Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Comorbidities in people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) may negatively impact injury recovery course and result in long-term disability. Despite the high prevalence of several categories of comorbidities in TBI, little is known about their association with patients’ functional outcomes. We aimed to systematically review the current evidence to identify comorbidities that affect functional outcomes in adults with TBI.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION:

A systematic search of Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase and PsycINFO was conducted from 1997 to 2020 for prospective and retrospective longitudinal studies published in English. Three researchers independently screened and assessed articles for fulfillment of the inclusion criteria. Quality assessment followed the Quality in Prognosis Studies tool and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network methodology recommendations.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS:

Twenty-two studies of moderate quality discussed effects of comorbidities on functional outcomes of patients with TBI. Cognitive and physical functioning were negatively affected by comorbidities, although the strength of association, even within the same categories of comorbidity and functional outcome, differed from study to study. Severity of TBI, sex/gender, and age were important factors in the relationship. Due to methodological heterogeneity between studies, meta-analyses were not performed.

CONCLUSIONS:

Emerging evidence highlights the adverse effect of comorbidities on functional outcome in patients with TBI, so clinical attention to this topic is timely. Future research on the topic should emphasize time of comorbidity onset in relation to the TBI event, to support prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation. PROSPERO registration (CRD 42017070033).

Keywords: Cognition, Recovery of function, Systematic review, Comorbidity, Prognosis

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of disability due to physical and cognitive impairments that interfere with family, social, and/or occupational functioning.1, 2 It is estimated that over 50 million individuals sustain a TBI each year, worldwide.3 There has been increasing interest in identifying factors related to functional outcomes post-TBI with the evolution of a patient-centered, systems biology approach to care, where the individual’s physiological, cognitive, emotional, and physical function are captured simultaneously in assessing treatment and rehabilitation needs of the patient.4 Previous research has reported variations in outcomes according to injury severity,5, 6 age,7–10 and sex/gender.11–14 Sex (i.e., biological attributes in humans)15 and gender (i.e., socially constructed roles and responsibilities)15 are strongly interrelated yet distinct constructs that have rarely been studied separately. Furthermore, the terms “sex” and “gender” have been used interchangeably in literature to date.16 To avoid misrepresenting information in included articles, we will use the term ‘sex/gender’ and designations of male and female persons/patients/adults when reporting aggregated results in this evidence synthesis. Interest in comorbidities of TBI, defined as disorders that are present in addition to the index condition,17 is increasing. It has become apparent that TBI is not a single event, but an enduring disease process, co-occurring with multiple disorders that may increase the risk of adverse clinical course and poor recovery and functional outcomes postinjury,18–21 independent of age, sex/gender and acute injury severity markers. Current evidence not only suggests that persons with TBI are at greater risk of developing comorbidities as time since injury progresses, including medical and psychiatric disorders, but also that the probability of sustaining a TBI is greater in persons with pre-existing disorders.22, 23 Further, the presence or absence of comorbid disorders has been observed to be a differentiating factor of having low or high cognitive and motor functional independence measure (FIM) scores’ trajectories during inpatient rehabilitation.24 One study demonstrated comorbidities such as hypertension (HPT), diabetes mellitus (DM), cancer, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and anxiety to be significantly associated with motor independence (i.e., FIM motor); whereas, diabetes, cancer, chronic bronchitis, anxiety, and depression were associated with cognitive recovery trajectories (FIM cognition).25 The array of comorbidities and their varying impact on cognitive and/or physical function can alter treatment plans and rehabilitation outcomes, as observed in a comparable population of multiple sclerosis.26 As such, the functional outcomes of individuals with TBI are likely to be determined by comorbid disorders that need to be comprehensively studied.27 To date, no attempt has been made to systematically review literature on the topic of how comorbidities impact functional outcomes in persons with TBI.28 To address the gap in scientific knowledge and inform clinical decision making,29 this evidence synthesis was initiated with the aim to: 1) describe types and frequency of comorbidities in adult patients with TBI; 2) assess the association between comorbidity and any aspect of physical and/or cognitive functioning after TBI and over time; and 3) offer an evidence-based discussion of the relevance of comorbidity to post-TBI functioning, considering age, sex/gender, and injury severity, where possible.

Evidence acquisition

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD 42017070033) and the protocol was published in a peer-review open access journal.28 The findings were reported in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All prospective and retrospective longitudinal design studies with a focus on physical and/or cognitive outcomes and assessment of comorbidity in adult persons diagnosed with TBI, were considered eligible. The definition of adulthood varied across studies included in this review, therefore the decision was made to include all studies whose minimum sample age or whose mean minus standard deviation of the sample was 16 years of age or older. Letters to editors, reviews without data, case reports, conference abstracts, articles without primary data, studies that focus on therapeutic interventions, and theses, were excluded.28

Data source and searches

A systematic search strategy for MEDLINE (Medline in Process, ePubs and Medline Daily), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, and PsycINFO, was developed in collaboration with a Medical Information Specialist, and covered the time period of May 1997 to September 2020. The medical subject headings (MeSH) for Medline were “brain injury,” “comorbidity,” “risk adjustment” and “functioning.” The full electronic search strategy can be found in Supplementary Digital Material 1: Supplementary Text File 1. Physical functioning incorporates activities such as ambulating, eating, bathing, dressing and other activities, to quantify functional status in activities of daily living.30 Cognitive functioning includes aspects of communication, perception, thinking, reasoning, and remembering.31

Data extraction and quality assessment

Three researchers (SH and CX or SH and TM) independently reviewed abstracts/study titles and subsequently screened them for eligibility. Publications that met the inclusion criteria were assessed using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool for risk of bias in studies of prognoses.32 Through the utilization of the QUIPS tool, two researchers (SH, CX) independently (1) assessed the articles in terms of seven elements as potential sources of biases including, study participation, study design, study attrition, prognostic factors, outcome measures, confounders, and analysis and (2) graded the presence of potential bias as “yes,” “partly,” “no” or “unsure”. Following these steps, the overall level of potential bias for each study was summarized in accordance with the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network methodology,33 where we assigned: 1) “++” when all of the seven quality criteria were fulfilled (allowing one “Partly” during assessment); 2) “+” when four to six of the criteria were met; and 3) “−” when fewer than four criteria were fulfilled. Categories (1) are denoted as “high-quality studies;” (2) as “moderate-quality studies;” and (3) as “low-quality studies.” Given that retrospective cohort study design is typically ranked lower in evidence than prospective cohort study design, if a rating of “++” was achieved, it was degraded to a “+.” The results of studies with sufficient quality (i.e., ‘high’ [++] and ‘moderate’ [+] quality studies) were included for data abstraction and syntheses. Any discrepancy between reviewers was resolved by a third researcher (TM).

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were extracted from each included study and incorporated the following: study design, source of study data, participants’ characteristics, attrition rate, sample size, baseline assessment, duration of follow-up period, the definitions of TBI and comorbidity, the definition of outcome and timing of measurements, the statistical analysis used, and a comment section. In addition, data on the magnitude of the association between comorbidities and functional outcome were extracted, as reported by the authors, along with the variables included in analyses. The heterogeneity in population characteristics, study design, types and measurements used to assess comorbidity and functional outcome and TBI ruled out the utility of a meta-analysis. We therefore used a best-evidence synthesis approach, synthesizing findings from included studies through tabulation and qualitative description.34

Evidence synthesis

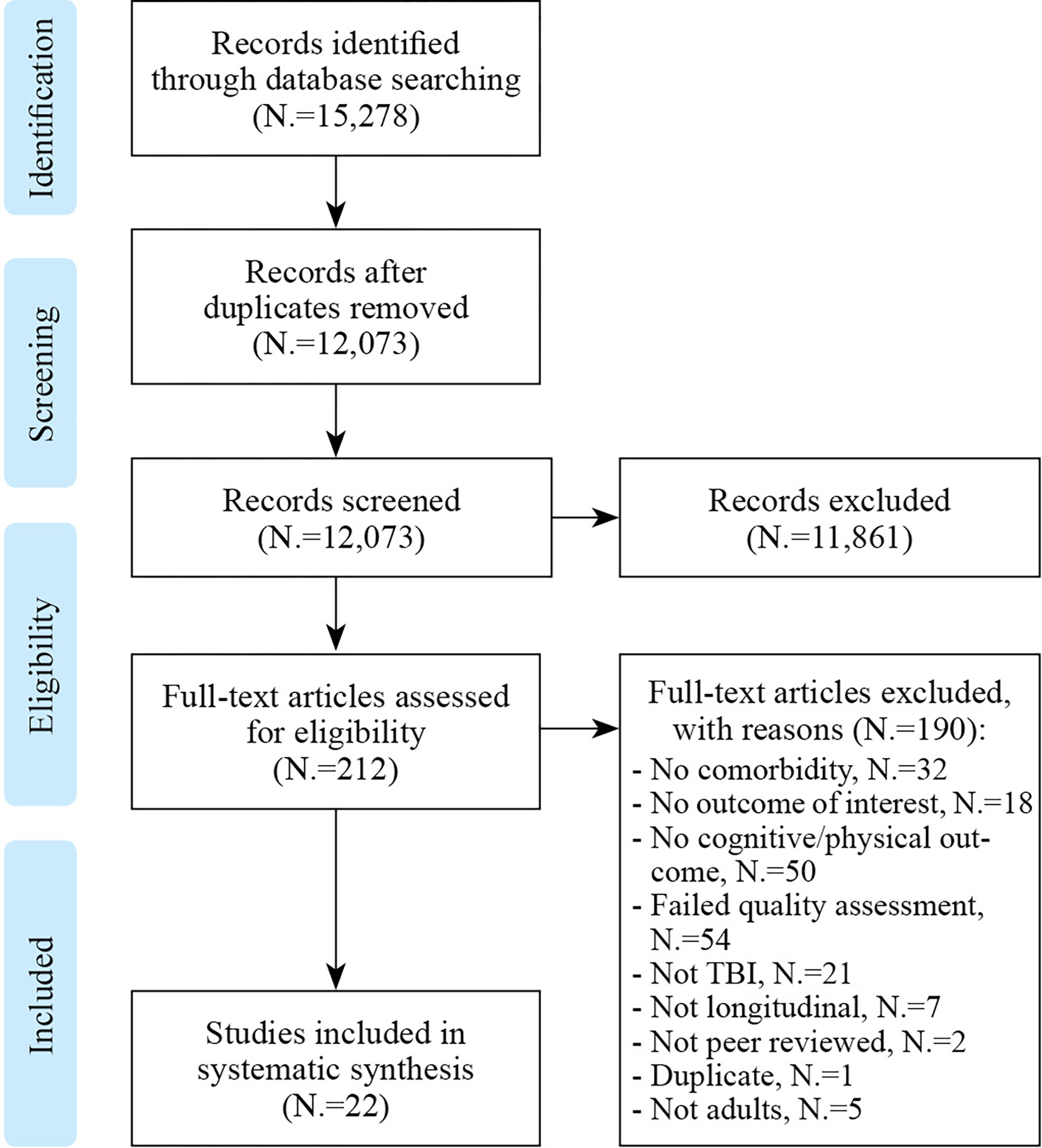

A total of 15,278 citations were abstracted from databases searched. After removal of duplicates, a total of 12,073 articles remained. Following eligibility screening and quality assessment, 22 articles, all moderate quality, were included. The studies’ samples ranged from 74 to 811,622 participants. Figure 1 and Table I25, 35–55 present the study selection process and characteristics of included studies, respectively. Summary of data extraction, reasons for exclusion and quality assessment can be found in Supplementary Digital Material 2: Supplementary Table I–III, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow chart documenting the process of article selection.

Table I.

Characteristics of included studies (N.=22).

| Year | Author(s) | Country | Sample size | Population | Comorbidity | Outcome | Follow-up | Analysis* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 2014 | Barnes et al.35 | USA | 188,764 | Adult veterans with TBI 96% males | Depression, CVD, PTSD | Dementia | 7.44 years (mean) | Survival analysis, cumulative incidence |

| 2020 | Chan et al.36 | Canada | 5,802 | Adults with TBI, 64% males | 43 factors of preinjury health status | RFG | At discharge | Sex-specific multivariable linear regression |

| 2015 | Chao et al.37 | Taiwan | 107 | Adults with moderate TBI, 60% males | Osteoporosis (OSTA Index) | GOS | At discharge | Multiple regression |

| 2019 | Corrigan et al.38 | usA | 407 | Adults with TBI, 74% males | HPT, drug and alcohol use, depression, anxiety, DM, cardiac conditions, and respiratory disorders | FIM motor & cognitive scores | 5 years | Multivariate regression |

| 2014 | Henninger et al.39 | usA | 136 | Adults with TBI, 60% males | Severe leukoaraiosis, DM | mRS, GOS | 3-and 6-months |

Multivariable logistic regression model with stepwise backward elimination |

| 2020 | Humphries et al.40 | UK | 1,322 | Adults with TBI, 68% males | Medical comorbidity (CIRS), psychiatric history, alcohol use | GOS-E | 12-months | Multi-ordinal regression |

| 2019 | Kumar et al.41 | usA | 2,134 | Adults with moderate to severe TBI, 67% males | Comorbidity clusters (i.e., acute hospital complications, chronic disease, substance abuse or dependence | FIM efficiency, GOS-E |

12-months | Multivariable linear and logistic regression |

| 2020 | Latronico et al.42 | Italy | 143 | Adults with moderate or severe TBI, 81% males | PTCI, hypotension, hypoxia | GOS | 6-months | Multiple proportional odds logistic regression |

| 2019 | Lenell et al.43 | Sweden | 220 | Adults with TBI, 72% males | Brain injury/disease, history of TBI, DM, HPT/CV, alcohol use | GOS-E | 7.8-months (mean) |

Multivariate logistic regression |

| 2012 | Lin et al.44 | Taiwan | 117 | Adults with tSAH, 79% males | Vasospasm | GOS | 6-months | Multivariate |

| 2015 | Lingsma et al.45 | USA | 386 | Adults with mild TBI, 70% males | Psychiatric medical history, hypotension, hypoxia | GOS-E | 3- and 6-months | Multi-variable proportional odds regression models |

| 2020 | Maiden et al.46 | Australia | 540 | Adults with severe TBI, 55% males | Charlson comorbidity index, hypotension | GOS-E | 6-months | Multivariate regression model |

| 2019 | Malec et al.25 | USA | 404 | Adults with TBI, 76% males | HPT, DM, cancer, anxiety, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic bronchitis, depression | FIM motor and cognitive scores | 10 years | Linear mixed-effects models |

| 2006 | Marino et al.47 | Italy | 89 | Adults with moderate or severe TBI, 88% males | PTCI | GOS | 6-months | Multivariable logistic regression |

| 2019 | Mollayeva et al.48 | Canada | 712,708 | Adults with TBI, 59% males | Comorbid spinal cord injury | Dementia | 52-months (median) | Generic and sex-stratified multivariable cox regression model |

| 2014 | Nordstrom et al.49 | Sweden | 811,622 | Male adults (military) with mild or severe TBI, 100% males | Depression | Young onset dementia | 33 years (median) | Logistic regression model |

| 2019 | Seno et al.50 | Japan | 83 | Adults with mild TBI, 52% males | HPT, DM, dementia, cancer | GOS | At discharge | Multivariable logistic regression model with stepwise backward elimination |

| 2017 | Shibahashi et al.51 | Japan | 74 | Adults with TBI, 71% males | Sarcopenia | GOS | 6-months | Multivariable logistic regression |

| 2006 | Turner et al.52 | USA | 124 | Adults with TBI, 84% males | Alcohol use | NCSE; Trailmaking test, part A and B, RAVLT; RCF | 24.4 days ±19.7 after injury | Hierarchical multiple regression |

| 2012 | Thompson et al.53 | usA | 196 | Adults with TBI, 71% males | Elixhauser comorbidity index | mFIM | At discharge | Linear regression |

| 2009 | Utomo et al.54 | Australia | 310 | Adults with moderate or severe TBI, 55% males | charlson comorbidity index, SBP | GOS-E | 6-months | Multivariate backward stepwise logistic regression |

| 2019 | Yue et al.55 | USA | 260 | Adults with mild TBI. 70% males | Cardiac-HPT, cardiac-structural/ischemic/valvular, DM, gastrointestinal, hematological, headache/migraine, hepatic, pulmonary, psychiatric, renal, seizure, thyroid | GOS-E | 3- and 6-months | Multivariate logistic regression |

CV: cardiovascular disease; CVD: cerebrovascular disease; CIRS: Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; DM: diabetes mellitus; FIM:Functional Independence Measure; GOS: Glasgow Outcome Scale; GOS-E: Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended; HPT: Hypertension; mRS: modified rankin scale; mFIM: modified functional independence measure; NCSE: Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination; OSTA Index: Osteoporosis Self-assessment tool for asians; PTCI: posttraumatic cerebral infarction; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; RFG: relative functional gain; RAVLT: rey auditory verbal learning test; RCF: rey complex figure test; SBP: systolic blood pressure; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome; TBI: traumatic brain injury; tSAH: traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage.

As reported by researchers.

Study characteristics

Out of 22 studies, eleven studies originated in North America,25, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41, 45, 48, 52, 53, 55 two studies each in Taiwan,37, 44 Japan,50, 51 Sweden,43, 49 Australia,46, 54 and Italy,42, 47 and one study in the United Kingdom.40 Ten of the 22 studies were prospective cohort studies,25, 38, 40–45, 52, 55 and the remaining 12 were retrospective studies.35–37, 39, 46–51, 53, 54

Eleven studies included participants of various injury severities(i.e., mild, moderate and severe).25, 36, 38–40, 43, 44, 48, 51–53 Other studies focused on participants with specified severity - mild TBI,45, 50, 55 moderate TBI,37 severe TBI,46 both mild and severe,49 both moderate and severe41, 42, 47, 54 or did not report on TBI severity.35 The measurements used to determine TBI severity were the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS);25, 39–42, 44, 45, 47, 50–52, 55 a combination of GCS, Injury Severity Score (ISS), New Injury Severity Score (NISS), Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), AIS for head, and CT grading according to the Marshall classification;37, 43, 46, 53 the International Classification of Diseases (ICD);35, 48, 49 the Comprehensive Severity Index;38 the AIS for head and face;36 and the AIS.54

The nature of our research question concerns comorbidity in the TBI population as a prognostic factor of functional outcomes. This raises the issue of zero-time bias. In prognostic studies, testing should start at a defined point, called zero time. Designated zero times (i.e., baseline or first assessment) varied between studies included in this review.

Eighteen out of 22 studies reported hospital admission as their baseline assessment;25, 35, 37–39, 41–43, 45–48, 50–55 one study looked at health status five years preceding TBI index date,36 one study at ≤23 days postinjury,44 one study at six-weeks postinjury,40 and the remaining study used conscription registry date.49 In terms of the follow-up period, four studies had the date of discharge as their second point of assessment,36, 37, 50, 53 while 18 studies used a specific time point such as three-, six-, 12-months, 24-months, five years, 10 years, or another time point as their follow-up.25, 35, 38–49, 51, 52, 54, 55

Comorbidity assessment

Comorbid conditions that were examined in selected studies fall within the following categories: systemic medical diseases and other (i.e., arrythmia,39 asthma,25 cancer,25, 39, 50, 51 cardiac conditions,25, 38 cardiac-structural/ischemic/valvular,55 cataracts,25 chronic bronchitis,25 chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder,25 congestive heart failure,25, 39 coronary artery disease,39 deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism,39 DM,25, 38, 39, 43, 50, 51, 55 dyslipidemia,39 emphysema,25 fractures (hip/wrist/spine),25 gastrointestinal,55 goiter,25 hay fever,25 hematological,39, 55 hepatic disease,25, 39, 51, 55 HPT,25, 38, 39, 50, 51 HPT/cardiovascular disease [CV],43, 55 hypothyroidism,39 thyroid disease,25, 55 ischemic heart disease,51 kidney stones,25 lupus,25 myocardial infarction,25, 39 osteoporosis,25, 37 osteoarthritis,25 peripheral vascular disease,39 pulmonary disease,39, 51, 55 renal disease,39, 51, 55 respiratory disorders,38 RA,25 sarcopenia51); psychiatric and psychological disorders (i.e., alcohol use,25, 39, 40, 43, 45, 49, 52 anorexia,25 anxiety,25, 38 attention-deficit disorder/attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder,25 autism,25 bipolar disorder,25 bulimia,25 other eating disorder,25 depression,25, 35, 38, 49 drug use,25, 39, 49 alcohol and drug use,38 narcolepsy,25 non-specified psychiatric conditions,40, 45, 55 obsessive compulsive disorder,25 panic attacks,25 post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD],25, 35 psychosis,25 schizophrenia25); neurological and nervous system disorders (i.e., brain injury/disease,43 cerebrovascular disease (CVD),35 posttraumatic cerebral infarction (PTCI),42, 47 dementia,25, 39, 50 movement disorder,25 severe leukoaraiosis (e.g., abnormal change in appearance of white matter near the lateral ventricles),39 seizure,55 sleep disorder,25 spinal cord injury [SCI],48 stroke,25, 39, 49, 51 history of TBI43); clinical signs - potential precursor or indication of a disease (i.e., diastolic blood pressure [DBP],39 headache/migraine,55 high blood cholesterol,25 hypotension,39, 42, 45, 46 hypoxia,39, 42, 45 systolic blood pressure [SBP],39, 49, 54 vasospasm44); and frequency of comorbid disorders measured through indices (i.e., Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI],46, 54 Elixhauser Score Index [ESI]53). Comorbidity was also investigated using three comorbidity clusters (i.e., acute hospital complications, chronic disease, substance abuse),41 the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS),40 and 43 health status factors preceding TBI, that emerged from data mining.36

Outcome assessment

We included studies that examined functional outcome in relation to global functioning, or cognitive and/or physical functioning.56 Eighteen studies focused on global functioning; seven used Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS)37, 39, 42, 44, 47, 50, 51 with one study looking at both GOS the Modified Rankin Scale (mRS),39 six used Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended (GOS-E),40, 43, 45, 46, 54, 55 and five studies used FIM, specifically examining FIM motor and cognitive scores separately,25, 38 FIM efficiency (i.e., [total FIM discharge] – [total FIM admission]/rehabilitation length of stay) and GOS-E,41 relative functional gain (RFG) (i.e., (total FIM discharge) - (total FIM admission)]/maximum possible change in FIM),36 and the Modified FIM (mFIM).53 The GOS is a global scale for functional outcome that comprises of five categories: dead (1); vegetative state (2); severe disability (3); moderate disability (4); or good recovery (5).57 Similarly the GOS-E utilizes eight categories to measure outcome: dead (1); vegetative state (2); lower severe disability (3); upper severe disability (4); lower moderate disability (5); upper moderate disability (6); lower good recovery (7); and upper good recovery (8).58 The mRS is a patient reported outcome measure which categorizes level of functional independence, with reference to preinjury activities. The score ranges from perfect health without symptoms (scored as 0) to death (scored as 6).59, 60 The FIM measures cognitive and physical disability using 18 items, across six domains (i.e., self-care, sphincter control, mobility, locomotion, communication, social cognition) on a 7-point ordinal scale, ranging from complete dependence to complete independence.61, 62 The mFIM consists of three items; locomotion, feeding, and communication, each rated on a scale of 1 (total dependence) to 4 (total independence).63 Four studies focused on cognitive status as their functional outcome of interest, including dementia,35, 48, 49 and specific aspects of cognitive performance utilizing the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination (NCSE), the Trail Making Test, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT), and Rey Complex Figure Test (RCF).52 No study focused solely on physical functioning as an outcome of interest.

Confounding variables

In order to assess whether comorbidity was independently associated with functional outcome, 15 studies adjusted their results for sex/gender and age,25, 36, 37, 40, 41, 43, 44, 46–48, 50–53, 55 two of which stratified their results by sex/gender;36, 48 one study adjusted their results for just sex/gender;38 and five studies adjusted for just age.39, 42, 45, 49, 54 Eighteen studies adjusted their results for injury severity;36–48, 51–55 three of which only adjusted for motor GCS score.42, 43, 51 One study did not report on the confounding variables considered in the analysis.35

Relationship of comorbidity and outcome

Table II25, 35–55 presents a summary of examined comorbid health conditions, many of which have been explored in multiple studies and Supplementary Digital Material 3: Supplementary Table IV.—presents effect size of studied associations. In this review, effect size refers to the magnitude of association between comorbidities and functional outcome as reported by authors, utilizing either unstandardized or standardized statistical approaches.64

Table II.

Summary of comorbid disorders.

| Comorbid Disorders | Author(s) and Citation |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Systemic medical diseases and other | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.;39 Corrigan et al.;38 Yue et al.;55 Shibahashi et al.;51 Seno et al.;50 Lenell et al.43 |

| Hypertension | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.;39 Corrigan et al.;38 Shibahashi et al.;51 Seno et al.50 |

| Cancer | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.;39 Shibahashi et al.;51 Seno et al.50 |

| Hepatic disease | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.;39 Yue et al.;55 Shibahashi et al.51 |

| Pulmonary disease | Henninger et al.;39 Yue et al.;55 Shibahashi et al.51 |

| Renal disease | Henninger et al.;39 Yue et al.;55 Shibahashi et al.51 |

| Cardiac conditions | Malec et al.;25 Corrigan et al.38 |

| Hypertension/Cardiovascular disease | Yue et al.;55 Lenell et al.43 |

| Myocardial infarction | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.39 |

| Congestive heart failure | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al39 |

| Hematological | Henninger et al.;39 Corrigan et al.38 |

| Osteoporosis (OSTA Index) | Malec et al.;25 Chao et al.37 |

| Thyroid disease | Malec et al.;25 Yue et al.;55 |

| Coronary artery disease | Henninger et al.39 |

| Cardiac-structural/ischemic/valvular | Yue et al.55 |

| Arrhythmia | Henninger et al.39 |

| Asthma | Malec et al.25 |

| Chronic bronchitis | Malec et al.25 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder | Malec et al.25 |

| Emphysema | Malec et al.25 |

| Respiratory disorders | corrigan et al.38 |

| Ischemic heart disease | shibahashi et al.51 |

| Gastrointestinal | Yue et al.55 |

| Kidney stone | Malec et al.25 |

| Dyslipidemia | Henninger et al.39 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | Henninger et al.39 |

| Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism | Henninger et al.39 |

| Hypothyroidism | Henninger et al.39 |

| Goiter | Malec et al.25 |

| Sarcopenia | shibahashi et al.51 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Malec et al.25 |

| Osteoarthritis | Malec et al.25 |

| Fractures (hip/wrist/spine) | Malec et al.25 |

| Hay fever | Malec et al.25 |

| Cataracts | Malec et al.25 |

| Lupus | Malec et al.25 |

| Psychiatric and psychological disorders | |

| Alcohol use | Malec et al.;25 Lingsma et al.;45 Turner et al.;52 Henninger et al.;39 Nordström et al.;49 Lenell et al.;43 Humphries et al.40 |

| Depression | Malec et al.;25 Barnes et al.;35 corrigan et al.;38 Nordström et al.49 |

| Non-specified psychiatric conditions | Lingsma et al.;45 Yue et al.;55 Humphries et al.40 |

| Illicit drug use | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.;39 Nordström et al.49 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | Malec et al.;25 Barnes et al35 |

| Anxiety | Malec et al.;25 Corrigan et al.38 |

| Alcohol and drug use | Corrigan et al.38 |

| Bipolar disorder | Malec et al.25 |

| Schizophrenia | Malec et al.25 |

| Psychosis | Malec et al.25 |

| Anorexia | Malec et al.25 |

| Bulimia | Malec et al.25 |

| Other eating disorder | Malec et al.25 |

| Attention-deficit disorder/Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | Malec et al.25 |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | Malec et al.25 |

| Autism | Malec et al.25 |

| Panic attacks | Malec et al.25 |

| Narcolepsy | Malec et al.25 |

| Neurological and nervous system disorders | |

| Stroke | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.;39 Shibahashi et al.;51 Nordström et al49 |

| Dementia | Malec et al.;25 Henninger et al.;39 Seno et al50 |

| Postraumatic cerebral infarction | Marino et al.;47 Latronico et al.42 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | Barnes et al35 |

| Severe leukoaraiosis | Henninger et al.39 |

| Seizure | Yue et al.55 |

| Brain injury/disease | Lenell et al.43 |

| History of traumatic brain injury | Lenell et al.43 |

| Spinal cord injury | Mollayeva et al.48 |

| Movement disorder | Malec et al.25 |

| Sleep disorder | Malec et al.25 |

| Comorbidity Indices & Clusters | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | Utomo et al.;54 Maiden et al.46 |

| Elixhauser Score Index | Thompson et al.53 |

| Cumulative Illness Rating Scale | Humphries et al.40 |

| Comorbidity clusters (3) | Kumar et al.41 |

| Health status factors preceding injury (43) | chan et al.36 |

| Clinical signs | |

| Hypotension | Lingsma et al.;45 Henninger et al.;39 Maiden et al.;46 Latronico et al.42 |

| Hypoxia | Lingsma et al.;45 Henninger et al.;39 Latronico et al.42 |

| Systolic blood pressure | Henninger et al.;39 Nordström et al.49 utomo et al.54 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | Henninger et al.39 |

| High blood cholesterol | Malec et al.25 |

| Headache/migraine | Yue et al.55 |

| Vasospasm | Lin et al.44 |

Comorbidity indices and clusters

Charlson Comorbidity Index score was associated with independent living six-months post injury (GOS-E score≥5), in univariate logistic regression analyses.46, 54 A significant association was not shown in multivariate logistic regression analyses.46, 54 However, both studies demonstrated a negative association with older age groups and independent living, in multivariate analyses.46, 54 Thirty-four comorbid disorders listed in the ESI explained less than one percent of the total variance in mFIM total score at discharge.53 In contrast, medical comorbidity according to CIRS was shown to be associated with worse GOS-E scores at 12-months postinjury (OR, 1.34; 95%CI, 1.01–1.78; P=0.041).40

Comorbidity clusters (i.e., cluster one-acute hospital complications, cluster two-chronic disease, cluster three-substance abuse) demonstrated no significant association with one-year GOS-E scores.41 Although, cluster one weight was shown to be negatively associated with FIM efficiency and cluster three weight was shown to be positively associated with FIM efficiency.41 Further, higher cluster two weights was associated with older age, whereas higher cluster three weight was associated with younger age and being male.41 Ten factors of preinjury health status were shown to be significantly associated with reduced RFG in FIM for male patients, i.e., 1) Alzheimer disease and dementia (ß, −0.168; 95%CI, −0.315, −0.02; P<0.001); 2) epilepsy, seizures, brain lesions, and other (ß, −0.081; 95%CI, −0.154, −0.008; P<0.001); 3) pulmonary, abdominal, and other emergency (ß, −0.077; 95%CI, −0.119, −0.035; P<0.001); 4) stroke and emergencies involving the brain (ß, −0.057; 95%CI, −0.095, −0.019; P<0.001); 5) chronic cardiovascular pathology (ß, −0.057; 95%CI, −0.102, −0.012; P<0.001); 6) mental health disorders (ß, −0.053; 95%CI, −0.104, −0.002; P=0.001); 7) disorders of elderly and medical issues (ß, −0.051; 95%CI, −0.084, −0.018; P<0.001); 8) conditions and symptoms of abdomen and pelvis (ß, −0.044; 95%CI, −0.087, −0.002; P=0.001); 9) metabolic disorders and abdominal symptoms (ß, −0.035; 95%CI, −0.067, −0.002; P=0.001); and 10) cardiovascular disorders and others (ß, −0.034; 95%CI, −0.067, 0; P=0.001), whereas one factor was associated with reduced RFG for female patients, i.e., disorders of elderly and medical issues (ß, −0.047; 95%CI, −0.086, −0.009; P<0.001).36

Systemic medical diseases and other

Inconsistent findings regarding association between DM and functional outcomes were observed in univariate analyses, in which DM was associated with poor three-months mRS39 but not with six-months GOS,51 three-months GOS,39 discharge GOS,50 GOS-E (average 7.8 months),43 nor 12-months mRS.39 A significant association between DM and a poor three-month mRS score was consistently demonstrated in a multivariate analysis (OR, 6.5; 95%CI, 1.8–24.0; P=0.005).39 Motor and cognitive FIM trajectories were also negatively affected by DM over time.25 Consistently, DM was associated with lower FIM motor scores (t=−2.62, P=0.009) in a separate study.38 Sex/gender did not reach the level of statistical significance for mRS,39 GOS,39, 51 GOS-E,49 and FIM motor and cognitive outcomes.25 However, in one study the female sex was negatively associated with the trajectory of motor recovery.38

Hypertension was shown to negatively impact FIM motor (t=−4.11, P<0.001) and cognitive scores (t=−2.51, P=0.012) in a multivariate regression analysis, however the negative effect on motor recovery diminished over time.38 Similarly, in another study HPT negatively affected cognitive and motor functioning trajectories.25 In contrast, in univariate analyses HPT was not associated with three and 12-months mRS,39 three- and six-months GOS,39, 51 nor GOS scores at discharge.50 Likewise, in a multivariate logistic regression analysis, HPT/CV was not associated with GOS-E scores at different time points.43, 55 Cardiac conditions were negatively associated with motor recovery and a more rapid rate of cognitive recovery.38 However in a separate study, cardiac-structural/ischemic/valvular conditions were not predictors of worse outcome (GOS-E≤6) at three-nor six-months postinjury.55 Respiratory conditions were not associated with FIM motor nor cognitive scores.38 Similarly pulmonary conditions were not associated with three- nor six-months GOS-E scores.55 In contrast, chronic bronchitis was shown to negatively impact cognitive functioning.25 Gastrointestinal conditions were not predictive of three- nor six-months GOS-E scores.55

Conflicting findings regarding the association between cancer and functional outcome were reported. In univariate analyses, no significant association was observed between cancer and three and 12-months mRS39 and three- and six-months GOS.39, 51 However, in a stepwise backward elimination multivariate logistic regression analysis, cancer (i.e., esophageal, gastric, duodenal, colorectal, liver, breast, prostatic, bladder carcinoma) was associated with GOS scores at discharge in older adults (≥75 years old) (OR, 14.005; 95%CI, 1.262–154.444; P=0.032).50 Similarly, cancer, other than skin cancer, negatively affected the FIM motor and cognitive outcome trajectories.25

Osteoporosis index severity, assessed via the Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool for Asians (OSTA), was demonstrated to be associated with poor outcome (OR, 1.157; 95%CI, 1.057–1.266; P=0.002), adjusted for age, sex/gender, body weight, injury severity, and avoidance of neurosurgery.37 A significant association remained when results were stratified by age (≥40 years). Rheumatoid arthritis was reported to negatively impact the trajectory of motor functioning over time.25 A significant association was not observed for cognitive functioning.25 Similarly, in a multivariable regression analysis, sarcopenia, determined by skeletal muscle mass, was significantly associated with a poor GOS score (OR, 3.88; 95% CI 1.14–13.20, P=0.031) and further demonstrated an association when stratified by age (<75 years).51 Sex/gender did not reach the level of statistical significance in univariate analyses for GOS scores.37, 51

Neurological and nervous system disorders

The presence of PTCI was associated with decreased GOS six-months post-trauma (OR of good outcome, 0.19; 95%CI, 0.06–0.66; p-value NR).47 This association was shown in a separate population comparable in age, sex/gender, severity of brain trauma, and time spent in intensive care unit. Consistently in a separate study, PTCI was an independent predictor of an unfavorable six-months outcome (GOS≤3) (OR, 4.77; 95%CI, 2.19–10.67; P<0.001).54An association between leukoaraiosis severity and a poor three-months mRS score was also observed in patients of all injury severities (OR, 2.5; 95%CI, 1.7–3.6; P<0.001), in a multivariable logistic regression analysis.39 Significance was also shown for three-months GOS and 12-months mRS and GOS.39 Further, findings in a univariate analysis showed pre-existing dementia to be associated with a poor mRS at three-months.39 Findings in a stepwise backward elimination multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated dementia, to be associated with poor GOS at discharge (OR, 20.357; 95%CI, 2.075–199.683; P=0.010).50 In another study, the presence of comorbid SCI was associated with the risk of developing dementia (HR, 1.08; 95%CI, 1.03–1.12; P<0.001), particularly in males (HR, 1.13; 95%CI, 1.06–1.21; P<0.001), but not in females (HR, 1.05; 95%CI, 1.00–1.12; P=0.079), controlling for other known risks of dementia.48 Similarly, one study demonstrated an independent additive association with CVD on the risk of developing dementia.35 However, three studies investigating stroke demonstrated no association with young onset dementia (YOD) in a logistic regression analysis49 and poor mRS39 and GOS score51 in a univariate analysis. Previous brain injury/disease and history of TBI were also not associated with poor GOS-E scores.43

Clinical signs

History of headache/migraine were demonstrated to be associated with a worse outcome at three-months postinjury (GOS-E≤6; OR, 4.10; 95%CI, 1.67–10.07; P=0.002).55 Hypotension, SBP and DBP at hospital admission, and hypoxia were not associated with poor three-months mRS and GOS scores and 12-months mRS scores in a univariate analysis.39 A study similarly reported no association between SBP and YOD.49 Further, studies demonstrated no association between hypoxia42, 45 nor hypotension42, 45, 46 and disability. Though, one study showed patients with a SBP of 131–150 mmHg at admission to have more than a three-fold increase in odds of living independently (GOS-E score ≥ 5) compared to patients with a SBP less than 131 mmHg (OR, 3.49; 95%CI, 1.30–9.35; P=0.013), in a multivariate backward stepwise logistic regression analysis.54 One study that examined vasospasm and GOS at six-months following a traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage (tSAH), showed that the difference in adverse effect among patients with vasospasm compared to those without was not statistically significant (OR, 5.04; 95%CI, 0.83–30.85; P=0.080), accounting for age, sex/gender, severity of head injury, and tSAH subgroups.44

Psychiatric and psychological disorders

Alcohol use was significantly associated with a poor mRS and GOS at three-months in a univariate analysis, mean-while illicit drug use was only associated with a poor mRS at 12-months.39 In another study, alcohol and drug use was positively associated with FIM motor scores.38 Further, alcohol intoxication was a predictor of worse GOS-E at 12-months in a multi-ordinal regression analysis (OR, 1.84; 95%CI, 1.40–2.42; P<0.001).40 In contrast, alcohol intoxication was not associated with three- nor six-months GOS in a univariate analysis of a separate study.45 Similarly, preinjury alcohol use was not associated with GOS-E outcome scores in both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses.43 Further, one study demonstrated that there was no association between preinjury alcohol use and postinjury cognitive functioning in a multiple regression analysis, which involved attention and concentration, verbal and nonverbal, immediate and delayed memory, expressive language, visuospatial abilities, abstract reasoning, and judgement.52 Alcohol and drug intoxication did not show any significant associations with YOD as well.49

One study demonstrated an independent additive association with depression or PTSD on the risk of developing dementia.35 Similarly, one study showed an association between depression and YOD in patients with more than one mild TBIs.49 Furthermore, depression was greatly associated with diminished cognitive functioning over time25 and decreased motor recovery.38 Studies demonstrated a strong association between history of psychiatric conditions and a lower three-month (OR, 2.2; 95%CI, 1.4–3.2; P<0.001)45 (GOS-E≤6; OR, 2.75; 95%CI, 1.44–5.27; P=0.002),55 six-month (OR, 2.4; 95%CI, 1.6–3.7; P<0.001)45 (GOS-E≤6; OR, 2.57; 95%CI, 1.38–4.77; P=0.003),55 and 12-month GOS-E (OR, 2.80; 95%CI, 2.12–3.71; P<0.001)40 among patients with TBI. Of the two studies that examined the association between anxiety and FIM motor and cognitive scores, one study reported significant findings25 while the other did not (Table II).25, 35–55

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized scientific evidence of the relationship between comorbidity and functional outcomes, in the light of age, sex/gender, and injury severity, with the goal of obtaining a set of comorbidities that impact the recovery trajectory of patients with TBI. In summary, all but five of the 22 included studies showed that comorbidity associates with worse functional outcomes; however, the strength of association and predictive effects, even within the same category of comorbidity, differed from study to study. This was not unexpected given the heterogeneity observed in clinical characteristics, types of comorbidities, measures of functional outcomes, timing of assessments, and statistical approaches to study associations. Therefore, careful consideration of comorbidity in patients with TBI is critical in clinical settings, to account for their influence on injury recovery and postinjury functioning.

Relationship of comorbidity and outcome

COMORBIDITY INDICES AND CLUSTERS

Comorbidity measured by the CCI was shown not to be associated with functional outcomes.46, 54 In another study, comorbidity measured by the ESI, explained less than one percent of the total variance in mFIM at discharge, while adjusting for age, sex/gender and injury severity (i.e., ISS and GCS).53 This limited association between number of comorbidities and functional outcome might be related to the low sensitivity and specificity of ESI as reported by researchers who utilized this tool.53 Further the CCI and ESI were not developed for the TBI population,65, 66 and as such before its application to a TBI sample, researchers have to ensure that these tools measure what they are intended to measure (i.e., construct validity) and are sensitive to change in the population of interest (i.e., reliability properties).67 Conversely, medical comorbidity per CIRS was demonstrated to be associated with worse functional outcome.40 While it is essential to investigate the impact of individual comorbidities on functional outcome, it is equally imperative to capture the cumulative burden of comorbidities on long-term outcome post-TBI. Future studies are needed to assess whether these indices are accurate measurements of comorbidity in TBI, and in assessing the intersection between comorbidity, recovery-related factors (i.e., age, sex/gender, injury severity) and measurements of functional outcome.

Comorbidity clusters, including acute hospital complications, chronic disease, and substance abuse clusters were shown to have inconsistent associations with global functioning across outcome measurements.41 A separate study investigated 43 factors of preinjury health status, while considering associations with RFG in inpatient rehabilitation, specific to each sex. A total of ten factors were shown to be significantly associated with reduced RFG in males, in comparison to one factor in females.36 Attention to categorization of comorbid health conditions and stratification by sex, can help to understand the influence of comorbidity on functional outcome and inform sex-specific clinical intervention within rehabilitation sectors.

SYSTEMIC MEDICAL DISEASES AND OTHER

Inconsistent findings were reported among the seven studies that examined DM in association with functional outcome, with three studies reporting a significant association with poor outcome including, lower three-months mRS scores39 and FIM motor25, 38 and cognitive scores over time.25 This suggests that potential insulin deficiency in TBI patients with DM, may require close monitoring and more aggressive care to improve functional outcome. Similarly, findings were mixed among studies examining HPT and/or CV/cardiac conditions and functional outcome. Hypertension25, 38 and cardiac conditions38 were shown to significantly impact FIM motor and cognitive recovery. Though hypertension negatively impacted both motor and cognitive recovery,25, 38 cardiac conditions were significantly associated with a more rapid rate of cognitive recovery at five years postinjury.38 This finding is inconsistent with previous literature that points to an association between cardiac disease and cognitive impairment or dementia.68

Among studies that examined cancer,25, 39, 50, 51 two studies observed a significant association with poor functional outcome, specifically lower GOS scores at discharge in older adults,50 and a decline in FIM motor and cognitive outcome trajectories over a ten-year period.25 Further investigation regarding the impact of cancer, while considering intersecting vulnerabilities of age and immune status is required.

Since osteoporosis can indicate physical deterioration, the condition was examined in association with functional outcome, measured by GOS at hospital discharge.37 The study demonstrated that a higher OSTA index was associated with a better outcome while controlling for age, sex/gender, and injury severity (i.e., GCS, ISS, NISS, AIS for head).37 An association was also observed when stratified by age (i.e., ≥40 years group only).37 Rheumatoid arthritis was also reported to negatively impact motor functioning over time.25 Similarly, sarcopenia was observed to be associated with poor outcome, measured by GOS at six-months, when controlling for age, sex/gender, and GCS motor score.51 The study also examined the relative risk of poor outcome in association with sarcopenia, in a stratified analysis by age (<75 vs. ≥75 years) and observed an association (not significant for the ≥75 years age group).51 Further, analyses demonstrated that skeletal muscle area was significantly larger in males than in females, although an analysis involving functional outcome was not conducted.51 These findings indicate that reduced muscle mass may be an integral factor in recovery for older persons and females with TBI. The results additionally reveal the need to consider not only the individual impact of musculoskeletal disorders on TBI recovery in treatment plans, but also their synergistic effects, while considering sex/gender and age of patients with TBI.

NEUROLOGICAL AND NERVOUS SYSTEM DISORDERS

Several neurological disorders were shown to affect functional outcome. Posttraumatic cerebral infarction demonstrated to be an independent predictor of GOS score,42, 47 which is consistent with previous study.69 However, it would be difficult to know whether the disability was caused by the posttraumatic cerebral infarction episode, the primary brain damage from the TBI, or from other non-ischemic complications.47 Likewise, cerebral vasospasm was demonstrated to increase the rate of poor functional outcome to 47.4% compared to 24.7%, despite a lack of statistical significance.44

Severe leukoaraiosis has demonstrated to predict both a poor short-term (three-months mRS and GOS) and long-term functional outcome (12-months mRS and GOS).39 When age was included in the leukoaraiosis model of three-months mRS, the observed association did not change; however, removing leukoaraiosis from the age model demonstrated significance with three-months mRS. This finding underscores the idea that leukoaraiosis is a marker of biological age (i.e., person’s physical and mental function) as opposed to chronological age when predicting outcome.39 Further, stratification by injury severity (i.e., GCS≤12, GCS=13–15) showed a significant association between leukoaraiosis severity and poor three-months mRS for both severity categorization.39 However, the research design may have yielded results that are not representative of the entire TBI population, as participants with more severe acute brain pathology were excluded to allow reliable leukoaraiosis grading.39

Among the studies that examined the effect of stroke on outcome post-TBI,25, 39, 49, 51 three studies39, 49, 51 observed a lack of association with global functioning. These findings are in contrast with previous literature, in which concurrent ischemic stroke was predictive of worse functional outcome (i.e., motor and cognitive FIM scores).70 However, one study demonstrated an increased dementia risk in veterans with TBI and CVD.35 Additionally, comorbid SCI was shown to be significantly associated with dementia incidence in male patients specifically, and the hazard ratio was age-dependant.48 Dementia as a comorbid disorder was also reported to be associated with poor outcome.50 Therefore, it appears that various neurological disorders and related precursors have the potential to impact cognitive and physical functioning following TBI.

CLINICAL SIGNS

The most frequent clinical signs and symptoms that were studied were SBP, hypotension, and hypoxia. SBP on hospital arrival was shown to be associated with independent living (GOS-E score≥5), for patients with moderate to severe TBI.54 This finding alludes to the impact of secondary systemic insults (i.e., low SBP) on functionality following TBI.54 There is also evidence that hypotension and hypoxia are not associated with functional outcome.39, 42, 45, 46 The discrepancy between studies may be attributed to the severity and reversibility of the secondary systemic insults, where a shorter duration or a less severe secondary systemic event can have a decreased effect on functioning.71 Overall, there is a need for early attention to comorbidity in preventing additional disability within the pathological process of brain injury, as well as in its association with functional capacity.72, 73

PSYCHIATRIC AND PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

In the literature, there is mixed evidence that alcohol use does74, 75 and does not impact functional outcome in patients with TBI.76–78 A recent systematic review demonstrated that preinjury substance use predicts disability, with disability defined using measurements that describe activity limitations or participation restrictions, and included community integration, employment status, and life satisfaction.78 An association between alcohol use and disability was observed among two studies in the current systematic review, with one reporting on a positive association between alcohol and drug use and FIM motor functioning38 and another reporting on alcohol intoxication and poor global functioning at 12-months postinjury.40 In a separate study preinjury alcohol use was not associated with global functionig.43 Both alcohol and drug intoxication failed to contribute to YOD.49 Further, a strong association between TBI severity and YOD was greatly reduced by controlling for alcohol abuse and age,49 suggesting that these covariates may largely contribute to YOD than injury severity does. In a second study, alcohol use variables were also not associated with postinjury cognitive functioning.52 Alcohol use variables were mainly self-reported, which can be obscured by social desirability or recall biases.52 The time of cognitive assessment was not equivalent across patients and consequently may affect score reliability as well. Further, the cognitive measurements utilized may not be sensitive enough to capture the impact of preinjury alcohol use soon after TBI. The long-term impact of pre- and postinjury alcohol use on recovery may yield different results. More research on alcohol use and functional outcome is required, while taking into consideration chronic alcohol use and its cumulative effect, as well as alcohol intoxication at the time of injury.

Three of the 22 studies sought to examine the association between TBI and dementia, while considering dementia related-health concerns (e.g., CVD, depression). For those three studies, we considered dementia as a functional outcome given its diagnosis was reported using ICD codes - specific cognitive criteria would have needed to be met to make the diagnosis.79 Depression and PTSD have been frequently studied in relation to TBI and cognitive recovery. One study has demonstrated that both depression and PTSD in patients with TBI increase the risk of dementia.35 Additionally, depression and anxiety were shown to be associated with a decline in cognitive functioning over time.25 In contrast, a study has found the opposite effect between depression and YOD for individuals with a history of one TBI.49 In terms of global functioning, depression, anxiety, and psychiatric history were all shown to be associated with poor outcome.25, 38, 40, 45, 55 Therefore, relations between mental health and functional outcomes post-TBI requires further scrutiny, as it can be difficult to differentiate between mental illness and the manifestation of brain injury at the time of admission and follow-up.

INTERSECTING VARIABLES

Previous studies have demonstrated findings regarding the effects of age, sex/gender, and TBI severity and outcomes.80–83 When we investigated their associations with functional outcomes, the results were inconsistent: several studies confirmed an association between older age and poor functioning;25, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42–46, 48, 51, 54 while other studies demonstrated a lack of an association.38, 47, 50, 52, 53, 55 Further, the majority of studies that examined the influence of sex/gender on functional outcome did not find a statistically significant association;25, 37, 39, 40, 43–46, 50–53, 55 however many of the included studies predominately consisted of male participants (i.e., 60 to 100%).25, 35–45, 47, 49, 51–55 The majority of studies demonstrated that TBI severity is associated with functional outcome.37, 38, 40, 42, 44, 45, 48, 53, 54

Despite potential association with outcome, age, sex and gender, and TBI severity were rarely studied in relation to comorbidity. Only three studies stratified their results by age or used an interaction of comorbidity with age when reporting results;37, 48, 51 one study stratified their results by injury severity;39 and two studies stratified their results by sex/gender.36, 48 Further, studies only considered binary sex/gender constructs in their analyses and although gender may have been reported to be studied, it appeared studies were examining sex. Sex and gender and age considerations are crucial as some of the most prevalent conditions observed in TBI (e.g., depression, HPT, DM, SCI) have a recognized sex and gender and age difference that can uniquely impact physical and cognitive functioning.22, 48, 84, 85 In addition, TBI severity has been shown to be associated with the onset of comorbid conditions.86 Therefore, considering age, sex and gender, and injury severity may detect an influence on the relationship between comorbidities and functional outcomes.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

The purpose of this evidence synthesis was to recapitulate the range of comorbidities in patients with TBI and their associations to functional outcomes, in order to inform clinicians working with patients with TBI. The results emphasize that TBI, as an acute injury and a chronic disorder, is almost always associated with worse function in the presence of comorbidity. It follows that addressing TBI related impairments requires reversing (or substantially improving) the specific dysfunctions associated with comorbidity, and that a thorough knowledge of patients’ comorbidity is key to expedite recovery and address dysfunction associated with TBI. The clinical implications are that analyzing all of the elements of the patient’s clinical history requires analytical thinking and willingness on the part of clinicians to reflect deeply not only on the physiological changes brought on by the TBI event, but also on the physiological and psychological imbalances that are associated with age, sex and gender, and comorbidity in affecting patients’ ability to function after the injury.

Limitations of the study

This systematic review has several limitations. First, included studies’ heterogeneity at multiple levels (i.e., sample characteristics, clinical settings, spectrum of studied comorbidities, selective reporting, different statistical approaches, and outcome measurements) did not generate the precision and the confidence we had expected when we initiated this review; the strength of association of even the same type of comorbidity varied across individual studies. As such, direct application of these studies’ results to patient care may be problematic. Second, most studies focused on comorbid disorders while considering multiple controlling variables, with varying attenuation effects on the association between comorbidity and functional outcomes. This may have introduced a bias when we attempted to perform direct comparisons. Third, the strength and significance of associations of factors aside from age, sex/gender, and TBI severity (e.g., glucose level, craniotomy/craniectomy, extracranial injury) were not examined in the literature included in this review, and therefore the roles of these factors, frequently collected in clinical settings, could be underestimated. Further, a possibility exists that the associations between comorbidity and the outcomes of interest can be attenuated due to “overcontrolled” models included in this review (Supplementary Digital Material 3: Supplementary Table IV). For instance, since there is a possible causal relationship between number of comorbidity and age, including age in a model might have attenuated the association between number of comorbidity and functional outcome because age is in the causal pathway. Similarly, including hypoxia in a model of cognitive outcomes that included injury severity, could attenuate the relationship between hypoxia and cognitive outcome. Another limitation is that the focus of this review was the association between comorbidity and physical and/or cognitive functioning across time continuum postinjury, and not the effect of treatment or adherence to treatment when reporting results. It is possible, therefore, that participants whose comorbidities were treated demonstrated beneficial functional outcomes compared to those who were not. Further, publication bias was not formally assessed as there were limited number of studies that passed the quality criteria. Finally, we eliminated non-English language articles, which can affect generalizability of our results.

Conclusions

The results of this systematic review support the view of TBI as a disorder with multiple comorbidities, each of which has the potential to influence recovery and outcomes. Further research on comorbidity and its onset in relation to a TBI event is warranted, to advance precision in patients’ care and rehabilitation, and prevent functional disabilities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

The authors acknowledge Jessica Babineau, information specialist at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute-University Health Network for her valuable help with the literature search.

Funding.

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R21HD089106 and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01NS117921. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Angela Colantonio was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Chair in Gender, Work and Health [Grant no. CGW-126580]. Tatyana Mollayeva was supported by the Alzheimer’s Association Grant [AARF-16-442937]. Sara Hanafy was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Institute of Gender and Health research grant [#CGW-126580], the University of Toronto Fellowship, and the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute Student Scholarship. This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs Program.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest.—The authors certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Supplementary data.—For supplementary materials, please see the HTML version of this article at www.minervamedica.it

References

- 1.Injury AB. About brain injury. Brain Injury Association of America; 2017. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.biausa.org/brain-injury/about-brain-injury [cited 2021, Feb 22]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarvonen-Schröder S, Tenovuo O, Kaljonen A, Laimi K. Comparing disability between traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury using the 12-item WHODAS 2.0 and the WHO minimal generic data set covering functioning and health. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:1676–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maas AI, Menon DK, Adelson PD, Andelic N, Bell MJ, Belli A, et al. ; InTBIR Participants and Investigators. Traumatic brain injury: integrated approaches to improve prevention, clinical care, and research. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:987–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones DS, Quinn S. Textbook of Functional Medicine. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salottolo K, Levy AS, Slone DS, Mains CW, Bar-Or D. The effect of age on Glasgow Coma Scale score in patients with traumatic brain injury. JAMA Surg 2014;149:727–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Avesani R, Fedeli M, Ferraro C, Khansefid M. Use of early indicators in rehabilitation process to predict functional outcomes in subjects with acquired brain injury. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2011;47:203–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chelly H, Bahloul M, Ammar R, Dhouib A, Mahfoudh KB, Boudawara MZ, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of traumatic head injury following road traffic accidents admitted in ICU “analysis of 694 cases”. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2019;45:245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawley C, Sakr M, Scapinello S, Salvo J, Wrenn P. Traumatic brain injuries in older adults-6 years of data for one UK trauma centre: retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Emerg Med J 2017;34:509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanitanon A, Lyons VH, Lele AV, Krishnamoorthy V, Chaikittisilpa N, Chandee T, et al. Clinical Epidemiology of Adults With Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care Med 2018;46:781–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dams-O’Connor K, Ketchum JM, Cuthbert JP, Corrigan JD, Hammond FM, Haarbauer-Krupa J, et al. Functional Outcome Trajectories Following Inpatient Rehabilitation for TBI in the United States: A NIDILRR TBIMS and CDC Interagency Collaboration. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2020;35:127–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munivenkatappa A, Agrawal A, Shukla DP, Kumaraswamy D, Devi BI. Traumatic brain injury: does gender influence outcomes? Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2016;6:70–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arellano-Orden V, Leal-Noval SR, Cayuela A, Muñoz-Gómez M, Ferrándiz-Millón C, García-Alfaro C, et al. Gender influences cerebral oxygenation after red blood cell transfusion in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care 2011;14:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollayeva T, Colantonio A. Gender, Sex and Traumatic Brain Injury: Transformative Science to Optimize Patient Outcomes. Healthc Q 2017;20:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan V, Mollayeva T, Ottenbacher KJ, Colantonio A. Sex-Specific Predictors of Inpatient Rehabilitation Outcomes After Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:772–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Science is better with sex and gender. Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2019. [Internet]. Available from: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/51310.html [cited 2021, Feb 22].

- 16.Mollayeva T, Mollayeva S, Colantonio A. Traumatic brain injury: sex, gender and intersecting vulnerabilities. Nat Rev Neurol 2018;14:711–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinstein AR. The pre-therapeutic classification of co-morbidity in chronic disease. J Chronic Dis 1970;23:455–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Masel BE, DeWitt DS. Traumatic brain injury: a disease process, not an event. J Neurotrauma 2010;27:1529–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brandel MG, Hirshman BR, McCutcheon BA, Tringale K, Carroll K, Richtand NM, et al. The Association between Psychiatric Comorbidities and Outcomes for Inpatients with Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neurotrauma 2017;34:1005–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu CL, Kor CT, Chiu PF, Tsai CC, Lian IB, Yang TH, et al. Long-term renal outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury: A nationwide population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0171999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mollayeva T, Sutton M, Chan V, Colantonio A, Jana S, Escobar M. Data mining to understand health status preceding traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep 2019;9:5574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond FM, Corrigan JD, Ketchum JM, Malec JF, Dams-O’Connor K, Hart T, et al. Prevalence of Medical and Psychiatric Comorbidities Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2019;34:E1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skandsen T, Ivar Lund T, Fredriksli O, Vik A. Global outcome, productivity and epilepsy 3–8 years after severe head injury. The impact of injury severity. Clin Rehabil 2008;22:653–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howrey BT, Graham JE, Pappadis MR, Granger CV, Ottenbacher KJ. Trajectories of Functional Change After Inpatient Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:1606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malec JF, Ketchum JM, Hammond FM, Corrigan JD, Dams-O’Connor K, Hart T, et al. Longitudinal Effects of Medical Comorbidities on Functional Outcome and Life Satisfaction After Traumatic Brain Injury: An Individual Growth Curve Analysis of NIDILRR Traumatic Brain Injury Model System Data. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2019;34:E24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bisson EJ, Fakolade A, Pétrin J, Lamarre J, Finlayson M. Exercise interventions in multiple sclerosis rehabilitation need better reporting on comorbidities: a systematic scoping review. Clin Rehabil 2017;31:1305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peltz CB, Gardner RC, Kenney K, Diaz-Arrastia R, Kramer JH, Yaffe K. Neurobehavioral Characteristics of Older Veterans With Remote Traumatic Brain Injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2017;32:E8–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mollayeva T, Xiong C, Hanafy S, Chan V, Hu ZJ, Sutton M, et al. Comorbidity and outcomes in traumatic brain injury: protocol for a systematic review on functional status and risk of death. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyer T, Wulff K. Issues of comorbidity in clinical guidelines and systematic reviews from a rehabilitation perspective. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2019;55:364–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Painter P, Stewart AL, Carey S. Physical functioning: definitions, measurement, and expectations. Adv Ren Replace Ther 1999;6:110–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cognitive function.(n.d). In: Mosby’s Medical Dictionary. 8th editio; 2009. [Internet]. Available from: https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/cognitive+function [cited 2021, Feb 22]. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 50: A guideline developers’ handbook. Edinburgh: SIGN Publ; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slavin RE. Best evidence synthesis: an intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barnes DE, Kaup A, Kirby KA, Byers AL, Diaz-Arrastia R, Yaffe K. Traumatic brain injury and risk of dementia in older veterans. Neurology 2014;83:312–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chan V, Sutton M, Mollayeva T, Escobar MD, Hurst M, Colantonio A. Data Mining to Understand How Health Status Preceding Traumatic Brain Injury Affects Functional Outcome: A Population-Based Sex-Stratified Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2020;101:1523–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao CH, Su YF, Chan HM, Huang SL, Lin CL, Kwan AL, et al. Osteoporosis Self-Assessment Tool for Asians Can Predict Neurologic Prognosis in Patients with Isolated Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corrigan JD, Zheng T, Pinto SM, Bogner J, Kean J, Niemeier JP, et al. Effect of Preexisting and Co-Occurring Comorbid Conditions on Recovery in the 5 Years After Rehabilitation for Traumatic Brain Injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2020;35:E288–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henninger N, Izzy S, Carandang R, Hall W, Muehlschlegel S. Severe leukoaraiosis portends a poor outcome after traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care 2014;21:483–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Humphries TJ, Ingram S, Sinha S, Lecky F, Dawson J, Singh R. The effect of socioeconomic deprivation on 12 month Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) outcome. Brain Inj 2020;34:343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumar RG, Olsen J, Juengst SB, Dams-O’Connor K, O’Neil-Pirozzi TM, Hammond FM, et al. Comorbid Conditions Among Adults 50 Years and Older With Traumatic Brain Injury: Examining Associations With Demographics, Healthcare Utilization, Institutionalization, and 1-Year Outcomes. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2019;34:224–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Latronico N, Piva S, Fagoni N, Pinelli L, Frigerio M, Tintori D, et al. Impact of a posttraumatic cerebral infarction on outcome in patients with TBI: the Italian multicenter cohort INCEPT study. Crit Care 2020;24:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lenell S, Nyholm L, Lewén A, Enblad P. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in elderly traumatic brain injury patients receiving neurointensive care. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2019;161:1243–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin TK, Tsai HC, Hsieh TC. The impact of traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage on outcome: a study with grouping of traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage and transcranial Doppler sonography. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;73:131–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lingsma HF, Yue JK, Maas AI, Steyerberg EW, Manley GT; TRACK-TBI Investigators. Outcome prediction after mild and complicated mild traumatic brain injury: external validation of existing models and identification of new predictors using the TRACK-TBI pilot study. J Neurotrauma 2015;32:83–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maiden MJ, Cameron PA, Rosenfeld JV, Cooper DJ, McLellan S, Gabbe BJ. Long-Term Outcomes after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Older Adults. A Registry-based Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;201:167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marino R, Gasparotti R, Pinelli L, Manzoni D, Gritti P, Mardighian D, et al. Posttraumatic cerebral infarction in patients with moderate or severe head trauma. Neurology 2006;67:1165–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mollayeva T, Hurst M, Escobar M, Colantonio A. Sex-specific incident dementia in patients with central nervous system trauma. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2019;11:355–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nordström P, Michaëlsson K, Gustafson Y, Nordström A. Traumatic brain injury and young onset dementia: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Neurol 2014;75:374–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seno S, Tomura S, Ono K, Tanaka Y, Ikeuchi H, Saitoh D. Poor prognostic factors in elderly patients aged 75 years old or older with mild traumatic brain injury. J Clin Neurosci 2019;67:124–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shibahashi K, Sugiyama K, Hoda H, Hamabe Y. Skeletal Muscle as a Factor Contributing to Better Stratification of Older Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury: A Retrospective Cohort Study. World Neurosurg 2017;106:589–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner AP, Kivlahan DR, Rimmele CT, Bombardier CH. Does pre-injury alcohol use or blood alcohol level influence cognitive functioning after traumatic brain injury? Rehabil Psychol 2006;51:78–86. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson HJ, Dikmen S, Temkin N. Prevalence of comorbidity and its association with traumatic brain injury and outcomes in older adults. Res Gerontol Nurs 2012;5:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Utomo WK, Gabbe BJ, Simpson PM, Cameron PA. Predictors of in-hospital mortality and 6-month functional outcomes in older adults after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Injury 2009;40:973–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yue JK, Cnossen MC, Winkler EA, Deng H, Phelps RR, Coss NA, et al. ; TRACK-TBI Investigators. Pre-injury Comorbidities Are Associated With Functional Impairment and Post-concussive Symptoms at 3- and 6-Months After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: A TRACK-TBI Study. Front Neurol 2019;10:343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCulloch KL, de Joya AL, Hays K, Donnelly E, Johnson TK, Nirider CD, et al. Outcome Measures for Persons With Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Recommendations From the American Physical Therapy Association Academy of Neurologic Physical Therapy TBI EDGE Task Force. J Neurol Phys Ther 2016;40:269–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jennett B, Bond M. Assessment of outcome after severe brain damage. Lancet 1975;1:480–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson JT, Pettigrew LE, Teasdale GM. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: guidelines for their use. J Neurotrauma 1998;15:573–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rankin J. Cerebral vascular accidents in patients over the age of 60. II. Prognosis. Scott Med J 1957;2:200–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farrell B, Godwin J, Richards S, Warlow C. The United Kingdom transient ischaemic attack (UK-TIA) aspirin trial: final results. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1991;54:1044–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Keith RA, Zielezny M, Sherwin FS. Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Top Geriatr Rehabil 1986;1:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keith RA, Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Sherwin FS. The functional independence measure: a new tool for rehabilitation. Adv Clin Rehabil 1987;1:6–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mosenthal AC, Livingston DH, Lavery RF, Knudson MM, Lee S, Morabito D, et al. The effect of age on functional outcome in mild traumatic brain injury: 6-month report of a prospective multicenter trial. J Trauma 2004;56:1042–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:917–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 1998;36:8–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.New PW, Earnest A, Scroggie GD. A comparison of two comorbidity indices for predicting inpatient rehabilitation outcomes. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2017;53:493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Deckers K, Schievink SH, Rodriquez MM, van Oostenbrugge RJ, van Boxtel MP, Verhey FR, et al. Coronary heart disease and risk for cognitive impairment or dementia: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu S, Wan X, Wang S, Huang L, Zhu M, Zhang S, et al. Post-traumatic cerebral infarction in severe traumatic brain injury: characteristics, risk factors and potential mechanisms. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2015;157:1697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kowalski RG, Haarbauer-Krupa JK, Bell JM, Corrigan JD, Hammond FM, Torbey MT, et al. Acute Ischemic Stroke After Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: Incidence and Impact on Outcome. Stroke 2017;48:1802–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Volpi PC, Robba C, Rota M, Vargiolu A, Citerio G. Trajectories of early secondary insults correlate to outcomes of traumatic brain injury: results from a large, single centre, observational study. BMC Emerg Med 2018;18:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Scarponi F, Zampolini M, Zucchella C, Bargellesi S, Fassio C, Pistoia F, et al. ; C.I.R.C.LE (Comorbidità in Ingresso in Riabilitazione nei pazienti con grave CerebroLEsione acquisita) study group. Identifying clinical complexity in patients affected by severe acquired brain injury in neurorehabilitation: a cross sectional survey. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2019;55:191–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Intiso D, Fontana A, Maruzzi G, Tolfa M, Copetti M, DI Rienzo F. Readmission to the acute care unit and functional outcomes in patients with severe brain injury during rehabilitation. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2017;53:268–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hammond FM, Baker-Sparr CA, Dahdah MN, Dams-O’Connor K, Dreer LE, O’Neil-Pirozzi TM, et al. Predictors of 1-Year Global Outcomes After Traumatic Brain Injury Among Older Adults: A NIDILRR Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems Study. J Aging Health 2019;31:68S–96S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van der Naalt J, Timmerman ME, de Koning ME, van der Horn HJ, Scheenen ME, Jacobs B, et al. Early predictors of outcome after mild traumatic brain injury (UPFRONT): an observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:532–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vickery CD, Sherer M, Nick TG, Nakase-Richardson R, Corrigan JD, Hammond F, et al. Relationships among premorbid alcohol use, acute intoxication, and early functional status after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Silverberg ND, Panenka W, Iverson GL, Brubacher JR, Shewchuk JR, Heran MK, et al. Alcohol Consumption Does not Impede Recovery from Mild to Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2016;22:816–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]