Abstract

Rationale

Increasing survival of extremely preterm infants with a stable rate of severe intraventricular hemorrhage represents a growing health risk for neonates.

Objectives

To evaluate the role of early hemodynamic screening (HS) on the risk of death or severe intraventricular hemorrhage.

Methods

All eligible patients 22–26+6 weeks’ gestation born and/or admitted <24 hours postnatal age were included. As compared with standard neonatal care for control subjects (January 2010–December 2017), patients admitted in the second epoch (October 2018–April 2022) were exposed to HS using targeted neonatal echocardiography at 12–18 hours.

Measurements and Main Results

A primary composite outcome of death or severe intraventricular hemorrhage was decided a priori using a 10% reduction in baseline rate to calculate sample size. A total of 423 control subjects and 191 screening patients were recruited with a mean gestation and birth weight of 24.7 ± 1.5 weeks and 699 ± 191 g, respectively. Infants born at 22–23 weeks represented 41% (n = 78) of the HS epoch versus 32% (n = 137) of the control subjects (P = 0.004). An increase in perinatal optimization (e.g., antepartum steroids) but with a decline in maternal health (e.g., increased obesity) was seen in the HS versus control epoch. A reduction in the primary outcome and each of severe intraventricular hemorrhage, death, death in the first postnatal week, necrotizing enterocolitis, and severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia was seen in the screening era. After adjustment for perinatal confounders and time, screening was independently associated with survival free of severe intraventricular hemorrhage (OR 2.09, 95% CI [1.19, 3.66]).

Conclusions

Early HS and physiology-guided care may be an avenue to further improve neonatal outcomes; further evaluation is warranted.

Keywords: targeted neonatal echocardiography, extremely preterm infant, intraventricular hemorrhage, necrotizing enterocolitis, bronchopulmonary dysplasia

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Targeted neonatal echocardiography is increasingly available in U.S. centers to provide physiologic delineation; theoretically, targeted neonatal echocardiography may be used to mitigate altered systemic blood flow using a physiology-based, as opposed to symptom-based, approach, although there is a paucity of data.

What This Study Adds to the Field

A novel approach to hemodynamic screening using neonatologist-performed echocardiography enables enhanced diagnostic precision and clinical phenotype profiling. This approach was associated with a reduction in the composite of death or severe intraventricular hemorrhage.

Over the past 20 years, survival of extremely preterm neonates has improved, particularly at the limits of viability (1). Although the rates of severe (grade III/IV) intraventricular hemorrhage (sIVH) have gradually improved, the prevalence remains high, particularly at younger gestations (1, 2). Several preventative interventions have been evaluated, of which receipt of antepartum steroids is most protective (2) and other factors, such as delivery room intubation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation, demonstrate a greater risk at older gestational age (GA) (2). The effectiveness of IVH bundles is controversial and has been studied in few infants at 22–23 weeks gestation, who represent the highest-risk population (3, 4). Between 50% and 75% of infants surviving with sIVH develop long-term neurological sequelae, including intellectual disability, hydrocephalus, and/or cerebral palsy (5). Treatment options are limited to symptomatic relief of hydrocephalus with serial lumbar punctures and/or neurosurgical intervention. Therefore, prevention of sIVH is essential to enhance outcomes.

The pathophysiology of sIVH is related to developmental vulnerability of the immature germinal matrix, which thins after 24 weeks and almost disappears by late prematurity (6). Fluctuations in cerebral blood flow are implicated in the pathogenesis of IVH. In 117 preterm infants, Kluckow and Evans identified a high prevalence of low superior vena cava flow among neonates who experienced IVH (7). Similarly, Noori and Seri demonstrated that neonates who experienced IVH had an initial period of low cardiac output, followed by increased flow with higher middle cerebral artery velocity before the onset of hemorrhage. In comparison, neonates without IVH experienced a more gradual rise in cardiac output and middle cerebral artery flow (8).

Although postnatal transition is characterized by changes in cardiac loading conditions and blood flow, the traditional approach to cardiovascular support focuses on arbitrary blood pressure thresholds with an exclusive emphasis on dopamine infusions to correct a presumed low systemic vascular resistance state (9). Preliminary data (10), however, suggest that the contributors to transitional cardiovascular insufficiency are complex and may include cardiac dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, and shunts, which may be clinically underappreciated and may require alternative treatment approaches. When performed as part of a comprehensive hemodynamic evaluation, targeted neonatal echocardiography (TnECHO) is a valuable tool to guide characterization of physiology and implementation of an individualized treatment plan. We hypothesized that the introduction of a standardized hemodynamic assessment and physiology-guided therapy in the first 24 postnatal hours would reduce the burden of death and/or sIVH among extremely preterm neonates.

Methods

A cohort of neonates born at <27 weeks, who were either inborn or admitted within 24 hours postnatal age to a single quaternary neonatal ICU (NICU; University of Iowa), was evaluated. Institutional review board approval was obtained with waiver of consent. Patients were identified from a clinically maintained database, and the patients’ electronic medical records were used to abstract data.

Criteria for Eligibility

All neonates during the study period were eligible and included unless they satisfied any of the exclusion criteria. Patients with major anomalies, with congenital heart disease (other than patent ductus arteriosus [PDA], small ventricular septal defect [<1 mm], or atrial communication) present, or when resuscitation was incomplete or not provided were excluded. Patients were recruited in two epochs: hemodynamic screening (HS; October 2018–April 2022) or historical control subjects (HC; January 2010–December 2017). Patients from January 2018 through September 2018 were not analyzed to account for the learning curve of implementing a new approach.

Clinical Data Collection

Factors associated with adverse neonatal outcomes were collected. This includes maternal and pregnancy variables (e.g., maternal illnesses, fertility treatment, obesity, chorioamnionitis, preterm prolonged rupture of membranes [PPROM], maternal smoking, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] use, substance use disorders, and age). Delivery mode, fetal presentation, antepartum steroids, magnesium sulfate, antibiotics, tocolysis, and delayed cord clamping (DCC) were abstracted. Neonatal factors that may be associated with IVH, including GA and birth weight, platelet count, hemoglobin, details of carbon dioxide (CO2) fluctuation in the first 24 hours defined by the difference in the lowest versus highest recorded value, and presence of a morphine infusion, were collected. The Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology with Perinatal Extension II score (11) was used to adjudicate illness severity in the first 24 postnatal hours, and characteristics of cardiovascular therapy (e.g., inhaled nitric oxide [iNO], vasopressors, inotropes, vasoactive score [12]) were characterized, as was the adequacy of oxygenation using oxygenation index or respiratory severity score if PaO2 was not available.

Characteristics of HS

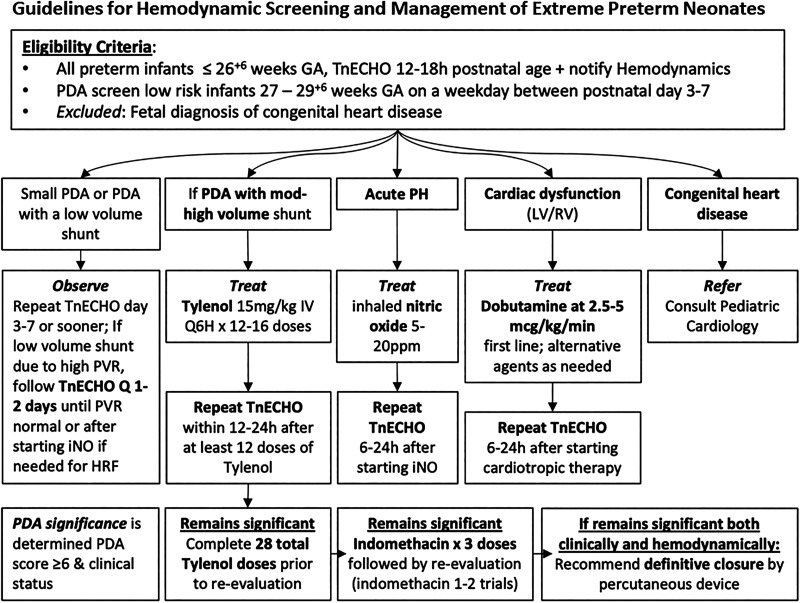

In addition to standard neonatal care (see below), during the HS epoch, all neonates underwent comprehensive TnECHO at 12–18 hours’ postnatal age followed by physiology-guided therapy. TnECHO evaluations were performed by five neonatology hemodynamic specialists (R.E.G., A.R.B., A.H.S., D.R.R., P.J.M.) with advanced hemodynamics training and were completed within 20 minutes (13). Each TnECHO consisted of 80–110 clips and included a comprehensive appraisal of systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics, objective measurement of biventricular cardiac function, and characterization of shunts (see Appendix E1 in the online supplement). Essential images to screen for major congenital heart disease and central line position were included. Studies were conducted using a GE Vivid E90 with a 12-mHz multisector probe (GE Medical) with warmed, sterile gel and archived. Acute pulmonary hypertension (aPH) and left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) dysfunction were defined according to published definitions (Appendix E2). A hemodynamically significant PDA (hsPDA) was diagnosed on the basis of an Iowa PDA score ⩾6 (14). Management was guided by the specific physiology (Figure 1) as follows: 1) aPH was treated with iNO at 5–20 ppm (clinician discretion), which was weaned over 4–12 hours in responders. Finally, patients who received iNO were followed closely with echocardiography to identify transition to PDA physiology. 2) LV/RV dysfunction was treated with intravenous dobutamine at a starting dose of 2.5–5 μg/kg/min, and if the patient was a nonresponder to a maximum of 10 μg/kg/min, the patient was transitioned to low-dose (0.03–0.05 mg/kg/min) epinephrine. 3) hsPDA was treated with intravenous acetaminophen 15 mg/kg every 6 hours for 3–7 days according to the response on Day 3 by repeat TnECHO. Follow-up TnECHO was performed serially, depending on the clinical condition. When TnECHO was clinically requested before the screening window, a repeat evaluation was performed between 12 and 18 hours to reappraise physiology.

Figure 1.

Management algorithm after screening targeted neonatal echocardiogram. Treatment is based on the underlying pathophysiology identified on the screening evaluation. GA = gestational age; HRF = hypoxemic respiratory failure; iNO = inhaled nitric oxide; IV = intravenous; LV = left ventricular; PDA = patent ductus arteriosus; PH = pulmonary hypertension; ppm = parts per million; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; Q6H = every 6 hours; RV = right ventricular; TnECHO = targeted neonatal echocardiography.

Standard Neonatal Care

The approach to care of extremely preterm infants includes active obstetric management with antepartum steroids beginning at 21+5 weeks, cesarean section for fetal indications starting at 23+0 weeks, magnesium sulfate for IVH prophylaxis, standard latency antibiotics for PPROM and routine DCC for 30 seconds (introduced in 2012). In both epochs, the approach to neonatal respiratory care and IVH prevention includes the use of first intention high-frequency jet ventilation, surfactant prophylaxis at ⩽24 weeks, universal caffeine, and midline positioning for the first 14 days (15). Enteral feeds, primarily breast or donor milk, are increased slowly in the first postnatal week according to a standardized guideline. Early extubation is not a routine practice, because patients must reach a postnatal weight of 900 g to allow the placement of a neurally adjusted ventilatory assist catheter to facilitate neurally adjusted ventilatory assist–mediated noninvasive ventilation. Prophylactic indomethacin was not used in either epoch. Intravenous dobutamine was also used clinically for low systolic blood pressure below the third centile, based on enhanced optimization of systemic blood flow compared with dopamine (16). The response to dobutamine was monitored by following urinary output, plasma lactate, and arterial pH and performing serial echocardiography (timing adjudicated by severity of dysfunction) to adjudicate response to intervention. Intravenous hydrocortisone was administered for presumed adrenal insufficiency by some clinicians if hypotension was identified (17) at a dose of 1 mg/kg (load) followed by a weaning course over 4 days. Routine head ultrasound (US) was performed on Postnatal Day 7 or earlier if clinically indicated in both epochs; however, in the HS epoch, a head US was also routinely performed by hemodynamic specialists as part of the first TnECHO evaluation. For the HC epoch, it was standard to obtain echocardiography at the end of the first postnatal week; however, several patients (n = 9) had earlier (transitional period) evaluations based on clinical concern, and for some patients, the first echocardiogram was only after Day 10. In the historical epoch, the approach to cardiovascular care was focused on correction of low blood pressure with dopamine and/or hydrocortisone. The approach to hsPDA was aggressive medical therapy beginning in Week 2 (up to three courses of indomethacin 0.2 mg/kg, then 0.25 mg/kg × 2 at every 12-hour intervals) followed by surgical ligation.

Outcome

The primary outcome was a composite of death before NICU discharge and sIVH defined using Papile’s criteria (18) as grade 3 or higher. Secondary outcomes included death and sIVH as individual outcomes, survival free of major morbidity (e.g., necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (19), grade 3 bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) using Jensen (20) criteria, sIVH) pulmonary hemorrhage, pneumothorax, PDA therapy, intestinal complications (e.g., spontaneous intestinal perforation) (19), and retinopathy of prematurity treatment. In addition, the approach to cardiovascular care, including early cardiovascular support and PDA management/interventional closure, was compared between the two epochs.

Statistics

On the basis of historical rates of death or sIVH and presuming unequal group sizes with approximately 425 historical patients available, a sample size of at least 169 patients was needed in the modern epoch to detect a 10% difference—25% and 15% deaths in the HC and HS epochs, respectively—in the primary outcome (power, 0.8; type I error, 0.05). Data were evaluated for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Univariate analysis was performed. Normally distributed and nonnormally distributed data were tested using the mean, SD, and Student’s t test and the median with interquartile range and Wilcoxon signed-rank test, respectively. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The multivariable logistic regression framework was used to assess the effects of time (continuous), epoch, and other independent variables on survival without sIVH. Three similar models with varying parametric constraints based on birth year and epoch were considered. The first model included birth year but not epoch to assess an overall sample trend. The second model included epoch but not birth year to provide a simple pre–post comparison. The third model included an interaction effect between epoch and birth year to test for a slope difference while requiring the same intercept for both epochs to maintain predictive continuity at the intervention date. Additional covariates (GA, multiple births, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, bicarbonate receipt in the first 24 hours, DCC, breech vaginal delivery, sex, SSRI use, PPROM, obesity, drug use, magnesium exposure, inborn, and treatment with dopamine) were considered for inclusion using an all-subsets modeling algorithm that fixes the epoch–birth year interaction in the predictor set. These models were fit on the basis of all possible combinations of the candidate covariates and compared using the Akaike information criterion (AIC). This measure balances goodness of fit and parsimony, and a lower AIC indicates a more appropriate model specification. Covariates in the model predictor set with the minimum AIC were then included as predictors in all three models mentioned above. Odds ratio (OR) point and interval estimates were calculated for all covariates along with the test P values. SPSS version 29 (IBM Corp.) was used.

Results

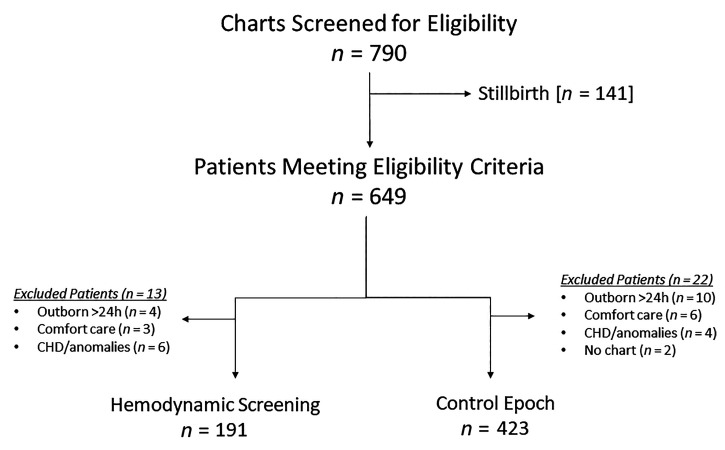

A total of 614 patients (HC, n = 423; HS, n = 191) were recruited from a total eligible population of 790 charts screened. Figure 2 demonstrates the reasons for exclusion. The overall mean GA and birth weight were 24.7 ± 1.5 weeks and 699 ± 191 g, respectively, which was not different between the epochs; however, infants born at 22–23 weeks represented 41% (n = 78) of the HS epoch versus 32% (n = 137) of the HCs (P = 0.004). The median and interquartile range age at screening echo in the HS epoch was 16.8 hours (12.8, 18.8), and all patients in the HS era were screened. Findings based on TnECHO screening included the following: hsPDA (n = 71; 37%); aPH (n = 11; 6%); isolated RV (n = 2; 1%), LV (n = 10; 5%), or biventricular (n = 9; 5%) dysfunction; and findings in keeping with hypovolemia/vasodilator shock (n = 2; 1%), many of which would represent absolute contraindications to prophylactic indomethacin. In addition, screening TnECHO identified one patient with a presymptomatic aortic coarctation and two with moderate or large ventricular septal defects (n = 3 of 194; 2%). These patients with anatomic disease were excluded (Figure 2). In the HS epoch, two patients had moderate or large pericardial effusions that resolved by pulling back the umbilical venous catheter. There was a trend toward a greater frequency of male births in the HS epoch without differences in inborn birth, 5-minute Apgar score, and delivery room intubation (Table 1). In the HC epoch, only 9 patients (2%) had their first echo in the transitional period, and 39 (9%) were not evaluated until after the first 10 postnatal days. A total of 35 (18%) of 191 neonates in the HS epoch had earlier (<12 h) TnECHO evaluation because of clinician concerns of hemodynamic instability (n = 27; 14%) and/or hypoxemic respiratory failure (n = 8; 4%).

Figure 2.

Patient flow diagram. Three of the patients with congenital heart disease (CHD) underwent screening but were excluded post hoc because of findings of aortic coarctation and two large ventricular septal defects. The remaining three patients with CHD were known antenatally and were therefore not screened.

Table 1.

Neonatal Demographics, Pregnancy Characteristics, and Perinatal Factors for Severe Intraventricular Hemorrhage of Hemodynamic Screening versus Historical Control Subjects

| Hemodynamic Screening (n = 191) | Historical Control Subjects (n = 423) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age, wk | 24.6 ± 1.5 | 24.8 ± 2.1 | 0.1 |

| Number of 22–23-wk neonates | 78 (41) | 137 (32) | 0.04 |

| Birth weight, g | 686 ± 185 | 704 ± 193 | 0.32 |

| Female | 85 (45) | 222 (53) | 0.07 |

| Inborn | 165 (86) | 343 (82) | 0.11 |

| 5-min Apgar score | 7 [6, 7] | 7 [6, 8] | 0.78 |

| Intubation in delivery room | 178 (93) | 376 (89) | 0.1 |

| CPR in the delivery room | 4 (2) | 30 (7) | 0.02 |

| Maternal factors | |||

| Antepartum steroids | |||

| None | 14 (7) | 58/421 (14) | 0.03 |

| Partial | 41 (22) | 102/421 (24) | |

| Complete | 136 (71) | 261/421 (62) | |

| Maternal magnesium sulfate | 156/179 (87) | 165/336 (49) | <0.001 |

| Delayed cord clamping | 101/177 (57) | 61/353 (17) | <0.001 |

| Maternal antibiotics | |||

| None | 30/179 (17) | 116/335 (35) | <0.001 |

| Partial | 46/179 (26) | 70/355 (21) | |

| Complete | 103/179 (58) | 149/355 (45) | |

| Pregnancy/delivery factors | |||

| Maternal age, yr | 28.9 ± 6 | 27.4 ± 6 | 0.004 |

| Multiple birth | 57 (30) | 109 (26) | 0.91 |

| Fertility treatment | 11/173 (5) | 34/420 (8) | 0.47 |

| Antepartum NSAID exposure | 13/171 (8) | 4/416 (1) | <0.001 |

| Obesity | 70/177 (40) | 54/416 (13) | <0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes | 11/184 (6) | 25/420 (6) | 0.99 |

| Hypertension of pregnancy | 20/188 (11) | 47/421 (11) | 0.51 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 21/186 (11) | 57/422 (14) | 0.45 |

| Prolonged rupture of membranes | 70 (37) | 122/418 (29) | 0.07 |

| Maternal smoking | 32/188 (17) | 92/418 (22) | 0.16 |

| Maternal SSRI use | 19/179 (11) | 12/415 (3) | <0.001 |

| Maternal drug use | |||

| None | 145/190 (85) | 377/418 (90) | <0.001 |

| Cannabis | 31/190 (16) | 25/418 (6) | |

| Methamphetamine | 1/190 (1) | 3/418 (1) | |

| Opiates | 2/190 (1) | 4/418 (1) | |

| Alcohol | 7/190 (4) | 3/418 (1) | |

| Multiple | 4/190 (2) | 6/418 (1) | |

| Induction of labor | 7/182 (4) | 12/355 (3) | 0.78 |

| Delivery mode | |||

| Vaginal | 104 (47) | 189/421 (44) | 0.17 |

| Primary cesarean section | 87 (49) | 202/421 (48) | |

| Mixed (multiple birth) | 0 (4) | 30/421 (7) | |

| Breech vaginal delivery | 28 (15) | 33/304 (11) | 0.21 |

| Neonatal IVH risk factors 0–24 h | |||

| Platelets <100 | 7/185 (4) | 21/385 (6) | 0.39 |

| Morphine infusion | 21 (11) | 32/395 (8) | 0.25 |

| Change in CO2 in the first 24 h (mm Hg) | 62.5 ± 16 | 60.5 ± 16 | 0.18 |

| Lowest CO2 in the first 24 h, mm Hg | 35.7 ± 6 | 36.6 ± 11 | 0.43 |

| Mean hemoglobin, g/dl | 14.1 ± 1.8 | 13.8 ± 2 | 0.09 |

| Lowest hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.6 ± 2.2 | 12.4 ± 2.4 | 0.26 |

| Echocardiography evaluation | 191 (100) | 378/420 (90) | <0.001 |

| Postnatal day at first echocardiography | 0 [0, 0] | 6 [5, 7] | <0.001 |

| Peak illness severity 0–24 h | |||

| Mean respiratory severity score, mmol/L | 2.0 [1.7, 2.5] | 2.1 [1.6, 2.8] | 0.36 |

| Mean oxygenation index*, mmol/L | 3.9 [3, 5.2] | 4.1 [2.9, 5.9] | 0.22 |

| Sodium bicarbonate bolus | 8 (4) | 119 (29) | <0.001 |

| SNAPPE-II score, mmol/L | 21 [14, 30] | 24 [14, 36] | <0.001 |

| Highest lactate*, mmol/L | 4.5 [3, 6.9] | 5.1 [2.9, 8.8] | 0.12 |

| Approach to cardiovascular support | |||

| Inhaled nitric oxide in the first week | 9/182 (5) | 65/416 (16) | <0.001 |

| Hypotension in the first week† | 139 (73) | 346 (82) | 0.013 |

| Fluid alone | 31 (24) | 195/345 (55) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressor approach‡ | 3 (2) | 104 (30) | |

| Inotrope approach§ | 61 (47) | 13 (4) | |

| Hydrocortisone alone | 21 (16) | 27 (8) | |

| ⩾2 vasoactive infusions | 15 (12) | 6 (2) | |

| Maximum vasopressor-inotrope score | 5 [5, 12.5] | 10 [6, 14] | 0.005 |

| Hydrocortisone exposure first week | 99/190 (52) | 288 (70) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: CPR = cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IVH = intraventricular hemorrhage; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SNAPPE-II = score for neonatal acute physiology with perinatal extension-II; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Data are expressed as mean ± SD, median [interquartile range], or frequency (percent).

Oxygenation index; arterial lactate available in n = 158 of 191 hemodynamic screening and n = 363 of 423 historical control subjects.

Mean arterial pressure < gestational age ⩾3 h consecutively.

Vasopressor approach is dopamine, norepinephrine, or vasopressin use.

Inotrope approach is dobutamine or epinephrine use.

Perinatal Factors

The rates of complete antepartum steroids (P = 0.03), latency antibiotics (P < 0.001), magnesium sulfate (P < 0.001), and DCC (P < 0.001) were higher in the HS epoch (Table 1). In contrast, there was an increase in maternal factors associated with higher risk of neonatal complications; specifically, older maternal age (P = 0.004) and evidence of declining maternal health, such as increased rate of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug exposure (P < 0.001), obesity (P < 0.001), substance use disorders (P < 0.001), and SSRI exposure (P < 0.001) (Table 1). There was a stable incidence of cesarean section, fertility treatment, and other common morbidities of pregnancy, such as diabetes, hypertension, and chorioamnionitis between epochs. Neonatal risk factors, including thrombocytopenia, the use of morphine infusions, and magnitude of CO2 fluctuations, were similar between the two epochs.

Approach to Treatment of Acute Hemodynamic Instability

In the HS era, the worst Score for Neonatal Acute Physiology with Perinatal Extension II peak scores were lower, as were the uses of bolus sodium bicarbonate and iNO. The approach to hemodynamic support was characterized by predominant fluid or vasopressor support (e.g., dopamine) in the HC epoch, whereas the predominant approach in the HS era was based on heart function support (e.g., dobutamine). In addition, cumulative maximum doses of vasopressors or inotropes were lower in the HS epoch (Table 1). Approximately one-third (n = 71; 37%) of HS patients received medical treatment for hsPDA beginning within the first 24 postnatal hours, and a further 39 patients (20%) later required therapy at a median of 3.5 (2, 6) days.

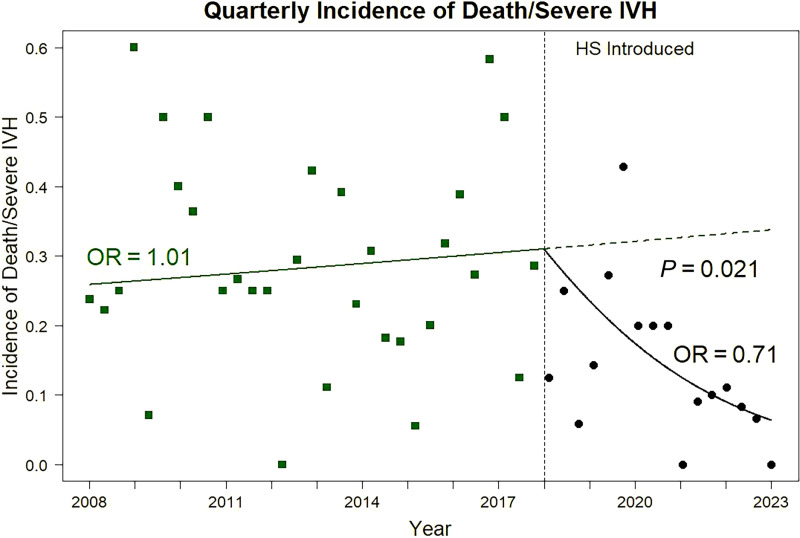

Outcomes

The composite of death/sIVH was reduced by approximately half in the HS era (P < 0.001) (Table 2), and individual components of the primary outcome were also lower. As shown in Figure 3, the odds of the composite of death/sIVH increased by 1% per year in the HC epoch and decreased by 41% per year in the HS epoch, reflecting a new, more rapid increase in survival free of sIVH after HS was introduced (P < 0.05; analysis of covariance). Survival free of severe morbidity increased (P < 0.001), and the incidence of ventilator dependence at 36 weeks (P = 0.02) was lower in the HS era. The incidence of NEC, which was already low at 6% in HC, further declined to 1% (P < 0.001). The overall rate of medical therapy for PDA was higher (P = 0.007) in the HS epoch; however, the need for definitive PDA closure by surgery or percutaneous route decreased (P < 0.001). There was also a reduced incidence of death in the first postnatal week (P = 0.027). After adjustment for confounders using logistic regression modeling GA at birth, maternal SSRI exposure, magnesium exposure, inborn status, dopamine treatment, and year of birth (model 1), and HS era (model 2) were independently associated with survival without sIVH. After adjusting for the interaction between HS and year of birth (model 3), there was a greater increase in odds of survival over time for HS compared with HC (OR, 1.41 vs. 0.99; P = 0.021) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Adverse Neonatal Outcomes

| Hemodynamic Screening (n = 191) | Historical Control Subjects (n = 423) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Composite of death/severe IVH | 29 (15) | 122 (29) | <0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Survival free of severe morbidity (NEC, grade III BPD, severe IVH) | 155 (81) | 264 (66) | <0.001 |

| Neurological | |||

| Severe IVH | 13 (7) | 81/402 (20) | <0.001 |

| All grades of IVH | 31/187 (17) | 123/393 (31) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory | |||

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (at 36 wk) | |||

| Ventilator dependent (grade III) | 11 (7) | 48 (13) | 0.02 |

| Noninvasive positive pressure (grade II) | 124 (74) | 219 (61) | 0.008 |

| Death/grade III BPD at 36 wk | 30 (17) | 124 (29) | 0.002 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage | 2 (1) | 15 (4) | 0.11 |

| Pneumothorax | 5 (3) | 36/415 (9) | 0.005 |

| Cardiovascular | |||

| PDA medical treatment | 139 (73) | 228/373 (61) | 0.007 |

| PDA intervention (surgery/percutaneous) | 48 (25) | 135/315 (65) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| Intestinal perforation | 11 (6) | 25 (6) | 0.94 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 2 (1) | 26 (6) | <0.001 |

| Ophthalmologic | |||

| Laser/bevacizumab treatment for ROP | 15/189 (8) | 20 (6) | 0.36 |

| Mortality characteristics | |||

| Death | 21 (12) | 76 (18) | 0.03 |

| Age at death | 13 [6, 38] | 7 [2, 22] | 0.07 |

| Death in the first postnatal week | 6 (3) | 37 (9) | 0.027 |

Definition of abbreviations: BPD = bronchopulmonary dysplasia; IVH = intraventricular hemorrhage; NEC = necrotizing enterocolitis; PDA = patent ductus arteriosus; ROP = retinopathy of prematurity.

Data are presented as median [interquartile range] or frequency (percent).

Figure 3.

Temporal changes in risk of death or severe intraventricular hemorrhage before and after introduction of hemodynamic screening. HS = hemodynamic screening; IVH = intraventricular hemorrhage; OR = odds ratio.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression to Adjust Survival without Severe Intraventricular Hemorrhage for Confounders

| Model 1 (AIC = 586.8) |

Model 2 (AIC = 584.7) |

Model 3 (AIC = 583.3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | P Value | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | P Value | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | P Value |

| Hemodynamic screening | — | — | 2.09 [1.19–3.66] | 0.01 | — | — |

| Birth year | 1.07 [1.01–1.13] | 0.028 | — | — | — | — |

| Birth year (pre-HS) | — | — | — | — | 0.99 [0.91–1.08]* | 0.794 |

| Birth year (HS) | — | — | — | — | 1.41 [1.10–1.81]* | 0.006 |

| Gestational age | 1.51 [1.30–1.76] | <0.0001 | 1.52 [1.31–1.76] | <0.0001 | 1.52 [1.31–1.77] | <0.0001 |

| Maternal SSRI exposure | 0.38 [0.16–0.88] | 0.024 | 0.35 [0.15–0.82] | 0.015 | 0.32 [0.13–0.76] | 0.010 |

| Magnesium exposure | 1.96 [1.24–3.10] | 0.004 | 1.83 [1.15–2.92] | 0.011 | 1.77 [1.12–2.82] | 0.015 |

| Inborn | 1.82 [1.05–3.14] | 0.033 | 1.84 [1.06–3.19] | 0.029 | 1.92 [1.10–3.34] | 0.021 |

| Dopamine treatment | 0.45 [0.27–0.74] | 0.002 | 0.48 [0.29–0.78] | 0.004 | 0.50 [0.30–0.82] | 0.006 |

Definition of abbreviations: AIC = Akaike information criterion; CI = confidence interval; HS = hemodynamic screening; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Between-epoch slope P = 0.021.

Discussion

The transitional period and first postnatal week represent a time of major adaptive changes that places the extremely preterm infant at increased risk of hemodynamic instability and end-organ morbidity resulting from intrinsic developmental vulnerability of the immature cardiovascular system. Although the approach to HS is not randomized, the merits of a structured, physiology-based approach that was universally followed within a center that has a long-standing standardized approach to respiratory and nutritional care are noteworthy. Individualized, physiology-guided care facilitated by TnECHO has been used to refine the approach to postoperative care after PDA ligation (21) and to identify a population of preterm infants at risk of BPD (22). In a retrospective cohort, TnECHO-derived physiological information changed management in approximately 40% of cases (23), and PDA screening in the first 72 hours has been associated with lower in-hospital mortality and pulmonary hemorrhage (24). In addition, although TnECHO in the first 72 hours has been shown to be safe, feasible, and associated with a low rate of sIVH (25), there is little data regarding the implications of physiology-guided care for early neurological morbidity. In this large cohort of extremely preterm infants born at <27 weeks, we demonstrated that the introduction of an early TnECHO screening program with physiology-targeted therapy was associated with a reduced risk of the composite of death or sIVH, among other major morbidities, such as severe BPD and NEC. It was notable that the proportion of 22–23-week neonates increased to 41% in the HS epoch. It is important to highlight that although the imaging was performed by neonatologists with hemodynamic expertise, these diagnostic assessments may be performed and interpreted by pediatric echocardiographers.

The biological determinants of sIVH are believed to be related to ischemia-reperfusion injury to the fragile germinal matrix, particularly because the forebrain vessels may not be considered a physiologically high priority during a state of compensated shock at the time of preterm birth (8). In addition to the previously referenced studies by Kluckow and Evans (7) and Noori and colleagues (26), each of which demonstrated a period of low followed by high systemic flow on echocardiography immediately preceding detection of IVH, other modalities have shown similar findings. The vulnerability of preterm infants in the transitional period was recently reiterated by Miletin and colleagues, who, using bioimpedance, demonstrated that patients with deranged hemodynamics on longitudinal monitoring were at higher risk of adverse outcomes (27). That the early transition represents a time period of increased vulnerability is not surprising; specifically, the increase in afterload, upon loss of the low-resistance placenta, increases the risk of impaired LV systolic performance and a low cardiac output state. The immature myocardium is poorly equipped to mount an adequate response to this change in loading conditions because of relatively disorganized myofibrils, an immaturity of calcium handling, and sparse contractile tissue. Therefore, it is biologically likely that cardiac dysfunction is a contributor to the early low-flow state that precedes IVH (7, 26).

The mechanism by which early TnECHO-guided care may mitigate the risk of sIVH and early mortality is likely multifactorial. First, early identification of heart dysfunction and use of low-dose positive inotropy to correct impaired cardiac function may reverse the conditions that contribute to the ischemia-reperfusion mechanism suspected to be a cause of IVH (7, 26). Second, hypotension is common in the transitional period, and dopamine-mediated vasoconstriction, driven predominantly by the traditional practice to increase blood pressure to arbitrary thresholds (9), is the typical therapeutic choice. Among neonates ⩽26 weeks, it has been shown that approximately one-third of patients are exposed to vasoactive medications. Of these, 83% received treatment on Postnatal Days 0–1 (28). Dopamine, which increases arterial pressure without necessarily increasing cardiac output (16, 29) and has been associated with impaired cerebral autoregulation (30), remains the commonest cardiotonic drug used in the NICU (28). Similarly, data from a large multicenter registry reported that dopamine was used more commonly than caffeine in infants born less than 25 weeks’ gestation (31). Therefore, decreased use of nonspecific systemic vasoconstrictors, dopamine in particular, in our study may also play a role by mitigating ischemia and primarily by reducing the reperfusion phase of brain injury (30). It is noteworthy that a lower rate of dopamine use in the HS epoch remained associated with a decreased rate of death or sIVH. We speculate, however, that the benefit is more likely to relate to earlier recognition of adverse cardiovascular disease states and the provision of treatment in a more precise manner, potentially avoiding the development of systemic hypotension. Third, screening TnECHO and early targeted acetaminophen may mitigate the secondary rise in cardiac output in patients with hsPDA, because the magnitude of the left-to-right shunt increases secondary to falling pulmonary vascular resistance. There are additional advantages to a targeted rather than a prophylactic approach to PDA treatment; specifically, HS demonstrated evidence of cardiovascular disease states (cardiac dysfunction, aPH, structural heart disease) in 18% of patients (n = 35 of 194) in whom PDA closure would be harmful.

Early modulation of PDA shunt may also play a role in several of the other improvements in neonatal morbidity observed in this cohort. Our data challenge recent trials of early PDA treatment, which have reported not only a lack of positive modulation of important outcomes such as BPD (32, 33) or cerebral palsy (34) but also that ibuprofen may increase the risk of BPD (32). These trials are limited by enrollment of patients based on an arbitrary threshold of PDA size, without adjudication of hemodynamic significance such that the likelihood of spontaneous closure is uncertain and potentially higher than expected. Our approach used a comprehensive scoring system, like in the El-Khuffash and colleagues trial (35), which demonstrated the existence of infants with a low PDA score who may be enrolled in trials on the basis of a diameter of 1.5 mm. Of note, these infants had a very low rate of need for later PDA treatment and BPD, which we speculate relates to a high rate of spontaneous closure. Chronic exposure to PDA shunt has been associated with a variety of morbidities, including BPD (36) and NEC (37). In addition, a concerning relationship between prolonged PDA exposure and pulmonary vascular maldevelopment has also been questioned (38–40). Overcirculation of the lungs during the canalicular stage of lung development, in combination with mechanical ventilation and other mediators, is associated with inflammatory lung disease and the development of BPD (41). Semberova and colleagues demonstrated that the median time to PDA closure was 71 days among neonates <26 weeks (42); however, Clyman and colleagues demonstrated that in a population of neonates <28 weeks at birth, 7–14-day exposure to hsPDA was sufficient to increase the OR of developing BPD to 2.1–3.9, respectively (43). This is in alignment with our data whereby the transition from active management beginning at a median of 6 to 0 postnatal days was associated with a reduced risk of severe BPD. There are likely to be synergistic benefits to the risk of pulmonary vascular disease and chronic pulmonary hypertension; however, mandatory echocardiography screening at 36 weeks’ GA was not performed in the prior epoch to allow a meaningful comparison. Similarly, NEC has been associated with prolonged exposure to a PDA shunt due to bowel hypoperfusion (37). Of note, the only randomized clinical trial of early PDA closure reported a significant reduction in NEC, although there were concerns regarding the high rate in the control arm (44). These effects were magnified in babies who were also fed early. Although the baseline rate was already relatively low, the near absence of NEC in the HS cohort is striking, particularly with the higher proportion of 22–23-week infants in the HS era. Similarly, the rate of early (first week) death was reduced from 50% to 25% of overall neonatal mortalities. Finally, it is useful to note that medical therapy increased while interventional closure decreased, suggesting an advantage of early therapy in avoidance of the need for surgical or percutaneous closure.

In interpreting these data, it is important to recognize three key factors. First, over the duration of the study period, there was a noticeable increase in factors associated with adverse pregnancy outcome, which should have naturally biased against improvement in neonatal outcomes. Although known confounders (e.g., historical advances in pregnancy care, magnesium sulfate, DCC) were considered as discrete variables, birth year was included in the final analysis to adjust for unknown factors that may have contributed to gradual advances in neonatal care. Even with year of birth included, HS remained a strong independent predictor of survival without sIVH. Second, it is important to note that from the outset of this cohort (2010), active management was practiced across the GA spectrum, thus negating any effect of nonresuscitation on the outcome of death. In fact, the population in which this study was performed was already a high-achieving NICU with a low rate of morbidity and mortality compared with similar institutions in the United States (45). That the benefits of physiology-guided care may be most applicable in situations where other variables (e.g., approach to ventilation, resuscitation) are optimized should be considered. Third, known protective factors such as GA, inborn status, and prophylactic magnesium were positively associated with a lower incidence of the primary outcome, whereas maternal SSRI use was negatively associated.

Limitations

As with all nonrandomized studies, there is a possibility that unaccounted for factors contributed to the improved outcomes seen in this cohort. The use of logistic regression with covariate interaction to evaluate the role of HS as a discrete entity minimizes the potentially confounding effect of time on the results. Second, the screening program was introduced as a complete package and was associated not only with a change in approach to one clinical problem but a holistic change in diagnostic and therapeutic strategy. This makes it challenging to distinguish what, if any, specific aspects of TnECHO-guided care were particularly associated with the improved outcomes. The lower use of early iNO, dopamine, and sodium bicarbonate and earlier use of acetaminophen to modulate the PDA shunt have interdependent effects that are difficult to tease out in this study but are worthy of further analyses. For example, the reduction in vasopressor-dependent hypotension, presumed to be mitigated by the closure of the PDA, with use of prophylactic indomethacin lends credence to these effects (46). In addition, there may be unmeasured effects of echocardiography-guided care, such as alterations in fluid balance or modification of mechanical ventilation, that are not accounted for in this analysis. Further evaluation of specific aspects may provide more guidance to programs that may seek to implement some but not all aspects of the program. In addition, limitations on the available echocardiography data from the HC epoch resulted in our inability to adjudicate some important neonatal outcomes, such as chronic pulmonary hypertension, as endpoints for this study. Our data collection was not exhaustive, and specific information about time to full enteral feeds, duration of mechanical ventilation, and late-onset use of steroids or pulmonary vasodilators was not collected. Because our approach to feeding and respiratory care is highly standardized, we do not anticipate any major confounding effect.

Conclusions

Introduction of an HS program consisting of early TnECHO and physiology-guided care to an already high-functioning NICU was associated with a reduced risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, including the composite of death/sIVH, severe BPD, and NEC. A shift away from primary vasopressors or fluid toward an inotrope-driven approach and a higher rate of medical therapy for hsPDA characterized the major changes in management. Further studies are required to evaluate the specific contributors to improved outcome and the impact across multiple centers, perhaps as a cluster randomized clinical trial. In the meantime, TnECHO-based, physiology-guided individualization may be an avenue toward lower early mortality and neurological injury.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH under award UL1TR002537.

Author Contributions: R.E.G.: design, data collection, analysis, writing first draft, and approving the final draft. T.C., A.R.B., J.A.S., A.C., M.B., A.H.S., and J.M.K.: design and approval of the final draft. P.T.E.: analysis and approval of the final draft. D.R.R. and P.J.M.: design, data collection, analysis, and approval of the final draft.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202212-2291OC on May 20, 2023

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Bell EF, Hintz SR, Hansen NI, Bann CM, Wyckoff MH, DeMauro SB, et al. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network Mortality, in-hospital morbidity, care practices, and 2-year outcomes for extremely preterm infants in the US, 2013-2018. JAMA . 2022;327:248–263. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.23580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Handley SC, Passarella M, Lee HC, Lorch SA. Incidence trends and risk factor variation in severe intraventricular hemorrhage across a population based cohort. J Pediatr . 2018;200:24–29.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Persad N, Kelly E, Amaral N, Neish A, Cheng C, Fan CS, et al. Impact of a “brain protection bundle” in reducing severe intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants <30 weeks GA: a retrospective single centre study. Children (Basel) . 2021;8:983. doi: 10.3390/children8110983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Al-Haddad BJS, Bergam B, Johnson A, Kolnik S, Thompson T, Perez KM, et al. Effectiveness of a care bundle for primary prevention of intraventricular hemorrhage in high-risk neonates: a Bayesian analysis. J Perinatol . 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41372-022-01545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Radic JA, Vincer M, McNeely PD. Outcomes of intraventricular hemorrhage and posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus in a population-based cohort of very preterm infants born to residents of Nova Scotia from 1993 to 2010. J Neurosurg Pediatr . 2015;15:580–588. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.PEDS14364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ballabh P. Pathogenesis and prevention of intraventricular hemorrhage. Clin Perinatol . 2014;41:47–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kluckow M, Evans N. Low superior vena cava flow and intraventricular haemorrhage in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 2000;82:F188–F194. doi: 10.1136/fn.82.3.F188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Noori S, Seri I. Hemodynamic antecedents of peri/intraventricular hemorrhage in very preterm neonates. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med . 2015;20:232–237. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stranak Z, Semberova J, Barrington K, O’Donnell C, Marlow N, Naulaers G, et al. HIP consortium International survey on diagnosis and management of hypotension in extremely preterm babies. Eur J Pediatr . 2014;173:793–798. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giesinger RE, Fellows M, Rios DR, McNamara PJ.2021.

- 11. Richardson DK, Corcoran JD, Escobar GJ, Lee SK. SNAP-II and SNAPPE-II: simplified newborn illness severity and mortality risk scores. J Pediatr . 2001;138:92–100. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.109608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davidson J, Tong S, Hancock H, Hauck A, da Cruz E, Kaufman J. Prospective validation of the vasoactive-inotropic score and correlation to short-term outcomes in neonates and infants after cardiothoracic surgery. Intensive Care Med . 2012;38:1184–1190. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2544-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mertens L, Seri I, Marek J, Arlettaz R, Barker P, McNamara P, et al. Writing Group of the American Society of Echocardiography; European Association of Echocardiography; Association for European Pediatric Cardiologists Targeted neonatal echocardiography in the neonatal intensive care unit: practice guidelines and recommendations for training. Writing Group of the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) in collaboration with the European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) and the Association for European Pediatric Cardiologists (AEPC) J Am Soc Echocardiogr . 2011;24:1057–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rios DR, Martins FF, El-Khuffash A, Weisz DE, Giesinger RE, McNamara PJ. Early role of the atrial-level communication in premature infants with patent ductus arteriosus. J Am Soc Echocardiogr . 2021;34:423–432.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dagle JM, Rysavy MA, Hunter SK, Colaizy TT, Elgin TG, Giesinger RE, et al. Iowa Neonatal Program Cardiorespiratory management of infants born at 22 weeks’ gestation: The Iowa approach. Semin Perinatol . 2022;46:151545. doi: 10.1016/j.semperi.2021.151545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osborn D, Evans N, Kluckow M. Randomized trial of dobutamine versus dopamine in preterm infants with low systemic blood flow. J Pediatr . 2002;140:183–191. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.120834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higgins S, Friedlich P, Seri I. Hydrocortisone for hypotension and vasopressor dependence in preterm neonates: a meta-analysis. J Perinatol . 2010;30:373–378. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr . 1978;92:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Juhl SM, Hansen ML, Gormsen M, Skov T, Greisen G. Staging of necrotising enterocolitis by Bell’s criteria is supported by a statistical pattern analysis of clinical and radiological variables. Acta Paediatr . 2019;108:842–848. doi: 10.1111/apa.14469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jensen EA, Dysart K, Gantz MG, McDonald S, Bamat NA, Keszler M, et al. The diagnosis of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very preterm infants: an evidence-based approach. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;200:751–759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201812-2348OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Resende MH, More K, Nicholls D, Ting J, Jain A, McNamara PJ. The impact of a dedicated patent ductus arteriosus ligation team on neonatal health-care outcomes. J Perinatol . 2016;36:463–468. doi: 10.1038/jp.2015.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. El-Khuffash A, James AT, Corcoran JD, Dicker P, Franklin O, Elsayed YN, et al. A patent ductus arteriosus severity score predicts chronic lung disease or death before discharge. J Pediatr . 2015;167:1354–1361.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. El-Khuffash A, Herbozo C, Jain A, Lapointe A, McNamara PJ. Targeted neonatal echocardiography (TnECHO) service in a Canadian neonatal intensive care unit: a 4-year experience. J Perinatol . 2013;33:687–690. doi: 10.1038/jp.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rozé JC, Cambonie G, Marchand-Martin L, Gournay V, Durrmeyer X, Durox M, et al. Hemodynamic EPIPAGE 2 Study Group Association between early screening for patent ductus arteriosus and in-hospital mortality among extremely preterm infants. JAMA . 2015;313:2441–2448. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Deshpande P, Jain A, Ibarra Ríos D, Bhattacharya S, Dirks J, Baczynski M, et al. Combined multimodal cerebral monitoring and focused hemodynamic assessment in the first 72 h in extremely low gestational age infants. Neonatology . 2020;117:504–512. doi: 10.1159/000508961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Noori S, McCoy M, Anderson MP, Ramji F, Seri I. Changes in cardiac function and cerebral blood flow in relation to peri/intraventricular hemorrhage in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr . 2014;164:264–270.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miletin J, Semberova J, Martin AM, Janota J, Stranak Z. Low cardiac output measured by bioreactance and adverse outcome in preterm infants with birth weight less than 1250 g. Early Hum Dev . 2020;149:105153. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miller LE, Laughon MM, Clark RH, Zimmerman KO, Hornik CP, Aleem S, et al. Vasoactive medications in extremely low gestational age neonates during the first postnatal week. J Perinatol . 2021;41:2330–2336. doi: 10.1038/s41372-021-01031-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang J, Penny DJ, Kim NS, Yu VY, Smolich JJ. Mechanisms of blood pressure increase induced by dopamine in hypotensive preterm neonates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed . 1999;81:F99–F104. doi: 10.1136/fn.81.2.f99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Munro MJ, Walker AM, Barfield CP. Hypotensive extremely low birth weight infants have reduced cerebral blood flow. Pediatrics . 2004;114:1591–1596. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dempsey E, Rabe H. The use of cardiotonic drugs in neonates. Clin Perinatol . 2019;46:273–290. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hundscheid T, Onland W, Kooi EMW, Vijlbrief DC, de Vries WB, Dijkman KP, et al. BeNeDuctus Trial Investigators Expectant management or early ibuprofen for patent ductus arteriosus. N Engl J Med . 2023;388:980–990. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. El-Khuffash A, Bussmann N, Breatnach CR, Smith A, Tully E, Griffin J, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of early targeted patent ductus arteriosus treatment using a risk based severity score (the PDA RCT) J Pediatr . 2021;229:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rozé JC, Cambonie G, Le Thuaut A, Debillon T, Ligi I, Gascoin G, et al. Effect of early targeted treatment of ductus arteriosus with ibuprofen on survival without cerebral palsy at 2 years in infants with extreme prematurity: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr . 2021;233:33–42.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bussmann N, Smith A, Breatnach CR, McCallion N, Cleary B, Franklin O, et al. Patent ductus arteriosus shunt elimination results in a reduction in adverse outcomes: a post hoc analysis of the PDA RCT cohort. J Perinatol . 2021;41:1134–1141. doi: 10.1038/s41372-021-01002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Altit G, Saeed S, Beltempo M, Claveau M, Lapointe A, Basso O. Outcomes of extremely premature infants comparing patent ductus arteriosus management approaches. J Pediatr . 2021;235:49–57.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dollberg S, Lusky A, Reichman B. Patent ductus arteriosus, indomethacin and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants: a population-based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:184–188. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200502000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. El-Khuffash A, Mullaly R, McNamara PJ. Patent ductus arteriosus, bronchopulmonary dysplasia and pulmonary hypertension—a complex conundrum with many phenotypes? Pediatr Res . 2023 doi: 10.1038/s41390-023-02578-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McNamara PJ, Lakshminrusimha S. Maldevelopment of the immature pulmonary vasculature and prolonged patency of the ductus arteriosus: association or cause? Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;207:814–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202211-2146ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gentle SJ, Travers CP, Clark M, Carlo WA, Ambalavanan N. Patent ductus arteriosus and development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2023;207:921–928. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202203-0570OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Willis KA, Weems MF. Hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus and the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Congenit Heart Dis . 2019;14:27–32. doi: 10.1111/chd.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Semberova J, Sirc J, Miletin J, Kucera J, Berka I, Sebkova S, et al. Spontaneous closure of patent ductus arteriosus in infants ⩽ 1500 g. Pediatrics . 2017;140:e2014258. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-4258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Clyman RI, Hills NK, Liebowitz M, Johng S. Relationship between duration of infant exposure to a moderate-to-large patent ductus arteriosus shunt and the risk of developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia or death before 36 weeks. Am J Perinatol . 2020;37:216–223. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cassady G, Crouse DT, Kirklin JW, Strange MJ, Joiner CH, Godoy G, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of very early prophylactic ligation of the ductus arteriosus in babies who weighed 1000 g or less at birth. N Engl J Med . 1989;320:1511–1516. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906083202302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Watkins PL, Dagle JM, Bell EF, Colaizy TT. Outcomes at 18 to 22 months of corrected age for infants born at 22 to 25 weeks of gestation in a center practicing active management. J Pediatr . 2020;217:52–58.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liebowitz M, Koo J, Wickremasinghe A, Allen IE, Clyman RI. Effects of prophylactic indomethacin on vasopressor-dependent hypotension in extremely preterm infants. J Pediatr . 2017;182:21–27.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]