Abstract

Within the Criminal Justice System, using animals for therapeutic or rehabilitative purposes has garnered momentum and is extensively researched. By contrast, the evidence concerning the impact of farm animal work, either on prison farms or social farms for community sanctions, is less well understood. This review sought to explore the evidence that exists in relation to four areas: (1) farm animals and their contribution to rehabilitation from offending; (2) any indicated mechanisms of change; (3) the development of a human—food/production animal bond, and (4) the experiences of forensic service users working with dairy cattle. Fourteen articles were included in the review. Good quality research on the impact of working with farm animals and specifically dairy cattle, with adult offenders, was very limited. However, some studies suggested that the rehabilitative potential of farm animals with offenders should not be summarily dismissed but researched further to firmly establish impact.

Keywords: farm animals, offenders, prison farms, dairy cattle, rehabilitation

Introduction

There is compelling evidence that engaging with nature is beneficial for humans. Described in Wilson’s (1984) Biophilia Hypothesis as an “innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes” (p.1), human beings have a reliance on, and emotional connection with, nature for survival and reproduction. Nature is also deemed restorative (Kaplan, 1995) and its importance underpins the movement known as Green Care. This term encompasses a number of different activities designed to address a variety of social needs through direct interactions with natural environments (Moriggi et al., 2020). Whilst not used consistently, the Green Care concept commonly refers to nature-based activities undertaken for a variety of different purposes to benefit the recipients, for example, to improve physical and psychological wellbeing and to increase social inclusion. Green Care initiatives include care farming (also known as social farming), therapeutic horticulture, nature-based recreation and therapy, and interventions that involve animals.

Within the Criminal Justice System, the use of animals in custodial and community settings for people with offending histories (hereafter also referred to as forensic service users) appears to have garnered momentum over the last two decades, alongside an explosion of other Green Care activities (e.g., horticulture programs in prisons, Lee et al., 2021). Animal programs with incarcerated populations have been designed to address a variety of aims including: reduction of post release recidivism (Cooke et al., 2021); improved custodial behavior (van Wormer et al., 2017); increased psychological wellbeing (Kunz-Lomelin & Nordberg, 2020); achievement of vocational qualifications and therefore increased employability (Mims et al., 2017), and a calming influence on the overall correctional environment (Cooke & Farrington, 2015).

Furst (2006) described programs where individuals with offending histories are working with or training animals (as opposed to an animal being present primarily for a therapeutic aim) as Prison Animal Programs (PAPs). In a survey of 36 US states, Furst (2006) identified eight different types of PAPs: the use of companion animals (i.e., an animal introduced to an individual to provide short-term benefits while they are together); wildlife rehabilitation; pet adoption; service animal socialization; vocational achievement; community service (care and training of animals); multimodal (combination of vocational and community service), and livestock care programs focusing on farm animal care and husbandry. Across these different categories there is research on programs with dogs (Cooke & Farrington, 2016; Flynn et al. 2020; Villafaina-Dominguez et al., 2020) and horses (Bachi, 2013; Morgan, 2020) and their impact on rehabilitation from offending. By contrast, the livestock care and farm work subset of PAPs does not appear to have been subject to rigorous scrutiny, despite being the fourth most common type identified by Furst (2006) and one which she suggested should be considered as a distinct type of PAP. In particular, Furst queried whether prisoners working with farm animals could develop empathetic relationships in the same way observed in PAPs involving companion animals. The impact of working with farm animals on people with offending histories is the topic under study here, with a particular focus on work with cows.

A preliminary search for existing reviews on farm animals and people with offending histories was conducted. No reviews were identified and any relevant literature that was indexed was within the context of social farms only (e.g., Artz & Davis, 2017). These did not include prison farms and did not focus specifically on the population of interest for this review, namely adults with criminal convictions, nor the specific concept of farm animal work and offender rehabilitation. Furthermore, whilst cows were the second most common animal involved in the PAPs reviewed in Furst’s study, there is a notable deficit in the literature focused specifically on forensic service users working with cows.

Given the paucity of literature on farm animal programs for people with offending histories, this scoping review is concerned with the following questions: (1) Does evidence exist to suggest that farm animal work can contribute to the rehabilitation of adults with criminal convictions? (2) If so, which mechanisms for change are indicated and might be worthy of further exploration? (3) Is there evidence that a human-animal bond can be developed with a food or production animal? (4) What evidence exists about the experiences of forensic service users working with dairy cattle in particular?

Method

Peters et al. (2020) highlighted the value that a scoping review can bring to a field of research where it is not yet possible to ask precise questions about the effectiveness of an intervention and when there are clear gaps in knowledge about a particular topic. The scoping review for this study followed the protocol proposed by Peters et al. (2020) contained in the latest version of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis (Aromataris & Munn, 2020). This protocol is consistent with Tricco et al.’s (2018) PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR). The overarching goal was to map and evaluate the research literature on farm animal work and its contribution to rehabilitation from offending in adults.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The population of interest (participants) is adults who have acquired a formal criminal conviction and consequently received either a community or custodial sanction. For the purpose of this review and according to legal classification, adults are individuals over 18 years of age. The concept being explored within the scoping review is farm animal work and its potential for rehabilitation from offending. Farm animal work refers to animal husbandry tasks with food or production animals, for example, cows, goats, sheep, pigs, and chickens, as well as those used for this purpose in other countries such as rabbits, buffalo, and ostrich. However, fish farms are excluded from the scoping review as this would be classed as aquafarming not traditional livestock farming. The context to the review is on research that has been conducted on prison farms (including those run by both private sector and public sector prisons) and community social farms (a farm using farming practices in a structured, supervised way for a specific purpose, such as rehabilitation and education). Within this context, dairy farms are of particular interest. Any PAP that is established primarily for therapeutic intent (whether within a formalized intervention or not) is also excluded.

The types of sources of evidence included in the scoping review were peer reviewed journal articles published in English over a 15 year period between 2006 (when Furst’s study on PAPs was published and when she recommended that livestock care programs should be viewed as a unique subset of PAPs) and 2021. The topic of interest is very narrow and, as such, there was a need to ensure that relevant evidence was not omitted. The review therefore considered a broad range of literature including primary research studies using quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods design, textual papers and reviews (both published and unpublished) and gray literature. The searches were conducted between 7th July and 29th July 2021.

Search Strategy

The search strategy followed the recommendations from Peters et al. (2020) and Tricco et al. (2018). Peer reviewed publications were captured from the following databases: SCOPUS, Psychinfo, Medline, and Criminal Justice Database (Proquest Central). Gray literature was accessed via Google Scholar, the Research and Statistics webpage of published research from UK Government agencies, and email communication designed to capture any additional relevant research from Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service. The Human Animal Bond Research Institute (HABRI) Central on-line database was hand searched, along with the Journal of Correctional Education and reference lists were reviewed for any additional papers of relevance. The searching for this scoping review was an iterative process and as such, two searches were performed for each source, the second search removing less helpful terms and introducing terms of more potential utility. Table 1 demonstrates the complete search strategy for one database and includes the Boolean operators and terms that were removed for Search 2 as indicated by *. Limiters were put on the searches to only include studies written in English.

Table 1.

Search Strategy for Criminal Justice Database.

| Search | Concept (OR) AND | Context (OR) AND | Population (OR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Rehabilitation | Prison | Prisoner |

| Desistance | Penitentiary | Criminal | |

| Recidivism | Jail/gaol | Offender | |

| Cessation* | Institute* | Inmate | |

| Offending | Facility* | Convict* | |

| Reformation* | Probation | Felon* | |

| Recovery* | Parole | Forensic service user | |

| Penal | AND | ||

| AND | Bovine | ||

| Prison farm | Cattle | ||

| Care farm | Cows | ||

| Social farm | Dairy | ||

| Smallholding | Milk* | ||

| Farmstead | Herd* | ||

| Ranch* | Ruminant* | ||

| Livestock | Calves* | ||

| Agriculture* | Kine* | ||

| Production animal | |||

| Food animal | |||

| S2 | “Prison farm animal program” | ||

| “Prison dairy animal program” | |||

| “Correctional agriculture” |

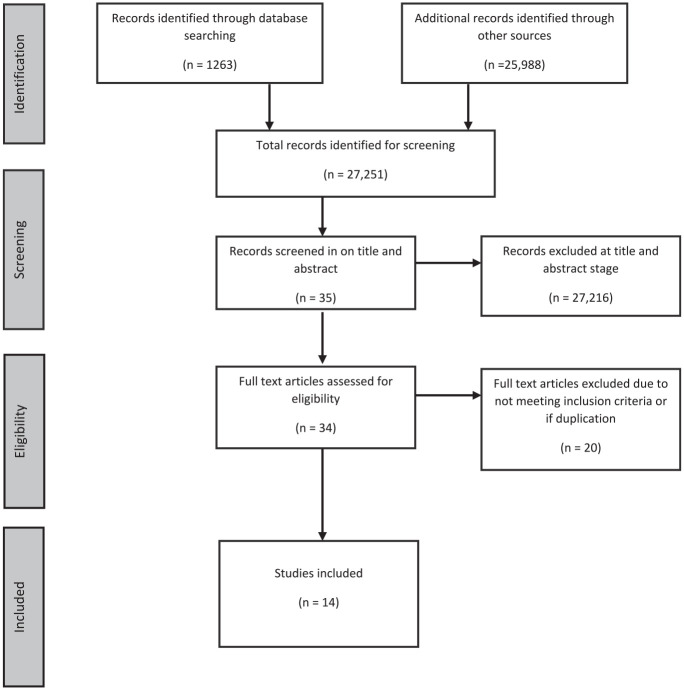

Evidence Screening and Selection

The searches identified 27,251 records (see Figure 1 flow diagram). Following the Peters et al. (2020) guidance, a minimum of two reviewers (LP and JM) undertook the screening and selection stage of the protocol, with a third reviewer (CG) available to resolve any disagreements. The search results were initially reviewed according to title and abstract, with 35 screened in records transferred to and managed within the Endnote V.20 reference software. The selected articles were then subject to full text retrieval and review which resulted in the loss of one further record which did not focus on the population of interest. A further 20 sources were removed in the de-duplication process and as a result of records not meeting the inclusion criteria, leaving 14 studies for review. There were no disagreements between the two reviewers which necessitated the contribution of the third reviewer.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the scoping review study selection process (adapted from Moher et al., 2009).

Data Extraction

During the data extraction process, the authors sought to understand the purpose of the article, country of origination, the method employed (if appropriate) and to what extent the article addressed the four scoping review questions. A data extraction template was developed to capture this information, minimize bias and was reviewed regularly by the first two authors to maintain its utility and to meet the objectives of the scoping review.

Results and Discussion

Table 2 summarizes the 14 records that were included in the scoping review. The articles originated from the UK (n = 5), the USA (n = 4), Canada (n = 2), India (n = 1), Kenya, (n = 1) and Nigeria (n = 1). Nine of the studies were published in peer reviewed journals (most of which were rooted in criminal justice disciplines) with the remaining records coming from magazine publications (n = 2) and reports affiliated with specific organizations (n = 3).

Table 2.

Description of Included Studies.

| Authors | Population | Context | Aim/Purpose | Research design (if appropriate) | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elsey et al. (2018) | Probation Service Users on Community Orders (CO’s) | Three care farms (CF) in the community and Comparator CO’s | Understand the impact of CFs & feasibility study on cost effectiveness of CFs on quality of life and future offending | Mixed methods Quantitative—(n = 134 adults) pilot study using Clinical Outcome in Routine Evaluation–Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), reconviction data from PNC record, OGRS score and measures of MH, lifestyle and connectedness to nature Qualitative—perceptions of probation services (n = 5), care farmers (n = 6), and offenders (n = 8). Systematic Review—effectiveness and possible change mechanism for any CF client group |

Quantitative—CF participants were more likely to be male, smokers and substance users and had a higher risk of reoffending. Statistical analysis allowed comparison of different sites with participants with different characteristics. Qualitative—Some Probation Services used CFs as rehabilitation and others emphasized them as punishment. Systematic Review—Four logic models for (1) all service user groups (2) those with MH & substance misuse (3) disaffected youth (4) people with learning disability. Models consisted of five theoretical concepts and 15 categories of mechanisms for impact of CFs. CF’s found to work in different ways according to different needs. No evidence to indicate they improve quality of life, limited evidence to suggest CFs improve depression & anxiety and some evidence that improve self esteem, mood, self efficacy. |

| Fitzgerald et al. (2021) | Prisoners at Joyceville and Collins Bay federal prisons in Ontario | Prison farms due to re-open—450 workable acres for farming | Review and analyze Correctional Service of Canada’s (CSC) plan to reinstate two prison farms in 2021 | N/A2 part report | Part 1—Highlighted problems with proposed farm program in terms of impact on prisoners (failure to reduce recidivism and impact on human rights), the two institutions (risk of virus spread and diminished air quality) and the nearby communities (risk to air and water quality). Part 2—Outline of alternative models for CSC’s prison farms (1) organic fruit and vegetable production for prisons and community organizations (2) horticulture therapy (3) agrifood education and training |

| Hill (2008) | Prisoners in Rajasthan (n = 285 prisoners) & Kerala pisons (n = NK) | Open prisons which encompass farms/farm work | Highlight the strengths and limitations of open prisons in India | N/A | Emphasis on financial advantages of open prisons in India. Presented as more humane and conducive to the maintenance of family relationships. Open prisons are considered to be less successful with female offenders and require support from the community in which they are based. |

| Hill (2020) | 176 Male Prisoners across 2 × medium security prisons (Allendale & Wateree) and 1 maximum security (Perry) | Prisons with animal programs (Allendale—dogs, cats and bees; Perry—dogs) including farm animal program (horses and cows) at Wateree | Compare the perception of prison “pains and strains” between three groups: those in a PAP (treatment), those who have indirect contact with animals and those who have no animal contact. | Quasi-experimental using 39 item survey. Seven survey questions addressed the pains/strains of imprisonment specifically. Treatment n = 117 of which eight had farm animal (cows & calves) interaction Indirect n = 20 Control n = 39 (of which six were on the farm but without animal interaction). T Tests on nine demographic questions which were control variables. Multivariate analyses to account for differences between animal contact and no animal contact groups. Ordered logistic regression on the effect of animal contact on pains/strains of prison. |

Both direct and indirect contact with animals (dogs, cats, horses, cows, and bees) reduced perceptions of prison stressors when compared to the group who had no animal contact. In the direct and indirect animal contact groups, improvements were noted in perceptions of prisoner relationship with prison officers, self evaluation of stress and perception of threat from other prisoners. Limitations noted as self selection bias and uneven group sizes across prisons. No specific analysis in relation to dairy party. Large number of participants were from Allendale prison which was a “character based” prison. |

| Langat (2016) | Prisoners on a short term (ST) sentence (<5 months) & prison officers | Shikusa Farm Prison—100 hectares of land for crop production, cattle rearing and dairy production. | Explore effects of farming rehabilitation programs on short term offenders at a farm prison | Descriptive Research Design—Qualitative study 50 out of 339 prisoners and 20 out of 201 prison officers (random samples). Two out of five officers in charge (purposive sample) Focus Groups, Interviews and Demographic Questionnaire with prisoners, Interviews with Prison officers. Descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics. Themes and subthemes from qualitative data. |

Author concluded that ST offenders do not find farming activities appealing and view them as punitive not rehabilitative. There was considered to be a high rate of recidivism among the ST offenders. |

| Marshall and Wakeham (2015) | Ten Probation Service Users attending the SHIFT (Social Healing Through Integrated Farming Therapy) Pathways program. | Coppice Farm—a Care Farm in the Midlands with 400 sheep, 100 beef cattle and 50 acres for wheat and barley production | Evaluation of SHIFT for its effectiveness with probation service users and to add to the evidence base for Care Farming with offenders. | Mixed methods—qualitative interviews with care farmer, offender managers and offenders, case studies. Quantitative data on offending 12 months before first attendance at SHIFT and thereafter, drug and alcohol use. No details about how data was analyzed. | 10 offenders started the program, four were removed. 5 men attended at least half of the available 18 days. A case study for one man was presented which described the farm program as “life changing.” Five men all gained NOCN Level 3 award in Skills toward Enabling Progression and certification from the care farm about competency in agricultural skills which included animal care. All 10 men reported enjoying the care farm and offender managers perceived “positive change” in four of them. Authors report a reduction in offending of 65% but highlight some issues with comparability and meaningfulness of data and flaws in evaluation. |

| Miller (2019) | 1,500 Prisoners | 125 acre Prison farm | Description of the Marion County Sheriff’s office Inmate Work Farm program. | N/A | This article summarized a Master’s Student thesis (Jenkins, 2016) which focused on the work done at three different jail programs. Two of which were horticultural programs in Philadelphia and New York, and the third one was the Inmate Work Farm Program at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office in Florida. It summarized the Moore et al (2015) study and concluded that the farm work had been a “transformative learning process” which developed skills that could be used when released. |

| Moeller et al. (2018) | Adult Service users in the community and in prison. | A range of institutions including hospital/psychiatric setting (n = 34), rehabilitation (n = 11), nursing/retirement (n = 15), care farms (n = 9), prison (n = 7), womens’ shelters (n = 2), other institutions (n = 4), closed laboratory setting (n = 3) | Scoping review on nature-based interventions in institutional settings. | Scoping Review based on Arksey and O’Malley (2005) five stage process and using data from quantitative and qualitative studies. Inclusion criteria: peer reviewed journal articles in English. Approx. 3,208 adult participants based in institution where nature-based interventions for care/rehabilitation were available. Included Care Farms and PAPs. Excluded outdoor based exercise and sport based interventions, those primarily targeting physical wellbeing and natural environment therapies, adventure and wilderness programs. |

85 studies were included. Four intervention types were identified: gardening/horticulture, animal assisted therapies; care farming and virtual reality based simulations of natural environments. 8 studies were conducted at care farms (Five qualitative, two quantitative, one mixed method). Across the five qualitative studies, participants were positive about different farming activities, time spent with the animals and the farmers and the benefits of the daily work routine in a nature based environment. The two quantitative studies found that taking part in challenging and complex work tasks at the dairy farm resulted in a decline in depression and state anxiety symptoms. The mixed methods study found that spending time on a care farm increased participants’ self esteem and improved mood. Different intervention types were more popular in different institutional setting—for example, animal assisted therapy was popular in prison settings and care farms were typically used for those with employment needs and drug and alcohol addiction. Recommendations were made for classifying care farms into three types—arable farming, livestock farming and mixed farming. Future reviews were recommended to increase knowledge of the different interventions used for different groups. |

| Montford (2019) | 716 Prisoners in federal institutions with prison farms | Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) prison farms × 6 | Review and contextualize debate about re-opening of prison farms | N/A | Article provided an overview of the history of the CSC prison agriculture business and justification for prison farm closure in 2010. Perceived rehabilitative and vocational benefits of prison farming is questioned and prison agribusiness is conceptualized as an “expression of colonial, agricultural and carceral powers.” |

| Moore et al. (2015) | Low risk male prisoners | 125 acre farm open to the public and which feeds 2000 inmates per day. | Understand the experiences of participants in the Work Farm Program (WFP) | Generic Qualitative design Convenience sample of 16 male inmates. 2 person research team conducted semi structured interviews, themes identified by Straussian Grounded Theory Analysis |

Two broad categories were identified (1) Experiences in the program. The majority of the participants viewed the WFP as a positive experience although one respondent felt it was bad and hated his experience. Perceived positives grouped into four thematic categories. (1) Greater autonomy/freedom (2) Time off sentence for doing the WFP (3) Time passed more quickly (4) treatment by commanding officers. (2) Learning and Development in the program. WFP seen as a positive learning environment. Three thematic categories—(1) agricultural skills (2) job skills (3) life skills. Recommended that follow up studies track recidivism, reintegration and LT benefits of similar interventions as well as obtain staff perspectives. |

| Murray et al. (2019) | Service users in the community including offenders | Care Farms | Examine impact of care farming on quality of life, depression and anxiety among a range of service user groups. | Four Stage Systematic review. Twenty-two electronic databases were searched in 2015 and repeated in 2017. Using the PRISMA protocol, Studies included RCT’s, quasi RCT’s, interrupted time series and non randomized controlled observational studies, uncontrolled before and after studies and qualitative studies. Exclusion criteria were single subject designs, reviews surveys, commentaries, and editorials. Participants were those who receive support at a Care Farm. Eligible comparators were no intervention, waiting list control or alternative interventions. Farming interventions carried out in a hospital or prison setting were excluded. Quality of qualitative studies were evaluated by COREQ tool and EPOC and EPHPP tools used to assess risk of bias in quantitative studies. |

Eighteen qualitative and fourteen quantitative studies (one of which was mixed methods) were included. Four logical models were devised to try and explain how care farming might work for different populations—all service user groups, those with mental health/substance misuse problems, disaffected youth and people with learning disabilities. Models consisted of five main theoretical concepts—restorative effects of nature, being socially connected, personal growth, physical well being and mental wellbeing. Five categories of intervention components within the logic models were being in a group, the farmer, the work, the animals and the setting. The qualitative studies suggested 15 categories of mechanisms for change—achievement and satisfaction, belonging and non-judgment, creating a new identity, distraction, feeling valued and respected, feeling safe, learning skills, meaningfulness, nurturing, physical well-being, reflection, social relationships, stimulation, structure and understanding the self. The types of mechanisms differed according to different service user groups, implying that care farming may work in different ways according to different needs. Only the logic model for MH and substance misuse was tested because other service user groups did not have sufficient quantitative data. There was a lack of evidence to confidently assert that CF’s improve quality of life and limited evidence that they might improve depression and anxiety but some evidence to suggest they might improve self efficacy, self esteem and mood. A more robust evidence base about the impact of CF’s was hampered by design and evaluation issues in the included studies but the set of theory based logic models offers a framework for future research evaluations. |

| Steube (2016) | Low risk prisoners N = 1000 |

Vocational training center attached to Manatee county central jail | Description of LIFE program activities | N/A | Overview of the LIFE (Leading Inmates to Future Employment) program, attended by 60 males inmates a day in return for 30 days off sentence. LIFE Programs include: Animal Husbandry (5000 chickens and 100 pigs raised for eggs and pork respectively); Auto Paint and Body Repair shop; Carpentry; Custom Garment and Sewing; Diesel Engine Repair; Horticulture and Meat Processing, Welding, Aquaculture, Grist Mill, Hydraponics and Mattress Plant. For inmates who don’t qualify for the LIFE program, farming is mentioned as another work area but no further detail is provided. |

| Uddin et al. (2019) | Male Prisoners and prison officers | Two prison farms in Edo (Ozalla Farm) and Enugu states (Ibite Olo Farm) | Farm management activities and prisoner motivation to participate | Quantitative-Descriptive statistics. Questionnaires with 19 male prison officers (12 from Ozalla and 7 from Ibite Olo) Qualitative survey design for 54 prisoners (13 from Ibite Olo) and 41 from Ozalla) Data collected between July and November 2016) Explored type of agricultural activities available to prisoners, ranked preference of activities, factors motivating prisoners to participate and staff views on implementation of agricultural activities. |

Eleven agricultural activities (across both crop production and animal husbandry) were available to prisoners. Rice farming ranked as most preferred agricultural activity. Pig farming was ranked the third most popular activity and livestock seen as a valuable financial asset. In terms of factors that motivated prisoners to participate in agricultural activities, two out of 16 factors were statistically significant—increasing their chances of gainful employment post release and channeling energy toward “positive things.” Prison staff reported that the most commonly implemented programs in the prison farms were crop production but further efforts were needed to fully implement animal husbandry initiatives. |

| Welch & Elridge (2020) | Prisoners in England and Wales, UK | HMP Bristol and Prisons in England and Wales, UK | Presentation of recommendations for “greener” prisons | N/A | Overview of decline in prison farms in HMPPS between 2002 and 2005. Recommendations are made for policies that create “greener” UK prisons 1) Interior design including color of walls, optimization of natural light, indoor and in cell plants, livestreaming from animal areas to in-cell TV 2) Exterior design including pollinator friendly plants across the prison, “ time to talk” and meditation outdoor space and prison produce used in staff café 3) Education including the introduction of programs in animal husbandry, beekeeping, horticultural education, cookery. |

Evidence of the Impact of Farm Animal Work on the Rehabilitation of Adults With Criminal Convictions

The history of prison farms and their contribution toward rehabilitation from offending (reducing risk of recidivism) through increased employability skills and the positive impact of working outdoors was mentioned in several of the articles (Welch & Eldridge, 2020; Moore et al. 2015; Langat, 2016). However, the evidence about farm animal work specifically (as opposed to broader areas of agriculture not dependent on interactions with farm animals) was limited.

Four of the included records made no or very limited specific reference to the rehabilitative potential of farm animals (Hill, 2008; Steube, 2016; Miller, 2019; Uddin et al., 2019). Within the Moeller et al. (2018) review, studies based on a care farm involved participants who sought rehabilitation from mental health challenges, as opposed to reoffending, and there was little emphasis on the farm animal side of the work. This was a common theme throughout the review. Where rehabilitation from offending was considered, most studies did not explore the contribution of working with farm animals distinctly. Moore et al.’s (2015) qualitative study on the Inmate Work Farm Program at the Marion County Sheriff’s Office (MCSO) in Florida did not provide any detailed insights that were unique to those working with cows, pigs and chickens for meat and eggs. Nevertheless, the authors concluded that alongside the crop production and ornamental horticulture aspects of the program, a transformative learning experience was enabled for participants, alongside the opportunity to develop technical knowledge and interpersonal skills which “should reduce recidivism” (p. 25). Langat’s (2016) study with short term offenders on a Kenyan prison farm, considered the impact of the farming program on recidivism but the farm animal work (which included dairy production, cattle, poultry, and rabbit rearing) was not explored separately to other activities such as crop production and recidivism data was not available. Hill’s (2020) quasi-experimental study indicated that both direct and indirect contact with animals reduced the negative aspects of imprisonment by improving the relationship between correctional staff and prisoners, reducing the perception of stress and reducing institutional violence. While not evidenced within this study, the author highlighted the links between improved custodial environments, of which animal contact can be a conduit, and decreased recidivism post release. Although there was a small cohort of prisoners working with cows and calves at one of the participating prisons, this sub-group was not analyzed separately. Elsey et al.’s (2018) study of care farms in the UK, including a family run cattle farm, for those on a community probation order showed no significant difference in recidivism risk between those on a care farm and those in other programs, such as anger management or working in a second-hand clothes shop. Specific recidivism data on participants from the cattle farm was not delineated from the other care farm participants. Marshall and Wakeham (2015) reported a 65% reduction in offending as a result of participation on a care farm where probation service users had direct contact with sheep and cattle, alongside participation in a range of general farm activities such as tractor driving, hedge cutting, and wall building. This data was derived from the Police National Computer database about recorded convictions 12 months before their first attendance at the farm and recorded offenses 12 months after their first attendance at the care farm. The extent of participants’ contact with farm animals is unclear and the authors’ do not say how they handled their data on recidivism.

Fitzgerald et al.’s (2021) commentary directly challenged the rationale for the re-opening of prison farms within Ontario, Canada, one of which was that there would be a rehabilitative and therapeutic impact on prison participants working with farm animals. The authors stated that “claims of the rehabilitative impacts of working in intensive livestock operations need to be supported with empirical research” (p. 11). The lack of empirical evidence about this issue is also mentioned in Montford’s (2019) commentary, where the rehabilitative potential of penal animal agricultural programs is again questioned. Montford (2019) interpreted the distinction made by Furst (2006) between PAPs and prison based animal agriculture programs as a refutation of the rehabilitative potential of prison farm animal programs.

In summary, the review process has revealed scant evidence regarding the rehabilitative potential of farm animal work with adults who have offended, compounded by a lack of focus on the interactions with the farm animals themselves.

Farm animal Work and Rehabilitation From Offending: Mechanisms for Change Requiring Further Exploration

Only five articles addressed the mechanisms for change in farm animal work done by people with offending histories. One of the sources discussed mechanisms for change with animals in rehabilitation programs generally but without a specific focus on farm animal work. With reference to General Strain Theory, Hill (2020) discussed animals as the conduit to strain reduction in prison and as a “social lubricant” (p. 448) between prison staff and prisoners which can ultimately improve their relationship and assist in decreasing recidivism. Moore et al.’s (2015) research included quotations from prisoner participants where self-identity and labeling issues appeared important (e.g., “I don’t feel so much of an inmate”). Montford’s (2019) article indicated that the farm animal—empathy connection had been considered important by participants in the consultation events held about the re-opening of Canada’s prison farms. A former prisoner is quoted as saying “the cows taught me so many skills and they taught me patience, compassion.” Finally, Murray et al.’s (2019) paper addressed the concept of potential mechanisms for change in four groups of participants (those with mental health problems, those with substance misuse problems, disaffected youth and people with learning disabilities). Adults with criminal convictions were not represented sufficiently across the qualitative studies to constitute their own client group and to develop a distinct logic model. Nevertheless, 15 categories of mechanism for change explained how care farming might work across all the client groups and the three most common mechanisms for change were understanding the self, social relationships and belonging, and non-judgment. Murray et al. (2019) concluded that care farming may work in different ways according to different needs but that further evaluations are needed. Marshall and Wakeham’s (2015) study about probation service users’ attendance at a care farm was not designed to explore mechanisms for change specifically. Nevertheless, the evaluation mentioned the relationship and trust between the offenders and the care farmer and the connection with a rural environment as key success factors.

In summary, and not surprisingly, given the limited evidence more generally about farm animal work with an offending population, this review found that evidence regarding the potential mechanisms for change linked to farm animal work was very limited. Whilst some studies had alluded to broad mechanisms for change from farm work done by forensic service users, this was not the primary focus of the research.

The Development of a Human—Animal Bond With Food or Production Animals

Only three studies addressed the bond with food or production animals. In Uddin et al.’s (2019) Nigerian study, the food or production animals at the two participating prison farms were pigs, goats and sheep. There was no mention of prisoners preferring activities involving these animals because of a developing bond. Any preferences appeared connected to other reasons, for example, pig farming was described as being very lucrative and goat rearing was less stressful than other available activities. Two articles written in response to the Correctional Service of Canada’s (CSC) decision to re-open two of its prison farms in Ontario addressed the issue of the development of a human—food or production farm animal bond. Montford (2019) presented the position that farm animals are not considered relational, sentient beings but rather input/output machines that convert animal feed into food products such as milk, eggs, or meat. It was acknowledged that some participants at CSC’s prison farm re-opening consultation events believed that interacting with farm animals could develop empathy, patience and compassion. However, Montford (2019) presented an alternative view that focused on the potential for traumatic stress if farm animal work involved slaughtering and butchering. Fitzgerald et al. (2021) argued that industrialized animal agriculture required the animals to be objectified and an emotional distance maintained. In rejecting the notion that there are any rehabilitative or therapeutic benefits for prisoners interacting with livestock, Fitzgerald et al. asserted that “meaningful engagement with individual animals is impractical, and indeed, not encouraged” (p. 14). The authors point out that in contrast to animals used in therapeutic interventions, farm animals are numbered instead of named. It is theorized that “interactions with animals that are commodified and objectified are likely not conducive to facilitating empathy and rehabilitation” (p. 15). Fitzgerald et al. (2021) recognized that some prisoners might speak positively of their work with livestock animals in prisons but urged a balanced evaluation which also included evidence of serious emotional and physical challenges for prisoners working within intensive livestock operations.

In summary, the evidence focusing specifically on the development of a bond between forensic service users and farm animals is not only scant but requires further evaluation in terms of both positive and potential negative effects.

The Experiences of Forensic Service Users and Dairy Cattle Work

This review sought to explore the evidence about the experiences of forensic service users with dairy cattle in particular. The distinction between dairy cattle and beef cattle is important because of the higher level of daily physical contact that farm workers have with dairy cattle compared to beef cattle. Within articles in this review, the distinction was not always clear (e.g., Elsey et al., 2018; Steube, 2018). Limited research on people with offending histories who work with dairy cattle was identified. In Hill’s (2020) study, only one of the three participating prison farms (Wateree Correctional Institution) had a dairy farm where eight prisoners took care of the cows and their calves. While they were included as part of the animal work treatment group which was compared with indirect animal contact and no animal contact farm work, Hill (2020) did not investigate their experiences as a standalone group. Fitzgerald et al. (2021) noted that the re-opening of the two CSC prison farms included plans for a herd of 90 dairy cows on site by August 2023. Whilst no specific evaluations of previous prison dairy farm work were referenced, the authors included quotations from former dairy party prisoners to challenge the wisdom of the re-opening plans. The fear factor of working with cows (linked to their size and nature) was emphasized as well as the specific risks posed to prisoners and the deleterious impact on them when they were required to take calves from their mothers. Montford’s (2019) paper included references to some benefits (increased skills, patience and compassion) reported by former prison dairy farm workers as a result of working directly with the dairy cattle.

Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review followed a structured and transparent search process, which included a broad range of studies from a number of different databases and search engines. This facilitated a thorough understanding of the current international evidence base. Nevertheless, it is possible that some studies may have been missed from databases that were not searched, for example those specific to farming and agricultural literature. It is also possible that the focus on adults with offending histories has resulted in the omission of some relevant research in the area of farm animal work conducted with young people who have offended and either been incarcerated or subject to youth justice community sanctions. Whilst the scoping review methodology excludes an assessment of the quality of the included records, there were some clear methodological shortcomings with many of the studies included in this review and so comment on implications for policy or practice is not appropriate.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In summary, this review of the evidence from the last 15 years suggests that farm animal work and dairy cattle work specifically and its potential impact on rehabilitation from offending is considerably under-researched. This is perhaps unsurprising given that this area of criminal justice practice is one which has historically been positioned primarily within the employment and labor spheres. Despite recognizing the controversy surrounding livestock and their contribution toward climate change, farm food and production animal work is likely to continue to feature in the rehabilitative or vocational pathways of people who have offended. Good quality research is needed to expand the knowledge base in this area to establish rehabilitative and recidivism outcomes. Positive outcomes are suggested in the literature but more rigorous research is needed to clarify this. Careful attention needs to be paid also to negative outcomes from working with animals who may have to be slaughtered or who may be seen to be distressed by farming processes. It is important to identify mechanisms for change to begin to develop a theoretical perspective to inform the effective use of this type of work in rehabilitation efforts. The broad question to be addressed is, what type of animal-based farm work rehabilitates which types of offenders and how does it have this effect? Given the heterogeneity of farm animals, this research should delineate between different types of farm animals (e.g., goats, sheep, cattle) and their impact on rehabilitation from offending. This review has also illustrated that the concept of a human—food or production animal bond should not be summarily dismissed but instead researched further to understand under what conditions and with which farm animals, a bond might develop, alongside any benefits and challenges this might bring. Despite the advent of modern machinery, there remains a need for a high level of physical contact with humans when moving dairy cattle into milking parlors and within general care for them and their offspring. These intimate and nurturing activities should specifically be investigated further and negative as well as positive outcomes should be studied.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Libby Payne  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5096-4703

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5096-4703

References

- Artz B., Davis B. D. (2017). Green Care: A review of the benefits and potential of animal-assisted care farming globally and in rural America. Animals (Basel), 7(4), 31. 10.3390/ani7040031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aromataris E., Munn Z. (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. 10.46658/JBIMES-20-01 [DOI]

- Bachi K. (2013) Equine-facilitated prison-based programs within the context of prison-based animal programs: State of the science review. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 52(1), 46–74. 10.1080/10509674.2012.734371 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke B. J., Hill L. B., Farrington D. P., Bales W. D. (2021). A beastly bargain: A cost-benefit analysis of prison-based dog-training programs in Florida. The Prison Journal (Philadelphia, PA.), 101(3), 239–261. 10.1177/00328855211010403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke B. J., Farrington D. P. (2015). The effects of dog-training programs: Experiences of Incarcerated Females. Women & Criminal Justice, 25(3), 201–214. 10.1080/08974454.2014.909763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke B. J., Farrington D. P. (2016). The effectiveness of dog-training programs in prison: A systematic review and metaanalysis of the literature. Prison Journal, 96, 854–876. [Google Scholar]

- Elsey H., Farragher T., Tubeuf S., Bragg R., Elings M., Brennan C., Gold R., Shickle D., Wickramasekera N., Richardson Z., Cade J., Murray J. (2018). Assessing the impact of care farms on quality of life and offending: A pilot study among probation service users in England. BMJ Open, 8(3), 1–11. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald A. J., Wilson A., Bruce J., Wurdemann-Stam A., Neufeld C. (2021, January 31). Canada’s proposed prison farm program: Why it won’t work and what would work better. Evolve Our Prison Farms. https://www.evolveourprisonfarms.ca

- Furst G. (2006). Prison-based animal programs: A national survey. The Prison Journal (Philadelphia, PA.), 86(4), 407–430. 10.1177/0032885506293242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn E., Combs K. M., Gandenberger J., Tedeschi P., Morris K. N. (2020). Measuring the psychological impacts of prison-based dog training programs and in-prison outcomes for inmates. The Prison Journal (Philadelphia, PA.), 100(2), 224–239. 10.1177/0032885519894657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill G. (2008). The value of open prisons in India. Corrections Compendium, 33(3), 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hill L. (2020). A touch of the outside on the inside: The effect of animal contact on the pains/strains of imprisonment. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 59(8), 433–455. 10.1080/10509674.2020.1808558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins R. (2016). Landscaping in lockup: The effects of gardening programs on prison inmates [Master’s thesis, Arcadia University]. https://scholarworks.arcadia.edu/grad_etd/6/

- Kaplan S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature—Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182. 10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz-Lomelin A., Nordberg A. (2020). Assessing the impact of an animal-assisted intervention for jail inmates. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 59(2), 65–80. 10.1080/10509674.2019.1697786 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. Y., Kim S. Y., Kwon H. J., Park S. A. (2021). Horticultural therapy program for mental health of prisoners: Case report. Integrative Medicine Research 10(2), 100495. 10.1016/j.imr.2020.100495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langat K. (2016). Effects of farming rehabilitation programmes on short term offenders serving in Shikusa farm prison in Kakamega County, Kenya. International Journal of Novel Research in Humanity and Social Sciences, 3(3), 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall D., Wakeham C. (2015). SHIFT care farm: Evaluation report for one cohort of offenders under the SHIFT Pathways approach for the use of a care farm for the management of offenders. The Bulmer Foundation. https://www.brightspacefoundation.org.uk/sites/default/files/imce/2015-01%20SHIFT%20Care%20Farm%20evaluation%20report%20final.pdf

- Miller R. (2019). Jail garden and farm programs yield benefits for inmates. American Jails, 33(4), 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Mims D., Waddell R., Holton J. (2017). Inmate perceptions: The impact of a prison animal training program. Social Criminology, 5(2), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller C., King N., Burr V., Gibbs G. R., Gomersall T. (2018). Nature-based interventions in institutional and organisational settings: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 28(3), 293–305 10.1080/09603123.2018.1468425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), 1006–1012. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A. A. (2020). “Came for the horses, stayed for the men”: A mixed methods analysis of staff, community, and re-entrant perceptions of a prison-equine program (PEP). Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 59(3), 156–176. 10.1080/10509674.2019.1706688 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moriggi A., Soini K., Bock B. B., Roep D. (2020). Caring in, for, and with nature: An integrative framework to understand green care practices. Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), 12(8), 3361. 10.3390/SU12083361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray J., Wickramasekera N., Elings M., Bragg R., Brennan C., Richardson Z., Wright J., Llorente M. G., Cade J., Shickle D., Tubeuf S., Elsey H. (2019). The impact of care farms on quality of life, depression and anxiety among different population groups: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Review, 15(4), e1061. 10.1002/cl2.1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A., Freer T., Samuel N. (2015). Correctional agriculture as a transformative learning experience: Inmate perspectives from the Marion County Sheriffs Office inmate work farm program. Journal of Correctional Education, 66(3), 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Montford K. (2019). Land, agriculture and the carceral: The territorializing function of penitentiary farms. Radical Philosophy Review, 22(1): 113–141. 10.5840/radphilrev20192494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters M. D. J., Godfrey C., McInerney P., Munn Z., Tricco A. C., Khalil H. (2020). Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In Aromataris E., Munn Z. (Eds.). Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual, JBI. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/

- Steube B. (2016). Everyone benefits when inmates work in Manatee County. American Jails, 30(5), 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A. C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K. K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M. D. J., Horsley T., Weeks L., Hempel S., Akl E. A., Chang C., McGowan J., Stewart L., Hartling L., Aldcroft A., Wilson M. G., Garritty C., . . . Straus S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin I. O., Igbokwe E. M., Olaolu M. O. (2019). Prison farm inmates’ reformation and rehabilitation: The Nigerian experience. Kriminologija I Socijalna Integracija, 27(2), 204–220. 10.31299/ksi.27.2.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Wormer J., Kigerl A., Hamilton Z. (2017). Digging deeper: Exploring the value of prison-based dog handler programs. The Prison Journal, 97(4), 520–538. 10.1177/0032885517712481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villafaina-Dominguez B., Collado-Mateo D., Merellano-Navarro E., Villafaina S. (2020). Effects of dog-based animal-assisted interventions in prison population: A systematic review. Animals (Basel), 10(11), 1–19. https://doi:10.3390/ani10112129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch B., Eldridge H. (2020). An action plan for greener prisons. http://sustainablefoodtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/An-Action-Plan-for-Greener-Prisons.-SFT-Report-2020-1.pdf

- Wilson E. O. (1984). Biophilia. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]