Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) released a new blood cholesterol treatment guideline in November 2013. It is unknown how the new recommendations have affected cholesterol medication use and adherence in a commercial health plan.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate the effect of the 2013 guideline release on antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns and statin adherence in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) compared with a historical control group.

METHODS:

This study was a historical cohort analysis of adult patients (aged 21-75 years) with clinical ASCVD enrolled in a SelectHealth commercial health plan. Patients were included in the guideline implementation cohort if they had a medical claim with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis of ASCVD in the year before the November 2013 ACC/AHA guideline release. The index date was defined as the first outpatient medical claim with an ICD-9-CM for ASCVD in the first 6 months after the guideline was released. Patients were required to have continuous enrollment for ≥ 1 year before and after the index date. These same criteria were applied to patients exactly 4 years earlier to identify a historical control group. Patients meeting these criteria formed the antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns cohort. Of these, patients who also had ≥1 pharmacy claim for a statin in the 1-year pre- and post-index periods were included in the statin adherence cohort. Antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns were assessed using pharmacy claims for antihyperlipidemic medications in the 1-year pre- and post-index periods. Antihyperlipidemic medication claims were classified as a nonstatin cholesterol medication, low-intensity statin, moderate-intensity statin, or high-intensity statin. To address differences in pre-index antihyperlipidemic medications between the guideline implementation and historical control groups, patients were randomly matched 1:1 based on pre-index classification in a post hoc analysis. Post-index antihyperlipidemic classifications were compared between groups using a Stuart-Maxwell test. The change in mean statin adherence (proportion of days covered [PDC]) was compared within and between groups using paired and independent t-tests, respectively. The proportion of adherent patients (PDC ≥ 0.80) in the pre- and post-index periods was compared between groups using a chi-square test. A multivariable logistic regression was used to compare the likelihood of being adherent in the post-index period while controlling for pre-index adherence and other potential confounders.

RESULTS:

A total of 7,818 adult members with ASCVD in the index period and 1 year before the index period were identified. Of those, 1,841 patients met the criteria to be included in the analysis, and 1,526 patients were matched on antihyperlipidemic classification and included in the antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns analysis. Baseline characteristics were similar, although the guideline implementation group was younger (58.3 vs. 60.5 years, P < 0.001), and more were male (74.8% vs. 71.3%, P = 0.106) than the historical control group. In the matched cohort, there was a significant difference in the post-index antihyperlipidemic classification (P < 0.001), which appeared to be a result of the difference in nonstatin cholesterol medications (guideline 6.9% vs. historical 13.0%) and high-intensity statins (guideline 23.7% vs. historical 16.3%). Of the 1,841 patients in the antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns cohort, 919 patients met inclusion criteria for the statin adherence analysis. Although PDC decreased over time in both groups, significantly more patients in the guideline implementation group were adherent in the post-index period than the historical control group (66.5% vs. 57.3%, respectively; P = 0.005). Additionally, patients in the guideline implementation group were more likely than the historical control to be adherent in the post-index period when adjusting for potential confounders (OR = 1.49, 95% CI = 1.10-2.03; P = 0.011).

CONCLUSIONS:

Since the release of the updated ACC/AHA treatment guideline, more commercial health plan patients with ASCVD used high-intensity statins and fewer used nonstatin cholesterol medications than historical controls. Additionally, since the guideline release, more patients are adherent to statin therapy than historical controls. This study provides managed care organizations with valuable information regarding the effect of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline.

What is already known about this subject

The updated 2013 American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) blood cholesterol treatment guideline represents a major shift in treating atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

The 2013 guideline recommendations were projected to increase the number of persons using statin therapy, but real-world observations of how treatment use has changed has been limited.

Adherence to statin medications has been shown to be relatively low, and the effect of removing the treat to target cholesterol goals has not been studied.

What this study adds

This study compared, among patients with ASCVD, the effect of the ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline on antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns and adherence to a historical control group.

More patients with ASCVD received high-intensity statins and fewer received nonstatin cholesterol medications after the guideline release than historical controls.

A greater proportion of patients with ASCVD were adherent to statin therapy after the guideline release than historical controls.

In November 2013, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) released the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults, which updated lipid treatment and replaced the long-standing method of treating to blood cholesterol targets established by the Adult Treatment Panel III (ATP III) guideline.1,2 Rather than recommending specific low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) goals, the guideline endorses treatment with certain “statin intensities” based on patient characteristics and risk factors.1 The new guideline identifies 4 major statin benefit groups, 1 of which is patients with clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) taking statins for secondary prevention. For patients aged > 75 years with clinical ASCVD, a moderate-intensity statin is recommended; for adults aged ≤ 75 years with clinical ASCVD, a high-intensity statin is recommended.1

Because of the 2013 guideline recommendations, a projected 12.8 million additional U.S. adults may be eligible for statin therapy. While the majority of this increase will likely occur among adults using statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events,3 the number of patients eligible for statin therapy as secondary prevention may also increase. However, because of the similar eligibility criteria outlined in the ATP III guideline, this increase will not likely be as drastic.2,3 While observational studies are beginning to examine changes to antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns after the release of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline, they have thus far been limited to a single health system with a relatively small sample size.4 The impact of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on broader populations remains unknown.

The 2013 ACC/AHA guideline emphasizes adherence to lifestyle modifications and statins as essential components of primary and secondary prevention of ASCVD.1 Adherence to statin therapies is critical to reducing the risk of cardiovascular events, and statin nonadherence is a major challenge to optimal management.5-7 A meta-analysis of 20 studies revealed that adherence to statins is poor; only 57% of patients using statins for primary prevention and 76% using them for secondary prevention are considered adherent.8 Furthermore, adherence to statins decreases over time, with as few as 26% of patients considered adherent after 5 years.9 Nonadherent patients receive little or no benefit in reduction of cardiovascular events or mortality.4,10-13 By eliminating the emphasis of LDL-C treatment targets during follow-up, the treatment process may be simplified, but removing LDL-C targets may also affect positive reinforcement of patient adherence behaviors. Overall, the effect that the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline may have had on statin adherence remains unknown.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline release on antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns and statin adherence in adult members of a regional managed care organization using a historical control group.

Methods

Patients and Data Source

This study was a historical cohort analysis of adult patients with clinical ASCVD enrolled in a SelectHealth commercial health plan. SelectHealth is a nonprofit regional managed care organization that covers approximately 800,000 lives from the Intermountain region, with commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid plans available. Additionally, SelectHealth is part of an integrated health system with Intermountain Healthcare, which is a nonprofit health system with 22 hospitals and over 185 clinics across Utah and Idaho. Data for the study were collected from SelectHealth pharmacy and medical claims. The Intermountain Healthcare Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Commercially insured patients were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 21 years, which corresponds to the age recommendations in the 2013 ACC/AHA cholesterol guideline.1 Patients were also required to have a medical claim with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis of ASCVD (Appendix A, available in online article) in the year before the guideline release in the guideline implementation group (i.e., November 12, 2012-November 12, 2013) and over a similar time frame but 4 years before in the historical control group (i.e., November 12, 2008-November 12, 2009). The historical control group was chosen as 4 years before the guideline group, since most patients are enrolled in a health plan for 2-3 years, and a relatively recent comparator would minimize some differences in generic availability of antihyperlipidemic treatments. Because antihyperlipidemic treatment may change for a variety of reasons and drug adherence may change over time, including a comparator group was an important component of this analysis and was used as an effort to isolate the effect of the guideline release. For the guideline implementation group, the index period was November 12, 2013-May 12, 2014, which was the 6-month period following the guideline release, and for the historical control group, the index period was November 12, 2009-May 12, 2010. The index date was defined as the date of the first cardiovascular- or lipid-related outpatient medical claim during the index period (Appendix A contains a list of ICD-9-CM codes used; ICD-9-CM codes could be in any position). This date was chosen because it represented an opportunity for the provider and patient to discuss and change antihyperlipidemic medications. To ensure that all patients would have the same recommended treatment according to the guideline, patients were also required to be aged ≤ 75 years on the index date. Additionally, patients were required to have ≥ 365 days of continuous enrollment in the pre- and post-index periods. Patients meeting these criteria comprised the antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns cohort.

To examine statin adherence, in addition to the previously listed criteria, patients had to have ≥1 pharmacy claim for a statin between -395 days pre-index date and index date as well as ≥1 pharmacy claim for a statin between index date and +365 days post-index date. Finally, to ensure that patients had similar possible exposures to statins in the pre- and post-index periods, patients were required to have ≥1 pharmacy claim for a statin within ±90 days of start of pre-index period (-365 days ±90 days). Patients meeting all of these criteria comprised the statin adherence cohort.

Antihyperlipidemic Treatment Patterns

Prescription claims for antihyperlipidemic medications were identified using Generic Product Identifier codes in the 1-year pre- and post-index periods. During the pre- and post-index periods, each claim for an antihyperlipidemic medication was classified as a nonstatin cholesterol medication, low-intensity statin, moderate-intensity statin, or high-intensity statin according to the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline definition.1 If patients did not have any prescription claims for an antihyperlipidemic medication, they were classified as having none. Patients were then assigned a classification in the pre- and post-index years according to the highest intensity statin received during the period. If patients received a nonstatin cholesterol medication and a statin, they were classified according to the statin intensity received.

Statin Adherence

Statin adherence in the pre- and post-index periods was calculated using the proportion of days covered (PDC). PDC was calculated by dividing the number of days supplied by 365 days, taking into account early refills by shifting the start date of the prescription filled early to the end of the days supply of the previous prescription fill and only considering the 365 days during the 1-year pre- and post-index periods. Statin adherence was estimated at the class level, which allowed patients to switch between statins. Fill dates were adjusted if switches were filled early. Additionally, prescription claims from before the start of the pre-index period with a days supply that carried over into the pre-index period were included. If this occurred, only the days actually within the 365-day pre-index period were included in calculating PDC (e.g., a prescription claim with a 30-day supply filled 15 days before the start of the pre-index period resulted in 15 days of coverage in the pre-index period). Pharmacy claims from the pre-index period with a days supply that carried over into the post-index period were handled similarly. Patients were considered adherent if they had a PDC ≥ 0.80 and nonadherent if the PDC was < 0.80.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were identified in the 1-year pre-index period and included demographics (i.e., age and sex) and clinical characteristics (i.e., comorbidities identified by ICD-9-CM code included hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, overweight, obesity, anxiety, depression, bipolar, and psychotic disorders [Appendix A]) as well as average antihyperlipidemic or statin copay. Based on the authors’ clinical judgment, comorbidities associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events or that may affect medication adherence were selected. Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations (SD) and compared between groups using independent t-tests. Categorical variables were reported using frequencies and percentages and were compared between groups using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. The baseline characteristics of the antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns cohort were described, as well as the subset of patients meeting the criteria of the statin adherence cohort.

Antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns were described using frequencies and percentages and were compared using chi-square tests. However, given the significant differences in antihyperlipidemic classification identified between the groups in the pre-index period, a post hoc analysis was used to better understand and describe changes in treatment patterns. In the post hoc analysis, the post-index antihyperlipidemic classifications were compared between groups after patients in the guideline implementation group were randomly matched 1:1 to patients in the historical control group on pre-index antihyperlipidemic classification. Patients who did not match on pre-index antihyperlipidemic class were excluded from the post hoc analysis. In the post hoc analysis, baseline characteristics were compared between the groups using paired t-tests and McNemar’s test or Stuart-Maxwell test, as appropriate, and antihyperlipidemic treatments in the post-index period were compared using the Stuart-Maxwell test.

For the statin adherence cohort, the change in mean statin adherence from the pre- to the post-index periods was compared within the guideline implementation and historical control groups using paired t-tests and between groups using an independent t-test. The proportion of patients considered adherent in the pre- and post-index periods was compared between the guideline implementation and historical control groups using a chi-square test. A multivariable logistic regression was then used to compare the likelihood of being adherent in the post-index period between the guideline implementation and historical control cohorts, while controlling for baseline adherence classification and other potential confounders (i.e., the baseline characteristics previously described). A backward stepwise approach was used in covariate selection for the multivariable logistic regression using a P value of > 0.2 as a threshold.14 Covariates considered clinically meaningful were included regardless of the P value obtained in the stepwise selection process. The final covariates included in the model were age, sex, statin adherence in the pre-index period, mean statin copay in pre-index period, hypertension, anxiety, and depression. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

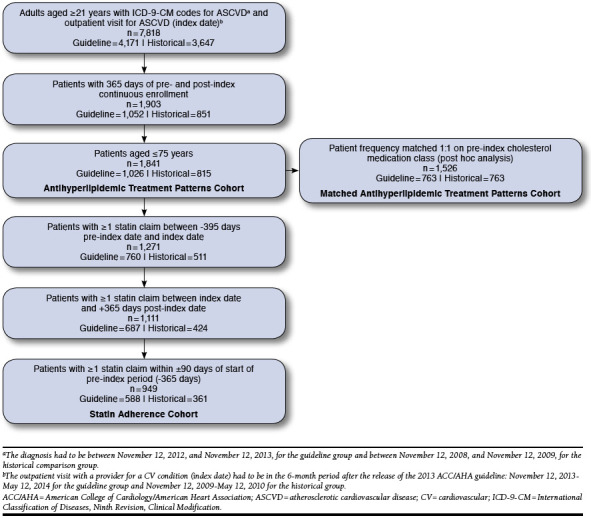

A total of 7,818 adult patients were identified with an outpatient medical claim for ASCVD in the 6-month index period period, as well as a claim with a diagnosis of ASCVD in the 1 year before (Figure 1). Of those, 1,841 patients met the criteria to be included in the antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns cohort, and 1,526 patients were matched 1:1 on pre-index antihyperlipidemic classification. Of the 1,841 patients in the antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns cohort, 949 patients met all inclusion criteria for the statin adherence cohort.

FIGURE 1.

Patient Identification Flowchart

Antihyperlipidemic Treatment Patterns

A total of 1,026 patients in the guideline implementation and 815 in the historical control groups were included in the antihyperlipidemic treatment cohort (Table 1). The guideline implementation group was younger (mean [SD] for age: guideline 58.3 [7.4] vs. historical 60.5 [8.6], P < 0.001), had a higher proportion with a diagnosis for obesity (guideline 14.1% vs. historical 10.2%, P = 0.013), and had a lower proportion with a diagnosis for bipolar disorder (guideline 0.1% vs. historical 0.9%, P = 0.025). Among those patients with ≥1 antihyperlipidemic fill, patients in the guideline implementation group had a lower mean antihyperlipidemic copay (guideline $20 vs. historical $24, P < 0.001) and fewer mean antihyperlipidemic fills (guideline 7.3 [4.9] vs. historical 8.4 [6.1], P < 0.001). The characteristics for the matched groups in the post hoc analysis were similar to those before matching on pre-index antihyperlipidemic class, although the difference in bipolar diagnosis was no longer significant (P = 0.077; Appendix B, available in online article).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients in Antihyperlipidemic Treatment Patterns Cohort (N = 1,841)

| Overall (N = 1,841) | Guideline (n = 1,026) | Historical (n = 815) | P Valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, mean [SD] | 59.3 | [8.0] | 58.3 | [7.4] | 60.5 | [8.6] | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1,348 | 73.2 | 767 | 74.8 | 581 | 71.3 | 0.106 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 1,519 | 82.5 | 862 | 84.0 | 657 | 80.6 | 0.065 |

| Hypertension | 1,366 | 74.2 | 765 | 74.6 | 601 | 73.7 | 0.730 |

| Diabetes | 315 | 17.1 | 172 | 16.8 | 143 | 17.5 | 0.704 |

| Overweight | 16 | 0.9 | 10 | 1.0 | 6 | 0.7 | 0.624 |

| Obesity | 228 | 12.4 | 145 | 14.1 | 83 | 10.2 | 0.013 |

| Anxiety | 22 | 1.2 | 11 | 1.1 | 11 | 1.3 | 0.668 |

| Depression | 49 | 2.7 | 26 | 2.5 | 23 | 2.8 | 0.814 |

| Bipolar | 8 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 7 | 0.9 | 0.025 |

| Psychotic disorder | 3 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 1.000 |

| Pre-index antihyperlipidemic medication use | |||||||

| Antihyperlipidemic medication classes | |||||||

| None | 388 | 21.1 | 203 | 19.8 | 185 | 22.7 | < 0.001 |

| Nonstatin medication | 212 | 11.5 | 80 | 7.8 | 132 | 16.2 | |

| Low-intensity statin | 25 | 1.4 | 15 | 1.5 | 10 | 1.2 | |

| Moderate-intensity statin | 742 | 40.3 | 378 | 36.8 | 364 | 44.7 | |

| High-intensity statin | 474 | 25.7 | 350 | 34.1 | 124 | 15.2 | |

| Antihyperlipidemic copay, mean [SD]b | $22 | [$27] | $20 | [$27] | $24 | [$25] | < 0.001 |

| Number of antihyperlipidemic fills, mean [SD]b | 7.8 | [5.5] | 7.3 | [4.9] | 8.4 | [6.1] | < 0.001 |

a Continuous variables compared between guideline and historical groups using t-tests, categorical variables compared using chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

b Among patients with at least 1 antihyperlipidemic fill.

SD = standard deviation.

In the overall treatment patterns cohort before matching, the pre-index medication use classifications were as follows: 21.1% no cholesterol medication, 11.5% nonstatin cholesterol medication, 1.4% low-intensity statin, 40.3% moderate-intensity statin, and 25.7% high-intensity statin. Before matching, there was a significant difference in the pre-index antihyperlipidemic classification between the guideline implementation and historical control groups (P < 0.001; Table 1). This difference was because of the nonstatin cholesterol medications (guideline 7.8% vs. historical 16.2%), moderate-intensity statins (guideline 36.8% vs. historical 44.7%), and high-intensity statins (guideline 34.1% vs. historical 15.2%). After matching on pre-index antihyperlipidemic class, there were no differences in pre-index antihyperlipidemic classifications (both groups: none 24.2%, nonstatin cholesterol medication 10.5%, low-intensity statin 1.3%, moderate-intensity statin 47.7%, and high-intensity statin 16.3%; Appendix B). In the matched post hoc cohort, there was a significant difference in the post-index antihyperlipidemic classification between the guideline implementation and historical control groups (P < 0.001; Table 2). This difference appeared to be a result of a lower use of nonstatin cholesterol medications (guideline 6.9% vs. historical 13.0%) and an increased use of high-intensity statins (guideline 23.7% vs. historical 16.3%) in the guideline implementation group.

TABLE 2.

Post-index Antihyperlipidemic Medication Classification in the Subgroup of the Antihyperlipidemic Treatment Patterns Cohort Matched on Pre-index Classification in a Post Hoc Analysis (N = 1,526)

| Overall (N = 1,526) | Guideline (n = 763) | Historical (n = 763) | P Valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Antihyperlipidemic medication classification | |||||||

| None | 386 | 25.3 | 193 | 25.3 | 193 | 25.3 | < 0.001 |

| Nonstatin medication | 152 | 10.0 | 53 | 6.9 | 99 | 13.0 | |

| Low-intensity statin | 24 | 1.6 | 14 | 1.8 | 10 | 1.3 | |

| Moderate-intensity statin | 659 | 43.2 | 322 | 42.2 | 337 | 44.2 | |

| High-intensity statin | 305 | 20.0 | 181 | 23.7 | 124 | 16.3 | |

a Post-index medication classifications compared for matched pairs using Stuart-Maxwell test.

Statin Adherence

A total of 588 patients in the guideline implementation and 361 in the historical control groups met all the inclusion criteria to be included in the analysis (Table 3). The guideline implementation group was significantly younger than the historical control group (mean [SD]) for age: guideline 58.4 [6.9] vs. historical 62.2 [6.6], P < 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant difference in the statin intensity classification in the pre-index period between the groups (P < 0.001; Table 3). There were fewer moderate-intensity (guideline 50.3% vs. historical 71.2%) and more high-intensity statin users in the guideline implementation group (guideline 47.8% vs. historical 27.1%). The guideline implementation group also had a lower mean [SD] statin copay (guideline $18 [$25] vs. historical $23 [$26], P < 0.001).

TABLE 3.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients in Statin Adherence Cohort (N = 949)

| Overall (N = 949) | Guideline (n = 588) | Historical (n = 361) | P Valuea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, mean [SD] | 59.8 | [7.0] | 58.4 | [6.9] | 62.2 | [6.6] | < 0.001 |

| Male | 742 | 78.2 | 467 | 79.4 | 275 | 76.2 | 0.274 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 851 | 89.7 | 534 | 90.8 | 317 | 87.8 | 0.172 |

| Hypertension | 727 | 76.6 | 454 | 77.2 | 273 | 75.6 | 0.630 |

| Diabetes | 186 | 19.6 | 120 | 20.4 | 66 | 18.3 | 0.474 |

| Overweight | 8 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.8 | 1.000 |

| Obesity | 118 | 12.4 | 76 | 12.9 | 42 | 11.6 | 0.613 |

| Anxiety | 8 | 0.8 | 3 | 0.5 | 5 | 1.4 | 0.165 |

| Depression | 26 | 2.7 | 17 | 2.9 | 9 | 2.5 | 0.873 |

| Bipolar | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 1.000 |

| Psychotic disorder | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.3 | 1.000 |

| Pre-index statin intensity | |||||||

| Low-intensity statin | 17 | 1.8 | 11 | 1.9 | 6 | 1.7 | < 0.001 |

| Moderate-intensity statin | 553 | 58.3 | 296 | 50.3 | 257 | 71.2 | |

| High-intensity statin | 379 | 39.9 | 281 | 47.8 | 98 | 27.1 | |

| Pre-index statin copay, mean [SD] | $20.02 | [$25.19] | $17.80 | [$24.51] | $23.25 | [$25.81] | < 0.001 |

a Continuous variables compared between guideline and historical groups using t-tests, categorical variables compared using chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate.

SD = standard deviation.

In the overall statin adherence cohort, the mean [SD] PDC in the pre-index period was 0.82 [0.22]; mean PDC was 0.83 [0.20] in the guideline implementation and 0.80 [0.23] in the historical control groups. Adherence decreased from the pre- to the post-index periods for each group. The mean ([SD], P value for change) in the post-index period was 0.79 (0.25, P < 0.001) for the overall group, 0.81 (0.24, P = 0.040) for the guideline implementation group, and 0.75 (0.27, P < 0.001) for the historical control group. The proportion of patients with a PDC ≥ 0.80 in the pre-index period was not significantly different between the groups (guideline 69.9% vs. historical 65.7%, P = 0.172; Table 4). However, significantly more patients in the guideline group were considered adherent in the post-index period (guideline 66.5% vs. historical 57.3%, P = 0.005). When controlling for potential confounders, patients in the guideline implementation group were significantly more likely than the historical control group (odds ratio [OR] = 1.49, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.10-2.03, P = 0.011) to be adherent in the post-index period (Table 5). However, being considered adherent in the pre-index period was the strongest predictor of being adherent in the post-index period (OR = 5.65, 95% CI = 4.18-7.68, P < 0.001).

TABLE 4.

Statin Adherence in the Pre- and Post-index Periods in Statin Adherence Cohort (N = 949)

| Overall (N = 949) | Guideline (n = 588) | Historical (n = 361) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-index period | ||||

| Statin PDC, mean [SD] | 0.82 [0.22] | 0.83 [0.20] | 0.80 [0.23] | 0.018 |

| Nonadherent,b n (%) | 301 (31.7) | 177 (30.1) | 124 (34.3) | 0.172 |

| Adherent,b n (%) | 648 (68.3) | 411 (69.9) | 237 (65.7) | |

| Post-index period | ||||

| Statin PDC, mean [SD] | 0.79 [0.25] | 0.81 [0.24] | 0.75 [0.27] | < 0.001 |

| Nonadherent,b n (%) | 351 (37.0) | 197 (33.5) | 154 (42.7) | 0.005 |

| Adherent,b n (%) | 598 (63.0) | 391 (66.5) | 207 (57.3) | |

a Guideline and historical groups were compared using chi-square test.

b Nonadherent was defined as PDC < 0.80, and adherent was defined as PDC ≥ 0.80.

PDC = proportion of days covered; SD = standard deviation.

TABLE 5.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Model Predicting Likelihood of Being Adherent Versus Nonadherent in the Post-index Period in Statin Adherence Cohort (N = 949)

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

| Guideline implementation group vs. historical control group | 1.49 | 1.10-2.03 | 0.011 |

| Adherent vs. nonadherent in pre-index perioda | 5.65 | 4.18-7.68 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99-1.04 | 0.228 |

| Male vs. female | 1.31 | 0.93-1.85 | 0.126 |

| Mean statin copay in pre-index period | 1.00 | 0.99-1.00 | 0.204 |

| Hypertension | 1.43 | 1.02-2.00 | 0.037 |

| Anxiety | 2.81 | 0.61-15.01 | 0.191 |

| Depression | 0.35 | 0.14-0.82 | 0.016 |

a Adherent was defined as PDC ≥ 0.80.

CI = confidence interval; PDC = proportion of days covered.

Discussion

This study examined the effect of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns and statin adherence in patients with clinical ASCVD in a regional managed care organization. When compared with a historical control group on similar antihyperlipidemic medication classes, patients in the guideline implementation group were more likely to receive high-intensity statins and less likely to receive nonstatin cholesterol-lowering medications in the post-index period. However, according to the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline, the entire antihyperlipidemic treatment patterns cohort should have been taking high-intensity statins. After the release of the guideline, only 37.2% of the unmatched and 23.7% of the matched guideline implementation group were on high-intensity statins. Additionally, 22.1% of the unmatched and 25.3% of the matched guideline implementation group were untreated. This indicates that, while treatment patterns have shifted since the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline release, treatment inertia may exist, and there is room for improvement. While the entire population of patients should have been on statins according to the ACC/AHA guidelines, some patients may have experienced statin intolerance. In real-world settings, statin intolerance has been estimated to occur in 10%-15% of patients treated with statins, so it is likely not all of the untreated patients had statin intolerance.15,16 Additionally, patients in the guideline implementation group were more likely than historical controls to be adherent in the post-index period. These results may indicate that, at least initially, the release of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline affected patient adherence. However, only 67% of the guideline implementation group had a PDC ≥ 0.80 in the post-index period, and efforts may have been made to further promote statin adherence.

Although the release of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline was expected to broadly affect antihyperlipidemic medication use, before this study, the actual effect on treatment patterns and statin adherence was unknown. Because the implementation of new guidelines can take an extensive amount of time, it is important for managed care organizations to assess how patients and providers adapt to new guidelines. These assessments provide opportunities for managed care to encourage good clinical practice among providers and meet quality metrics that change to meet new standards. This study provides managed care organizations with valuable information regarding the effect of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline and highlights the need for managed care organizations and health systems to consider implementing care process models, provider education, or other interventions to help improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines.

The antihyperlipidemic treatment pattern analysis results are similar in direction to a previously published study that examined prescribing patterns in patients with ASCVD seen in primary care clinics in a university health system.4 That study found that high-intensity statin use in patients aged between 18 and 75 years had increased from 26% to 45% (P = 0.01). While the magnitude of effect seen was greater than in the current study, there were several key differences. First, the previous study only included patients seen in primary care clinics from a single university health system and had a relatively small sample size. These parameters may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the previous study used medical records and examined statins prescribed, not necessarily filled. Further, it only examined statin prescription orders for patients during 1 period of time, either before or after the release of the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline. Patients with orders in both periods were randomly assigned to one of the periods. Thus, it did not necessarily consider changes to therapy for patients. The current study overcomes some of these limitations by using claims data from a regional managed care organization, including a historical cohort for comparison, and looking specifically at changes to antihyperlipidemic therapy.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study are worthy of discussion. First, the index date was assumed to be a point at which the provider and patient had the opportunity to discuss adjusting cholesterol medications and address statin adherence. This was a surrogate marker for the provider’s implementation of the new cholesterol guidelines. This surrogate does not identify actual uptake of the guideline in clinical practice, and future research should consider examining this. Historically, guideline adoption has been slow, but information dissemination has changed significantly, and it is unknown how quickly guidelines are adopted. Also, since only claims data were used for this analysis, patients who were not candidates for statin therapy, for reasons such as previous intolerance or ineffectiveness, could not be identified. Future studies may consider using claims and medical record data to overcome this.

Second, the current study only considered patients with ASCVD and did not examine other groups to which statins offer benefits identified in the guideline. Similarly, SelectHealth launched Medicare and managed Medicaid plans in 2013, so these populations were not included in the analysis because of the lack of available data during the study period. Along these lines, Medicare star ratings include a statin adherence measure, and it is unknown how this might have impacted the focus on statin adherence in the overall health plan. While this analysis did not include Medicare patients, the addition of a Medicare plan between the historical group and guideline cohorts may have provided an incidental focus on statin adherence. Future studies should include the effect of the ACC/AHA guideline on Medicare and Medicaid populations.

Finally, patients were only required to have a single ASCVD diagnosis in the pre-index period. Some patients in the antihyperlipidemic treatment cohort may have thus been relatively newly diagnosed and not yet started treatment. Also, by requiring at least 1 claim for a statin in the pre- and post-index periods for the statin adherence cohort, included patients had received statin therapy for some time. This may limit the generalizability of the results of the adherence analysis.

Conclusions

Since the release of the updated ACC/AHA treatment guideline, more patients with ASCVD are using high-intensity statins, and fewer are using nonstatin cholesterol medications than historical controls. The significant difference between the types of antihyperlipidemic medication use could be a result of prescribing based on the guideline and/or practicing of evidence-based medicine. Additionally, since the guideline release, more patients were adherent to statin therapy than historical controls. The difference in statin adherence could be a result of provider emphasis on adherence, as recommended by the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline, but previous statin adherence was still the largest predictor of adherence. However, the effect of a possible emphasis on improving statin adherence was not studied and should be examined in future studies.

APPENDIX A. List of ICD-9-CM Codes Used

| Condition | Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease | ||

| Heart disease | 410.** | Acute myocardial infarction |

| 411.** | Other acute and subacute forms of ischemic heart disease | |

| 412 | Old myocardial infarction | |

| 413.* | Angina pectoris | |

| 414.** | Other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease | |

| 429.2 | Cardiovascular disease, unspecified | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 437.1 | Other generalized ischemic cerebrovascular disease |

| Atherosclerosis | 440.** | Atherosclerosis |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 443.** | Other peripheral vascular disease |

| Congenital heart anomaly | 746.85 | Coronary artery anomaly |

| Complications after cardiac procedures | 996.03 | Mechanical complication due to coronary bypass graft |

| Post-procedural status | V45.81 | Aortocoronary bypass status |

| Aortic aneurysm | 441.** | Aortic aneurysm and dissection |

| Cardiovascular- or lipid-related outpatient visits | ||

| Heart disease | 410.** | Acute myocardial infarction |

| 411.** | Other acute and subacute forms of ischemic heart disease | |

| 412 | Old myocardial infarction | |

| 413.* | Angina pectoris | |

| 414.** | Other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease | |

| 415.** | Acute pulmonary heart disease | |

| 416.* | Chronic pulmonary heart disease | |

| 417.* | Other diseases of pulmonary circulation | |

| 427.** | Cardiac dysrhythmias | |

| 428.** | Heart failure | |

| 429.** | Ill-defined descriptions and complications of heart disease | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 430 | Subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| 431 | Intracerebral hemorrhage | |

| 432* | Other and unspecified intracranial hemorrhage | |

| 433.* | Occlusion and stenosis of precerebral arteries | |

| 434.* | Occlusion of cerebral arteries | |

| 435.* | Transient cerebral ischemia | |

| 436 | Acute, but ill-defined, cerebrovascular disease | |

| 437.* | Other and ill-defined cerebrovascular disease | |

| 438.** | Late effects of cerebrovascular disease | |

| Atherosclerosis | 440.** | Atherosclerosis |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 443.** | Other peripheral vascular disease |

| Congenital heart anomaly | 746.85 | Coronary artery anomaly |

| Complications after cardiac procedures | 996.0* | Mechanical complication of cardiac device implant and graft |

| 996.1 | Mechanical complication of other vascular device, implant, and graft | |

| 996.61 | Infection and inflammatory reaction due to cardiac device, implant, and graft | |

| 996.71 | Other complications due to heart valve prosthesis | |

| 996.72 | Other complications due to other cardiac device, implant, and graft | |

| 996.74 | Other complications due to other vascular device, implant, and graft | |

| Postprocedural status | V45.0* | Cardiac device in situ |

| V45.81 | Aortocoronary bypass status | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 272.* | Disorders of lipoid metabolism |

| Aortic aneurysm | 441.** | Aortic aneurysm and dissection |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Anxiety | 300.0* | Anxiety states |

| Depression | 296.2* | Major depressive disorder, single occurrence |

| 296.3* | Major depressive disorder, recurring | |

| 311 | Depressive disorder not otherwise specified | |

| Bipolar disorder | 296.0* | Bipolar I disorder, single manic episode |

| 296.4* | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode (or current) manic | |

| 296.5* | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode (or current) depressed | |

| 296.6* | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode (or current) mixed | |

| 296.7* | Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode (or current) unspecified | |

| 296.80 | Bipolar disorder, unspecified | |

| 296.89 | Other bipolar disorders | |

| Psychotic disorders | 295.** | Schizophrenia disorders |

| 297.** | Delusional disorders | |

| 298.** | Other non-organic psychoses | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 272.* | Disorders of lipoid metabolism |

| Hypertension | 401.* | Essential hypertension |

| 402.** | Hypertensive heart disease | |

| 403.** | Hypertensive chronic kidney disease | |

| 404.** | Hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease | |

| 405.** | Secondary hypertension | |

| Diabetes | 250.** | Diabetes mellitus |

| Overweight | 278.02 | Overweight |

| Obesity | 278.00 | Obesity, unspecified |

| 278.01 | Morbid obesity | |

ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

APPENDIX B. Baseline Characteristics of Patients in the Antihyperlipidemic Medication Treatment Patterns Cohort After Post Hoc Matching on Pre-index Antihyperlipidemic Class

| Overall (N = 1,526) | Guideline (n = 763) | Historical (n = 763) | P Valuea | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Demographics | |||||||

| Age, mean [SD] | 59.5 | [8.1] | 60.5 | [8.6] | 58.6 | [7.5] | < 0.001 |

| Male | 1,110 | 72.7 | 543 | 71.2 | 567 | 74.3 | 0.187 |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||||

| Hyperlipidemia | 1,232 | 80.7 | 610 | 79.9 | 622 | 81.5 | 0.454 |

| Hypertension | 1,124 | 73.7 | 560 | 73.4 | 564 | 73.9 | 0.860 |

| Diabetes | 260 | 17.0 | 130 | 17.0 | 130 | 17.0 | 1.000 |

| Overweight | 13 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.7 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.579 |

| Obesity | 196 | 12.8 | 77 | 10.1 | 119 | 15.6 | 0.002 |

| Anxiety | 19 | 1.2 | 11 | 1.4 | 8 | 1.0 | 0.646 |

| Depression | 42 | 2.8 | 22 | 2.9 | 20 | 2.6 | 0.877 |

| Bipolar | 8 | 0.5 | 7 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.077 |

| Psychotic disorder | 3 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.3 | 1.000 |

| Pre-index antihyperlipidemic medication use | |||||||

| Antihyperlipidemic medication classes | |||||||

| None | 370 | 24.2 | 185 | 24.2 | 185 | 24.2 | 1.000 |

| Nonstatin medication | 160 | 10.5 | 80 | 10.5 | 80 | 10.5 | |

| Low-intensity statin | 20 | 1.3 | 10 | 1.3 | 10 | 1.3 | |

| Moderate-intensity statin | 728 | 47.7 | 364 | 47.7 | 364 | 47.7 | |

| High-intensity statin | 248 | 16.3 | 124 | 16.3 | 124 | 16.3 | |

| Antihyperlipidemic copay, mean [SD]b | $22 | [$26] | $19 | [$26] | $24 | [$26] | < 0.001 |

| Number of antihyperlipidemic fills, mean [SD]b | 7.6 | [5.3] | 6.6 | [4.3] | 8.5 | [6.1] | < 0.001 |

a Continuous variables compared between guideline and historical groups using paired t-tests, and categorical variables compared using McNemar’s test or Maxwell-Stuart test as appropriate.

b Among patients with at least 1 antihyperlipidemic fill.

SD = standard deviation.

References

- 1.Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) . Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143-421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D’Agostino RB Sr, et al. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1422-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, et al. Full coverage for preventive medications after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(22):2088-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allonen J, Nieminen MS, Lokki M, et al. Mortality rate increases steeply with nonadherence to statin therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(11):E22-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Medication nonadherence is associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2008;155(4):772-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV.. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2002;288(4):462-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchard MH, Dragomir A, Blais L, Berard A, Pilon D, Perreault S.. Impact of adherence to statins on coronary artery disease in primary prevention. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(6):698-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benner JS, Glynn RJ, Mogun H, Neumann PJ, Weinstein MC, Avorn J.. Long-term persistence in use of statin therapy in elderly patients. JAMA. 2002;288(4):455-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Compliance and adverse event withdrawal: their impact on the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Eur Heart J. 1997;18(11):1718-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumbhani DJ, Steg PG, Cannon CP, et al. Adherence to secondary prevention medications and four-year outcomes in outpatients with atherosclerosis. Am J Med. 2013;126(8):693-700.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naderi SH, Bestwick JP, Wald DS.. Adherence to drugs that prevent cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis on 376,162 patients. Am J Med. 2012;125(9):882-87.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perreault S, Dragomir A, Blais L, et al. Impact of better adherence to statin agents in the primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(10):1013-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Budtz-Jørgensen E, Keiding N, Grandjean P, Weihe P.. Confounder selection in environmental epidemiology: assessment of health effects of prenatal mercury exposure. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(1):27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B.. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients: the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19(6):403-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA.. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(3):208-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]