Abstract

Background:

Obstructive airway complications (OACs) represent a significant problem after lung transplantation (LTx). Bilateral OACs after double lung transplantation are infrequently reported.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to investigate management and outcome of OAC.

Design:

Retrospective single-center cohort study

Methods:

Adult patients with bilateral LTx performed between 2010 and 2021 were included. Patients with follow-ups of less than 3 months and after heart–lung transplantation were excluded. OAC was defined either as the need for stenting, surgical revision, or balloon dilatation. Outcome parameters included graft survival, graft function, quality of life, and management.

Results:

During the study period, 1,170 patients were included. Hundred thirty-five (11.5%) patients developed OAC. Forty-six (4.4%) patients had significant bilateral OAC. Thirty-seven (80%) bilateral OAC patients were treated by stent insertion; in 34 patients, biodegradable stents were used. The median number of bronchoscopies in bilateral OAC was 26 during the first postoperative year compared with nine in controls (p < 0.001). Fourteen OAC patients (n = 10 bilateral) underwent surgical revision including six re-do transplantations. Graft loss occurred significantly more frequently in patients with bilateral OAC with a graft survival of 63% and 50% in these after 3 and 5 years compared with 83% and 73% in controls without OAC (p < 0.001). Baseline forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) in patients with bilateral OAC was median 58% predicted in comparison with 90% in controls (p < 0.001). Quality of life was significantly reduced.

Conclusion:

Bilateral OACs impose a high burden of disease on patients after lung transplantation and were associated with early and late graft loss. Affected patients’ OAC demonstrated reduced graft function and impaired quality of life. Most OACs were managed by bronchoscopy preferably by non-permanent stenting. Surgery including re-do transplantation was used in selected cases.

Keywords: biodegradable implants, bronchoscopy, graft survival, lung transplantation, stents

Introduction

Airway complications represent a significant problem after lung transplantation (LTx). Airway complications can be divided into obstructive and necrotic complications. The latter occur within weeks after LTx and are nowadays usually managed by observation only, but frequently result in later obstructive complications by aberrant wound healing. Obstructive airway complications (OACs) are more frequent and occur later than necrotic complications, usually within months after transplant. The onset of virtually all OAC is within the first postoperative year, and its reported incidence ranges from 2.6% to 24.6%.1–10 The proportion of bilateral OAC in patients after sequential bilateral LTx is seldom reported.

Pathogenesis and risk factors of airway complications after LTx have been studied in various publications.5,11–13 Extensive necrosis as a consequence of airway ischemia is the most important risk factor of later OAC. Fungal infections and surgical techniques are also associated with the development of airway complications but may be related to airway ischemia themselves. Airway ischemia in the post-anastomotic region is caused by several factors. During transplantation, the arterial systemic blood supply is not restored routinely. Spontaneous reestablishment of bronchial arterial circulation can take several weeks. The viability of the donor bronchus during this interval depends on the retrograde blood flow from the pulmonary circulation through collaterals. The surgical technique seems to play a role 14 as well as postoperative management. Postoperative hypotension and volume depletion should be avoided. 12 OAC may manifest clinically as malacia, strictures, or excessive granulation tissue, and management is usually done by bronchoscopy. Various endoscopic techniques are reported, including mechanical 15 and thermal debulking (cryotherapy, 16 laser, 17 electrocautery, 18 and argon therapy), 19 balloon bronchoplasty, 20 insertion of various types of stents,3,21,22 topical administration of drugs, 23 and brachytherapy. 24 Occasionally, surgery is performed in selected cases and OAC may be an indication for re-do transplantation.

OACs demonstrate a high rate of recurrence and may impair quality of life (QoL) due to frequent bronchoscopies, reduced graft function, and infectious complications, but the exact extent is unknown.

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact, management, and outcome of bilateral OACs in a large LTx cohort with a hypothesis of impaired graft survival and increased morbidity.

Methods

A retrospective case–cohort study was performed in a large lung transplant program. The study was conducted following the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. Patients signed informed consent for anonymized data analysis in retrospective studies within the German Center of lung research. The use of data to conduct retrospective analysis was covered by the ethics committee’s vote (No 2923-2015, update September 24, 2021).

All adult patients with bilateral LTx (including combined non-thoracic and bilateral lung) performed between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2021 were included. Patients with follow-up of less than 3 months were excluded as well as heart–lung transplant recipients because of a single tracheal anastomosis. For all patients, the first transplantation during the study period was included. Graft loss was defined as death or re-do transplantation.

Antifungal prophylaxis was applied to all patients for at least 6 months with azoles and additional inhaled liposomal amphotericin B for 3 weeks. Routinely, patients received a 1- to 2-week course of broad-spectrum antibiotics tailored to results of intraoperative cultures after surgery. In cases of suspected mucosal infection of the anastomotic and post-anastomotic regions, multiple biopsies were taken from these regions for cultures and histopathology. Fungal infection of the anastomotic and post-anastomotic regions was defined by macroscopic appearance plus positive cultures and/or the presence of fungal infection on histopathology.

Data were extracted from a database containing all transplant bronchoscopies (n = 32,920) performed by the Department of Respiratory Medicine since 2008. Additional clinical data were extracted from medical records. Follow-up ended on July 31, 2022 or at graft loss, whichever occurred first. Relevant OACs were defined as the need for stenting, surgical revision, or balloon dilatation (or mechanical dilatation by endoscopes larger than 6 mm outer diameter) as suggested in the literature. 7 Airway complications were graded according to the S (stenosis) subdomain of the 2019 International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) consensus document, 25 whenever photographs or videos of the anastomosis were available. Strategies to control observation were addressed by crosschecking selection by two investigators independently, and corroboration of multiple information sources (databases for bronchoscopy and transplantation plus medical records).

Lung-transplanted patients were followed in a specialized outpatient clinic in intervals depending on the time after transplantation and clinical stability. Loss of follow-up in our program is less than 5%. Bronchoscopy with broncho-alveolar lavage and transbronchial biopsy was performed routinely during the first year weekly until week 3 and the months 1, 3, 6, and 12 and whenever clinically indicated thereafter. Acute rejection was graded by histopathology according to current standards. 26 In patients with an intervention for OAC, intervals between 1 and 4 weeks were used until clinical stability was reached. Case management by telephone or video consultations was offered to all patients between visits. At each appointment in the outpatient clinic history, physical exam, spirometry, and laboratory tests including immunosuppressant levels were obtained. Self-rated levels of health perception and QoL were assessed routinely on each visit using a visual analog scale by asking patients: ‘On a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 meaning perfectly healthy, what is you perceived health today?’. 27

All endoscopic interventions for OAC were performed by experienced pulmonologists. The majority of interventions were performed with flexible bronchoscopes (BF-1TQ180, BF1T180, BF-1TH190, BF- P190, BF 3C40, all Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Endoscopic treatment was based on underlying problems (e.g. granulation tissue, malacia, strictures) and time after transplant. In brief, early after LTx (first 3 months), mechanical debridement by forceps was undertaken and after 3 months excessive granulation tissue leading to airway obstruction was removed by thermal therapy (argon plasma, coagulation, electrocautery, or cryotherapy, Erbe, Tübingen, Germany). Strictures were treated by balloon dilatation (CRE™ graduated Pulmonary Balloon Dilatation Catheter 6–8 or 8–10 mm, Marlborough, MA, United States). Recurrent strictures after more than two dilatation procedures or significant malacia were treated with biodegradable (DV stent, ELLA_CS, Hradec Králové Czech Republic) or self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) (Bronchus Stent TTS, Alveonova, Aachen, Germany) at least 6 months after surgery. Stents were inserted in general anesthesia and stents were deployed via direct vision as previously described. 22 Routine endoscopic follow-up after stent insertion was performed after 3 days, and then in 2- to 4-week intervals until 4 months. Topical mitomycin or paclitaxel drug-coated balloons were used in recurrent strictures occasionally until 2015. Residual strictures were defined as freedom from any intervention for at least 3 months on the last follow-up and a reduction of more than 50% in the cross-sectional area on a lobar level on bronchoscopy.

Transplant procedures were performed by cardiac surgeons. Surgical revisions for OAC were performed by thoracic surgeons.

Spirometry was performed according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society guidelines 28 with reference values of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) based on European Community for Steel and Coal. 29 Chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) was defined as persistent FEV1 < 80% in of the baseline FEV1 according to recently established criteria. 30

Baseline allograft dysfunction was defined by FEV1 and FVC below 80% predicted as proposed by Liu et al. 31

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with metric variables expressed as medians, and 25% and 75% quartiles, and categorical variables by absolute numbers and percentage of data entries. Univariate analyses were performed using the median test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method. The last observation was the last visit of the patient. Cox regression multivariate analysis was conducted to analyze survival. The level of significance was set at ⩽ 0.10 for including variables identified by univariate analysis between groups. Two control groups for bilateral OAC were used (1) patients without OAC and (2) patients with unilateral OAC to study the effect magnitude. No imputation for missing data was performed but variables with a proportion of > 30% missing were excluded.

Results

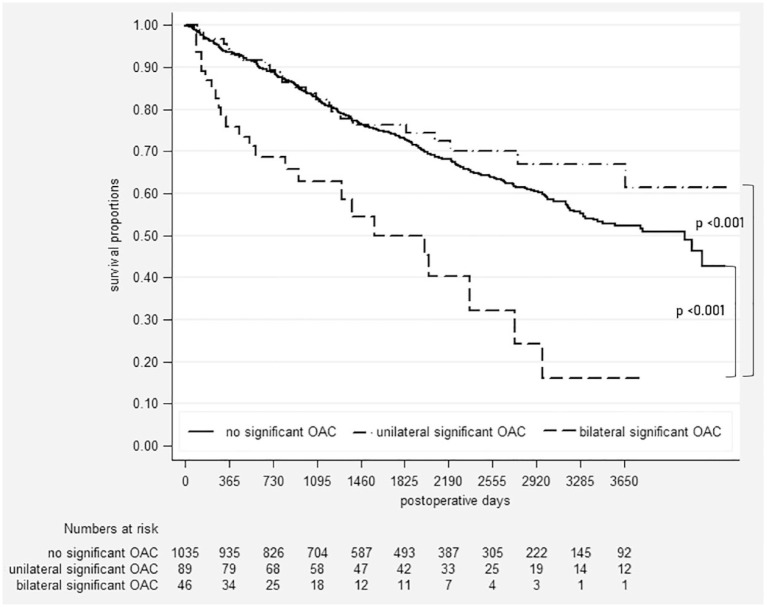

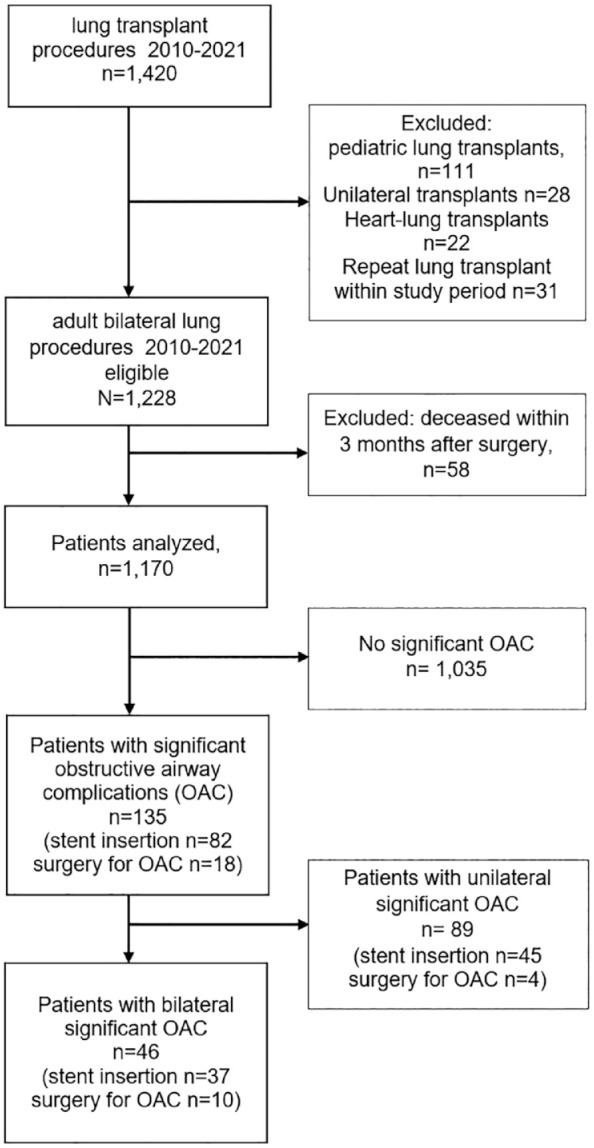

Among 1,420 patients transplanted during the study period, 1,170 were included in our analysis (Figure 1). Hundred thirty-five (11.5%) patients developed a relevant OAC with a median onset of 84 days (25 and 75 quartile; 63, 112 days) after LTx. Forty-six (4.4% of the total cohort and 34% of all OACs) patients had significant bilateral OAC. The incidence of bilateral OAC increased from 3.1% (26 cases of 835 LTx) between 2010 and 2018 to 10.0% (20 of 200) from 2019 to 2021. The proportion of bilateral OAC of all OACs reached 53% in the most recent period.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of patients.

OAC, obstructive airway complications.

Patient demographics are displayed in Table 1. Lung–liver transplantation was the underlying procedure in five patients, two of these experienced significant unilateral OAC and no lung–liver recipient developed bilateral OACs.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Variable | Patients without OAC (n = 1,035) | Patients with unilateral OAC (n = 89) | Patients with bilateral OAC (n = 46) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 499 (48) | 30 (34) | 12 (26) | < 0.001 |

| Male | 536 (52) | 59 (66) | 34 (74) | |

| Age at transplant, median years (25th, 75th percentiles) | 43 (53, 59) | 40 (51, 57) | 40 (54, 59) | 0.169 |

| Recipient smoking history, n (%) | 516 (50) | 36 (40) | 29 (64) | 0.041 |

| Steroid use pre-transplant, n (%) | 393 (37) | 30 (35) | 15 (32) | 0.650 |

| Body mass index, median kg/m2 (25th, 75th percentiles) | 21 (19, 24) | 21 (19, 23) | 22 (18, 23) | 0.311 |

| Lung allocation score a at transplant, median (25th, 75th percentiles) | 36 (33, 42) | 34 (32, 38) | 37 (32, 41) | 0.112 |

| Bridged by mechanical support, b n (%) | 74 (7) | 6 (7) | 1 (2) | 0.431 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Emphysema/alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | 324 (31) | 27 (30) | 10 (23) | 0.224 |

| Fibrosis/interstitial lung disease | 331 (32) | 28 (31) | 14 (32) | |

| Cystic fibrosis/bronchiectasis | 177 (17) | 22 (24) | 13 (30) | |

| Pulmonary hypertension/vascular diseases | 57 (6) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | |

| Other | 146 (14) | 13 (14) | 6 (14) | |

OAC, obstructive airway complication.

Available in 985, 74, and 41 patients.

Pre-transplant extracorporeal support or invasive mechanical ventilation.

In patients with available photo or video documentation (n = 122), six (5%) had isolated anastomotic lesions, 92 (75%) had anastomotic plus lobar/segmental lesions, and 24 (20%) had lobar/segmental lesions only according to the ISHLT consensus document. All OAC lesions had a more than 50% reduction in cross-sectional area (extent c and d).

Endoscopic management

In 271 (23%) patients, endoscopic recanalization for excessive granulation tissue was performed on at least one occasion early after transplantation. The first endoscopic recanalization occurred after a median of 84 days (25% and 75% quartiles, 63, 112 days). Fifty percent of patients with early endoscopic recanalization developed later significant OAC. Eighty-two (61%) patients were treated by stent insertion (Table 2) and 135 (11.5%) patients by endoscopic dilatation. First dilatation was performed median of 172 days after transplantation (25% and 75% quartiles, 111 and 215 days). Balloon dilatations were repeatedly performed in 73% of patients with a median of two sessions (25% and 75% quartiles, 1 and 4). Most patients (86%) were treated with biodegradable stents, in nine patients, both SEMS and biodegradable stents were used. Slightly more target lesions in significant OAC (n = 98, 54%) were located on the right side than on the left side (n = 83, 46%). The proportion of patients receiving stents increased from 7.1% (59 of 835) from 2010 to 2018 to 11.5% (23 of 200) between 2019 and 2021.

Table 2.

Treatment and outcomes.

| Variable | Patients without OAC (n = 1,035) | Patients with unilateral OAC (n = 89) | Patients with bilateral OAC (n = 46) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graft loss, n (%) | 340 (33) | 24 (27) | 24 (52) | 0.011 |

| Death, n (%) | 316 (31) | 20 (23) | 15 (33) | 0.261 |

| Re-do transplantation, n (%) | 24 (2) | 4 (4) | 9 (20) | 0.019 |

| Days until first outpatient visit, median days (25th, 75th percentiles) | 27 (31, 39) | 26 (31, 35) | 27 (32, 45) | 0.417 |

| Bronchoscopies during first postoperative year, median (25th, 75th percentiles) | 9 (8, 11) | 21 (17, 27) | 26 (31, 40) | < 0.001 |

| Anastomotic dehiscence, n (%) | 22 (2) | 11 (13) | 11 (24) | < 0.001 |

| Number of transbronchial biopsies within first 2 postoperative years, n | 4.495 | 907 | 94 | |

| Biopsy grade A1, n (%) | 529 (12) | 125 (14) | 12 (13) | 0.226 |

| Biopsy grade A2 and above, n (%) | 160 (3) | 29 (3) | 2 (2) | 0.701 |

| Biopsy proven bronchial fungal infection within first 6 postoperative months, n (%) | 37 (4) | 5 (6) | 3 (7) | 0.396 |

| Stents per patient, median (25th, 75th percentiles) | – | 1 (0, 1) | 1 (1, 2) | < 0.001 |

| Use of biodegradable stents, n (%) | – | 44 (48) | 34 (77) | 0.001 |

| Use of self-expandable metal stents, n (%) | – | 7 (8) | 6 (14) | 0.272 |

| Use of topical mitomycin or paclitaxel, n (%) | – | 9 (10) | 1 (2) | 0.095 |

| Airway colonization, n (%) | 120 (12) | 8 (9) | 16 (35) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic lung allograft dysfunction, n (%) | 289 (28) | 22 (24) | 6 (14) | 0.117 |

| Baseline FEV1 < 80% predicted, a n (%) | 299 (30) | 47 (57) | 33 (79) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline FVC < 80% predicted, a n (%) | 170 (18) | 18 (22) | 18 (43) | < 0.001 |

| Baseline FEV1 and FVC < 80% predicted, a n (%) | 61 (7) | 13 (17) | 8 (25) | < 0.001 |

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; OAC, obstructive airway complication.

n = 914, n = 80, and n = 30 patients evaluable.

Hundred fourteen biodegradable stents were inserted in 78 patients during the study period. Twenty-two patients received more than one biodegradable stent. Early migration leading to stent extraction occurred in two stent procedures (2%) and two patients. Copious secretions with the need for bronchoscopic intervention were observed in 10 cases (9%). Granulation tissue with stent obstruction leading to endoscopic recanalization occurred in 15 (13%) cases. Re-stenosis after stent degradation was observed in 21 cases (18%). No death related to the insertion of a biodegradable stent was noted.

First-year bronchoscopies (Table 2) were increased by 178% in patients with OAC compared with those in patients without OAC. Stents were used more frequently in bilateral OAC than in unilateral OAC. Biodegradable stents were used most frequently.

Significantly, more endoscopic interventions were performed in patients with OAC during the first postoperative year (Table 2). Freedom from any intervention was 82%, 93%, and 98% after 1, 2, and 3 years, respectively, following transplantation in patients with OAC. In 84 (62%) OAC patients, residual strictures were present during the latest follow-up bronchoscopy. In 72 (86%) of these patients, the middle lobe was involved, in 40 (48%) patients, upper lobes were affected, and in 9 (11%) patients, lower lobes could not be intubated. In 36 (43%) patients, more than one residual stricture on the lobar level was present. Residual strictures were more frequent in recipients affected by bilateral OAC (p < 0.001). Thirty-eight percent of these patients had at least one lobar bronchus occluded or severely narrowed. In 22 (48%) patients, more than one lobe was involved. In unilateral OAC patients, 53% had at least one residual stricture, and in 16%, more than one lobe was affected.

Thoracic surgery

Fourteen patients underwent thoracic surgery for OAC including six re-do transplantations with OAC (all were bilateral OAC) as the primary indication (n = 5 bilateral, n = 1 unilateral). Sleeve resection was performed in four patients (three with bilateral OAC), and two cases of lobectomy and each a single case of bi-lobectomy (all lobectomies were in unilateral OAC patients) and pneumonectomy (a patient with bilateral OAC) due to infectious post-obstructive complications. No recurrence of significant OAC was observed after thoracic surgery for OAC. Re-do transplantations were performed after a median of 217 days after primary transplantation. All patients undergoing thoracic surgery for OAC underwent prior balloon angioplasty and nine had prior stent insertion. Three patients with bilateral OAC underwent later re-do transplantation due to CLAD.

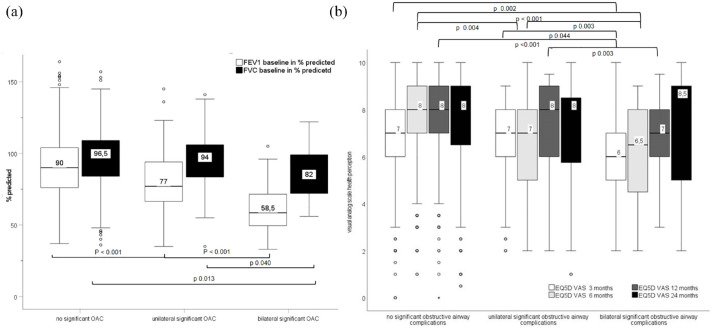

Graft survival

Three hundred fifty-one patients died during follow-up, 20 deaths occurred in patients with unilateral OAC, and 15 died in the subgroup of patients with bilateral OAC. Thirty-seven patients underwent re-do transplantation, four in the subgroup with unilateral OAC, and 15 (33%) in the subgroup with bilateral OAC. The majority of graft losses were attributed to death in all groups and the proportion of patients undergoing re-do transplantation increased from 2% in patients without OAC to 4% and 20% in patients with unilateral and bilateral OACs, respectively (Table 2). Overall graft loss occurred significantly more frequently in the subgroup of patients with bilateral OAC (Table 2 and Figure 2). Graft survival after 1, 3, and 5 years was 93/83/73%, 93/83/75%, and 76/63/50% in patients without, with unilateral, and with bilateral OACs, respectively (Figure 2). There was no difference in survival between patients with unilateral OAC and patients without OAC (log-rank p = 0.279). Development of bilateral OAC was independently associated with graft loss with an adjusted hazard ratio of 2.31 (95% confidence interval: 1.27, 4.18; see Table 3). Causes of death (n = 15) in patients with bilateral OAC were respiratory failure in seven, infection/sepsis in four, pulmonary bleeding in one, malignancy in one, and CLAD in two.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve of graft survival.

OAC, obstructive airway complications.

Table 3.

Survival analysis.

| Covariate | N | Survival (months), median (95% CI) | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p | |||

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||

| 18–46 years | 359 | 66 (58, 71) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| 47–53 years | 239 | 62 (52, 67) | 1.33 (1.00, 1.764) | 0.047 | 1.21 (0.83, 1.76) | 0.327 |

| 54–59 years | 345 | 49 (42, 58) | 1.26 (0.96, 1.65) | 0.09 | 1.26 (0.85, 1.87) | 0.253 |

| 60 years and older | 227 | 46 (40, 56) | 1.61 (1.22, 2.14 | 0.001 | 1.47 (0.98, 2.19) | 0.061 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 628 | 57 (51, 61) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | ||

| Female | 539 | 58 (50, 62) | 1.10 (0.03, 1.35) | 0.335 | ||

| Primary disease, n (%) | ||||||

| Emphysema incl. alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | 361 | 49 (44, 59) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Pulmonary vascular disease | 59 | 52 (42, 69) | 0.92 (0.57, 1.475) | 0.723 | 1.13 (0.66, 1.942) | 0.656 |

| Cystic fibrosis/bronchiectasis | 212 | 67 (62, 74) | 0.61 (0.44, 0.85) | 0.003 | 0.81 (0.51, 1.29) | 0.379 |

| Fibrosis/interstitial lung disease | 373 | 55 (47, 60) | 1.05 (0.82, 1.35) | 0.696 | 1.02 (0.77, 1.35) | 0.888 |

| Other (incl. re-do transplantation) | 165 | 55 (41, 64) | 1.33 (0.99, 1.79) | 0.06 | 1.09 (0.74, 1.59) | 0.669 |

| Chronic lung allograft dysfunction, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 828 | 62 (54, 69) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Yes | 317 | 57 (51, 60) | 2.37 (1.93, 2.91) | 0.422 | 2.62 (2.09, 3.29) | < 0.001 |

| Metastatic tumor disease after transplantation, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 1,124 | 58 (52, 61) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Yes | 46 | 41 (31, 64) | 3.87 (2.83, 5.28) | < 0.001 | 3.80 (2.69, 5.39) | < 0.001 |

| Obstructive airway complication, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 1,035 | 58 (53, 61) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Unilateral | 89 | 55 (42, 70) | 0.82 (0.55, 1.23) | 0.336 | 0.75 (0.46, 1.22) | 0.241 |

| Bilateral | 46 | 31.5 (19, 43) | 2.40 (1.57, 3.66) | < 0.001 | 2.31 (1.27, 4.18) | 0.006 |

| Baseline lung allograft dysfunction n (%) | ||||||

| No | 942 | 61 (58, 65) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) | (Ref.) |

| Yes | 82 | 55 (44, 68) | 1.43 (0.99, 2.07) | 0.055 | 1.41 (0.96, 2.08) | 0.083 |

CI, confidence interval.

Bold values were associated with mortality.

Graft function

Baseline FEV1 was significantly lower in patients with OAC in comparison with patients without OAC (Figure 3(a)) and effects were more pronounced in patients with bilateral OAC resulting in a median baseline FEV1 of 58% predicted in comparison with 90% predicted in recipients without OAC. In contrast to patients affected by unilateral OAC only, bilateral OAC patients had an additional and significant reduction of FVC to a median 82% compared with 97% in patients without OAC. Baseline allograft dysfunction was present in every fourth recipient affected by bilateral OAC and this was significantly increased in comparison with controls (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Baseline graft function (a) in percent predicted and patient reported health perception (b, visual analogue scale).

EQ5D, patient reported EuroQol health perception questionnaire; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity, OAC, obstructive airway complications; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Three hundred seventeen patients developed CLAD; 289 (28%) patients without OAC developed CLAD, 22 (25%) patients with unilateral OAC, and six CLAD patients had bilateral OAC. The median time to development of CLAD was shorter in patients with bilateral OAC (545 days) in comparison with patients with unilateral (717 days) or without OAC without reaching statistical significance (p = 0.142).

Quality of life

Patient’s health perception on a visual analog scale was significantly reduced in patients with bilateral OAC up to 1 year after LTx. Within the first 6 months, also patients with single-sided OAC reported a reduced health perception compared with controls without OAC (Figure 3(b)).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that bilateral OACs have a considerable negative impact on graft survival, graft function, long-term complications, and early QoL in LTx patients. Endoscopic management of bilateral OAC is challenging and most patients are treated by stent insertion, some will benefit from surgical revision.

Published data reporting the incidence of bilateral OAC after LTx are scarce. Bilateral OAC affected just a single LTx patient of 1,555 (0.1%) in a single-center study 7 and less than 2% of all anastomotic airway complications were bilateral in another single-center analysis of 490 patients after transplantation. 10 When applying the same definition of OAC as the Vienna group, our overall incidence was more than four times higher and the proportion of bilateral OAC was almost 40-fold increased in our program. Risk factor analysis is beyond the scope of our article, but surgical technique and early postoperative management to optimize perfusion seem to be surgical for prevention of later OAC. Airway ischemia seems to be the most important risk factor for OAC. 12 A lower incidence of OAC has been reported uniformly by centers in which only thoracic surgeons perform airway anastomosis in LTx.7,10,13,14

There are conflicting reports about the impact of OAC on survival in lung transplant recipients. Murthy et al. 5 reported an impaired 2-year survival of 60% in 67 patients affected by OAC in comparison with 75% of controls. Also, a registry analysis of 233 cases reported a 3-year survival of 39% compared with 68% in controls. 32 In 111 LTx patients treated with SEMS after LTx, 5-year survival was 60% compared with 76% in controls. 33 No difference in survival was reported by two other authors4,6 involving 50 recipients in total. In our study, a negative impact on survival was only observed in transplanted patients with significant bilateral OAC.

To our knowledge, there are few publications focusing on the effect of OAC on baseline FEV1. Mazzetta et al. 4 reported a 25% lower baseline FEV1 in 22 bilateral LTx patients affected by OAC compared with 139 controls without differentiating between unilateral or bilateral OAC. In another retrospective study, 6-month FEV1 in percent predicted was reduced from 68 to 58.5 (relative –17%) in 34 patients with OAC. 2 In our study, patients with bilateral OAC lost 35% of baseline FEV1, which confirms this observation. Lower baseline FEV1 is associated with impaired survival in various publications31,34,35 and was associated with a higher incidence of CLAD or earlier onset.34–36 Baseline allograft dysfunction may explain the earlier onset of CLAD in our cohort, although this missed statistical significance is probably explained by low patient numbers.

In multivariate analysis, bilateral OAC but not BLAD was associated with graft loss in our study. Retrospective studies from Strasbourg 4 and Temple University reported 1 increased infection rates in 35 and 22 patients affected by OACs, respectively. Our group published in 2010 a 45% rate of airway colonization in patients treated with SEMS. 3 No details were available from the two other publications about their use of stents and airway colonization. Because of the predominant use of biodegradable stents in 82 patients of our study, the use of stents alone might not explain an increased risk of colonization in OAC patients. A median time to stent degradation of 4.5 months is observed in LTx patients and significant improvement of pulmonary function after insertion.22,33 Duration of follow-up bronchoscopies decreased after stent insertion in most of our patients and the majority (app. 60%) received bronchoscopy just for airway clearance. Nevertheless, residual strictures causing impairment in lung function and increased rate of infection were frequent in our cohort even when target lesions remained patent after degradation of stents. The idea of non-permanent stenting in anastomotic complications after LTxs and in benign airway stenosis, in general, is attractive and can be achieved by silicone stents as well. 21 In 17 patients treated with silicone stents after LTx, airway colonization was noted in all patients. 11 Airway colonization especially with pseudomonads was associated with an increased risk of CLAD in several publications.37–39 In our view, silicon stents are less suitable for LTx patients due to potential kinking in complex lesions, no collateral ventilation without customizing, reduced inner diameter, and high risk of colonization.

To our knowledge, there is no published data on the QoL in patients with OAC after LTx. The group from Strasbourg reported similar dyspnea grades in 22 OAC patients. 4 Airflow limitation might not be the only compound of health perception given the near only slightly reduced baseline FEV1 below the lower limit of normal in unilateral OAC patients. The burden of frequent bronchoscopies and emergency visits may represent an additional factor in reduced QoL within the first postoperative year.

The additional use of health care resources is reflected by rocketing first-year bronchoscopies in patients with bilateral OAC. A 27-year-old female cystic fibrosis patient with bilateral OAC underwent 68 bronchoscopies – most of them with interventions – within the first 11 months after LTx until finally undergoing successful re-do transplantation. The mean cost based on capital investments, repairs, and reprocessing costs of reusable bronchoscopes was calculated to be US$266. 40 In our program, 2,160 additional bronchoscopies during the 12-year period for endoscopic management of OAC patients were needed. With conservatively estimated costs of 600 Euros per bronchoscopy, including additional material for interventions (e.g. balloons) and staffing, this resulted in additional costs of almost 1.3 million Euros during that period.

The limitation of our study is a single-center design. Management of OAC is highly individualized between centers and the incidence is highly variable. The definition of OAC may vary between centers although we decided to use the pragmatic definition used in a recent publication by a similar-sized program. The ISHLT consensus is difficult to apply retrospectively, although most of our interventions were videotaped. Also, the timing for balloon dilatation and stent insertion during the management and evolution of OAC may be different between different programs. Usually, surgery for OAC is regarded as a last resort in management and it is unknown if earlier operative measures may result in better outcomes. As in other orphan procedures, there is a lack of randomized controlled trials in management.

Conclusion

Bilateral OACs impose a high burden of disease on patients after LTx. Bilateral OAC was associated with early and late graft loss, and graft colonization. Patients with bilateral OAC demonstrated significantly reduced graft function and affected patients reported a significantly impaired QoL. These complications were mostly managed endoscopically, preferably by non-permanent stenting in our study with high utilization of health care resources. Prevention of OACs is crucial.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Jens Gottlieb  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9540-9022

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9540-9022

Contributor Information

Jens Gottlieb, Department of Respiratory Medicine and Infectious Diseases OE 6870, Hannover Medical School (Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, MHH), Carl Neuberg Strasse 1, 30625 Hannover, Germany. German Center for Lung Research (DZL), Gießen, Germany.

Thomas Fuehner, Department of Respiratory Medicine, Siloah Hospital, Hannover, Germany.

Patrick Zardo, Department of Cardiothoracic, Transplantation and Vascular Surgery, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013), available at: https://www.wma.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/DoH-Oct2013-JAMA.pdf (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by institutional ethics/committee of Hannover Medical School (No 2923-2015, update September 24, 2021) and informed consent was taken from patients.

Consent for publication: Not applicable, no individual patient data.

Author contributions: Jens Gottlieb: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Thomas Fuehner: Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Patrick Zardo: Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Jens Gottlieb reports institutional research grants from Zambon/Breath Therapeutics, German Center of Lung Research, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. He also received fees for advisory/consultancy from Theravance, Pierre Fabre, Atheneum, Merck, Springer Healthcare, European Research Network, and speaker fees from Novartis, Astra Zeneca, CSL Behring. He owns stock options of Pfizer. He serves as a member of the ScanCLAD study’s data safety monitoring board. All disclosures are unrelated to the current work.

Patrick Zardo reports no disclosures.

Thomas Fuehner reports speaker fees from Novartis and Astra Zeneca.

Availability of data and materials: Anonymized participant data will be made available after publication upon requests directed to the corresponding author. Proposals will be reviewed and approved by the investigators and collaborators on the basis of scientific merit.

References

- 1. Fallis RJ, Jablonski L, Moss S, et al. Infectious complications of bronchial stenosis in lung transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 2019; 21: e13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. FitzSullivan E, Gries CJ, Phelan P, et al. Reduction in airway complications after lung transplantation with novel anastomotic technique. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92: 309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gottlieb J, Fuehner T, Dierich M, et al. Are metallic stents really safe? A long-term analysis in lung transplant recipients. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 1417–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mazzetta A, Porzio M, Riou M, et al. Patients treated for central airway stenosis after lung transplantation have persistent airflow limitation. Ann Transplant 2019; 24: 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murthy SC, Blackstone EH, Gildea TR, et al. Impact of anastomotic airway complications after lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 2007; 84: 401–9409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Patoir A, Luchez A, Tiffet O, et al. Airway complications after lung transplantation: benefit of a conservative bronchoscopy strategy. J Thorac Dis 2020; 12: 2625–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schweiger T, Nenekidis I, Stadler JE, et al. Single running suture technique is associated with low rate of bronchial complications after lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2020; 160: 1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shofer SL, Wahidi MM, Davis WA, et al. Significance of and risk factors for the development of central airway stenosis after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2013; 13: 383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Berkel V, Guthrie TJ, Puri V, et al. Impact of anastomotic techniques on airway complications after lung transplant. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92: 316–20. Discussion 320–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yserbyt J, Dooms C, Vos R, et al. Anastomotic airway complications after lung transplantation: risk factors, treatment modalities and outcome-a single-centre experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016; 49: e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dutau H, Cavailles A, Sakr L, et al. A retrospective study of silicone stent placement for management of anastomotic airway complications in lung transplant recipients: short- and long-term outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010; 29: 658–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santacruz JF, Mehta AC. Airway complications and management after lung transplantation: ischemia, dehiscence, and stenosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2009; 6: 79–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van De Wauwer C, Van Raemdonck D, Verleden GM, et al. Risk factors for airway complications within the first year after lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007; 31: 703–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weder W, Inci I, Korom S, et al. Airway complications after lung transplantation: risk factors, prevention and outcome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009; 35: 293–298. Discussion 298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kshettry VR, Kroshus TJ, Hertz MI, et al. Early and late airway complications after lung transplantation: incidence and management. Ann Thorac Surg 1997; 63: 1576–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fitzmaurice GJ, Redmond KC, Fitzpatrick DA, et al. Endobronchial cryotherapy facilitates end-stage treatment options in patients with bronchial stenosis: a case series. Ann Thorac Med 2014; 9: 120–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Madden BP, Kumar P, Sayer R, et al. Successful resection of obstructing airway granulation tissue following lung transplantation using endobronchial laser (Nd:YAG) therapy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1997; 12: 480–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wahidi MM, Unroe MA, Adlakha N, et al. The use of electrocautery as the primary ablation modality for malignant and benign airway obstruction. J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6: 1516–1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keller CA, Hinerman R, Singh A, et al. The use of endoscopic argon plasma coagulation in airway complications after solid organ transplantation. Chest 2001; 119: 1968–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abi-Jaoudeh N, Francois RJ, Oliva VL, et al. Endobronchial dilation for the management of bronchial stenosis in patients after lung transplantation: effect of stent placement on survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2009; 20: 912–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dutau H, Reynaud-Gaubert M, Thomas PA. Endoscopic management of post-lung transplantation anastomotic stenosis: metallic, silicone or biodegradable stents. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2012; 41: 1216–1217. Author reply 1267–1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuehner T, Suhling H, Greer M, et al. Biodegradable stents after lung transplantation. Transpl Int 2013; 26: e58–e60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greer M, Fuehner T, Warnecke G, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloons in refractory nonanastomostic airway stenosis following lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 2014; 14: 2400–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tendulkar RD, Fleming PA, Reddy CA, et al. High-dose-rate endobronchial brachytherapy for recurrent airway obstruction from hyperplastic granulation tissue. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 70: 701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crespo MM, McCarthy DP, Hopkins PM, et al. ISHLT consensus statement on adult and pediatric airway complications after lung transplantation: definitions, grading system, and therapeutics. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018; 37: 548–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stewart S, Fishbein MC, Snell GI, et al. Revision of the 1996 working formulation for the standardization of nomenclature in the diagnosis of lung rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant 2007; 26: 1229–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011; 20: 1727–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 319–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, et al. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Eur Respir J 1993; 6(Suppl. 16): 5–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Verleden GM, Glanville AR, Lease ED, et al. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: definition, diagnostic criteria, and approaches to treatment –a consensus report from the pulmonary council of the ISHLT. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019; 38: 493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu J, Jackson K, Weinkauf J, et al. Baseline lung allograft dysfunction is associated with impaired survival after double-lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018; 37: 895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Awori Hayanga JW, Aboagye JK, Shigemura N, et al. Airway complications after lung transplantation: contemporary survival and outcomes. J Heart Lung Transplant 2016; 35: 1206–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gottlieb J, Fuehner T, Greer M. Biodegradable stent for vanishing bronchus syndrome after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36: 591–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fakhro M, Ingemansson R, Algotsson L, et al. Impact of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and 6-minute walking distance at 3, 6, and 12 months and annually on survival and occurrence of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) after lung transplantation. Ann Transplant 2017; 22: 532–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Paraskeva MA, Borg BM, Paul E, et al. Abnormal one-year post-lung transplant spirometry is a significant predictor of increased mortality and chronic lung allograft dysfunction. J Heart Lung Transplant 2021; 40: 1649–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burton CM, Iversen M, Mortensen J, et al. Post-transplant baseline FEV1 and the development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: an important confounder? J Heart Lung Transplant 2007; 26: 1127–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Botha P, Archer L, Anderson RL, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization of the allograft after lung transplantation and the risk of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Transplantation 2008; 85: 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gottlieb J, Mattner F, Weissbrodt H, et al. Impact of graft colonization with gram-negative bacteria after lung transplantation on the development of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in recipients with cystic fibrosis. Respir Med 2009; 103: 743–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vos R, Vanaudenaerde BM, De Vleeschauwer SI, et al. De novo or persistent pseudomonal airway colonization after lung transplantation: importance for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome? Transplantation 2008; 86: 624–625. Author reply 635–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Andersen CØ, Travis H, Dehlholm-Lambertsen E, et al. The cost of flexible bronchoscopes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacoecon Open 2022; 6: 787–797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]