Abstract

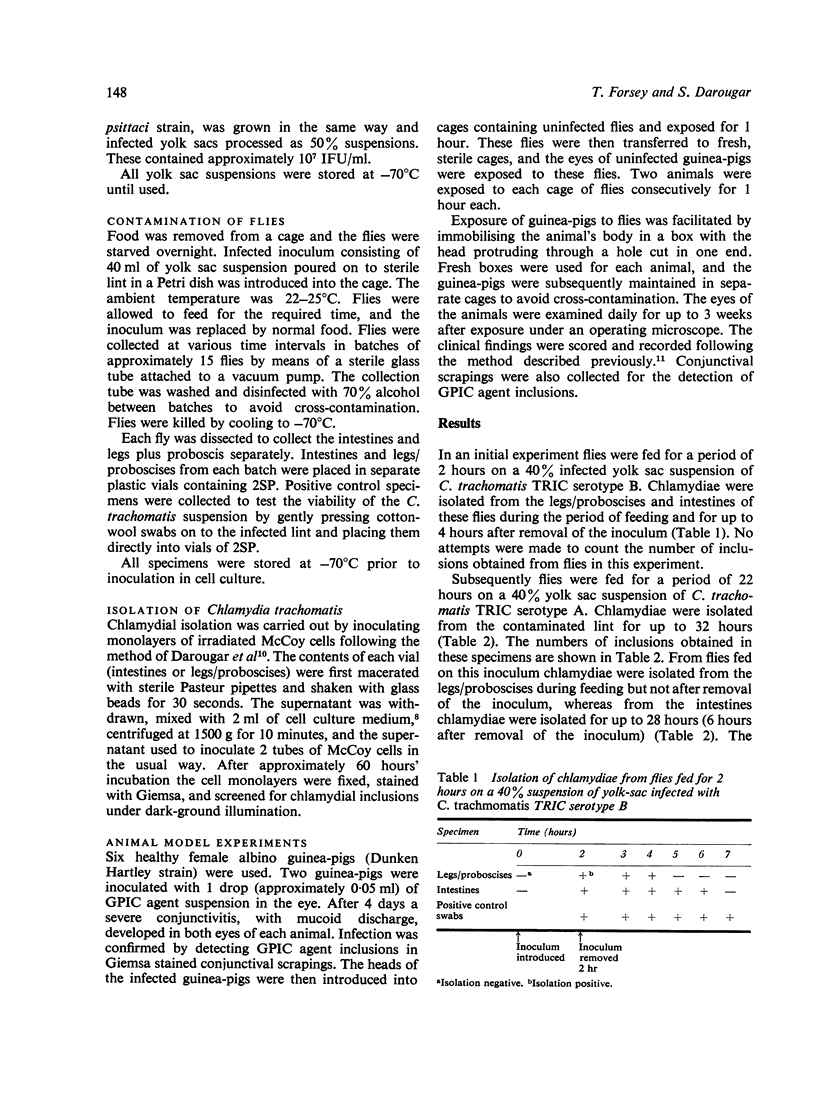

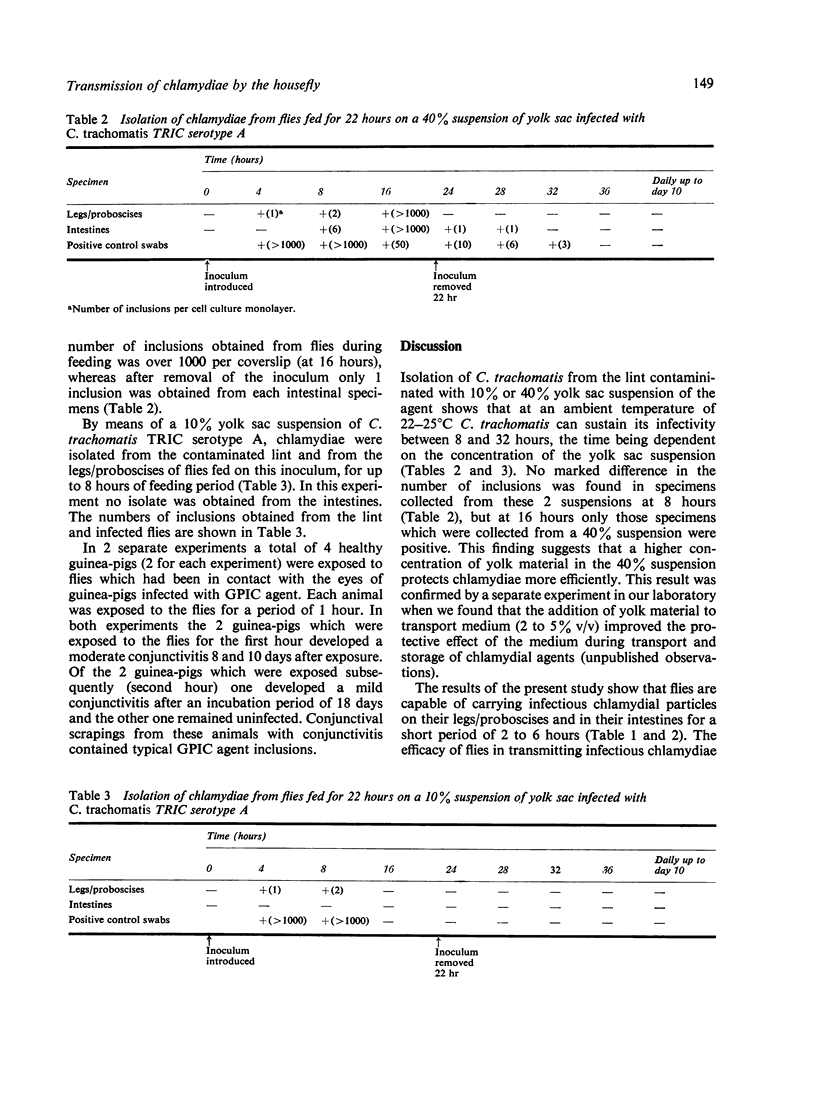

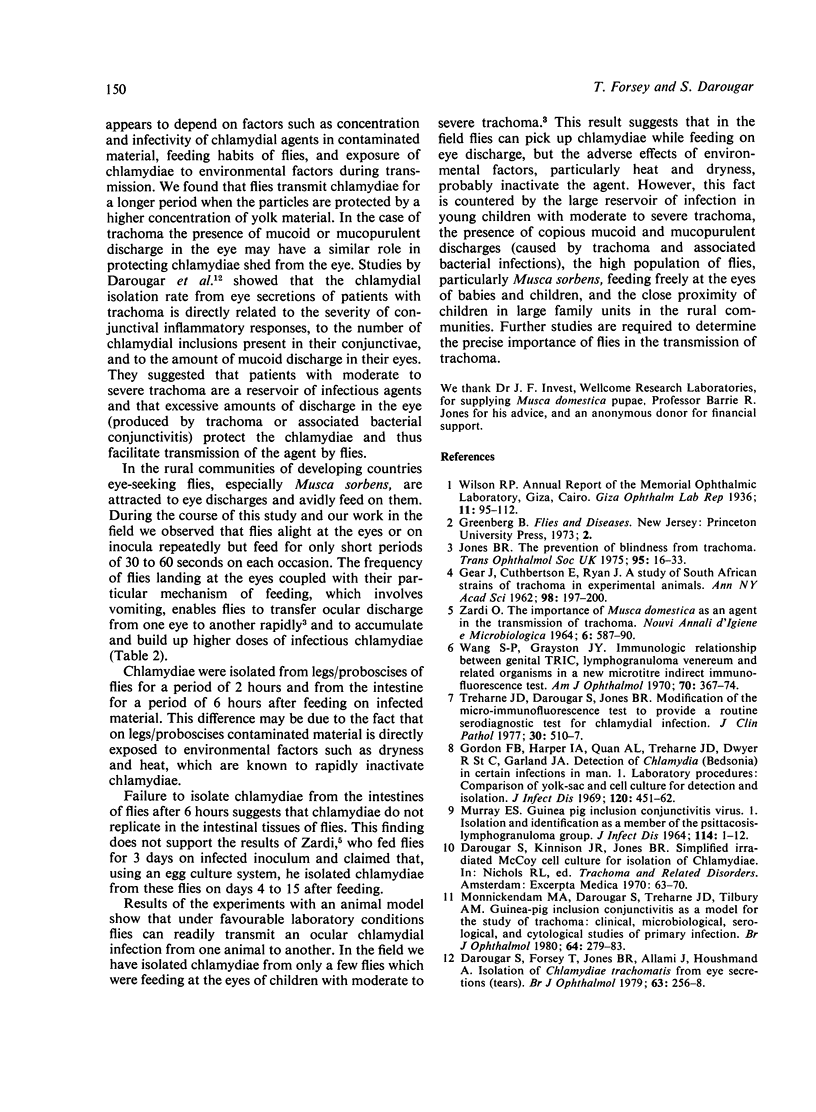

The ability of the housefly to carry viable Chlamydia trachomatis and to transmit a chlamydial ocular infection was studied under laboratory conditions. After feeding flies (Musca domestica) on suspensions of egg yolk sac infected with C. trachomatis serotypes A or B (responsible for hyperendemic trachoma) the agents were reisolated from flies' intestines for up to 6 hours and from their legs and/or proboscises for up to 2 hours. It was found that the viability of chlamydiae is dependent on the protective effect of yolk concentration in the original inoculum. Results of experiments with guinea-pig inclusion conjunctivitis as an animal model show that under laboratory conditions flies can readily transmit this chlamydial ocular infection from one animal to another. These results suggest that under field conditions flies can play an important role in the transmission of trachoma, particularly in areas with favourable conditions such as a large reservoir of infection among children with severe trachoma, copious eye discharge caused by trachoma and associated bacterial infections, a large fly population, and close proximity of children in large family groups.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Darougar S., Forsey T., Jones B. R., Allami J., Houshmand A. Isolation of Chlamydia trachomatis from eye secretion (tears). Br J Ophthalmol. 1979 Apr;63(4):256–258. doi: 10.1136/bjo.63.4.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEAR J., CUTHBERTSON E., RYAN J. A study of South African strains of trachoma virus in experimental animals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1962 Mar 5;98:197–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb30544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon F. B., Harper I. A., Quan A. L., Treharne J. D., Dwyer R. S., Garland J. A. Detection of Chlamydia (Bedsonia) in certain infections of man. I. Laboratory procedures: comparison of yolk sac and cell culture for detection and isolation. J Infect Dis. 1969 Oct;120(4):451–462. doi: 10.1093/infdis/120.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B. R. The prevention of blindness from trachoma. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1975 Apr;95(1):16–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY E. S. GUINEA PIG INCLUSION CONJUNCTIVITIS VIRUS. I. ISOLATION AND IDENTIFICATION AS A MEMBER OF THE PSITTACOSIS-LYMPHOGRANULOMA-TRACHOMA GROUP. J Infect Dis. 1964 Feb;114:1–12. doi: 10.1093/infdis/114.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnickendam M. A., Darougar S., Treharne J. D., Tilbury A. M. Guinea-pig inclusion conjunctivitis as a model for the study of trachoma: clinical, microbiological, serological, and cytological studies of primary infection. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980 Apr;64(4):279–283. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.4.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treharne J. D., Darougar S., Jones B. R. Modification of the microimmunofluorescence test to provide a routine serodiagnostic test for chlamydial infection. J Clin Pathol. 1977 Jun;30(6):510–517. doi: 10.1136/jcp.30.6.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. P., Grayston J. T. Immunologic relationship between genital TRIC, lymphogranuloma venereum, and related organisms in a new microtiter indirect immunofluorescence test. Am J Ophthalmol. 1970 Sep;70(3):367–374. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)90096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]