Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Migraines, Which Affect About 10% Of School-Age Children In The United States, Can Significantly Impair Quality Of Life. Despite Potential Disability, Many Children Do Not Receive Treatment Or Prophylaxis, Since Medications Specifically Approved For Children Are Significantly Less Than For Adults. There Is Also Controversy Surrounding The Apparent Widespread Practice Of Prescribing Off-Label Medications For Children With Migraines. However, Little Research Has Been Done To Identify Physician-Prescribing Patterns Of Migraine Medication For Children.

OBJECTIVE:

To Investigate The Prevalence And Pattern Of Off-Label Prescribing For Children With Migraines.

METHODS:

A Secondary Data Analysis Was Conducted Using The Pooled National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (Namcs) 2011 And 2012. Patients Aged 17 Years Or Younger With A Migraine Diagnosis Were Included. A Series Of Weighted Descriptive Analyses Were Used To Estimate The Prevalence Of Migraine Drugs Prescribed During Pediatric Office Visits. A Weighted Logistic Regression Was Constructed To Compare The Prescribing Patterns Between Off-Label And Fda-Approved Medications. Analyses Used Sas 9.4 Methodology And Incorporated Sample Weights To Adjust For The Complex Sampling Design Employed By Namcs.

RESULTS:

Of The 12.9 Million Outpatient Visits With A Migraine Diagnosis That Took Place Between 2010 And 2012, 1.2 Million Were Pediatric Visits. Females Accounted For Nearly Twice The Number Of Migraine Visits Than Males (66% Vs. 34%). Children Aged 12-17 Years Accounted For The Highest Frequency Of Visits (84%), Compared With Those Aged Under 12 Years (16%). 66.7% Of These Pediatric Patients Received At Least 1 Migraine Drug. Of These, Off-Label Medications Were Prescribed 1.5 Times More Than Fda-Approved Medications For Children (60.34% Vs. 39.65%). The Results Of Logistic Regression Showed A Significant Likelihood Of Prescribing Off-Label Medications Based On Physician Specialty, Patient Race, And Reason For Visit. Neurologists (Or = 0.028, P < 0.05) And Pediatricians (Or = 0.095, P < 0.05) Were Less Likely To Prescribe Off-Label Drugs Than General And Family Practitioners. Visits For Preventive Care (Or = 5.8, P < 0.05) And Flare-Ups From Chronic Migraines (Or = 5.0, P < 0.05) Were More Likely To Result In Off-Label Drug Prescriptions Than Visits For New Migraine Incidence.

CONCLUSIONS:

This Study Provides Significant Real-World Evidence Of The Widespread Practice Of Prescribing Off-Label Drugs To Children With Migraines. Although Medical Literature Shows That Off-Label Prescribing May Not Be Harmful, There Is A Dearth Of Research And Practice Guidelines To Help Practitioners Uphold Safety Standards And Ensure The Prescription Of Age-Appropriate Medications To Children.

What is already known about this subject

Migraines in children and adolescents cause significant discomfort and can affect quality of life.

Limited migraine medications have been specifically approved for use in children and adolescents.

There have been insufficient randomized clinical trials to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of migraine drugs in the pediatric population.

What this study adds

This is the first study to highlight off-label prescribing for children and adolescents for treatment of migraines in the real-world outpatient setting by a variety of physician specialties.

This study presents the characteristics of children and adolescents diagnosed with migraine, their treatment regimens by physician specialty, and various payer types.

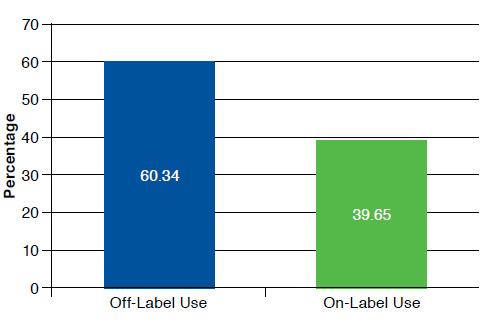

Off-label prescribing to treat pediatric migraine accounted for 60.34% of medications given, compared with on-label prescribing of 39.65%, demonstrating the high incidence of off-label prescribing for children and adolescents for the treatment of migraines.

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) defines “migraine” as the “recurring episodes of intense, pounding and nauseating head pain, which may last several hours to up to three days.”1 Migraine is a neurological disorder that is caused by a myriad of factors, including fever due to cold or flu, head injury, stress, anxiety, depression, or environmental causes such as weather changes, ingredients in food, family deposition, or other conditions such as hypertension.1 Migraine is also one of the most common recurrent headache syndromes in children and adolescents.2 According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, the prevalence of childhood migraine ranges from 1.2% to 3.2% in children aged 3-7 years; 4% to 11% for children aged 7-11 years; and 8% to 23% in adolescents aged 15 years.2

Statistics show an increasing incidence of migraine as children grow.2 Sex ratio is disproportional for children aged 3-7 years, where boys are more likely to have migraines than girls. This ratio is reversed in adolescents aged 15 years, where girls seem to have a higher prevalence of migraine than boys. For the age group 7-11 years, boys and girls have the same likelihood of developing migraines.2

The primary pathophysiology of migraines in children and adults is neuronal sensory dysfunction, which secondarily involves the trigeminal vascular systems.3 This pathophysiology can cause a range of symptoms in children. Younger children may suffer pain before they are able to talk or describe their symptoms, which could cause them to cry, vomit, or want to sleep in a dark quiet room. Older children may describe symptoms of intense, throbbing headache in the frontal lobe or sides of their heads. Symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to bright lights, and blurred vision.1 Migraine has been linked to increased disability that may lead to the inability to participate in desired activities, resulting in decreased quality of life in children.3

Because migraine can start in childhood, early correct diagnosis and effective treatment can help to reduce its effect on a child’s quality of life, thus, preventing the associated disability.4 Treatment may include nonpharmacological therapy such as massage and physical therapy or pharmacological agents such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen.

Unfortunately, because of ethical considerations in conducting clinical trials using the pediatric population, many of the pharmacological treatments approved for migraine by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have age restrictions. There is a general lack of evidence-based randomized controlled trials showing safety and efficacy for the treatment of migraine in children and adolescents.5 Acetaminophen, cyproheptadine, ibuprofen, and rizatriptan are approved by the FDA for migraines in children, and almotriptan and topiramate are only approved for children aged 12 years and older. Consequently, physicians often have to resort to off-label use of migraine medications that are not approved by the FDA.

According to the FDA, “off-label” use of medication is defined as “when a drug is used in a way that is different from that described in the FDA-approved drug label.”6 Further, it is considered off-label use if a particular medication is used for a different disease other than the approved indication or given by a different route of administration or given in a different dosage.6 With regard to off-label medication use by children with a migraine diagnosis, little research is available to show the frequency of physician-prescribed off-label medications. In an observational study of 13,426 children that analyzed factors influencing the prescribing behavior of physicians, it was found that adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years suffering from migraine were 4 times more likely to receive a drug used off-label, compared with other disease states.7

The purpose of this study was to investigate the patterns of off-label prescribing by physicians of various specialties for the treatment of migraine in children and adolescents in an ambulatory care setting.

Methods

Source of Data

A population-based cross-sectional study was conducted based on the pooled National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) 2011 and 2012. The NAMCS is a national probability sample survey conducted annually by the Division of Health Care Statistics in the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), which is under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The NAMCS samples data are collected from nonfederal office-based clinical practices. The basic sampling unit for NAMCS is the physician-patient encounter or outpatient visit. For each selected visit, physicians complete an encounter form by listing diagnoses, medication, and clinical services that they have provided. All records contain patient demographic information, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, and source of payment. The details on NAMCS sampling design is available to the public online.8

To extrapolate to national estimates, each visit record was assigned an inflation factor called the patient visit weight, which was then used to predict the total number of office visits made in the United States. All estimates from NAMCS were related to the number of patient visits and subject to sampling variability. An estimate is considered reliable if it has a relative sampling errors (SE) of ≤ 30% of the estimate, per NCHS standards. All data analyses described were performed using SAS software 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nova Southeastern University.

Data Extraction

Patients aged 17 years or younger with a diagnosis of migraine were included in this study. We identified migraine visits using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes of 346.00-346.93 for any of the possible diagnoses reported on the patient visit form. The migraine diagnosis during the office visit was categorized into 3 groups: a new onset problem, chronic problem with a flare-up incidence, and preventive care, as specified by the physician’s office. The Multum’s Lexicon Plus system was used to classify the prescription medications. The structure of the Multum database allows multiple ingredient drugs to be assigned a single generic drug code according to their generic components and therapeutic classifications. In NAMCS, up to 8 medications can be recorded for each office visit.

FDA labeling indications were used to assess proper medication usage. In this study, each patient’s index migraine drug was compared with FDA-approved labeling to determine if the patient was treated according to its approved indications. The indicated drug was also assessed for age appropriateness, according to its FDA labeling. If there were more than 1 migraine drug per patient visit, the migraine drug that was approved as an indication by FDA as the index drug was used, since we assumed that the other drugs could have been used for another indication besides migraine. An exception to this rule were drugs in the triptans drug classification. These drugs were immediately classified as the index drug because they are only approved for migraines.

Drugs that could be used to treat migraine off-label were determined by conducting a literature search and referring to the latest AAN guideline for children to determine if there was evidence of off-label use.9 The AAN guideline was compiled based on a review of 166 articles with an age qualifier of 3-18 years. We, therefore, established 3 groups for further analyses: (1) children who received no migraine therapy; (2) children who received appropriate therapy with a drug that was FDA approved for migraine and had the correct age indication; and (3) children who did not receive appropriate therapy because they either received an FDA-approved drug that did not have the correct age indication, or they received drugs that were used off-label for migraine.

Statistical Analysis

First, we performed a series of descriptive analyses to estimate the national weighted frequency of each patient’s index migraine drug by FDA indication. To obtain the national estimates, sample weight adjustments and standard error corrections were incorporated into all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. Both standard sample design variables (CSTRATM and CPSUM) were included in the SAS PROC SURVEYFREQ program to adjust for the complex sampling design employed by NAMCS. Second, a weighted logistic regression with an SAS PROC SURVEYLOGISTICS application was conducted to predict the maximum likelihood of migraine pharmacotherapy (off-label vs. FDA approved). PROC SURVEYFREQ and PROC SURVEYLOGISTICS are able to incorporate complex survey sample designs, including designs with stratification, clustering, and unequal weighting (SAS Institute, Carey, NC). Age, gender, race, payment type, physician specialty, and reason for visit were included in the model. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) were obtained after adjustment. A two-tailed statistic with a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 12.9 million outpatient visits for migraine that took place in 2011 and 2012, 1.2 million (9.3%) were pediatric visits. As shown in Table 1, females accounted for nearly twice as many migraine visits as males (65.5% vs. 34.5%). Children aged 12-17 years had the highest frequency of visits compared with children aged 6-11 years, with negligible visits by children aged 0-5 years (84.6% vs. 15.4% vs. 0%). The vast majority of pediatric patients were Caucasians (90.7%), followed by African Americans (8.0%) and others (1.3%). Most children (78.3%) were covered by private insurance, followed by Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program (8.5%) and Medicare (3.4%). The top 3 physician specialties seen were pediatrics (54.5%), neurology (22.8%), and general and family medicine (12.4%).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Children Diagnosed with Migraine

| Patient Visit Characteristics | Weighted Frequency, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| 0-5 | 0 |

| 6-11 | 188,756 (15.4) |

| 12-17 | 1,036,934 (84.6) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 803,164 (65.5) |

| Male | 422,526 (34.5) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 1,111,701 (90.7) |

| African American | 98,055 (8.0) |

| Others | 15,934 (1.3) |

| Payer type | |

| Private | 959,715 (78.3) |

| Medicare | 41,673 (3.4) |

| Medicaid/CHIP | 104,184 (8.5) |

| Self-paid | 18,385 (1.5) |

| Others | 74,767 (6.1) |

| Unknown | 26,965 (2.2) |

| Physician specialty | |

| Pediatrics | 667,649 (54.5) |

| Neurology | 279,296 (22.8) |

| General and family medicine | 152,514 (12.4) |

| Psychiatric | 30,301 (2.5) |

| Others | 95,929 (7.8) |

| Total visits | 1,225,690 |

CHIP = Children’s Health Insurance Program.

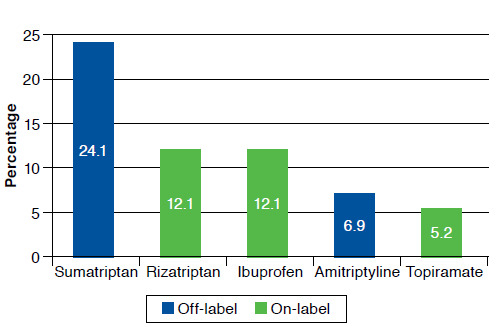

Of the 1.2 million pediatric visits with migraine diagnoses, approximately 800,000 patients (66.7%) received at least 1 migraine drug (Figure 1). The most frequently prescribed migraine drugs were sumatriptan (24.1%), rizatriptan (12.1%), ibuprofen (12.1%), amitriptyline (6.9%), and topiramate (5.2%; Figure 2). Other drugs prescribed were nortriptyline (5.1%), atenolol (3.4%), levetiracetam (3.4), eletriptan (3.4%), naproxen (1.7%), ketorolac (1.7%), methylphenidate (1.7%), valproic acid (1.7%), trazodone (1.7%), bupropion (1.7%), topiramate (1.7%), frovatriptan (1.7%), cyprohetadine (1.7%), butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine (1.7%), almotriptan (1.7%), duloxetine (1.7%), aspirin/caffeine/acetaminophen (1.7%), and zonisamide (1.7%).

FIGURE 1.

Physician-Prescribed Drug Treatment or No Drug Treatment for Children Diagnosed with Migraine

FIGURE 2.

Top 5 Most Frequently Prescribed Migraine Drugs for Children

Of the children who received at least 1 migraine drug, offlabel or age-inappropriate drugs were prescribed 1.5 times more frequently than FDA-approved medications for children (60.34% vs. 39.65%; Figure 3). Sumatriptan, the most frequently prescribed drug at 24.1%, and amitriptyline do not have FDA-approved indications for migraines in children. As mentioned earlier, rizatriptan and ibuprofen are FDA approved for migraines in children, and topiramate is only approved for children aged 12 years and older.

FIGURE 3.

On-Label/Off-Label Use of Physician-Prescribed Medication Treatment for Children Diagnosed with Migraine

Table 2 presents the significant variables associated with prescribing off-label drugs for children with migraine from the multivariate logistic regression in OR and 95% Wald confidence interval (CI). Physician specialty also matters, since neurologists (OR = 0.028; 95% CI = 0.003-0.298) and pediatricians (OR = 0.095; 95% CI = 0.013-0.691) were less likely to prescribe off-label drugs than general and family physicians. The reason for visit was also significantly associated with off-label prescribing—flare-ups from chronic migraines (OR = 5.0; 95% CI = 1.458-17.147) were 5 times more likely than a new migraine problem, and preventive care (OR = 5.795; 95% CI = 2.646-12.689) was almost 6 times as likely as a new migraine problem. In addition, it was found that African Americans were rarely prescribed off-label medication for migraines compared with Caucasians, as seen by the extremely small ORs (OR < 0.001; 95% CI ≤ 0.001 to < 0.001). Other races, who were neither Caucasian nor African American, were also 6.5 times (OR = 0.133; 95% CI = 0.056-0.315) less likely to be prescribed off-label drugs compared with Caucasians.

TABLE 2.

Significant Variables Associated with Prescribing Off-Label Drugs for Migraine in Childrena

| Variable | Adjusted OR | 95% Wald CI |

|---|---|---|

| Physician specialty | ||

| General and family practice | Reference | |

| Pediatrics | 0.095 | 0.013-0.691b |

| Neurology | 0.028 | 0.003-0.298b |

| Reason for visit | ||

| New problem | Reference | |

| Chronic problem with flare-up | 5.000 | 1.458-17.147b |

| Preventive care | 5.795 | 2.646-12.689b |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | Reference | |

| African American | < 0.001 | < 0.001-< 0.001b |

| Other | 0.133 | 0.056-0.315b |

aMultivariate logistic regression, adjusting for age, gender, race, payment type, physician specialty, and reason for visit.

bSignificant with α < 0.05.

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Discussion

This study revealed significant real-world evidence of pervasive off-label drug prescribing to children with migraines. Also, undertreatment may have been a problem, since it was found that nearly 33.3% of children with a migraine diagnosis did not receive any migraine medication during their office visits. A retrospective chart review study by Lewis et al. (2004) found that only 50% of patients with migraines were prescribed daily prophylactic medicine in a pediatric neurology clinic.5 Physicians have shown reluctance in prescribing medications that are not nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or cyproheptadine because of the lack of reliable studies, primarily to avoid harming the child. This reluctance has led to undertreatment.10 Children are also known for their inability to swallow pills, thus, requiring an alternative route of administration. This situation may also lead to undertreatment, since most migraine medications are in oral form.10 The most studied agents for the treatment of pediatric migraines are ibuprofen and acetaminophen.11 These medications are among the few to show safety and efficacy in randomized controlled trials for the treatment of migraines in children, thus, giving physicians limited options.

Results from this study showed that neurologists were 35 times less likely to prescribe off-label drugs than general and family practitioners for the management of migraines in children. Pediatricians were 10 times less likely to do so. These observations were not surprising, since specialists are generally more aware of the lack of randomized studies available for children.12 While some studies have suggested the use of triptans to treat intense episodes in children, the use of triptans for children still remains off-label, with the exception of rizatriptan and almotriptan.13,14 Attitudes towards prescribing off-label drugs also differ across physician specialty.15 A survey of 202 primary care physicians showed that 40.6% admitted to prescribing off-label drugs to children, with 23.2% claiming that no licensed alternative was available.16 Less than 15% had concerns about the risks of adverse effects and unevaluated effectiveness. Another survey was conducted with consultants and pediatric specialists, and more than half (55%) believed that the use of off-label drugs would disadvantage the children, given the lack of effectiveness and long-term safety information.17 Almost 70% of the survey participants had concerns about safety, reported high rates of treatment failure (47%), and side effects (17%). Meanwhile, over the last few years, an increasing number of tertiary multidisciplinary headache clinics for adults have been established across the globe.18 One prospective cohort study evaluated the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary team that consisted of physicians, headache nurses, physiotherapists, and psychologists in a pediatric headache clinic. The results were positive, with 50% of children experiencing an improvement in headache frequency above 50% at 6 months.19 To overcome poor treatment response rates in the pediatric population, this may be an option worth considering.

Children were 5 times more likely to receive an off-label drug when visiting their physicians for flare-ups from chronic migraine problems than children who visited their physicians for a new onset migraine treatment. Ibuprofen and acetaminophen were generally seen as first-line agents for acute migraine management because they have good safety profiles and have been shown to be significantly more effective than placebo in providing migraine relief.13,14 In our study, they also made up the bulk of on-label and appropriate migraine therapy. Unfortunately, there is a lack of efficacious drugs available to children should these medications fail. Triptans are seen as second-line abortive drugs because they are used for moderate-to-severe migraines in adults. However, most triptans are not approved by the FDA for use by children, with the exception of rizatriptan and almotriptan, which are approved for children aged older than 6 years and 12 years, respectively. Almotriptan is one of the more expensive triptans available, leaving rizatriptan as the only affordable FDA-approved second-line abortive migraine drug.

Children were also 6 times more likely to receive an off-label drug when visiting their physicians for migraine preventive care than children with new onset problems. Again, this has to do with the lack of FDA-approved drugs for the prevention of migraine in children. Just as the meta-analysis conducted in 2004,9 the more recent meta-analyses also had pessimistic views on preventive therapy in children as compared with acute therapy.13,14 Only flunarizine was proven safe and effective; however, it is not available in the United States. Studies have evaluated many other drug classes that may benefit children, such as antidepressants, antihypertensions, antiepileptic, antihistamines, and botulinum toxin, but none have clear evidence and none are approved by the FDA for migraine use in children.20 Topiramate had encouraging signs for preventive use but is currently only approved for prophylaxis of migraine in children aged 12 years and older.21 Cyproheptadine is also indicated by the FDA for migraine prevention and can be used in young children aged older than 2 years. However, based on our study data, it was rarely prescribed.

Among our sample population, African Americans and other races were significantly less likely to be prescribed offlabel medications for migraines than Caucasians. A reason for this disparity could be their respective overall use of health care services. A recent study found that African Americans were less likely than Caucasians to use the health care setting for treatment of migraines. The rate of health care setting use by African Americans was 47%, compared with Caucasians at 70%.22 In addition to this underuse of health care services, the study also reported that African Americans had more mistrust and a lower quality of communication towards the health care system than Caucasians. The prevalence of migraines might also differ between the races. Compared with Caucasians, African American children tend to report lower rates of migraine, leading to a lesser need to prescribe medications.23

Another reason for the racial disparity found among children diagnosed with migraines was the lack of health insurance among other races. Wide disparity in health care coverage exists across ethnic groups. According to the Institute of Medicine, African Americans were twice as likely to be uninsured as Caucasians, and Hispanics were 3 times as likely to be uninsured.24 The lack of health insurance coverage between non-Caucasian races can be attributed to differences in socioeconomic status. As a result of their lower socioeconomic status, non-Caucasian races were more likely to have jobs that did not offer health benefits, making them less likely to be able to afford private health coverage.25

Limitations

This study has several limitations that need to be considered. First, we did not make use of the latest AAN guideline to determine the appropriate migraine medication use. The guideline was last published in 2004 and, at the point of this writing, was undergoing an update. Many of the drugs in the guideline were also not proven to be safe and effective for children. As stated in the guideline, “Failure of an agent for acute or preventive therapy to demonstrate significant efficacy does not imply that the drug has no role in the pediatric population.”9 Even in more recent meta-analysis studies,13,14 results mirrored the guidelines in that there were no upcoming drugs that were safe and effective for the pediatric population, in addition to those with FDA approval. Because of the subjective manner of the guidelines and meta-analysis studies, the FDA’s labeling was used to provide a more objective source of a drug’s appropriateness for children.

Second, use of the NAMCS database limited the results to cross-sectional data, so tracking and follow-up were not possible. So, beyond the episodic diagnoses by physicians during office visits, there were no other clinical objective measures or independent confirmation of the migraine diagnoses. Also, diagnosing migraines in children can be difficult because of its nonspecific symptoms, so there could have been nondifferential misclassification of diagnosis. In spite of that, the data were at least as accurate as other prevalence studies that made use of self-reported surveys for migraine diagnosis. These surveys would be even less accurate than a physician’s diagnosis.

Finally, despite national estimates of 250,000 visits to the emergency room for headaches yearly,26 the NAMCS database only included outpatient visits for migraine and did not include children’s visits to the emergency room.

Conclusions

This study provided significant real-world evidence that offlabel prescribing is widespread for children with migraines. Although numerous studies in the literature have reported that off-label prescribing may not always be harmful, there is a need for more research and practice guidelines to guide physicians in prescribing age-appropriate migraine medications to children.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Neurology.. AAN guideline summary for patients, parents, and caregivers. Treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents. December 28, 2004. Available at: http://tools.aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/headache_peds_patients.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2017.

- 2.Steward WF, Linet MS, Celentano DD, Van Natta M, Ziegler D.. Age- and sex-specific incidence rates of migraine with and without visual aura. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(10):1111-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hargreaves RJ, Shepheard SL.. Pathophysiology of migraine—new insights. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26(Suppl 3):12-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winner P. Pediatric headache. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21(3):316-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis DW, Diamond S, Scott D, Jones V.. Prophylactic treatment of pediatric migraine. Headache. 2004;44(3):230-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry.. Distributing scientific and medical publications on unapproved new uses—recommended practices. February 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidancecomplianceregulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm387652.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2017.

- 7.‘t Jong GW, Eland IA, Sturkenboom MC, van den Anker JN, Stricker BH.. Determinants for drug prescribing to children below the minimum licensed age. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;58(10):701-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.. NAMCS scope and sample design. November 6, 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_scope.htm. Accessed January 26, 2017.

- 9.Lewis D, Ashwal S, Hershey A, Hirtz D, Yonker M, Silberstein S.. Practice parameter: pharmacological treatment of migraine headache in children and adolescents. Report of the American Academy of Neurology Quality Standards Subcommittee and the Practice Committee of the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2215-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yonker ME. Pharmacologic treatment of migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2006;10(5):377-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamalainen ML, Hoppu K, Valkeila E, Santavuori P.. Ibuprofen or acetaminophen for the acute treatment of migraine in children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Neurology. 1997;48(1):103-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhatt K, Malhotra S, Patel K, Patel V.. Drug utilization in pediatric neurology outpatient department: a prospective study at a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Basic Clin Pharma. 2014;5(3):68-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonfert M, Straube A, Schroeder A, Reilich P, Ebinger F, Heinen F.. Primary headache in children and adolescents: update on pharmacotherapy of migraine and tension-type headache. Neuropediatrics. 2013;44(1):3-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Toldo I, Carlo DD, Bolzonella B, Sartori S, Battistella PA.. The pharmacological treatment of migraine in children and adolescents: an overview. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12(9):1133-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuzzolin L, Atzei A, Fanos V.. Off-label and unlicensed prescribing for new-borns and children in different settings: a review of the literature and a consideration about drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5(5):703-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ekins-Daukes S, Helms PJ, Taylor MW, Mclay JS.. Off-label prescribing to children: attitudes and experience of general practitioners. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;60(2):145-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mclay JS, Tanaka M, Ekins-Daukes S, Helms PJ.. A prospective questionnaire assessment of attitudes and experiences of off label prescribing among hospital based paediatricians. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(7):584-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunreben-Stempfle B, Gressinger N, Lang E, Muehlhans B, Sittl R, Ulrich K.. Effectiveness of an intensive multidisciplinary headache treatment program. Headache. 2009;49(7):990-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soee A-BL, Skov L, Skovgaard LT, Thomsen LL.. Headache in children: effectiveness of multidisciplinary treatment in a tertiary paediatric headache clinic. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(15):1218-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hickman C, Lewis KS, Little R, Rastogi RG, Yonker M.. Prevention for pediatric and adolescent migraine. Headache. 2015;55(10):1371-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis D, Winner P, Saper J, et al.. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topiramate for migraine prevention in pediatric subjects 12 to 17 years of age. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):924-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson RA, Rooney M, Vo K, O’laughlin E, Gordon M.. Migraine care among different ethnicities: do disparities exist? Headache. 2006;46(5):754-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bigal M, Lipton R, Winner P, Reed M, Diamond S, Stewart W.. Migraine in adolescents: association with socioeconomic status and family history. Neurology. 2007;69(1):16-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirby JB, Kaneda T.. Unhealthy and uninsured: exploring racial differences in health and health insurance coverage using a life table approach. Demography. 2010;47(4):1035-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catanzarite L. Race-gender composition and occupational pay degradation. Soc Probl. 2003;50(1):14-37. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kedia S, Ginde AA, Grubenhoff JA, Kempe A, Hershey AD, Powers SW.. Monthly variation of United States pediatric headache emergency department visits. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(6):473-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]