Abstract

Background

The prognosis of miliary pulmonary metastases (MPM), which are characterized as randomly disseminated, innumerable, and small metastatic nodules, has been considered as being poor. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the clinical characteristics and survival of MPM in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

This retrospective study included NSCLC patients with MPM and nonmiliary pulmonary metastases (NMPM) detected during staging evaluation between 2000 and 2020. MPM was defined as >50 bilaterally distributed metastatic pulmonary nodules (<1 cm in diameter), and NMPM was defined as the presence of ≤15 metastatic pulmonary nodules regardless of size. Baseline characteristics, genetic alterations and overall survival (OS) rates were compared between the two groups.

Results

Twenty‐six patients with MPM and 78 patients with NMPM were analyzed. The median number of patients who smoked was significantly lower in the MPM group than in the NMPM group (0 vs. 8 pack years, p = 0.030). The frequency of EGFR mutation was significantly higher in the MPM group (58%) than in the NMPM group (24%; p = 0.006). There was no significant difference in 5‐year OS between the MPM and the NMPM group by the log‐rank test (p = 0.900).

Conclusion

MPM in NSCLC were significantly related to EGFR mutation. The OS rate of the MPM group was not inferior to that of the NMPM group. The presence of EGFR mutations should be thoroughly evaluated for NSCLC patients with initial presentation of MPM.

Keywords: EGFR mutation, miliary pulmonary metastases, non‐small cell lung cancer, overall survival

This retrospective study compared the clinical characteristics and survival outcomes of NSCLC patients with miliary pulmonary metastases (MPM) and nonmiliary pulmonary metastases (NMPM). The MPM group had a lower median amount of patients who smoked and a higher frequency of EGFR mutation compared to the NMPM group. However, there was no significant difference in the 5‐year overall survival between the two groups. These findings suggest the importance of thoroughly evaluating EGFR mutation in NSCLC patients with initial presentation of MPM.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is a significant global public health issue that accounts for about one in five of all cancer deaths. 1 Non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80%–85% of all lung cancers and its prevalence has increased steadily. 2 In the eighth edition of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) staging of NSCLC, tumor nodule(s) in ipsilateral lobes other than that of the primary tumor, and tumor nodule(s) in a contralateral lobe, are classified as T4 and M1a, respectively. 3 , 4 The median survival of patients with contralateral or bilateral pulmonary metastases is 12 months. 5 Unfortunately, the only treatment option for patients with disseminated pulmonary metastases is palliative chemotherapy.

Among various genetic alterations, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene mutation, anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene rearrangement, and Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) gene mutation are the most frequently detected in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. 6 Agents that target the EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement, such as EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and ALK‐TKIs, improve the response and progression‐free survival rates of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. 7 Interestingly, several studies have reported an unusual form of lung cancer metastasis, which presents as numerous tiny nodules distributed diffusely throughout both lung fields, similar in appearance to miliary tuberculosis and particularly appearing in NSCLC patients. 8 , 9 This form of metastases is associated with female gender and no smoking history; moreover, an association with EGFR mutations has been suggested in several case reports. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 However, there is still a lack of research on the clinical characteristics of patients with miliary pulmonary metastases (MPM) or the genetic features of NSCLC with MPM.

Therefore, we compared the clinical and genetic characteristics of NSCLC patients with MPM to those of patients with nonmiliary pulmonary metastases (NMPM). We also analyzed the treatment modalities and survivals of those patients to help determine the treatment options for the patients with MPM.

METHODS

Study population

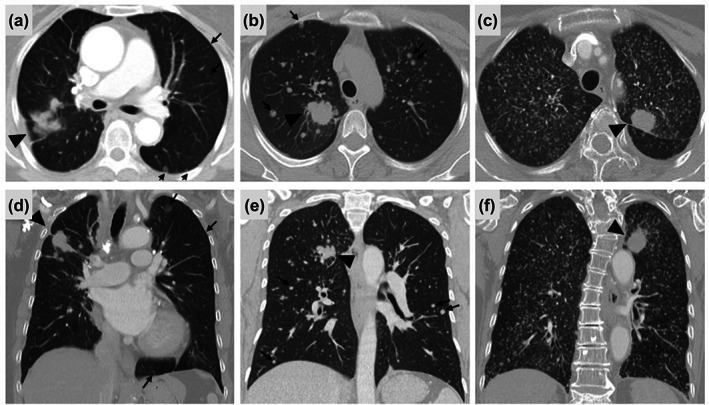

We conducted a retrospective case‐cohort study of patients diagnosed with NSCLC between January 2006 and December 2020 at Samsung Medical Center, which is a 1979‐bed referral hospital in Seoul, Republic of Korea. NSCLC patients with MPM (case) or NMPM (control) detected by chest computed tomography (CT) during the staging evaluation were included in the study. MPM was defined by both subjective and objective radiographic criteria in this study. Subjectively, it was defined as the presence of profuse tiny, discrete, round pulmonary nodules generally uniform in size and randomly distributed throughout the lungs. 14 , 15 Objectively, it was defined as >50 metastatic nodules <10 mm in greatest dimension. NMPM was objectively defined as ≤15 intrapulmonary metastatic nodules regardless of size. Representative chest CT findings of patients exhibiting MPM and NMPM are shown in Figure 1. Patients with diffuse pleural metastasis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, or multifocal ground‐glass opacities were excluded. Three times the number of patients in the MPM group were randomly extracted from among the NMPM patients and enrolled in the study. The case–control ratio of 1:3 was chosen as ratios greater than 1:3 usually have little additional gain on statistical power. 16 As different size cutoffs for miliary nodules (i.e., < 5 mm or <1 cm) have been reported, 13 , 17 patients with MPM were divided into two subgroups (≥5 or <5 mm) depending on the maximum size of the metastatic nodules.

FIGURE 1.

Representative radiological findings of (a, d) nonmiliary pulmonary metastases and (b, c, e, f) miliary pulmonary metastases. (a, d) The primary tumor (black arrowhead) is in the right upper lobe and multiple round variably‐sized nodules (black arrows) extend to the bilateral lungs. (b, e) The primary tumor (black arrowhead) is in the right upper lobe and countless nodules with a maximum size of >5 mm and <1 cm (black arrows) were spread across the bilateral lungs. (c, f) The primary tumor (black arrowhead) is in the left upper lobe, and numerous nodules with a maximum size <5 mm, were spread across the bilateral lungs.

Staging evaluation and data collection

The clinical characteristics of patients, including age at diagnosis, sex, smoking status, and tumor histology, were collected from electronic medical records. Data on tumor histology, genetic changes including EGFR mutations, ALK rearrangements, and KRAS mutations, and treatment modalities were also collected. Dates of death were collected from the patients' medical records or the database of the National Health Insurance Service.

Tumors were restaged according to the eighth edition of the TNM staging classification for lung cancer. 18 The routine staging evaluation included chest CT scans, abdominal and pelvic CT scans, positron emission tomography (PET) or PET/CT scans, bone scintigraphy, brain magnetic resonance imaging, and flexible bronchoscopy. Mediastinoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration of thoracic lymph nodes was performed according to our institutional protocol if needed during the staging evaluation. 19

EGFR and KRAS mutations and ALK immunohistochemistry

The methods of genotyping have been described in our previous article. 7 Briefly, to evaluate EGFR and KRAS gene mutations, genomic DNA was isolated from formalin‐fixed paraffin‐embedded (FFPE) tissue. DNA sequencing for EGFR mutations in exons 18–21 was performed using real‐time polymerase chain reaction and a peptide nucleic acid clamping EGFR mutation detection kit (Panagene Inc.). KRAS mutations in exons 12 and 13 were evaluated by Sanger sequencing. ALK protein expression was evaluated by immunohistochemistry (NCL‐ALK, clone 5A4, Novocastra or Ventana ALK CDx assay, clone D5F3, Ventana Medical Systems) with FFPE tissue.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or numbers (%). Categorical variables were compared using Pearson's χ2 test and continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal‐Wallis test. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method; the log‐rank test was used to compare subjects with MPM to those with NMPM. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed to identify factors significantly affecting OS. Significant variables (p < 0.05) in univariate analyses, and those of known clinical importance, were entered into multivariate analyses. The results are reported as unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All tests were two‐sided and a p‐value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 3.6.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of study population

Twenty‐six NSCLC patients were newly diagnosed with MPM at Samsung Medical Center between January 2006 and December 2020. Seventy‐eight patients, that is, three times the number of MPM patients, with NSCLC and NMPM were randomly enrolled in this study. As shown in Table 1, the median age of the study population was 63 (IQR: 52–68) years and 59 patients (57%) were male. Fifty‐six patients (54%) were never‐smokers. No significant differences in median age at diagnosis (58 vs. 68 years, p = 0.146) or the proportion of females (50% vs. 41%, p = 0.568) were observed between the MPM and NMPM groups. The proportion of patients without a smoking history was not different between the two groups (69% vs. 49%, p = 0.112), but the median amount of smoking by smokers in the miliary group was significantly higher than that of smokers in the nonmiliary group (0 vs. 8 pack‐years, p = 0.030). No significant differences in TNM stage were observed between the MPM and NMPM groups (T; p = 0.119, N; p = 0.436, M; p = 0.257). The MPM group showed higher tendency in the proportion of adenocarcinoma histology compared with the NPMM group (100% vs. 81%, p = 0.054). Additionally, the frequency of EGFR mutation was higher in the MPM than NMPM group (58% vs. 24%, p = 0.006). No difference in the proportion of patients with positive ALK immunohistochemistry was detected between the two groups (4% vs. 7%, p = 0.328). However, the frequency of KRAS mutation was significantly higher in the NMPM than MPM group (4% vs. 8%, p = 0.006).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants.

| Variable | Total (n = 104) | Miliary metastases (n = 26) | Nonmiliary metastases (n = 78) | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 63 (52–68) | 58 (50–65) | 64 (53–70) | 0.146 |

| Gender | 0.568 | |||

| Male | 59 (57) | 13 (50) | 46 (59) | |

| Female | 45 (43) | 13 (50) | 32 (41) | |

| Smoking status | 0.112 | |||

| Never smoker | 56 (54) | 18 (69) | 38 (49) | |

| Ex‐ or current smoker | 28 (27) | 8 (31) | 40 (51) | |

| Smoking amount (PY) | 0 (0–40) | 0 (0–10) | 8 (0–40) | 0.030 |

| T stage | 0.119 | |||

| T1 | 40 (38) | 14 (54) | 26 (33) | |

| T2 | 30 (29) | 8 (31) | 22 (28) | |

| T3 | 18 (17) | 3 (12) | 15 (19) | |

| T4 | 16 (15) | 1 (4) | 15 (19) | |

| N stage | 0.436 | |||

| N0 | 20 (19) | 6 (23) | 14 (18) | |

| N1 | 7 (7) | 0 (0) | 7 (9) | |

| N2 | 29 (28) | 7 (27) | 22 (28) | |

| N3 | 48 (46) | 13 (50) | 35 (45) | |

| M stage | 0.257 | |||

| M1a | 55 (53) | 11 (42) | 44 (56) | |

| M1b | 7 (7) | 1 (4) | 6 (8) | |

| M1c | 42 (40) | 14 (54) | 28 (36) | |

| Histology | 0.054 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 89 (86) | 26 (100) | 63 (81) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 11 (11) | 0 (0) | 11 (14) | |

| Other NSCLC | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | |

| EGFR mutation | 0.006 | |||

| Negative | 50 (48) | 7 (27) | 43 (55) | |

| Positive | 34 (33) | 15 (58) | 19 (24) | |

| Exon 19 deletion | 19 (18) | 6 (23) | 13 (17) | |

| Exon 20 insertion | 10 (10) | 4 (15) | 6 (8) | |

| Exon 21 L858R | 3 (3) | 3 (12) | 0 (0) | |

| Complex mutations a | 2 (2) | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | |

| Not available | 20 (19) | 4 (15) | 16 (21) | |

| ALK IHC | 0.328 | |||

| Negative | 61 (60) | 13 (50) | 48 (63) | |

| Positive | 6 (6) | 1 (4) | 5 (7) | |

| Not available | 35 (34) | 12 (46) | 23 (30) | |

| KRAS mutation | 0.006 | |||

| Wild‐type | 48 (47) | 6 (23) | 42 (55) | |

| Mutant | 7 (7) | 1 (4) | 6 (8) | |

| G12C | 3 (3) | 0 | 3 (4) | |

| G12D | 3 (3) | 1 (4) | 2 (3) | |

| G12R | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | |

| Not available | 47 (46) | 19 (73) | 28 (37) |

Note: Data are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

Abbreviations: ALK IHC, anaplastic lymphoma kinase immunohistochemistry; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; PY, pack‐years.

One patient had exon 19 deletion and exon 20 insertion, and another patient had exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R.

Treatment modalities of study population

Of all study participants, 82 patients (79%) received conventional chemotherapy or targeted therapy, while 22 patients (21%) received only supportive care. The proportion of patients who received chemotherapy was not different between the MPM and NMPM groups (73% vs. 81%, p = 0.579). In total, 52 patients (50%) received EGFR‐TKI as the first‐line treatment. The proportion of patients who received EGFR‐TKI treatment was significantly higher in the MPM than NMPM group (73% vs. 42%, p = 0.013). The EGFR‐TKIs used by the MPM group included gefitinib, erlotinib, afatinib, and osimertinib, whereas only gefitinib was used in the NMPM group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Treatment modalities of the participants.

| Variable | Total (n = 104) | Miliary metastases (n = 26) | Nonmiliary metastases (n = 78) | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 0.579 | |||

| Chemotherapy | 82 (79) | 19 (73) | 63 (81) | |

| Supportive care only | 22 (21) | 7 (27) | 15 (19) | |

| EGFR‐TKIs a | 52 (50) | 19 (73) | 33 (42) | 0.013 |

| Gefitinib | 41 (40) | 8 (31) | 33 (42) | |

| Erlotinib | 4 (4) | 4 (15) | 0 | |

| Afatinib | 3 (3) | 3 (12) | 0 | |

| Osimertinib | 4 (4) | 4 (15) | 0 | |

| ALK‐TKI | ||||

| Crizotinib b | 1 (1) | 1 (4) | 0 |

Abbreviations: ALK‐TKI, anaplastic lymphoma kinase‐tyrosine kinase inhibitor; EGFR‐TKIs, epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

As first line treatment.

As second line treatment.

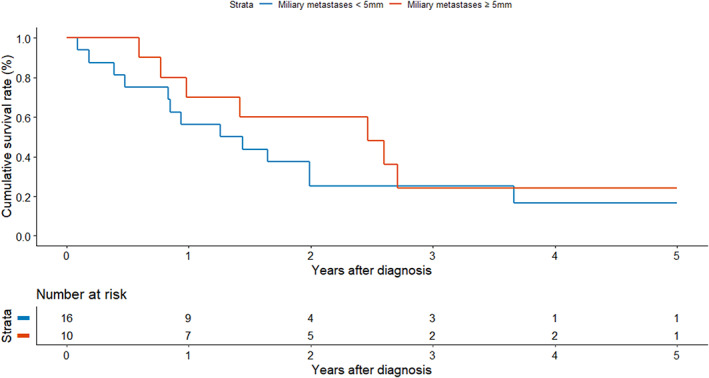

Subgroup analysis according to the size of miliary nodules in MPM group

Patients with MPM were divided into two subgroups according to the maximum size of the miliary nodules (16 subjects with nodules <5 mm in diameter and 10 subjects with nodules ≥5 mm in diameter); the baseline characteristics of these two subgroups were compared (Table 3). No significant differences in median age at diagnosis (61 vs. 56 years, p = 0.245), the proportion of females (50% vs. 50%, p = 0.999), or smoking status (75% vs. 60%, p = 0.650) were observed between the groups. TNM stage (T; p = 0.855, N; p = 0.711, M; p = 0.104) and the proportion of subjects with genetic mutations in the EGFR (56% vs. 60%, p = 0.935) and ALK gene (6% vs. 0%, p = 0.582) was not different between the two subgroups.

TABLE 3.

Baseline characteristics of the participants with miliary metastases according to the size of metastatic nodules (n = 26).

| Variable | Miliary metastases <5 mm (n = 16) | Miliary metastases ≥ 5 mm (n = 10) | p‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 61 (54–65) | 56 (48–64) | 0.245 |

| Gender | 0.999 | ||

| Male | 8 (50) | 5 (50) | |

| Female | 8 (50) | 5 (50) | |

| Smoking status | 0.650 | ||

| Never smoker | 12 (75) | 6 (60) | |

| Ex‐ or current smoker | 4 (25) | 4 (40) | |

| Smoking amount (PY) | 0 (0–5) | 0 (0–28) | 0.402 |

| T stage | 0.855 | ||

| T1 | 8 (50) | 6 (60) | |

| T2 | 5 (31) | 3 (10) | |

| T3 | 2 (12) | 1 (30) | |

| T4 | 1 (6) | 0 | |

| N stage | 0.711 | ||

| N0 | 4 (25) | 2 (20) | |

| N1 | 0 | 0 | |

| N2 | 5 (31) | 2 (20) | |

| N3 | 7 (44) | 6 (60) | |

| M stage | 0.104 | ||

| M1a | 5 (31) | 6 (60) | |

| M1b | 0 | 1 (10) | |

| M1c | 11 (69) | 3 (30) | |

| Histology | NA | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 16 (100) | 10 (100) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 0 | 0 | |

| Other NSCLC | 0 | 0 | |

| EGFR mutation | 0.935 | ||

| Negative | 5 (31) | 3 (30) | |

| Positive | 9 (56) | 6 (60) | |

| Exon 19 deletion | 3 (19) | 3 (30) | |

| Exon 20 insertion | 3 (19) | 1 (10) | |

| Exon 21 L858R | 2 (12) | 1 (10) | |

| Complex mutations | 1 (6) | 1 (10) | |

| Not available | 2 (12) | 2 (20) | |

| ALK IHC | 0.582 | ||

| Negative | 7 (44) | 6 (60) | |

| Positive | 1 (6) | 0 | |

| Not available | 8 (50) | 40 (40) | |

| KRAS mutation | 0.050 | ||

| Wild‐type | 6 (38) | 0 | |

| Mutant | 1 (6) | 0 | |

| G12C | 0 | 0 | |

| G12D | 1 (6) | 0 | |

| G12R | 0 | 0 | |

| Not available | 9 (56) | 10 (100) |

Note: Data are median (interquartile range) or n (%).

Abbreviations: ALK IHC, anaplastic lymphoma kinase immunohistochemistry; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NA, not available; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; PY, pack‐years.

Five‐year OS

The median OS time was 18.2 months for all patients; the median OS in patients with MPM and NMPM were 18.5 and 18.2 months, respectively. Table 4 shows the results of univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of 5‐year OS. The univariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed that age (HR, 1.03, p = 0.013) and tumor histology other than adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (HR, 4.28, p = 0.007) were associated with a poor 5‐year OS. These factors were also independent significant factors for poor 5‐year OS according to the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model (HR, 1.03 and 4.00, p = 0.019 and p = 0.010). Female gender and smoking history did not significantly affect 5‐year OS (HR, 0.70 and 1.42, p = 0.108 and p = 0.298, respectively). Moreover, no significant effect of miliary metastases (HR, 0.97, p = 0.893) or EGFR mutation (HR for sensitizing mutation and exon 20 insertion, 0.818 and 0.937, p = 0.818 and p = 0.397, respectively) was detected on 5‐year OS.

TABLE 4.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of 5‐year overall survival.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | p‐value | HR (95% CI) | p‐value |

| Age, years | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.013 | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 0.019 |

| Gender, female | 0.70 (0.45–1.08) | 0.108 | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Never smoker | Reference | |||

| Ex‐ or current smoker | 1.42 (0.83–2.42) | 0.298 | ||

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | Reference | Reference | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1.79 (0.89–3.61) | 0.101 | 1.71 (0.85–3.45) | 0.101 |

| Other NSCLC | 4.28 (1.50–12.2) | 0.007 | 4.00 (1.40–11.4) | 0.010 |

| T stage | ||||

| T1 | Reference | |||

| T2 | 1.17 (0.69–2.00) | 0.556 | ||

| T3 | 1.14 (0.60–2.16) | 0.684 | ||

| T4 | 1.42 (0.76–2.63) | 0.272 | ||

| N stage | ||||

| N0 | Reference | |||

| N1 | 1.61 (0.62–4.21) | 0.329 | ||

| N2 | 1.25 (0.65–2.42) | 0.506 | ||

| N3 | 1.38 (0.75–2.54) | 0.306 | ||

| M stage | ||||

| M1a | Reference | |||

| M1b | 1.76 (0.75–4.14) | 0.198 | ||

| M1c | 0.97 (0.62–1.52) | 0.884 | ||

| Miliary metastases, positive | 0.97 (0.58–1.60) | 0.893 | ||

| EGFR mutation | ||||

| Wild‐type | Reference | |||

| Sensitizing mutations a | 1.09 (0.54–2.19) | 0.818 | ||

| Exon 20 insertion | 0.65 (0.24–1.75) | 0.397 | ||

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; TKIs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

EGFR L858R, exon 19 deletion, and complex mutations (exon 19 deletion + L858R and exon 19 deletion + exon 20 insertion).

Survival analysis

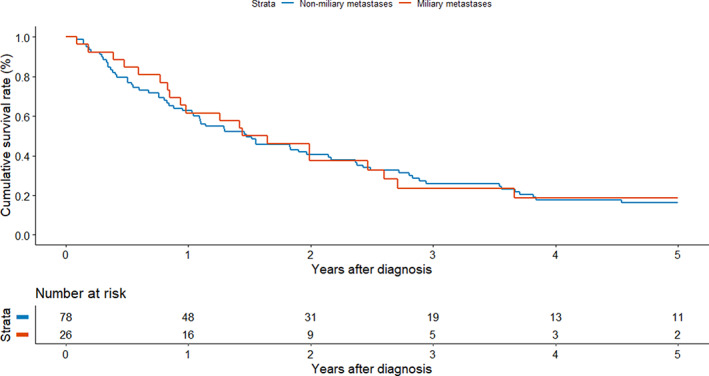

Kaplan–Meier survival plots of patients with MPM and NMPM are shown in Figure 2. The 5‐year OS rates of patients with MPM and NMPM were 19% and 16%, respectively (log‐rank, p = 0.900). MPM subgroup analysis according to miliary nodule size was also conducted. The 5‐year OS rates of patients with miliary nodules <5 and ≥5 mm in diameter were 16% and 24%, respectively (Figure 3; log‐rank, p = 0.360).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of patients with miliary metastases and nonmiliary metastases (log‐rank test, p = 0.900).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of patients with miliary metastases <5 mm and ≥5 mm (log‐rank test, p = 0.360).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the clinical characteristics of NSCLC patients with MPM detected during routine staging evaluations. All patients with MPM had adenocarcinoma histology, and the proportion of patients with adenocarcinoma histology was higher in the NMPM than MPM group (100% vs. 81%, p = 0.057). Additionally, the frequency of EGFR mutation was higher in the MPM than NMPM group (58% vs. 24%, p = 0.006). No significant difference in OS rate was observed between the two groups (p = 0.893). Interestingly, the presence of miliary metastases did not affect OS.

Recent case studies have evaluated the effects of MPM in patients with advanced lung cancer. In 1993, Umeki et al. reported five cases of MPM in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma, as confirmed by postmortem diagnosis. Histopathological features revealed multiple metastatic nodules with vigorous tumor emboli penetrating the perivascular tissue, which led to the rapid progression of pulmonary metastases. 20 As cancer genome analysis is increasingly a part of clinical care, another previous study showed the characteristics of MPM with five patients, characterized by a specific histological subtype (adenocarcinoma) and genotype (EGFR exon 19 deletions). 10 In this context, findings from two recent studies in Asia reported that a total of 70 (87.5%) NSCLC patients with MPM had EGFR mutations, thus extending the results of previous case reports. 12 , 15 In a retrospective cohort study of 163 patients with advanced NSCLC, Togashi et al. showed that the presence of an EGFR mutation (n = 77, 47%) was associated with MPM (odds ratio, 6.12 [95% CI: 1.58–27.97]). 12 However, that study did not report the outcome of TKI treatment in patients with MPM. Another study from Taiwan identified 85 advanced lung cancer patients with MPM and reported that EGFR mutation may improve the response to EGFR‐TKIs and OS. 15 The survival rate of our TKI‐treated group was higher than that of the non‐TKI‐treated group. As in previous studies, we detected a high EGFR mutation rate among patients presenting with MPM at the initial diagnosis.

The present study is the first to show no difference in survival rate between MPM and NMPM patients; previously, it was thought that the former had a poorer prognosis. In a case report, two patients with MPM who received conventional chemotherapy died 3–4 months after their lung cancer diagnosis, suggesting that MPM is associated with rapid disease progression. 11 According to a previous cohort study analyzing IASLC data, the 5‐year survival rate of subjects with contralateral/bilateral tumor nodules (M1a) was 20%, 5 similar to that of 18.5% for the MPM patients in this study. In contrast to previous results, the MPM patients in the present study did not have a lower mortality rate than the NMPM patients because EGFR mutation was confirmed at the time of diagnosis and TKIs were given as the first‐line treatment. Thus, physicians should be aware of the importance of detecting EGFR mutations and initiating treatment with TKIs in lung cancer patients with MPM.

Despite the higher prevalence of EGFR mutations in MPM patients, the presence of an EGFR mutation had no effect on survival in the univariate Cox regression. This finding contradicts previous research reporting better EGFR‐TKI responses in NSCLC patients with intrapulmonary metastases and EGFR mutations. 15 , 21 However, more than half of the patients in these previous studies died within 1 year after the initial diagnosis, which represents a shorter survival time than that in the present study. Interestingly, there was another study that objectively measured the tumor burden via metabolic tumor volume on PET/CT in MPM patients. 17 Although the patients had activating EGFR mutation, high tumor burden was an important predictor of a poor prognosis of lung cancer in that study. Another study also reported a poorer prognosis for NSCLC patients with activating EGFR mutations who had more metastatic sites. 22

MPM pattern is commonly observed in highly vascular tumors like melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and metastatic thyroid carcinoma. 23 For primary lung cancer, it has been suggested that there is a connection between miliary pulmonary metastasis and bone metastasis. The hypothesis posits that primary lung cancer initially spreads to the bone through the bloodstream, followed by the dissemination of multiple tumor emboli from secondary bone metastasis sites, leading to miliary metastasis. 20 In a similar manner to miliary tuberculosis, where Mycobacterium tuberculosis spreads throughout the lungs via the bloodsteam, 24 MPM is a rare pattern of hematogenous metastasis to the lungs. Remarkably, the development of MPM in lung cancer has been correlated with the presence of EGFR mutations. Paracrine loops involving interplay between tumor and stromal cells enable EGFR to facilitate invasion across tissue barriers, sustain clusters of circulating tumor cells, and establish colonization in distant organs. 25 Therefore, patients with MPM harboring EGFR mutations may have a relatively elevated tumor burden and disseminate cancer cells via the bloodstream.

Several limitations of our study should be discussed. First, it was conducted at a single referral center, which may limit the generalizability of the data. Second, we only evaluated all‐cause mortality, and not cancer‐specific mortality, due to a lack of detailed information for some patients who were transferred to other hospitals or lost to follow‐up. Third, the information on other genetic alterations including ROS1 or RET rearrangement and other rare mutations was not available since the study subjects did not undergo next generation sequencing.

In conclusion, MPM in patients with NSCLC was significantly related to EGFR mutation. The OS rate of the MPM group was not inferior to that of the NMPM group. NSCLC patients with an initial presentation of MPM should be thoroughly evaluated for EGFR mutations.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have made significant contributions to this study.

Study concept and design: Y.I. and S‐W.U. Acquisition of data: B‐H.J., K.L, H.K. and S‐W.U. Analysis and interpretation of the data: H.C., Y.I., and S‐W.U. Drafting of the manuscript: H.C., Y.I., and S‐W.U. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Study supervision: S‐W.U.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by Future Medicine 20*30 Project of the Samsung Medical Center (#SMO1230021).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Choi H, Im Y, Jeong B‐H, Lee K, Kim H, Um S‐W. Clinical characteristics of miliary pulmonary metastases in non‐small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2023;14(22):2168–2176. 10.1111/1759-7714.15003

Hanmil Choi and Yunjoo Im contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganti AK, Klein AB, Cotarla I, Seal B, Chou E. Update of incidence, prevalence, survival, and initial treatment in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7:1824–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seo JB, Im JG, Goo JM, Chung MJ, Kim MY. Atypical pulmonary metastases: spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics. 2001;21:403–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, Rami‐Porta R, Asamura H, Eberhardt WEE, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eberhardt WE, Mitchell A, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the M descriptors in the forthcoming eighth edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:1515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA. 2014;311:1998–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choi Y, Kim KH, Jeong BH, Lee KJ, Kim H, Kwon OJ, et al. Clinicoradiopathological features and prognosis according to genomic alterations in patients with resected lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:5357–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andreu J, Mauleon S, Pallisa E, Majo J, Martinez‐Rodriguez M, Caceres J. Miliary lung disease revisited. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2002;31:189–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Patil T, Pacheco JM. Miliary metastases in non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laack E, Simon R, Regier M, Andritzky B, Tennstedt P, Habermann C, et al. Miliary never‐smoking adenocarcinoma of the lung: strong association with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletion. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:199–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sekine A, Katano T, Oda T, Ikeda S, Iwasawa T, Satoh H, et al. Miliary lung metastases from non‐small cell lung cancer with exon 20 insertion: a dismal prognostic entity: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2018;9:673–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Togashi Y, Masago K, Kubo T, Sakamori Y, Kim YH, Hatachi Y, et al. Association of diffuse, random pulmonary metastases, including miliary metastases, with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2011;117:819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hsu F, Nichol A, Toriumi T, De Caluwe A. Miliary metastases are associated with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non‐small cell lung cancer: a population‐based study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56:1175–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J. Fleischner society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246:697–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu SG, Hu FC, Chang YL, Lee YC, Yu CJ, Chang YC, et al. Frequent EGFR mutations in nonsmall cell lung cancer presenting with miliary intrapulmonary carcinomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wacholder S, Silverman DT, McLaughlin JK, Mandel JS. Selection of controls in case‐control studies. Iii design options. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1042–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim HJ, Kang SH, Chung HW, Lee JS, Kim SJ, Yoo KH, et al. Clinical features of lung adenocarcinomas with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and miliary disseminated carcinomatosis. Thorac Cancer. 2015;6:629–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rami‐Porta R, Bolejack V, Giroux DJ, Chansky K, Crowley J, Asamura H, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: the new database to inform the eighth edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1618–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Um SW, Kim HK, Jung SH, Han J, Lee KJ, Park HY, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound versus mediastinoscopy for mediastinal nodal staging of non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2015;10:331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Umeki S. Association of miliary lung metastases and bone metastases in bronchogenic carcinoma. Chest. 1993;104:948–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kobayashi M, Takeuchi T, Bandobashi K, et al. Diffuse micronodular pulmonary metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma predicts gefitinib response in association with epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:1621–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Park JH, Kim TM, Keam B, Jeon YK, Lee SH, Kim DW, et al. Tumor burden is predictive of survival in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer and with activating epidermal growth factor receptor mutations who receive gefitinib. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14:383–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kimmig L, Bueno J. Miliary nodules: not always tuberculosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1858–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sharma SK, Mohan A, Sharma A, Mitra DK. Miliary tuberculosis: new insights into an old disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:415–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Uribe ML, Marrocco I, Yarden Y. EGFR in cancer: signaling mechanisms, drugs, and acquired resistance. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]