Abstract

This study assesses the frequency of continuation patents on brand-name drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration from 2000 to 2015.

Brand-name pharmaceutical manufacturers often sustain high prices in the US by obtaining patents that delay generic competition. Patents may be obtained on active ingredients and “secondary” features of drugs such as new formulations and methods of use.1,2 One legal strategy to obtain large numbers of secondary patents is via a special type of application to the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), called a continuation, in which a patent holder adds new applications to a prior submission by offering minor clarifications or additions without substantial change to the underlying invention. Continuation patents can deter competition by increasing uncertainty for generic manufacturers, since they must avoid infringing (or must challenge) evolving patent claims on drugs.

Members of Congress have called on the USPTO to address the excessive use of continuation patents.3,4 We examined the frequency of continuation patents on brand-name drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) from 2000 to 2015.

Methods

We identified newly approved drugs using the Drugs@FDA database.5 We excluded drugs approved after 2015, since manufacturers often add continuation patents several years after FDA approval, and we excluded continuation-in-part and divisional patents because they may not have identical specifications. We extracted patents listed on these drugs in the FDA’s Approved Products With Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations (Orange Book) from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2021, and categorized each patent as original or continuation using the Google Patents Public Data Sets on Google BigQuery. We calculated the ratio of original and continuation patents per brand-name drug approval during each year. A similar analysis was conducted for litigated patents, based on litigation brought by either the drug manufacturer or generic competitor. Litigated patents were identified using Lex Machina, a commercial database covering 2000-2022.

Analyses were descriptive and completed in Excel version 16.

Results

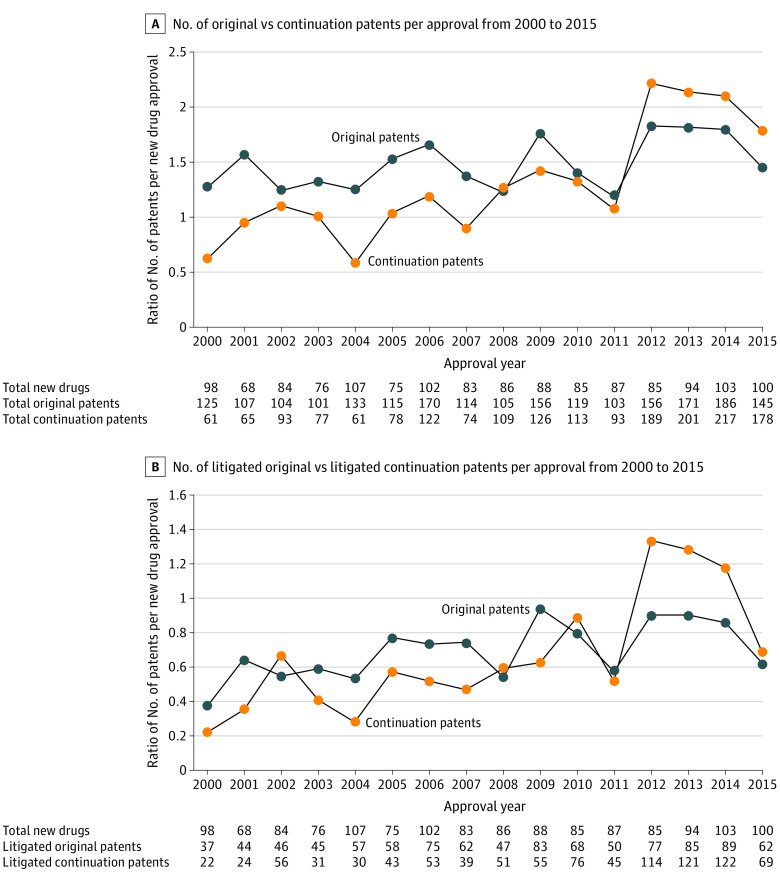

From 2000 to 2015, the FDA approved 1421 new brand-name drugs. Manufacturers listed with the FDA 3967 distinct patents on these drugs through 2021 (2110 [53%] original; 1857 [47%] continuation). The ratio of the number of FDA-listed patents per drug increased from 1.9 for those approved in 2000 to 3.2 for those approved in 2015 (68% relative increase). While the ratio of the number of original patents per approval increased by 15% from 1.3 for drugs approved in 2000 to 1.5 for drugs approved in 2015, the ratio of continuation patents increased 200% from 0.6 for drugs approved in 2000 to 1.8 for drugs approved in 2015 (Figure, A).

Figure. Growth in the Number of Original and Continuation Patents per New Drug Approval From 2000 to 2015.

There were 1936 litigated patents (985 [51%] original; 951 [49%] continuation). While the ratio of the number of litigated original patents per approval increased by 63% from 0.38 for drugs approved in 2000 to 0.62 for drugs approved in 2015, the ratio of litigated continuation patents increased 213% from 0.22 for drugs approved in 2000 to 0.69 for drugs approved in 2015 (Figure, B).

Discussion

Brand-name drug manufacturers listed with the FDA an increasing number of continuation patents on drugs approved from 2000 to 2015. More continuation patents mean that generic firms seeking to challenge existing protections on brand-name drugs must contest and potentially litigate more patents. Continuation patents are typically invalidated at a higher rate than patents on active ingredients.2 However, lawsuits brought by brand-name firms on patents listed with the FDA can earn 30-month stays on generic drug approval even if these lawsuits eventually fail. Study limitations include that the frequency of successful challenges on litigated continuation patents was not examined.

These findings suggest that continuation patents are becoming increasingly common in drug patent thickets, likely delaying or deterring generic competition,2,5 and thus potentially contributing to delays in patient access to generic medications and increases in health care spending.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Tu SS, Sarpatwari A. A “method of use” to prevent generic and biosimilar market entry. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(6):483-485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2216020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tu SS, Lemley MA. What litigators can teach the Patent Office about pharmaceutical patents. Wash Law Rev. 2022;99:1673-1731. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3903513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.March 24, 2023, letter to Kathi Vidal from Jodey Arrington (R, Texas), Michael Burgess (R, Texas), Darrell Issa (R, California), Lloyd Doggett (D, Texas), and Ann Kuster (D, New Hampshire). Accessed May 16, 2023. https://arrington.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=956

- 4.April 26, 2023, letter to Kathi Vidal from Elizabeth Warren (D, Massachusetts) and Pramila Jayapal (D, Washington). Accessed May 16, 2023. https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2023.04.26%20Letter%20to%20USPTO%20re%20patent%20abuses1.pdf

- 5.Google BigQuery. Accessed May 21, 2023. https://cloud.google.com/bigquery/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Sharing Statement