Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patients with COVID-19 receiving ritonavir-containing therapies are at risk of potential drug-drug interactions (pDDIs) because of ritonavir’s effects on cytochrome P450 3A4.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the prevalence of pDDIs with ritonavir-containing COVID-19 therapy in adults with COVID-19 using the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart database.

METHODS:

In this retrospective, observational cohort study, patients with COVID-19 aged 18 years or older prescribed cytochrome P450 3A4–mediated medications with supply days overlapping the date of COVID-19 diagnosis between January 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, were classified as having pDDIs. pDDI was classified as contraindicated, major, moderate, or mild using established drug interaction resources. Prevalence of pDDIs with ritonavir-containing COVID-19 therapy was estimated for the entire cohort and in patient groups with high risk of severe COVID-19 progression or pDDIs. Actual COVID-19 treatments received by the patients, if any, were not considered. Outcomes were presented descriptively without adjusted comparisons.

RESULTS:

A total of 718,387 patients with COVID-19 were identified. The age-sex standardized national prevalence of pDDIs of any severity was estimated at 52.2%. Approximately 34.5% were at risk of contraindicated or major pDDIs. Compared with patients without pDDI, patients exposed to pDDIs were older and more likely to be female, reside in long-term care facilities, and have risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19. Higher prevalence of major/contraindicated pDDIs was observed in older patients (76.1%), female patients (65.0%), and patients with multiple morbidities (84.6%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Study findings demonstrate that more than one-third of patients with COVID-19 were at risk of significant pDDIs if treated with ritonavir-containing COVID-19 therapy and highlight the need to assess all patients with COVID-19 for pDDIs. Ritonavir-based therapies may not be appropriate for certain patient groups, and alternative therapies should be considered.

Plain language summary

Patients with COVID-19 treated with ritonavir are at risk of potential interactions with other medications. In this study, more than half of patients were at risk of having a potential drug interaction. Patients with potential drug interactions were older and more likely to be female, live in long-term care, and be at risk of having severe COVID-19. Medications that do not contain ritonavir should be considered for patients who are at risk of drug interactions.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

In this study, 52.2% of patients treated with ritonavir-containing COVID-19 therapy were at risk of potential drug-drug interactions with concomitant medications, highlighting certain patient groups that may be at higher risk of interactions. Therefore, there is a need to assess all candidates for ritonavir-containing COVID-19 therapy for potential drug-drug interactions, and alternative therapies should be considered for those at high risk.

More than 1 million deaths have occurred in the United States as a result of COVID-19 since January 2020.1 Older patients and patients with multiple morbidities are more likely to become infected with COVID-19 and progress to severe disease compared with younger patients and those without comorbidities.1,2 Outcomes in these high-risk patients are further complicated by potential drug-drug interactions (pDDIs) between medications used to treat underlying conditions and those prescribed to treat COVID-19.3

Two oral antiviral treatments, molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, have been granted emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19, who are at risk of progression to severe disease.4,5 Nirmatrelvir/ritonavir consists of the protease inhibitors nirmatrelvir, which disrupts SARS-CoV-2 viral replication, and ritonavir, which is not active against SARS-CoV-2 but is used as a pharmacokinetic boosting agent to increase plasma concentrations of nirmatrelvir. Ritonavir boosts nirmatrelvir by inhibiting cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), the isoenzyme primarily responsible for metabolizing several commonly prescribed medications, including nirmatrelvir.6 Its potent inhibition of CYP3A46 increases the risk of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) when used concomitantly with other drugs.

Several studies have reported DDIs with ritonavir-containing medications in patients with COVID-19.7-11 In one study, 87.4% of patients treated for COVID-19 were observed to experience treatment-related DDIs8; approximately 50% of observed DDIs were associated with lopinavir/ritonavir (used previously to treat COVID-19). Another study reported that 37.6% of observed pDDIs in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 involved the administration of lopinavir/ritonavir.11 Other studies have reported DDIs in patients with COVID-19 treated with darunavir/ritonavir.9 Ritonavir-based DDIs have been shown to result in severe drug-related adverse events, including QTc interval prolongation, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disorders, hematologic abnormalities, and psychiatric disorders, especially among older patients with critical illness. Alteration of blood levels of concomitantly administered medications such as lithium, aripiprazole, fentanyl, and digoxin has also been reported.9-11 Information on pDDIs with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir has been published by the FDA and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) COVID-19 guideline panel, with several medications listed as contraindicated with concomitant ritonavir use.6,12

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues and evolves, data to inform and optimize COVID-19 management strategies are urgently needed, especially for patients at high risk of progression to severe disease or who are susceptible to drug-related adverse events. This observational retrospective database study descriptively quantified the prevalence of pDDIs with ritonavir-containing COVID-19 therapy in the United States.

Methods

DATA SOURCE

This study used administrative claims data from January 1, 2019, to June 30, 2021, from the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart database. This large-scale database covers 15 million commercially and Medicare Advantage–enrolled members from all census regions of the United States. Collected information includes patient demographics, insurance enrollment history, prescription, medical (ie, inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department visits), and laboratory claims of beneficiaries. Patient data are deidentified and comply with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. As a result, no institutional review board approval was required.

STUDY POPULATION AND STUDY DESIGN

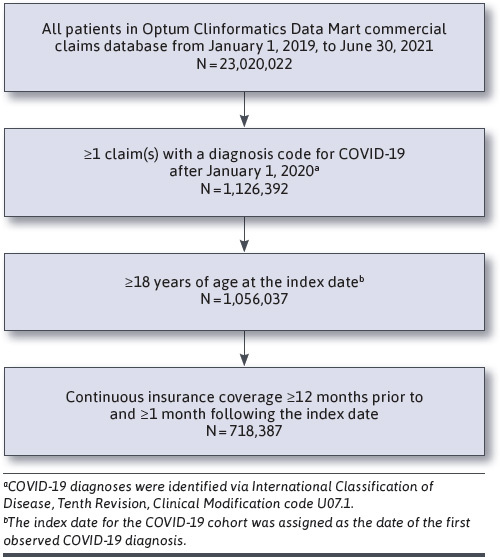

This study used a retrospective, observational cohort study design. Adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 infection (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] code U07.1) from any medical setting between January 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, were identified from the database. Patients were required to be aged 18 years or older at the index date (defined as the first date of confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis) and continuously enrolled in the health plan with medical and pharmacy benefits for at least 12 months prior to, and at least 1 month after, the index date. The 12-month period prior to the index date was defined as the baseline period. Patients were classified as having a pDDI (ie, “pDDI group”) if they had pharmacy fills for any CYP3A4-mediated medication with days supplied overlapping with the index date. Patients with a COVID-19 diagnosis but no pharmacy fills for or no days of supply overlapping between CYP3A4-mediated medication and the index date were classified as having no pDDI (ie, “non-pDDI group”) (Figure 1). Actual use of COVID-19 treatments, if any, was not captured. Three drug interaction resources were used to identify CYP3A4-mediated medications: University of Liverpool online drug interaction checker, Lexicomp online drug interaction checker, and the FDA Paxlovid fact sheet (Supplementary Table 1, available in online article).6,13,14 We assigned each medication to 1 of the 4 pDDI severity classes: contraindicated, major, moderate, and minor, based on information from the 3 drug interaction sources (Supplementary Table 2). Specifically, the contraindicated category included medications that are indicated as red in the Liverpool DDI checker, as “contraindicated and/or avoid concomitant use” in the FDA Paxlovid fact sheet, or as “X – avoid combination” from the Lexicomp drug database. The major category included medications that are not in the contraindicated category and are indicated as orange in the Liverpool DDI checker, as “dose adjustment may be needed” in the Paxlovid FDA fact sheet, or as “D – consider therapy modification” from the Lexicomp drug database. The moderate category included medications that are not in the contraindicated or major category and are indicated as yellow per the Liverpool DDI checker, as “monitoring needed/monitor for AEs” in the FDA Paxlovid fact sheet, or as “C – monitor therapy” from the Lexicomp drug database. The minor category included medications that are not in the contraindicated, major, or moderate levels as defined above. Medications were assigned to the highest of 3 severity groupings if there was disagreement between resources. In cases of polypharmacy, patients were assigned to the most severe pDDI category to which they were exposed.

FIGURE 1.

Sample Selection of Patients With COVID-19

STUDY MEASURES AND OUTCOMES

Baseline characteristics were summarized for the overall COVID-19 cohort and for the pDDI and non-pDDI groups separately. Patient characteristics included demographics (ie, age at index date, sex, race and ethnicity, and region), residence in a long-term care facility, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), and comorbidities/risk factors associated with progression to severe COVID-19.1,2 Comorbidities were confirmed if patients had at least 2 ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes for said comorbidities, at least 30 days apart in the baseline period (Supplementary Tables 3-5).

The prevalence of pDDIs was estimated for the overall COVID-19 cohort and by identified subgroups of interest as described below. Direct standardization to estimate the nationwide prevalence of patients at risk of pDDIs was performed using age-sex distribution estimates of the US COVID-19 population obtained by Leong et al.15 Subgroups included patients with specific demographics or 1 or more high-risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19 or pDDIs: older age (≥60 years), race, residence in long-term care facility, obesity, diabetes, immunocompromised status, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, chronic liver diseases, chronic kidney disease (stage 3-5), multimorbidity with 3 or more of the above conditions, and polypharmacy with CYP3A4-mediated medications. Polypharmacy was defined as having prescriptions of 5 or more CYP3A4 medications, each with at least 60 days of supply, during the baseline period.16 Estimates of subgroup prevalence were not standardized because of the lack of standard age-sex distributions within each subgroup. In a sensitivity analysis, we estimated pDDI prevalence assuming a hypothetical temporary discontinuation of statin treatments when patients were treated with ritonavir-containing medications, because statins were commonly used in the study population (23%).6,17-19

Means and SDs were calculated for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables. Statistical comparisons were conducted between the pDDI and non-pDDI groups using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for binary and categorical variables. No adjustments were made for these descriptive comparisons.

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

A total of 718,387 patients with a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis between January 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, met the study inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The mean age (SD) at index date was 56.5 (20.0) years. Approximately 46.8% of the study population were aged 60 years or older, 54.2% were female, and 36.9% of patients had at least 1 CCI comorbidity. Approximately 48.3% had at least 1 comorbidity/risk factor associated with progression to severe COVID-19, and 27.6% of patients had 2 or more high-risk comorbidities/risk factors. The most commonly observed high-risk comorbidities/risk factors were use of corticosteroids/immunosuppressive medications (35.4%), diabetes (19.4%), overweight and obesity (14.8%), mood disorders (11.7%), and disabilities (10.1%) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients With COVID-19

| All patients with COVID-19 (N=718,387) | pDDI group (n=432,707) | Non-pDDI group (n=285,680) | P value | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age at index date, years, mean±SD (median) | 56.5±20.0 (58.0) | 62.0±18.1 (65.2) | 48.3±19.9 (45.1) | <0.001 |

| Age group, years, n (%) | ||||

| 18-29 | 91,138 (12.7) | 29,752 (6.9) | 61,386 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| 30-49 | 182,483 (25.4) | 78,848 (18.2) | 103,635 (36.3) | |

| 50-59 | 108,210 (15.1) | 67,999 (15.7) | 40,211 (14.1) | |

| 60+ | 336,556 (46.8) | 256,108 (59.2) | 80,448 (28.2) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 389,312 (54.2) | 253,066 (58.5) | 136,246 (47.7) | <0.001 |

| Male | 328,839 (45.8) | 179,479 (41.5) | 149,360 (52.3) | |

| Unknown | 236 (0.0) | 162 (0.0) | 74 (0.0) | |

| Race and ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 21,152 (2.9) | 10,968 (2.5) | 10,184 (3.6) | <0.001 |

| Black/African American | 80,823 (11.3) | 53,136 (12.3) | 27,687 (9.7) | |

| Hispanic | 118,259 (16.5) | 68,978 (15.9) | 49,281 (17.3) | |

| White | 443,741 (61.8) | 269,700 (62.3) | 174,041 (60.9) | |

| Other/unknown | 54,412 (7.6) | 29,925 (6.9) | 24,487 (8.6) | |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||||

| Northeast | 98,816 (13.8) | 59,465 (13.7) | 39,351 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 160,751 (22.4) | 89,099 (20.6) | 71,652 (25.1) | |

| South | 334,669 (46.6) | 210,774 (48.7) | 123,895 (43.4) | |

| West | 117,329 (16.3) | 69,329 (16.0) | 48,000 (16.8) | |

| Other/unknown | 6,822 (0.9) | 4,040 (0.9) | 2,782 (1.0) | |

| Living in long-term care facilities,a n (%) | 85,435 (11.9) | 67,507 (15.6) | 17,928 (6.3) | <0.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| CCI, mean±SD (median) | 0.7±1.4 (0.0) | 1.0±1.6 (0.0) | 0.3±1.0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| ≥1 CCI comorbidity, n (%) | 265,119 (36.9) | 215,680 (49.8) | 49,439 (17.3) | <0.001 |

| Having ≥1 high-risk factors (comorbidity or age ≥60 years) for progression to severe COVID-19, n (%) | 445,134 (62.0%) | 330,740 (76.4%) | 114,394 (40.0%) | <0.001 |

| Comorbidity/risk factor associated with an increased risk for development of severe COVID-19, n (%) | 346,674 (48.3) | 268,615 (62.1) | 78,059 (27.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 high-risk comorbidity/risk factor | 148,298 (20.6) | 104,322 (24.1) | 43,976 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| 2 high-risk comorbidities/risk factors | 83,222 (11.6) | 66,892 (15.5) | 16,330 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| ≥3 high-risk comorbidities/risk factors (multimorbidity) | 115,154 (16.0) | 97,401 (22.5) | 17,753 (6.2) | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 47,432 (6.6) | 36,201 (8.4) | 11,231 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease (stage 3+) | 46,265 (6.4) | 38,791 (9.0) | 7,474 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | ||||

| Interstitial lung disease | 3,306 (0.5) | 2,778 (0.6) | 528 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 3,300 (0.5) | 2,708 (0.6) | 592 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 6,097 (0.8) | 5,094 (1.2) | 1,003 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| COPD and bronchiectasis | 46,828 (6.5) | 39,938 (9.2) | 6,890 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver diseases | ||||

| Cirrhosis | 3,714 (0.5) | 3,099 (0.7) | 615 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | 6,387 (0.9) | 5,163 (1.2) | 1,224 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 966 (0.1) | 760 (0.2) | 206 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 333 (0.0) | 273 (0.1) | 60 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | ||||

| Heart failure | 41,265 (5.7) | 34,501 (8.0) | 6,764 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 64,210 (8.9) | 53,739 (12.4) | 10,471 (3.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathies | 8,959 (1.2) | 7,594 (1.8) | 1,365 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 56 (0.0) | 51 (0.0) | 5 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, type 1 and type 2 | 139,317 (19.4) | 116,742 (27.0) | 22,575 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Disabilitiesb | 72,497 (10.1) | 55,056 (12.7) | 17,441 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| HIV | 2,071 (0.3) | 1,889 (0.4) | 182 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Immune deficiencies | 2,890 (0.4) | 2,393 (0.6) | 497 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Mental health disorders | ||||

| Mood disorders, including depression | 83,949 (11.7) | 69,324 (16.0) | 14,625 (5.1) | <0.001 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorders | 5,075 (0.7) | 4,621 (1.1) | 454 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Neurological conditions | ||||

| Dementia | 35,656 (5.0) | 28,257 (6.5) | 7,399 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Alzheimer disease | 12,871 (1.8) | 10,198 (2.4) | 2,673 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Overweight and obesity | 106,319 (14.8) | 84,763 (19.6) | 21,556 (7.5) | <0.001 |

| Pregnancy and recent pregnancy | 8,301 (1.2) | 2,611 (0.6) | 5,690 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| Smoking, current and former | 17,603 (2.5) | 14,148 (3.3) | 3,455 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Sickle cell disease | 352 (0.0) | 261 (0.1) | 91 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Solid organ or blood stem cell transplantation | 2,719 (0.4) | 2,382 (0.6) | 337 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Substance usec | 7,746 (1.1) | 6,687 (1.5) | 1,059 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Thalassemia | 317 (0.0) | 237 (0.1) | 80 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Tuberculosis | 71 (0.0) | 52 (0.0) | 19 (0.0) | 0.025 |

| Use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications | 254,171 (35.4) | 202,943 (46.9) | 51,228 (17.9) | <0.001 |

a Long-term care facilities include skilled nursing facility, nursing facility, custodial care facility, intermediate care facility, and assisted living facility. Patients who had 1 or more visits in long-term care facilities during baseline period were identified as living in long-term care facilities.

b Disabilities were taken from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention list of high-risk factors for severe COVID-19, including ADHD, autism, birth defects, blindness, cerebral palsy, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disorder, chromosomal disorder, chromosomal deletion, cognitive impairment, deafness, Down syndrome, Fahr syndrome, fragile X syndrome, Gaucher disease, hydrocephalus, intellectual impairment, learning disability, Leigh syndrome, Leber hereditary or automanual dominant optic neuropathy, MELAS syndrome, myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers, mobility disability, movement disorders, multiple disability, myotonic dystrophy, neuropathy, ataxia, and retinitis pigmentosa, neurodevelopmental disorders, neuromyelitis optical spectrum disorder, primary mitochondrial myopathy, profound intellectual impairment, senior-Loken syndrome, perinatal spastic hemiparesis, spinal cord injury, spina bifida and other nervous system anomalies, progressive supranuclear palsy, traumatic brain injury, Tourette syndrome, and wheelchair use.

c Substance use does not include cigarette smoking.

ADHD=attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; CCI=Charlson comorbidity index; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; MELAS=mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes; pDDI=potential drug-drug interaction.

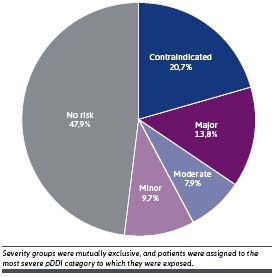

PREVALENCE OF pDDIs

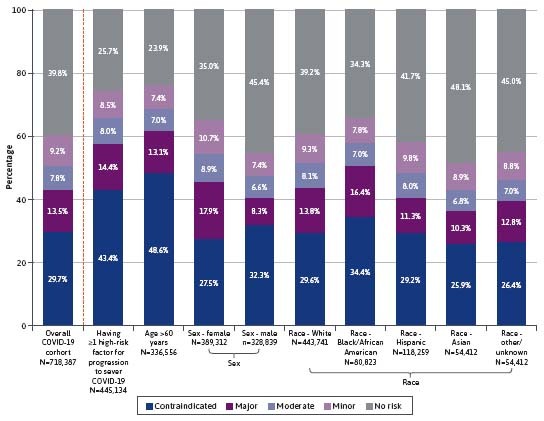

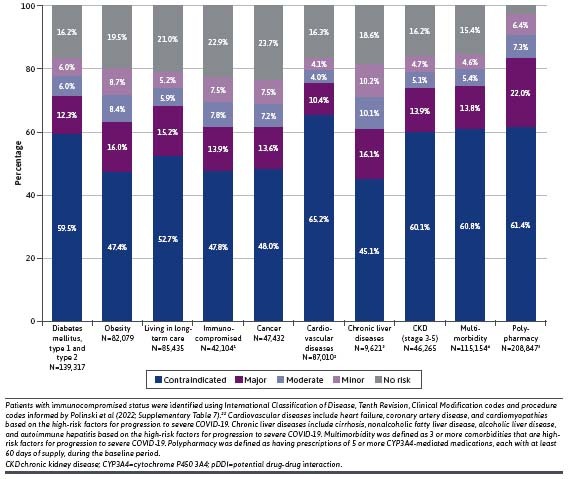

The age-sex standardized national prevalence of pDDIs of any severity was estimated at 52.2%. Approximately 34.5% were at risk of contraindicated or major pDDIs (Figure 2). The unadjusted prevalence of pDDIs of any severity in the study population was 60.2%, whereas 43.2% had contraindicated or major pDDIs (Figure 3). The most prevalent contraindicated and major pDDI treatments observed in the entire cohort are described in Supplementary Table 6. The prevalence of contraindicated/major pDDI was 57.8% among patients with 1 or more risk factors for progression to severe COVID-19 or pDDIs. The prevalence was 61.7% among patients aged 60 years or older, and it was slightly higher among female patients (45.4%) than male patients (40.6%). Black/African American patients had the highest prevalence across all races and ethnicity groups (50.8%). For patients with chronic comorbidities, the prevalence was also higher than that of the overall population (71.8% among patients with diabetes, 63.4% among patients with obesity, 61.7% among immunocompromised patients, 61.6% among patients with cancer, 75.6% among patients with cardiovascular diseases, 61.2% among patients with chronic liver diseases, 74.0% among patients with stage 3-5 chronic kidney disease, 74.6% among patients with multimorbidity, and 83.4% among patients with polypharmacy) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Standardized National Prevalence of pDDIs by Severity Among All Patients With COVID-19

FIGURE 3.

Prevalence of Patients at Risk of pDDIs—Overall COVID-19 Cohort and by Selected Subgroup

CHARACTERISTICS OF PATIENTS WITH PDDIS

Compared with the non-pDDI group, patients with pDDIs were significantly older (62.0 vs 48.3 years), were more likely to be female (58.5% vs 47.7%), were more likely to reside in a long-term care facility (15.6% vs 6.3%), had higher CCI scores (1.0 vs 0.3), and were more likely to have 1 or more high-risk factors associated with an increased risk of progression to severe COVID-19 (76.4% vs 40.0%; all P<0.001). The pDDI group also had substantially higher rates of underlying comorbidities/risk factors (22.5% vs 6.2%), including diabetes (27.0% vs 7.9%), overweight and obesity (19.6% vs 7.5%), mood disorders (16.0% vs 5.1%), intellectual and developmental disabilities (12.7% vs 6.1%), and use of corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive medications during the baseline period (46.9% vs 17.9%; all P<0.001) (Table 1).

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

Findings in the sensitivity analysis excluding statins from the list of CYP3A4-mediated medications were similar to findings in the main analysis. Only 2.6% (18,610) of patients used statins as their only prescription-filled medication. Most patients (88.8%) using statins also filled prescriptions for nonstatin medications that put them at significant risk of pDDIs. In the sensitivity analysis, 57.6% (vs 60.2% in the primary analysis) of patients were observed to be at risk of pDDIs of any severity with nonstatin drugs, with 16.3% and 19.2% of patients at risk of pDDIs of contraindicated and major severity, respectively. Among patients with at least 1 risk factor for progression to severe COVID-19, 70.9% were observed to be at risk of pDDIs of any severity with nonstatin drugs (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Sensitivity Analysis: Prevalence of Patients at Risk of pDDIs Excluding Statins

| Patients at risk (n) | Prevalence (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Overall COVID-19 cohort (n=718,387) | ||

| pDDI excluding statins | 414,097 | 57.6 |

| Contraindicated | 117,258 | 16.3 |

| Major | 137,944 | 19.2 |

| Moderate | 76,841 | 10.7 |

| Minor | 82,054 | 11.4 |

| Having ≥1 risk factor for progression to severe COVID-19/pDDIs (n=445,134) | ||

| pDDI excluding statins | 315,663 | 70.9 |

| Contraindicated | 106,362 | 23.9 |

| Major | 102,603 | 23.0 |

| Moderate | 54,281 | 12.2 |

| Minor | 52,417 | 11.8 |

pDDI=potential drug-drug interaction.

Discussion

In this observational study examining a large cohort of patients with COVID-19 in a nationwide commercial claims database, we observed that approximately 40% of all patients with COVID-19 would be at risk of serious pDDIs if treated with a ritonavir-based COVID-19 therapy. Our findings remained robust after excluding statins, which, per FDA guidelines, are recommended to be discontinued while treating patients with a ritonavir-based COVID-19 therapy.6 In certain patient subgroups, such as older patients and patients with multiple morbidities, very high prevalence of major or contraindicated pDDIs was observed. Our findings underscore the need for DDI assessments in COVID-19 treatment decision-making, especially in high-risk patient groups. Future research may be conducted to compare the prevalence rates of pDDIs between these high-risk subgroups.

The literature describing the risk of pDDIs associated with approved COVID-19 treatments continues to evolve. Previous studies evaluating pDDIs associated with COVID-19 therapies have typically been limited to case reports and case series or studies with small sample sizes and specific patient subpopulations with COVID-19.11,20,21 Our study examined a nationally representative commercial claims database, which allowed for evaluation of a large sample, as well as high-risk patient subgroups. Furthermore, we used multiple well-established resources to generate a comprehensive list of CYP3A4-mediated medications,6,13,14 ensuring investigation of a wide array of medications and their likely pDDI severities.

DDI management strategies have been recommended by various US health care stakeholders, including the FDA and NIH COVID-19 guideline panel.12 Strategies include temporary withholding or dose adjustment of concomitant medications with known DDI potential, using alternative concomitant medications, monitoring patients for DDI-associated adverse events, or using alternative COVID-19 therapies.12 Some of these strategies (notably, temporary withholding and monitoring) may be difficult to implement in cases that care is multifaceted or fragmented or a full picture of patients’ medication history is unavailable. Also, although DDI management strategies for individual medications may be straightforward, patients may be taking multiple medications with DDI potential, introducing additional complexity to clinical management. For example, we observed that approximately 30% of the study population had polypharmacy with multiple CYP3A4-mediated medications, further exacerbating the challenges associated with current DDI management strategies.

LIMITATIONS

Findings from this study may only be generalizable to patients with COVID-19 who have consistent access to health care and who receive health care coverage through commercial plans. Similarly, because the study population comprised commercially insured individuals who tend to be younger and use less chronic medications, the pDDI prevalence rates may be lower compared with those of patients who are covered under public insurance plans such as Medicare. Claims data are also subject to coding errors, and patients who fill prescriptions may not always use them.

Conclusions

This large, observational study demonstrated that 34.5% of patients with COVID-19 in the United States were at risk of contraindicated or major pDDIs if treated with ritonavircontaining COVID-19 therapy. These findings emphasize the need for clinicians to carefully review patients’ medications prior to prescribing and dispensing COVID-19 therapy. DDI management strategies such as monitoring for potential adverse reactions, dose adjustment, and temporary withholding of concomitant medication may not always be possible in patients requiring complex care or when DDI risk outweighs potential benefits. Therefore, these patients may require alternative outpatient COVID-19 treatment options.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support was provided by a professional medical writer, Christine Tam, MWC, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: People with certain medical conditions. Accessed February 25, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Underlying medical conditions associated with higher risk for severe COVID-19: Information for healthcare professionals. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-care/underlyingconditions.html#accordion-1-card-1 [PubMed]

- 3.Hodge C, Marra F, Marzolini C, et al. Drug interactions: A review of the unseen danger of experimental COVID-19 therapies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020;75(12):3417-24. doi:10.1093/jac/dkaa340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes additional oral antiviral for treatment of COVID-19 in certain adults. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-oral-antiviral-treatment-covid-19-certain. [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA authorizes first oral antiviral for treatment of COVID-19. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-first-oral-antiviral-treatment-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fact sheet for healthcare providers: Emergency use authorization for paxlovid. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/media/155050/download [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandariz-Nunez D, Correas-Sanahuja M, Guarc E, Picon R, Garcia B, Gil R. Potential drug-drug interactions in COVID 19 patients in treatment with lopinavir/ritonavir. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;155(7):281-7. doi:10.1016/j.medcle.2020.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantudo-Cuenca M, Gutierrez-Pizarraya A, Pinilla-Fernandez A, et al. Drug–drug interactions between treatment specific pharmacotherapy and concomitant medication in patients with COVID-19 in the first wave in Spain. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):12414. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-91953-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conti V, Sellitto C, Torsiello M, et al. Identification of drug interaction adverse events in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(4):e227970. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.7970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X, Yang Y, Liu L, et al. Effect of combination antiviral therapy on hematological profiles in 151 adults hospitalized with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Pharmacol Res. 2020;160:105036. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Lopez-de-Castro N, Samartin-Ucha M, Paradela-Carreiro A, et al. Real-world prevalence and consequences of potential drug-drug interactions in the first-wave COVID-19 treatments. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2021;46(3):724-30. doi:10.1111/jcpt.13337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institutes of Health. Drug-drug interactions between ritonavir-boosted Nirmatrelvir (Paxlovid) and concomitant medications. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/therapies/antiviral-therapy/ritonavir-boosted-nirmatrelvir--paxlovid-/paxlovid-drug-drug-interactions/

- 13.University of Liverpool. COVID-19 drug interactions. Accessed February 27, 2022. https://www.covid19-druginteractions.org/checker

- 14.Kluwer Wolters. Lexicomp: Evidence-based drug treatment information. Accessed March 17, 2022. https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/lexicomp

- 15.Leong R, Lee T-SJ, Chen Z, et al. Global temporal patterns of age group and sex distributions of COVID-19. Infect Dis Rep. 2021;13(2):582-96. doi:10.3390/idr13020054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230. doi:10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: Important safety label changes to cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. Accessed July 21, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-important-safety-label-changes-cholesterol-lowering-statin-drugs [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Ploeg MA, Floriani C, Achterberg WP, et al. Recommendations for (discontinuation of) statin treatment in older adults: Review of guidelines. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(2):417-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.16219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: Interactions between certain HIV or hepatitis C drugs and cholesterol-lowering statin drugs can increase the risk of muscle injury. Accessed June 28, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-interactions-between-certain-hiv-or-hepatitis-c-drugs-and-cholesterol [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salerno DM, Jennings DL, Lange NW, et al. Early clinical experience with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 in solid organ transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(8):2083-8. doi:10.1111/ajt.17027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang AX, Koff A, Hao D, Tuznik NM, Huang Y. Effect of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir on calcineurin inhibitor levels: Early experience in four SARS-CoV-2 infected kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(8):2117-9. doi:10.1111/ajt.16997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polinski JM, Weckstein AR, Batech M, et al. Durability of the single-dose Ad26.COV2.S vaccine in the prevention of COVID-19 infections and hospitalizations in the US before and during the delta variant surge. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e222959. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]