Abstract

Vaccinia virus nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I (NPH-I) is a DNA-dependent ATPase that serves as a transcription termination factor during viral mRNA synthesis. NPH-I is a member of the DExH box family of nucleic acid-dependent nucleoside triphosphatases (NTPases), which is defined by the presence of several conserved sequence motifs. We have assessed the contributions of individual amino acids (underlined) in motifs I (GxGKT), II (DExHN), III (SAT), and VI (QxxGRxxR) to ATP hydrolysis by performing alanine scanning mutagenesis. Significant decrements in ATPase activity resulted from mutations at nine positions: Lys-61 and Thr-62 (motif I); Asp-141, Glu-142, His-144, and Asn-145 (motif II); and Gln-472, Arg-476, and Arg-479 (motif VI). Structure-function relationships at each of these positions were clarified by introducing conservative substitutions and by steady-state kinetic analysis of the mutant enzymes. Comparison of our findings for NPH-I with those of mutational studies of other DExH and DEAD box proteins underscores similarities as well as numerous disparities in structure-activity relationships. We conclude that the functions of the conserved amino acids of the NTPase motifs are context dependent.

Members of the DExH family of nucleic acid-dependent nucleoside triphosphatases (NTPases) contain six conserved motifs arrayed in a collinear fashion (7). The number of DExH proteins is increasing rapidly as the signature elements are encountered during genome sequencing. The DExH box proteins are often designated as putative helicases, yet only a subset of these nucleic acid-dependent NTPases are actually able to unwind duplex DNA or RNA in vitro.

The vaccinia virus enzymes nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I (NPH-I) and NPH-II were the first DExH box NTPases to be purified and characterized (20, 21). NPH-II, a 676-amino-acid monomer, is a nucleoside triphosphate (NTP)-dependent 3′-to-5′ RNA helicase (10, 26, 27). NPH-II hydrolyzes any NTP or dNTP, and its NTPase activity is stimulated 10- to 40-fold by either single-stranded DNA or RNA (8, 21). NPH-II exemplifies a subgroup of structurally related DExH proteins that includes human RNA helicase A; the yeast pre-mRNA splicing factors Prp2, Prp16, and Prp22; Drosophila maleless; and hepatitis C virus RNA helicase NS3 (9).

Vaccinia virus NPH-I, a 631-amino-acid monomeric protein, catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATP and dATP only, and its activity is absolutely dependent on a single-strand DNA cofactor (1, 5, 20, 21, 25). NPH-I is a component of the vaccinia virus RNA polymerase transcription elongation complex and serves as a transcription termination factor during the synthesis of viral early mRNAs (4, 5). Release of the transcript from the elongation complex requires ATP hydrolysis by NPH-I (3, 5). Attempts to demonstrate a helicase function for NPH-I have been unsuccessful. NPH-I is the prototype member of a distinct subgroup of DExH proteins that includes Snf2 and its numerous homologues (13). Snf2-like proteins are implicated in transcriptional activation and repression and in chromatin remodeling (24). As with NPH-I, most Snf2-like proteins do not score positively when assayed for helicase activity in vitro.

Our aim was to delineate structure-function relationships for DExH box proteins that would provide insights into the mechanism of nucleic acid-dependent NTP hydrolysis and, where applicable, the coupling of phosphohydrolase activity to duplex unwinding. We previously reported the effects of alanine substitution mutations in NPH-II (8, 9, 11). This analysis revealed that amino acids (underlined) in motifs I (GxGKT), II (DExHE), and VI (QRxGRxGR) are important for NTP hydrolysis. That the NTPase-defective mutants were also defective in RNA unwinding confirms the dependence of strand displacement on NTP hydrolysis. A distinct class of mutations, involving the threonines in motif III (TAT) and the histidine moiety of the DExH box, elicited defects in RNA unwinding but spared the NTPase function (8, 11). Thus, certain moieties are required to couple energy generation to strand displacement.

In the present study, we initiated a mutational analysis of vaccinia virus NPH-I with the intent of establishing structure-function relationships for the Snf2-like ATPase subfamily. An alanine scan of 12 residues in NPH-I motifs I, II, III, and VI identified 9 amino acids that are important for ATP hydrolysis. By introducing conservative substitutions at these positions, we defined the essential functional groups. Comparison of our mutagenesis results for NPH-I with those reported for other DExH or DEAD box proteins underscores the fact that structure-function relationships at conserved residues in the motifs are context dependent; i.e., mutational effects on one nucleic acid-dependent NTPase cannot be extrapolated to other proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Missense mutants of NPH-I.

Plasmid pET-His-NPH-I encodes the 631-amino-acid NPH-I polypeptide fused to an N-terminal leader peptide containing 10 tandem histidines (5). Expression of this protein is under the control of a T7 RNA polymerase promoter. Missense mutations were introduced into the NPH-I gene by PCR, using the two-stage overlap extension method. Residues targeted for amino acid substitutions were Lys-61 and Thr-62 (motif I); Asp-141, Glu-142, His-144, and Asn-145 (motif II); Ser-183 and Thr-185 (motif III); and Gln-472, Gly-475, Arg-476, and Arg-479 (motif VI). The mutated DNA products of the second-stage amplification were either digested with NdeI and BglII and inserted into pET16b or else restricted with NdeI and BamHI and inserted into pET-His-NPH-I in lieu of the corresponding wild-type restriction fragment. The presence of the desired mutations was confirmed by DNA sequencing; the segment corresponding to the inserted restriction fragment was sequenced completely in order to exclude acquisition of unwanted mutations during amplification and cloning.

Carboxyl-terminal truncations of NPH-I.

Carboxyl-terminal truncation mutants were constructed by PCR amplification with antisense primers that introduced translation stop codons in lieu of the codons for Tyr-604, Ile-563, Asp-545, Lys-532, Lys-522, and Glu-511 and BglII sites immediately 3′ of the new stop codons. The PCR products were digested with NdeI and BglII and then inserted into pET16b. The truncated NPH-I genes and proteins were named according to the number of amino acids deleted from the C terminus, i.e., Δ28, Δ69, Δ87, Δ100, Δ110, and Δ121.

NPH-I expression and purification.

The NPH-I expression plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). Transformants were inoculated into Luria-Bertani medium containing 0.1 mg of ampicillin/ml and grown at 37°C until the A600 reached approximately 0.6. Cultures (1 liter each) were then placed on ice for 30 min, ethanol was added to a final concentration of 2%, and the cultures were subsequently incubated at 18°C for 24 h with continuous shaking. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, and the pellets were stored at −80°C. All subsequent procedures were performed at 4°C. The cells were thawed and resuspended in 80 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.5], 0.15 M NaCl, 10% sucrose) containing 0.2 mg of lysozyme/ml. After 30 min on ice, Triton X-100 was added to the suspensions to a final concentration of 0.1%. The lysates were sonicated to reduce their viscosity. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation for 40 min at 18,000 rpm in a Sorvall SS-34 rotor. The supernatants were mixed with 1 ml of Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose resin (Qiagen) for 1 h. The slurries were poured into columns, which were eluted serially with IMAC buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 0.5 M NaCl, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10% glycerol) containing 5, 25, 50, and 200 mM imidazole. The polypeptide composition of the column fractions was monitored by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Fractions enriched for the expressed NPH-I polypeptide (which eluted at 200 mM imidazole) were pooled and dialyzed against 0.5× buffer A (1× buffer A contains 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1% Triton X-100, and 10% glycerol). The dialysates were applied to 1-ml columns of phosphocellulose that had been equilibrated with 0.5× buffer A. The columns were eluted stepwise with 1× buffer A containing 50, 100, and 500 mM NaCl. The NPH-I proteins were recovered in the 500 mM NaCl eluate fractions.

Determination of NPH-I protein concentration.

Aliquots (1× and 2×) of each phosphocellulose NPH-I preparation were analyzed by SDS-PAGE in parallel with a twofold dilution series of bovine serum albumin (BSA; from 0.125 to 4 μg per lane). The gels were stained with Coomassie blue dye. The staining intensities of the polypeptides were quantitated with a digital imaging and analysis system (Alpha Innotech Corporation). NPH-I concentrations were calculated by extrapolation to the BSA standard curve.

ATPase assay.

ATPase activity was determined by the release of 32Pi from [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of a DNA cofactor. Reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM [γ-32P]ATP, 1 μg of heat-denatured herring sperm DNA, and NPH-I were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. An aliquot (2 μl) of the reaction mixture was applied to a polyethyleneimine-cellulose thin-layer chromatography plate that was developed in 0.5 M LiCl–1 M formic acid. [γ-32P]ATP and 32Pi were quantitated by scanning the thin-layer chromatography plate with a FUJIX model BAS2500 Bio-Imaging Analyzer.

Western blot analysis.

Aliquots (20 ng) of purified wild-type NPH-I and C-terminal truncation mutants of NPH-I were electrophoresed through a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% SDS, and the polypeptides were transferred electrophoretically to a nitrocellulose membrane. After preincubation with a solution consisting of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 5% (wt/vol) BSA, and 1% (wt/vol) powdered milk, the membrane was incubated for 2 h at 22°C with rabbit anti-NPH-I serum diluted 1:1,500 in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–150 mM NaCl. The membrane was washed with a solution containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, and 0.4% Tween 20 and then incubated for 1 h with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. The immunoreactive polypeptides were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (ECL; Amersham) in accordance with the instructions of the vendor. The anti-NPH-I serum was a gift of E. G. Niles, State University of New York at Buffalo.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis strategy.

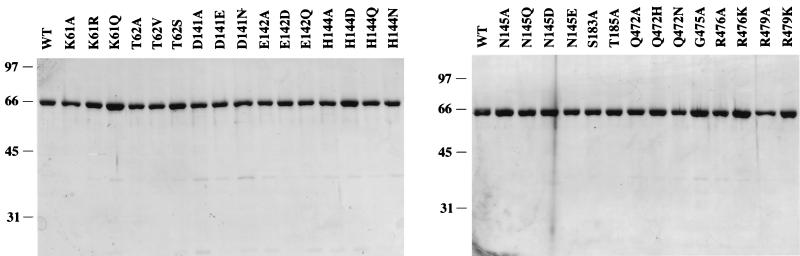

Alanine mutations were introduced in lieu of 12 residues (underlined) within motifs I (58-GVGKT-62), II (141-DECHN-145), III (183-SAT-185), and VI (472-QIVGRAIR-497) of vaccinia virus NPH-I. Wild-type NPH-I and the NPH-I Ala mutants were expressed in bacteria as N-terminal His-tagged fusion proteins and then purified from soluble bacterial lysates by Ni-agarose and phosphocellulose column chromatography (5). Initial assessment of the DNA-dependent ATPase activity of the NPH-I Ala mutant proteins revealed significant activity decrements for nine of the mutants. (We define a 1-order-of-magnitude decrement in ATPase specific activity as the threshold of significance.) Conservative amino acid substitutions were then introduced for these nine residues, and the mutants enzymes were expressed in bacteria and purified. SDS-PAGE analysis of wild-type NPH-I and 30 different NPH-I mutants showed that the phosphocellulose preparations were highly enriched with respect to NPH-I and that the extents of purification were similar (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

NPH-I purification. Aliquots (1 μg) of the phosphocellulose preparations of wild-type (WT) NPH-I and the indicated NPH-I mutants were electrophoresed through 10% polyacrylamide gels containing 0.1% SDS. Polypeptides were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue dye. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of marker proteins are indicated at the left of each gel.

DNA-dependent ATPase activity.

Recombinant wild-type NPH-I catalyzed the release of 32Pi from [γ-32P]ATP in the presence of magnesium and single-stranded DNA. The extent of ATP hydrolysis was linear with respect to the level of input enzyme at limiting concentrations, and the reaction proceeded to completion at saturating enzyme levels (5). The specific activity of wild-type NPH-I in the presence of 1 mM ATP, 1 mM MgCl2, and 100 μg of denatured DNA/ml was 7.8 nmol of ATP hydrolyzed per ng of protein in 30 min. Assuming that all NPH-I molecules are active, this value translates into a turnover number of ∼320 s−1. ATP hydrolysis was undetectable in the absence of either magnesium or single-stranded DNA (18). Recombinant wild-type NPH-I was unable to hydrolyze GTP in place of ATP (18).

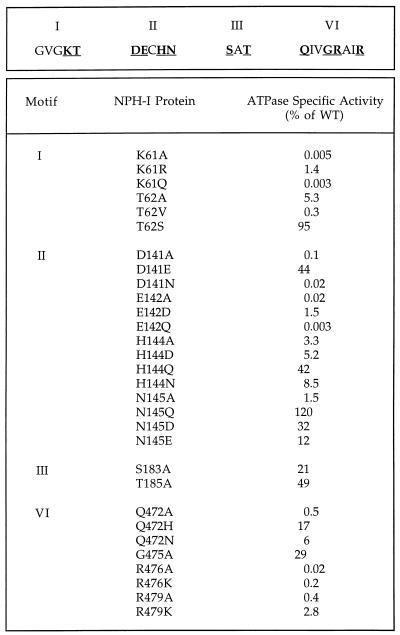

The specific ATPase activities of 30 different NPH-I mutants were determined by enzyme titration. The findings are summarized in Fig. 2, where the ATPase activities of the mutants are expressed as percentages of wild-type NPH-I’s specific activity. Twenty of 30 mutations caused significant reductions in activity. The observed effects on DNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis were unlikely to be caused by a DNA binding defect because (i) the DNA cofactor concentration in the ATPase reaction mixtures was 10 times in excess of that required for peak ATP hydrolysis by wild-type NPH-I; and (ii) each of the NPH-I mutants retained the capacity to bind single-stranded DNA, as gauged by a native-gel electrophoretic mobility shift assay (18). Each of the mutant enzymes was tested for the DNA dependence of its ATPase activity. None of the mutations conferred the capacity to hydrolyze ATP in the absence of a single-strand DNA cofactor. The mutants were also tested for their ability to hydrolyze GTP in the presence of single-strand DNA; none was able to do so. Thus, there were no obvious gain-of-function effects elicited by the mutations.

FIG. 2.

DNA-dependent ATPase activities of NPH-I mutants. The sequences of motifs I, II, III, and VI are shown. (Top) Motif amino acids residues subjected to mutational analysis are underlined and in boldface. (Bottom) ATPase activity was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. Aliquots (2 μl) of serial twofold dilutions of each phosphocellulose enzyme preparation were included in the reaction mixtures. Between two and four titration experiments were performed for each mutant protein, and the specific activities were calculated from the averages of the slopes of the titration curves. The ATPase specific activities shown are normalized to the specific activity of wild-type (WT) NPH-I.

Structure-function relationships for motif I.

Motif I corresponds to the Walker A box, GxGK(T/S), which is common to many proteins that bind and hydrolyze NTPs. We found that replacement of the NPH-I motif I lysine (Lys-61) by alanine elicited a >10−4 decrement in ATPase activity. Glutamine at this position reduced activity to the same extent (Fig. 2). The ATPase function was restored partially when Lys-61 was replaced by arginine (K61R). Although the K61R mutant enzyme was only 1.4% as active as wild-type NPH-I, it was nonetheless >100-fold more active than the K61A or K61Q mutant. These data establish a clear requirement for a positively charged residue, specifically lysine, at this critical position. To gain further insights into the function of the motif I lysine, we determined the Km for ATP of wild-type NPH-I and the K61R mutant. ATP hydrolysis was measured as a function of ATP concentration in the presence of single-stranded DNA and 5 mM MgCl2. The affinity of the K61R mutant for ATP (Km = 0.39 mM) was similar to that of wild-type NPH-I (Km = 0.43 mM), but the Vmax of K61R was 1.4% of the wild-type value (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters for ATP hydrolysisa

| NPH-I protein | Km, ATP (mM) | Vmax (% of WT) |

|---|---|---|

| WT | 0.43 | 100 |

| K61R | 0.39 | 1.4 |

| D141E | 0.40 | 60 |

| E142D | 0.18 | 2 |

| H144Q | 0.53 | 71 |

| N145Q | 1.0 | 326 |

| Q472H | 0.63 | 29 |

| Q472N | 0.48 | 7 |

| R479K | 1.8 | 5 |

DNA-dependent ATPase activity was measured as a function of ATP concentration. Reaction mixtures (10 μl) containing 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 μg of heat-denatured herring sperm DNA, various concentrations of [γ-32P]ATP, and enzyme were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Kinetic parameters were calculated from double-reciprocal plots of each titration series. Vmax is expressed relative to that of the wild-type (WT) enzyme (100% = 300 s−1).

Replacement of the motif I threonine (Thr-62) by alanine reduced ATPase activity to 5.3% of the wild-type level. Substitution of valine (which is sterically similar to threonine) for Thr-62 was even more deleterious than the alanine change, reducing activity to 0.3% of the wild-type level. We surmise that this is caused by the hydrophobic character of the side chain. ATPase activity was restored fully when Thr-62 was replaced by serine. Hence, the hydroxyl moiety is critical for the function of this residue. The ATPase activity of the T62A mutant increased linearly with the ATP concentration up to 4 mM (data not shown). Thus, the T62A mutant displayed at least a 10-fold increase in Km compared to wild-type NPH-I and the K61R mutant. Although we did not determine the Vmax (because of a failure to attain saturation), from the ATP titration we can extrapolate that the activity of T62A at 4 mM ATP was 21% of the Vmax for wild-type NPH-I.

These results imply that the NPH-I motif I lysine functions in phosphohydrolase reaction chemistry and that the motif I threonine functions in ATP binding. The motif I lysine and threonine residues are also essential for the nucleic acid-dependent ATPase activity of vaccinia virus NPH-II (11).

Structure-function relationships for motif II.

Replacement of Asp-141 of motif II by alanine reduced the ATPase activity by 3 orders of magnitude. Similar effects were seen when Asp-141 was replaced by asparagine. Activity was restored to about half the wild-type value when glutamate was introduced (Fig. 2). The D141E mutation did not affect the Km for ATP, and the Vmax was 60% of the wild-type value (Table 1). An acidic side chain at this position is clearly essential for catalysis, and there is no significant steric constraint that precludes replacement of Asp-141 by the larger glutamate side chain.

Mutation of Glu-142 to either alanine or glutamine resulted in a >10−3 decrement in specific activity, but in this case activity was restored to only 1.5% of the wild-type value when aspartic acid was introduced in lieu of Glu-142. We surmise that ATP hydrolysis requires a minimal distance of the acidic functional group from the main chain that cannot be met by the shorter aspartic acid side chain.

Replacement of the histidine moiety of motif II by alanine reduced the specific activity to 3.3%; similar reductions were seen when His-144 was changed to aspartic acid (5.2%) or asparagine (8.5%). However, a restoration of ATPase activity to 42% of the wild-type level was noted when glutamine was introduced at this position (Fig. 2). The kinetic parameters of the H144Q enzyme were close to those of wild-type NPH-I (Table 1). However, the phosphohydrolase activity of the H144A, H144N, and H144D proteins increased linearly with the ATP concentration up to 4 mM (data not shown). As noted above for T62A, this behavior is indicative of a much-diminished affinity for ATP. At 4 mM ATP, the specific activities of H144A, H144N, and H144D were 6.3, 13, and 23% of the wild-type Vmax. Asparagine and glutamine are partially isosteric with histidine, such that the amide nitrogens of Asn and Gln can be imposed on Nδ and Nɛ of His, respectively. The mutational findings at His-144 of NPH-I suggest that Nɛ is the relevant moiety involved in ATP binding.

Changing Asn-145 of NPH-I motif II to alanine reduced the ATPase activity to 1.5% of the wild-type value. Introduction of glutamate and aspartate restored activity to 12 and 32% of the wild-type level, respectively (Fig. 2). Mutating Asn-145 to glutamine resulted in a enzyme with a higher specific activity than that of the wild type. These results suggest that a polar side chain is important at this position. The phosphohydrolase activity of the N145A mutant increased linearly with ATP concentration up to 4 mM (data not shown), again indicative of a reduced binding affinity for ATP. The activity of the N145A enzyme at 4 mM ATP was 5.3% of the wild-type Vmax. The N145Q mutation resulted in a modest increase in Km (to 1 mM) and a threefold increase in Vmax compared to wild-type NPH-I.

Motif III side chains are not essential for ATP hydrolysis by NPH-I.

Alanine substitutions at Ser-183 and Thr-185 of the SAT motif in NPH-I reduced the ATPase activity to 21 and 49% of the wild-type level, respectively (Fig. 2). These modest effects did not meet the criterion of a 10-fold activity decrement that we had set for designating a given side chain as being important for ATP hydrolysis.

Structure-function relationships for motif VI.

Replacement of Gln-472 by alanine lowered the ATPase activity to 0.5% of the wild-type value. Conservative changes to asparagine and histidine restored the specific activity to 6 and 17%, respectively, of that of the wild type. The Q472N and Q472H mutations reduced the Vmax values to 7 and 29% of that of the wild type, respectively, with little effect on the Km for ATP (Table 1). These findings suggest that the essential function of Gln-472 entails hydrogen bonding interactions with the amide moiety that are sensitive to its distance from the main chain.

Changing Arg-476 to alanine reduced the ATPase activity by more than 3 orders of magnitude; alanine in lieu of Arg-479 lowered this activity to 0.4% of the wild-type level. The conservative mutants R476K and R479K were also defective, with only 0.2 and 2.8% of the specific activity of wild-type NPH-I (Fig. 2). Hence, there is a strict requirement for arginine at both positions. The R479K mutation resulted in a reduced affinity for ATP (Km = 1.8 mM) and a 20-fold decrement in the Vmax (Table 1).

Replacement of Gly-475 by alanine resulted in only an approximately threefold decrease in specific activity; hence, this residue is not important for ATP hydrolysis. We presume that a bulkier side chain at this position affects activity indirectly via subtle changes in the conformation of other essential side chains within motif VI.

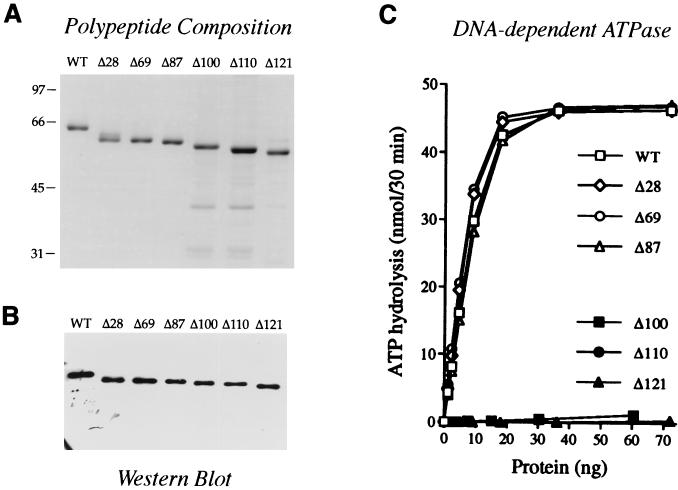

Carboxyl truncations of NPH-I define a minimal ATPase domain.

A set of six carboxyl-terminal truncation mutants of NPH-I (named Δ28, Δ69, Δ87, Δ100, Δ110, and Δ121, according to the number of C-terminal amino acids deleted) were expressed in E. coli with N-terminal His tags and then purified from soluble bacterial lysates by Ni-agarose and phosphocellulose column chromatography. SDS-PAGE analysis indicated that the phosphocellulose preparations were highly enriched with respect to the NPH-I polypeptides (Fig. 3A). Western blotting with anti-NPH-I antiserum confirmed that the predominant polypeptide in the enzyme preparations corresponded to NPH-I (Fig. 4B). The specific ATPase activities of the Δ28, Δ69, and Δ87 proteins were essentially identical to that of full-length wild-type NPH-I, whereas Δ100, Δ110, and Δ121 were catalytically inactive (Fig. 4C). This experiment defines a catalytically active ATPase domain (Δ87) from amino acids 1 to 544 that includes all of the conserved motifs. Our findings confirm and refine the C-terminal deletion analysis of Christen et al. (3), who noted that NPH-I residues 1 to 563 were sufficient for ATP hydrolysis whereas a derivative containing residues 1 to 524 was inactive. We suspect that mutants with C-terminal deletions beyond Δ87 may be defective by virtue of improper protein folding, because whereas the catalytically active Δ87 enzyme sedimented as a discrete monomer in a glycerol gradient, the inactive Δ100 polypeptide sedimented diffusely in fractions of larger than monomer size (data not shown). This suggested that the recombinant Δ100 protein formed nonspecific aggregates. Similar results were obtained for Δ121. We eschewed N-terminal deletion analysis of NPH-I in light of the close proximity of essential motif I to the amino terminus.

FIG. 3.

Carboxyl-terminal truncation mutants of NPH-I. (A) Polypeptide composition. Aliquots (0.3 μg) of the phosphocellulose preparations of wild-type (WT) NPH-I and the indicated C-terminal truncation mutants were electrophoresed through a 10% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% SDS. Polypeptides were visualized by staining with Coomassie blue dye. The positions and sizes (in kilodaltons) of marker proteins are indicated at the left of each gel. (B) Western blotting was performed as described in Materials and Methods. (C) DNA-dependent ATPase activities. Reaction mixtures (50 μl) containing 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 1 mM [γ-32P]ATP, 1 μg of heat-denatured DNA, and enzyme as specified were incubated for 30 min at 37°C.

DISCUSSION

Here we have presented an analysis of the role of conserved motifs I, II, III, and VI in DNA-dependent ATP hydrolysis by vaccinia virus NPH-I. Our characterization of 30 different mutant enzymes is the most extensive in vitro structure-function study of a DExH protein to date and the first to address in detail the requirements for ATP hydrolysis by an Snf2-like enzyme. Mutational analyses of motifs I, II, III, and VI have also been performed for vaccinia virus NPH-II (8, 9, 11) and hepatitis C virus NS3 (12, 15) (both of which are DExH box NTPases/helicases), for the yeast DExH box splicing factor Prp16 (this analysis, described in reference 14, was confined to in vivo mutational effects), and for the mammalian DEAD box ATPase eIF4A (22, 23). In the following sections, we review and compare the mutagenesis results for these DEAD or DExH box proteins and interpret them in light of the recently reported crystal structures of several nucleic acid-dependent NTPases.

Motif I.

High-resolution crystallographic studies of H-ras p21 showed that the invariant lysine of the Walker A motif makes direct contact with the β- and γ-phosphates of the bound nucleotide (19). Hence, this lysine has been mutated in numerous NTPases. Our finding that the K61A mutation of vaccinia virus NPH-I abrogates NTP hydrolysis agrees with the effects of mutations at the corresponding lysines in eIF-4A (23), NPH-II (11), Prp16 (14), RAD3 (30), PriA (32), and UvrD (6). The K61Q and K61R mutants were also catalytically defective. Kinetic analysis of the K61R mutant showed a severe decrement in the Vmax with no significant effect on the Km for ATP. This argues for an essential role of the motif I lysine in catalysis but not in ATP binding. Similar conclusions were drawn from studies of motif I mutants of Rad3 (a Lys-to-Arg mutant) and UvrD (a Lys-to-Met mutant) (6, 30). In contrast, in the case of eIF4A, mutation of the motif I lysine to asparagine abolished ATP binding as well as ATP hydrolysis (23). Remarkably different effects were reported by Kim et al. (15) for a mutant of hepatitis C virus NS3 in which the lysine was replaced by glutamic acid; they found that the Lys-to-Glu mutant retained NTPase activity (at 29 to 39% of the specific activity of wild-type NS3) and actually had a sixfold-lower Km for ATP than the wild-type enzyme. Lys-to-Glu and Lys-to-Ala mutations of yeast Prp16 are lethal in vivo: however, an arginine at this position supports cell growth (14).

Three different groups have reported crystal structures for hepatitis C virus NS3, which is the only member of the DExH family for which structural information is available (2, 16, 31). The NS3 protein is a Y-shaped molecule consisting of three structural domains. Domain 1 (containing motifs I and II) and domain 2 (containing motif VI) comprise the two prongs of the Y and are separated by an interdomain cleft. In two of the structures of unliganded NS3, the motif I lysine forms a salt bridge with the aspartic acid of the DExH box (2, 31). In the structure of NS3 bound to a single-stranded oligonucleotide, a sulfate ion is coordinated at the position predicted to be occupied by the β-phosphate of the NTP substrate (16). In the NS3-oligonucleotide cocrystal, the motif I lysine (Lys-210) side chain forms a hydrogen bond with the sulfate and makes an additional water-mediated contact with the Asp of the DExH box (16). The mutational data of Kim et al. (15) are difficult to reconcile with the structural data for NS3, given that glutamate is unlikely to interact like lysine does with the nucleotide phosphate(s) or the motif II aspartate.

The amino acid adjacent to the motif I lysine is either threonine or serine. In NPH-I, serine is fully active in lieu of Thr-62 whereas the alanine and valine mutants are catalytically defective. The motif I threonine of vaccinia virus NPH-II is also essential for NTP hydrolysis (11). Yeast Prp16 is active in vivo when the motif I threonine is replaced by serine, but the alanine and valine mutations are lethal (14). Clearly, the hydroxyl group is critical for function in these three cases. To our knowledge, the effects of mutations in the motif I serine of NS3 or the motif I threonine of eIF4A have not been reported. In the NS3-oligonucleotide cocrystal, the hydroxyl moiety of the motif I serine (Ser-211) forms a hydrogen bond with the enzyme-bound sulfate, which presumably reflects its normal interaction with the NTP β-phosphate. Structures have been reported for other helicases (E. coli Rep and Bacillus stearothermophilus PcrA) and NTPases (RecA and H-ras p21) with bound nucleotides (17, 19, 28, 29). In H-ras p21 bound to GMPPNP, the serine hydroxyl in the GKS element interacts with the β-phosphate and with magnesium coordinated to the β- and γ-phosphates (19). Similar contacts are proposed for the GKT motif in the RecA-ADP cocrystal (28). The motif I threonine side chain of the Rep- and PcrA-ADP complexes are also poised near the β-phosphate (17, 29). Our kinetic analysis of the T62A mutant of NPH-I argues that the hydroxyl-containing side chain contributes to ATP binding affinity.

Motif II.

The aspartic acid residue in the Walker B motif of the p21 structure (equivalent to the Asp in the DExH box) interacts via a water molecule with the magnesium ion (19). The aspartate residue of the PcrA DExx box is located near the bound ADP (29). As noted above, this aspartate side chain of NS3 forms a salt bridge with the motif I lysine side chain in the unliganded enzyme. The putative metal-binding and lysine-interacting functions of this residue can be mediated by either Glu or Asp in NPH-I. An asparagine side chain, which would not be expected to fulfill either role, is unable to support the ATPase activity of NPH-I. An Asp-to-Glu change in eIF4A has little effect on the Km or Vmax of the ATPase (but, interestingly, this mutation abolishes RNA unwinding by eIF4A). An NEAD mutation of the DEAD box of eIF4A abolishes ATP hydrolysis without affecting ATP binding (23). In Prp16, the EEAH mutant is viable whereas AEAH and NEAH mutations are lethal (14). The Asp side chain of NPH-II is also important for ATP hydrolysis (8). Thus, the mutational effects at this position are concordant among NPH-I, eIF4A, Prp16, and NPH-II.

The glutamate side chain of the NPH-I DExH box is strictly essential for ATP hydrolysis; its mutation to aspartic acid reduces the Vmax by a factor of 50 without diminishing the affinity for ATP. In the crystal structures of Rep and PcrA complexed with ADP, the glutamate residue of the DExx box is located near the ADP nucleotide in the same position in space as Glu-96 of RecA, which has been proposed to serve as a general base to activate water during the attack on the γ-phosphate (17, 28, 29). The observation that the function of the glutamic acid of NPH-I cannot be fulfilled by glutamine is consistent with its function as a general base catalyst. The analogous DQAD mutation in the DEAD box of eIF4A abolished ATP hydrolysis without affecting ATP binding (23). The motif II glutamate is also important for ATP hydrolysis by vaccinia virus NPH-II (8). In Prp16, aspartic acid can function in lieu of the motif II glutamate (unlike in NPH-I), whereas alanine and glutamine mutations are lethal (14). There appears to be a generic requirement for an acidic side chain at this position, although constraints on the distance of the carboxylate from the main chain may vary among the DExH family members.

The histidine moiety of the DExH box is important for ATP hydrolysis by NPH-I; replacement by alanine reduced the ATPase specific activity to 3.3% of the wild-type value and significantly diminished enzyme affinity for ATP. The ATPase activity of the NPH-I H144A mutant was completely dependent on the presence of a single-stranded DNA cofactor. These results contrast sharply with the mutational effects at this position seen with other nucleic acid-dependent NTPases. For example, the DExA mutation of NPH-II elicits a gain of function, whereby the mutant enzyme hydrolyzes ATP in the absence of a nucleic acid cofactor nearly as well as the wild-type NPH-II hydrolyzes this NTP in the presence of nucleic acid (8). The DExA mutation of NPH-II increases the Vmax for the nucleic acid-independent ATPase but has no effect on the Km for ATP. Heilek and Peterson (12) found that the ATPase activity of the DExA mutant of hepatitis C virus NS3 was higher than that of wild-type NS3. Kim et al. (15) noted that the DExA mutant of NS3 constitutively hydrolyzed NTPs in the absence of nucleic acid with a higher specific activity than wild-type NS3 in the presence of nucleic acid. Pause and Sonenberg (23) reported that changing the DEAD box of eIF4A to DEAH resulted in a threefold increase in the Vmax for ATP hydrolysis with no effect on Km. The DEAA mutant of Prp16 is fully functional in vivo (14). Clearly, the histidine of the DExH box plays distinct roles in ATP hydrolysis for different family members.

In the NS3 structure, the DExH box histidine can hydrogen bond via Nδ to the threonine of the TAT motif (2) and can also interact across the interdomain cleft with the essential glutamine of motif VI (16). It is likely that the motif II histidine-motif III threonine interaction contributes to the coupling of NTP hydrolysis to duplex unwinding by those DExH proteins that have helicase activity (8, 12). In NPH-I, which has no detectable helicase activity, we suspect that a putative histidine-motif VI glutamine interaction (inferred from the NS3 structure) facilitates ATP hydrolysis. It is not clear if the effects of the DExA mutation on the affinity of NPH-I for ATP are direct (implying contact between histidine and ATP) or are an indirect effect of altered contacts within the enzyme.

The asparagine adjacent to the DExH box histidine of vaccinia virus NPH-I is also important for ATP hydrolysis. Replacement of the asparagine by alanine inhibits the ATPase of NPH-I, but the fact that activity is restored by glutamine, and to a lesser extent by glutamate or aspartate, suggests that any polar side chain may suffice. This residue is conserved as an asparagine in the NPH-I homologues encoded by molluscum contagiosum virus and fowlpox virus and in other DExH box proteins, including the D6 ATPase subunit of vaccinia virus early transcription initiation factor and yeast RAD3. Yet, this position is occupied by a lysine in the NPH-I of insect poxviruses and by arginine in Snf2. The analogous residue of vaccinia virus NPH-II is glutamic acid (E300), and mutation of this residue to alanine reduced the ATPase specific activity to 1% of the level of wild-type NPH-II (11). This effect is of the same magnitude as the N145A mutation in NPH-I. In contrast, substitution of alanine for the analogous glutamate of Prp16 had no effect on its function in vivo (14).

Motif III.

Motif III of the hepatitis C virus NS3 protein is a flexible linker connecting domains 1 and 2 (31). In NPH-I, neither the serine nor the threonine of motif III is essential for ATP hydrolysis; i.e., replacement with either of these amino acids elicited only a modest decrement in specific activity. Analogous mutations to alanine in the TAT motif of NPH-II also caused a modest (twofold) decrement in DNA-dependent ATPase activity (11). Changing the SAT motif of eIF4A to AAA actually increased the ATPase activity twofold relative to that of the wild-type enzyme (23). Motif III mutants of NPH-II and eIF4A inhibit helicase function even though ATP hydrolysis is preserved. Distinctive effects were reported for the AAT mutation of NS3, which had no effect on the ATPase activity in the absence of nucleic acid but prevented an increase in ATP hydrolysis in response to an RNA cofactor, even though the AAT mutant bound RNA with wild-type affinity (15). The NS3 AAT mutant had 50% of the helicase activity of the wild-type enzyme. It has been suggested that motif III mediates conformational changes coordinated with the ATPase reaction cycle. Helicases like NPH-II and eIF4A may couple the NTP-driven conformational changes to strand separation, whereas NPH-I- and Snf2-like proteins may use NTP-derived energy to effect other macromolecular rearrangements. NPH-I’s function in transcription termination depends on its ability to hydrolyze ATP (3–5). The T185A mutation of motif III, which preserves ATP hydrolysis, also preserves the termination factor activity (3). Hence, motif III may not be critical for the biological function of NPH-I. This appears to be the case for Prp16 also, because mutations to alanine in the SAT motif result in functional proteins in vivo (14).

Motif VI.

Substitutions with alanine showed that the one glutamine and two arginine side chains of motif VI (QxxGRxxR) are essential for ATP hydrolysis by NPH-I. These three amino acids are conserved throughout the DExH family. In the DEAD box proteins, the first position of motif VI is a histidine rather than a glutamine. It is interesting that the Q472H mutant of NPH-I retains substantial ATPase activity (29% of the wild-type Vmax), as does the reciprocal His-to-Gln mutation in motif VI of eIF4A (23% of the wild-type Vmax) (23). Similarly, the Gln-to-His mutant of Prp16 is functional in vivo, although the alanine substitution is lethal (14). In contrast, the Gln-to-His mutation in motif VI of NS3 completely abolishes NTPase activity (15).

Both arginines in the QxxGRxxR motif are essential for ATP hydrolysis by NPH-I. The finding that neither Arg-476 nor Arg-479 of NPH-I can be replaced by lysine suggests that the arginines make bidentate contacts, possibly with the phosphate oxygens of ATP. In the NS3-oligonucleotide cocrystal, the motif VI arginine side chains Arg-464 and Arg-467 (equivalent to Arg-476 and Arg-479 of NPH-I) extend into the interdomain cleft and are predicted to interact with the ATP γ- and α-phosphate, respectively (16). The NS3 R464A and R467K mutations abrogate nucleic acid-dependent NTP hydrolysis (15). Prp16 also displays a stringent requirement for the two motif VI arginines; alanine, glutamine, and lysine substitutions at either position are lethal (14). Bidentate interaction of the proximal motif VI arginine with the γ-phosphate might enhance reaction chemistry by stabilizing the pentacoordinate phosphorane transition state. Substitution of lysine for the distal arginine of NPH-I (predicted from the NS3 structure to contact the α-phosphate) resulted in a fourfold increase in the Km for ATP; substitution of alanine for the corresponding arginine of NPH-II resulted in a similar increase in the Km for ATP (9). These data support the idea that motif VI contacts the NTP substrate. Entirely different mutational effects on ATPase activity were noted for the two analogous motif VI arginines of eIF4A. Mutants with lysine substituted for either arginine were active in ATP hydrolysis (with Vmax values 71 to 73% of the wild-type level and no significant effect on Km) but defective for RNA helicase function (22).

Conclusions.

We have identified by alanine scanning 9 amino acids in motifs I, II, III, and VI of vaccinia virus NPH-I that are essential for ATP hydrolysis. Structure-activity relationships were established for each position by performing conservative amino acid substitutions. Comparison of our findings with mutational studies of other DExH box and DEAD box proteins underscores similarities as well as numerous disparities. We conclude that the functions of the conserved amino acids of the NTPase motifs are context dependent and must therefore be established empirically for any given member of the DExH and DEAD families.

REFERENCES

- 1.Broyles S S, Moss B. Identification of the vaccinia virus gene encoding nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I, a DNA-dependent ATPase. J Virol. 1987;61:1738–1742. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1738-1742.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cho H-S, Ha N-C, Kang L-W, Chung K M, Back S H, Jang S K, Oh B-H. Crystal structure of RNA helicase from genotype 1b hepatitis C virus: a feasible mechanism of unwinding duplex RNA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15045–15052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christen L M, Sanders M, Wiler C, Niles E G. Vaccinia virus nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I is an essential viral early gene transcription termination factor. Virology. 1998;245:360–371. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deng L, Shuman S. An ATPase component of the transcription elongation complex is required for factor-dependent transcription termination by vaccinia RNA polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29386–29392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.29386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng L, Shuman S. Vaccinia NPH-I, a DExH-box ATPase, is the energy coupling factor for mRNA transcription termination. Genes Dev. 1998;12:538–546. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George J W, Brosh R M, Matson S W. A dominant negative allele of the Escherichia coli uvrD gene encoding DNA helicase II. J Mol Biol. 1994;235:424–435. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorbalenya A E, Koonin E V. Helicases: amino acid sequence comparisons and structure-function relationships. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1993;3:419–429. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gross C H, Shuman S. Mutational analysis of vaccinia virus nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase II, a DExH box RNA helicase. J Virol. 1995;69:4727–4736. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.8.4727-4736.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross C H, Shuman S. The QRxGRxGRxxxG motif of the vaccinia virus DExH box RNA helicase NPH-II is required for ATP hydrolysis and RNA unwinding but not for RNA binding. J Virol. 1996;70:1706–1713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1706-1713.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross C H, Shuman S. Vaccinia virus RNA helicase: nucleic acid specificity in duplex unwinding. J Virol. 1996;70:2615–2619. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2615-2619.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gross C H, Shuman S. The nucleoside triphosphatase and helicase activities of vaccinia virus NPH-II are essential for virus replication. J Virol. 1998;72:4729–4736. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4729-4736.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heilek G M, Peterson M G. A point mutation abolishes the helicase but not the nucleoside triphosphatase activity of hepatitis C virus NS3 protein. J Virol. 1997;71:6264–6266. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.6264-6266.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henikoff S. Transcriptional activator components and poxvirus DNA-dependent ATPases comprise a single family. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18:291–292. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90037-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hotz H R, Schwer B. Mutational analysis of the yeast DEAH-box splicing factor Prp16. Genetics. 1998;149:807–815. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.2.807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D W, Kim J, Gwack Y, Han J H, Choe J. Mutational analysis of the hepatitis C virus RNA helicase. J Virol. 1997;71:9400–9409. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9400-9409.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J L, Morgenstern K A, Griffith J P, Dwyer M D, Thomson J A, Murcko M A, Lim C, Caron P R. Hepatitis C virus NS3 RNA helicase domain with a bound oligonucleotide: the crystal structure provides insights into the mode of unwinding. Structure. 1998;6:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korolev S, Hsieh J, Gauss G H, Lohman T M, Waksman G. Major domain swiveling revealed by crystal structure of complexes of E. coli Rep helicase bound to single-stranded DNA and ADP. Cell. 1997;90:635–647. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins, A., and S. Shuman. Unpublished data.

- 19.Pai E F, Krengel U, Petsko G A, Goody R S, Kabsch W, Wittinghofer A. Refined crystal structure of the triphosphate conformation of H-ras p21 at 1.35 Å resolution: implications for the mechanism of GTP hydrolysis. EMBO J. 1990;9:2351–2359. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paoletti E, Moss B. Two nucleic acid-dependent nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolases from vaccinia virus. Nucleotide substrate and polynucleotide cofactor specificities. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:3281–3286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paoletti E, Rosemond-Hornbeak H, Moss B. Two nucleic acid-dependent nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolases from vaccinia virus: purification and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:3273–3280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pause A, Méthot N, Sonenberg N. The HRIGRXXR region of the DEAD box RNA helicase eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A is required for RNA binding and ATP hydrolysis. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:6789–6798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pause A, Sonenberg N. Mutational analysis of a DEAD box RNA helicase: the mammalian translation initiation factor eIF-4A. EMBO J. 1992;11:2643–2654. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pazin M J, Kadonaga J T. SWI2/SNF2 and related proteins: ATP-driven motors that disrupt protein-DNA interactions. Cell. 1997;88:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81918-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez J F, Kahn J S, Esteban M. Molecular cloning, encoding sequence, and expression of vaccinia nucleic acid-dependent nucleoside triphosphatase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9566–9570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shuman S. Vaccinia virus RNA helicase: an essential enzyme related to the DE-H family of RNA-dependent NTPases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10935–10939. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shuman S. Vaccinia virus RNA helicase: directionality and substrate specificity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11798–11802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Story R M, Steitz T A. Structure of the recA protein-ADP complex. Nature. 1992;355:374–376. doi: 10.1038/355374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramanya H S, Bird L E, Brannigan J A, Wigley D B. Crystal structure of a DExx box DNA helicase. Nature. 1996;384:379–383. doi: 10.1038/384379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sung P, Higgins D, Prakash L, Prakash S. Mutation of lysine-48 to arginine in the yeast RAD3 protein abolishes its ATPase and DNA helicase activities but not the ability to bind ATP. EMBO J. 1988;7:3263–3269. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yao N, Hesson T, Cable M, Hong Z, Kwong A D, Le H V, Weber P C. Structure of the hepatitis C virus RNA helicase domain. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nsb0697-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zavitz K H, Marians K J. ATPase-deficient mutants of the Escherichia coli DNA replication protein PriA are capable of catalyzing the assembly of active primosomes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6933–6940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]