ABSTRACT.

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease caused by Leishmania parasites. Meglumine antimoniate, or Glucantime, is the primary drug used to treat this disease. Glucantime with a standard painful injection administration route has high aqueous solubility, burst release, a significant tendency to cross into aqueous medium, rapid clearance from the body, and insufficient residence time at the injury site. Topical delivery of Glucantime can be a favorable option in the treatment of localized cutaneous leishmaniasis. In this study, a suitable transdermal formulation in the form of nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC)-based hydrogel containing Glucantime was prepared. In vitro drug release studies confirmed controllable drug release behavior for hydrogel formulation. An in vivo permeation study on healthy BALB/C female mice confirmed appropriate penetration of hydrogel into the skin and sufficient residence time in the skin. In vivo performance of the new topical formulation on the BALB/C female mice showed a significant improvement in reduction of leishmaniasis wound size, lowering parasites number in lesions, liver, and spleen compared with commercial ampule. Hematological analysis showed a significant reduction of the drug’s side effects, including variance of enzymes and blood factors. NLC-based hydrogel formulation is proposed as a new topical administration to replace the commercial ampule.

INTRODUCTION

Leishmaniasis is a tropical and subtropical disease caused by an intracellular parasite transmitted to humans by the bite of a sand fly and has high morbidity and mortality.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis, the most common form of leishmaniasis, causes skin sores. Visceral leishmaniasis affects several internal organs, usually the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, with symptoms such as high fever, weight loss, enlarged liver and spleen, anemia, weakness, and dark skin.3–5 Meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime), an antimonial compound with the final molecular formulation of C7H18NO8Sb that is produced by the reaction of pentavalent antimony (SbV) with N-methyl-D-glucamine as a carbohydrate derivative, is the main choice for the leishmaniasis treatment.6–8 Glucantime is often given to patients by direct injection into the wound, which is painful, particularly for children.9 Because of its high aqueous solubility (> 300 mg/mL), Glucantime has a burst release profile, a significant tendency to cross into the aqueous medium followed by rapid clearance from the body, insufficient residence time in the skin at the site of injury, and high systemic drug absorption.10 Thus it is often necessary to increase the frequency of administration, leading to higher costs and more harmful side effects, including variance of enzymes and blood factors, fever, nausea and vomiting, acute renal and hepatic failure, skin rash, arthralgia, severe inflammation at the injection site, and toxic side effects on vital organs such as liver, spleen, kidney, heart, and pancreas.5–7,9,11,12 The challenge of an explosive release profile and its consequences can be eliminated by encapsulating the drug in a nanocarrier formulation, and the problem of painful injection of the drug can be solved by changing the method of drug administration to the external usage form. Furthermore, because of no direct entry of the drug into the bloodstream, transdermal administration can also significantly eliminate treatment problems and reduce harmful side effects on other organs of the body. Other advantages of this administration route include maintaining a steady plasma level of the drug, lower toxicity, and ease of administration.13 In this regard, applying drug nanocarriers with the ability to convert to a product with the topical administration route is suggested.

Nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) is one of the best nanoparticles (NPs) for drug delivery, with the ability to encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs and easy usage in topical formulation.14–17 In addition to low toxicity, appropriate biodegradation and biocompatibility, drug protection, high drug loading efficiency, fine particle size, controlled drug release, lower drug leakage, and avoidance of organic solvents in production, NLCs can more strongly immobilize drugs and prevent particles from coalescing by the solid matrix compared with emulsions.15

The components of NLC include liquid lipids, solid lipids, surfactants, and deionized water.14 Lipids are biocompatible and biodegradable compounds (e.g., a variety of fatty acids and herbal oils) with high drug-loading capacity and appropriate molecule size to achieve the small size of NPs. One of the best topical formulations is hydrogel, a three-dimensional (3D) network of hydrophilic polymers (e.g., various types of carbomer). Applied polymers for the hydrogel preparation can swell in water and hold a large amount of fluid while maintaining their structure due to chemical or physical cross-linking of individual polymer chains.18 The large amount of water in a hydrogel structure improves penetration of the drug through the skin.

Recently, a hydrogel formulation based on NLC was introduced as a possible semisolid system for the topical and transdermal drug administration routes. This system is made up of a hydrogel-based vehicle in which drug-loaded NLCs are dispersed and entrapped in the network.19 Glucantime has not previously been encapsulated in an NLC nanocarrier. However, some research has investigated liposome20,21 and chitosan/clay NPs12 for Glucantime encapsulation for topical use. However, these studies did not examine the therapeutic impact of manufactured nanostructures or compare them with the commercial ampule.

In the present work, NLC-based hydrogel for encapsulation of Glucantime was studied for the first time. The physicochemical properties of NLC and hydrogel samples were examined, and the success of hydrogel formulation to penetrate the skin was investigated in healthy BALB/C female mice. In vivo performance of a new hydrogel formulation and commercial ampule was then evaluated on the injured BALB/C female mice to evaluate the success of the new topical formulation in the leishmaniasis treatment. In this regard, the wound size, relevant hematological features, skin allergies, and parasite load in the wound, liver, and spleen were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Oleic Acid (PubChem CID:5312955), glycerol monostearate (GMS) (PubChem CID:24699), Tween 80 (PubChem CID:86289060), Span 80 (PubChem CID: 9920342), ethanol (PubChem CID: 702), carbomer 940 (PubChem CID: 91824753), triethanolamine (PubChem CID: 7618), phosphotungstic acid (PubChem CID: 71308707), phosphate-buffered saline (PubChem CID: 24978514), fetal bovine serum (PubChem CID: 1412328), penicillin (PubChem CID: 5904), streptomycin (PubChem CID: 19649), and methanol (PubChem CID: 887) were purchased from Merck (Germany). Glucantime (PubChem CID:64953) powder was purchased from Sanofi (Paris, France), and Glucantime commercial ampule (Sanofi) was bought from Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. All chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade.

NLC sample preparation method.

Preparation of lipid nanostructures was performed based on the double emulsion method, which is a suitable technique for the encapsulation of hydrophilic active pharmaceutical ingredients in the NLCs.22,23 First, 0.3 g of GMS as solid lipid and 0.09 g of oleic acid as liquid lipid were mixed with 0.055 g of Span 80 as lipid phase surfactant and 0.09 g of ethanol as an organic solvent for improved dispersion. Considering the melting temperature of solid lipid (approximately 65°C), this mixture was placed in an 80°C water bath. To avoid aggregation during preparation without heating, a temperature slightly above lipid melting point was used. Next, 1.5 mL of deionized water containing 0.1 g of Glucantime was used as the internal aqueous phase at 80°C. The external water phase containing 5 mL of deionized water and 0.275 g of Tween 80 was prepared and placed at the same temperature. The lipid phase was homogenized using an ultrasonic probe at 80 W at the cycle of 1 for 5 minutes, and then the internal and external water phases were added, respectively, at 2-minute intervals. After 5 minutes of ultrasonic homogenization, 40 mL of cold water cooled the sample to 0 to 2°C. It was then agitated at 100 rpm on the magnetic stirrer for 10 minutes at room temperature to ensure homogeneity and remove the organic solvent.17,24,25 The hydrogel formulation was made based on this sample and freeze-dried at a temperature of −70°C for 24 hours for further characterization analysis.

Hydrogel sample preparation method.

Carbomer 940, as an applicable cellulose derivative and the gelling agent, was selected for hydrogel formation. This compound has the advantages of low price, safety in topical use, and simple preparation that does not require neutralization or extensive preparation time. Carbomer 940 hydrogels have also shown suitability for NP incorporation19 and demonstrated positive effects on wound healing and can help treat leishmaniasis lesions.26

To prepare a hydrogel formulation based on the NLC sample, three different weight percentages of carbomer 940 were dissolved in 2 g of distilled water to prepare solutions with a weight percentage of 0.3, 0.6, and 0.9, respectively. These were agitated under moderate stirring at 100 rpm for 3 hours. Then, 10 g of NLC formulation were added to the mixture drop-wise under magnetic stirring at 100 rpm. After 30 minutes, the obtained sample was neutralized to pH 6.5 to 7.0 using 0.5 mL of triethanolamine under gentle rotation on a magnetic stirrer for more compatibility with the skin of the body through topical administration. Finally, the hydrogel sample was left at rest at a temperature of 2 to 8 for 30 minutes to achieve uniformity and greater strength.27,28 Characterization analysis was performed to select the best carbomer percentage for further in vitro and in vivo investigations.

Characterization of NLCs.

Average particle size and zeta potential.

The particle size, and zeta potential of the prepared lipid NPs were determined by Zetasizer (Malvern Instrument Ltd., Worcestershire, United Kingdom) based on the dynamic light scattering technique (DLS) at the temperature of 25°C. The NLC sample was diluted with a ratio of 1:100 for DLS analysis. Analysis was repeated three times for each sample.

Transmission electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy analysis.

At the first step in preparing a transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis sample, 2 mg of the dried sample was dispersed in 600 μL of water and was continuously stirred by the magnetic stirrer at 50 rpm for 5 minutes and sonicated for 2 minutes. After adding 250 μL of 90%wt ethanol, the sample was agitated at 50 rpm for 3 minutes to remove the lipid layer that prevented TEM imaging. The obtained sample was diluted 50 times with water, deposited on film-coated copper grids, stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid for 2 minutes, washed with water, and dried at room temperature for 12 hours. TEM (Leo 912 AB, American) was used to assess the morphology of NPs.29,30

An atomic force microscopy (AFM) analyzer detected sample surface attributes (Brisk model Ara Pazhoohesh, Tehran, Iran). This analysis also was performed on dried formulation, and the steps for sample preparation were similar to the TEM preparation method.

Differential scanning calorimetry analysis.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was used to measure heat loss from physical or chemical changes within a sample as a function of the temperature. It also allowed the study of the melting and crystallization behavior of crystalline materials like lipid NPs. In the case of NLC, DSC experiments were practical in understanding the mixing behavior of solid fat with liquid oil.24 In this regard, the thermal property of Glucantime, unloaded NLC, and loaded NLC were investigated using DSC (Diamond DSC, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA). The lyophilized and frozen NLC samples at −80°C by freeze-drying steps similar to TEM analysis were applied for this analysis. All three samples were heated at a rate of 5°C/minute from 25 to 300°C.30

Functional groups and crystallinity of structures.

Glucantime and unloaded and loaded NLC samples, dried using similar steps as in the TEM sample preparation, were analyzed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR; Thermo Nicolet, American), which scans the samples with infrared light to determine the chemical bonds and verify the presence of all materials inside the NLC.

The x-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Bruker D8 Advance, Bruker, Mannheim, Germany) was performed by wide-angle x-ray scattering with a scan speed of 2°/minute, in the range of 6° to 80°. The x-ray source was a 2.2 kW Cu anode (40 kV, 40 mA, Cu-Kα radiation, λ = 0.15406 nm). Before the measurement, the unloaded and loaded NLC samples were lyophilized and frozen at −80°C by freeze-drying steps similar to TEM analysis. The bulk lipid was analyzed without pretreatment.24

Drug entrapment efficiency and drug loading content.

To determine drug entrapment efficiency (EE), 5 mL of each sample was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 minutes at room temperature. The supernatant solution was then transferred from the 0.22-µm filter.7,31 The solution was transferred to the ICP-OES apparatus (Arcos, Germany) after being diluted with deionized water in a 1:10 ratio to determine the amount of antimony in the sample. The unloaded Glucantime content was then determined using stoichiometric relationships, and the drug entrapment efficiency percentage (EE%) and loading content percentage (LC%) were computed using Equations (1) and (2)7:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Physicochemical characterization of hydrogel.

Macroscopic analysis and pH determination.

The macroscopic characteristics of hydrogels were observed about the normality of aspect as a sign of agglomeration, nonuniformity of dispersion, and color abnormality.32 In addition, to measure the pH value, 2.5 g of hydrogel sample was dispersed in 25 mL of distilled water to achieve the concentration of 10% w/v.32 The pH of the diluted gel was accurately determined by a pH meter (Ciba Corning Diagnostics, Sudbury, United Kingdom) at ambient temperature.

Average particle size and stability over storage time.

A hydrogel sample (0.1 g) was diluted with water up to 50 mL to determine the droplet size of hydrogel formulation using Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, United Kingdom) based on DLS. Each sample’s preparation and measurement were repeated three times. The ability of the nanocarrier to retain the drug was evaluated by storing the hydrogel formulation for 6 months at three temperatures: 4 to 5°C (refrigerator), 25 ± 2°C (room temperature), and 40°C.32 The hydrogel samples were stored in tightly sealed vials (5-mL capacity). Particle size and drug content were determined using the methods outlined in the particle size and drug entrapment investigations, respectively. As instability metrics, agglomeration as particle size increasing, drug leakage as loss in entrapment efficiency, color change, phase separation, and any physical instability were evaluated.28,33

Functional groups and crystallinity of structures.

FTIR analysis was applied to dried base hydrogel (containing water and gelling agent), dried unloaded NLC-based hydrogel, and dried loaded NLC-based hydrogel formulations (Nicolet, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

XRD analysis (Bruker D8 Advance) on dried base hydrogel containing water and gelling agent, dried unloaded NLC-based hydrogel, and dried loaded NLC-based hydrogel formulations was performed.

Rheological investigations of hydrogels.

Swelling.

Hydrogels are three-dimensional cross-linked hydrophilic polymers that may swell in water without dissolving. With the aim of selecting the best gelling agent percentage, the swelling profile was evaluated for three hydrogel formulations containing different gelling agent percentages. In this regard, the hydrogel samples were dried for 24 hours in a freeze-dryer, and their dry mass was determined (Md). After that, the dried sample was submerged in distilled water for up to 15 hours. Samples were withdrawn from the watery medium at different time intervals, their excess water was collected with filter paper, and their swollen mass was measured (Ms). Finally, the swelling rate was estimated using Equation (3)12,34:

| (3) |

Viscosity.

The viscosity study of hydrogels was carried out at 25 ± 2°C using a rotational viscometer (LVDV-II+ Pro, Brookfield Engineering, Middleboro, MA), spindle SC4-25 with a small sample adapter. The viscosity value was evaluated for three hydrogel formulations containing different gelling agent percentages as 0.3%wt, 0.6%wt, and 0.9%wt. To determine the rheological behavior of each formulation, the viscosity curve was plotted (20 points with the shear interval of 0.05/s). After that, different mathematical flow models were fitted to the points, and the best one was reported.28,32

Spreadability.

Hydrogel should spread easily without too much drag force and not produce greater friction in the rubbing process.35 In the other words, spreadability is an essential property of topical formulation.19 It was evaluated according to the parallel plate method.32 This method uses a circular glass mold plate (diameter = 20 cm, width = 0.2 cm) with a central orifice of 1 cm in diameter, which is placed on a glass support plate (20 cm × 20 cm) positioned over a millimeter graph paper.36 The sample was introduced into the orifice and the surface level with a spatula. The plaque mold was carefully removed, and a glass plate of known weight was placed over the sample for its pressing. After 1 minute, the spreading areas covered by the sample were measured in millimeters in vertical and horizontal axes at ambient temperature with the aid of the graph paper scale. Subsequently, the average diameter and circular spreading area were calculated. The spreadability factor (Sf) was also calculated by Equation (4):

| (4) |

in which Sf (mm2.g−1) is the spreadability factor, A (mm2) is the maximum spread area after the addition of the sequence of glass plates of known weights W (g). The spreading area was plotted against the plate weights to obtain the spreading profile.32

In vitro drug release.

Franz diffusion cell and dialysis bag methods were applied to study the drug release from hydrogel and commercial ampule, respectively. For the hydrogel drug release study, the diffusion cell was fitted with a 0.45-μm cellulose acetate membrane. First, the membrane was hydrated in distilled water for 24 hours at 25°C. It was then placed between receptor and donor of the cell. The diffusion medium was 25 mL of phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4 corresponded to the pH of the blood environment), which was filled into the receptor. The diffusion medium was continuously stirred by the magnetic stirrer at 70 rpm. After that, 2 g of the Glucantime hydrogel sample containing 4 mg of the drug was accurately weighed and deposited on the membrane in the donor compartment. One milliliter of the sample was removed from the receptor compartment at 0.5-, 1-, 2-, 4-, 6-, 8-, 12-, 24-, 48-, and 72-hour intervals to evaluate the drug content and replaced immediately with an equal volume of fresh receptor medium after each sampling. The drug concentration in withdrawn samples was evaluated using the ICP-OES apparatus (Arcos), as previously described. The data were shown as a percentage of medication release versus time. The drug content retrieved at each sampling interval was added to the next dose, and the medication’s cumulative effect was considered in calculations.20,37,38

To compare the drug release profile of the commercial ampule with that of the hydrogel, 2 mL of diluted commercial ampule solution with a drug concentration of 2 mg/mL was placed in cellulose acetate dialysis bags (12 kDa), which were then floated in 20 mL of PBS medium at pH = 7.4 for 72 hours on an incubator shaker at 37°C and 70 rpm. After 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours, 1 mL of each sample was removed from the medium to determine the drug content and promptly reintroduced with an equivalent volume of fresh buffer. As previously stated, samples were transported to ICP-OES analysis for detecting the drug content, and the release profile was performed as described previously.7,30,39 In the final step, fitting the obtained release profile of the two therapeutic formulations, including commercial ampule and NLC-based hydrogel, with different mathematical models, was investigated, and the diffusion behavior of each sample was evaluated. Zero-order, first-order, Hixson–Crowell, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer–Peppas models were applied for this aim.40

In vivo studies.

Parasites culture.

L. major (MRHO/IR/75/ER) was kindly prepared by the parasitology laboratory of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. Parasites were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium and supplemented with fetal bovine serum, penicillin (200 IU/mL), and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 25 ± 1°C. After 4 days of incubation, the cultures were passaged and the growth of promastigotes was daily monitored.7,41

Antipromastigote assay.

To investigate the antipromastigote performance of the new NLC formulation on Leishmania major parasites by direct-counting assay, 24-well tissue culture plates were used. Briefly, 180 µL of the promastigote solution with a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/mL was added to a 24-well tissue culture plate. Then, four groups were considered:

Group 1 received loaded-NLC sample with the drug concentration of 2 mg/mL,

Group 2 received a mixture of unloaded NLC sample and Carbomer 940 (components of unloaded NLC-based hydrogel),

Group 3 received the diluted commercial ampule with the drug concentration of 2 mg/mL, and

Group 4 was a control group that received no treatment.

For each group, six wells were assigned to repeat the experiment six times.

In this regard, 100 µL of each sample was added to each well and incubated at 25°C for 72 hours. After fixing by methanol, all the samples were stained with Giemsa to determine the number of promastigotes by the light microscopy and evaluated after 24, 48, and 72 hours.7,42,43

Animals.

Twenty-six BALB/C female mice, 6 to 8 weeks old, with a body weight of ∼20 g, were kindly provided by the Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute, North East Branch, Mashhad, Iran. The mice were housed in plastic cages with an air-conditioned room under a constant 12:12 hour light–dark cycle with controlled humidity (50–60%) and free access to food and water. With the aim of protecting the animals from pain and discomfort, experiments were carried out according to an ethical protocol.

Permeation study from healthy mouse skin.

To determine the amount of penetrated drug, 1 g of hydrogel sample containing Glucantime was placed on the top of mice tails. After 6 hours, 1 mL of metabolized blood around its heart was sampled and analyzed by ICP-OES to determine the transferred drug into the bloodstream. After collecting the remaining hydrogel sample on the skin surface with a spatula and detecting its drug amount by ICP-OES analysis, the entire dosing area was collected with a biopsy punch to detect the drug retained in the mice’s skin layers. The skin layers were minced and heated in the presence of 250 μL of PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 minutes at 60°C. Then, 250 μL of deionized water was added to the sample to dissolve the drug. The obtained sample was then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min. To measure the amount of drug retained in the skin, the supernatant was collected and analyzed using the ICP-OES method described previously.20,44

Infecting and therapy method.

The animals were inoculated subcutaneously at the base of the tail with approximately 2 × 106 (cells/mL) L. major promastigotes. Over time, when a local lesion appeared and the presence of leishmania protozoa was confirmed by parasitological examinations, mice were randomly divided into three groups:

Group 1 received the commercial ampule,

Group 2 received NLC-based hydrogel formulation, and

Group 3 was a control group without any treatment.

In the first group, the commercial ampule was injected subcutaneously in and around the lesion site with 2 mg of the drug in each administration twice a week for 30 days. The treatment process in the second group was topical administration of hydrogel sample containing 2 mg of Glucantime in 1 g of the sample so that every mouse received 2 g of hydrogel during a week with the frequency of twice a day until 30 days, considering that the mice had almost similar weight. Furthermore, the volume injected in and around the lesion site or the hydrogel amount rubbed on the wound surface was enough to support the entire wound site.41,43

Measuring the wound size.

Before and after the treatment, the diameter of lesions in two dimensions (D and d) at right angles to each other was measured using a vernier caliper and the size (in millimeters) was determined according to Equation (5).43

| (5) |

Microscopical examinations of lesions.

The parasite numbers comparison among the wound of the three studied groups can investigate the antileishmanial therapeutic effects of various formulations. Laboratory demonstration of the parasite number in the lesions as the microscopical examination was performed by making stained smears. In this regard, all lesions were cleaned with ethanol and punctured at the margins with a sterile lancet, and exudate was smeared. After drying in the air and fixing with methanol, the smears were stained with Giemsa to determine the number of parasites by light microscopy.41

Microscopical examinations of the liver and spleen.

The microscopical investigation of the liver and spleen is essential to determine the probability of visceral leishmaniasis. To perform this, the parasite number in smeared samples of these organs was counted. For this purpose, a small and thin layer of the liver and spleen was collected using a biopsy punch, and after pigmentation, the sections were fixed in 5% cacodylate-buffered formalin (pH = 7.4). Then, 2-µm sections were cut and stained with Giemsa to determine the parasites number using light microscopy.45

Symptoms of skin allergies.

External side effects, including symptoms of skin allergies such as redness of the skin, skin inflammation, and discharge of infection, were evaluated in all mice during and after treatment.

Hematological studies.

To investigate the side effects of formulations on internal organs, blood work including complete blood count (CBC) analysis, liver enzymes, bilirubin as a criterion of liver inflammation, and alkaline phosphatase as the most vital criterion of severe infection were evaluated. An appropriate needle was used for blood sample collection with or without thoracotomy. Blood samples were taken from the heart, preferably from the ventricle, slowly to avoid collapsing of the heart.46 After pouring the blood sample into the appropriate vials, for some analyses, the blood sample was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 minutes to separate its plasma and serum.

Statistical analysis.

After measuring all in vivo characteristics, the significance of the difference between them in each group during the treatment period and between different groups was determined by statistical analysis. Data analysis was carried out using the SPSS statistical package (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY), version 26.0. Differences between the test and control groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance and Tukey test. In addition, a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To investigate the mortality of mice in different groups, the probability of survival versus time in all groups were evaluated by PRISM software version 9.4.1.681.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of NLC.

On the basis of the DLS analysis, the NLC sample had tiny droplets with an average particle size of 93.87 ± 0.1 nm and a polydispersity index (PDI) value of 0.295 ± 0.015, indicating uniform size distribution (Figure 1A). Moreover, this sample had an acceptable zeta potential value equal to −30.31 ± 0.25 mV, which confirms proper stability and ability to prevent particle agglomeration in a short time. This sample also had high entrapment efficiency and drug-loading content of 74 ± 0.37% and 19 ± 0.21%, respectively.

Figure 1.

(A) Dynamic light scattering graph, (B) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image, (C) TEM size histogram, (D) two-dimensional atomic force microscopy (AFM) image, (E) three-dimensional AFM image, and (F) differential scanning calorimetry diagram of drug, loaded nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) and unloaded NLC samples.

As the TEM image in Figure 1B illustrates, NLC particles have a spherical structure with an average particle size of 100 nm, similar to the measured particle size by DLS analysis. The histogram of particle size based on TEM analysis indicates that the most significant part of particles has droplet size in the range of 80 to 100 nm (Figure 1C). As shown in Figure 1D, the two-dimensional image of AFM analysis indicates the uniformity and reasonable distribution of NPs. In Figure 1E, as a 3D AFM image, the similarity of the height of peaks illustrates uniformity in particle size over the sample.

In Figure 1F, the DSC curves of glucantime, unloaded and loaded NLC formulations are reported. Both unloaded and loaded NLC formulations exposed an endothermic peak at 53.9°C related to the melting point of GMS as solid lipid (57–65°C).47 The DSC graph of Glucantime exposed a sharp exothermic peak at 264°C due to the bond-breaking process at a high temperature, which has not apparent in the loaded NLC formulation. It indicates the successful molecular dissolution and loading of Glucantime in the NLC formulation.48

Physicochemical characterization of hydrogel.

Macroscopic analysis and pH determination.

All formulations showed brilliant, homogenous aspects and were white in color, similar to gel-cream formulation, with an odor characteristic of oil. The pH values of NLC-based hydrogels was 6.75 ± 0.03 and thus compatible with topical applications and near to that of skin, the epidermis of which is slightly acidic.32,42,49

Average particle size and stability studies.

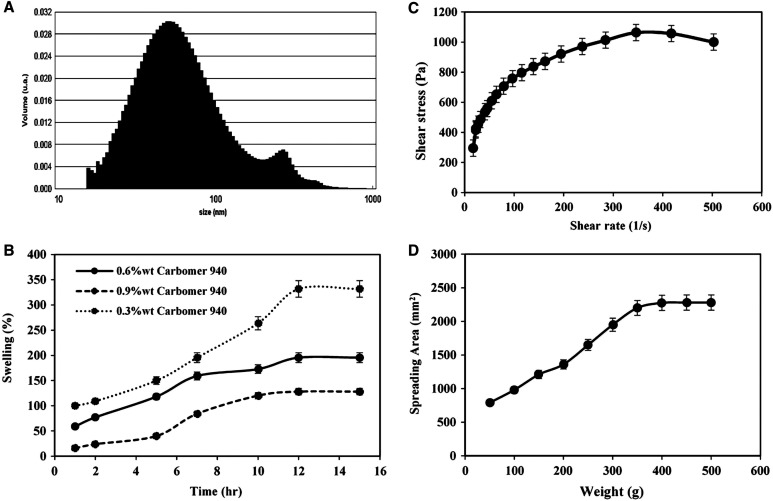

Thermal stability experiments for produced hydrogel samples were performed at 4, 25, and 40°C. On the basis of the results, no physical instabilities such as color change or phase separation were found. Table 1 shows the characterization data for the loaded-NLC based hydrogel sample, which include the average particle size, PDI, and EE% at the preparation time and after 3 and 6 months for three temperatures. As seen in Table 1, the average particle size of the hydrogel sample increased somewhat during storage. Because particles tend to agglomerate at lower temperatures, particle size increases at lower temperatures. Drug leakage was minimized at lower temperatures due to drug immobilization and lack of inclination to detach from the nanostructure. At high temperatures, drug leakage was increased greatly, and the encapsulation efficiency was significantly decreased. In all three storage temperatures, the PDI values did not change much over time. A DLS diagram of the prepared sample at ambient temperature and the preparation time can be seen in Figure 2A. The first and second peaks in the particle size diagram of hydrogel correspond to the particle size of NLC and hydrogel components, respectively.

Table 1.

Experimental results of hydrogel characterization

| Storing temperature (°C) | Characterization at preparation | Characterization after 3 months | Characterization after 6 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (nm) | PDI | EE (%) | Size (nm) | PDI | EE (%) | Size (nm) | PDI | EE (%) | |

| 4 | 107.07 ± 0.1 | 0.300 ± 0.015 | 74.00 ± 0.37 | 144.32 ± 0.2 | 0.268 ± 0.081 | 71.26 ± 0.46 | 171.73 ± 0.3 | 0.318 ± 0.076 | 68.86 ± 0.49 |

| 25 | 107.07 ± 0.1 | 0.300 ± 00.15 | 74.00 ± 0.37 | 127.37 ± 0.3 | 0.247 ± 0.022 | 69.73 ± 0.39 | 150.60 ± 0.2 | 0.300 ± 0.031 | 67.51 ± 0.41 |

| 40 | 107.07 ± 0.1 | 0.300 ± 0.015 | 74.00 ± 0.37 | 120.81 ± 0.5 | 0.368 ± 0.076 | 59.76 ± 0.61 | 143.66 ± 0.3 | 0.479 ± 0.061 | 51.47 ± 0.38 |

EE% = entrapment efficiency percentage; PDI = polydispersity index.

Figure 2.

(A) Dynamic light scattering graph of nanostructured lipid carrier–based loaded hydrogel formulation at the preparation time, (B) swelling curve, (C) viscosity curve at 0.6%wt carbomer, and (D) spreadability curve at 0.6%wt carbomer.

Rheological characterization of hydrogel.

Swelling.

The swelling curve of hydrogel samples containing 0.3%wt, 0.6%wt, and 0.9%wt of carbomer 940 as a gelling agent are shown in Figure 2B. On the basis of the results, the larger amount of gelling agent causes lower swelling percentage due to higher viscosity and greater resistance to water absorption. As shown in the figure, it seems that the best weight percentage of the gelling agent was 0.6%wt, with appropriate capacity for swelling through topical application and more consistent with the results of previous studies.34 In this formulation, after ∼5 hours, the water mass was greater than the mass of dry matter, and therefore the swelling percentage was greater than 100%. After 12 hours, the swelling percentage reached a steady level, with the maximum swelling percentage equaling 195% at a moderate rate. In general, hydrogel swelling is caused by molecular rearrangement and is related to the functional groups present along the polymer chain. Because water fills the holes in the hydrogel, the appropriate swelling percentage of the hydrogel structure results in the flow of body fluids into the hydrogel; as a result, there is sufficient and fast transition of materials from the hydrogel to the desired location, such as skin layers.12,34

Viscosity.

The results of viscosity determination for three base hydrogels, unloaded NLC, and loaded NLC formulations are shown in Table 2. Because only the viscosity of the hydrogel prepared using 0.6%wt of carbomer 940 is sufficient to facilitate transdermal delivery, this sample was selected for NLC insertion.50 This sample had the best swelling behavior. As shown in Table 2, after inserting NLCs to the hydrogel formulation, the viscosity was slightly decreased due to the addition of lipid materials.

Table 2.

Rheological characterization results of hydrogels

| Hydrogel sample | Viscosity (cP) | Spreadability factors (mm2/g) |

|---|---|---|

| Base hydrogel with 0.3%wt of carbomer | 34,780 ± 26 | 13.26 ± 0.21 |

| Base hydrogel with 0.6%wt of carbomer | 20,185 ± 12 | 8.75 ± 0.15 |

| Base hydrogel with 0.9%wt of carbomer | 9,235 ± 19 | 1.96 ± 0.27 |

| Unloaded NLC based hydrogel (0.6%wt of carbomer) | 18,530 ± 11 | 4.81 ± 0.22 |

| Loaded NLC based hydrogel (0.6%wt of carbomer) | 18,700 ± 14 | 4.56 ± 0.11 |

cP = centipoise; NLC = nanostructured lipid carrier.

In the case of rheological behavior, the viscosity of the loaded-NLC based hydrogel as the final formulation was evaluated, and the graphical representation of shear stress versus shear rate is shown in Figure 2C. Nonlinear behavior was observed that characterizes a non-Newtonian behavior. The results of fitting data with the most common models are presented in Table 3. The calculated results indicate that Ostwald–De Waele (power law) model was the most appropriate model to describe the flow behavior of hydrogel with N < 1. A value of N < 1 indicates pseudo-plastic flow as a rheological behavior between Newtonian and plastic flows.19 Consequently, a prepared hydrogel with this viscosity curve is especially useful for topical application because it can be easily applied and retained on the wound for a long time to optimize healing with appropriate flow resistance under applied shear rates.42

Table 3.

Mathematical flow models evaluated in viscosity studies

| Flow model name | Flow model equation | R 2 | Calculated equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bingham | τ = τ + ηγ | 0.7985 | τ = 386.95 + 1.29γ |

| Casson | τ = τ00.5 + η0.5 γ0.5 | 0.9527 | τ = 21.36 + 0.95 γ0.5 |

| Ostwald–De Waele | τ = k γn | 0.9938 | τ = 149 γ0.3165 |

| Herschel–Bulkley | τ = τ0 + ηγn | 0.9681 | τ = 5.69 + 178.49 γ0.3547 |

Where τ is the shear stress, τ0 is the yield stress, η is the viscosity, k is the index of consistency, n is the flow index, and γ is the shear rate.

Spreadability.

To verify the differences between the formulations, the final Sf were calculated for three base hydrogel formulations, unloaded and loaded NLC–based hydrogel (Table 2). Of the three base formulations, the one containing 0.6%wt of carbomer 940 had better spreading ability compared with the others. Because high Sf leads to excessive spreading and running on the skin and the low Sf demonstrates that a formulation needs a higher force to be spread, NLC was not added to higher and lower gelling agent percentages. After adding NLC to the hydrogel formulation, the spreading factor of hydrogels containing unloaded and loaded NLC formulations was reduced to the appropriate amount for proper distribution per application area. The spreading profiles of loaded NLC–based hydrogel containing 0.6%wt of carbomer as the final formulation is shown in Figure 2D. A controlled spreading profile with a moderate increasing rate indicates that hydrogels with appropriate spreadability have advantages, mainly when applied in injured and painful regions such as leishmaniasis wounds.32

Jointly reported analyses for NLC and hydrogel samples.

Functional group of structures.

FTIR analysis was used to examine the existence and loading of drug in the loaded NLC and loaded NLC-based hydrogel structure. As Figure 3A and B demonstrates, the FTIR spectrum of the pure Glucantime, unloaded and loaded NLC, unloaded and loaded NLC-based hydrogel, and base hydrogel formulations showed the absorption bands at 2800 to 3200 cm−1 (CH2, CH3, and –OH), 1467 to 1471 cm−1 (C–H), and 1047 to 1245 cm−1 (C–O). The peak at 1622 (C=C) is observed only in the FTIR spectrum of unloaded and loaded NLC and unloaded and loaded NLC-based hydrogel formulations. The peak at 1719 to 1739 cm−1 (C=O) is observed in the FTIR spectrum of unloaded NLC, loaded NLC, base hydrogel, and unloaded NLC-based and loaded NLC-based hydrogel formulations. The peak related to Sb–O–Sb stretching at 610 to 612 cm−1 existed only in the FTIR spectrum of loaded NLC and loaded NLC-based hydrogel, indicating Glucantime in the formulations containing the drug.51,52

Figure 3.

(A) Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) diagram of drug and nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) formulations, (B) FTIR diagram of hydrogel formulations, (C) x-ray diffraction (XRD) diagram of NLC formulations, (D) XRD diagram of hydrogel formulations, and (E) in vitro drug release from commercial ampule and loaded NLC-based hydrogel.

In the base hydrogel formulation (Figure 3B), after adding the unloaded and loaded NLC formulation, the characteristic band at 2931 cm−1 assigned to –OH stretching vibration, and the band at 1719 cm−1 attributed to C=O stretching of the carbomer 940 was shifted to 2919 cm−1 and 1728 to 1731 cm−1, respectively. This observation indicates probable chemical interaction between carbomer 940 as the gelling agent and NLC components.53

All the characteristic peaks of the unloaded NLC/unloaded NLC-based hydrogel components were present in the loaded NLC/loaded NLC based-hydrogel spectrum and no predominate shifting of existing peaks or creation of new peaks was found by adding the drug, suggesting that there were only physical interactions among the Glucantime and NLC/hydrogel excipients and no chemical interaction took place among them.54

Crystallinity.

As can be seen in Figure 3C and D, GMS lipid as a bulk material has a crystal structure with different sharp peaks, and its distinctive x-ray pattern can be partially recognized in the pattern of unloaded and loaded NLC. The presence of liquid lipid and the chemical interaction between lipids and surfactants in the nanocarrier structure disarranged the crystallinity of the solid lipid, and subsequently, the peaks of solid lipid in the two nanostructures formulation became weaker. Confirming this, the XRD pattern of physical mixture of lipids and surfactants without any chemical interaction exhibited no significant difference with that of GMS, and no destruction of the crystal structure of GMS lipid was observed. The XRD pattern of Glucantime containing antimony shows an amorphous structure without a sharp peak. The diffraction pattern of unloaded and loaded NLC/NLC-based hydrogel do not exhibit much difference in the location (2ϴ) and intensity of distinct peaks of solid lipid. This indicates that the addition of drug did not significantly change the nature of the NLCs and hydrogels,55 and most of the drug is loaded into the NLC structure. The slight reduction of peak intensity after drug loading was caused by the remaining drug having an amorphous structure in the NP environment and the fact that the total initial drug was not loaded into the NP structure according to the encapsulation efficiency results. The lower reduction of peak intensity after drug loading in the hydrogel compared with the NLC is due to the presence of drug with amorphous nature (Figure 3D). Moreover, the XRD pattern of base hydrogel indicates its amorphous structure, and because of the incorporation of NPs into the hydrogel structure, some of the peaks related to the NLC samples became slightly weaker in the XRD pattern of NLC-based hydrogels.

In vitro drug release of commercial ampule and hydrogel sample.

As Figure 3E demonstrates, the drug release percentage from the commercial ampule and the Glucantime NLC-based hydrogel formulation were 46% and 9%, respectively, after 30 minutes. This parameter after was 69% and 42% 2 hours for the commercial ampule and Glucantime NLC-based hydrogel formulations. After 6 hours, the percentage of drug released from the commercial ampule and hydrogel formulation was 83% and 69%, respectively, indicating that most of the drug was administered up to the prior 6 hours. The drug release rate of the hydrogel formulation had reached nearly 80% after 72 hours. Further, after 72 hours, the hydrogel structure’s release rate surpassed the commercial ampule release percentage but at a far slower rate. Due to having a primary quick release rate (up to 2 hours) for crossing from the skin and subsequently a sustained release rate (after 2 hours) for remaining in the wound, the two drug release profiles had a biphasic perspective that was suited for transferring drug from the skin barrier. The hydrogel formulation demonstrated better sustained drug release than a commercial ampule. In other word, the burst release of the commercial ampule of Glucantime as the primary slope was significantly controlled by drug loading in the NLC-based hydrogel formulation. Drug hydrophilicity and the tendency to cross into the aqueous medium were controlled and decreased by applying NLC lipids and viscose polymeric hydrogel. Drug release kinetics behavior from the commercial ampule and hydrogel was examined with various models. The results are shown in Table 4 and show that drug release from both commercial ampule and hydrogel structure follows the Korsmeyer–Peppas model with R2 = 0.93 and 0.98, respectively. Moreover, values of diffusion exponent (n) are < 0.5, which indicates the Fickian release of the drug from both formulations.42 The drug permeation from hydrogel probably consists of two processes: the first is drug release from the carbomer matrix, and the second is skin permeation.53

Table 4.

The results of the drug release kinetics behavior

| Release model name | Release model equation | Model parameters | Parameters for commercial ampule | Parameters for loaded NLC-based hydrogel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-order |

|

|

|

|

| First-order |

|

|

|

|

| Hixson–Crowell |

|

|

|

|

| Higuchi |

|

|

|

|

| Korsmeyer–Peppas |

|

|

|

NLC = nanostructured lipid carrier.

In vivo studies.

Antipromastigote assay.

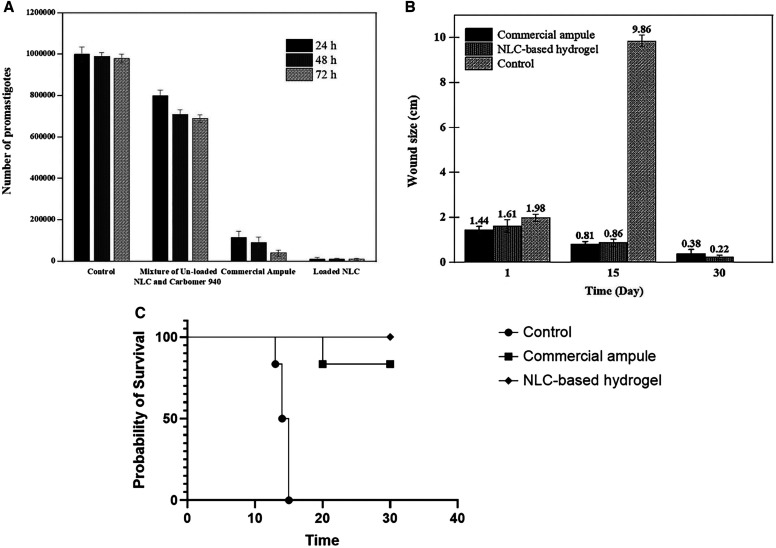

Analysis of the results of the growth of promastigotes in three time intervals for the three receiver groups, including receiver of a mixture of unloaded NLC sample and carbomer 940, loaded NLC sample, and commercial ampule are shown in Figure 4A. As can be concluded from the figure, in all the three treated groups after 24 hours, the reduction was significant compared with the primary case with 106 promastigotes (P < 0.05). In all three treated groups, there was no significant difference between the number of parasites at 24 hours and the following two time intervals, including 48 and 72 hours (P > 0.05). However, the highest suppressive effect of the three formulations was seen after 24 hours. The number of promastigotes in the control group was almost constant over 72 hours, and no significant change was observed during three time intervals (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the antipromastigote effect of all three-receiver groups at the three time intervals was significantly greater than the control group (P < 0.05). Among the three treated groups, the receiver of the loaded NLC sample group exposed the best therapeutic performance. The number of killed parasites in this group was significantly higher than in the other two groups at the three time intervals (P < 0.05). This may be because of the nanoscale structure and better placement of NLC NPs among parasites. The therapeutic effects of commercial ampule on the reduction of the promastigotes were significantly greater compared with the carbomer 940 plus unloaded NLC group at the three time intervals (P < 0.05). As the figure shows, the mixture of carbomer 940 plus the unloaded NLC sample group shows an negligible antipromastigote effect compared with the other treated groups with a significant difference (P < 0.05). This could be because of the presence of oleic acid, Tween 80, and carbomer 940 as slight anti-inflammatory compounds,26,56 which confirms that the components of hydrogel have no significant antipromastigote effects compared with Glucantime. Consequently, the newly loaded NLC-based hydrogel can be introduced as a suitable nanoscale formulation for treating leishmaniasis with a better antipromastigote effect, and its in vivo performance can be investigated.

Figure 4.

(A) Antipromastigote assay diagram, (B) lesion size variance over the time, and (C) survival curve. NLC = nanostructured lipid carrier.

Permeation from healthy mouse skin.

Permeation tests from both healthy mouse skins showed that the majority of the drug was released after 6 hours. The hydrogel sample was absorbed entirely, and no hydrogel remained on the skin. This demonstrates the ability of the hydrogel to penetrate through all skin layers. On the basis of the results, 4.1%wt and 4.5%wt of primary Glucantime were found in the blood samples of both mice after 6 hours. This low amount of drug in the bloodstream indicates most of the drug remains in the skin layers. To validate this assertion, the solutions containing crushed skin were also tested using the ICP-OES method. The results indicate a high percentage of the initial drug amount, approximately 85%, stayed in the skin layers, demonstrating an excellent capacity to cure skin wounds such as leishmaniasis. It should be noted that because of the presence of both solid and liquid lipids with inflammatory properties in the NLC structure, penetration through the skin can be enhanced.57,58 Moreover, Span 80, as a hydrophobic permeation enhancer with high polarization capability, could disrupt the skin lipid arrangement, enhance the miscibility of the skin, and increase drug partitioning into deeper skin layers to improve the skin permeation of Glucantime53 to leishmaniasis treatment in the topical administration route.

Measuring the wound size.

The average size of leishmaniasis wounds of the mice in the Glucantime commercial ampule group, Glucantime NLC-based hydrogel group, and control group are presented in Figure 4B. In the case of control group, the wound size increased significantly compared with the first day of treatment (P < 0.05) and all the mice in this group died after ∼2 weeks (Figure 4C). The results indicate that the wound area in both groups that received the drug was reduced significantly during at both 15-day intervals (P < 0.05). Therefore, the two formulations had appropriate and effective performance in leishmaniasis treatment. After 30 days, three animals in the Glucantime hydrogel group and one mouse in the commercial ampule group had complete wound healing. The wound size reduction in the NLC-based hydrogel group was significantly different from this property in the commercial ampule group (P value < 0.05). In addition to the elimination of painful injections and making it convenient for patients, transdermal hydrogel formulation showed no sign of inflammation, redness, depth, or stiffness. The hydrophilicity and early burst release of Glucantime were regulated in the transdermal hydrogel formulation, and the drug’s tendency to transfer from the wound site into the bloodstream was minimized. Furthermore, the presence of lipids and higher hydrogel viscosity increased the drug’s residence time at the lesion site and interaction with the skin surface.58

Regarding behavioral side effects, signs of dizziness, tremors, and rapid rotating movements were detected in two mice from the commercial ampule group. This was not observed in the hydrogel group.

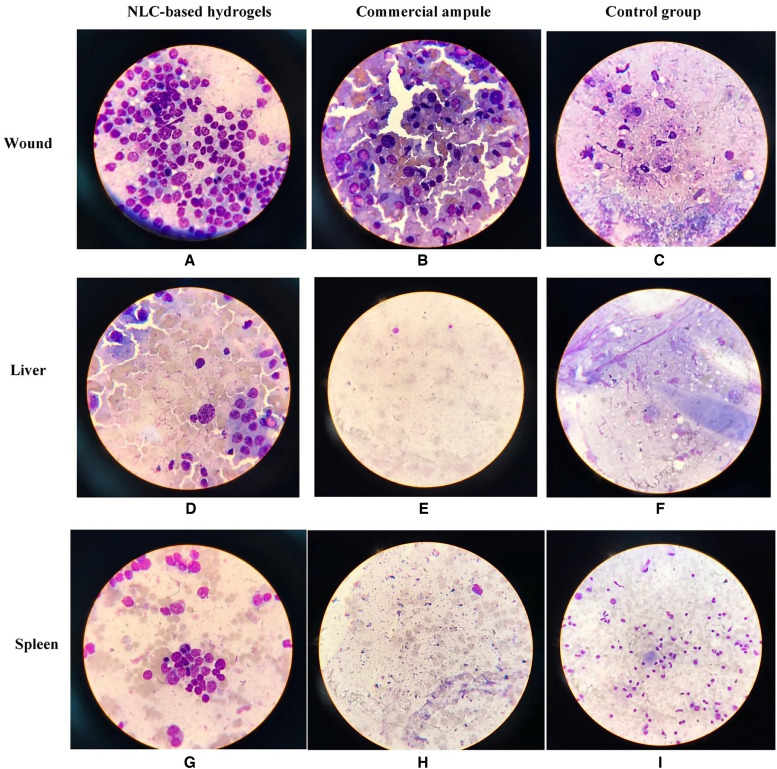

Microscopical examinations of lesions, liver, and spleen.

As Figure 5 shows, the number of parasite smears after mouse death was substantially higher in the control group than in the other groups (P < 0.05). Although the drug amount in the two treated groups was equal, the number of parasites in the skin sample of treated mice with NLC-based hydrogel was significantly lower than the parameter of treated mice with the commercial ampule (P < 0.05). This may be because there was more effective contact and interaction with the skin layers, more residence time at the lesion site, and better therapeutic effects of the NLC-based hydrogel compared with the commercial ampule. In other words, this new formulation has a significant ability to kill parasites due to its nanoscale structure and enhanced administration route.

Figure 5.

The picture of the smeared wound, liver, and spleen in all groups after death. NLC = nanostructured lipid carrier.

As shown in Figure 5, the number of parasites in liver and spleen smears after mouse death was substantially higher in the control group than in the other groups (P < 0.05). Because the number of parasites in the liver and spleen for the hydrogel group was considerably lower than that in the commercial ampule group (P < 0.05), using a hydrogel formulation resulted in improved parasite-killing power. This could be attributed to the NLC-based hydrogel group’s longer residence time at the lesion site and better therapeutic effects.

Skin allergies.

Even though inserting the injector needle into the wound renewed it and caused bleeding and injury at the time of injection and inflammation during the treatment of the commercial ampule group, there was no sign of skin allergies, including redness, inflammation, and infection discharge, in the NLC-based hydrogel group.

Hematological studies.

The average results of the hematological tests are shown in Table 5. CBC analysis findings were normal and similar in both drug recipient groups (P > 0.05), and no abnormalities in the quantity of blood cells were identified in the two treated groups. Furthermore, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and bilirubin levels in both treated groups were within normal limits, and the difference in bilirubin levels was not significant (P > 0.05). However, the AST level in the commercial ampule group was substantially more significant than in the NLC-based hydrogel group (P < 0.05). The other liver enzyme, alanine transaminase, was in the normal range in the NLC-based hydrogel group. It differed considerably from the amount in the commercial ampule group, which was significantly greater than usual (P < 0.05). As a result, replacing the commercial ampule with the innovative hydrogel formulation may eliminate the aberrant change in liver enzymes after drug delivery. The alkaline phosphatase value in the NLC-based hydrogel group was in the normal range. Its amount differed significantly from that in the commercial ampule group, which was significantly greater than normal (P < 0.05). As a result, the creation of issues for internal organs after administration of a commercial Glucantime ampule was successfully controlled by administering the NLC-based Glucantime hydrogel.

Table 5.

The results of the hematological analysis

| Test | Commercial ampule | NLC-based hydrogel | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (/µL) | 7,200 | 7,055 | 4,300–11,000 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.00 | 10.40 | 10–15 |

| Plackets (/µL) | 405,000 | 431,000 | 150,000–500,000 |

| AST enzyme (U/L) | 29 | 5 | Up to 40 |

| ALT enzyme (U/L) | 129 H | 6 | Up to 40 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 366 H | 210 | 80–306 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1–1.3 |

ALT = alanine transaminase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; NLC = nanostructured lipid carrier.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, an NLC containing Glucantime as a hydrophilic drug and an NLC-based hydrogel formulation of this drug for transdermal administration were prepared to overcome the problems of Glucantime administration, including painful injection, harmful side effects, explosive release, rapid clearance, and short circulation time in the body. Loaded NLC samples, including GMS as a solid lipid, oleic acid as liquid lipid, Span 80 as the lipophilic surfactant, and Tween 80 as the hydrophilic surfactant along with Glucantime were characterized. Subsequently, the hydrogel containing carbomer polymer as a gelling agent was generated and characterized. The drug release profile of hydrogel was more easily controlled than the commercial ampule. The permeation study confirmed the successful operation of the new formulation by obtaining low and high fractions of the initial drug in the bloodstream and dosing area of mice skin, respectively. In vivo performance of formulations was evaluated on injured BALB/C female mice. The results demonstrate that the new NLC-based hydrogel formulation had a similar anti-leishmania therapeutic effect as the commercial ampule but with lower parasite load at the wound site, liver, and spleen and also eliminated harmful side effects on blood factors, liver enzymes, and behavioral features. Controlling the hydrophilicity and initial burst release of Glucantime, reducing the tendency of the drug to pass from the wound site into the bloodstream, increasing the drug residence time in the lesion site, and better interaction with skin explain these observations. Consequently, the NLC-based hydrogel formulation proposed in this work can be a practical option for topical administration compared with the commercial Glucantime ampule with its uncomfortable injection, to treat leishmaniasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1. Torres-Guerrero E, Quintanilla-Cedillo MR, Ruiz-Esmenjaud J, Arenas R, 2017. Leishmaniasis: a review. F1000Research 6: 750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Santos DO. et al. , 2008. Leishmaniasis treatment – a challenge that remains: a review. Parasitol Res 103: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tamiru HF, Mashalla YJ, Mohammed R, Tshweneagae GT, 2019. Cutaneous leishmaniasis a neglected tropical disease: community knowledge, attitude and practices in an endemic area, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 19: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruschi F, Gradoni L, 2018. The Leishmaniases: Old Neglected Tropical Diseases, 1st edition. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jamshaid H, ud Din F, Khan GM, 2021. Nanotechnology based solutions for anti-leishmanial impediments: a detailed insight. J Nanobiotechnol 19: 1–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pourmohammadi B, Motazedian M, Handjani F, Hatam G, Habibi S, Sarkari B, 2011. Glucantime efficacy in the treatment of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 42: 502–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Varshosaz J, Arbabi B, Pestehchian N, Saberi S, Delavari M, 2018. Chitosan-titanium dioxide-Glucantime nanoassemblies effects on promastigote and amastigote of Leishmania major. Int J Biol Macromol 107: 212–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Roberts WL, McMurray WJ, Rainey PM, 1998. Characterization of the antimonial antileishmanial agent meglumine antimonate (Glucantime). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42: 1076–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mohammadzadeh M, Behnaz F, Golshan Z, 2013. Efficacy of Glucantime for treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis in central Iran. J Infect Public Health 6: 120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alishahi M, Khorram M, Asgari Q, Davani F, Goudarzi F, Emami A, Arastehfar A, Zomorodian K, 2020. Glucantime-loaded electrospun core-shell nanofibers composed of poly (ethylene oxide)/gelatin-poly (vinyl alcohol)/chitosan as dressing for cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Biol Macromol 163: 288–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Navaei A, Rasoolian M, Momeni A, Emami S, Rafienia M, 2013. Double-walled microspheres loaded with meglumine antimoniate: preparation, characterization and in vitro release study. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 40: 701–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliveira MJA, Silva EO, Braz LMA, Maia R, Amato VS, Lugão AB, Parra DF, 2014. Influence of chitosan/clay in drug delivery of Glucantime from PVP membranes. Radiat Phys Chem 94: 194–198. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marwah H, Garg T, Goyal AK, Rath G, 2016. Permeation enhancer strategies in transdermal drug delivery. Drug Deliv 23: 564–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ganesan P, Narayanasamy D, 2017. Lipid nanoparticles: different preparation techniques, characterization, hurdles, and strategies for the production of solid lipid nanoparticles and nanostructured lipid carriers for oral drug delivery. Sustain Chem Pharm 6: 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee SG, Jeong JH, Lee KM, Jeong KH, Yang H, Kim M, Jung H, Lee S, Choi YW, 2014. Nanostructured lipid carrier-loaded hyaluronic acid microneedles for controlled dermal delivery of a lipophilic molecule. Int J Nanomedicine 9: 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu H, Ramachandran C, Weiner ND, Roessler BJ, 2001. Topical transport of hydrophilic compounds using water-in-oil nanoemulsions. Int J Pharm 220: 63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Czajkowska-Kośnik A, Szekalska M, Winnicka K, 2019. Nanostructured lipid carriers: a potential use for skin drug delivery systems. Pharmacol Rep 71: 156–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ghorbanzadeh M, Golmohammadzadeh S, Karimi M, Farhadian N, 2022. Evaluation of vitamin D3 serum level of microemulsion based hydrogel containing Calcipotriol drug. Mater Today Commun 33: 104409. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doktorovova S, Souto EB, 2009. Nanostructured lipid carrier-based hydrogel formulations for drug delivery: a comprehensive review. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 6: 165–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kalat SM, Khamesipour A, Bavarsad N, Fallah M, Khashayarmanesh Z, Feizi E, Neghabi K, Abbasi A, Jaafari MR, 2014. Use of topical liposomes containing meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) for the treatment of L. major lesion in BALB/c mice. Exp Parasitol 143: 5–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Momeni A, Rasoolian M, Momeni A, Navaei A, Emami S, Shaker Z, Mohebali M, Khoshdel A, 2013. Development of liposomes loaded with anti-leishmanial drugs for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Liposome Res 23: 134–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ekambaram P, Sathali AAH, Priyanka K, 2012. Solid lipid nanoparticles: a review. Sci Rev Chem Comm 2: 80–102. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mehnert W, Mäder K, 2012. Solid lipid nanoparticles: production, characterization and applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64: 83–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zheng M, Falkeborg M, Zheng Y, Yang T, Xu X, 2013. Formulation and characterization of nanostructured lipid carriers containing a mixed lipids core. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 430: 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ebrahimi S, Farhadian N, Karimi M, Ebrahimi M, 2020. Enhanced bactericidal effect of ceftriaxone drug encapsulated in nanostructured lipid carrier against gram-negative Escherichia coli bacteria: drug formulation, optimization, and cell culture study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 9: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hayati F, Ghamsari SM, Dehghan MM, Oryan A, 2018. Effects of carbomer 940 hydrogel on burn wounds: an in vitro and in vivo study. J Dermatolog Treat 29: 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Motawea A, El Abd AE-GH, Borg T, Motawea M, Tarshoby M, 2019. The impact of topical phenytoin loaded nanostructured lipid carriers in diabetic foot ulceration. Foot 40: 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghorbanzadeh M, Farhadian N, Golmohammadzadeh S, Karimi M, Ebrahimi M, 2019. Formulation, clinical and histopathological assessment of microemulsion based hydrogel for UV protection of skin. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 179: 393–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khan AA, Mudassir J, Akhtar S, Murugaiyah V, Darwis Y, 2019. Freeze-dried lopinavir-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers for enhanced cellular uptake and bioavailability: statistical optimization, in vitro and in vivo evaluations. Pharmaceutics 11: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ortiz AC, Yañez O, Salas-Huenuleo E, Morales JO, 2021. Development of a nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) by a low-energy method, comparison of release kinetics and molecular dynamics simulation. Pharmaceutics 13: 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaba B, Fazil M, Khan S, Ali A, Baboota S, Ali J, 2015. Nanostructured lipid carrier system for topical delivery of terbinafine hydrochloride. Bull Fac Pharm Cairo Univ 53: 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Flores FC. et al. , 2015. Hydrogels containing nanocapsules and nanoemulsions of tea tree oil provide antiedematogenic effect and improved skin wound healing. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 15: 800–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bolla PK, Clark BA, Juluri A, Cheruvu HS, Renukuntla J, 2020. Evaluation of formulation parameters on permeation of ibuprofen from topical formulations using Strat-M® membrane. Pharmaceutics 12: 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. El-Sherbiny IM, Yacoub MH, 2013. Hydrogel scaffolds for tissue engineering: progress and challenges. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2013: 38–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sabale V, Kunjwani H, Sabale P, 2011. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of the topical antiageing preparation of the fruit of Benincasa hispida . J Ayurveda Integr Med 2: 124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deuschle VCKN, Deuschle RAN, Bortoluzzi MR, Athayde ML, 2015. Physical chemistry evaluation of stability, spreadability, in vitro antioxidant, and photo-protective capacities of topical formulations containing Calendula officinalis L. leaf extract. Braz J Pharm Sci 51: 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dehghani F, Farhadian N, Golmohammadzadeh S, Biriaee A, Ebrahimi M, Karimi M, 2017. Preparation, characterization and in-vivo evaluation of microemulsions containing tamoxifen citrate anti-cancer drug. Eur J Pharm Sci 96: 479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Golmohammadzadeh S, Farhadian N, Biriaee A, Dehghani F, Khameneh B, 2017. Preparation, characterization and in vitro evaluation of microemulsion of raloxifene hydrochloride. Drug Dev Ind Pharm 43: 1619–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Araújo J, Garcia ML, Mallandrich M, Souto EB, Calpena AC, 2012. Release profile and transscleral permeation of triamcinolone acetonide loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (TA-NLC): in vitro and ex vivo studies. Nanomedicine 8: 1034–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Binesh N, Farhadian N, Mohammadzadeh A, 2021. Enhanced antibacterial activity of uniform and stable chitosan nanoparticles containing metronidazole against anaerobic bacterium of Bacteroides fragilis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 202: 111691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ezatpour B, Saedi Dezaki E, Mahmoudvand H, Azadpour M, Ezzatkhah F, 2015. In vitro and in vivo antileishmanial effects of Pistacia khinjuk against Leishmania tropica and Leishmania major . Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2015: 149707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Riaz A, Ahmed N, Khan MI, Haq I-u, ur Rehman A, Khan GM, 2019. Formulation of topical NLCs to target macrophages for cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 54: 101232. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mahmoudvand H, Tavakoli R, Sharififar F, Minaie K, Ezatpour B, Jahanbakhsh S, Sharifi I, 2015. Leishmanicidal and cytotoxic activities of Nigella sativa and its active principle, thymoquinone. Pharm Biol 53: 1052–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shah PP, Desai PR, Channer D, Singh M, 2012. Enhanced skin permeation using polyarginine modified nanostructured lipid carriers. J Control Release 161: 735–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Veninga T, Wieringa R, Morse H, 1989. Pigmented spleens in C57BL mice. Lab Anim 23: 16–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Parasuraman S, Raveendran R, Kesavan R, 2010. Blood sample collection in small laboratory animals. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 1: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Averill H, Roche J, King C, 1929. Synthetic glycerides. I. Preparation and melting points of glycerides of known constitution. J Am Chem Soc 51: 866–872. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li J, Liu D, Tan G, Zhao Z, Yang X, Pan W, 2016. A comparative study on the efficiency of chitosan-N-acetylcysteine, chitosan oligosaccharides or carboxymethyl chitosan surface modified nanostructured lipid carrier for ophthalmic delivery of curcumin. Carbohydr Polym 146: 435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bhatia V, Barber R, 1955. The effect of pH variations of ointment bases on the local anesthetic activity of incorporated ethyl aminobenzoate. I. Hydrophilic ointment USP. J Am Pharm Assoc 44: 342–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sezer AD, Cevher E, Hatıpoğlu F, Oğurtan Z, Baş AL, Akbuğa J, 2008. Preparation of fucoidan-chitosan hydrogel and its application as burn healing accelerator on rabbits. Biol Pharm Bull 31: 2326–2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kaviyarasu K, Sajan D, Devarajan PA, 2013. A rapid and versatile method for solvothermal synthesis of Sb 2 O 3 nanocrystals under mild conditions. Appl Nanosci 3: 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nandiyanto ABD, Oktiani R, Ragadhita R, 2019. How to read and interpret FTIR spectroscope of organic material. Indonesian J Sci Technol 4: 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang Z. et al. , 2022. Quantitative structure–activity relationship of enhancers of licochalcone a and glabridin release and permeation enhancement from carbomer hydrogel. Pharmaceutics 14: 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pezeshki A, Ghanbarzadeh B, Mohammadi M, Fathollahi I, Hamishehkar H, 2014. Encapsulation of vitamin A palmitate in nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC)-effect of surfactant concentration on the formulation properties. Adv Pharm Bull 4 (Suppl 2): 563–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Talele P, Sahu S, Mishra AK, 2018. Physicochemical characterization of solid lipid nanoparticles comprised of glycerol monostearate and bile salts. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 172: 517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Menberu MA, Hayes AJ, Liu S, Psaltis AJ, Wormald PJ, Vreugde S, 2021. Tween 80 and its derivative oleic acid promote the growth of Corynebacterium accolens and inhibit Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 11: 810–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pereira LM, Hatanaka E, Martins EF, Oliveira F, Liberti EA, Farsky SH, Curi R, Pithon-Curi TC, 2008. Effect of oleic and linoleic acids on the inflammatory phase of wound healing in rats. Cell Biochem Funct 26: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cardoso C, Favoreto S, Jr., Oliveira LL, Vancim JO, Barban GB, Ferraz DB, Silva JS, 2011. Oleic acid modulation of the immune response in wound healing: a new approach for skin repair. Immunobiology 216: 409–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]