Abstract

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease with a complex pathophysiology resulting in nonscarring hair loss in genetically susceptible individuals. We aim to provide health care decision makers an overview of the pathophysiology of AA, its causes and diagnosis, disease burden, costs, comorbidities, and information on current and emerging treatment options to help inform payer benefit design and prior authorization decisions.

Literature searches for AA were conducted using PubMed between 2016 and 2022 inclusive, using search terms covering the causes and diagnosis of AA, pathophysiology, comorbidities, disease management, costs, and impact on quality of life (QoL).

AA is a polygenic autoimmune disease that significantly impacts QoL. Patients with AA face economic burden and an increased prevalence of psychiatric disease, as well as numerous systemic comorbidities. AA is predominantly treated using corticosteroids, systemic immunosuppressants, and topical immunotherapy. Currently, there are limited data to reliably inform effective treatment decisions, particularly for patients with extensive disease. However, several novel therapies that specifically target the immunopathology of AA have emerged, including Janus kinase (JAK) 1/2 inhibitors such as baricitinib and deuruxolitinib, and the JAK3/tyrosine kinase expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (TEC) family kinase inhibitor ritlecitinib. To support disease management, a disease severity classification tool, the Alopecia Areata Severity Scale, was recently developed that evaluates patients with AA holistically (extent of hair loss and other factors).

AA is an autoimmune disease often associated with comorbidities and poor QoL, which poses a significant economic burden for payers and patients. Better treatments are needed for patients, and JAK inhibitors, among other approaches, may address this tremendous unmet medical need.

Plain language summary

Alopecia areata (AA) causes hair loss that can be hard to treat. It can impact the quality of life for adults and children and lead to poor attendance and performance at work or school. People with AA often have related health issues, and costs due to AA can be large. One treatment for AA is now approved for adults in the United States, and others have been shown to work in clinical studies.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

AA is an autoimmune disease often associated with other comorbidities and poor quality of life and poses an economic burden for payers and patients. The significant unmet medical need in the treatment of AA may be addressed by safe and effective therapeutic options that target the pathophysiology of disease. Decision makers, payers, and disease experts should carefully determine the best way of identifying appropriate patients for new treatments entering the marketplace.

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune1 disease with a lifetime incidence of approximately 2%.2 It is a T-cell–mediated nonscarring form of hair loss of the scalp, face, and/or body, with an underlying immunoinflammatory pathogenesis.3 Comorbid autoimmune diseases are common in AA. The course of disease is often unpredictable, with periods of relapse and remission, though severe disease is usually chronic. Treatment for AA differs from other forms of hair loss.

Currently, the Janus kinase (JAK)1/2 inhibitor baricitinib is the only approved therapy (in some countries) for the treatment of severe AA.4 Off-label treatments have limited tolerability and effectiveness. Frequent comorbidities and the psychosocial impact on patients contribute to the significant health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs associated with AA.5-7

The objective of this narrative review is to provide an overview of AA, including the genetic and autoimmune pathobiology, its differentiation from other forms of hair loss, common comorbidities, and treatment options. We also discuss the clinical, economic, and social burden of disease and the methods used to assess AA severity, which may be important to identify appropriate patients for treatment.

Literature Database Search Methods and Study Selection

Relevant studies were identified by an electronic literature search using the MEDLINE PubMed database between 2016 and 2021, inclusive, with a repeat search performed in January 2023 for any new publications. Searches included the following terms: alopecia areata AND (totalis OR universalis), (treat* OR therap*), ([treat* OR therap*] AND [fail* OR relaps* OR resist*]), gene*, (pathophysiology OR pathogenesis), (inflammation OR autoimmune* OR polyautoimmun*), (comorb* OR atopic dermatitis OR diabet* OR [diabetes mellitus] OR [rheumatoid arthritis] OR rheumat* OR thyroid OR [systemic lupus erythematosus] OR vitiligo OR anxiety OR depress* OR hyperlipidemia OR hypertension OR obes*OR anem* OR psoriasis), severity, burden, (psycho* OR [quality of life] OR psychosocial), (patient reported OR patient-reported), incidence, prevalence, economic* OR cost* OR (direct cost*) OR (indirect cost*) OR (healthcare cost*), ([unmet need*] OR need*). The title and abstract of identified citations were screened for potential eligibility. Articles published prior to 2016 that were considered by the authors to be particularly relevant were also included.

Prevalence, Incidence, Natural History, and Clinical Spectrum of AA

The most common nonscarring (ie, the hair follicle is preserved, allowing for hair regrowth) hair loss disease is androgenetic alopecia, which, as the name implies, is often an androgen hormone–dependent form of alopecia and affects up to 80% of men and 50% of women in their lifetime.8 Telogen effluvium is another form of nonscarring alopecia that results from profound biological stress (e.g., COVID-19 infection) and usually resolves spontaneously. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is a scarring alopecia that typically presents as a patch of hair loss on the crown that enlarges over time. Although most often seen in women of African descent, it may occur in men and women of all races.

AA is the second most common form of alopecia and affects people of all ages, races, and sexes,9 with male and female persons similarly affected.2,10 Most patients experience disease onset by age 40, with a mean age of onset ranging from 25-36 years.2,10 The National Alopecia Areata Foundation Registry (n = 2218) reports a mean age of onset in children of 5.9±4.1 years.11 A random-effects meta-analysis suggested global prevalence is significantly lower in adults (1.47% [1.18-1.80]) than in children (1.92% [1.31-2.65]; P < 0.0001).12

AA is usually a relapsing and remitting disease in which patches of hair loss occur unpredictably and resolve spontaneously, followed by variable periods of remission. However, typically in patients with more extensive hair loss, disease is persistent. The lifetime incidence of AA is 2%,2 and an estimated 8.2 million people in the United States have had AA.9 A cross-sectional US survey reported point prevalence of AA by disease severity. Point prevalence was 0.21% (95% CI = 0.17%-0.25%) overall; 0.12% (95% CI = 0.09%-0.15%) for mild disease (defined in the study as Severity of Alopecia Tool [SALT] score ≤ 50 [vida infra], indicating ≤ 50% scalp-hair loss); and 0.09% (95% CI = 0.06%-0.11%) for moderate to severe disease (SALT score > 50).9 Point prevalence for the most extensive scalp-hair loss (alopecia totalis [AT] and alopecia universalis [AU], SALT score of 100 or complete scalp with or without body hair loss) was 0.04% (95% CI = 0.02%-0.06%). The data suggest that approximately 700,000 people currently live with AA in the United States, including approximately 300,000 with a SALT score of > 50, of whom up to half may have AT or AU.9

Diagnosis of AA and Disease Severity

Diagnosis of AA is usually based on clinical observation. A positive hair pull test or trichoscopy may be helpful in diagnosing AA13; rarely, histopathology is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.14 In addition to hair loss, up to 44% of patients present with nail abnormalities, often in more extensive cases of AA.15

The most common AA subtypes include (1) patchy AA, the most common form, characterized by round/oval patches of hair loss on the scalp or other parts of the body; (2) ophiasis AA, hair loss involving the posterior hairline and extending to above the ears; (3) AT, complete loss of scalp hair; and (4) AU, complete loss of scalp, face, and body hair.16 However, these classifications do not fully assess severity and are inadequate as they poorly characterize the clinical spectrum of disease and do not correlate with prognosis,17 and definitions of AT and AU vary widely.18

Clinically meaningful tools for assessing disease severity in AA are important for clinical decision-making and clinical trials. The SALT is a validated instrument that assesses the amount of scalp-hair loss, with SALT scores ranging from 0 (no scalp-hair loss) to 100 (complete scalp-hair loss)19 (Supplementary Table 1 (926KB, pdf) , available in online article); the SALT score is used in clinical trials but not in daily practice. Anchored in the SALT score, the Alopecia Areata Investigator Global Assessment20 was developed to detail clinically meaningful categories of scalp-hair loss that reflect patients’ and expert clinicians’ perspectives and treatment expectations. The Alopecia Areata Scale was developed by expert consensus and is amenable for use in daily clinical practice.21 It is the only tool that accounts for scalp-hair loss along with other important disease features, including involvement of other body locations (eg, eyebrows, eyelashes), treatment responsiveness, and the psychosocial impact of disease.

AA Genetics and Pathophysiology

AA is an autoimmune disease.14 Therefore, in contrast to androgenetic alopecia, AA has an immunoinflammatory pathogenesis. Hair loss in AA results from immune privilege collapse22 and CD8+ T-cell attack of hair follicles, mediated by interferon-γ, interleukin (IL)-15, and other cytokines, some of which signal through JAK proteins.23 The hair follicle is not destroyed, and hair is able to regrow if the inflammatory process is suppressed.

Comorbidities

Comorbid autoimmune and inflammatory diseases in patients with AA are common, and shared genetics and immune pathways may be involved.24,25 Multiple genes associated with AA are also linked with other autoimmune diseases, and associations between these diseases and AA have been found.25-36

The interplay between AA and comorbid psychiatric disorders is complex, with contributions from genetic and environmental factors.37 One large population-based retrospective cohort study reported that patients with AA have a 34% greater risk of developing major depressive disorder than the general population and that having major depressive disorder was a risk factor for the development of AA.38 Additional studies have found an increased prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with AA.39-43

Impact of AA on Patient Quality of Life

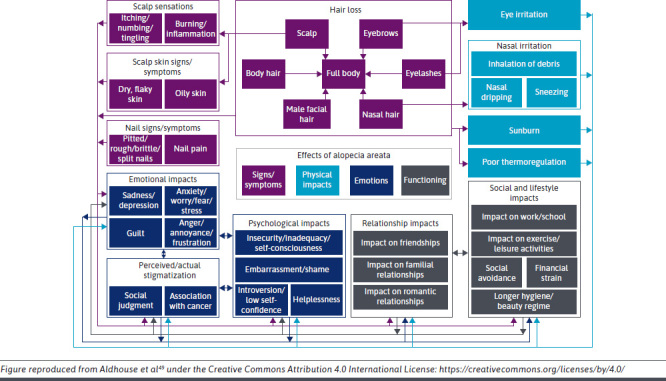

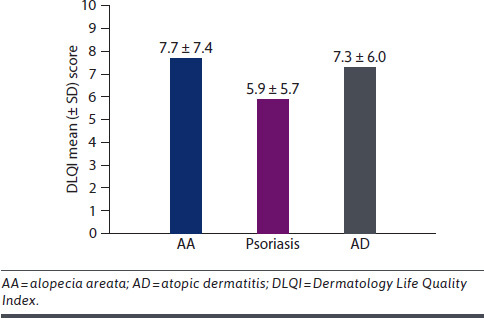

AA can have a profoundly negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL).10,44 It can affect self-perception/self-esteem, mental health/well-being, and relationships (Figure 1).45-47 Many patients describe a negative impact of AA on their professional life, having to take time off from work and having poor performance because of stress and lack of confidence due to AA.48,49 For children and adolescents with AA, the condition can result in missing school, performing poorly, and even discontinuing education; increased rates of bullying are reported in children and adolescents with AA.48,50-52 Several studies have shown that AA can have a profound impact on HRQoL that is similar to or worse than that of other dermatological diseases, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis53,54 (Figure 2). AA also affects the HRQoL of spouses/partners and families of patients (Supplementary Figure 1 (926KB, pdf) ).53,55 However, with successful treatment, patients with AA experience a positive impact on HRQoL.56

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual Model of the Physical and Psychosocial Burden of Alopecia Areata49

FIGURE 2.

Health-Related Quality of Life for Patients With AA vs Other Dermatological Conditions53,54

Economic Burden of AA

In addition to a significant psychosocial burden, AA presents an economic burden to patients. In a cross-sectional, quantitative-qualitative survey in patients with self-reported AA, respondents reported seeing a range of health care professionals for disease management, including dermatologists (89%), primary care physicians (61%), and psychological or behavioral health specialists (23%).48 Almost half of the 216 respondents did not have US insurance coverage for treatment and described treatment costs up to a mean of US$1,961 per year for counseling and/or therapy. In an analysis of 14,792 adults with AA and 44,916 controls, mean total all-cause medical and pharmacy costs were higher in patients with AA than in controls ($13,686 for non-AT/AU group vs $9,336 for matched controls; $18,988 for AT/AU group vs $11,030 for matched controls; P < 0.001 for both).5 Patient out-of-pocket costs were also significantly higher for patients with AA than for controls.5 These results align with the significantly greater HCRU and costs relative to matched controls in a large retrospective analysis of patients with AA and matched controls.6 Significantly higher HCRU and all-cause costs have also been shown in adolescents with AA than in matched controls (total payer costs of $7,587 for non-AT/AU subgroup vs $4,496 for matched controls; $9,397 for AT/AU subgroup vs $2,267 for matched controls; P < 0.001 for both).7 In a survey of 675 patients with AA, more than half reported moderate or serious financial burden of AA, with the greatest out-of-pocket costs being for headwear/cosmetic options, vitamins, supplements, or other treatments, as well as copays/out-of-pocket deductibles for doctor visits.57 Another study highlighted a lack of medical insurance coverage for concealment strategies, with a mean cost of approximately $2,200 per year.48

Current and Emerging Treatment Options

The appropriate treatment for patients with AA should consider several factors, including the extent and location of scalp-hair loss, involvement of frontal hairline or mid-scalp, duration of AA, and psychosocial impact of disease.58,59 In 2020, prior to the approval of a treatment for AA, the Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts, a global network of dermatologists with recognized expertise in hair and scalp disorder management, commented that “robust treatment efficacy data for AA are limited.”58 It is therefore unsurprising that patients with AA are dissatisfied with traditional treatments.60 In evidence of this, the National Alopecia Areata Foundation survey of more than 1,000 patients with AA reported that 78% were “very” or “somewhat unsatisfied” with their current medical treatments.60 Regardless of treatment, relapse rates are high when patients with extensive AA discontinue treatment61; therefore, maintenance therapy is usually necessary, although many therapies limit long-term use because of their adverse-effect profiles.

LIMITED HAIR LOSS (TOPICAL THERAPIES)

Corticosteroids (intralesional or topical) are often used as first-line therapy for limited scalp-hair loss. Although intralesional corticosteroids are the most effective treatment, patient age must be considered.58,59 Treatment of 20% scalp-hair loss with intralesional corticosteroids may require 70 or more injections. Because this treatment is painful and may be needed monthly for a few or more months, it may be inappropriate in children and those with more extensive hair loss.

Topical immunotherapies, such as diphenylcyclopropenone or squaric acid dibutylester, cause allergic contact dermatitis, which leads to changes in the immune environment of hair follicles.62 The goal of treatment is, in a sense, to cause itchy and red skin, and so topical immunotherapy is usually reserved for cases of limited scalp-hair loss. Diphenylcyclopropenone and squaric acid dibutylester are not commercially available, must be compounded, and are uncommon.59

MODERATE TO SEVERE HAIR LOSS (SYSTEMIC THERAPIES)

High doses of systemic corticosteroids can be effective for more extensive hair loss, but relapse rates are high, and long-term use is associated with numerous adverse events.63

Steroid-sparing immunosuppressants are rarely effective as monotherapy for the treatment of AA. In a retrospective study of 138 patients with AA receiving cyclosporine, methotrexate, or azathioprine, concurrent prednisolone was necessary in 58%, 64%, and 67% of patients, respectively, to achieve results meriting continued therapy after 12 months.64

EMERGING THERAPIES

Recent advances in our understanding of AA pathogenesis have led to targeted therapy of this autoimmune disease. JAK inhibitors are being evaluated in large, randomized phase 2 and 3 trials in patients with AA with ≥ 50% scalp-hair loss; in these trials, approximately half of patients have complete scalp-hair loss, and many have eyebrow and eyelash loss.

The JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib is approved for AA by the US Food and Drug Administration.4 In the phase 3 BRAVE-AA1 trial (NCT03570749), 39% and 23% of patients receiving baricitinib 4 mg and 2 mg, respectively, had response based on SALT ≤ 20 at week 36 compared with 6% of patients receiving placebo (Supplementary Table 2 (926KB, pdf) ).65 Similar results were demonstrated in BRAVE-AA2 (NCT03899259).65

The JAK3/TEC family kinase inhibitor ritlecitinib was evaluated in the ALLEGRO 2b/3 trial in patients aged 12 years and older and with ≥ 50% hair loss (NCT03732807): 31%, 22%, 23%, and 14% of patients receiving ritlecitinib 200/50 mg, 200/30 mg, 50 mg, and 30 mg, respectively, had response based on SALT ≤ 20 at week 24 compared with 2% of patients receiving placebo.66

The JAK1/2 inhibitor deuruxolitinib (formerly CTP-543) was evaluated in the THRIVE-AA1 trial (NCT04518995): 42% and 30% of patients receiving deuruxolitinib 12 mg and 8 mg, respectively, had response based on SALT ≤ 20 at week 24 compared with 1% of patients receiving placebo.67 Similar results were seen in the THRIVE-AA2 trial (NCT04797650).68

Phase 3 trials of the JAK1/2/3 inhibitor jaktinib (NCT05051761) and the JAK1 inhibitor ivarmacitinib (NCT05470431) are ongoing.

Notably, in the 2020 Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts, there was agreement that if treatments were reimbursed equally, “JAK inhibitors would be the ideal choice of systemic therapy” in adults with AA.58

Other investigational agents for the treatment of AA with completed or ongoing trials include dupilumab, an IL-4 and IL-13 inhibitor (NCT03359356)69; etrasimod, a selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator (NCT04556734); deucravacitinib, a TYK2 inhibitor (NCT05556265); daxdilimab, an ILT7 monoclonal antibody (NCT05368103); and EQ101, a multitarget IL-2, IL-9, and IL-15 inhibitor (NCT05589610).

LIMITATIONS

A broad literature search was undertaken to cover multiple aspects of AA for this review; however, relevant articles may have been excluded because of the search terms chosen.

Additionally, the lack of systematic review methodology may have resulted in potential bias in the articles chosen.

Summary

AA is an autoimmune disease that can affect genetically predisposed individuals. Patients with AA commonly experience other autoimmune comorbidities,25,27,28 and disease can have a negative impact on HRQoL, resulting in poor attendance and performance at work or school.48 The number of people in the United States living with AA with a SALT score > 50 is estimated at 300,000.9 The significant unmet medical need of patients with AA70 may be addressed by safe and effective treatment options that target the pathophysiology of disease.

Multiple emerging treatments are expected to soon be approved for the treatment of AA in adolescents and adults. Health care decision makers will need to determine their approach to evaluating AA treatments to provide care to their members with AA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support for the article was provided by Katy Beck, PhD, and David Sunter, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions and Nicola Gillespie, DVM, of Health Interactions and was funded by Pfizer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20(9):1043-9. doi:10.1038/nm.3645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mirzoyev SA, Schrum AG, Davis MDP, Torgerson RR. Lifetime incidence risk of alopecia areata estimated at 2.1% by Rochester Epidemiology Project, 1990-2009. J Invest Dermatol. 2014; 134(4):1141-2. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simakou T, Butcher JP, Reid S, Henriquez FL. Alopecia areata: A multifactorial autoimmune condition. J Autoimmun. 2019;98:74-85. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first systemic treatment for alopecia areata. 2022. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-systemic-treatment-alopecia-areata

- 5.Mostaghimi A, Gandhi K, Done N, et al. All-cause health care resource utilization and costs among adults with alopecia areata: A retrospective claims database study in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(4):426-34. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.4.426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mostaghimi A, Xenakis J, Meche A, Smith TW, Gruben D, Sikirica V. Economic burden and healthcare resource use of alopecia areata in an insured population in the USA. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12(4):1027-40. doi:10.1007/s13555-022-00710-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray M, Swallow E, Gandhi K, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs among US adolescents with alopecia areata. J Health Econ Outcomes Res. 2022;9(2):11-8. doi:10.36469/001c.36229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alessandrini A, Starace M, D’Ovidio R, et al. Androgenetic alopecia in women and men: Italian guidelines adapted from European Dermatology Forum/European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology guidelines. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155(5):622-31. doi:10.23736/s0392-0488.19.06399-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benigno M, Anastassopoulos KP, Mostaghimi A, et al. A large crosssectional survey study of the prevalence of alopecia areata in the United States. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:259-66. doi:10.2147/CCID.S245649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: A systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2015;8:397-403. doi:10.2147/CCID.S53985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wohlmuth-Wieser I, Osei JS, Norris D, et al. Childhood alopecia areata-data from the National Alopecia Areata Registry. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(2):164-9. doi:10.1111/pde.13387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):675-82. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Darwin E, Hirt PA, Fertig R, Doliner B, Delcanto G, Jimenez JJ. Alopecia areata: Review of epidemiology, clinical features, pathogenesis, and new treatment options. Int J Trichology. 2018;10(2):51-60. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_99_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt CH, King LE, Jr., Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trüeb RM, Dias MFRG. Alopecia areata: A comprehensive review of pathogenesis and management. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):68-87. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8620-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juarez-Rendon KJ, Rivera Sanchez G, Reyes-Lopez MA, et al. Alopecia areata. Current situation and perspectives. Article in Spanish. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115(6):e404-11. doi:10.5546/aap.2017.eng.e404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wambier CG, King BA. Rethinking the classification of alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):e45. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterson DM, Craiglow BG, Mesinkovska NA, Ko J, Senna MM, King BA. It is all alopecia areata: It is time to abandon the terms alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;S0190-9622(21):02571-8. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.09.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsen EA, Hordinsky MK, Price VH, et al. Alopecia areata investigational assessment guidelines--Part II. National Alopecia Areata Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(3):440-7. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wyrwich KW, Kitchen H, Knight S, et al. The Alopecia Areata Investigator Global Assessment scale: A measure for evaluating clinically meaningful success in clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):702-9. doi:10.1111/bjd.18883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.King BA, Mesinkovska NA, Craiglow B, et al. Development of the alopecia areata scale for clinical use: Results of an academic-industry collaborative effort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;86(2):359-64. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.08.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ito T, Kageyama R, Nakazawa S, Honda T. Understanding the significance of cytokines and chemokines in the pathogenesis of alopecia areata. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29(8):726-32. doi:10.1111/exd.14129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Divito SJ, Kupper TS. Inhibiting Janus kinases to treat alopecia areata. Nat Med. 2014;20(9):989-90. doi:10.1038/nm.3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu SY, Chen YJ, Tseng WC, et al. Comorbidity profiles among patients with alopecia areata: The importance of onset age, a nationwide population-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5):949-56. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee S, Lee H, Lee CH, Lee WS. Comorbidities in alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(2):466-77.e16. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petukhova L, Duvic M, Hordinsky M, et al. Genome-wide association study in alopecia areata implicates both innate and adaptive immunity. Nature. 2010;466(7302):113-7. doi:10.1038/nature09114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee NR, Kim BK, Yoon NY, Lee SY, Ahn SY, Lee WS. Differences in comorbidity profiles between early-onset and late-onset alopecia areata patients: A retrospective study of 871 Korean patients. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(6):722-6. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghaffari J, Rokni GR, Kazeminejad A, Abedi H. Association among thyroid dysfunction, asthma, allergic rhinitis and eczema in children with alopecia areata. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(3):305-9. doi:10.3889/oamjms.2017.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung JM, Yang HJ, Lee WJ, Won CH, Lee MW, Chang SE. Association between psoriasis and alopecia areata: A systematic review and metaanalysis. J Dermatol. 2022;49(9):912-5. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egeberg A, Anderson S, Edson-Heredia E, Burge R. Comorbidities of alopecia areata: A population-based cohort study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46(4):651-6. doi:10.1111/ced.14507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutierrez Y, Pourali SP, Jones ME, et al. Alopecia areata in the United States: A ten-year analysis of patient characteristics, comorbidities, and treatment patterns. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27(10). doi:10.5070/d3271055631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moseley IH, Thompson JM, George EA, et al. Immune-mediated diseases and subsequent risk of alopecia areata in a prospective study of US women. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022. doi:10.1007/s00403-022-02444-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chanprapaph K, Mahasaksiri T, Kositkuljorn C, Leerunyakul K, Suchonwanit P. Prevalence and risk factors associated with the occurrence of autoimmune diseases in patients with alopecia areata. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:4881-91. doi:10.2147/jir.s331579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maghfour J, Olson J, Conic RRZ, Mesinkovska NA. The association between alopecia and inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dermatology. 2021;237(4):658-72. doi:10.1159/000512747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kridin K, Renert-Yuval Y, Guttman-Yassky E, Cohen AD. Alopecia Areata is associated with atopic diathesis: Results from a population-based study of 51,561 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(4):1323-8.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2020.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Senna M, Ko J, Tosti A, et al. Alopecia areata treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and comorbidities in the US population using insurance claims. Adv Ther. 2021;38(9):4646-58. doi:10.1007/s12325-021-01845-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(16):1515-25. doi:10.1056/NFJMra1103442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vallerand IA, Lewinson RT, Parsons LM, et al. Assessment of a bidirectional association between major depressive disorder and alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(4):475-9. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang KP, Mullangi S, Guo Y, Qureshi AA. Autoimmune, atopic, and mental health comorbid conditions associated with alopecia areata in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(7):789-94. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among patients with alopecia areata (AA): A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(4):806-12.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abedini R, Hallaji Z, Lajevardi V, Nasimi M, Karimi Khaledi M, Tohidinik HR. Quality of life in mild and severe alopecia areata patients. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4(2):91-4. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lauron S, Plasse C, Vaysset M, et al. Prevalence and odds of depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms in children and adults with alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2023. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.6085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzur Bitan D, Berzin D, Kridin K, Cohen A. The association between alopecia areata and anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder: A population-based study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022;314(5):463-8. doi:10.1007/s00403-021-02247-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubois M, Baumstarck-Barrau K, Gaudy-Marqueste C, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: A study of 60 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(12):2830-3. doi:10.1038/jid.2010.232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burns LJ, Mesinkovska N, Kranz D, Ellison A, Senna MM. Cumulative life course impairment of alopecia areata. Int J Trichology. 2020;12(5):197-204. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_99_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mostaghimi A, Napatalung L, Sikirica V, et al. Patient perspectives of the social, emotional and functional impact of alopecia areata: A systematic literature review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(3):867-83. doi:10.1007/s13555-021-00512-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ö Aşkın, Koyuncu Z, Serdaroğlu S. Association of alopecia with self-esteem in children and adolescents. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2022;34(5):315-8. doi:10.1515/ijamh-2020-0100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, Ko J, Cassella J. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: A cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20(1):S62-8. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2020.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aldhouse NVJ, Kitchen H, Knight S, et al. “’You lose your hair, what’s the big deal?’ I was so embarrassed, I was so self-conscious, I was so depressed:” A qualitative interview study to understand the psychosocial burden of alopecia areata. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):76. doi:10.1186/s41687-020-00240-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Christensen T, Yang JS, Castelo-Soccio L. Bullying and quality of life in pediatric alopecia areata. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;3(3):115-8. doi:10.1159/000466704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barton VR, Toussi A, Awasthi S, Kiuru M. Treatment of pediatric alopecia areata: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(6):1318-34. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macey J, Kitchen H, Aldhouse NVJ, et al. A qualitative interview study to explore adolescents’ experience of alopecia areata and the content validity of sign/symptom patient-reported outcome measures. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(5): 849-60. doi:10.1111/bjd.20904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Alopecia areata is associated with impaired health-related quality of life: A survey of affected adults and children and their families. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):556-8 e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lundberg L, Johannesson M, Silverdahl M, Hermansson C, Lindberg M. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80(6):430-4. doi:10.1080/000155500300012873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Putterman E, Patel DP, Andrade G, et al. Severity of disease and quality of life in parents of children with alopecia areata, totalis, and universalis: A prospective, cross-sectional study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1389-94. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu LY, Craiglow BG, King BA. Successful treatment of moderate-to-severe alopecia areata improves health-related quality of life. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3):597-9.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li SJ, Mostaghimi A, Tkachenko E, Huang KP. Association of out-of-pocket health care costs and financial burden for patients with alopecia areata. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(4):493-4. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.5218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meah N, Wall D, York K, et al. The Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts (ACE) study: Results of an international expert opinion on treatments for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(1):123-30. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, et al. Alopecia areata: An appraisal of new treatment approaches and overview of current therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):15-24. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hussain ST, Mostaghimi A, Barr PJ, Brown JR, Joyce C, Huang KP. Utilization of mental health resources and complementary and alternative therapies for alopecia areata: A U.S. survey. Int J Trichology. 2017;9(4):160-4. doi:10.4103/ijt.ijt_53_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cranwell WC, Lai VW, Photiou L, et al. Treatment of alopecia areata: An Australian expert consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60(2):163-70. doi:10.1111/ajd.12941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Happle R. Topical immunotherapy in alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96(5):71-2S. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12471884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lai VWY, Chen G, Gin D, Sinclair R. Systemic treatments for alopecia areata: A systematic review. Australas J Dermatol. 2019;60(1):e1-13. doi:10.1111/ajd.12913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lai VWY, Sinclair R. Utility of azathioprine, methotrexate and cyclosporine as steroid-sparing agents in chronic alopecia areata: A retrospective study of continuation rates in 138 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(11):2606-12. doi:10.1111/jdv.16858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, et al. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(18):1687-99. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2110343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.King B, Zhang X, Gubelin Harcha W, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: A randomised, double-blind, multicentre phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10387):1518-29. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00222-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.King B. Top-line results from THRIVE-AA1: A phase 3 clinical trial of CTP-543 (deuruxolitinib), an oral JAK inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata. 31st Annual Meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). 2022. [abstract 3473]. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://eadv.org/scientific/abstract-books/

- 68.Koenigsberg J, Morris K. Concert Pharmaceuticals reports positive topline results for second CTP-543 phase 3 clinical trial in alopecia areata. 2022. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://ir.concertpharma.com/news-releases/news-release-details/concert-pharmaceuticals-reports-positive-topline-results-second

- 69.Guttman-Yassky E, Renert-Yuval Y, Bares J, et al. Phase 2a randomized clinical trial of dupilumab (anti-IL-4Ra) for alopecia areata patients. Allergy. 2022;77(3):897-906. doi:10.1111/all.15071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration. The voice of the patient. A series of reports from the US Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative. Alopecia areata. Accessed July 21, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/files/about%20fda/published/Alopecia-Areata--The-Voice-of-the-Patient.pdf

- 71.Olsen EA, Canfield D. Salt II: A new take on the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) for determining percentage scalp hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1268-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Olsen EA, Roberts J, Sperling L, et al. Objective outcome measures: Collecting meaningful data on alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]