Abstract

Objective

Diagnostic delay is high in acromegaly and leads to increased morbidity and mortality. The aim of this study is to systematically assess the most prevalent clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities of acromegaly at time of diagnosis.

Design

A literature search (in PubMed, Embase and Web of Science) was performed on November 18, 2021, in collaboration with a medical information specialist.

Methods

Prevalence data on (presenting) clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities at time of diagnosis were extracted and synthesized as weighted mean prevalence. The risk of bias was assessed for each included study using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data.

Results

Risk of bias and heterogeneity was high in the 124 included articles. Clinical signs and symptoms with the highest weighted mean prevalence were: acral enlargement (90%), facial features (65%), oral changes (62%), headache (59%), fatigue/tiredness (53%; including daytime sleepiness: 48%), hyperhidrosis (47%), snoring (46%), skin changes (including oily skin: 37% and thicker skin: 35%), weight gain (36%) and arthralgia (34%). Concerning comorbidities, acromegaly patients more frequently had hypertension, left ventricle hypertrophy, dia/systolic dysfunction, cardiac arrhythmias, (pre)diabetes, dyslipidemia and intestinal polyps- and malignancy than age- and sex matched controls. Noteworthy, cardiovascular comorbidity was lower in more recent studies. Features that most often led to diagnosis of acromegaly were typical physical changes (acral enlargement, facial changes and prognatism), local tumor effects (headache and visual defect), diabetes, thyroid cancer and menstrual disorders.

Conclusion

Acromegaly manifests itself with typical physical changes but also leads to a wide variety of common comorbidities, emphasizing that recognition of a combination of these features is key to establishing the diagnosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11102-023-01322-7.

Keywords: Acromegaly, Diagnosis, Prevalence, Symptoms, Signs, Comorbidities

Introduction

Acromegaly is a rare disease in which there is an excess of growth hormone (GH) release by the pituitary, usually due to a benign pituitary adenoma. Symptoms arise due to a combination of both local effects, produced by a mass effect of the pituitary tumor, and systematic effects due to chronic elevation of GH and insulin-like-growth factor-1 (IGF-1) levels. In addition to the morphological changes and physical complaints, this condition also leads to substantial comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, sleep apnea and neoplasms [1]. As a result, mortality is increased in acromegaly [2]. The presence and extent of clinical features and morbidities in acromegaly patients depend on the duration of the illness, which makes early diagnosis and treatment of great importance to prevent complications.

However, diagnostic delay in this patient group is high. While studies before the 1990’s showed that average delay between 10 and 20 years was usual, more recent studies estimated it to be 4.5 to 5.5 years, yet a substantial part of patients still waits for over 10 years to be diagnosed correctly[3–6]. Reasons for the delay in recognition of acromegaly are the relative unfamiliarity of physicians with the disease and a lack of pathognomic symptoms at disease onset. Since the prevalence of acromegaly in the general population is estimated between 2.8 and 13.7 cases per 100,000 people, the disease remains relatively unknown [4]. Clinical signs and symptoms usually develop slowly as (a combination of) vague complaints and therefore are not easily recognized as acromegaly symptoms by patients and medical caregivers. As a result, patients have often already visited several medical specialists before the diagnosis is made [7–10]. This diagnostic delay leads to increased morbidity and mortality [3].

Previous research shows the difficulty of identifying (clusters of) manifestations, based on current knowledge of symptoms and clinical features, that should raise suspicion of acromegaly in medical caregivers [1]. Current information about known signs and symptoms during the clinical course of acromegaly is based on observational studies and reviews. However, no systematic approach in describing the most prevalent symptoms at time of diagnosis in acromegaly patients have been performed yet and so clear overviews are currently lacking. Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review was to assess the most prevalent clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities of acromegaly at time of diagnosis, before any treatment was started. The secondary aim was to identify symptoms of which follow-up most often led to the diagnosis of acromegaly.

Methods

This review is reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) [11] and registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022344505).

Search strategy

To identify all relevant publications we conducted systematic searches in the bibliographic databases in PubMed, Embase and Web of Science (Core Collection) from inception to November 18, 2021, in collaboration with a medical information specialist. The following terms were used (including synonyms and closely related words) as index terms or free-text words: “Acromegaly”, “Growth hormone overproduction”, “Early diagnosis”, “Incidental findings”. The references of the identified articles were searched for relevant publications. Duplicate articles were excluded. All languages were excepted. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in Online Appendix A.

Selection process

Two reviewers (TS and CB) independently screened all potentially relevant titles and abstract for eligibility. If necessary, the full text article was checked for the eligibility criteria. Differences in judgement were resolved through a consensus procedure. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) original data; (ii) N ≥ 5; (iii) vast majority of adults (≥ 18 years at time of diagnosis); (iv) articles that report prevalence of clinical signs, symptoms and/or comorbidities at time of diagnosis and before treatment of acromegaly; (v) any setting. We excluded studies if they were: (i) letters, (systematic) reviews, meta-analysis, case reports, conference abstracts, viewpoints; (ii) animal or in vitro studies; (iii) language other than English or Dutch; (iv) papers with a mixture of patients (i.e. treated/untreated) in which no clear distinction in subgroups of the results was made. To minimize duplication of cohorts, study period and—variables were checked in studies from the same center. If study period and/or—variables differed, both studies were included. If study period and—variables were overlapping, we excluded the study with the lowest sample size.

Data assessment

The full text of the selected articles was obtained for further review. Data was extracted from selected articles and included the following characteristics:

Study: year of publication, aim, design and period;

Participants: number (N), geographical location (country), sex (% males) and age (range, mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range), control group (yes/no);

Data and results: prevalence of clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities in acromegaly at time of diagnosis and before treatment (presented as observed n/total N, or % of patients), and if available also for controls; and symptoms that led to the correct diagnosis of acromegaly (“presenting symptom”)

Statistical analysis

Effect measures for the current systematic review were: number of studies describing the clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities, prevalence of the clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities in acromegaly patients (and if available: in controls)—given as range and weighted mean prevalence (total number of patients with the feature divided by total number of patients in studies reporting the feature) for presenting symptom/comorbidity: weighted mean frequency (total number of patients with that presented with that feature divided by total number of patients in studies reporting on that feature). When the numerator and percentage were stated clearly, the denominator was calculated by the reviewers if not reported in the study; or when the denominator and percentage were stated clearly, the numerator was calculated. The same was done for the presenting symptom. Since the time frame of included studies in current systematic review was wide (50 years) and diagnostic delay has shortened from 10–20 to 4.5–5.5 years, clinical presentation might also have changed. Therefore, we performed subanalysis on weighted mean prevalence in two groups based on the median publication date of all included studies (old versus recent studies). Weighted mean prevalence of clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities at time of diagnosis of acromegaly were also compared to prevalence data from the general population. When available, data was compared to both global and a Dutch population, otherwise we tried to find a mixture of both Western and non-Western control populations. Lastly, we compared our data on prevalence of different comorbidities to data from the Liege Acromegaly Survey (LAS) Database; a large database consisting of 3173 acromegaly patients from centers in ten European countries (Spain, Netherlands, France, Sweden, Belgium, Italy, Czech Republic, Germany, Portugal and Bulgary) [12].

Risk of bias assessment

The methodology of the full text papers was evaluated using The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data [13]. According to a recent systematic review, this tool was the most appropriate available tool for quality assessment of prevalence studies [14]. In order to grade sample size, a sample size analysis was calculated using the formula proposed by the JBI tool, based on previous literature [15, 16]: n = (Z2P(1-P))/d2, where n = sample size, Z = z statistic for a level of confidence, P = expected prevalence and d = precision. Based on Z = 1.96, d = 0.05 and P of 23.4% (mean prevalence of all found clinical features in current review), n should be 275 or more to be considered low risk of bias.

Results

Search results

The literature search generated a total of 14,140 references; 4429 in PubMed, 6160 in Embase and 3551 in Web of Science. After removing duplicates of references that were selected from more than one database, 7071 references remained. The flow chart of the search and the selection process is presented in Fig. 1. In case of uncertainty about the (previous) treatment status of patients, studies were excluded. Studies were also excluded if both reviewers did not consider the outcome measures usable, for instance outcomes that were shown as continuous variables (blood pressure given in mmHg). Three exceptions were made for duplication of cohorts [17–22] because excluding them would have led to a relevant loss of data of other variables. The variables that were reported in both studies were type 2 diabetes mellitus (three times) and hypertension (one time) and subanalysis showed that exclusion of the possible double data did not lead to significant differences in the weighted mean prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus or hypertension (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search and the selection procedure of studies

Study characteristics

Study characteristics are given in Online Appendix B. Publication date ranged from 1973 to 2021 and median stud period was 2013. Data originated from 38 countries of 6 continents (Asia, Africa, North and South America, Europe and Australia). Sample size was < 50 for 49, 50–100 for 36, 100–250 for 24 and > 250 for 15 studies, respectively. For most studies, mean age was between 40 and 50 years and sex was equally distributed.

Risk of bias assessment

Assessment of risk of bias is given in detail for each included study as well as a summary graph (Online Appendix C). In about 50% of the studies, some form of selection bias (question 1 and 2) was present. This was mainly due to large numbers of studies that included only acromegaly patients who were planned for surgical removement of the pituitary tumour and/or studies that only included healthy participants (e.g. exclusion of patients with infection, cardiovascular -, renal- or hepatic disease). When considering sample size, only 12 out of 124 studies included sufficient participants according to our sample size analysis. Classification bias (question 5) appeared to be low. Approximately 60% of the studies reported a valid and/or standard and reliable method in the identification of the symptoms (e.g. definition of hypertension, use of oral glucose tolerance test to determine diabetes), while for a large number of symptoms the method of identification was not clear, not valid or not standard for all participants (no description of measurement, actively asked upon or not). Also, a substantial proportion of the studies did not clearly report the prevalence, including both the percentage as well as the nominator and denominator (e.g. a missing denominator). Lastly, for about one third of the included studies the response rate was unclear—it was not described how many patients were eligible for the study, thereby being unclear about the response rate.

Prevalence of clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities at time of diagnosis of acromegaly

A complete overview of symptoms and comorbidities at the time of acromegaly diagnosis are given in Fig. 2 and 3. The top 10 of most prevalent symptoms with the highest weighted mean were: acral enlargement (90%;facial features (65%; including prognatism/jaw enlargement: 56%, nose enlargement: 29% and thickening of lips: 25%), oral changes (including increased tooth gap: 62%, macroglossia: 59% and increased denture size: 31%), headache (59%), fatigue/tiredness (53%, including daytime sleepiness: 48%), hyperhidrosis (47%), snoring (46%), skin changes (including oily skin: 37% and thicker skin: 35%), weight gain (36%) and arthralgia (34%). Top 10 of most frequent comorbidities were: myocardial/left ventricle hypertrophy (59%), hypercalciuria (55%), endometrial polyp/myoma uteri (53%), fatty liver (47%), diastolic dysfunction (46%), thyroid nodule (44%), hypertension (38%; including intracranial hypertension: 30%), prediabetes (34%; impaired fasting glucose and glucose intolerance), metabolic syndrome (34%) and digestive polyp (29%).

Fig. 2.

Clinical signs and symptoms (N/N for weighted mean): weight mean [range]

Fig. 3.

Comorbidities (N/N for weighted mean): weight mean [range]

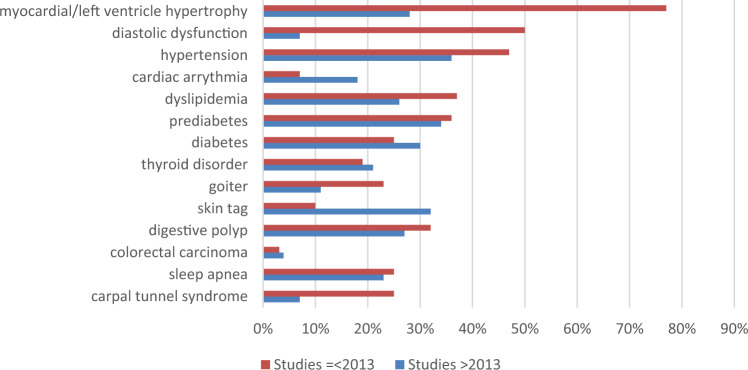

Subanalysis based on publication date

We performed subanalysis for clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities at time of diagnosis of acromegaly, based on the median publication date (see Fig. 4 and 5). Older studies (publication date ≤ 2013) reported higher prevalence of snoring (63% versus 45%), skin thickening (56% versus 33%), backache (34% versus 3%) and erectile dysfunction/vaginal dryness (39% versus 18%), while recent studies (publication date > 2013) reported higher prevalence of oral changes (prognatism: 56% versus 43%, macroglossia: 66% versus 10%, increased denture size: 75% versus 10%), headache (61% versus 39%), weight gain (41% versus 21%), loss of libido (21% versus 10%) and voice changes (33% versus 12%). Concerning cardiovascular comorbidities, older studies reported a (much higher) frequency of myocardial/left ventricle hypertrophy (77% versus 28%), diastolic dysfunction (50% versus 7%), hypertension (47% versus 36%) and dyslipidemia (37% versus 26%), while cardiac arrhythmia was more prevalent in the more recent studies (18% versus 7%). Older studies also reported higher prevalence of goiter (23% versus 11%) and carpal tunnel syndrome (25% versus 7%). Prevalence of (pre)diabetes (36%/25% versus 34%/30%), thyroid disorders (19% versus 21%), sleep apnea (25% versus 23%) and digestive polyps (32% versus 27%) was alike in both groups. Frequency of skin tags was higher in the recent studies (10% versus 32%).

Fig. 4.

Clinical signs and symptoms at time of diagnosis for two groups according to publication date

Fig. 5.

Comorbidities at time of diagnosis for two groups according to publication date

Compared to controls

When considering studies that also included age- and sex matched controls, patients with (untreated) acromegaly more frequently have hypertension, left ventricle hypertrophy, dia/systolic dysfunction, cardiac arrhythmias, (pre)diabetes, dyslipidemia and intestinal polyps and—malignancy [22–29]. Also, some studies report a higher frequency of previously mentioned and other comorbidities (i.e. obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, conductive hearing dysfunction), but comparative tests are lacking [30–37]. Two studies did not report a difference in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes or hypercholesterolemia [23, 26]. Data on the prevalence of colon polyps in acromegaly patients compared to patients with irritable bowel syndrome are conflicting: two studies show a higher frequency [38, 39], while another study did not find a difference [17]; the only study reporting colorectal neoplasms found a higher prevalence in acromegaly patients [39]. Compared to patients with non-functioning pituitary adenoma (NFA), three studies (including a total of 301 NFA and 156 acromegaly patients) found that acromegaly patients did not have a higher prevalence of diabetes, dyslipidemia, headache, visual defects, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, cardiac arrhythmias, coronary artery disease or fatigue [40–42]. They did have higher prevalence of acral enlargement and carpal tunnel syndrome [40, 41], while results on hypertension are conflicting [41, 42].

Compared to data from the general population

Table 1 shows prevalence data of common clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities in acromegaly patients, compared to prevalence data in the general population. Clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities that were highly prevalent in acromegaly patients, but not often seen in the general population were: hyperhidrosis, macroglossia, left ventricle hypertrophy, diabetes and sleep apnea. Clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities that were more frequent in acromegaly patients, but also common in the general population were: fatigue, diastolic dysfunction, fatty liver disease, osteoporosis, depression and voice problems. Others (headache, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, arthralgia,, thyroid nodule/goiter, digestive polyp and acne) were common and alike in both populations. Although rare in both populations, the prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome, papillary thyroid and colorectal cancer were respectively doubled and more than tenfold higher (for both cancers) in acromegaly patients.

Table 1.

Weighted mean prevalence of clinical sign, symptom or comorbidity in acromegaly compared to prevalence in the general population

| General population | ACM | Difference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age | Men | Geo | Year | Ref | Prev | Prev | ||

| Headache | 205,000 | Adults | EU | 2010 | [67] | 53% | 59% | + 5% | |

| All | GL | 2006 | [68] | 46% | + 13% | ||||

| Hyperhidrosis | 14,336 | 16–70 | 64% | GE | 2013 | [69] | 16% | 47% | + 31% |

| 385,597 | GL | 2019 | [70] | 1–38% | + 9–46% | ||||

| Macroglossia | 5150 | 13–83 | 45% | TUR | 2003 | [71] | 1% | 59% | + 58% |

| 4926 | 12–80 | IND | 2013 | [72] | 2% | + 57% | |||

| Fatigue | 9062 | ≥ 18 | 46% | NL | 2003 | [73] | 35% | 53% | + 18% |

| 1,140,959 | All | GL | 1992 | [74] | 5–45% (most 20–30%) | + 8–48% (+ 23–33%) | |||

| Cardiac/left ventricle hypertrophy | 149,803 | 18–93 | 42% | NL | 2017 | [75] | 0.5% (18-65y) 2% (≥ 65y) | 59% | + 57% |

| 11,597 | 54 ± 11 | 46% | CHI | 2022 | [76] | 15% | + 44% | ||

| 4976 | 17–90 | 45% | ENG | 1988 | [77] | 16–19% | + 40–43% | ||

| Diastolic dysfunction | 2042 | ≥ 45 | USA | 2000 | [78] | 28% | 45% | + 17% | |

| 6075 | Adults |

ENG USA AUS ITA |

2014 | [79] | 11–36% | + 9–34% | |||

| Hypertension | 149,803 | 18–93 | 42% | NL | 2017 | [75] |

23% (18-65y) 69% (≥ 65y) |

38% | − 7% |

| 259,011 | Adults | GL | 2003 | [80] | 30% | + 8% | |||

| Metabolic syndrome | 74,857 |

M 42.5 F 43 |

43% | NL | 2020 | [81] |

18% (M) 11% (F) |

34% | + 20% |

| 10,368 | ≥ 20 | 42% | IRA | 2003 | [82] | 34% | 0% | ||

| 13,656 | 18–80 | L-A | 2011 | [83] | 25% | + 9% | |||

| 1104 | 18–74 | 44% | SPA | 2008 | [84] | 29% | + 5% | ||

| Fatty liver | 167,729 | 18–93 | 38% | NL | 2017 | [85] | 22%2 | 47% | + 25% |

| 8,515,431 | GL | 2016 | [86] | 25% | + 22% | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 149,803 | 18–93 | 42% | NL | 2017 | [75] |

3% (18-65y) 12% (≥ 65y) |

29% | + 23% |

| All | GL | 2020 | [87] | 6% | + 23% | ||||

| 4% (15–49y) | + 25% | ||||||||

| 15% (50–69y) | + 14% | ||||||||

| 22% (70 + y) | + 7% | ||||||||

| Artralgia | 3664 | ≥ 25 | 50% | NL | 2003 | [88] | 54%3 | 34% | − 19% |

| GL | 2011 | [89] | 30% | + 4% | |||||

| Sleep apnea | 2089 | 18–70 | NL | 2012 | [90] | 7%4 | 24% | + 17% | |

| All | GL | 2017 | [91] | 9–38% | − 14–+ 15% | ||||

| Digestive polyp | 462 | 50–75 | 47% | NL | 2021 | [92] | 34% | 29% | − 4% |

| 3066 | M 55/60 | 61% | CHI | 2020 | [93] | 18% | + 11% | ||

| 1,604 | 47 | IND | 2016 | [94] | 11% | + 18% | |||

| 946 | M 49 | 83% | MEX | 2010 | [95] | 6–10% | |||

| 12,574 | 55–64 | EU | 2016 | [96] | 31% | − 2% | |||

| Colorectal cancer | 2,3 million | ≥ 19 | NL | 2004 | [97] | 0.3% | 3% | + 3% | |

| 534,056 | ≥ 15 | GL | 2020 | [98] | 0.4% | + 3% | |||

| Osteoporosis | Nation-wide | ≥ 50 | GE | 2013 | [99] | 26% | 29% | + 3% | |

| 103,334,579 | 15–105 | GL | 2021 | [100] | 18% | + 11% | |||

| Thyroid nodule/goiter | 96,278 | 18–65 | 46% | GE | 2004 | [101] |

32% (M) 34% (F) |

55% (44% + 11% | − 4% |

| 74,397,483 | Adults | GL | 2022 | [102] | Nodule: 25% | + 10% | |||

| Papillary thyroid cancer | Nation-wide | NL | 2019 | [103] | 0.02%5 | 4% | + 4% | ||

| 175,000,000 | All | 49% | CHI | 2016 | [104] | 0.04%5 | + 4% | ||

| USA | 1982 | [105] | 0.02% (M)5 | + 4% | |||||

| 0.07% (F)5 | + 3% | ||||||||

| Depression | Nation-wide | 18–64 | NL | 2009 | [106] | 5% | 22% | + 17% | |

| 1,112,573 | Adults | GL | 2018 | [107] | 13% | + 9% | |||

| Acne | 12,377 | 18–74 | 46% | EU | 2017 | [108] | 19% | 12% | − 7% |

| GL | 2012 | [109] | 9% | + 3% | |||||

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | 2466 | 25–74 | 34% | SE | 1997 | [110] | 4% | 7% | + 4% |

| 379 | 50–89 | JAP | 2020 | [111] | 5% | + 2% | |||

| 390,801,864 | EU | 2017 | [112] | 0.3–43% (most 3–4%%) | − 36% to + 7% (2–3%) | ||||

| Voice problems | 74,351 | > 18 | 44% | SE | 2019 | [113] | 17%6 | 28% | + 11% |

| 21,476 | ≥ 60 | USA, BRA, SCO | 2014 | [114] | 5–29% | − 1 to + 23% | |||

ACM acromegaly, BRA Brazil, EU Europe, F females, Geo geographic location, GE Germany, GL global, IND India, IRA Iran, JAP Japan, Prev prevalence, M males, NL Netherlands, L-A Latin-American countries, MEX Mexico, ref reference, SCO Scotland, SE Sweden, SP Spain, TUR Turkey, UK United Kingdom, USA United States of America, y years

1heart failure

2non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

3musculoskeletal pain during the survey

4sleep breathing disorder during the survey

5all thyroid cancers

6tire, strain or hoarse voice when talking

Compared to data from the liege acromegaly survey (LAS) database

Comorbidities with higher prevalences in current study than in the LAS Database were: cardiac/left ventricle hypertrophy (59% versus 16%), diastolic dysfunction (45% versus 2% [heart failure]), hypertension (38% versus 29%), digestive polyp (28% versus 13%), osteoporosis (29% versus 12%) and thyroid nodule/goiter (55% versus 34%). Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (29% versus 28%) and sleep apnea (24% versus 26%) were alike.

Clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities leading to the diagnosis of acromegaly

In total, 59 presenting symptoms and comorbidities were mentioned in 17 different studies [8–10, 12, 43–55]. Clusters were made based on the frequency of the presenting feature: frequent (≥ 10%), less frequent (4–9%) or rare (≤ 3%) (Table 2). Clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities that most often led to diagnosis of acromegaly were acral enlargement, headache, facial changes, diabetes, prognatism, thyroid cancer, visual defect, menstrual disorder, osteoporosis and transient ischemic attack.

Table 2.

Presenting clinical sign, symptom or comorbidity leading to diagnosis of acromegaly

| Symptom | N | Range | WM (N) | Symptom | N | Range | WM (N) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequent (≥ 10%) | Acral enlargement | 15 | 14–71% | 31% (8) | Diabetes | 5 | 2–16% | 11% |

| Headache | 17 | 4–50% | 21% (11) | Prognatism | 3 | 3–39% | 15% (2) | |

| Facial changes | 8 | 7–43% | 15% (5) | Thyroid cancer | 1 | 15% | ||

| Less frequent (4–9%) | Visual defect | 4 | 5–9% | 9% (2) | Fatigue | 5 | 1–25% | 5% (3) |

| Menstrual disorder | 11 | 3–24% | 8% (8) | Weight gain | 4 | 1–18% | 5% (2) | |

| Osteoporosis | 1 | 8% | Infertility | 3 | 1–11% | 5% (3) | ||

| TIA | 1 | 8% | Heart disease | 2 | 5–13% | 5% (1) | ||

| Paresthesia | 2 | 2–7% | 7% (1) | Depression | 1 | 5% | ||

| Kidney stones | 2 | < 1–7% | 7% (1) | Arthralgia | 10 | 1–14% | 4% (7) | |

| Congestive HF | 1 | 7% | Sleep apnea | 6 | 1–15% | 4% (4) | ||

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 7% | Voice changes | 2 | 1–10% | 4% (2) | ||

| Vision problems | 11 | < 1–14% | 6% (8) | Audition disorder | 2 | 1–4% | 4% (2) | |

| Sweating increased | 11 | 2–18% | 6% (6) | Molluscum | 2 | 1–4% | 4% (1) | |

| Hirsutism | 2 | 5–6% | 6% (1) | Tooth gap increase | 1 | 4% | ||

| Thyroid disorder | 5 | < 2–8% | 6% (3) | Thyroid nodule | 1 | 4% | ||

| Erectile dysfunction | 2 | 4–8% | 6% (2) | Thoracic pain | 1 | 4% | ||

| Glucose intolerance | 1 | 6% | Nausea | 1 | 4% | |||

| Hypertension | 7 | 1–13% | 5% (5) | Osseous pain | 1 | 4% | ||

| CTS | 6 | 4–17% | 5% (4) | Semi-closed eye | 1 | 4% | ||

| Rare (≤ 3%) | Galacthorrea | 7 | 2–11% | 3% (6) | Vertigo | 2 | 1–1% | 1% (2) |

| Jaw pain | 1 | 3% | Sinusitis | 2 | < 1–1% | 1% (1) | ||

| Damaged teeth | 1 | 3% | Acne | 1 | 1% | |||

| Loss of libido | 1 | 3% | Gynaecomastie | 1 | 1% | |||

| Back pain | 4 | 1–7% | 2% (3) | Seizure | 1 | 1% | ||

| Respiratory failure | 2 | 2–3% | 2% (2) | Syncope | 1 | 1% | ||

| Snoring | 2 | < 2–2% | Breast cancer | 1 | 1% | |||

| Nasal symptoms | 1 | 2% | Lung cancer | 1 | 1% | |||

| Photosensitivity | 1 | 2% | Any ENT comp | 1 | 1% | |||

| Thirst (without DI) | 1 | 2% | Skin tag | 1 | < 1% | |||

| Asthenia | 3 | 1–9% | 1% (1) |

Compl. complication, CTS carpal tunnel syndrome, DI diabetes insipidus, ENT ear, nose and throat, HF heart failure, N number of studies reporting the symptom, TIA transient ischemic attack, WM weighted mean frequency

Discussion

This is the first systematic review reporting on the prevalence of clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities at time of diagnosis of acromegaly. Acromegaly is a chronic multisystemic condition, leading to a wide variety of possible symptoms and complaints. While pathognomic symptoms are lacking, the outline of a disease specific presentation that should raise suspicion of acromegaly is of importance. Due to the current diagnostic delay, a lot of symptoms and clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities can already be present at time of diagnosis. During (physical) examination, changes in physical appearance (acral enlargement, typical facial and oral features) combined with complaints of skin changes (thicker and oilier skin, hyperhidrosis) and seem to be most disease specific. More general complaints of headache, fatigue, snoring, voice changes (hoarseness, voice deepening), arthralgia, and depression can also be found. The rate of comorbidities before treatment of acromegaly is high, mainly comprising common conditions such as hypertension, thyroid disorder and polyps of the digestive tract, while the presence of left ventricle hypertrophy, fatty liver disease, (pre)diabetes and sleep apnea were typical and more specific for acromegaly. Noteworthy, clinical presentation regarding cardiovascular comorbidities (left ventricle hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, hypertension and dyslipidemia) substantially improved over the years when comparing old versus recent studies. Carpal tunnel syndrome, colorectal and papillary thyroid carcinoma were not common, but have a higher frequency in acromegaly than in the general population.

While oral changes (macroglossia, jaw enlargement with increased tooth gap and denture size) were common in acromegaly at time of diagnosis, these were not often presenting complaints. The same accounts for erectile dysfunction, which were the presenting complaint that led to follow-up in about 6% of patients, while they were reported in one out of five men at time of diagnosis. Conversely, menstrual disorders appeared to be the (early) presenting complaint quite frequently, accounting for almost one in ten patients, while the prevalence of these disorders was estimated to be 16% at time of diagnosis. Headaches, due to GH hypersecretion and/or local tumor effects (also including visual defect) were highly prevalent at time of diagnosis and also the presenting complaint in about one third of the acromegaly patients. We further found that papillary thyroid cancer frequently led to the diagnosis of acromegaly, but this was based on only one small study including thirteen elderly acromegaly patients aged between 65 and 78 years [54]. Besides typical physical features, local tumor effects, menstrual disorders and galactorrhea, hypertension, carpal tunnel syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and hyperhidrosis, most of the presenting symptoms or comorbidities were only mentioned in one or two studies. Tseng et al. [56] also reported among those who presented with a specific symptom, sign or comorbidity, this feature eventually led to the diagnosis of acromegaly. Highest were: facial changes (99%), growth of hands and feet (98%), osteoarthritis (89%), sweaty and oily skin (86%), skin thickening (84%), deepening of the voice (82%), headache (80%), arthralgia (77%), excessive sweating (76%) and visual loss (76%). They also compared the age at the onset of features, and top 5 early symptoms were: galactorrhea (33 ± 9 years), amenorrhea (34 ± 10 years), sweaty and oily skin (37 ± 12 years), weight gain (38 ± 11 years) and headache (38 ± 12 years); while late symptoms or comorbidities were: carpal tunnel syndrome (42 ± 11 years), depressive syndrome (42 ± 14 years), arthralgia (43 ± 12 years), osteoarthritis (44 ± 11 years) and sleep apnea (45 ± 12 years). Our subanalysis also showed that the prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome was higher in older versus recent studies (25% versus 7%), which might reflect a more extensive clinical presentation due to more diagnostic delay, whilst differences in prevalence of the other mentioned late symptoms and comorbidities (depressive syndrome, arthralgia and sleep apnea) between the two groups were lacking. Shortening of diagnostic delay may also have led to the found decreased prevalence of various cardiovascular comorbidities in more recent versus older studies. Another explanation could be the general improvement of cardiovascular care over the last decades [57, 58].

It should be taken into consideration that the risk of bias for studies included in this systematic review was high. Selection bias was present in about half of the studies, mainly including (relatively) healthy acromegaly patients (no relevant comorbidities) and patients who were treated by surgical removal of the pituitary tumour. In approximately one out of three studies, the response rate was unclear. For most of the larger studies describing multiple symptoms and comorbidities, the method of measurement of these symptoms was unclear, just as it was unclear if they were measured in the same way for all patients (for instance: were symptoms only reported when patients complained about them, or were they actively asked for). Also, some clinical signs, symptoms or comorbidities were only reported in one or two studies, so no proper weighted mean prevalence could be calculated. We tried to focus on prevalent reported features in multiple studies.

Another limitation that should be taken into consideration is that in current systematic review, results of very heterogeneous studies concerning design (randomized controlled trials, both prospective and retrospective cohort and case–control studies), time period (1973–2021), sample size (6–3173) and geographical location are synthesized. This leads to differences in results and thereby to a wide range of reported prevalence. However, we have chosen this method to find information as complete as possible, and by calculating a weighted mean as well as performing subanalysis on study period, we tried to add more value to the reported prevalence. Also, our aim was to include only adults patients since the presentation of acromegaly is different in the pediatric population, but we made exceptions to fourteen studies whose age range started a few years before the age eighteen [9, 12, 28, 34, 52, 59–66]. These exceptions were made based on the age mean and standard deviation (or median and interquartile range), showing that the vast majority of included patients were adults. We believe that the findings in these populations may be relevant for our research question, taken into consideration the mean duration of the complaints before diagnosis.

The aim of current systematic review was to identify most prevalent clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities at time of diagnosis in acromegaly patients. Since systematic overviews are currently lacking, we are the first to report these features in a clear and scientifically based way. With the identification of these features, we can present a combination of complaints and comorbidities that should raise suspicion of acromegaly in both patients and medical caregivers more promptly. Future research should focus on bringing the current theoretical framework into practice: is it possible to detect patients at high risk of acromegaly by using this combination of clinical signs, symptoms and comorbidities? Ultimately this may shorten the diagnostic delay and improve quality of life and survival in patients with acromegaly, which is already found for cardiovascular comorbidities.

Other

The review protocol was preregistered and can be assessed at the PROSPERO register through ID CRD42022344505. Three amendments to the protocol were made: one about exclusion of articles that also include (some) participants younger than eighteen years old. The second amendment concerns the exclusion of the tertiary aim mentioned in the protocol (to identify visited healthcare providers before diagnosis of acromegaly/healthcare providers who first suspected or diagnosed acromegaly). We decided not to include this aim in our final manuscript, as we feel our search was not built to give an appropriate and valid answer to this question. Third, we added sub-analysis based on study period. Data extraction from included studies can be found in Online Appendix B.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

RV performed a systematic search in the bibliographic databases. TS and CB independently screened all articles. TS wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all tables and figures. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support was granted by Pfizer but the sponsor did not have any role in execution of the review.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Competing interests

There is no interest to declare.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Caron P, Brue T, Raverot G, Tabarin A, Cailleux A, Delemer B, et al. Signs and symptoms of acromegaly at diagnosis: the physician's and the patient's perspectives in the ACRO-POLIS study. Endocrine. 2019;63(1):120–129. doi: 10.1007/s12020-018-1764-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dekkers OM, Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Romijn JA, Vandenbroucke JP. Mortality in acromegaly: a metaanalysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(1):61–67. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esposito D, Ragnarsson O, Johannsson G, Olsson DS. Prolonged diagnostic delay in acromegaly is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Eur J Endocrinol. 2020;182(6):523–531. doi: 10.1530/EJE-20-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavrentaki A, Paluzzi A, Wass JA, Karavitaki N. Epidemiology of acromegaly: review of population studies. Pituitary. 2017;20(1):4–9. doi: 10.1007/s11102-016-0754-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabarro J. Acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol. 1987;26(4):481–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1987.tb00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon DA, Hill FM, Ezrin C. Acromegaly: a review of 100 cases. Can Med Assoc J. 1962;87(21):1106–1109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurel MH, Bruening PR, Rhodes C, Lomax KG. Patient perspectives on the impact of acromegaly: results from individual and group interviews. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:53–62. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S56740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Siegel S, Kleist B, Kohlmann J, Starz D, Buslei R, et al. Diagnosis and management of acromegaly: the patient's perspective. Pituitary. 2016;19(3):268–276. doi: 10.1007/s11102-015-0702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid TJ, Post KD, Bruce JN, Nabi Kanibir M, Reyes-Vidal CM, Freda PU. Features at diagnosis of 324 patients with acromegaly did not change from 1981 to 2006: acromegaly remains under-recognized and under-diagnosed. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;72(2):203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03626.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarool-Hassan R, Conaglen HM, Conaglen JV, Elston MS. Symptoms and signs of acromegaly: an ongoing need to raise awareness among healthcare practitioners. J Prim Health Care. 2016;8(2):157–163. doi: 10.1071/HC15033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrossians P, Daly AF, Natchev E, Maione L, Blijdorp K, Sahnoun-Fathallah M, et al. Acromegaly at diagnosis in 3173 patients from the Liège acromegaly survey (LAS) database. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2017;24(10):505–518. doi: 10.1530/ERC-17-0253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munn ZMS, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Munn Z, Falavigna M. Quality assessment of prevalence studies: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;127:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniel W. Biostatistics: A foundation for analysis in the health sciences. 7. New York: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naing LWT, Rusli BN. Practical issues in calculating the sample size for prevalence studies. Arch Orofac Sci. 2006;1(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhansali A, Kochhar R, Chawla YK, Reddy S, Dash RJ. Prevalence of colonic polyps is not increased in patients with acromegaly: analysis of 60 patients from India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(3):266–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dutta P, Hajela A, Pathak A, Bhansali A, Radotra BD, Vashishta RK, et al. Clinical profile and outcome of patients with acromegaly according to the 2014 consensus guidelines: impact of a multi-disciplinary team. Neurol India. 2015;63(3):360–368. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.158210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez B, Vargas G, Mendoza V, Nava M, Rojas M, Mercado M. The prevalence of colonic polyps in patients with acromegaly: a case-control, nested in a cohort colonoscopic study. Endocr Pract. 2017;23(5):594–599. doi: 10.4158/EP161724.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de los Espinosa MAL, Sosa-Eroza E, Gonzalez B, Mendoza V, Mercado M. Prevalence, clinical and biochemical spectrum, and treatment outcome of acromegaly with normal basal gh at diagnosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(10):3919–3924. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colao A, Pivonello R, Auriemma RS, Galdiero M, Ferone D, Minuto F, et al. The association of fasting insulin concentrations and colonic neoplasms in acromegaly: a colonoscopy-based study in 210 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3854–3860. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colao A, Pivonello R, Grasso LF, Auriemma RS, Galdiero M, Savastano S, et al. Determinants of cardiac disease in newly diagnosed patients with acromegaly: results of a 10 year survey study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(5):713–721. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berg C, Petersenn S, Walensi M, Möhlenkamp S, Bauer M, Lehmann N, et al. Cardiac risk in patients with treatment naïve, first-line medically controlled and first-line surgically cured acromegaly in comparison to matched data from the general population. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabet. 2013;121(2):125–132. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1314811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damjanovic SS, Neskovic AN, Petakov MS, Popovic V, Vujisic B, Petrovic M, et al. High output heart failure in patients with newly diagnosed acromegaly. Am J Med. 2002;112(8):610–616. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(02)01094-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dural M, Kabakcı G, Cınar N, Erbaş T, Canpolat U, Gürses KM, et al. Assessment of cardiac autonomic functions by heart rate recovery, heart rate variability and QT dynamicity parameters in patients with acromegaly. Pituitary. 2014;17(2):163–170. doi: 10.1007/s11102-013-0482-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo X, Gao L, Zhang S, Li Y, Wu Y, Fang L, et al. Cardiovascular system changes and related risk factors in acromegaly patients: a case-control study. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:573643. doi: 10.1155/2015/573643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iliaz R, Dogansen SC, Tanrikulu S, Yalin GY, Cavus B, Gulluoglu M, et al. Predictors of colonic pathologies in active acromegaly: single tertiary center experience. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2018;130(17):511–516. doi: 10.1007/s00508-018-1367-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matano Y, Okada T, Suzuki A, Yoneda T, Takeda Y, Mabuchi H. Risk of colorectal neoplasm in patients with acromegaly and its relationship with serum growth hormone levels. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(5):1154–1160. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Popielarz-Grygalewicz A, Stelmachowska-Banaś M, Gąsior JS, Grygalewicz P, Czubalska M, Zgliczyński W, et al. Subclinical left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with naive acromegaly - assessment with two-dimensional speckle-tracking echocardiography: retrospective study. Endokrynol Pol. 2020;71(3):227–234. doi: 10.5603/EP.a2020.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babic BB, Petakov MS, Djukic VB, Ognjanovic SI, Arsovic NA, Isailovic TV, et al. Conductive hearing loss in patients with active acromegaly. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27(6):865–870. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000201429.57746.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baldelli R, De Marinis L, Bianchi A, Pivonello R, Gasco V, Auriemma R, et al. Microalbuminuria in insulin sensitivity in patients with growth hormone-secreting pituitary tumor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):710–714. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bogazzi F, Nacci A, Campomori A, La Vela R, Rossi G, Lombardi M, et al. Analysis of voice in patients with untreated active acromegaly. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33(3):178–185. doi: 10.1007/BF03346578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colao A, Pivonello R, Spinelli L, Galderisi M, Auriemma RS, Galdiero M, et al. A retrospective analysis on biochemical parameters, cardiovascular risk and cardiomyopathy in elderly acromegalic patients. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007;30(6):497–506. doi: 10.1007/BF03346334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dal J, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Andersen M, Kristensen L, Laurberg P, Pedersen L, et al. Acromegaly incidence, prevalence, complications and long-term prognosis: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175(3):181–190. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herrmann BL, Wessendorf TE, Ajaj W, Kahlke S, Teschler H, Mann K. Effects of octreotide on sleep apnoea and tongue volume (magnetic resonance imaging) in patients with acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151(3):309–315. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1510309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hong AR, Kim JH, Kim SW, Kim SY, Shin CS. Trabecular bone score as a skeletal fragility index in acromegaly patients. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(3):1123–1129. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3344-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitale G, Galderisi M, Pivonello R, Spinelli L, Ciccarelli A, de Divitiis O, et al. Prevalence and determinants of left ventricular hypertrophy in acromegaly: impact of different methods of indexing left ventricular mass. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;60(3):343–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berker D, Tutuncu YA, Isik S, Aydin Y, Ozuguz U, Akbaba G, et al. Prevalence and recurrence rate of colonic lesions in acromegalic patients. Central Eur J Med. 2010;5(6):704–711. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamamoto M, Fukuoka H, Iguchi G, Matsumoto R, Takahashi M, Nishizawa H, et al. The prevalence and associated factors of colorectal neoplasms in acromegaly: a single center based study. Pituitary. 2015;18(3):343–351. doi: 10.1007/s11102-014-0580-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al-Futaisi A, Saif AY, Al-Zakwani I, Al-Qassabi S, Al-Riyami S, Wali Y. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of pituitary tumours using a web-based pituitary tumour registry in Oman. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2007;7(1):25–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szydełko J, Szydełko-Gorzkowicz M, Matyjaszek-Matuszek B. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios, and systemic immune-inflammation index as potential biomarkers of chronic inflammation in patients with newly diagnosed acromegaly: a single-centre study. J Clin Med. 2021;10(17):3997. doi: 10.3390/jcm10173997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan X, Chen X, Ge H, Zhu S, Lin Y, Kang D, et al. The change in distance between bilateral internal carotid arteries in acromegaly and its risk factors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020;11:429. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Akoglu G, Metin A, Emre S, Ersoy R, Cakir B. Cutaneous findings in patients with acromegaly. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2013;21(4):224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albarel F, Elaraki F, Delemer B. Daily life, needs and expectations of patients with acromegaly in France: An on-line survey. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2019;80(2):110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ando.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fukuda I, Hizuka N, Muraoka T, Kurimoto M, Yamakado Y, Takano K, et al. Clinical features and therapeutic outcomes of acromegaly during the recent 10 years in a single institution in Japan. Pituitary. 2014;17(1):90–95. doi: 10.1007/s11102-013-0472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giraldi EA, Veledar E, Oyesiku NM, Ioachimescu AG. Incidentally detected acromegaly: single-center study of surgically treated patients over 22 years. J Investig Med. 2021;69(2):351–357. doi: 10.1136/jim-2020-001605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ioachimescu AG, Handa T, Goswami N, Pappy AL, Veledar E, Oyesiku NM. Gender differences and temporal trends over two decades in acromegaly: a single center study in 112 patients. Endocrine. 2020;67:423–432. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-02123-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ganokroj P, Sunthornyothin S, Siwanuwatn R, Chantra K, Buranasupkajorn P, Suwanwalaikorn S, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in acromegaly, a retrospective single-center case series from thailand. Pan Afr Med J. 2021 doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.31.29920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jialal I, Nathoo BC, Joubert S, Asmal AC, Pillay NL. The clinical presentation and biochemical diagnosis of acromegaly and gigantism. S Afr Med J. 1982;61(17):617–620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keskin FE, Yetkin DO, Ozkaya HM, Haliloglu O, Sadri S, Gazioglu N, et al. The problem of unrecognized acromegaly: surgeries patients undergo prior to diagnosis of acromegaly. J Endocrinol Invest. 2015;38(6):695–700. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klijn JGM, Lamberts SWJ, de Jong FH, van Dongen KJ, Birkenhäger JC. Interrelationships between tumour size, age, plasma growth hormone and incidence of extrasellar extension in acromegalic patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 1980;95(3):289–297. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.0950289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nachtigall L, Delgado A, Swearingen B, Lee H, Zerikly R, Klibanski A. Changing patterns in diagnosis and therapy of acromegaly over two decades. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(6):2035–2041. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siegel S, Streetz van der Werf C, Schott JS, Nolte K, Karges W, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I. Diagnostic delay is associated with psychosocial impairment in acromegaly. Pituitary. 2013;16(4):507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11102-012-0447-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ceccato F, Barbot M, Lizzul L, Cuccarollo A, Selmin E, Merante Boschin I, et al. Clinical presentation and management of acromegaly in elderly patients. Hormones. 2021;20(1):143–150. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00235-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giorgis B, Campiche R, Burckhardt P, Gómez F. Diagnosis, treatment and course of hypophyseal tumors. Retrospective study of 123 cases. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1986;116(42):1431–1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tseng FY, Huang TS, Lin JD, Chen ST, Wang PW, Chen JF, et al. A registry of acromegaly patients and one year following up in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2019;118(10):1430–1437. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cuspidi C, Michey I, Meani S, Severgnini B, Fusi V, Salerno M, et al. Trends in hypertension control and left ventricular hypertrophy over three years. Ital Heart J. 2002;3(9):514–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arya KR, Krishna K, Chadda M. Skin manifestations of acromegaly - a study of 34 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1997;63(3):178–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banerji D, Das NK, Sharma S, Jindal Y, Jain VK, Behari S. Surgical management of acromegaly: long term functional outcome analysis and assessment of recurrent/residual disease. Asian J Neurosurg. 2016;11(3):261–267. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.145354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Khan SA, Ram N, Masood MQ. Patterns of abnormal glucose metabolism in acromegaly and impact of treatment modalities on glucose metabolism. Cureus. 2021;13(3):e13852. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Al Dahmani K, Afandi B, Elhouni A, Dinwal D, Philip J, et al. Clinical presentation, treatment, and outcome of acromegaly in the United Arab Emirates. Oman Med J. 2020;35(5):e172. doi: 10.5001/omj.2020.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.AlMalki MH, Ahmad MM, Buhary BM, Aljawair R, Alyamani A, Alhozali A, et al. Clinical features and therapeutic outcomes of patients with acromegaly in Saudi Arabia: a retrospective analysis. Hormones (Athens) 2020;19(3):377–383. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anagnostis P, Efstathiadou ZA, Polyzos SA, Adamidou F, Slavakis A, Sapranidis M, et al. Acromegaly: presentation, morbidity and treatment outcomes at a single centre. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(8):896–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Portocarrero-Ortiz LA, Vergara-Lopez A, Vidrio-Velazquez M, Uribe-Diaz AM, García-Dominguez A, Reza-Albarrán AA, et al. The Mexican acromegaly registry: clinical and biochemical characteristics at diagnosis and therapeutic outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):3997–4004. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Voit D, Saeger W, Lüdecke DK. Pituitary adenomas in acromegaly: comparison of different adenoma types with clinical data. Endocr Pathol. 1999;10(2):123–135. doi: 10.1007/BF02739824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stovner LJ, Andree C. Prevalence of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain. 2010;11(4):289–299. doi: 10.1007/s10194-010-0217-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stovner L, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Augustin M, Radtke M, Herberger K, Kornek T, Heigel H, Schaefer I. Prevalence and disease burden of hyperhidrosis in the adult population. Dermatology. 2013;227(1):10–13. doi: 10.1159/000351292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ribeiro SMM, Betanho MR, Lopes RAC, Guimarães RLP, dos Santos CB, Junior JCBS. Primary hyperhidrosis prevalence and characteristics among medical students in Rio de Janeiro. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(9):e0220664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0220664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Avcu N, Kanli A. The prevalence of tongue lesions in 5150 Turkish dental outpatients. Oral Dis. 2003;9(4):188–195. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2003.02933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patil S, Kaswan S, Rahman F, Doni B. Prevalence of tongue lesions in the Indian population. J Clin Exp Dent. 2013;5(3):e128. doi: 10.4317/jced.51102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Van’t Leven M, Zielhuis GA, van der Meer JW, Verbeek AL, Bleijenberg G. Fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome-like complaints in the general population. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20(3):251–257. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lewis G, Wessely S. The epidemiology of fatigue: more questions than answers. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46(2):92–97. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.2.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.van der Ende MY, Siland JE, Snieder H, van der Harst P, Rienstra M. Population-based values and abnormalities of the electrocardiogram in the general Dutch population: the lifelines cohort study. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(10):865–872. doi: 10.1002/clc.22737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu Y, Xu K, Wu S, Qin M, Liu X. Value of estimated pulse wave velocity to identify left ventricular hypertrophy prevalence: insights from a general population. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12872-022-02541-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Savage DD, Garrison R, Kannel W, Levy D, Anderson S, Jr Stokes J, et al. The spectrum of left ventricular hypertrophy in a general population sample: the Framingham Study. Circulation. 1987;75(1 Pt 2):I26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Redfield MM, Jacobsen SJ, Burnett JC, Mahoney DW, Bailey KR, Rodeheffer RJ. Burden of systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction in the community: appreciating the scope of the heart failure epidemic. JAMA. 2003;289(2):194–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wan S-H, Vogel MW, Chen HH. Pre-clinical diastolic dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(5):407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, He J. Worldwide prevalence of hypertension: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2004;22(1):11–19. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Zon SK, Amick BC, III, de Jong T, Brouwer S, Bültmann U. Occupational distribution of metabolic syndrome prevalence and incidence differs by sex and is not explained by age and health behavior: results from 75 000 Dutch workers from 40 occupational groups. BMJ Open Diabet Res Care. 2020;8(1):e001436. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2020-001436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Azizi F, Salehi P, Etemadi A, Zahedi-Asl S. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in an urban population: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2003;61(1):29–37. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(03)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Márquez-Sandoval F, Macedo-Ojeda G, Viramontes-Hörner D, Fernández Ballart JD, Salas Salvadó J, Vizmanos B. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Latin America: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(10):1702–1713. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Buckland G, Salas-Salvadó J, Roure E, Bulló M, Serra-Majem L. Sociodemographic risk factors associated with metabolic syndrome in a Mediterranean population. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(12):1372–1378. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008003492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.van den Berg EH, Amini M, Schreuder TC, Dullaart RP, Faber KN, Alizadeh BZ, et al. Prevalence and determinants of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in lifelines: a large Dutch population cohort. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2):e0171502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khan MAB, Hashim MJ, King JK, Govender RD, Mustafa H, Al KJ. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes–global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J Epidemiol Global Health. 2020;10(1):107. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.191028.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Picavet H, Schouten J. Musculoskeletal pain in the Netherlands: prevalences, consequences and risk groups, the DMC3-study. Pain. 2003;102(1–2):167–178. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kerkhof GA. Epidemiology of sleep and sleep disorders in The Netherlands. Sleep Med. 2017;30:229–239. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Senaratna CV, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Campbell BE, Matheson MC, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vuik FE, Nieuwenburg SA, Moen S, Schreuders EH, Pool MDO, Peterse EF, et al. Population-based prevalence of gastrointestinal abnormalities at colon capsule endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;20(3):692–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pan J, Cen L, Xu L, Miao M, Li Y, Yu C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for colorectal polyps in a Chinese population: a retrospective study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):6974. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63827-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jayadevan R, Anithadevi T, Venugopalan S. Prevalence of colorectal polyps: a retrospective study to determine the cut-off age for screening. Gastroenterol Pancreatol Liver Disord. 2016;3(2):1–5. doi: 10.15226/2374-815X/3/2/00156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.González-González J, Maldonado-Garza H, Flores-Rendón R, Garza-Galindo A. Risk factors for colorectal polyps in a Mexican population [Corrected and republished] Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2010;2(75):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Løberg M, Zauber AG, Regula J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Population-based colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):894–902. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lemmens V, Steenbergen LV, Janssen-Heijnen M, Martijn H, Rutten H, Coebergh JW. Trends in colorectal cancer in the south of the Netherlands 1975–2007: rectal cancer survival levels with colon cancer survival. Acta Oncol. 2010;49(6):784–796. doi: 10.3109/02841861003733713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wong MCS, Huang J, Huang JLW, Pang TWY, Choi P, Wang J, et al. Global prevalence of colorectal neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(3):553–61.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Häussler B, Gothe H, Göl D, Glaeske G, Pientka L, Felsenberg D. Epidemiology, treatment and costs of osteoporosis in Germany—the BoneEVA Study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(1):77–84. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Salari N, Ghasemi H, Mohammadi L, Behzadi Mh, Rabieenia E, Shohaimi S, et al. The global prevalence of osteoporosis in the world: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16(1):609. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02772-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Reiners C, Wegscheider K, Schicha H, Theissen P, Vaupel R, Wrbitzky R, et al. Prevalence of thyroid disorders in the working population of Germany: ultrasonography screening in 96,278 unselected employees. Thyroid. 2004;14(11):926–932. doi: 10.1089/thy.2004.14.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mu C, Ming X, Tian Y, Liu Y, Yao M, Ni Y, et al. Mapping global epidemiology of thyroid nodules among general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1029926. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.1029926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nederlandse Kanker Registratie (NKR) Cijfers. [cited 2022 July 27th]. Available from: https://nkrcijfers.iknl.nl/#/viewer/fac1d6c3-d784-498f-9838-8244804d5023

- 104.Zheng R, Zeng H, Zhang S, Chen T, Chen W. National estimates of cancer prevalence in China, 2011. Cancer Lett. 2016;370(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Feldman AR, Kessler L, Myers MH, Naughton MD. The prevalence of cancer. N Engl J Med. 1986;315(22):1394–1397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198611273152206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Trimbos-instituut. [cited 2022 July 27th]. Available from: https://www.trimbos.nl/kennis/cijfers/depressie/.

- 107.Lim GY, Tam WW, Lu Y, Ho CS, Zhang MW, Ho RC. Prevalence of depression in the community from 30 countries between 1994 and 2014. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):2861. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Svensson A, Ofenloch R, Bruze M, Naldi L, Cazzaniga S, Elsner P, et al. Prevalence of skin disease in a population-based sample of adults from five European countries. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1111–1118. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. The Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, Ornstein E, Ranstam J, Rosén I. Prevalence of carpal tunnel syndrome in a general population. JAMA. 1999;282(2):153–158. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.2.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hashimoto S, Ikegami S, Nishimura H, Uchiyama S, Takahashi J, Kato H. Prevalence and risk factors of carpal tunnel syndrome in Japanese aged 50 to 89 years. J Hand Surg. 2020;25(03):320–327. doi: 10.1142/S2424835520500356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Habib KR. Estimation of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) prevalence in adult population in western European countries: a systematic review. Eur J Clin Biomed Sci. 2017;3(1):13–18. doi: 10.11648/j.ejcbs.20170301.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lyberg-Åhlander V, Rydell R, Fredlund P, Magnusson C, Wilén S. Prevalence of voice disorders in the general population, based on the Stockholm public health cohort. J Voice. 2019;33(6):900–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.de Araújo PL, Espelt A, Balata PMM, de Lima KC. Prevalence of voice disorders in the elderly: a systematic review of population-based studies. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(10):2601–2609. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3252-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.