Abstract

Background:

Care partners (CP) of people with dementia (PWD) report that decisions about care setting are aided by the support of healthcare providers. However, providers are often underprepared to offer adequate counseling.

Objective:

This qualitative study aimed to identify what support from providers will assist CPs in making decisions related to care setting throughout the dementia journey.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with current CPs of PWD and former CPs of decedents. We utilized the constant comparative method to identify themes regarding preferences around care setting as the PWD progressed from diagnosis to end-of-life.

Results:

Participants were 31 CPs, including 16 current and 15 former CPs. CPs had a mean age of 67 and were primarily white (n=23/31), female (n=21/31), and spouses (n=24/31). Theme 1: Current CPs discussed overwhelming uncertainty pertaining to care setting, expressing “I don’t know when I need to plan on more care,” and a desire to understand “what stage we are at.” Theme 2: Later in the disease, former CPs wanted guidance from healthcare providers on institutional placement (“I sure would’ve loved some help finding better places”) or support to stay in the home (“a doctor had to come to the house”).

Conclusions:

CPs want early, specific guidance from healthcare providers related to transitions between home and long-term care. Early in the disease course, counseling geared toward prognosis and expected disease course helps CPs make plans. Later, caregivers want help identifying locations or institutionalization or finding home care resources.

Keywords: Caregivers, dementia, long-term care, residential facilities, counseling, healthcare provider

INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a major public health problem, affecting an estimated 11% of people aged 65 and older and 11 million people who provide assistance as unpaid care partners (CP).1 Older adults prefer to live and die at home2,3 including for dementia-related care.4 However, as dementia-related care needs escalate throughout the disease, caregivers may consider institutional placement if people with dementia (PWD) are unable to remain at home.1,5 There are high rates of institutionalization, including residential and nursing facilities, among PWD suggesting that millions of families are navigating difficult care setting decisions.1,6 Factors that contribute to institutionalization of a PWD have been well-studied, and include higher caregiver burden, and worse functional impairment, cognitive impairment, and behavioral symptoms of dementia.7–9

Research has shown that CPs caring for PWD want more anticipatory guidance from clinicians related to institutionalization decisions,10–13 specific transitions (e.g. hospital to home),14 and dementia disease course.15 Provider guidance can ease caregivers’ feelings of guilt or doubt about the decision to move a PWD to a nursing home or other institutional facility.16 Negative interactions with providers, on the other hand, can increase dissatisfaction and burden, and decrease self-efficacy during transitions.16

Despite an understanding that caregivers benefit from anticipatory guidance on care setting, healthcare providers report uncertainty in approaching these conversations. In one study, family physicians reported feeling underprepared to counsel patients and their CPs on decision-making related to home or institutional care.17 Physicians at a memory care clinic similarly endorsed that patients and family often have questions about care setting decisions,18 yet no protocols exist to help physicians anticipate and address these concerns. The first step in establishing recommendations for healthcare providers who wish to counsel PWD and CPs on care setting is to identify what guidance is useful.

This study aimed to identify what guidance from healthcare providers will benefit CPs navigating care setting decisions throughout the dementia journey. While previous research focuses on the experience of early stage or end-of-life caregiving, this study compares the perspectives of CPs actively caring for PWD to those of former CPs of recently deceased patients. As such, we provide insight on CP needs at various stages of the dementia journey to aid healthcare providers who wish to support CPs navigating care setting decisions.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Collection

This study is a secondary data analysis that focuses on a concept that was present but not specifically addressed in the primary analysis. The parent study was a descriptive qualitative study19 that aimed to describe foundational data to inform the development of palliative care interventions. The parent study design was influenced by a palliative care biopsychosocial framework.19 Study data were semi-structured interviews with CPs of people with dementia conducted between November 2018 and July 2019.15,20 The interview guide, developed by an interdisciplinary team of experts in geriatrics, neurology, and palliative care, included questions about disease course, future expectations, and interactions with medical providers in caring for the PWD. This study was approved by the institutional review board and follows guidance of the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ).21 A summary of the study in the COREQ framework has been previously published as part of the original study.15,20

Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited from a tertiary memory clinic in an urban center and cared for a person with dementia, including Alzheimer’s dementia, corticobasal syndrome, Lewy body dementia, or a less common syndrome such as behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, primary progressive aphasia (PPA), or progressive supranuclear palsy Richardson’s syndrome (PSP-RS). CPs of patients were identified via chart review and the memory clinic provider of the patient was consulted to ensure a fit for the study.

Current CPs were identified as those caring for a community-dwelling patient with mild to moderate dementia (MMSE or MoCA >15). Former CPs were those who cared for a patient who had died with severe or advanced disease less than one year prior to recruitment. Included CPs spoke English without an interpreter and were not professional or paid caregivers. After the interview, participants completed a written questionnaire to report demographic characteristics.

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, deidentified by a research assistant, and uploaded into ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis and research software (9.1.2). In this secondary analysis we aimed to compare the experiences of current and former CPs of PWD. Three authors (KR, MH, and KLH) read all transcripts and KR deductively identified data related to home care and institutionalization to begin codebook development. Consistent with best practices of the constant comparative method,22,23 the study team cycled through multiple iterations of themes related to care setting, looking for unexpected and disconfirming evidence. Methods included the use of diagrams and memos to chart the care setting progression for each participant, which aided our ability to generate codes. Inductive codes captured elements of the care setting journey for each participant type, for example, differences in home or institutional care, informational needs related to transitions, and guidance that aided decision-making. Codes were applied by KR. KLH reviewed coded data for fidelity to codebook. Primary codes reflected primary themes and secondary codes reflected sub-themes; code definitions reflected minor themes and discrepant cases. The study team met regularly to ensure code accuracy and review emergent findings. After codes were applied, findings were synthesized. Data analysis was performed from June to December 2021.

RESULTS

Participants

Participants were 31 family CPs: 16 current and 15 former CPs. CPs had a mean age of 67 (range 40–87) and were primarily female (n=21/31, 68%). Participants were mostly spouses or partners (n=24/31, 77%), the remainder were adult children of the PWD (n=7/31, 23%). CPs were primarily white (n=23, 74%), had a college degree or higher (n=25/31, 81%), and a modal income category of $100,000 or higher. Five CPs (n=5/31, 16%) were LGBT spouses or domestic partners of the PWD. Demographics for the sample have been previously described.15,20

Current CPs were caring for patients with an average MMSE score of 17.4, indicating moderate dementia, available for 13/16 patients; 56% of PWD had a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s documented in the electronic health record (EHR) before recruitment. Among former CPs, 33% of their PWD had an Alzheimer’s diagnosis documented in the EHR and interviews were on average conducted eight months after the death of the PWD (range 3–12 months). In-person interviews lasted between 59 and 128 minutes (mean = 83).

Care Setting

All current CPs (N=16/16, 100%) were caring for the PWD in the home. Among former CPs, we identified three care setting arcs: home care, short-term institutionalization, and institutionalization. Six former CPs (N=6/15, 40%) cared for the patient at home, where the patient died. Three former CPs (N=3/15, 20%) experienced short-term institutionalization: they primarily cared for the PWD at home but describe periods in which the patient had short-term stays in non-home settings, such as a rehab hospital, nursing home, or assisted living facility, to later be discharged home. Finally, six former CPs (N=6/15, 40%) reported institutionalization in which the PWD moved into a long-term care facility without plans to return home. In total, most of the PWD in the former CP sample experienced short or long-term institutionalization during their care (N=9/15, 60%).

Themes

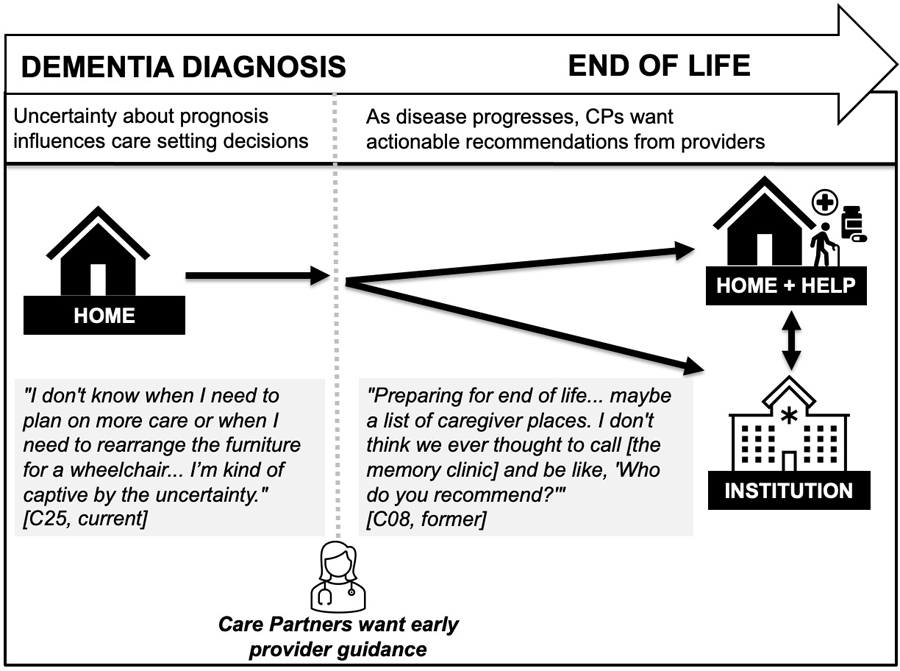

Below we summarize themes (Figure 1) organized according to temporality along the caregiving journey. We sought to compare the experiences of the two participant groups, reflecting their point of view at early or late phases of dementia. Theme 1 pertains to the current CPs who represent earlier stages of disease, theme 2 pertains to former CPs later in the disease.

Figure 1:

Visual summary of findings. Early in the dementia diagnosis, care partners express uncertainty while caring for the person with dementia at home. Later, care partners need help to stay at home or decide to move the person with dementia to an institution. The findings from this study illustrate the need for provider guidance throughout the disease course, particularly as the person with dementia approaches end of life.

Theme 1: Early in the disease course, current CPs want prognostic guidance to inform care setting decisions

Early in the disease journey, current CPs experienced overwhelming uncertainty pertaining to future care setting transitions. Some current CPs expressed a desire to keep the PWD in the home, for example stating, “Well, I’m going to keep [husband] with me for as long as possible, I mean, just as long as I can take care of him and able to do that, and then if it comes to a point where that’s not going to be feasible then I will look into some memory care homes, but I don’t think we’re at that stage yet” (C29, current).

However, despite a desire to keep the PWD in the home, most CPs did not have a plan to execute these wishes and were uncertain about future care. One current CP stated, “I mean, he’s certainly not bad enough yet [for a care facility] … I don’t know how bad somebody has to get. Somebody did say to me that when he doesn’t recognize me, then maybe that’s a time to do something… [Spouse] still has some ability to function, you know” (C10, current). Another participant noted, “I’m kind of a planful person. And I think my concerns are the uncertainty. I don’t know when I need to plan on more care or when I need to rearrange the furniture for a wheelchair; maybe I won’t have to. So I’m kind of captive by the uncertainty” (C25, current).

Current CPs wanted prognostic information about the PWD’s disease stage to anticipate level of care required and thus make decisions about care setting. For example, a current CP stated, “It would probably be good for him to see a neurologist to maybe get a full physical to see how he’s advancing… It would be kind of nice to know if there is such a thing as a stage what stage are we at kind of thing. That would be very helpful for me, because, like I said, I’m trying to make some changes in our living arrangement” (C29, current). Similarly, another participant was concerned about prognostic information, “I’m a person that deals a lot in percentages and odds. What are the percentages of the next stages? I mean, has she got a 50 percent chance of remaining kind of the way she is? Is there a 90 percent chance that in six months she’s going to really collapse?” (C18, current).

Another CP was concerned about life expectancy as it related to her desire to remodel their home: “People told me that some people [with dementia] live for 10, 20 years and some people live like another 7 or 9 years, start from beginning… and I ask the doctors at the [memory clinic] … they have no idea either. It’s just like I’m going to remodel in my home, so I like to, you know, to know when they reach that stage, whether they can do, whether they cannot do, and then what’s the most needed, you know” (C02, current).

Theme 2: Later in disease course, former CPs want provider resources about care setting

Subtheme: Desire for institutional recommendations

Former CPs who considered institutionalization wanted help finding long-term care facilities from their medical team. CPs wanted this guidance in the form of concrete suggestions about facilities and the timing for institutionalization. One former CP remarked that they wanted more support from their medical team, “I think it’s a bit more handholding… I almost wonder if an additional person that’s in your profile that is, again, one of these people who helps with these transitions. I can’t identify exactly what that would be, but I just remember how alone I felt during the period of time where [spouse] was needing to – something had to change at home. It was definitely leading up to a care facility” (C16, former). Similarly, another CP shared, “She was in a memory care facility, but I sure would’ve loved some help finding better places, different places in the city that were easier on me. (C11, former).

Former CPs reflected on both helpful and unhelpful guidance that they received from health care professionals when debating whether or when to institutionalize the PWD. One former CP who considered institutionalization but stayed at home with the PWD stated, “…his doctor and his son and I discussed that, that if the caregivers and I could no longer handle him physically, we might have to do that. I went and visited several care facilities for dementia patients…” (C15, former). Proactive and early guidance from health care professionals aided CPs in preparing for a possible transition to long-term care, even if they decided to keep the PWD at home.

On the other hand, some former CPs reported negative or disparaging comments from physicians that were unhelpful in navigating difficult decisions related to care setting. One former CP who sought out information about rehab hospitals and long-term care institutions but decided to keep the PWD at home stated, “…my internist, when I decided to put him in a facility, he said, ‘Oh, one of those places.’ I mean, he was quite shocked that I would do that” (C17, former).

Subtheme: Caregiving at home requires provider resources and preparation

The six former CPs who cared for the PWD at home until death described a multitude of resources required, including private full-time caregivers, medical equipment, and resources such as referrals to home hospice and home-based medical care programs. A former CP described the importance of a primary care provider’s advice in recognizing need for more caregiving support, stating, “… it also got to be just, you know, progressively more and more work, you know, to take care of her… and at some point, [primary care physician] kind of arranged a little family intervention to prevail on me to bring in caregivers… I’m sure it was the right thing for her to do and it didn’t bother me that she did it. It was just, you know, up to that point I was thinking that I could, you know, I could take care of [wife] myself” (C13, former).

A different CP who sought home healthcare from their doctor stated, “I told her doctor, ‘Enough is enough. I can’t do this,’ and then we made a decision that a doctor had to come to the house” (C03, former). In these examples, health care professionals facilitated home care for the CP and PWD by providing at-home resources and encouraging the CP to hire more help.

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study of CPs of PWD, we found that CPs want early, specific guidance from healthcare providers related to transitions between home and long-term care institutions. Our work shows that early after diagnosis, current CPs place importance on issues of prognostication, life expectancy, and expected disease course to make plans for their living environment while the PWD is living at home. Later, as uncovered by former CPs, caregivers want help identifying locations or institutionalization or finding home care resources. These findings are represented by two key themes that describe important differences as the CP progresses through the caregiving journey.

This study enriches the existing body of work related to care setting for PWD in that it elicits CP perspectives on what guidance will be useful at different points in the dementia journey. Research has established that CPs want support from healthcare providers in transitions from home to long-term care,10–12,24 but not how desired guidance may change as the PWD progresses from early diagnosis to end-of-life. While diagnostic disclosure has been a focus of dementia research and palliative dementia care has emerged as a critical domain that focuses on improving care at end-of-life,25 those CPs who find themselves caregiving between or into these stages remain understudied. By eliciting and comparing perspectives from CPs at various stages of the dementia journey, this study provides new insight on what specific guidance will be helpful.

This work underscores the importance of anticipatory guidance in dementia care, in which PWD and CPs are counseled on what to expect throughout the disease progression. Anticipatory guidance has been studied in the immediate aftermath of a dementia diagnosis26 and in end-of-life counseling,27,28 but remains an understudied domain for PWD and their CPs who are between these two stages. Limited research has demonstrated that PWD and CPs receive suboptimal anticipatory guidance related to prognosis and planning.15,20

Healthcare providers face limitations in their ability to counsel CPs and PWD because of insufficient time in appointments, insufficient reimbursement, and lack of expertise in dementia care.29–32 Even dementia experts identify challenges in communicating about difficult topics, including diagnostic disclosure and prognosis,33–35 and worry about disrupting their relationship with the patient and caregivers.18 Clinicians may worry about that providing PWD and CPs with information about dementia diagnosis and management may lead to psychological distress or erode hope.36,37 Yet, guidance is crucial to a CP’s ability to make plans and they want to hear it from trusted sources including physicians.

In addition, programs and policies are needed to enable CPs to care for PWD in both home and institutional settings. Examples include expanding financial compensation for family caregivers, improving access to home-based dementia care,38–40 and improving access to long-term care insurance policies.41 In 2016, the National Academy of Medicine recommended a national initiative to support the needs of caregivers, including through reimbursement programs, and increased funding for supportive services.42

Limitations

This study population may be representative of other tertiary memory centers but may not be transferrable to the wider community of people living with diagnosed or undiagnosed dementia syndromes. The study population was homogenous, representing mostly white, high-income and high-education English-speaking women, and limited to 31 CPs included. As such, the scope of the study was limited. CPs from different backgrounds and contexts likely require distinct supports from providers that meet their care transition needs in a culturally humble manner. As a secondary analysis, this study represented a narrowed scope of study compared to the parent study. Future investigation into this topic should consider using inductive methodology to generate novel theory.

CONCLUSIONS

Current and former CPs of PWD wanted increased support from providers to navigate care setting transitions. Providers should supply timely, concrete guidance related to care setting to improve CPs’ sense of uncertainty and their ability to navigate institutionalization or care at home.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate the study participants for their time to this project. Nicole Boyd helped with study administration and participant recruitment. Sarah Garrett, PhD, conducted data collection. Caroline Prioleau provided feedback on the figure. Research reported in this publication was conducted with support from the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI), NIH/NIA K01AG059831 (KH), Career Development Award from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (KL2TR001870 - KH); UCSF Hellman Fellows (KH); National Palliative Care Research Center Junior Faculty Award (KH); and Medical Student Training in Aging Research Program (T35AG026736).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.2022 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc 2022;18(4):700–789. doi: 10.1002/alz.12638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomes B, Calanzani N, Gysels M, Hall S, Higginson IJ. Heterogeneity and changes in preferences for dying at home: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:7. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodman C, Baillie J, Sivell S. The preferences and perspectives of family caregivers towards place of care for their relatives at the end-of-life. A systematic review and thematic synthesis of the qualitative evidence. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6(4):418–429. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, Brière N, et al. “Please listen to me”: A cross-sectional study of experiences of seniors and their caregivers making housing decisions. PloS One 2018;13(8):e0202975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashbourne J, Boscart V, Meyer S, Tong CE, Stolee P. Health care transitions for persons living with dementia and their caregivers. BMC Geriatr 2021;21(1):285. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02235-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Callahan CM, Tu W, Unroe KT, LaMantia MA, Stump TE, Clark DO. Transitions in Care in a Nationally Representative Sample of Older Americans with Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63(8):1495–1502. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toot S, Swinson T, Devine M, Challis D, Orrell M. Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Psychogeriatr 2017;29(2):195–208. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luppa M, Luck T, Brähler E, König HH, Riedel-Heller SG. Prediction of Institutionalisation in Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2008;26(1):65–78. doi: 10.1159/000144027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verbeek H, Meyer G, Challis D, et al. Inter-country exploration of factors associated with admission to long-term institutional dementia care: evidence from the RightTimePlaceCare study. J Adv Nurs 2015;71(6):1338–1350. doi: 10.1111/jan.12663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lord K, Livingston G, Robertson S, Cooper C. How people with dementia and their families decide about moving to a care home and support their needs: development of a decision aid, a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:68. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0242-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teng C, Loy CT, Sellars M, et al. Making Decisions About Long-Term Institutional Care Placement Among People With Dementia and Their Caregivers: Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. The Gerontologist 2020;60(4):e329–e346. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dellasega C, Mastrian K, Weinert C. The Process and Consequences of Institutionalizing an Elder. West J Nurs Res 1995;17(2):123–140. doi: 10.1177/019394599501700202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hainstock T, Cloutier D, Penning M. From home to ‘home’: Mapping the caregiver journey in the transition from home care into residential care. J Aging Stud 2017;43:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toles M, Leeman J, Gwyther L, Vu M, Vu T, Hanson LC. Unique Care Needs of People with Dementia and Their Caregivers during Transitions from Skilled Nursing Facilities to Home and Assisted Living: A Qualitative Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc Published online August 1, 2022:S1525-8610(22)00479-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2022.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Shafir A, Ritchie CS, Garrett SB, et al. “Captive by the Uncertainty”-Experiences with Anticipatory Guidance for People Living with Dementia and Their Caregivers at a Specialty Dementia Clinic. J Alzheimers Dis JAD 2022;86(2):787–800. doi: 10.3233/JAD-215203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caron CD, Ducharme F, Griffith J. Deciding on Institutionalization for a Relative with Dementia: The Most Difficult Decision for Caregivers*. Can J Aging Rev Can Vieil 2006;25(2):193–205. doi: 10.1353/cja.2006.0033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yaffe MJ, Orzeck P, Barylak L. Family physicians’ perspectives on care of dementia patients and family caregivers. Can Fam Physician 2008;54(7):1008–1015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein Sideman A, Harrison KL, Garrett SB, Naasan G, Group DPCW, Ritchie CS. Practices, challenges, and opportunities when addressing the palliative care needs of people living with dementia: Specialty memory care provider perspectives. Alzheimers Dement Transl Res Clin Interv 2021;7(1):e12144. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, Meier DE. National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines, 4th Edition. J Palliat Med 2018;21(12):1684–1689. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison KL, Garrett SB, Bernstein Sideman A, et al. “I didn’t sign up for this”: perspectives from persons living with dementia and care partners on challenges, supports, and opportunities to add geriatric neuropalliative care to dementia specialty care. J Alzheimers Dis 2022;Online ahead of print. doi: 10.3233/JAD-220536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boeije H A Purposeful Approach to the Constant Comparative Method in the Analysis of Qualitative Interviews. Qual Quant 2002;36(4):391–409. doi: 10.1023/A:1020909529486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rendle KA, Abramson CM, Garrett SB, Halley MC, Dohan D. Beyond exploratory: a tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research. BMJ Open 2019;9(8):e030123. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Afram B, Verbeek H, Bleijlevens MHC, Hamers JPH. Needs of informal caregivers during transition from home towards institutional care in dementia: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27(6):891–902. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214002154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: A Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28(3):197–209. doi: 10.1177/0269216313493685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yates J, Stanyon M, Samra R, Clare L. Challenges in disclosing and receiving a diagnosis of dementia: a systematic review of practice from the perspectives of people with dementia, carers, and healthcare professionals. Int Psychogeriatr 2021;33(11):1161–1192. doi: 10.1017/S1041610221000119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malhi R, McElveen J, O’Donnell L. Palliative Care of the Patient with Dementia. Del J Public Health 2021;7(4):92–98. doi: 10.32481/djph.2021.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahalt C, Walter LC, Yourman L, Eng C, Pérez-Stable EJ, Smith AK. “Knowing is Better”: Preferences of Diverse Older Adults for Discussing Prognosis. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27(5):568–575. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1933-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CarolinaApesoa-Varano E, Barker JC, Hinton L. Curing and Caring: The Work of Primary Care Physicians With Dementia Patients. Qual Health Res 2011;21(11):1469–1483. doi: 10.1177/1049732311412788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hinton L, Franz CE, Reddy G, Flores Y, Kravitz RL, Barker JC. Practice Constraints, Behavioral Problems, and Dementia Care: Primary Care Physicians’ Perspectives. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(11):1487–1492. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0317-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jensen CJ, Inker J. Strengthening the dementia care triad: identifying knowledge gaps and linking to resources. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2015;30(3):268–275. doi: 10.1177/1533317514545476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foley T, Boyle S, Jennings A, Smithson WH. “We’re certainly not in our comfort zone”: a qualitative study of GPs’ dementia-care educational needs. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0639-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey C, Dooley J, McCabe R. ‘How do they want to know?’ Doctors’ perspectives on making and communicating a diagnosis of dementia. Dementia 2019;18(7–8):3004–3022. doi: 10.1177/1471301218763904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holloway RG, Gramling R, Kelly AG. Estimating and communicating prognosis in advanced neurologic disease. Neurology 2013;80(8):764–772. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318282509c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kissel EC, Carpenter BD. It’s all in the details: physician variability in disclosing a dementia diagnosis. Aging Ment Health 2007;11(3):273–280. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karnieli-Miller O, Werner P, Aharon-Peretz J, Eidelman S. Dilemmas in the (un)veiling of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: walking an ethical and professional tight rope. Patient Educ Couns 2007;67(3):307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Low LF, McGrath M, Swaffer K, Brodaty H. Communicating a diagnosis of dementia: A systematic mixed studies review of attitudes and practices of health practitioners. Dement Lond Engl 2019;18(7–8):2856–2905. doi: 10.1177/1471301218761911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunt LJ, Harrison KL. Live discharge from hospice for people living with dementia isn’t “graduating”—It’s getting expelled. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(6):1457–1460. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunt LJ, Harrison KL, Covinsky KE. Instead of wasting money on aducanumab, pay for programs proven to help people living with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 2021;69(12):3690–3692. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ornstein KA, Ankuda CK, Leff B, et al. Medicare-funded home-based clinical care for community-dwelling persons with dementia: An essential healthcare delivery mechanism. J Am Geriatr Soc 2022;70(4):1127–1135. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kolanowski A, Fortinsky RH, Calkins M, et al. Advancing Research on Care Needs and Supportive Approaches for Persons With Dementia: Recommendations and Rationale. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018;19(12):1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Academies of Sciences E. Families Caring for an Aging America; 2016. doi: 10.17226/23606 [DOI] [PubMed]