Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Regulatory approval of novel therapies by the FDA does not guarantee insurance coverage requisite for most clinical use. In the United States, the largest health insurance payer is the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which provides Part D prescription drug benefits to over 43 million Americans. While the FDA and CMS have implemented policies to improve the availability of novel therapies to patients, the time required to secure Medicare prescription drug benefit coverage—and accompanying restrictions—has not been previously described.

OBJECTIVE:

To characterize Medicare prescription drug plan coverage of novel therapeutic agents approved by the FDA between 2006 and 2012.

METHODS:

This is a cross-sectional study of drug coverage using Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit plan data from 2007 to 2015. Drug coverage was defined as inclusion of a drug on a plan formulary, evaluated at 1 and 3 years after FDA approval. For covered drugs, coverage was categorized as unrestrictive or restrictive, which was defined as requiring step therapy or prior authorization. Median coverage was estimated at 1 and 3 years after FDA approval, overall, and compared with a number of drug characteristics, including year of approval, CMS-protected class status, biologics versus small molecules, therapeutic area, orphan drug status, FDA priority review, and FDA-accelerated approval.

RESULTS:

Among 144 novel therapeutic agents approved by the FDA between 2006 and 2012, 14% (20 of 144) were biologics; 40% (57 of 144) were included in a CMS-protected class; 31% (45 of 144) were approved under an orphan drug designation; 42% (60 of 144) received priority review; and 11% (16 of 144) received accelerated approval. The proportion of novel therapeutics covered by at least 1 Medicare prescription drug plan was 90% (129 of 144) and 97% (140 of 144) at 1 year and 3 years after approval, respectively. At 3 years after approval, 28% (40 of 144) of novel therapeutics were covered by all plans. Novel therapeutic agents were covered by a median of 61% (interquartile range [IQR] = 39%-90%) of plans at 1 year and 79% (IQR = 57%-100%) at 3 years (P < 0.001). When novel therapeutics were covered, many plans restricted coverage through prior authorization or step therapy requirements. The median proportion of unrestrictive coverage was 29% (IQR = 13%-54%) at 3 years. Several drug characteristics, including therapeutic area, FDA priority review, FDA-accelerated approval, and CMS-protected drug class, were associated with higher rates of coverage, whereas year of approval, drug type, and orphan drug status were not.

CONCLUSIONS:

Most Medicare prescription drug plans covered the majority of novel therapeutics in the year following FDA approval, although access was often restricted through prior authorization or step therapy and was dependent on plan choice.

What is already known about this subject

Regulatory approval of novel therapies by the FDA does not guarantee insurance coverage requisite for most clinical use.

There has been no systematic examination of the timing of or restrictions on insurer coverage of novel therapeutic agents following their approval by the FDA.

Medicare prescription drug benefit plans, which cover more than 40 million Americans, can provide insight into coverage trends.

What this study adds

While 90% of novel therapeutic agents were covered by at least 1 plan in the year after FDA approval, coverage patterns were heterogeneous and often used prior authorization or step therapy restrictions.

The median proportion of plans providing unrestrictive coverage was 29% at 3 years, and few therapeutics (4%) were covered by all plans without restrictions at 3 years.

CMS-protected drug status, FDA priority review, FDA-accelerated approval, and therapeutic area were each associated with higher rates of coverage, whereas year of approval, drug type, and orphan drug status were not.

Every year dozens of novel therapeutic agents—small molecule drugs and biologics—enter the health care marketplace following regulatory agency approval.1 Regulatory approval, however, ensures neither payer reimbursement nor patient access. Regulatory agencies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), are tasked with determining whether medical products are safe and effective for public use. Insurers, however, must decide which medical products and services are “reasonable and necessary,” which is the standard used in determining coverage.2,3 As a result, in the United States, patient access to new medications following FDA approval is effectively determined by a complex system of public and private payers.

In the United States, the largest payer is a government agency, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which provides coverage for older adults through the Medicare program and for socially vulnerable children and families through the Medicaid program. Medicare is the larger of the 2 programs, with services covering roughly 1 in 6 (56.8 million) Americans and providing prescription drug benefits to 43.2 million in 2016.4 Medical services and physician-administered drugs are generally covered under Parts A and B, while prescription drug benefits are generally covered under Part D plans. Medicare Advantage, or Part C plans, cover all of these same services under health maintenance organization arrangements. CMS occupies a unique role in the American health care system because its coverage decisions may alter clinical practice, influence national coverage trends, and inform public debate.5

By law, however, Medicare is prohibited from negotiating directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers.6 Medicare prescription drug plan benefits are contracted to and sold by private insurers, who control coverage and benefits and negotiate pharmaceutical rebates, theoretically reducing the cost to consumers. This arrangement means that CMS does not always directly determine patient access to individual prescription medications. The FDA and CMS have implemented policies to support more rapid and reliable availability of novel therapeutics to patients. The FDA, for example, offers orphan drug designations, priority review, and accelerated approval,7,8 while CMS mandates review timelines and has designated 6 protected drug classes in which plans must cover “all or substantially all medications.”9 The evolving role of these programs in facilitating patient access to novel therapeutics has been the subject of continuing analysis and proposed change.10-13

Related to these policies, previous research has shown that there may be significant delays between FDA approval of new technologies and CMS coverage, which then delays clinical adoption.14-16 In response, efforts have been made to align the FDA and CMS review schedules by developing a parallel review process for medical technologies seeking coverage under Medicare Parts A and B—which was made permanent in 201617,18—to ensure that CMS issues a national coverage determination shortly after FDA approval.19 However, no such program currently exists for prescription drug coverage.

To date, there has been no study to determine if there are CMS coverage delays for newly FDA-approved prescription drugs. To quantify the timing of CMS coverage, we used Medicare prescription drug benefit formulary data from 2007 through 2015 to characterize rates of plan formulary coverage of therapeutic agents approved by the FDA between 2006 and 2012. In this study, we have analyzed the time between FDA approval and CMS coverage, differentiating between restrictive and unrestrictive coverage, as well as stratifying analyses based on therapeutic characteristics, such as CMS-protected drug class status, and regulatory characteristics, such as FDA priority review and accelerated approval status. These results provide unique insights into how federal policies influence coverage of novel therapeutic agents.

Methods

FDA Drug Approvals

We identified all novel therapeutic agents approved by New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) between 2006 and 2012. Following a previous approach,20 we excluded reformulations of drugs, combination therapies, nontherapeutic agents (e.g., imaging contrast), and subsequent approvals of rebranded drugs for new indications. We also excluded drugs used exclusively for those indications outside the purview of Part D coverage (e.g., pediatric indication, over the counter, and weight loss) and those withdrawn from market less than 3 years after approval. Drug names were linked to their National Drug Code (NDC) numbers, and unmatched compounds were excluded. All drugs for which no coverage by any formulary was observed over the study period were reviewed to ensure that it was reasonable to expect Part D prescription drug coverage. Physician-administered drugs typically covered by Medicare Part A or Part B were excluded,9 including drugs approved for in-hospital use only (alvimopan, used to improve postoperative bowel healing, and clevidipine for intravenous blood pressure control); intravitreal injections (ranibizumab, aflibercept, and ocriplasmin); procedural agents (fospropofol, collagenase, and polidocanol); and infusions administered in the outpatient setting, such as chemotherapy agents (brentuximab and carfilzomib).

We determined the following characteristics for all novel therapeutics at the time of original approval by reviewing the relevant documentation in the Drugs@FDA database1: drug type (small molecule drug or biologic), orphan drug designation, FDA priority review designation, and FDA-accelerated approval status. In addition, we determined broad therapeutic area according to World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes, as used in a previously published work.20 Categories were autoimmune, cancer, cardiovascular/diabetes/lipids, dermatologic, infectious disease, neurologic, psychiatric, and other. Finally, we determined whether the drugs reasonably fell into a CMS-protected drug class, which are immunosup-pressants for transplant organ rejection prophylaxis, antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, antiretrovirals for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and antineoplastics.9

CMS Formulary Coverage

We determined Medicare prescription drug benefit formulary coverage using the CMS Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files.21 These files include data on formularies, including Medicare Part D standalone prescription drug plans and Medicare Advantage (Part C prescription drug plans). We obtained data from 2007 to 2015 (Quarter 2), and we linked each formulary to its plan (~3,000 plans). We excluded plans lacking formulary data and special needs plans (~600 plans annually) because they do not reflect general drug availability.

Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome was drug coverage, defined as inclusion of a drug on a plan formulary. No coverage was defined as a plan formulary on which the drug name did not appear, normally requiring a patient to assume full responsibility for the drug costs, except in rare circumstances (such as appeal or grand-fathered previous coverage). As a secondary outcome, we categorized coverage as restrictive or unrestrictive, defining restrictive coverage as plans requiring step therapy or prior authorization. At the plan level, we determined the percentage of plans covering each included drug in each year following approval, stratified by unrestrictive and restrictive coverage. Drug coverage was estimated at year 1 and year 3 following FDA approval.

Data Analysis

For each novel therapeutic agent, we used descriptive statistics to determine the percentage of plans providing coverage at years 1 and 3 following FDA approval. We then determined the percentage of plans achieving coverage at these predefined thresholds: any plan coverage, 50% of plans providing coverage, 90% of plans providing coverage, and 100% of plans providing coverage. The median coverage percentage was determined at each time point. Nonparametric paired tests (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) were used to compare median plan coverage 1 year and 3 years after FDA approval. At a plan level, we compared median coverage at 1 and 3 years after FDA approval by subgroups using either Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate: year of approval, approval pathway (NDA vs. BLA), protected drug class, orphan drug designation, priority review status, accelerated approval, and therapeutic area. P values are reported without correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). Institutional review board approval was not required for any portion of this study, since it did not include human subject research.

Results

Novel Therapeutic Sample and Medicare Prescription Drug Plans

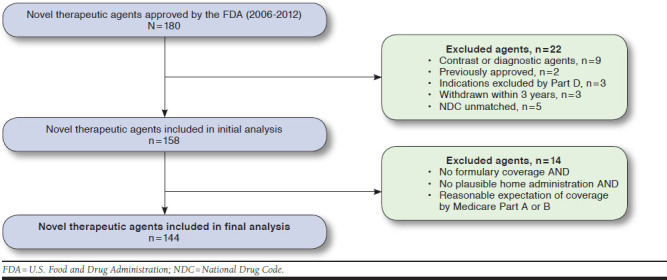

There were 180 new small molecule drugs and biologics approved between 2006 and 2012 (Figure 1). We initially excluded 22 drugs based on the following reasons: (a) 9 contrast or in-hospital diagnostic agents, (b) 2 agents were previously approved for alternate indications, (c) 3 agents were approved for an indication outside the purview of Part D coverage, (d) 3 agents were withdrawn from market less than 3 years following approval, and (e) 5 agents were excluded due to inability to confirm an NDC match (see Appendix A, available in online article). Thus, our initial analysis consisted of 158 newly FDA-approved therapeutics. Subsequently, an additional 14 novel therapeutic agents (see Appendix B, available in online article) were excluded from the study because they had no expectation of Part D prescription drug coverage, based on (a) no formulary coverage, (b) no plausible home administration, and (c) reasonable expectation of coverage by Medicare Part A or B. The final analysis therefore consisted of 144 novel therapeutic agents.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of FDA-Approved Novel Therapeutic Agents in Study Sample, 2006-2012

The number of FDA approvals included in the final sample varied by year, ranging from a low of 14 in 2007 to a high of 27 in 2012. Fourteen percent (20 of 144) were biologics; 40% (57 of 144) fell into a CMS-protected class; 31% (45 of 144) were approved under an orphan drug designation; 42% (60 of 144) received priority review; and 11% (16 of 144) received accelerated approval.

Excluding special needs plans and plans without corresponding formulary data, there was a range of Medicare prescription drug plans from a high of 3,095 in 2008 to a low of 2,538 in 2011.

Novel Therapeutic Coverage

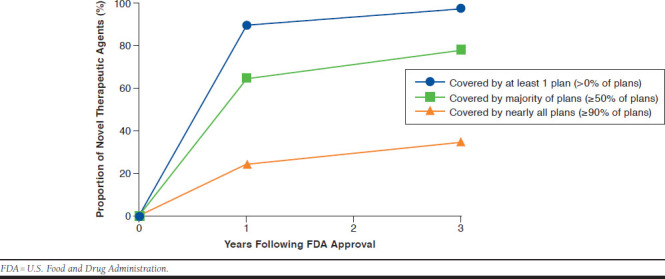

Coverage of novel therapeutic agents tended to increase over time (Figure 2). The proportion of novel therapeutics covered by at least 1 Medicare plan increased from 90% (129 of 144) to 97% (140 of 144) at 1 and 3 years following approval, respectively. The proportion of novel therapeutics covered by the majority (≥ 50%) of plans increased from 65% (93 of 144) to 78% (112 of 144) at 1 year and 3 years following approval, respectively. The proportion of novel therapeutics covered by greater than 90% of plans increased from 25% (36 of 144) to 35% (51 of 144) of therapies at 1 year and 3 years following approval, respectively. The proportion of novel therapeutics covered by all plans increased from 15% (22 of 144) to 28% (40 of 144) at 1 and 3 years following approval, respectively. Of those with coverage by all plans at 3 years following approval, 90% (36 of 40) were in a CMS-protected drug class, and 15% (6 of 40) had no coverage restrictions. Therapeutics with universal coverage without restriction were limited to antiretroviral HIV medications—darunavir, maraviroc, raltegravir, etravirine, rilpivarine, and the combination pill elvite-gravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir.

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of Novel Therapeutic Agents Covered by Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Plans Stratified by Threshold Coverage Level

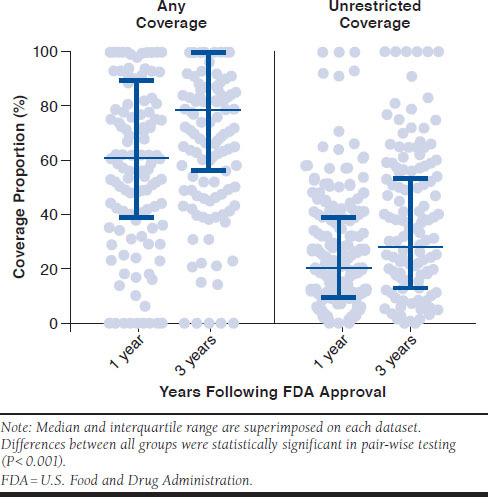

Among all newly approved therapeutics, the median proportion of plans with any coverage at year 1 was 61% (interquartile range [IQR] = 9%-90%) and 79% (IQR = 57%-100%) at year 3 (Figure 3). The median proportion of plans with unrestrictive coverage was 21% (IQR = 9%-39%) at year 1 and 29% (IQR = 13%-54%) at year 3. There was a statistically significant difference between all pair-wise comparisons of total and unrestrictive coverage at year 1 and year 3 (P < 0.001).

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of Eligible Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Plans Covering Novel Therapeutic Agents by Time Since FDA Approval

Four drugs (3%) had no coverage 3 years following approval. Two of the drugs, abobotulinumtoxina (injection muscle relaxant) and dienogest estradiol valerate (Natazia, an oral contraceptive therapy) received coverage after 4 years. One drug, glucarpidase (used to treat methotrexate toxicity), was initially covered but lost coverage, while spinosad (used as an antilice treatment) had no coverage at any time.

Characteristics Associated with Novel Therapeutic Coverage

There were significant differences in coverage observed when comparing novel therapeutic characteristics (Table 1). Differences in coverage rates were associated with protected class status, priority review status, accelerated approval, and therapeutic area but not with orphan drug status or biologics versus small molecules. For instance, among therapeutics included within a CMS-protected class, the median proportion of plans providing any coverage at 1 year following approval was 93% (IQR = 62%-100%), compared with 50% (IQR = 29%-62%) among those not within a protected class (P < 0.001). Similarly, among drugs approved with priority review, the median proportion of plans providing any coverage at 1 year following approval was 75% (IQR = 58%-93%), compared with 51% (IQR = 29%-75%) among those approved through the standard pathway (P < 0.001). Among therapeutics that received accelerated approval, the median proportion of plans providing any coverage in the year following approval was 91% (IQR = 62%-94%), compared with 58% (IQR = 37%-79%) among those without accelerated approval (P = 0.04). Finally, there were significant differences in coverage rates by therapeutic area (P < 0.001)—qualitatively dermatologic drugs were covered least and psychiatric drugs were covered the most.

TABLE 1.

Subgroup Analysis of Medicare Prescription Drug Coverage 1 Year Versus 3 Years After FDA Approval

| Year 1 | Year 3 | P Value (Year 1 vs. Year 3)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median % (IQR) | P Valuea | Median % (IQR) | P Valuea | |||

| Overall | n = 144 | 61 (39-90) | 79 (57-100) | < 0.001 | ||

| Approval year | 2006 (n = 20) | 59 (53-80) | 0.80 | 82 (65-100) | 0.18 | < 0.001 |

| 2007 (n = 14) | 61 (52-91) | 84 (66-100) | 0.009 | |||

| 2008 (n = 16) | 65 (25-75) | 71 (64-100) | < 0.001 | |||

| 2009 (n = 24) | 60 (33-80) | 75 (47-92) | < 0.001 | |||

| 2010 (n = 17) | 52 (27-73) | 70 (43-85) | 0.005 | |||

| 2011 (n = 26) | 70 (21-100) | 92 (65-100) | 0.03 | |||

| 2012 (n = 27) | 53 (36-100) | 70 (47-100) | < 0.001 | |||

| Biologic | Yes (n = 20) | 56 (48-62) | 0.27 | 70 (46-84) | 0.05 | 0.19 |

| No (n = 124) | 62 (37-93) | 81 (60-100) | < 0.001 | |||

| Protected class | Yes (n = 57) | 93 (62-100) | < 0.001 | 100 (82-100) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| No (n = 87) | 50 (29-62) | 66 (46-84) | < 0.001 | |||

| Orphan drug | Yes (n = 45) | 62 (43-92) | 0.51 | 79 (66-100) | 0.32 | < 0.001 |

| No (n = 99) | 58 (36-89) | 79 (52-100) | < 0.001 | |||

| Priority review | Yes (n = 60) | 75 (58-93) | < 0.001 | 84 (70-100) | 0.003 | < 0.001 |

| No (n = 84) | 51 (29-75) | 68 (46-99) | < 0.001 | |||

| Accelerated approval | Yes (n = 16) | 91 (62-94) | 0.04 | 100 (74-100) | 0.02 | 0.004 |

| No (n = 128) | 58 (37-79) | 75 (53-100) | < 0.001 | |||

| Therapeutic area | Autoimmune (n = 8) | 62 (53-73) | <0.001 | 60 (46-83) | < 0.001 | 0.88 |

| Cancer (n = 33) | 90 (62-100) | 100 (73-100) | 0.003 | |||

| CV/DM/lipids (n = 17) | 69 (32-78) | 84 (78-97) | < 0.001 | |||

| Dermatologic (n = 9) | 29 (0-46) | 41 (7-58) | 0.11 | |||

| ID (n = 18) | 65 (49-93) | 89 (62-100) | 0.005 | |||

| Neurologic (n = 14) | 64 (26-76) | 83 (61-100) | 0.003 | |||

| Psychiatric (n = 8) | 100 (64-100) | 100 (82-100) | 0.50 | |||

| Other (n = 37) | 44 (18-61) | 65 (40-77) | < 0.001 | |||

aKruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney tests.

bWilcoxon signed-rank test.

CV = cardiovascular; DM = diabetes mellitus; ID = infectious disease; IQR = interquartile range.

There were also significant differences in coverage between years 1 and 3 following approval for most therapeutic characteristics (Table 1), including nonprotected drug classes, standard and priority review pathways, accelerated approvals, and several therapeutic areas. For instance, among nonprotected drugs, the median proportion of plans with any coverage at 1 year following approval was 50% (IQR = 29%-62%) and 66% (IQR = 46%-84%) at 3 years (P < 0.001). Similarly, among medications for cardiovascular conditions, diabetes, and lipid control, the median proportion of plans with any coverage at 1 year was 69% (IQR = 32%-78%) and 84% (IQR = 78%-97%) at 3 years (P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between coverage of biologics at 1 and 3 years following approval.

Discussion

In this study, we used Medicare prescription drug benefit plan data to characterize rates of formulary coverage for novel therapeutic agents following FDA approval over a 7-year period. While most Medicare plans covered the majority of novel therapeutics approved by the FDA in the year following approval, drug coverage was heterogeneous, with potentially significant delays in access to some novel medications. Moreover, restrictions such as prior authorization and step therapy requirements were commonly used. Finally, multiple novel therapeutic characteristics—including CMS-protected status, FDA priority review and accelerated approval, and therapeutic area—were associated with higher rates of coverage.

Most Medicare plans covered the majority of novel therapeutics approved by the FDA after 1 year, but even more plans covered novel therapeutics by 3 years after approval. While CMS mandates review of new approvals within 180 days,9 it is clear that FDA drug approval does not guarantee insurer coverage, even after several years. This heterogeneous pattern has been described previously for medical technologies—procedures, devices, and drugs—covered by Medicare Parts A and B. In these cases, coverage may be determined by local private contractors by local coverage determinations,22,23 or CMS may issue national coverage determinations.15 This process leads to unpredictability for technology manufacturers and consumers. Recently, the FDA and CMS have instituted a parallel review process to coordinate Medicare Parts A and B coverage and FDA approval decisions for medical devices.24 As of 2017, 2 devices have successfully navigated the program, and there continue to be efforts to optimize program use.17,25 While insurer coverage is not required for clinical use, lack of coverage may be a significant barrier to widespread adoption. It may be worth considering the expansion of this parallel review program to include novel therapeutic agents that are expected to be covered as part of Medicare’s prescription drug benefit.

In this study, FDA priority review designation—most often reserved for drugs thought to be a “significant improvement” over existing therapy26—was associated with increased rates of insurer coverage. An association between coverage and FDA-accelerated approval—in which the FDA grants approval based on surrogate endpoints to speed drugs to market—was similarly noted. Because these pathways are intended for therapeutics of greater clinical potential importance, in some respects, our findings are reassuring. However, controversy over the accelerated approval pathway exists because it may require insurers to consider coverage of expensive medications before definitive evidence of clinical efficacy has been generated.11 In addition, there are concerns over whether evidence of clinical efficacy is being routinely generated following surrogate end-point-based approval.27-29 Given the trend towards increased insurer coverage of accelerated approvals, therapeutics in this pathway may benefit from use of coverage with evidence development requirements, ensuring that adequate evidence is generated after FDA approval to inform clinical decision making.

Likewise, drugs within CMS-protected classes achieved coverage at rates exceeding 90%, compared with 50% among nonprotected drug classes at 1 year after approval. This result is consistent with previous studies that showed high coverage rates of cancer therapeutics and psychotropics (including protected classes of anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics).30,31 Recently, there have been a number of proposals to reduce the number of protected classes, including a 2014 CMS proposal to eliminate protections for antidepressants, immunosuppressants, and eventually antipsychotic therapies.13 The proposal—which was ultimately withdrawn because of concerns regarding vulnerable populations32—cited anticompetitive insurer practices that limited effective choice and raised costs as a major impetus for the proposed changes. While the economic effect of such changes is beyond the scope of this study, the results suggest, not unexpectedly, that CMS-protected status is associated with higher coverage of novel therapeutics.

A large proportion of covered novel therapeutic agents were covered with restrictions, including prior authorization or step therapy requirements. Only 4% of drugs had universal unrestrictive coverage 3 years following approval, and these drugs were limited to antiretroviral HIV therapies. These utilization management strategies can influence patterns of therapeutic usage to control costs and incentivize use of safer, more effective medications.33 CMS provides broad latitude for such strategies according to “existing best practices.”9 These findings are consistent with a 2009 study of top-selling biologics, which showed that plans often use prior authorization and other cost-control measures.34 The common use of either step therapy or prior authorization suggests that plans are attempting to ensure that patients fulfill certain criteria or try alternatives before receiving novel therapeutics. Given the broad and sophisticated use of coverage restrictions, this may be an important area for regulatory review in the future.

Our analysis showed significant coverage variability for novel therapeutic agents, suggesting that patient access to new drugs is highly dependent on plan choice. While 90% of drugs in the sample were covered by at least 1 plan in the year after approval, few drugs were covered by every plan. By design, Medicare prescription drug plans incorporate free market features that ideally allow patients to choose the plan that best addresses their health care needs.35 However, in reality numerous and complex plan choices, limited by geography and existing medication needs, may complicate decision making,36 and studies have shown that patients have trouble predicting their health care use patterns for the coming year.37 Given that the drugs included in our study are new to clinical practice, it is unlikely that patients could predict need for these medications and plan accordingly. Some have suggested developing a standardized national formulary,38 a process that could offer significant advantages to patient access but would come at the expense of choice.

Policy Recommendations

Overall, our findings suggest a number of policy implications for drug makers, regulators, insurers, clinicians, and patients. First, while the majority of novel therapeutic agents are covered by Medicare prescription drug plans by the year following FDA approval, access to novel therapeutics appears to be largely dependent on plan choice. However, patients have limited ability to anticipate need for novel therapies, since these medications are new to the market. Moreover, many patients select neither the cheapest plans that fulfill their needs nor reassess their insurance plans following initial selection despite a number of tools that compare plans (such as Medicare Plan Finders).39,40 Several approaches have been suggested to improve patient plan selection, from changing the user interface of existing systems to creating novel online decision support tools.41,42 Reduction in the number of plan choices has also been shown to decrease cognitive overload and improve optimal plan choice.36,39,43 Regardless of broader changes to the insurance marketplace, our study underscores the importance of policies that promote annual reevaluation of plan choice as coverage evolves and new drugs are approved by the FDA and are covered, or not, by prescription drug plans.

Second, despite CMS-protected drug class designation, a number of insurers may still restrict drug access by using formulary utilization management tools. CMS currently places few limits on utilization management, mandating use of “existing best practices,” which creates an imprecise framework that could affect patient access.9 Because we found that coverage of novel therapeutics often occurs with step therapy or prior authorization requirements, future studies should evaluate these requirements in greater detail to determine if they are aligned with the letter and spirit of existing regulations.

Finally, there may be utility in creating a case-by-case mechanism to guarantee evaluation for coverage of novel therapeutics, a role that an expanded FDA-CMS parallel review process could fill.44,45 Parallel review is currently limited to medical devices seeking an expedited CMS national coverage determination for Medicare Part A or B. Expanding this program to include prescription drugs, provided that sufficient resources are made available to support such an effort, might not only streamline coverage determinations for prescription drugs, but also could incentivize evidence generation relevant to the Medicare beneficiary population, which is generally older, more often female, and affected by more comorbidities than the general population.46

Limitations

Our analysis has several limitations to consider. First, novel therapeutic agents represent a diverse set of medical technologies, and our attempts to group drugs may oversimplify complex approval pathways and use patterns. While coverage was evaluated at multiple time points and stratified by year of approval, we could not control for all temporal trends, such as changes in FDA, CMS, or commercial insurer policies. In addition, data are presented as proportions of the annual number of prescription drug plans but may not necessarily account for nonrandom variability in plan enrollment or benefit structure.

Second, we have defined restrictive coverage to exclude formulary tier, which determines patient cost sharing, because formularies have expanded the number of tiers from 4 to 5 or even 6 over the past decade. Therefore, tiering could not be accurately compared across the time period of our study.47

Third, this analysis may not be generalizable to non-Medicare prescription drug plans. Medicare, however, provides coverage for the largest number of beneficiaries in the United States, and its coverage policies have important implications for pharmaceutical and biologic manufacturers.

Finally, our analysis was limited to the use of Medicare formulary files, which may not include records for all plans, formularies, or novel therapeutic agents due to inaccuracies or delays in data reporting. However, Medicare records are well maintained, and our exclusion criteria were formulated to maintain external validity.

Conclusions

This study characterizes rates of Medicare prescription drug benefit plan coverage for novel therapeutic agents. The analysis underscores that, given the heterogeneity of plan coverage, patient access to medication is largely dependent on plan choice. Most Medicare plans covered the majority of novel therapeutics in the year following FDA approval, although often with coverage restrictions such as prior authorization or step therapy requirements. While certain therapeutic characteristics were associated with coverage, plans retained significant latitude to structure formularies to particular needs and markets. Policymakers may identify opportunities to improve and streamline regulation of this federal entitlement program.

APPENDIX A. Initially Excluded Drugs

| Brand Name | Generic Name | FDA Approval | Exclusion Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qutenza | Capsaicin | 11/16/2009 | Previously approved |

| Lumozyme | Glucosidase alfa2 | 5/24/2010 | Previously approved |

| Ammonia N13 | Ammonia | 8/23/2007 | Imaging agent |

| Lexiscan | Regadenoson | 4/10/2008 | Imaging agent |

| Eovist | Gadoxetate disodium | 7/3/2008 | Imaging agent |

| Adreview | Iobenguane | 9/19/2008 | Imaging agent |

| Ablavar | Gadofosveset trisodium | 12/22/2008 | Imaging agent |

| Datscan | Ioflupane i-123 | 1/14/2011 | Imaging agent |

| Gadavist | Gadobutrol | 3/14/2011 | Imaging agent |

| Amyvid | Florbetapir F 18 | 4/6/2012 | Imaging agent |

| Choline C11 | Choline C11 injection | 9/12/2012 | Imaging agent |

| Surfaxin | Lucinactant | 3/6/2012 | Pediatric indication |

| Anthelios SX | Avobenzone; ecamsule; octocrylene | 7/21/2006 | Over the counter |

| Belviq | Lorcaserin hydrochloride | 6/27/2012 | Weight loss medication |

| Mircera | Methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta | 11/14/2007 | NDC unmatched in database |

| Stendra | Avanafil | 4/27/2012 | NDC unmatched in database |

| Granix | Tbo-filgrastim | 8/29/2012 | NDC unmatched in database |

| Fycompa | Perampanel | 10/22/2012 | NDC unmatched in database |

| ------------- | Raxibacumab | 12/14/2012 | NDC unmatched in database |

| Neupro | Rotigotine | 5/9/2007 | Drug withdrawn |

| Iclusig | Ponatinib | 12/14/2012 | Drug withdrawn |

| Omontys | Peginesatide acetate | 3/27/2012 | Drug withdrawn |

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NDC = National Drug Code.

APPENDIX B. Excluded Therapies with Alternative Coverage Mechanism

| Brand Name | Generic Name | FDA Approval | Indication | Administration | Exclusion Reason |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lucentis | Ranibizumab | 6/30/2006 | Macular degeneration | Intravitreal | Part B |

| Soliris | Eculizumab | 3/16/2007 | Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria | IV infusion | Part B |

| Entereg | Alvimopan | 5/20/2008 | Aids recovery of bowel resection surgery | PO post-op | Part A |

| Cleviprex | Clevidipine | 8/1/2008 | Blood pressure control when oral therapy not feasible | IV infusion | Part B |

| Nplate | Romiplostim | 8/22/2008 | Idiopathic (immune) thrombocytopenic purpura | Subcutaneous | Part B |

| Lusedra | Fospropofol | 12/12/2008 | Sedation | IV infusion | Part B |

| Kalbitor | Ecallantide | 12/1/2009 | Hereditary angioedema | Subcutaneous | Part B |

| Xiaflex | Collagenase clostridium histolyticum | 2/2/2010 | Dupuytren’s disease | Injection | Part A/B |

| Asclera | Polidocanol | 3/30/2010 | Varicose veins | IV injection | Part A/B |

| Krystexxa | Pegloticase | 9/14/2010 | Hyperuricemia/gout | IV infusion | Part B |

| Adcetris | Brentuximab vedotin | 8/19/2011 | Hodgkin lymphoma (third-line agent) | IV infusion | Part B |

| Eylea | Aflibercept | 11/18/2011 | Macular degeneration | Intravitreal | Part B |

| Kyprolis | Carfilzomib | 7/20/2012 | Multiple myeloma (third-line agent) | IV infusion | Part B |

| Jetrea | Ocriplasmin | 10/17/2012 | Vitreomacular adhesion | Intravitreal | Part B |

FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IV = intravenous; PO = per oral.

References

- 1.U.S. Food & Drug Administration . Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. 2018. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 2.Califf RM, Sherman RE, Slavitt A. Knowing when and how to use medical products: a shared responsibility for the FDA and CMS. JAMA. 2016;316(23):2485-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Social Security Act. 42 USC 1395y §1862 (1)(A) . Exclusions from coverage and Medicare as a secondary payer. 2018. Available at: https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1862.htm. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2017 annual report of the boards of trustees of the federal hospital insurance and federal supplementary medical insurance trust funds. 2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2017.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 5.Neumann PJ, Divi N, Beinfeld MT, et al. Medicare’s national coverage decisions, 1999-2003: quality of evidence and review times. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(1):243-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Social Security Act. 42 USC 1395w-111 §1860D-11(i) . Subpart 2—prescription drug plans; PDP sponsors; financing. 2018. Available at: https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title18/1860D-11.htm. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 7.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Development & approval process (drugs). 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 8.U.S. Food and Drug Administration . Orphan Drug Act-relevant excerpts. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/ForIndustry/DevelopingProductsforRareDiseasesConditions/HowtoapplyforOrphanProductDesignation/ucm364750.htm. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Chapter 6—Part D drugs and formulary requirements. In: Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Manual. January 15, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Part-D-Benefits-Manual-Chapter-6.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 10.Drummond MF, Wilson DA, Kanavos P, et al. Assessing the economic challenges posed by orphan drugs. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2007;23(1):36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gellad WF, Kesselheim AS. Accelerated approval and expensive drugs— a challenging combination. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(21):2001-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kesselheim AS, Wang B, Franklin JM, et al. Trends in utilization of FDA expedited drug development and approval programs, 1987-2014: cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . CMS proposes program changes for Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug Benefit Programs for contract year 2015 (CMS-4159-P). Press release. January 6, 2014. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/cms-proposes-program-changes-medicare-advantage-and-prescription-drug-benefit-programs-contract-year. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 14.Garber AM. Evidence-based coverage policy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(5):62-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chambers JD, May KE, Neumann PJ. Medicare covers the majority of FDA-approved devices and Part B drugs, but restrictions and discrepancies remain. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1109-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basu S, Hassenplug JC. Patient access to medical devices—a comparison of US and European review processes. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):485-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mezher M. FDA and CMS parallel reviews of devices to continue. October 21, 2016. Available at: http://www.raps.org/Regulatory-Focus/News/2016/10/21/26052/FDA-and-CMS-Parallel-Reviews-of-Devices-to-Continue/. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) . Program for parallel review of medical devices. Fed Regist. 2016;81(205):73113-73115. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/24/2016-25659/program-for-parallel-review-of-medical-devices. Accessed October 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messner D, Tunis S. Current and future state of FDA-CMS parallel reviews. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(3):383-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, et al. Regulatory review of novel therapeutics—comparison of three regulatory agencies. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):2284-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information Files. Database. 2006-2015. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/NonIdentifiableDataFiles/PrescriptionDrugPlanFormularyPharmacyNetworkandPricingInformation Files.html. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 22.Foote SB, Wholey D, Rockwood T, et al. Resolving the tug-of-war between Medicare’s national and local coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;23(4):108-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foote SB, Halpern R, Wholey DR. Variation in Medicare’s local coverage policies: content analysis of local medical review policies. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(3):181-87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridge JR, Statz S. Exact sciences’ experience with the FDA and CMS parallel review program. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(9):1117-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mezher M. FDA, CMS: second parallel review decision ever for NGS test. December 1, 2017. Available at: https://www.raps.org/regulatory-focus%E2%84%A2/news-articles/2017/12/fda,-cms-second-parallel-review-decision-ever-for-ngs-test. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 26.U.S Food and Drug Administration . Guidance for industry. Expedited programs for serious conditions–drugs and biologics. May 2014. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM358301.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 27.Pease AM, Krumholz HM, Downing NS, et al. Postapproval studies of drugs initially approved by the FDA on the basis of limited evidence: systematic review. BMJ. 2017;357:j1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naci H, Smalley KR, Kesselheim AS. Characteristics of preapproval and postapproval studies for drugs granted accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration. JAMA. 2017;318(7):626-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beaver JA, Howie LJ, Pelosof L, et al. A 25-year experience of US Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval of malignant hematology and oncology drugs and biologics: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(6):849-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowman J, Rousseau A, Silk D, et al. Access to cancer drugs in Medicare Part D: formulary placement and beneficiary cost sharing in 2006. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(5):1240-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huskamp HA, Stevenson DG, Donohue JM, et al. Coverage and prior authorization of psychotropic drugs under Medicare Part D. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58 (3):308-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare program; contract year 2016 policy and technical changes to the Medicare Advantage and the Medicare prescription drug benefit programs; final rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(29):7912-7966. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-02-12/pdf/2015-02671.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer MA, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, et al. Medicaid prior-authorization programs and the use of cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(21):2187-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang S-Y, Haas JS, Phillips KA. Medicare formulary coverage for top-selling biologics. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27(12):1082-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McFadden D. Free markets and fettered consumers. Am Econ Rev. 2006;96(1):3-29. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanoch Y, Rice T, Cummings J, et al. How much choice is too much? The case of the Medicare prescription drug benefit. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(4):1157-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou C, Zhang Y. The vast majority of Medicare Part D beneficiaries still don’t choose the cheapest plans that meet their medication needs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(10):2259-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huskamp HA, Keating NL. The new Medicare drug benefit: formularies and their potential effects on access to medications. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):662-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heiss F, Leive A, McFadden D, et al. Plan selection in Medicare Part D: evidence from administrative data. J Health Econ. 2013;32(6):1325-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han J, Urmie J. Medicare Part D beneficiaries’ plan switching decisions and information processing. Med Care Res Rev. March 1, 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martino SC, Kanouse DE, Miranda DJ, et al. Can a more user-friendly Medicare plan finder improve consumers’ selection of Medicare plans? Health Serv Res. 2017; 52(5):1749-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinaiko AD, Ross-Degnan D, Soumerai SB, et al. The experience of Massachusetts shows that consumers will need help in navigating insurance exchanges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):78-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Handel BR, Kolstad JT. Health insurance for “ humans”: information frictions, plan choice, and consumer welfare. Am Econ Rev. 2015;105(8):2449-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messner DA, Mohr P, Towse A. Futurescapes: evidence expectations in the USA for comparative effectiveness research for drugs in 2020. J Comp Eff Res. 2015;4(4):385-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baird L, Banken R, Eichler HG, et al. Accelerated access to innovative medicines for patients in need. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96(5):559-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission . A data book: healthcare spending and the Medicare program. June 2017. Available at: http://www. medpac.gov/docs/default-source/data-book/jun17_databookentirereport_sec.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- 47.Hoadley JF, Cubanski J, Neuman P. Medicare’s Part D drug benefit at 10 years: firmly established but still evolving. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1682-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]