Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Generic drugs are bioequivalent and cost-effective alternatives to brand drugs. In 2014, $254 billion was saved because of the use of generic drugs in the United States.

OBJECTIVE:

To critically assess evidence on the association between patient characteristics and generic drug use in order to inform the development of educational outreach for improving generic drug use among patients.

METHODS:

We systematically searched the literature between January 2005 and December 2016 using PubMed, Web of Science, Ovid MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and EBSCO IPA-MEDLINE for potentially relevant studies. The titles and abstracts of identified articles were assessed independently by 2 reviewers. Titles and abstracts that were not written in English, were published before 2005, were not empirical, did not contain sociodemographic data, or were not policy or methodologically relevant to generic drug use were excluded. Data were pooled in a meta-analysis using the RStudio software to assess the association of patient-related factors with generic drug use.

RESULTS:

Our searches resulted in 11 articles on patient-level factors, and 6 of these articles had sufficient information to conduct meta-analyses in the domains of patients’ gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income. Quantitative analysis indicated that no differences in generic drug use existed between subgroups of patients defined by gender, age, or race/ethnicity. However, patients with lower income (i.e., < 200% federal poverty level [FPL]) were more likely to use generic drugs than those with higher income (≥ 200% FPL; pooled OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.15-1.52). Heterogeneity was high (I2 > 75%) for all analyses but income.

CONCLUSIONS:

Patients with lower income were more likely to use generic drugs, whereas evidence was heterogeneous regarding an association between generic drug use and gender, age, or race/ethnicity. Educational outreach targeting patients with higher incomes to understand their perspectives in generic drugs may help improve generic drug use within that population.

What is already known about this subject

Over the past 10 years, the rate of increase in health care spending has declined, which has been primarily attributed to the increased use of generic drugs.

Patient characteristics or preferences such as age, educational levels, perceptions about the disease, generic drug information, misconceptions, and negative perceptions regarding generic medicines influence the use of generics.

What this study adds

This meta-analysis assessed the evidence of 6 studies in the domains of patients’ gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income and examined whether these patient characteristics are associated with generic use.

We found that patients with lower income were more likely to use generic drugs than those with higher income.

Patients’ gender, age, and race/ethnicity showed no statistically significant association with the use of generic drugs.

Health care spending in the United States has been increasing at dramatic rates. In 2001, U.S. health care spending was $1.5 trillion, increasing to $2.9 trillion in 2013.1 Increased use and the high cost of prescription drugs have played a large role in rising health care costs. For example, in 2014 prescription drugs represented 9.83% of total health care spending, but as of 2015, prescription drugs have increased to 10.13% of total health care spending.2 Slowing the growth curve for prescription drug spending is a national priority, particularly given that per capita spending on prescription drugs in the United States is more than 2-fold higher than the average for other advanced industrialized nations.3,4

Generic drugs can play an important role in controlling drug spending. Generic drugs account for roughly 90% of all dispensed prescriptions in the United States, yet they account for only 28% of prescription drug spending.5 The estimated savings attributed to generic drugs was $254 billion in 2014.6 Over the past 10 years, the rate of increase in health care spending has declined, which has been primarily attributed to the increased use of generic drugs.7 Use of generics instead of brand drugs has been recognized as an important and effective tool to control rising prescription drug costs.4,8

While in some cases brand drugs represent the best treatment option for an individual patient, in many cases when a brand drug is used, a lower-cost generic could have been directly substituted (i.e., a brand drug replaced with a generic of the same drug) or therapeutically substituted (i.e., a brand drug replaced with a generic of a different but therapeutically similar drug). But some patients and providers are resistant to generic substitution. For example, a 2016 national consumer survey found that 13% of respondents believed that brand drugs are more effective than generic drugs, and 20% of respondents believed that generic drugs have different side effects than brand drugs.9 In a parallel survey of physicians, 11% of physicians expressed negative perceptions about the efficacy of generic drugs and 27% believed they caused more adverse effects.10 Further, an estimated 5% of prescription drugs are dispensed “as written” with brand product due to the active requests of patients and physicians, contributing annually almost $1.2 billion in excess drug costs.11

In a recent systematic review, 6 key domains were identified to influence generic drug use.12 These include Sociodemographic Factors, Formulary Management and Cost Control Factors, National and State Health Insurance Policy, Promotional Activities, Educational Activities, and Technology. Among these key domains, the evidence is most robust surrounding providers and patients. For example, providers sometimes believe that a key product or disease features are important in the choice to use a brand drug versus a generic drug. These factors are sometimes reflected in prescribers’ decision making and, in some instances, the use of the brand drug is promoted by professional associations such as the American Academy of Neurology, which posits that brand drugs should be used over generics.13 In general, brand drug use tends to be higher among products such as sterile injectables, specialty drugs, atypical antipsychotics, biologics, and narrow therapeutic index drugs such as antiepileptics, thyroid drugs, and immunosuppressant drugs.14-21

Patient characteristics or preferences that can influence generic drug use include age, educational levels, perceptions about the disease, generic drug information, misconceptions, and negative perceptions regarding generic medicines. This evidence, however, is largely qualitatively based, and there are important inconsistencies in how various patient factors influence generic drug use.22-25 To our knowledge, no quantitative analyses summarizing this evidence exist. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis focused on how different patient-related factors influence generic drug use. Specifically, we examined whether patients’ gender, age, income, and race/ethnicity are associated with generic drug use.

Methods

Literature Search

This literature review was part of a larger systematic review of factors influencing generic drug use.12 We systematically searched the literature between January 2005 and December 2016 using PubMed, Web of Science, Ovid MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and EBSCO IPA-MEDLINE for potentially relevant studies. The titles and abstracts of the identified articles were reviewed by 2 independent reviewers to look for potential information specific to this topic. Articles assessing how sociodemographic factors influence generic drug use were further considered. The conduct of the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidance.26

Inclusion Criteria

The identified abstracts were assessed by 2 reviewers, who used the following inclusion criteria: (a) published in English; (b) contained patient sociodemographic data; and (c) presented empirical analysis. Articles were excluded if the abstract failed to meet any of the inclusion criteria. Full-text articles of all eligible abstracts were obtained and further assessed for quantitative data on subgroups of patients defined by gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income. Articles not containing enough quantifiable information targeted to our patient-related domains were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Data Abstraction

The following data were abstracted from each study, including information on generalizability, data source, sample size, total number of different patient subgroups, and total number of different subgroups using generics from each study. We abstracted the percentage of different subgroups and their generic use, as well as quantitative values, such as odds ratios (ORs), when available. Initially, all the information related to generic use among subgroups of patients defined by gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income were abstracted. Each subgroup was then handled separately, allowing inclusion of some studies multiple times across subgroups.

Variables under each subgroup were inconsistent across the literature. For variables that were categorized differently across studies, we pooled data to reflect more consistent groups. For example, the income of different groups was presented in dollar values across the studies, and dollar values were inconsistent across the identified papers. We merged these different income values by standardizing the numbers into corresponding federal poverty levels (FPLs). For studies with multiple smaller categories, we summed dollar values and then counted the total number of people in the study as < 200% FPL as opposed to those ≥ 200% FPL.

Statistical Analysis

The meta package in RStudio software version 3.3.2 was used for conducting statistical analyses (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). ORs were used as a common measure of association between generic drug use and subgroups of patients defined by gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income. The ORs, along with a 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between generic drug use and subgroups of patients, were calculated for each included study and then pooled by demographic subgroup. Studies identified for meta-analyses were conducted by different investigators in different settings. All studies are not functionally equivalent; hence, we cannot assume a common effect size. For this reason, we specified all meta-analyses as a random effects model.27

Heterogeneity of each meta-analysis was tested by using the I2 statistic.28 An I2 value of 0% indicates “no heterogeneity,” whereas 25% is “low,” 50% is “moderate,” and 75% is “high” heterogeneity.29 Funnel plots were used to estimate possible publication bias caused by the tendency of published studies to be negative.30

Results

Included Studies

The larger review of factors influencing generic drug use yielded 307 articles after removing duplicates. Of these, 71 full-text articles were retained. Finally, 11 of these articles provided relevant information addressing the relationship between 1 or more sociodemographic factors and generic drug use.31-41 Six of these articles had sufficient information to include in meta-analyses for the domains of patients’ gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income.31-36 Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of our search results.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Study Characteristics

The identified studies provided quantitative information on the domains of patients’ gender, age, race/ethnicity, and income. The main characteristics of all 11 potential studies are presented in Table 1. This table details the study characteristics, the overall conclusions for each of the characteristics that were reported in the study, and the quantitative findings when reported. Out of these 11 studies, 6 studies provided sufficient quantitative information to conduct further analyses. All 6 studies provided quantitative information of generic drug use among males and females. Each study provided the information on the data source and total sample size of the study.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in Meta-analyses

| Study | Generalizability | Data Source | Sample Sizea | Use of Genericb | Reported OR (95% CI) | Calculated OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender and generic drug use (ref: male) | ||||||

| Chen (2008)31 | Kids | MEPS | 24,465 | Female ↑ | 1.36 (1.08-1.73) | 1.19 (1.14-1.26) |

| Gagne (2013)32 | Older adults | CVS and Medicare | 36,832 | Female ↓ | 0.83 (0.78-0.87) | 0.83 (0.79-0.88) |

| Gatwood (2011)33 | Adults Caucasian | University of Michigan | 311 | Female ↔ | – | 1.11 (0.63-1.96) |

| Zhang (2012)35 | Elderly Medicare beneficiaries | U.S. Medicare Part D data | 347,653 | Female ↔ | 1.00 (0.98-1.03) | 1.00 (0.98-1.02) |

| Federman (2006)34 | Adults | 2001 MCBS | 1,710 | Female ↔ | – | 1.10 (0.86-1.41) |

| Li (2014)36 | Adults | Truven Health Analytics | 26,033 | Female ↓ | – | 0.64 (0.60-0.68) |

| Omojasola (2014)37 | Adults | The University of Texas | 520 | Female ↑ | 1.60 (1.10-2.50) | – |

| Cox (2007)38 | Adults | Commercially insured market | 395,000 | Female ↑ | – | – |

| Mager (2007)40 | Adults | Express Scripts | 3,979 | Female ↑ | – | – |

| Shrank (2009)39 | Adults | National mailed survey | 2,500 | Female ↓ | – | – |

| Age and generic drug use | ||||||

| Gagne (2013)32 | Older adults | CVS and Medicare | 24,465a | 65-74 years (ref) | – | – |

| ≥ 75 years ↑ | – | 1.25 (1.18-1.31) | ||||

| Zhang (2012)35 | Elderly Medicare beneficiaries | U.S. Medicare Part D data | 347,653 | 65-74 years (ref) | – | – |

| ≥ 75 years ↓ | – | 0.75 (0.73-0.76) | ||||

| Federman (2006)34 | Adults | 2001 MCBS | 242,691 | 65-74 years (ref) | – | – |

| ≥ 75 years ↔ | – | 0.82 (0.65-1.04) | ||||

| Gatwood (2011)33 | Adults Caucasian | University of Michigan | 311 | < 30 (ref) | – | – |

| 30-49 ↔ | 1.03 (0.37-2.91) | – | ||||

| 50-64 ↓ | 2.79 (1.08-7.20) | – | ||||

| > 64 ↔ | 0.95 (0.30-3.06) | – | ||||

| Income and generic drug use | ||||||

| Chen (2008)31 | Kids | MEPS | 24,465a | Income ≥ 200%-400% FPL (ref) | – | – |

| Income < 200% FPL ↑ | – | 1.29 (1.23-1.36) | ||||

| Gatwood (2011)33 | Adults Caucasian | University of Michigan | 311 | Income ≥ 200% FPL (ref) | – | – |

| Income < 200% FPL ↑ | – | 2.20 (1.21-4.02) | ||||

| Federman (2006)34 | Adults | 2001 MCBS | 242,691 | Income ≥ 200% FPL (ref) | – | – |

| Income < 200% FPL ↔ | – | 1.27 (1.00-1.60) | ||||

| Zhang (2012)35 | Elderly Medicare beneficiaries | U.S. Medicare Part D data | 347,653 | Income < $25K (ref) | – | – |

| $25K-$35K ↓ | 0.94 (0.91-0.97) | – | ||||

| $35K-$45K ↓ | 0.92 (0.88-0.97) | – | ||||

| > $45K ↓ | 0.86 (0.81-0.91) | – | ||||

| Omojasola (2014)37 | Adults | The University of Texas | 520 | Income > $10K (ref) | – | – |

| Income $10K-$20K ↔ | 1.40 (0.90-2.30) | – | ||||

| Income $20K-$30K ↑ | 1.80 (1.10-2.70) | – | ||||

| Race/ethnicity and generic drug use | ||||||

| Chen (2008)31 | Kids | MEPS | 24,465a | White (ref) | – | – |

| Hispanic ↔ | 1.03 (0.87-1.21) | 1.19 (1.12-1.27) | ||||

| Black ↔ | 1.15 (0.92-1.44) | 1.26 (1.17-1.36) | ||||

| Asian ↑ | 1.66 (1.07-2.57) | 1.63 (1.31-2.02) | ||||

| Gagne (2013)32 | Older adults | CVS and Medicare | 36,832 | White (ref) | – | – |

| Hispanic ↔ | – | 1.10 (0.76-1.61) | ||||

| Black ↑ | – | 1.18 (1.03-1.36) | ||||

| Asian ↔ | – | 0.62 (0.38-1.01) | ||||

| Zhang (2012)35 | Elderly Medicare beneficiaries | U.S. Medicare Part D data | 347,653 | White (ref) | – | – |

| Hispanic ↔ | 1.10 (1.02-1.19) | 0.99 (0.92-1.07) | ||||

| Black ↓ | 0.80 (0.75-0.85) | 0.90 (0.84-0.96) | ||||

| Asian ↓ | 0.72 (0.63-0.81) | 0.58 (0.51-0.65) | ||||

| Federman (2006)34 | Adults | 2001 MCBS | 242,691 | White (ref) | – | – |

| Hispanic ↑ | – | 0.56 (0.36-0.84) | ||||

| Asian ↓ | – | 0.03 (0.02-0.03) | ||||

| Black ↔ | – | 0.89 (0.62-1.30) | ||||

| Omojasola (2014)37 | Adults | The University of Texas | 520 | White (ref) | 0.89 | – |

| Hispanic ↔ | 1.50 (0.60-3.70) | – | ||||

| Black ↔ | 0.90 (0.40-2.20) | – | ||||

| Asian ↔ | 0.80 (0.30-2.40) | – | ||||

| Chen (2008)41 | Adult Caucasians | MEPS | 10,416 | Caucasian (ref) | – | – |

| Hispanic ↑ | – | – | ||||

| Black ↑ | – | – | ||||

Note: A dash (-) in a cell = not enough quantifiable data.

aNumber of prescriptions.

b↑ Increase, ↓ Decrease, ↔ No significant relation as lower bound of 95% CI is < 1 and upper bound is > 1.

CI = confidence interval; CVS = CVS Caremark; FPL = federal poverty level; MCBS = Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey; MEPS = Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; OR = odds ratio; ref = reference.

Of the 6 studies, 4 studies provided data on race/ethnicity and generic drug use. Table 1 reports the sample size, data source, reported ORs, and calculated ORs for generic drug use by different race/ethnicity categories. For income and age, the sample size, data source, reported ORs, calculated ORs, and level of generic drug use by these subgroups are also presented in Table 1. These variables represent the total reported quantitative information identified from the selected studies.

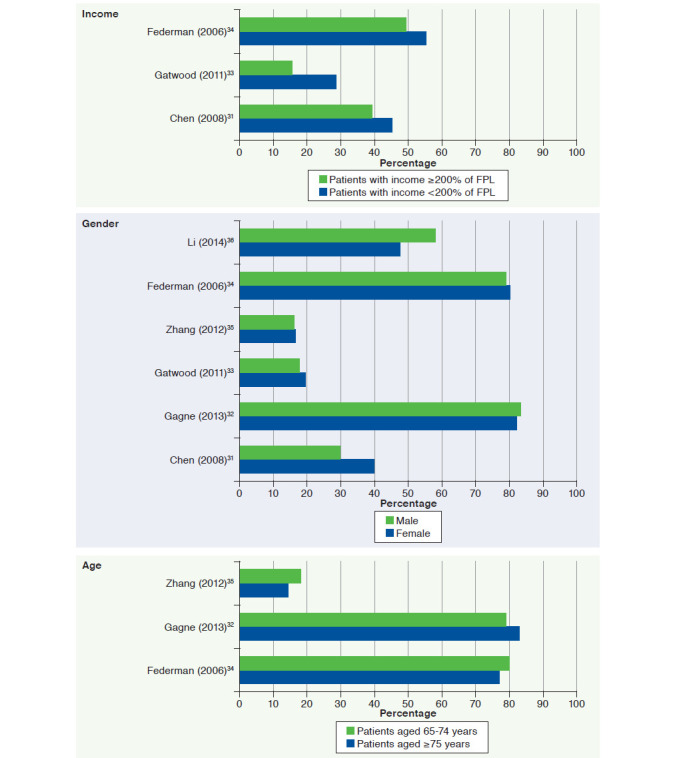

A graphical representation of each individual study and an aggregated estimate for each subgroup are shown in Figure 2. Notably, there was high variability in the proportion of generic drug use across studies and subgroups. For example, there were inconsistent data across studies for age and income; as a result, data were categorized into binary subgroups for certain studies.

FIGURE 2.

Generic Drug Use by Subgroups

Meta-analysis of Generic Drug Use and Subgroups of Patients

Three articles included in the meta-analyses reported the use of generic drugs and income of participants. Random effects meta-analyses showed that patients with lower income (i.e., < 200% FPL) were more likely to use generic drugs than those with higher income (≥ 200% FPL; pooled OR = 1.32, 95% CI = 1.15-1.52). The I2 value of 34.30% indicates the presence of relatively low heterogeneity (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Meta-analyses of Generic Drug Use and Subgroups of Patients (Forest Plots)

For gender and age, the meta-analysis did not identify subgroups that were more likely to use generic drugs. Six studies reported the use of generics among males and females. The pooled OR = 1.0 (95% CI = 0.77-1.29), indicating the absence of an association between generic drug use and patients’ gender. For age, there were 3 articles, with information about generic drug use among older adults. Participants aged ≥ 75 years had a similar pooled likelihood of using generics compared with adults 65-74 years, OR = 0.92 (95% CI = 0.61-1.38; Figure 3).

The association of generic drug use by subgroups of race/ethnicity was also examined. Four studies reported the use of generic drugs by groups of different races. Random effects meta-analysis showed no significant difference between blacks and whites in use of generic drugs (OR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.86-1.33). Similarly, comparisons of Hispanics with whites (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.83-1.20), as well as Asians with whites (OR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.39-1.82) showed no statistically significant differences in terms of generic drug use. Finally, we examined the use of generic drugs by the white population compared with all other races and found no statistically significant difference (pooled OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.83-1.83; Figure 3).

Heterogeneity was examined in all the quantitative analyses. Heterogeneity was high (I2 > 75%) for all analyses, except for income. High heterogeneity indicates high variation in study outcomes between the identified studies (Figure 3). For this reason, pooled estimates should be interpreted cautiously.

Publication Bias

The number of studies included in our meta-analysis was low (< 10); hence, it was not feasible to use the tests for funnel plot asymmetry. Because of this constraint of sample size, we cannot derive any valid interpretation regarding the publication bias through funnel plots.42

Discussion

Growing health care spending can be managed in part by promoting generic drug use. Understanding factors that influence generic drug use can help guide outreach programs that aim to improve generic drug use. These meta-analyses were conducted systematically to evaluate the association between generic drug use and patient-related factors. The results showed that there was a significant association between patient income and generic drug use. This finding suggests that people with lower income use more generic drugs compared with their higher-income counterparts.

We recognize that other factors such as state generic substitution laws,43 a patient’s disease state or education level, and a provider’s preference may affect a patient’s generic drug use. However, we did not have access to those data for this meta-analysis. One reason that patients choose generic drugs over brand drugs could be the lower price of the generics. People with lower income may be more price sensitive.44 Another reason for using generic drugs among lower-income populations could be the generic drug promotion by their insurances, such as Medicaid programs. Some Medicaid programs have adopted successful strategies for promoting the dispensing of low-cost generics to contain drug costs,45 although some studies have found higher brand drug use among Medicaid recipients because of states’ limited ability to force generic substitution.46

Although the results showed that there are statistically significant differences in generic drug use among subgroups by income, there are previous studies where the majority of participants with higher income stated that they “would rather take a generic than a brand name drug” compared with lower-income participants.47 This attitude toward generic drugs among the lower-income population could be because of the negative perception regarding the safety and effectiveness of generic drugs. This negative perception has been recorded in previous work. In a study of low-income, racially and ethnically mixed seniors, 1 in 4 believed that generics are not as effective as brands, and 1 in 5 had safety concerns.48 Patients’ perceptions about generics can be a key factor in terms of lower use of generics. Along with patients’ perceptions, health care providers may also share the negative perception toward generic drugs regarding their safety and quality.49 A widely held belief about generic drugs is that generics are not as effective as brands, although both are pharmaceutically equivalent.50 This negative view or differential perceptions of this view across subgroups could be a determining factor for the lower use of generics.

The association of generic drug use and other patient-related factors were also examined for age, gender, and race/ethnicity. We found there was no statistically significant association between these factors and the use of generics. While not statistically significant in pooled analyses, this is somewhat contrary to previous studies of patients’ perceptions of generics. For example, a previous study among the population of Alabama’s black belt region found perceptions that generics are less potent than brand medications and require higher doses, and therefore result in more side effects. This study also found perceptions that generics are not “real” medicine, that generics are for minor but not serious illnesses, and that poor people are forced to “settle” for generics.50

Earlier qualitative findings also showed that negative perceptions of generic drugs are greater among older adults, minorities, and people with low socioeconomic status and health literacy.51 Less generic drug use among this population could be the result of some common misconceptions about generics, such as that they are less effective, take longer to start working, are not safe, and are manufactured in substandard facilities.52 Further work is needed to explore the relationship between health insurance, income, patients’ perception, and generic drug use.

Negative perceptions about generic drugs can act as a major barrier to the public’s acceptance and hence limit the use of generics.53 Negative perceptions about generic drugs is a global phenomenon. Several studies including clinical trials have provided evidence that brand drugs and generics are equivalent in terms of safety and efficacy.54,55 However, studies found that for serious illness, Australians and Portuguese prefer brand drugs over the generics and do not believe that generics are as good as brands.56,57

Lack of communication with providers and a knowledge gap in generic drugs could be contributing factors to these negative perceptions. Because of the knowledge gaps, some consumers believe that generic drugs are not the “real thing.”50 A previous study found that elderly hospitalized New Yorkers with low health literacy hold more negative beliefs about generics if they are nonwhite.51 This negative perception is not only present among lay persons, but a significant proportion of doctors and pharmacists have a view that generics compared with brands are less effective, are of inferior quality, and can contribute to more side effects.53 Older physicians (> 55 years) have more negative perceptions about generic drugs compared with younger physicians, are less likely to use generic drugs, and are less likely to recommend generics to their family members.58 These negative perceptions and attitude toward generics may be responsible for some brand prescribing.

Heterogeneity was high (I2 > 75%) for all analyses (age, gender, race/ethnicity) but income. One reason behind the presence of high heterogeneity could be the presence of a small number of studies in each meta-analysis.59 Studies identified and selected in the quantitative analysis have different settings and objectives, as well as different populations, drugs/diseases, and outcomes, which likely contributed to the high heterogeneity in our analyses.60 For example, in our quantitative analysis for income, 2 studies were about generic drug discount programs, which may lead to more income effect built into the generic drugs for these 2 studies compared with the third study assessing general generic drug use without any financial incentives built in. Caution should be taken in interpreting the result because of high heterogeneity and presence of few studies in each analysis.61

Educating patients and communicating with them about the differences between brands and generics may improve generic drug uptake. Our finding suggested that individuals with higher income may use fewer generic drugs compared with those with lower income. This could suggest looser drug utilization controls among insurance plans prevalent among those with higher income, or differential perceptions by income status. Most likely, higher-income subgroups simply have greater economic means to pay for higher cost sharing of branded products.

Policymakers can design and tailor specific educational outreach targeting different patient perceptions and characteristics to promote the use of generic drugs. Misconceptions about generic drugs can be overcome through the active involvement of health care professionals. Active involvement and communication by health care professionals such as pharmacists can increase patient acceptability of generic drugs.47 Educational interventions also have been proven to improve physicians’ knowledge about generic drugs.62 While not a subject of this study, physician perceptions may be a factor that ultimately contributes to patients’ use of generics. By removing the misconception from both patient and provider ends, use of generics can be increased, which, in turn, will contribute to lowering health care spending.

Limitations

This analysis has several potential limitations. First, we may have missed articles that could be relevant, including in the gray literature. For example, our systematic review and meta-analysis included published studies (extracted from 5 individual search engines) during January 2005 and December 2016, so we may have missed studies that were published before this time period and not available from the search engines used. While our analysis was based on a rigorously conducted systematic review, missing studies could still be an issue.

Second, our sample size for quantitative analysis was small. We have many studies that did not provide any quantitative data and could not be analyzed. Because of the small number of studies (< 10) included in the meta-analysis, we were not able to conduct the test for forest plot asymmetry. Therefore, our results may be biased by the characteristics of the studies we analyzed and further affect generalizability of the study results. Finally, heterogeneity was high (I2 > 75%) for all analyses but income. There is a risk of bias due to high heterogeneity in our study.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggested that lower income is associated with generic drug use, and people with lower income use generics more. While analysis of subgroups other than income did not identify differential use of generics, there was high heterogeneity across these studies. Educational outreach targeting patients with higher incomes to understand their perspectives on generic drugs might help improve generic drug use.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2016 highlights. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 2.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Historical national health expediture data. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 3.Schoenbaum SC, Weinbaum I, Schoen C, Shih A, Guterman S, Davis K.. Slowing the growth of U.S. health care expenditures: what are the options? The Commonwealth Fund. January 1, 2007. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2007/jan/slowing-the-growth-of-u-s--health-care-expenditures--what-are-the-options. Accessed February 17, 2018.

- 4.Kesselheim AS, Avorn J, Sarpatwari A.. The high cost of prescription drugs in the United States: origins and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2016;316(8):858-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/MCBS/index.html?redirect=/MCBS. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 6.Generic Pharmaceutical Association. Generic drug savings in the U.S. 2013. Available at: http://www.gphaonline.org/media/cms/2013_Savings_Study_12.19.2013_FINAL.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 7.U.S. Government Accountability Office. Drug pricing: research on savings from generic drug use. 2012. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-12-371R. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 8.Andersson K, Sonesson C, Petzold M, Carlsten A, Lönnroth K.. What are the obstacles to generic substitution? An assessment of the behaviour of prescribers, patients and pharmacies during the first year of generic substitution in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol. 2005;14(5):341-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kesselheim AS, Gagne JJ, Franklin JM, et al. Variations in patients’ perceptions and use of generic drugs: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):609-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kesselheim AS, Gagne JJ, Eddings W, et al. Prevalence and predictors of generic drug skepticism among physicians: results of a national survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):845-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Donohue JM, Lave JR, O’Donnell G, Newhouse JP.. The effect of Medicare Part D on drug and medical spending. New Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):52-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard JN, Harris I, Frank G, Kiptanui Z, Qian J, Hansen R.. Influencers of generic drug utilization: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. August 4, 2017 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaw SJ, Hartman AL.. The controversy over generic antiepileptic drugs. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2010;15(2):81-93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mark TL, Kassed C, Levit K, Vandivort-Warren R.. An analysis of the slowdown in growth of spending for psychiatric drugs, 1986-2008. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(1):13-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ventimiglia J, Kalali AH.. Generic penetration in the retail antidepressant market. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(6):9-11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. Medicines use and spending shifts. April 2015. Available at: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/medicines-use-and-spending-shifts-in-the-us-in-2014.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- 17.Woodcock J, Wosinska M.. Economic and technological drivers of generic sterile injectable drug shortages. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93(2):170-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu HT, Samuel DR.. Limited options to manage specialty drug spending. Res Brief. 2012;(22):1-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenderts S, Kalali AH, Buckley P.. Generic penetration in the retail atypical antipsychotic market. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2010;7(3):9-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarpatwari A, Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS.. Paying physicians to prescribe generic drugs and follow-on biologics in the United States. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carbon M, Correll CU.. Rational use of generic psychotropic drugs. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(5):353-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Håkonsen H, Toverud E-L.. A review of patient perspectives on generics substitution: what are the challenges for optimal drug use. GaBi Journal. 2012;(1):28-32. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272656515_A_review_of_patient_perspectives_on_generics_substitution_What_are_the_challenges_for_optimal_drug_use. Accessed February 12, 2018.

- 23.Alrasheedy AA, Hassali MA, Stewart K, Kong DCM, Aljadhey H, Ibrahim MIM, Al-Tamimi S.. Patient knowledge, perceptions, and acceptance of generic medicines: a comprehensive review of the current literature. Patient Intelligence. 2014;6:1-29. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261411413_Patient_knowledge_perceptions_and_acceptance_of_generic_medicines_a_comprehensive_review_of_the_current_literature. Accessed February 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunne SS, Dunne CP.. What do people really think of generic medicines? A systematic review and critical appraisal of literature on stakeholder perceptions of generic drugs. BMC Med. 2015;13:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrank WH, Stedman M, Ettner SL, et al. Patient, physician, pharmacy, and pharmacy benefit design factors related to generic medication use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1298-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR.. Chapter 13, Fixed-effect versus random-effects models. In: Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR.. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2009:77-85. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG.. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melsen WG, Bootsma MC, Rovers MM, Bonten MJ.. The effects of clinical and statistical heterogeneity on the predictive values of results from meta-analyses. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(2):123-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C.. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen AY, Wu S.. Dispensing pattern of generic and brand-name drugs in children. Ambul Pediatr. 2008;8(3):189-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gagne JJ, Polinski JM, Kesselheim AS, et al. Patterns and predictors of generic narrow therapeutic index drug use among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1586-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gatwood J, Tungol A, Truong C, Kucukarslan SN, Erickson SR.. Prevalence and predictors of utilization of community pharmacy generic drug discount programs. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(6):449-55. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.6.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Federman AD, Halm EA, Zhu C, Hochman T, Siu AL.. Association of income and prescription drug coverage with generic medication use among older adults with hypertension. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(10):611-18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Gellad WF, Zhou L, Lin YJ, Lave JR.. Access to and use of $4 generic programs in Medicare. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1251-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Stürmer T, Brookhart MA.. Evidence of sample use among new users of statins: implications for pharmacoepidemiology. Med Care. 2014;52(9):773-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Omojasola A, Hernandez M, Sansgiry S, Paxton R, Jones L.. Predictors of $4 generic prescription drug discount programs use in the low-income population. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2014;10(1):141-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox ER, Kulkarni A, Henderson R.. Impact of patient and plan design factors on switching to preferred statin therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(12):1946-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(3):332-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mager DE, Cox ER.. Relationship between generic and preferred-brand prescription copayment differentials and generic fill rate. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(6 Pt 2):347-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen J, Rizzo JA.. Racial and ethnic disparities in antidepressant drug use. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2008;11(4):155-65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Agnew-Blais J, et al. State generic substitution laws can lower drug outlays under Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1383-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jones E, Chern WS, Mustiful BK.. Are lower-income shoppers as price sensitive as higher-income ones?: A look at breakfast cereals. J Food Distrib Res. 1994;25(1):82-92. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coster, JM. Trends in generic drug reimbursement in Medicaid and Medicare. US Pharm. 2010:35(6 Generic Drug Review Suppl):14-19. Available at: https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/trends-in-generic-drug-reimbursement-in-medicaid-and-medicare. Accessed February 10, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrank WH, Choudhry NK, Agnew-Blais J, et al. State generic substitution laws can lower drug outlays under Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(7):1383-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shrank WH, Cox ER, Fischer MA, Mehta J, Choudhry NK.. Patients’ perceptions of generic medications: although most Americans appreciate the cost-saving value of generics, few are eager to use generics themselves. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(2):546-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Iosifescu A, Halm EA, McGinn T, Siu AL, Federman AD.. Beliefs about generic drugs among elderly adults in hospital-based primary care practices. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):377-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Colgan S, Faasse K, Martin LR, Stephens MH, Grey A, Petrie KJ.. Perceptions of generic medication in the general population, doctors and pharmacists: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sewell K, Andreae S, Luke E, Safford MM.. Perceptions of and barriers to use of generic medications in a rural African American population, Alabama, 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iosifescu A, Halm EA, McGinn T, Siu AL, Federman AD.. Beliefs about generic drugs among elderly adults in hospital-based primary care practices. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73(2):377-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. What you want to know about generic drugs. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/resources-foryou/consumers/buyingusingmedicinesafely/genericdrugs/ucm574961.pdf. Accessed February 10, 2018.

- 53.Colgan S, Faasse K, Martin LR, Stephens MH, Grey A, Petrie KJ.. Perceptions of generic medication in the general population, doctors and pharmacists: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12):e008915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Unnanuntana A, Jarusriwanna A, Songcharoen P.. Randomized clinical trial comparing efficacy and safety of brand versus generic alendronate (Bonmax®) for osteoporosis treatment. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Loch A, Bewersdorf JP, Kofink D, Ismail D, Abidin IZ, Veriah RS.. Generic atorvastatin is as effective as the brand-name drug (LIPITOR®) in lowering cholesterol levels: a cross-sectional retrospective cohort study. BMC Res Notes. 2017;10(1):291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Babar ZU, Stewart J, Reddy S, et al. An evaluation of consumers’ knowledge, perceptions and attitudes regarding generic medicines in Auckland. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32(4):440-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Figueiras MJ, Cortes MA, Marcelino D, Weinman J.. Lay views about medicines: the influence of the illness label for the use of generic versus brand. Psychol Health. 2010;25(9):1121-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shrank WH, Liberman JN, Fischer MA, Girdish C, Brennan TA, Choudhry NK.. Physician perceptions about generic drugs. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(1):31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF, Goeman JJ.. Small studies are more heterogeneous than large ones: a meta-meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):860-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.de Vos J, Houtzager L, Katsaragaki G, van de Berg E, Cuijpers P, Dekker J.. Meta analysis on the efficacy of pharmacotherapy versus placebo on anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord. 2014;2(1):27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cristea IA, Kok RN, Cuijpers P.. The effectiveness of cognitive bias modification interventions for substance addictions: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hassali MA, Wong ZY, Alrasheedy AA, Saleem F, Mohamad Yahaya AH, Aljadhey H.. Does educational intervention improve doctors’ knowledge and perceptions of generic medicines and their generic prescribing rate? A study from Malaysia. SAGE Open Med. 2014;2:2050312114555722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]