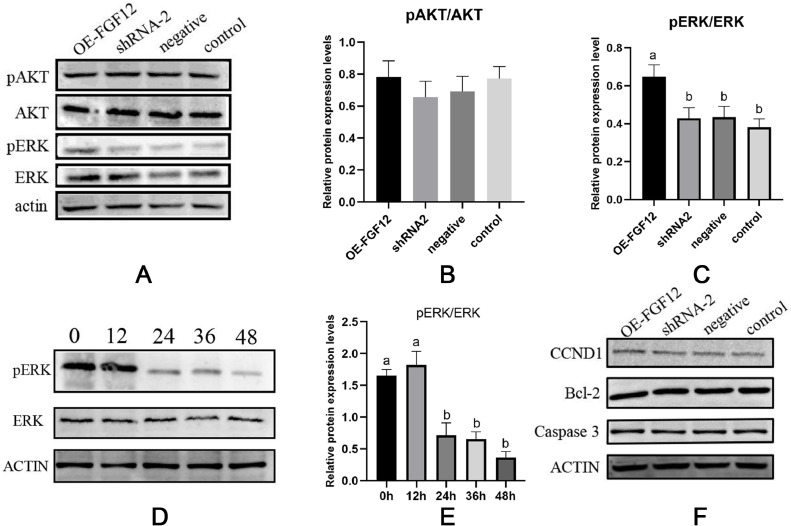

FGF12 Promotes Granulosa Cell Proliferation by Increasing ERK Phosphorylation

Studies have shown that FGF12 may regulate cell processes through ERK or PI3K-AKT (Nakayama et al., 2008; Mo et al., 2019), so we analyzed the phosphorylation levels of AKT and ERK. Overexpression of FGF12 significantly promoted phosphorylation of ERK (P < 0.05) but did not affect phosphorylation of AKT (P > 0.05, Figure 6A and B). To further explore the role of ERK phosphorylation in FGF12 regulation of granulosa cell proliferation, an inhibitor of ERK phosphorylation (ISRIB) was added. The phosphorylation level of ERK was determined at 0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h after the addition of ISRIB. The results showed that the phosphorylation level of ERK decreased significantly at 24 h (Figure 6D and E). Therefore, the treatment time of ISRIB was selected at 24 h for subsequent tests. The expression of CCND1, Bcl-2, and Caspase 3 proteins was no significant difference in FGF12 overexpressed and interfered granulosa cells after adding ISRIB (Figure 6F). This once again suggests that FGF12 promotes granulosa cell proliferation and apoptosis through the ERK pathway.

Figure 6.

FGF12 promotes granulosa cell proliferation through ERK phosphorylation. (A) Western blotting of pAKT, AKT, pERK, and ERK. (B) The gray value analysis of protein pAKT/AKT bands. (C) A gray value analysis of protein pERK/ERK bands. (D) Western blotting of pERK and ERK at 0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h after the addition of the ERK inhibitor ISRIB. (E) The gray value analysis of protein pERK/ERK bands at 0 h, 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, and 48 h after the addition of ERK inhibitor ISRIB. (F) Western blotting of the proteins CCND1, Bcl-2, and Caspase 3 after the addition of the ERK inhibitor ISRIB. OE-FGF12 represented the overexpression, shRNA-2 represented the interference, negative represented the empty plasmid negative control, and control represented the blank control. Different letters represent significant differences (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The membrane layer and granulosa layer cells of follicles can secrete a variety of reproductive hormones and growth factors, and there are receptors for these signaling factors, which are the key structures to promote the development and maturation of follicles (Ghanem and Johnson, 2018). The granulosa cells are thought to be the site of first apoptosis and subsequently induce apoptosis in other cell layers until follicles are completely cleared in apoptotic follicles in mice (Palumbo and Yeh, 1994). However, in this study, the expressions of genes CHK1, CCND1, CCNA2, and MCM3 related to cell proliferation activity in the Cell cycle pathway were downregulated in the membrane and granulosa layer of atretic follicles compared with those in normal follicles, indicating that the decrease in proliferation activity of atretic follicles was present in both the granulosa layer and the membrane layer. This may be due to follicles that can be observed in appearance with atresia are actually in the middle and late stages of atresia (Giebel et al., 1997).

The FGF12 was mainly expressed in the granulosa cell layer. FGF12 is a fibroblast FGF family homologous growth factor (FHF1), which lacks signal peptide in its amino acid sequence and cannot be secreted into the extracellular. Thus, the place where FGF12 acts are in the granulosa cells layer. Overexpression of FGF12 increased the proliferative activity of granulosa cells, while interference decreased the proliferative activity of granulosa cells, indicating that FGF12 may positively regulate the proliferation of granulosa cells. FGF12 knockdown increased apoptosis of granulosa cells, while overexpression decreased apoptosis. The Caspase 3 protein is a marker of apoptosis and is activated during apoptosis and performs cell death procedures (Tammaro et al., 2017). The Bcl-2 protein is an antiapoptotic protein, which can effectively inhibit the occurrence of apoptosis procedures (Flaws et al., 2001). The mRNA and protein expressions of the Caspase 3 gene were upregulated, while those of the Bcl-2 gene was downregulated after FGF12 knockdown. FGF12 may maintain the expression of Bcl-2 in cells and inhibit the occurrence of apoptosis.

The granulosa cells of poultry follicles themselves can synthesize E2 and P4 to regulate the development of follicles. The P4 plays an important role in the development and ovulation of poultry follicles, and the STAR enzyme is essential for the synthesis of P4 (Manna and Stocco, 2005). The content of P4 increased with follicle development in chickens (Yang et al., 2023b). In this study, FGF12 could upregulate the expression of STAR and promote the synthesis of P4 to regulate the proliferation of granulosa cells.

Cell cycle pathway is a key pathway in follicular atresia, and when follicular atresia occurs, the expression of genes related to cell proliferation in cell cycle pathway is downregulated (Yang et al., 2023a). Cyclin D1 is a protein that is encoded by the CCND1 gene and regulates the activity of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). It is an essential protein during the G1 to S phase transition in mitosis and serves as a marker for cell proliferation (Liu et al., 2019b). Overexpression of FGF12 upregulates the expression of Cyclin D1 protein, as well as the expressions of CCND1, CCNA2, MAD2, MCM3, and CHK1 mRNA. These findings suggest that FGF12, despite being a nonsecreted protein, can regulate gene expression in the cell cycle.

It is generally believed that FHFs cannot bind to FGFR and activate the classical FGFR signaling pathway (Ornitz and Itoh, 2015). Instead, FHFs are known to bind specifically with intracellular proteins such as IB2, β-tubulin, and NEM0209 to regulate nerve cell proliferation and differentiation (Schoorlemmer and Goldfarb, 2001; Schoorlemmer and Goldfarb, 2002; Wu et al., 2012). Although FHF cannot be secreted extracellular, extracellular FHF can also play a role. Lin et al. (2019c) demonstrated that FGF13 (FHF2) can be released extracellularly through nonconventional cell breakdown, activating the FGF-FGFR signaling pathways and playing a role similar to classical fibroblast growth factors in promoting cell division (Lin et al., 2019c). Sochacka et al. (2020) further study found that FGF12 (FHF1) can also activate FGF-FGFR classical signaling pathway (Sochacka et al., 2020). Another view is that FHFs do not activate FGFR, but enter cells in the form of endocytosis and thus play a role. In intestinal epithelial cells, FGF12 can function in a manner independent of FGFR by a novel cell-penetrating peptide (Nakayama et al., 2011). FHFs can play an effective role both intracellular and extracellular in the regulation of cellular processes, but the mechanism is not fully understood. In this study, overexpression of FGF12 in granulosa cells can effectively promote proliferation and inhibit apoptosis, and regulate gene expression in the downstream cell cycle pathway like typical members of the FGF family. In radiation-induced human mast cells, overexpression of FGF12 significantly inhibited apoptosis, whereas silencing FGF12 led to increased apoptosis by promoting ERK phosphorylation (Nakayama et al., 2008). Exogenous addition of FGF12 promotes mesenchymal cell regeneration in male rat stem cells by promoting AKT1 phosphorylation (Mo et al., 2019). In this study, overexpression of FGF12 did not affect AKT phosphorylation, but increased ERK phosphorylation. ISRIB is an inhibitor of ERK protein phosphorylation, which can effectively inhibit ERK phosphorylation at a final concentration of 200 nM (Mo et al., 2019). After the addition of ISRIB in FGF12 overexpressed cells, the increased expressions of CCND1, Caspase 3, and Bcl-2 were inhibited, and its effect on promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis of granulosa cells was reversed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by Application of high efficiency rearing technology in antiseason for goose breeding (2018YFD0501505-2) and Science and Technology Program of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2020B01004-2-1).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.102937.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- Du Y., Chen X., Yang H., Sun L., Wei C., Yang W., Zhao Y., Liu Z., Geng Z. Expression of oocyte vitellogenesis receptor was regulated by C/EBPα in developing follicle of Wanxi white goose. Animals (Basel) 2022;12:874. doi: 10.3390/ani12070874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effraim P.R., Huang J., Lampert A., Stamboulian S., Zhao P., Black J.A., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 2 (FGF-13) associates with Nav1.7 in DRG neurons and alters its current properties in an isoform-dependent manner. Neurobiol. Pain. 2019;6 doi: 10.1016/j.ynpai.2019.100029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaws J.A., Hirshfield A.N., Hewitt J.A., Babus J.K., Furth P.A. Effect of bcl-2 on the primordial follicle endowment in the mouse ovary. Biol. Reprod. 2001;64:1153–1159. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.4.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasperin B.G., Ferreira R., Rovani M.T., Santos J.T., Buratini J., Price C.A., Gonçalves P.B. FGF10 inhibits dominant follicle growth and estradiol secretion in vivo in cattle. Reproduction. 2012;143:815–823. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem K., Johnson A.L. Follicle dynamics and granulosa cell differentiation in the turkey hen ovary. Poult. Sci. 2018;97:3755–3761. doi: 10.3382/ps/pey224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebel J., Hegele-Hartung C., Rune G.M. Proliferation and apoptosis in follicles of the marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus) ovary. Ann. Anat. 1997;179:413–419. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(97)80034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors: evolution, structure, and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Xu J., Shi S.J., Zhou X., Wang L., Huang L., Gao L., Pang W., Yang G., Chu G. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) promotes porcine granulosa cell estradiol production and proliferation via PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling. Theriogenology. 2022;194:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.L., Lee J. Granulosa cell responsiveness to follicle stimulating hormone during early growth of hen ovarian follicles. Poult. Sci. 2016;95:108–114. doi: 10.3382/ps/pev318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavranos T.C., Rodgers H.F., Bertoncello I., Rodgers R.J. Anchorage-independent culture of bovine granulosa cells: the effects of basic fibroblast growth factor and dibutyryl cAMP on cell division and differentiation. Exp. Cell. Res. 1994;211:245–251. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Lu P., Zhou M., Wu F., Weng L., Meng K., Yang D., Li S., Jiang C., Tian H. Purification of recombinant human fibroblast growth factor 13 in E. coli and its molecular mechanism of mitogenesis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;103:7017–7027. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-09973-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Ma Y., Qian T., Yao J., Mi Y., Zhang C. Basic fibroblast growth factor promotes prehierarchical follicle growth and yolk deposition in the chicken. Theriogenology. 2019;139:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2019.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Pan B., Yang L., Wang B., Li J. Beta defensin 3 enhances ovarian granulosa cell proliferation and migration via ERK1/2 pathway in vitro. Biol. Reprod. 2019;100:1057–1065. doi: 10.1093/biolre/ioy246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna P.R., Stocco D.M. Regulation of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression: functional and physiological consequences. Curr. Drug. Targets. 2005;5:93–108. doi: 10.2174/1568008053174714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda-Minehata F., Inoue N., Manabe N., Ohkura S. Follicular growth and atresia in mammalian ovaries: regulation by survival and death of granulosa cells. J. Reprod. Dev. 2012;58:44–50. doi: 10.1262/jrd.2011-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo J., Chen X., Ni C., Wu K., Li X., Zhu Q., Ma L., Chen Y., Zhang S., Wang Y., Lian Q., Ge R.S. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factor 1 stimulates Leydig cell regeneration from stem cells in male rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019;23:5618–5631. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama F., Müller K., Hagiwara A., Ridi R., Akashi M., Meineke V. Involvement of intracellular expression of FGF12 in radiation-induced apoptosis in mast cells. J. Radiat. Res. 2008;49:491–501. doi: 10.1269/jrr.08021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama F., Yasuda T., Umeda S., Asada M., Imamura T., Meineke V., Akashi M. Fibroblast growth factor-12 (FGF12) translocation into intestinal epithelial cells is dependent on a novel cell-penetrating peptide domain: involvement of internalization in the in vivo role of exogenous FGF12. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:25823–25834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T., Murata K., Hirose R., Matsuda C., Komatsu T., Ikekita M., Nakawatari M., Nakayama F., Wakatsuki M., Ohno T., Kato S., Imai T., Imamura T. Upregulated expression of FGF13/FHF2 mediates resistance to platinum drugs in cervical cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2899. doi: 10.1038/srep02899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornitz D.M., Itoh N. The fibroblast growth factor signaling pathway. Wiley Dev. Biol. 2015;4:215–266. doi: 10.1002/wdev.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani Y., Ichikawa T., Kurozumi K., Inoue S., Ishida J., Oka T., Shimizu T., Tomita Y., Hattori Y., Uneda A., Matsumoto Y., Michiue H., Date I. Fibroblast growth factor 13 regulates glioma cell invasion and is important for bevacizumab-induced glioma invasion. Oncogene. 2018;37:777–786. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo A., Yeh J. In situ localization of apoptosis in the rat ovary during follicular atresia. Biol. Reprod. 1994;51:888–895. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.5.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan P., Saikia B.B., Sonnaila S., Agrawal S., Alraawi Z., Kumar T.K.S., Iyer S. The saga of endocrine FGFs. Cells. 2021;10:2418. doi: 10.3390/cells10092418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portela V.M., Dirandeh E., Guerrero-Netro H.M., Zamberlam G., Barreta M.H., Goetten A.F., Price C.A. The role of fibroblast growth factor-18 in follicular atresia in cattle. Biol. Reprod. 2015;92:14. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.114.121376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoorlemmer J., Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors are intracellular signaling proteins. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:793–797. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00232-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoorlemmer J., Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors and the islet brain-2 scaffold protein regulate activation of a stress-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:49111–49119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sochacka M., Opalinski L., Szymczyk J., Zimoch M.B., Czyrek A., Krowarsch D., Otlewski J., Zakrzewska M. FHF1 is a bona fide fibroblast growth factor that activates cellular signaling in FGFR-dependent manner. Cell. Commun. Signal. 2020;18:69. doi: 10.1186/s12964-020-00573-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammaro S., Simoniello P., Ristoratore F., Coppola U., Scudiero R., Motta C.M. Expression of Caspase 3 in ovarian follicle cells of the lizard Podarcis sicula. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367:397–404. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q., Li H., Shu L., Wang H., Peng Y., Fang H., Mao X. Effective treatments for FGF12-related early-onset epileptic encephalopathies patients. Brain Dev. 2021;43:851–856. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2021.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilly J.L. Commuting the death sentence: how oocytes strive to survive. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:838–848. doi: 10.1038/35099086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei E.Q., Barnett A.S., Pitt G.S., Hennessey J.A. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors in the heart: a potential locus for cardiac arrhythmias. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2011;21:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C., Chen X., Peng J., Yu S., Chang P., Jin K., Geng Z. BMP4/SMAD8 signaling pathway regulated granular cell proliferation to promote follicle development in Wanxi white goose. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo J., Suh W., Sung J. Hair growth regulation by fibroblast growth factor 12 (FGF12) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:9467. doi: 10.3390/ijms23169467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q.F., Yang L., Li S., Wang Q., Yuan X.B., Gao X., Bao L., Zhang X. Fibroblast growth factor 13 is a microtubule-stabilizing protein regulating neuronal polarization and migration. Cell. 2012;149:1549–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D., Zhang P., Ma J., Xu J., Yang L., Xu W., Que H., Chen M., Xu H. Serum biomarker panels for the diagnosis of gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2019;8:1576–1583. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Chen X., Liu Z., Zhao Y., Chen Y., Geng Z. Integrated transcriptome and proteome revealed that the declined expression of cell cycle-related genes associated with follicular atresia in geese. BMC Genom. 2023;24:24. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-09088-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Ji Y., Yong T., Liu T., Yang S., Guo S., Meng F., Han X., Liang Q., Cao X., Huang L., Du X., Huang A., Kong F., Zeng X., Bu G. Corticosterone stage-dependently inhibits progesterone production presumably via impeding the cAMP-StAR cascade in granulosa cells of chicken preovulatory follicles. Poult. Sci. 2023;102 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2022.102379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo Y., Yi E.S., Kim J.M., Jo E.K., Seo S., Kim R.I., Kim K.L., Sung J.H., Park S.G., Suh W. FGF12 (fibroblast growth factor 12) inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76:1778–1786. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.