Abstract

BACKGROUND: Several cost analysis studies have been conducted looking at clinical and economic outcomes associated with clinical pharmacist services in a variety of health care settings. However, there is a paucity of data regarding the economic impact of clinical pharmacist involvement in formulary management at the hospital level.

OBJECTIVE: To evaluate economic outcomes of a pharmacist-adjudicated formulary management consult service in a Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center offering outpatient and inpatient services.

METHODS: This VA medical center uses a pharmacist-adjudicated formulary management system for review of restricted drug consults. A retrospective review of electronic medical records was conducted to identify restricted drug consults at this institution between January 1, 2014, and March 31, 2014. Only restricted drug consults that were not approved were included for evaluation in order to best characterize the effects of formulary interventions by pharmacists. Economic outcomes were determined as direct cost savings by comparing the cost of requested drug with the recommended drug and accounting for the cost of pharmacist review. Characteristics of consults that were not approved and pharmacist rationale were also evaluated.

RESULTS: Of 1,802 restricted drug consults adjudicated by a pharmacist during the study period, 198 consults in 190 individual patients met criteria for inclusion and were evaluated. The most commonly requested indications were dyslipidemia, pain, and diabetes, while the most commonly requested drugs were rosuvastatin, insulin pens, tamsulosin, varenicline, ezetimibe, and rivaroxaban. The majority of consults were requested for outpatient use. Total cost savings among 195 evaluable consults was $420,324.05, while mean cost savings per consult was $2,229.43 (range: −$3,009.27-$65,982.36). The highest cost savings were seen with outpatient use.

CONCLUSIONS: A pharmacist-adjudicated formulary consult service in a VA medical center was associated with a substantial cost savings after adjustment for cost of pharmacist review. Future research should assess clinical outcomes associated with a restrictive formulary management system.

DISCLOSURES: No outside funding supported this study. None of the authors report any financial interests or potential conflict of interest with regard to this work.

Study concept and design were created by all authors. Data were collected and interpreted by Britt, with input from all authors. The manuscript was written by Britt and revised by all authors.

What is already known about this subject

Managed care pharmacy and formulary management have become a central focus as an approach to decrease costs associated with health care.

Clinical pharmacy services have been associated with positive economic and clinical outcomes in a variety of health care settings.

There is a paucity of data regarding clinical and economic impact of clinical pharmacist involvement in formulary management at the hospital level.

What this study adds

This study evaluated economic outcomes of a pharmacist-adjudicated formulary management consult service in a Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center offering outpatient and inpatient services.

A pharmacist-adjudicated formulary management consult service in a VA medical center was associated with substantial cost savings after adjusting for the cost of pharmacist review.

Health care in the United States has shifted focus towards value-based services. Accordingly, it is becoming increasingly important for pharmacists to demonstrate their value to the health care system.1 Managed care pharmacy and formulary management are central approaches to decreasing costs associated with health care. A formulary system is a process for establishing and continually reviewing policies and procedures in order to ensure selection of safe, appropriate, and cost-effective drug products and therapies.2-6 Pharmacists are often integrally involved in development and management of an institution’s formulary.2-5

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States. The VA National Formulary (VANF) is maintained by the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Services and guides management of drug therapy at all VA medical centers, promoting a uniform pharmacy benefit nationwide.7,8 The VANF relies heavily on evidence-based drug evaluations in order to pursue VA goals of improved patient safety, appropriate drug use, improved access to drug products and therapies, and reduced drug acquisition costs. The VA operates using a closed formulary, which means that access to some medications is restricted. Management and enforcement of the formulary occurs primarily at the individual medical center level, although VA clinical guidance documents are developed to assist individual medical centers with managing the formulary process, including drug monographs, drug class reviews, criteria for use, and pharmacologic management guidelines.8,9

Several cost analysis studies have been conducted to determine economic outcomes associated with clinical pharmacist services in a variety of health care settings.10-15 However, there is a paucity of data regarding the economic impact of clinical pharmacist involvement in formulary management.16-20 Most available studies evaluate specific interventions, such as formulary conversion,16-19 or focus on a more lenient formulary management approach.19-20 The purpose of this study was to evaluate economic outcomes of a pharmacist-adjudicated formulary management consult service in a VA medical center offering outpatient and inpatient services. The evaluation characterized the restricted drug consults that were not approved and pharmacists’ interventions and rationale and estimated the resultant economic effect of the interventions.

Description of VA Facility

The study was conducted in a 271-bed tertiary care VA medical center, which serves as a referral, teaching, and research facility. The medical center provides general and specialty ambulatory and inpatient services. Several community-based outpatient clinics operate under the medical center to provide greater access to care for veterans in a broader geographical area.

This medical center enforces the VANF through use of electronic restricted drug consults developed from the national VA clinical guidance documents. Medications requiring restricted drug consults include nonformulary drugs, as well as some formulary drugs with specific restrictions or requirements for use. Formulary-restricted drugs are determined by the national PBM or local pharmacy and therapeutics committee based on safety concerns or high cost. To prescribe a restricted drug, providers are required to submit an electronic restricted drug consult, which must be reviewed for appropriateness and safety (adjudicated) before the drug can be filled by the pharmacy; this is analogous to a prior authorization for third-party payers. The review is expected to occur within 96 hours to ensure timely access to medications.

The medical center employs a pharmacist-led formulary management approach for the adjudication of restricted drug consults. Some specialty services without a designated pharmacist use nonpharmacist providers for adjudication of restricted drug consults. A centralized formulary management pharmacist team consisting of 2.5 full-time employee equivalents (FTEE) adjudicates most restricted drug consults. Additionally, decentralized pharmacist teams adjudicate restricted drug consults directly applicable to their areas of specialty clinical practice. The decentralized teams include 3.6 anticoagulation, 2.8 inpatient, and 1 oncology pharmacist FTEEs. The formulary management pharmacists are integrally involved with restricted drug consult adjudication, as well as with consult and policy development, administrative functions, and other responsibilities. The decentralized pharmacists function primarily through direct patient care roles, with consult adjudication being a minor administrative responsibility.

Methods

This study was a single-center retrospective chart review at a tertiary-care VA medical center and was approved by the medical center’s institutional review board. All pharmacist-adjudicated restricted drug consults placed between January and March 2014 were evaluated for eligibility and inclusion in the study. Restricted drug consults were excluded if they were approved, adjudicated by a pharmacy trainee or nonpharmacist provider, or closed administratively. Only nonapproved consults were considered to constitute a pharmacist intervention, since nonapproval resulted in a deviation from what was originally prescribed.

Restricted drug consults meeting criteria for inclusion were analyzed. Additional patient-, consult-, and pharmacy-specific data were obtained by reviewing patients’ electronic medical records. Patient-specific data included age, race, and gender. Consult-specific data included requested drug, duration, indication, and formulary status; requesting provider classification; type of consult (general, anticoagulation, or oncology); and whether the request was for inpatient or outpatient use. Pharmacy-specific data included pharmacy team adjudicating consult, rationale for nonapproval, and recommended alternative therapy. Alternative therapies are recommended based on the clinical judgment of the pharmacist, requirements of the VANF, and the formulary status of potential alternative medications. Rationale for nonapproval was collected to better characterize why consults were not approved; stated rationale was grouped into broad categories determined internally after data collection.

Economic outcomes were assessed through direct cost savings. Medication pricing data were determined using the national VA drug acquisition cost and normalized to cost per day. Individual nonapproved consult direct cost savings were determined for individual consults by subtracting cost of recommended therapy from cost of requested therapy for a set duration and adjusting for cost of consult review. Overall direct cost savings were the sum of individual nonapproved consult direct cost savings but also took into account cost of consult review for all other consults placed during the study time frame (Appendix A, available in online article). Cost of consult review accounted for the pharmacist labor cost associated with the consult adjudication; this was based on the average salary and benefits estimates of 3 pharmacists. Duration of therapy was determined based on guidelines described in Appendix B (available in online article). These methods for determining cost savings and duration of therapy were derived from an earlier study.11 When multiple therapies were recommended as alternatives, preference was given to the therapy that was ultimately prescribed when calculating direct cost savings. If the recommendation resulted in no change of therapy or the patient continued to get the requested medication through a non-VA source, then the cost of recommended therapy was considered to be zero. Descriptive statistics were used to describe baseline demographics and characterize the restricted drug consult data.

Results

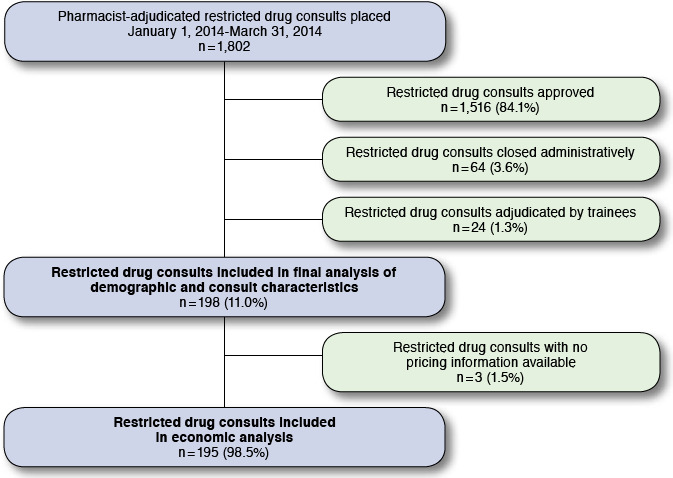

During the study period, 1,802 restricted drug consults were adjudicated by a pharmacist, including 1,703 general, 48 anticoagulation, and 51 oncology. Approval rate was 84.1% overall and varied by type of consult: 83.9% for general, 79.2% for anticoagulation, and 96.1% for oncology. A total of 198 restricted drug consults (186 general, 10 anticoagulation, and 2 oncology) for 190 individual patients met criteria for inclusion and were analyzed. Three consults requested therapy with no pricing information available and were excluded from economic analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Sample Selection Flowchart

Among patients with restricted drug consults that were not approved, most were white males over age 60 years. (Table 1). The classification of requesting provider was evenly distributed. The formulary management team adjudicated the majority of the consults (90.4%), followed by anticoagulation (5.1%), inpatient (3.5%), and oncology (1.0%). Most drugs were requested for outpatient use (92.4%), and most were nonformulary agents (82.3%). The most commonly requested drugs were rosuvastatin (11.6%), insulin pens (6.1%), tamsulosin (4.0%), varenicline (3.5%), ezetimibe (3.0%), and rivaroxaban (3.0%). The top 3 indications for requested drugs were dyslipidemia (15.2%), pain (15.2%), and diabetes (12.1%).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics and Requesting Provider Classification

| Patient demographics (n = 190) | |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 61.9 (24-93) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 161 (84.7) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 123 (64.7) |

| African American | 64 (33.7) |

| Other | 3 (1.6) |

| Requesting provider classification (n = 198) | |

| Physician, n (%) | 63 (31.8) |

| Mid-level, n (%) | 68 (34.3) |

| Nurse practitioner | 37 (18.7) |

| Physician assistant | 28 (14.1) |

| Pharmacist | 3 (1.5) |

| Medical trainee, n (%) | 67 (33.8) |

| Medical resident | 59 (29.8) |

| Medical fellow | 8 (4.0) |

Pharmacist rationale for nonapproval of restricted drug consults varied, with the most frequently cited reasons being that the patient must first trial a formulary agent; the patient does not meet the criteria for use; and safety (Table 2). Nonapproved consults that were attributed to safety included instances of missing or abnormal lab values, drug interactions, disease state contraindications to therapy, or documented previous adverse drug reaction to therapy.

TABLE 2.

Pharmacist Rationale for Nonapproval of Restricted Drug Consult (N = 198)

| Rationale Category | n (%) |

| Must trial formulary agent | 58 (29.3) |

| Does not meet criteria for use | 49 (24.7) |

| Safety | 37 (18.7) |

| Must optimize formulary agent | 13 (6.6) |

| Inadequate information provided in consult | 13 (6.6) |

| Lack of supportive efficacy data | 13 (6.6) |

| Restricted to specific service | 5 (2.5) |

| Cosmetic use | 4 (2.0) |

| Other | 6 (3.0) |

The economic analysis was based on 195 evaluable restricted drug consults (Table 3). Overall, the formulary consult review reduced the cost of therapy by 81%. After adjusting for the cost of pharmacist review for all restricted drug consults, approved and nonapproved, the total cost savings for consults that were not approved over the 3-month study period was $420,324.05. Among individual nonapproved consults, the mean cost savings was $2,384.10 (range: −$3,009.27-$65,982.36) in the outpatient setting and $373.36 (range: −$18.77-$4,644.78) in the inpatient setting. Formulary management pharmacist-adjudicated consults were associated with the largest total cost savings, while oncology pharmacist-adjudicated consults were associated with the greatest mean cost savings (Table 4). Twenty-five consults resulted in a net loss, totaling −$6,800.67.

TABLE 3.

Cost of Therapy and Cost Savings (N=195)

| Setting | Cost of Therapy ($)a | Cost Savings ($)a | |||||

| Total as Requested | Total After Consultb | Total | Mean per Consult | Median per Consult | Minimum per Consult | Maximum per Consult | |

| Outpatient (n = 180) | 531,221.63 | 102,083.21 | 429,138.42 | 2,384.10 | 267.52 | -3,009.27 | 65,982.36 |

| Inpatient (n = 15) | 5,758.10 | 157.68 | 5,600.42 | 373.36 | 13.29 | -18.77 | 4,644.78 |

| All settings (n = 195) | 536,979.73 | 102,240.89 | 434,738.84 | 2,229.43 | 254.79 | -3,009.27 | 65,982.36 |

aCost per year or specified duration.

bSummative cost of recommended therapy and cost of consult review.

TABLE 4.

Cost Savings According to Pharmacy Team Adjudicating Consult (N = 195)

| Pharmacy Team | Cost Savings ($)a,b | ||

| Total | Mean per Consult | Median per Consult | |

| Formulary management (n = 176) | 343,525.77 | 1,951.85 | 242.88 |

| Anticoagulation (n = 10) | 10,403.21 | 1,040.32 | 1,279.48 |

| [npatient (n = 7) | 1,922.10 | 274.59 | 1.98 |

| Oncology (n = 2) | 78,887.76 | 39,443.88 | 39,443.88 |

aCost per year or specified duration.

aCost savings after adjusting for cost of pharmacist review.

Discussion

The results of this study indicate that a pharmacist-adjudicated formulary consult service in an integrated health care system is associated with substantial cost savings. Over a 3-month period, 195 restricted drug consults that were not approved through pharmacist review resulted in a cost savings of $420,324.05, after accounting for the cost of pharmacist review. If the rate of consult submission and nonapproval were to remain constant, this could be extrapolated to a savings of nearly $1.7 million dollars annually. This cost savings was calculated based on VA contract pricing, which is significantly lower than average wholesale cost and most other pricing guides, which indicates that these results likely underestimate the cost savings that would be seen in most other practice settings. The largest total cost savings were seen with outpatient prescriptions, which is likely because of the longer duration of therapy and larger volume of consults.

Most consults were adjudicated by the formulary management pharmacy team, which is expected given that review of restricted drug consults constitutes a majority of this team’s workflow. In comparison, consult review represents a small portion of the inpatient, anticoagulation, and oncology pharmacy team responsibilities. These pharmacy teams also have more direct interaction with the prescribers, so it is important to note that many interventions may be made before the provider gets to the point of submitting a restricted drug consult.

Formulary management systems have been associated with cost savings, but few reports describe the outcomes of a closed formulary. The closed formulary system in the VA may be perceived as significantly restrictive. However, a survey of 1,812 VA staff physicians found that 72% of clinicians reported that their local formulary covered more than 90% of drugs they wanted to prescribe, and 86% agreed that it is important for the VA to choose “best-value” drugs.21 The VANF is developed under strict cost-effectiveness criteria rather than just based on cost considerations. The use of pharmacists to prospectively review consults for restricted drugs allows for open communication regarding appropriateness of therapy and alternate options and provides a mechanism for approval in appropriate circumstances. Even with a high approval rate, a cost savings of more than $420,000.00 was seen over a 3-month period. The fact that 25 consults had alternate recommendations resulting in a net loss demonstrates that decisions are based primarily on best available evidence and safety and secondarily on cost.

Having a formulary enforcement process in place is paramount in maintaining cost and ensuring safe and efficacious treatment options. This is especially important at academic teaching hospitals with constant turnover in medical trainees, since trainees may be unaware of the institution-specific formulary. For institutions without pharmacist-based methods of formulary enforcement, a strong starting point would be targeting a service associated with high cost savings, such as oncology or other services with high-risk medications (e.g., anticoagulation, pain, and inpatient). For institutions hoping to hire a pharmacist for the purpose of formulary management, especially in the VA or another integrated health care setting, this study provides data on direct cost savings that easily justify dedicated formulary management positions. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and cost avoidance will aid in further characterizing the effects of direct pharmacist involvement in prospective enforcement of a health system formulary. Additionally, more data on inpatient consults would provide a more robust recommendation for health care systems that do not operate as an integrated model.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. The primary limitation is that clinical outcomes and cost avoidance were not assessed. Determining clinical outcomes of pharmacists in this setting is important in considering the effects of a restrictive formulary management approach. While the direct cost savings for inpatient consults were low, it is likely that a cost avoidance analysis would reveal a larger benefit in this setting because of high costs associated with prolonged inpatient stays.11 Few consults were requested for inpatient use only, so the data provide less insight into outcomes in an inpatient setting. Another potential limitation is that current contract pricing for drugs was used; there has likely been fluctuation since the time of consult adjudication, but it is anticipated that this would have a neutral effect on cost savings. Finally, it is difficult to generalize the findings of this study to a health care system without an integrated model.

Conclusions

A pharmacist-adjudicated formulary consult service in a VA medical center was associated with a cost savings of $420,324.05 over a 3-month period, after adjustment for cost of pharmacist review. Most consults were adjudicated by formulary management pharmacists and were requested for outpatient use. Future research should assess clinical outcomes and cost avoidance associated with a restricted formulary management system, with more of an emphasis on inpatient use.

APPENDIX A. Calculations for Determining Cost of Requested and Recommended Therapy and Cost Savings 11

- Cost of requested therapy

- Calculation

- Cost of requested therapy = (daily drug acquisition cost)×(duration of therapy)

- Cost of recommended therapy

- Calculation

- Cost of recommended therapy = (daily drug acquisition cost)×(duration of therapy)

- Cost of consult review

- Calculation

- Cost of consult review = (pharmacist average hourly salary with benefits)×(average duration of time spent per consult review)

- Data for consult review

- Average annual salary with benefits: base salary ($120,000) + benefits ($40,000) = $160,000 per year

- Average hourly salary with benefits = $160,000 per year ÷ 2,080 hours per year = $76.92 per hour

- Average time to complete consult: 7 minutes

- Average cost per consult: $76.92 per 60 minutes × 7 minutes per consult = $8.97 per consult

Calculation of direct cost savings

- Calculation

- Individual nonapproved consult direct cost savings = (cost of requested therapy) – (cost of recommended therapy) – (cost of consult review)

- Overall direct cost savings = (sum of direct cost savings for individual nonapproved consults) – (cost of consult review for all other restricted drug consults)

- Sum of individual nonapproved consult direct cost savings (n = 195): $434,738.84

- Cost of consult review for all other restricted drug consults: 1,607 consults x $8.97 per consult = $14,414.79

- Overall direct cost savings = ($434,738.84) –($14,414.79) = $420,324.05

APPENDIX B. Guidelines for Determining Duration of Therapy When Calculating Cost of Requested and Recommended Therapy11

-

Scheduled medications

Long-term medications taken daily (no duration limit): 365 days

Long-term medications taken daily (with duration limit): known duration

Short-term outpatient or discharge medications: known duration

Short-term inpatient medications: known duration

-

Unscheduled medications

Outpatient or inpatient medications: known duration

References

- 1.Bryan S, Sofaer S, Siegelberg T, et al. Has the time come for cost-effectiveness analysis in U.S. health care? Health Econ Policy Law. 2009;4(Pt 4):425-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coalition of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, Alliance of Community Health Plans, American Medical Association, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Business Coalition on Health, and U.S. Pharmacopeia. Principles of a sound drug formulary system. October 2000. Available at: http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=9280. Accessed July 14, 2016.

- 3.Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. Formulary management. November 2009. Available at: http://www.amcp.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=9298. Accessed July 14, 2016.

- 4.Tyler LS, Millares M, Wilson AL, et al. ASHP guidelines on the pharmacy and therapeutics committee and the formulary system. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(13):1272-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gouveia WA, Shane R. The three dimensions of managed care pharmacy practice. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3(2):231-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boucher BA. Formulary decisions: then and now. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(6 Pt 2):35S-41S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Government Accountability Office. Report to congressional addressees. VA drug formulary: drug review process is standardized at the national level, but actions are needed to ensure timely adjudication of nonformulary drug requests. GAO-10-776:2010. August 31, 2010. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-10-776. Accessed July 14, 2016.

- 8.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VHA formulary management process. VHA Handbook 1108.08. February 26, 2009. Available at: http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2417. Accessed July 14, 2016.

- 9.Radomski TR, Good CB, Thorpe CT, et al. Variation in formulary management practices within the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(2):114-20. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.14251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman J, et al. Economic evaluation of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):128. Available at: http://accp.com/docs/positions/whitePapers/EconEvalClinPharmSvcsFinalkjsedit-gts.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Rijdt T, Willems L, Simoens S. Economic effects of clinical pharmacy interventions: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65(12):1161-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Westerlund T, Marklund B. Assessment of the clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacy interventions in drug-related problems. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2009;34(3):319-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nesbit TW, Shermock KM, Bobek MB, et al. Implementation and pharmacoeconomic analysis of a clinical staff pharmacist practice model. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(9):784-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mutnick AH, Sterba KJ, Peroutka JA, Sloan NE, Beltz EA, Sorenson MK. Cost savings and avoidance from clinical interventions. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54(4):392-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Billups SJ, Plushner SL, Olson KL, Koehler TJ, Kerzee J. Clinical and economic outcomes of conversion of simvastatin to lovastatin in a group-model health maintenance organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(8):681-86. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.8.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinnon AL, Bourne J, Blizzard S, Hunter D, Phillips C. Outcome analysis of a formulary transition from nifedipine to felodipine at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center. J Manag Care Pharm. 1999;5(5):425-28. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/abs/10.18553/jmcp.1999.5.5.425. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ajumobi AB, Vuong R, Ahaneko H. Analysis of nonformulary use of PPIs and excess drug cost in a Veterans Affair population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(1):63-67. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweet BV, Stevenson JG. Pharmacy costs associated with nonformulary drug requests. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(18):1746-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helmons PJ, Kosterink JGW, Daniels CE. Formulary compliance and pharmacy labor costs associated with systematic formulary management strategy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(5):407-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glassman PA, Good CB, Kelley ME, Bradley M, Valentino M. Physician satisfaction with formulary policies: is it access to formulary or nonformulary drugs that matters most? Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(3):209-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]