Abstract

Although the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) primarily involves the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, neurological manifestations, including movement disorders such as myoclonus and cerebellar ataxia, have also been reported. However, the occurrence of post-SARS-CoV-2 chorea is rare. Herein, we describe a 91-year-old female with a past medical history of hypothyroidism who developed chorea after two weeks of contracting a mild coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

Keywords: post-acute sequelae of sars-cov-2, sars-cov-2 infection, covid-19, choreiform movement disorder, chorea

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel respiratory virus that emerged in 2019 and caused a global pandemic called COVID-19. While this virus primarily affects the cardio-respiratory system, post-infectious neurological complications are not uncommon [1,2]. Though neurocognitive impairment and olfactory neuropathy are among the most common neurologic complications, meningitis, encephalitis, Guillan-Barre syndrome, strokes, and movement disorders, including myoclonus, ataxia, and action tremor, have also been reported [2,3]. However, the occurrence of post-SARS-CoV-2 chorea is rare, and to our knowledge, there have been less than 20 cases reported in the literature.

This article was previously presented as a meeting abstract at the XXVIII World Congress on Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders on May 15, 2023.

Case presentation

A 91-year-old female was referred to our clinic for evaluation of abnormal involuntary movements. Six months before the evaluation, she had a bout of mild flu-like symptoms (cough, rhinorrhea, fatigue) and was diagnosed with COVID-19 after testing positive for coronavirus by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) nasopharyngeal swab. She did not require admission from the infection and recovered in home isolation without medical intervention. She had also received two previous COVID-19 (MODERNA) vaccines about 10 months prior to her presentation.

Two weeks after the flu-like symptoms, she developed excessive involuntary movements of the tongue, jaw, and face. Over the ensuing months, she developed excessive movements involving the arms, legs, and torso. She had no family history of a movement disorder, no personal history of anti-dopaminergic medications, tobacco, or alcohol, and her past medical history was significant only for hypothyroidism. She lived alone and was able to perform her activities of daily living before the onset of these involuntary movements. Systemic and neurological examinations were normal, except for choreiform movements in the face and bilateral upper and lower extremities, albeit her left side was more predominantly affected, as shown in Video 1.

Video 1. Generalized chorea albeit left hemibody predominant.

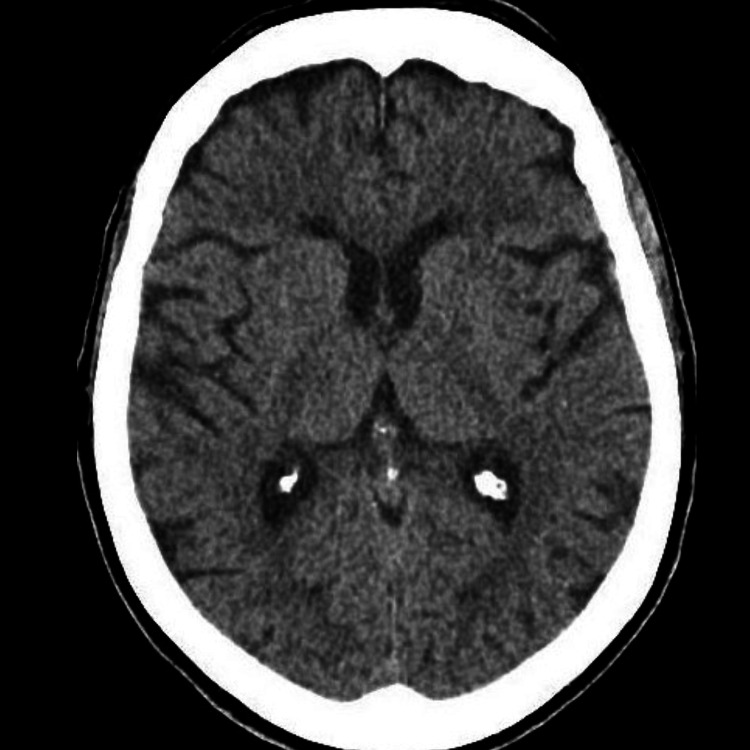

Extensive diagnostic testing for chorea including complete blood count with peripheral smear, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid studies, serum paraneoplastic panels, and neuroimaging with computed tomography of the head (Figure 1) and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain was all unremarkable. Genetic testing for Huntington’s disease was not performed at the patient’s request. She was started on tetrabenazine 6.25 mg daily, six months after the onset of choreiform movements, and experienced more than 90% improvement in both facial and appendicular symptoms at one month and one-year follow-up (Video 2)

Figure 1. Computed tomography (CT) of the head with normal caudate and thalamus.

Video 2. Minimal chorea on follow-up.

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 relies on the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor for entry into the cells and affects the central nervous system likely through transmission via the olfactory nerve and or dissemination from the respiratory tract via the vagus nerve to the brainstem (nucleus solitarius and nucleus ambiguus in the medulla oblongata and midbrain) [2,4]. Concerning COVID-19-associated movement disorders, two mechanisms have been postulated: a) virus-induced gliosis and cellular vacuolation and b) striatal ACE-2 receptor downregulation, causing an imbalance of norepinephrine and dopamine [5].

Chorea is a hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by involuntary, sudden, brief, and irregular movements. Sydenham’s chorea is the most common para/postinfectious entity due to autoimmunity against the basal ganglia post-streptococcal infection [1]. On the other hand, the pathogenesis of COVID-19-associated chorea is poorly understood. It is thought to be secondary to autoimmune antibodies against brain structures such as basal ganglia, on the lines of Sydenham’s chorea. Some authors have also suggested that localized hyperviscosity and focal endotheliopathy from the spike protein in the basal ganglia and thalamus contribute to neuronal dysfunction and the generation of chorea [4,6,7].

We have summarized the cases published so far with para/post-COVID-19 chorea in Table 1. The age of onset varied from eight years to 91 years, with our patient being the oldest to have developed post-COVID chorea at 91 years. In most cases, chorea developed following the onset of COVID-19 symptoms with the longest interval between the onset of chorea and COVID-19 symptoms being three months. However, there have been situations when chorea has developed along with or even preceding COVID-19 symptoms.

Table 1. Cases of COVID-19-associated chorea.

M: Male

F: Female

RT-PCR: Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid

PCR: Polymerase chain reaction

CRP: C-reactive protein

ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

SWI: Susceptibility-weighted imaging

SPECT: Single-photon emission computed tomography

| Author | Age/Gender | Symptom onset | Clinical features | Lab results | Imaging | Treatment | Outcome |

| DeVette et al. [8] | 8 y.o. F | Two weeks after parents tested positive for COVID-19 | Hemichorea of right arm and leg, behavioral changes, and gait instability | RT-PCR positive for COVID-19, elevated anti-streptolysin-O, anti-DNase-B | Normal | Valproate | Continued to have chorea at one-month follow-up |

| Ray et al. [9] | 9 y.o., Not available 14 y.o., Not available | Not available | Not available | CSF studies not performed; SARS-CoV-2 IgG positive | Not available | No immunomodulation | Not available |

| Yuksel et al. [10] | 14 y.o. F | Three days after being diagnosed with COVID-19 | Bilateral shoulder shrugging, choreiform movements in all four limbs, and bilateral milkmaid's grip. History of Sydenham’s chorea three yrs ago (resolved with haloperidol) | Iron deficiency anemia | Normal | Carbamazepine | Chorea improved by the seventh day of admission |

| Byrnes et al. [11] | 36 y.o. M | Four days prior to COVID-19 diagnosis | Homeless male with generalized chorea and mild encephalopathy | Decreased lymphocytes, SARS-CoV2 CSF PCR negative | Bilateral medial putamen and left cerebellar hyperintensities on T2-weighted imaging | IVIG, methylprednisolone | Chorea improved by day 15 with complete cessation by day 22 |

| Hassan et al. [4] | 58 y.o. M | Not known | Chorea in hands and feet | SARS-CoV-2 positivity in CSF, Leukocytosis, elevated CRP, D-dimer, and ferritin | Mild periventricular ischemic changes | Methylprednisolone, amantadine, risperidone | Improved by day 14 |

| Ghosh et al. [12] | 60 y.o. M | 36 hours after onset of fever, cough, throat ache, malaise | Right-sided hemichorea-hemiballismus | Capillary glucose 540 mg/dL, ketonuria, metabolic acidosis, elevated ESR, CRP | Left striatal hyperintensity on T1-weighted imaging | Insulin for diabetic ketoacidosis | Complete resolution at six-month follow-up |

| Ramusino et al. [13] | 62 y.o. M | Two days prior to COVID-19 diagnosis | Generalized chorea in all four limbs, head, and trunk. Mild encephalopathy | CSF PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2 | Hypointense signal in the dorsolateral portion of putamen bilaterally on SWI sequence | Tetrabenazine, haloperidol | Resolution of chorea after two months from onset |

| Ashrafi et al. [3] | 62 y.o. F | Two weeks after COVID-19 diagnosis | Choreiform movements in all limbs, predominantly on the right side | Elevated ESR, CRP | Normal | Tetrabenazine | Improvement seen; duration not available |

| Ashrafi et al. [3] | 67 y.o. F | Three months after COVID-19 diagnosis | Random involuntary choreiform movements in her face and all four limbs, with right arm dominancy | Normal | Damaged bilateral basal ganglia | Tetrabenazine | Improvement seen; duration not available |

| Revert Barbera et al. [14] | 69 y.o. F | Before | Mild right hemiparesis, generalized choreiform movements, seizures, and diffuse encephalopathy | Elevated D-dimer | Bilateral capsuloganglionic and thalamic infarcts. Also, with venous thrombosis of the left lateral sinus, straight sinus, and vein of Galen | Anticoagulation with enoxaparin for sinus thrombosis | Fatal from a hemorrhagic transformation of the left thalamic infarct |

| Our patient | 91 y.o. F | 14 days after the onset of flu-like symptoms | Choreiform movements in the face and all four limbs with left-side dominance | Normal | Normal | Tetrabenazine | Chorea improved 90% at one-month follow-up |

| Salari et al. [1] | 13 y.o. M | Seven days after vaccination | Large amplitude choreiform movements on the right side | Normal | Multiple white matter lesions, one lesion enhancing with gadolinium | Intravenous methylprednisolone and tetrabenazine | Chorea improved at one-month follow-up |

| Salari et al. [1] | 18 y.o. M | Seven days after vaccination | Choreiform movements affecting the left, shoulder, and mildly in the left leg | Normal | Few nonspecific white matter lesions | Intravenous methylprednisolone and tetrabenazine | Persistent chorea at one-month follow-up |

| Matar et al. [6] | 88 y.o. M | 16 days after vaccination | Choreiform movements in the left arm, leg, and face | Normal | Chronic small vessel ischemic change | Intravenous methylprednisolone | Resolution within 24 hours of steroid initiation |

| Matar et al. [6] | 84 y.o. M | 40 days after vaccination | Choreiform movements of left upper and lower limbs | Normal | Chronic small vessel ischemic change | Intravenous methylprednisolone | Resolution after three days of steroid initiation |

| Ryu et al. [7] | 83 y.o. M | One day after vaccination | Choreiform movements affecting the right arm, and leg | Normal | Normal MRI, Brain SPECT with decreased perfusion in the left thalamus | Haloperidol | Resolution at two-week follow-up |

Choreiform movements can be generalized or prefer one side even with a paucity of a structural lesion. With regards to COVID-19 vaccination, movement disorders’ frequency of occurrence is low (0.00002-0.0002), and tremor was the most reported side effect [2]. Salari et al. described two cases of chorea as a side effect of COVID-19 vaccination [1]. Neuroimaging can be normal but can show changes predominantly in the striatum and cerebellum [11-13]. Therapeutic options can range from tetrabenazine (most common), antipsychotics such as risperidone, haloperidol, immunomodulation with steroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, and to less common valproate and carbamazepine. Most cases have shown improvement and/or resolution with time.

Conclusions

Even though chorea is rare, clinicians should be aware of it as a possible sequela of COVID-19 infection and in certain cases with vaccination. Our case also highlights that chorea post-COVID-19 is independent of the severity of COVID-19 infection.

Acknowledgments

Benjamin G. Grimm and Prashant A. Natteru contributed equally to the work and should be considered co-first authors.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Two cousins with acute hemichorea after BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) COVID-19 vaccine. Salari M, Etemadifar M. Mov Disord. 2022;37:1101–1103. doi: 10.1002/mds.28979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Relationship between COVID-19 and movement disorders: A narrative review. Schneider SA, Hennig A, Martino D. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:1243–1253. doi: 10.1111/ene.15217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chorea as a post-COVID-19 complication. Ashrafi F, Salari M, Hojjati Pour F. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2022;9:1144–1148. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chorea as a presentation of SARS-CoV-2 encephalitis: A clinical case report. Hassan M, Syed F, Ali L, Rajput HM, Faisal F, Shahzad W, Badshah M. J Mov Disord. 2021;14:245–247. doi: 10.14802/jmd.20098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chorea in the times of COVID- 19: Yet another culprit. Garg D, Gotur A. https://journals.lww.com/aomd/Fulltext/2022/05020/Chorea_in_the_times_of_COVID_19__Yet_another.8.aspx Ann Mov Disord. 2022;5:131–133. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acute hemichorea-hemiballismus following COVID-19 (AZD1222) vaccination. Matar E, Manser D, Spies JM, Worthington JM, Parratt KL. Mov Disord. 2021;36:2714–2715. doi: 10.1002/mds.28796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A case of hemichorea following administration of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Ryu DW, Lim EY, Cho AH. Neurol Sci. 2022;43:771–773. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05763-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acute rheumatic fever in a COVID-19-positive pediatric patient. DeVette CI, Ali CS, Hahn DW, DeLeon SD. Case Rep Pediatr. 2021;2021:6655330. doi: 10.1155/2021/6655330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection in hospitalised children and adolescents in the UK: A prospective national cohort study. Ray ST, Abdel-Mannan O, Sa M, et al. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2021;5:631–641. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.A sydenham chorea attack associated with COVID-19 infection. Yüksel MF, Yıldırım M, Bektaş Ö, et al. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2021;13:100222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2021.100222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.COVID-19 encephalopathy masquerading as substance withdrawal. Byrnes S, Bisen M, Syed B, et al. J Med Virol. 2020;92:2376–2378. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De novo movement disorders and COVID-19: Exploring the interface. Ghosh R, Biswas U, Roy D, Pandit A, Lahiri D, Ray BK, Benito-León J. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2021;8:669–680. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SARS-CoV-2 in a patient with acute chorea: Innocent bystander or unexpected actor? Cotta Ramusino M, Perini G, Corrao G, Farina L, Berzero G, Ceroni M, Costa A. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2021;8:950–953. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revert Barberà A, Estraguès GI, Beltrán MMB, et al. Bilateral chorea as a manifestation of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis associated with COVID-19. 2022;37:507–509. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2021.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]