Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Medication nonadherence to antipsychotic drugs, which is commonly seen in patients with schizophrenia who have comorbidities, not only affects the quality of life of individuals suffering from the condition, but can also lead to worsening of disease condition, adverse outcomes, excessive use of health care resources, and higher medical costs.

OBJECTIVE:

To determine the effect of nonadherence to antipsychotics and related disease comorbidities on medical care utilization with respect to inpatient hospital visits, outpatient visits, office visits, and emergency room (ER) visits.

METHODS:

Retrospective, cross-sectional research data was obtained from the Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys (MEPS) for the years 2010-2014. The proportion of days covered (PDC) adherence measure was used to identify and classify individuals as adherent (PDC ≥ 80%) or nonadherent (PDC < 80%). A logistic regression analysis was used to further examine the effect of key study variables and comorbidity on medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia. Using the Student’s t-test, population characteristics were statistically compared between the adherent and nonadherent populations and between populations with comorbidities and without comorbidities with respect to inpatient, outpatient, office, and ER visits.

RESULTS:

Of 1.2 million people who reported having schizophrenia in MEPS from 2010 to 2014, as many as 71% were found to be nonadherent to antipsychotic medications (PDC < 80%). Results showed that women (OR = 3.594, 95% CI = 1.33-11.40, P = 0.030) and people with less than 15 years of education (OR = 20.85, 95% CI = 3.91-111.09, P = 0.0005) were more likely to be nonadherent to antipsychotic medications than all other demographics. Compared with the adherent schizophrenia population (n = 353,349), the nonadherent population (n = 868,737) had greater utilization of outpatient visits (0.68 vs. 1.92, P < 0.0001) and office visits (10.95 vs. 18.21, P < 0.0001) but had lower utilization of inpatient visits (0.82 vs. 0.45, P < 0.0001) and ER visits (1.03 vs. 0.79, P = 0.1036). Compared with the schizophrenia population without comorbidities, the population with comorbidities (a classification based on a Charlson Comorbidity Index score of ≥ 1) had greater utilization of inpatient (0.39 vs. 0.76, P < 0.0001); office (13.39 vs. 19.34, P < 0.0001); and ER visits (0.39 vs. 1.41, P < 0.0001) but had lower utilization of outpatient visits (1.86 vs. 1.21, P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Greater medical care resources are used by nonadherent populations with schizophrenia and comorbidities than those without comorbidities. Together, nonadherence and comorbidities pose significant risks to patients with schizophrenia, in clinical and financial terms, and addressing problems stemming from such risks should be an area of priority in schizophrenia management.

What is already known about this subject

Nonadherence is a major problem in the treatment of schizophrenia and causes substantial suffering by patients and their families, along with increased cost of medical care.

To a large extent, adherence to drug therapy for schizophrenia depends on the type and degree of psychiatric and related comorbidities.

Research and knowledge regarding the association of comorbidities and nonadherence with health care utilization in schizophrenia is limited and poorly documented.

What this study adds

Nonadherence rates in schizophrenia appear to be considerably more than what has been reported (about 70% or more), and associated comorbidities may be contributing to the rising rates of nonadherence.

Nonadherence to antipsychotics has the potential to cause greater use of outpatient and hospital-related resources, and comorbidities, along with some key demographics, may also further compound the problem.

Schizophrenia is a severe and chronic mental disorder that affects about 0.3%-1.6% of the population.1 Despite its low prevalence, the cost of schizophrenia accounts for 2.5% of total health care expenditures overall.2 Medication nonadherence is an increasing concern, particularly among the schizophrenia population. Medication nonadherence refers to a patient not taking prescribed medications as directed or discontinuing medication therapy altogether. Examples of nonadherence to medications include failure to fill a prescription, taking incorrect doses, missing doses, taking medication at the wrong time, and stopping medication sooner than intended.3 Nonadherence can influence treatment efficacy by preventing patients from receiving the full benefits of their prescribed medicines, leading to adverse health consequences, treatment complications, recurrent hospitalization, and eventually contributing to an undesirable disease prognosis or mortality.3,4

Direct and indirect methods are widely used to measure medication-related nonadherence in health care. Direct methods use laboratory assessments of blood, urine, and saliva samples to determine drug concentration levels. Indirect methods include patient self-reports, pill counts, refill adherence, and readings from electronic monitoring devices using microchip technologies.4

Because of the recent implementation of automated administrative systems for prescription drugs in health care organizations and pharmacies, claims data have been used widely to measure prescription drug adherence. Generally, claims-based methods measure patient adherence behavior by examining refill patterns as third-party claims are submitted for the prescribed drugs. An assumption that the rate at which patients refill prescriptions is proportional to the rate at which they consume these medications is generally made with the use of this method.5,6 Specifically, in claims-based adherence research, one of the methodologies widely employed is the use of a medication availability measure. Medication availability is generally measured by computing medication adherence ratios such as medication possession ratio (MPR) and/or proportion of days covered (PDC). Between these 2 measures, PDC is a more reliable method for measuring adherence, since it eliminates the error of double counting medications, which often occurs with MPR calculations.7

One of the widely cited studies to offer evidence of nonadherence to antipsychotic drugs is the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) trial.8 This study was initiated by the National Institute of Mental Health to compare effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs. According to the trial, roughly 74% of patients receiving antipsychotic medications were found to discontinue drug therapy during the first 18 months. Discontinuation of antipsychotic treatment was believed to be mainly because of perceived limitations in the effectiveness of the drugs taken.8 Similar findings have been documented in other studies.9-11

In addition to nonadherence concerns, comorbidities associated with schizophrenia may also complicate the treatment of schizophrenia. Patients with schizophrenia are more likely to suffer from concurrent conditions such as depression, dementia, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases.12 The presence of comorbidities are also known to negatively affect a patient’s quality of life and increase health resource utilization and costs associated with the illness.13 While there appears to be no consensus regarding the best approach for assessing the effect of comorbidities on a disease in clinical studies, various methodologies have been used in research and clinical practice to characterize the burden of multiple conditions as a single measure on a scale. One such popular index is the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), which consists of 17 different diseases weighted according to disease severity, with weights ranging from 1 to 6.14 These severity weights are based on the relative risks caused by each disease. The diseases that have a higher effect on mortality, such as cancer or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, bear the highest weight of 6, in comparison to such conditions as myocardial infarction and congestive heart failure, which are assigned lower weights (e.g., 1, 2, or 3). The final CCI score for an individual is the sum of weights assigned to all comorbidities experienced by the individual.14

Previous studies have demonstrated association between nonadherence and excessive use of hospital services and emergency psychiatric visits,15,16 with the cause likely due to relapse or persistent psychotic symptoms.17 Studies have also documented increased use of health care resources such as outpatient, inpatient and ER vists in the event of poorly managed schizophrenia.18,19 While the individual association of nonadherence and comorbidity on health outcomes has been studied separately, their combined effect on patient outcomes and medical care use has not been assessed in schizophrenia. Given this knowledge gap, the purpose of this study was to determine the effect of antipsychotic medication nonadherence and comorbidities on medical care utilization by patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Data and Sample Description

We used a retrospective database analysis approach, with data extracted from 5 years (2010-2014) of Medical Expenditure Panel Surveys (MEPS). MEPS was first conducted in 1996 and is now being carried out annually for civilian noninstitutionalized Americans by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This database consists of 3 major components from which health care data is drawn: the Household Component (MEPS-HC), the Medical Provider Component (MEPS-MP), and the Insurance Component (MEPS-IC).20

For our data analysis, files from the MEPS-HC—the Prescribed Medicines Event Files, Medical Conditions Files, and Full-Year Consolidated Data Files—were merged across multiple years. Each record in the Prescribed Medicines Event Files represents a unique prescribed medicine event, that is, a prescribed medicine reported as being purchased or otherwise obtained by a household respondent. The file contains an identifier for each unique prescribed medicine and information on the detailed characteristics associated with the event (e.g., National Drug Code number and name of the drug); Multum Lexicon—a proprietary prescription drug database of Cerner Multum—which provides drug vocabulary and prescription medicine use variables, such as the date on which the person first used the medicine, total expenditures, and sources of payments; and types of pharmacies that filled the household’s prescriptions.20

From the merged file, we selected individuals who reported a diagnosis of schizophrenia (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 295) and who had at least 1 prescription fill for an antipsychotic medication. Antipsychotic prescription refills were identified using Multum Lexicon codes built into the database: 341 for atypical antipsychotics, 210 for typical antipsychotics, and 77 for miscellaneous antipsychotics, as described in the MEPS protocol.20

Study Outcome Variables

Medication Adherence.

Medication adherence was measured using a previously developed PDC approach. PDC is widely recognized as the preferred tool for assessing medication adherence in claims data.7 PDC is calculated as the number of days of medications available divided by total number of days in a specified time interval.5,7 The MEPS database provides data on all prescription refills for a particular patient. Because this study required a calculation of PDC for each year that data was extracted, only prescription refills for a given year (independent of other years) were included in our final dataset to determine the PDC per patient per year. The following PDC formula was then used to calculate the ratio:

Total number of days supply ÷ number of days in the study period × 100

The denominator of PDC is the number of days in the study period. In order to capture long-term use of antipsychotics by schizophrenia patients, 365 days was used as the study period. The MEPS database provided the number of days supply for each patient. Every drug refill for each of the drugs for a patient in a year was aggregated to obtain the final days supply per patient. As documented in previous studies,7,21 for the cutoffs representing nonadherence scores (if the PDC was 80% or higher), the individual was considered adherent to antipsychotic therapy, and scores lower than 80% represented individuals who were potentially nonadherent to prescribed medications.7,21

Charlson Comorbidity Index.

CCI scores were used to measure disease comorbidity.22 This index identifies the presence of comorbid conditions in a patient. Each condition was assigned a weight, which depended on disease severity. These weights help assess the effect of the comorbid conditions on the primary disease state. The MEPS database does not provide disease comorbidity variables. Therefore, ICD-9-CM codes were used to identify comorbidities included in the CCI. For example, by using ICD-9-CM codes 290, 291, and 294, a variable specific for dementia was created that included all of the schizophrenia patients who were also suffering from dementia. A similar procedure was used for all of the disease comorbidity conditions included in the CCI. Next, each variable was then multiplied by the weights assigned by Charlson et al. (1987).14 So, if a schizophrenia patient had dementia (weight = 1), diabetes (weight = 2), and liver disease (weight = 3), then the CCI score for that patient was calculated to be 6 (1 + 2 + 3).

Health Care Resource Utilization.

Health care resource utilization was measured over the time period covered by the study (2010-2014) with respect to inpatient, outpatient, office, and ER visits, each of which was available as a count variable in the MEPS-HC.20

Results

Sample Description

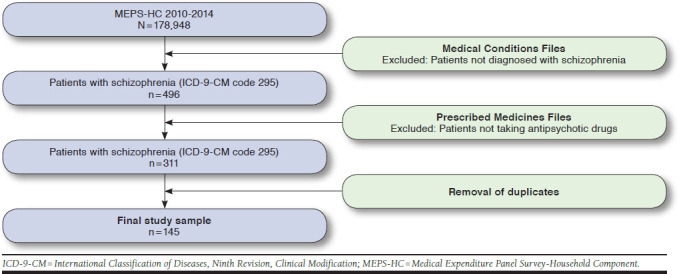

The unweighted MEPS 2010-2014 sample had 178,948 noninstitutionalized civilian adults. Among these, 496 respondents were identified as having schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM code 295). The classes of antipsychotic drugs used were atypical antipsychotics, typical antipsychotics, and miscellaneous antipsychotics. All duplicate entries were excluded. The final study sample yielded 145 patients who met the study inclusion criteria. This sample was the main schizophrenia sample (Appendix, available in online article).

The chi-square test was performed to describe the study sample according to sociodemographic characteristics. Table 1 provides detailed demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the schizophrenia population. Based on the weighted estimates, most of the schizophrenia population was found to be predominantly male (56.78%), white (67.93%), aged between 40-64 years (48.53%), single (92.19%), poor (70.82%), had lower educational attainment (87.06%), and resided mostly in the southern region of the United States (36.39%).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics of the Study Schizophrenia Population

| Characteristics | Weighted, % (N = 1,222,086) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Men | 56.78 | 0.0094 |

| Women | 43.21 | |

| Age, years | ||

| < 20 | 6.70 | < 0.0001 |

| 20-39 | 36.78 | |

| 40-64 | 48.53 | |

| ≥ 65 | 7.99 | |

| Race | ||

| White | 67.93 | < 0.0001 |

| Nonwhite | 32.06 | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 7.81 | < 0.0001 |

| Single | 92.19 | |

| Region | ||

| Northeast | 16.27 | < 0.0001 |

| Midwest | 18.23 | |

| South | 36.39 | |

| West | 29.09 | |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Poor | 70.82 | < 0.0001 |

| Near poor to low income | 19.41 | |

| Middle income to high income | 9.77 | |

| Education, years | ||

| 0-15 | 87.06 | < 0.0001 |

| > 15 | 12.94 | |

| Comorbidities (CCI score)b | ||

| 0 | 54.30 | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 1 | 45.70 | |

aSignificant at P < 0.05.

bComorbidities were estimated using the CCI. Using ICD-9-CM codes,

17 comorbidity conditions were identified to compute the CCI score.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Nonadherence Estimates: Schizophrenia Population Stratified by Adherence Status

Table 2 shows results indicating that about 71% of the individuals with schizophrenia were nonadherent to antipsychotic medications (PDC < 80%). The chi-square test was used to compare the schizophrenia sample with respect to adherence status (PDC < 80% = nonadherent vs. PDC ≥ 80% = adherent) and was further stratified by sociodemographic characteristics to understand group differences in adherence. Results indicate that a higher and statistically significant proportion of men were nonadherent to antipsychotic medications compared with women (51.84% vs. 48.15%, P = 0.01). With respect to age, more individuals aged 40-64 years (43.33%) were nonadherent to antipsychotic medications than individuals aged 20-39 years (40.60%), followed by those aged 65 years and above (8.35%) and 20 years or younger (7.72%). Overall, whites were more nonadherent to antipsychotic medications than nonwhites (63.75% vs. 36.25%, P = 0.00). With respect to marital status, a higher percentage of the nonadherent population was single compared with married persons (89.74% vs. 10.26%, P < 0.0001). A clear majority of the population with lower socioeconomic status was nonadherent to antipsychotic medications, compared with individuals with higher socioeconomic status, but the difference was not statistically significant (69.98% vs. 30.02%, P = 0.44). As for education, among the nonadherent population, 93.47% had less than 15 years of education, whereas only 6.53% had more than 15 years. In terms of regional differences, most of the nonadherent population lived in the southern region of the United States (40.24%). The 2 groups did not differ significantly from each other with respect to CCI scores.

Table 2.

Chi-Square Values for Comparison of Adherent Versus Nonadherent Populations with Schizophrenia, by Demographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Adherenta Weighted, n (%) (n = 353,349) | Nonadherentb Weighted, n (%) (n = 868,737) | Chi-Square Value | df | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Men | 243,543 (68.92) | 450,429 (51.84) | 3.54 | 1 | 0.0162 |

| Women | 109,806 (31.08) | 418,308 (48.16) | |||

| Age, years | |||||

| < 20 | 14,825 (4.19) | 67,081 (7.72) | 4.00 | 3 | < 0.0001 |

| 20-39 | 96,820 (27.40) | 3,52,713 (40.60) | |||

| 40-64 | 2,16,646 (61.31) | 3,76,410 (43.33) | |||

| ≥ 65 | 25,059 (7.09) | 72,532 (8.35) | |||

| Race | |||||

| White | 276,354 (78.21) | 553,857 (63.75) | 2.85 | 1 | 0.0071 |

| Nonwhite | 769,95 (21.79) | 314,880 (36.25) | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 6,369 (1.80) | 89,099 (10.26) | 2.95 | 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Single | 346,980 (98.20) | 779,638 (89.74) | |||

| Region | |||||

| Northeast | 58,621 (16.59) | 140,281 (16.14) | 3.163 | 3 | 0.0034 |

| Midwest | 89,427 (25.30) | 133,400 (15.35) | |||

| South | 95,142 (26.92) | 249,643 (40.24) | |||

| West | 110,159 (31.17) | 245,413 (28.24) | |||

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| Poor | 257,636 (72.91) | 607,909 (69.98) | 0.838 | 2 | 0.4430 |

| Near poor to low income | 73,578 (20.82) | 163,584 (18.83) | |||

| Middle income to high income | 22,134 (6.27) | 97,244 (11.19) | |||

| Education, years | |||||

| 0-15 | 251,987 (71.31) | 811,999 (93.47) | 12.98 | 1 | < 0.0001 |

| > 15 | 101,362 (28.69) | 56,738 (6.53) | |||

| Comorbidities (CCI score)d | |||||

| 0 | 189,938 (53.75) | 473,730 (54.53) | 0.0073 | 1 | 0.9038 |

| ≥ 1 | 163,411 (46.25) | 395,007 (45.47) | |||

aAdherent = PDC ≥ 80%.

bNonadherent = PDC < 80%.

cSignificant at P < 0.05. Statistically significant at α = 0.05.

dComorbidities were estimated using the CCI. Using ICD-9-CM codes, 17 comorbidity conditions were identified to compute the CCI score.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; df = degrees of freedom; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; PDC = proportion of days covered.

Predictors of Medication Nonadherence

A logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the effect of demographic and socioeconomic variables and CCI scores on medication adherence (Table 3). The logit model consisted of age, gender, race, marital status, region, socioeconomic status, and CCI score as predictor variables. Medication adherence was dichotomized (adherent and nonadherent) as the dependent variable. We performed a multicollinearity assessment using the variance inflation factor, tolerance value, and goodness-of-fit test to estimate and rule out any interactive effects of independent variables on nonadherence. While there is no strict cutoff, tolerance values less than 0.4 are considered to be indicative of the presence of multicollinearity, whereas a variance inflation factor closer to or greater than 10 is considered as representative of multicollinearity.23 Collinearity was not found between any of the independent variables assessed for inclusion in the model.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression to Determine Effect of Predictors on Medication Nonadherence in Schizophrenia Population, Weighted Samplea

| Category | Reference | Estimate | Standard Error | OR | 95% CI | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Women | Men | 0.2583 | 2.020 | 3.594 | 1.333-11.405 | 0.0300 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| < 20 | 20-39 years | -0.3358 | 1.5707 | 0.715 | 0.0031-16.420 | 0.8314 |

| 40-64 | 0.4748 | 0.7621 | 1.608 | 0.351-7.356 | 0.5354 | |

| ≥ 65 | 0.6000 | 1.0339 | 1.822 | 0.232-14.341 | 0.5636 | |

| Race | ||||||

| Nonwhite | White | 0.5804 | 0.5858 | 1.787 | 0.561-5.687 | 0.3234 |

| Region | ||||||

| Midwest | Northeast | -0.1071 | 0.9760 | 0.898 | 0.131-6.185 | 0.9128 |

| South | 0.2169 | 0.7961 | 1.242 | 0.258-5.993 | 0.7856 | |

| West | -0.0399 | 0.8609 | 0.961 | 0.175-5.268 | 0.9631 | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | Single | -2.7308 | 1.4347 | 0.065 | 0.004-1.111 | 0.0490 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Near poor to low income | Poor | -0.0801 | 0.7315 | 0.923 | 0.787-89.262 | 0.9130 |

| Middle income to high income | 2.1262 | 1.1967 | 8.383 | 0.156-1.506 | 0.0777 | |

| Education | ||||||

| 0-15 years | > 15 years | 3.0374 | 0.8464 | 20.852 | 3.914-111.098 | 0.0005 |

| Comorbidity (CCI score)c | ||||||

| ≥ 1 | 0 | -0.7246 | 0.5737 | 0.484 | 0.156-1.506 | 0.2086 |

aPredictors were sociodemographics and CCI score.

bSignificant at P < 0.05.

cComorbidies were estimated using the CCI. Using ICD-9-CM codes, 17 comorbidity conditions were identified to compute the CCI score.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI = confidence interval; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; OR = odds ratio.

While controlling for other factors, it was observed that women had higher odds of being nonadherent to antipsychotic medication compared with men, and this association was found to be statistically significant (odds ratio [OR] = 3.594, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 1.333-11.405, P = 0.03). Married individuals had lower odds of nonadherence to antipsychotic medications compared with unmarried persons (OR = 0.065, 95% CI = 0.004-1.111, P = 0.04) when controlled for all other variables. Similarly, controlling for other variables, individuals with less than 15 years of education were more likely to be nonadherent to antipsychotic medications compared with patients who had more than 15 years of education (OR = 20.852, 95% CI = 3.914-111.098, P = 0.00). All of these results were statistically significant, further underscoring the role of gender, marital status, and education as useful predictors of medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia.

Health Resource Use in Adherent Versus Nonadherent Groups

We examined and compared resource utilization profiles for the 2 groups with respect to 4 types of resource use: hospitalization, outpatient, office, and ER visits. As shown in Table 4, the Student’s t-test highlights the mean differences in health service utilization with respect to these variables between the 2 groups. Compared with the adherent sample, the nonadherent sample had a significantly lower number of inpatient visits (0.82 vs. 0.45, P < 0.0001) but had a greater number of outpatient (0.68 vs. 1.92, P < 0.0001) and office visits (10.95 vs. 18.21, P < 0.0001), respectively. Moreover, the nonadherent sample also had fewer ER visits (1.03 vs. 0.79), but the difference was not statistically significant. Overall, barring inpatient and ER visits, the other 2 health care resource categories had significantly higher use among the nonadherent schizophrenia group than the adherent group.

Table 4.

Student’s T-test for Differences in Health Care Utilization Between Adherent and Nonadherent Population, Weighted Sample

| Health Care Utilization | Nonadherent Populationa | Adherent Populationb | T-value | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number of visits per person | Mean number of visits per person | |||

| Inpatient visits | 0.45 | 0.82 | -2.03 | < 0.0001 |

| Outpatient visits | 1.92 | 0.68 | 1.24 | < 0.0001 |

| Office visits | 18.21 | 10.95 | 1.78 | < 0.0001 |

| ER visits | 0.79 | 1.03 | -0.99 | 0.1000 |

aNonadherent = PDC ≥ 80%.

bAdherent = PDC < 80%.

cSignificant at P < 0.05.

ER = emergency room; PDC = proportion of days covered.

Comparison of Health Resource Use Among Individuals with Schizophrenia with and Without Comorbidities

For individuals with schizophrenia with and without comorbidities, statistical differences between the 2 groups with respect to the same 4 categories of resource use were studied using a similar analysis. For this purpose, 2 subsets of the schizophrenia population (comorbidities vs. no comorbidities) were created by using CCI cutoff scores (CCI score = 0 and CCI score ≥ 1). Table 5 illustrates the mean difference in health care utilization between these 2 groups. Compared with the no comorbidities group (CCI = 0), the comorbidity sample (CCI ≥ 1) had a substantially higher number of inpatient visits (0.39 vs. 0.76, P < 0.0001); office visits (13.39 vs. 19.34, P < 0.0001); and ER visits (0.39 vs. 1.41, P < 0.0001). With respect to outpatient visits, however, we observed that the number for such visits for the group without comorbidities exceeded that of the group with comorbidities (1.86 vs. 1.21, P < 0.0001). All differences were statistically significant. Overall, the comorbid schizophrenia population had greater utilization of inpatient, office, and ER visits but not outpatient visits.

Table 5.

Student’s T-test for Differences in Health Care Utilization Between Populations with CCI = 0 and CCI ≥ 1, Weighted Sample

| Health Care Utilization | CCI = 0a | CCI≥ 1b | T-value | P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean number of visits per person | Mean number of visits per person | |||

| Inpatient visits | 0.39 | 0.76 | -2.36 | < 0.0001 |

| Outpatient visits | 1.86 | 1.21 | 0.71 | < 0.0001 |

| Office visits | 13.39 | 19.34 | -1.60 | < 0.0001 |

| ER visits | 0.39 | 1.41 | -5.00 | < 0.0001 |

aIndividuals without comorbidities.

bIndividuals with comorbidities.

cSignificant at P < 0.05.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; ER = emergency room.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to assess the association of nonadherence and disease comorbidity with health resource utilization in patients with schizophrenia. Study results demonstrated that nonadherence and the presence of comorbidities lead to an increase in the use of health resources in terms of inpatient, outpatient, office, and ER visits. To our knowledge, this study is the first to address this research objective. Based on PDC estimates, this study found that more than 70% of the schizophrenia population was nonadherent to antipsychotic medications, a finding that agreed with previous studies.24,25

While not discounting the likely effects of therapeutic class and medication-related factors affecting adherence (which were not assessed here), this study demonstrates that demographic variables such as race, age, sex, marital status, region, and socioeconomic status may be as important as pharmacological aspects for predicting nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia. It was evident from our results that among the schizophrenia population nonadherence was positively and significantly associated with gender (female), marital status (unmarried), and education (lower education; Table 3). Women were 3.6 times more likely to be nonadherent than men (OR = 3.594, 95% CI = 1.333-11.405), which was also in agreement with previous research.26 It is worth noting, however, that some studies have found no such association between nonadherence to antipsychotic medications and gender.27,28 Therefore, the evidence of association between gender and nonadherence remains contradictory and mostly inconclusive. With regard to association between marital status and nonadherence, married persons were 93.5% less likely to be nonadherent than unmarried individuals. Similar results were also reported by another study.26 This effect may be largely attributed to the benefit of having family support, which could be crucial for medication adherence, since such individuals are likely to be more attentive to their health care needs and compliant with professional instructions.

Furthermore, education was also found to be positively correlated with nonadherence in our study. As hypothesized in the study, individuals with less than 15 years of education showed greater odds of nonadherence (20 times more likely) to antipsychotic medications compared with those with more than 15 years of education (OR = 20.852, 95% CI = 3.914-111.098). This result is also consistent with past findings.29 It can be argued that lower levels of education may contribute to poorer understanding and comprehension of professional advice, as well as lack of perceived importance of antipsychotic medications, possibly affecting continuity of treatment and medication adherence. Clearly, education can be an important contributor to treatment adherence in schizophrenia. Nonadherence and its association with sociodemographic variables underscores the importance of identifying priority groups for interventions designed to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia management.

In addition, we examined the effect of nonadherence across 4 utilization categories and found that nonadherent individuals tended to use office-based resources and more than hospital-based inpatient care. Lower than expected hospital visits overall were perhaps due to a possible lack of health insurance coverage, which might have prompted increased visits to more accessible ER care and other safety net options. Any hospital-based care, particularly in the adherent group may have been due to clinical complications and disease morbidity and not necessarily due to nonadherence problems. However, these findings are generally not in agreement with previous studies,15,30 which also report contradictory findings regarding the relationship between adherence and inpatient care. With respect to increased primary care and outpatient visits, worsening health condition attributable to nonadherence, along with any complications and adverse events associated with drug therapy, might have led to more primary care consultations and outpatient care. Future investigators must explore this possibility. Moreover, greater use in this case may also be attributed to routine medical exams related to primary and preventive care unrelated to schizophrenia, a possibility that was not explored in our study.

We also examined the effect of comorbidities across the 4 utilization categories. Results demonstrate that schizophrenia comorbidities led to use of more health care resources than considered normal (Table 5). Specifically, with respect to inpatient, office, and ER visits, presence of comorbidities may have accounted for more of such visits than those who did not have comorbidities. These results are also consistent with findings reported in a previous study.18 As should be expected, the greater the degree and number of comorbidities, the greater is treatment complexity and nonadherence and the greater the potential for rising medical care use.

Limitations

There are 2 limitations to this study. First, inherent in the use of adherence measurement tools in database research is the lack of accuracy of these tools; one cannot be reasonably certain whether the medication was ingested by the patient because MEPS data relies only on self-reports of refill actions. PDC calculations assume that the doses of medications in hand (days supply) as reported in the surveys are the actual doses taken by the patient. This may often lead to a situation where actual adherence maybe overestimated. Furthermore, if patients filled their antipsychotic medication scripts from sources other than that linked to their insurance, the PDC estimates may lead to erroneous interpretations, since such transactions will likely not be captured by MEPS data.

Second, the version of the CCI included in our study covered only 17 disease conditions. Therefore, a patient reporting a condition not listed as a comorbidity in the CCI would not be represented, and the burden imposed by that disease would not be known. Besides, as previously noted, the CCI inventory does not cover any mental health conditions other than dementia, further limiting the ability to model mental health comorbidities in a study of this kind.

Conclusions

Prevalence of nonadherence in schizophrenia is high (> 70%) and remains a significant problem. Greater medical care resources are also used by those who are nonadherent to medications with diagnosed comorbidities than those without such comorbidities. While nonadherence is particularly associated with greater use of outpatient and office visits, comorbidity consumes greater hospital resources related to inpatient and emergency care. Presence of comorbidities clearly compounds the problem of nonadherence. Together, nonadherence and comorbidities pose significant risks, in clinical and economic terms, for schizophrenia management and should be an area of priority with regard to screening, assessment, and treatment interventions of patients with schizophrenia.

APPENDIX A.

Flowchart Detailing Data Extraction and Sample Selection

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, et al. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(8):668-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitch K, Iwasaki K, Villa KF. Resource utilization and cost in a commercially insured population with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(1):18-26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chia LR, Schlenk EA, Dunbar-Jacob J. Effect of personal and cultural beliefs on medication adherence in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2006;23(3):191-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, Hudson TJ, West DS, Martin BC. Prospective validation of eight different adherence measures for use with administrative claims data among patients with schizophrenia. Value Health. 2009;12(6):989-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grymonpre RE, Didur CD, Montgomery PR, Sitar DS. Pill count, self-report, and pharmacy claims data to measure medication adherence in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32(7-8):749-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pharmacy Quality Alliance . PQA adherence measures. Available at: https://www.pqaalliance.org/adherence-measures. Accessed November 16, 2018.

- 8.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of anti-psychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients take their medicine? Reasons and solutions in psychiatry. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13:336-46. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCombs JS, Nichol MB, Stimmel GL, Shi J, Smith RR. Use patterns for antipsychotic medications in Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 19):5-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Eijken M, Tsang S, Wensing M, de Smet PA, Grol RP. Interventions to improve medication compliance in older patients living in the community: a systematic review of the literature. Drugs Aging. 2003;20(3):229-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: a population-based controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(11):1133-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, Ruwaard D, Satariano WA, van den Bos GA. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):661-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A. new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, Furiak NM, Montgomery W. Medication adherence levels and differential use of mental-health services in the treatment of schizophrenia. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knapp M, King D, Pugner K, Lapuerta P. Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication regimens: Associations with resource use and costs. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:509-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morken G, Widen JH, Grawe RW. Non-adherence to antipsychotic medication, relapse and rehospitalisation in recent-onset schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lafeuille MH, Dean J, Fastenau J, et al. Burden of schizophrenia on selected comorbidity costs. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(2):259-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, McEvoy JP, et al. The impact of obesity on health care costs among persons with schizophrenia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(1):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality . Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Household Component summary tables. Available at: https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepstrends/home/index.html. Accessed November 6, 2018.

- 21.Martin BC, Wiley-Exley EK, Richards S, Domino ME, Carey TS, Sleath BL. Contrasting measures of adherence with simple drug use, medication switching, and therapeutic duplication. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(1):36-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Formiga F, Moreno-Gonzalez R, Chivite D, Franco J, Montero A, Corbella X. High comorbidity, measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index, associates with higher 1-year mortality risks in elderly patients experiencing a first acute heart failure hospitalization. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(8):927-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dormann CF, Elith J, Bacher S, et al. Collinearity: a review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography. 2013;36(1):27-46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al. Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Med Care. 2002;40(8):630-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sultan M, Hashem R, Mohson N, et al. Studying medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia: focus on antipsychotic-related factors. Middle East Current Psychiatry. 2016;23(1):27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eticha T, Teklu A, Ali D, Solomon G, Alemayehu A. Factors associated with medication adherence among patients with schizophrenia in Mekelle, Northern Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0120560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acosta FJ, Bosch E, Sarmiento G, Juanes N, Caballero-Hidalgo A, Mayans T. Evaluation of noncompliance in schizophrenia patients using electronic monitoring (MEMS) and its relationship to sociodemographic, clinical and psychopathological variables. Schizoph Res. 2009;107(2-3):213-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linden M, Godemann F, Gaebel W, et al. A prospective study of factors influencing adherence to a continuous neuroleptic treatment program in schizophrenia patients during 2 years. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(4):585-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vassileva I, Milanova V, Asan T. Predictors of medication non-adherence in Bulgarian outpatients with schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J. 2014;50(7):854-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joe S, Lee JS. Association between non-compliance with psychiatric treatment and non-psychiatric service utilization and costs in patients with schizophrenia and related disorders. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]