Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The treatment of postsurgical pain with prescription opioids has been associated with persistent opioid use and increased health care utilization and costs.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the health care burden between opioid-naive adult patients who were prescribed opioids after a major surgery and opioidnaive adult patients who were not prescribed opioids.

METHODS:

Administrative claims data from the IBM Watson Health MarketScan Research Databases for 2010-2016 were used. Opioid-naive adult patients who underwent major inpatient or outpatient surgery and who had at least 1 year of continuous enrollment before and after the index surgery date were eligible for inclusion. Cohorts were defined based on an opioid pharmacy claim between 7 days before index surgery and 1 year after index surgery (opioid use during surgery and inpatient use were not available). To ensure an opioid-naive population, patients with opioid claims between 365 and 8 days before surgery were excluded. Acute medical outcomes, opioid utilization, health care utilization, and costs were measured during the post-index period (index surgery hospitalization and day of index outpatient surgery not included). Predicted costs were estimated from multivariable log-linked gamma-generalized linear models.

RESULTS:

The final sample consisted of 1,174,905 opioid-naive patients with an inpatient surgery (73% commercial, 20% Medicare, 7% Medicaid) and 2,930,216 opioid-naive patients with an outpatient surgery (74% commercial, 23% Medicare, and 3% Medicaid). Opioid use after discharge was common among all 3 payer types but was less common among Medicare patients (63% inpatient/43% outpatient) than patients with commercial (80% inpatient/75% outpatient) or Medicaid insurance (86% inpatient/81% outpatient). Across all 3 payers, opioid users were younger, were more likely to be female, and had a higher preoperative comorbidity burden than nonopioid users. In unadjusted analyses, opioid users tended to have more hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and pharmacy claims. Adjusted predicted 1-year post-period total health care costs were significantly higher (P< 0.001) for opioid users than nonopioid users for commercial insurance (inpatient: $22,209 vs. $14,439; outpatient: $13,897 vs. $8,825), Medicare (inpatient: $31,721 vs. $26,761; outpatient: $24,529 vs. $15,225), and Medicaid (inpatient: $13,512 vs. $9,204; outpatient: $11,975 vs. $8,212).

CONCLUSIONS:

Filling an outpatient opioid prescription (vs. no opioid prescription) in the 1 year after inpatient or outpatient surgery was associated with increased health care utilization and costs across all payers.

What is already known about this subject

Opioids are commonly prescribed for treating acute postsurgical pain. Studies have reported that postsurgical opioid use can lead to persistent opioid use in opioid-naive patients.

Evidence on the economic burden of postsurgical opioid use in the management of acute postsurgical pain remains limited.

What this study adds

This study showed that filling an outpatient prescription for opioids in the 1 year after a major inpatient or outpatient surgery was associated with increased health care costs and utilization across all payers.

Patients treated with opioids after an inpatient surgery were more likely to have subsequent surgeries and persistent postsurgical pain within a year; however, Medicare and Medicaid patients filling opioids were less likely to have a hospital readmission.

Those treated with opioids after an outpatient surgery were more likely to have persistent postsurgical pain and hospitalizations within 90 days; however, those filling prescriptions for opioids were less likely to have a subsequent surgery in the next year than their nonopioid counterparts.

Postsurgical pain is a prevalent condition following surgical procedures.1 Estimates suggest that postsurgical pain affects over 80% of patients who undergo surgery, and 10%-50% report persistent pain that lasts for 3-6 months postsurgery after common procedures.2-4 Postsurgical pain is often poorly managed in the majority of patients in the United States, leading to an array of physiologic and psychologic consequences, including increased morbidity, impaired quality of life, delayed recovery time, prolonged opioid use, and increased health care cost.1 Management is primarily aimed at alleviating pain, maximizing functional ability, minimizing side effects, and improving quality of life.5

Estimates suggest that between 49% and 95% of patients who undergo surgery are discharged with an opioid prescription.6-8 A sizeable proportion of opioid-naive patients who receive opioids after surgery become persistent opioid users (i.e., continued opioid fills for more than 3 months).9-12 Persistent opioid use after surgery negatively affects patients’ quality of life and may lead to opioid abuse and increased health care utilization and costs.13-15 Furthermore, the increasing opioid prescription rate coupled with reports that up to 92% of patients have unused postsurgical prescription opioids in their possession highlight the concern that unintended populations could gain access to prescription opioids.16-18

The clinical and economic implications of opioid use before and after surgery in the management of acute postsurgical pain is well documented.19-26 However, there is a dearth of real-world studies that specifically compare health outcomes among opioid-naive surgery patients with opioid use following discharge from surgery versus such patients who did not receive opioids.14 To our knowledge, only 1 study, published in 2016, has evaluated a similar research question. Gold et al. (2016) found that patients undergoing joint replacement surgery who received long-acting opioids within 30 days of surgery had significantly longer lengths of inpatient hospitalization and greater health care use and costs over 12 months of follow-up compared with patients whose pain was managed without long-acting opioids.14

Given the association between opioid use following surgery and persistent opioid use, it is important to quantify the health care burden posed by persistent opioid use among opioidnaive surgery patients who received prescription opioids after discharge. This retrospective cohort study was conducted to assess medical outcomes, health care utilization, and costs among opioid-naive patients who received prescription opioids compared with those who did not receive opioids after surgery, using a large, nationally representative claims database.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This retrospective observational cohort study used health care claims data from the IBM Watson Health Commercial Claims and Encounters (commercial), MarketScan Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits (Medicare), and Medicaid Multi-State (Medicaid) databases. The commercial database includes fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims for over 147 million individuals, covered annually by a geographically diverse group of self-insured employers and private insurance plans across the United States. The Medicare database contains health care experience (medical and pharmacy) of approximately 10.2 million individuals with Medicare supplemental insurance paid for by employers between 1995 and 2016. The Medicaid database contains the pooled health care experience of approximately 44.2 million Medicaid enrollees between 1999 and 2015 from multiple geographically dispersed state programs.

The study databases satisfy the conditions set forth in Sections 164.514 (a)-(b)1ii of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 privacy rule regarding the determination and documentation of statistically deidentified data. Because this study used only deidentified patient records, it was exempted from institutional review board review or approval.

Patient Selection and Study Cohorts

Adults (18 years or older) with evidence of major therapeutic or diagnostic procedure (except those related to coronary artery bypass grafting) as defined by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project between January 1, 2010, and September 30, 2016 (commercial, Medicare) or December 31, 2016 (Medicaid) were identified.27 Two separate samples were created for patients with inpatient surgical procedures and those with outpatient procedures. Patients with commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid coverage were analyzed separately for each surgical setting. The index date was the date of discharge of first hospitalization with surgery for the inpatient surgery cohort and the date of first outpatient surgery for the outpatient surgery cohort. For patients with evidence of both inpatient and outpatient surgery or multiple surgeries, the earliest surgery was considered the index date. All patients were required to have continuous medical and pharmacy coverage for at least 12 months before (baseline period) and after the index date (follow-up period). Patients were excluded if their claims records indicated the following:

Outpatient pharmacy claims for opioids from 12 months through 8 days before the index date, to isolate an opioidnaive population

Opioid dependence, abuse, or overdose or treatment for dependence, abuse, or overdose in the 12 months before the index date based on prescription claims and diagnosis and procedure codes

Evidence of inpatient or outpatient surgery in the 12 months before the index date based on procedure codes

Dual coverage by Medicare and Medicaid

Study Cohorts

Patients were stratified into opioid users and nonopioid users based on the presence of at least 1 outpatient pharmacy claim with a National Drug Code (NDC) number for an opioid between 7 days before admission date (inpatient) or date of surgery (outpatient) and 365 days after the index date. Opioids included fentanyl, hydromorphone, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, meperidine, oxymorphone, levorphanol tartrate, codeine, tramadol, dihydrocodeine, tapentadol, hydrocodone, propoxyphene, sufentanil, remifentanil, and buprenorphine. The majority of claims for buprenorphine and methadone did not occur after an abuse or dependence diagnosis, indicating that they were likely used for treatment of pain.

Outcome Measures

Outcomes measured over the 1-year follow-up period included health care utilization and costs, medical outcomes, and opioid utilization. Outcomes were defined a priori.

Health Care Utilization and Costs.

All-cause health care utilization and costs by type of service (inpatient; outpatient [emergency department {ED}, outpatient office visits, ambulance/paramedic, and other outpatient care]; pharmaceutical; total medical [inpatient + outpatient costs]; and total health care [total medical + pharmaceutical costs]) were determined for each cohort over the 1-year period after the index surgery (index admission for inpatient surgery/day of outpatient surgery not included). Health care costs were based on paid amounts of adjudicated claims, including insurer payments and patient cost sharing in the form of copayments, deductibles, and coinsurance, and were inflation-adjusted to 2017 U.S. dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.

Medical Outcomes.

The percentage of patients with a claim for postsurgical pain (based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 338.12, 338.18, 338.22, and 338.28 or Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-10-CM] codes G89.12, G89.18, G89.22, and G89.28) during the 90 days after surgery were identified. The proportion of patients with hospital readmissions (inpatient surgery cohort) or hospital admissions (outpatient surgery cohort) up to 90 days after index surgery were examined. The proportion of patients with a subsequent surgery over the 1-year post-index period was assessed.

Opioid Utilization.

The percentage of patients with opioid claims within 7 days before through 1 year after inpatient or outpatient surgery based on prescription claims was measured. This time frame captures patients who received opioids immediately after their surgery, those who may have been experiencing postoperative pain and could have received opioids later, and possible persistent users.

Study Covariates

Patient demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race (available for Medicaid only), geographic region (available for commercial/Medicare only), and type of insurance plan (basic/major medical, comprehensive, exclusive provider organization, health maintenance organization, preferred provider organization, point of service, point of service with capitation, consumer-directed health plan, high-deductible health plan, and unknown/other), were captured on the index date. Surgery characteristics reported were type of surgery (general surgery, orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, obstetrical/gynecological surgery, and other) and provider specialty for the index surgery. Clinical characteristics, including the Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index (DCI); comorbid conditions (chronic pain, substance abuse, psychological comorbidities, and others as indicated by ICD-9/10-CM codes on patient claims); and use of concomitant medications (antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics [specifically benzodiazepines], and gabapentinoids, as indicated by NDC numbers or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes in patient claims), were measured during the 12-month baseline period.

Statistical Analyses

Bivariate descriptive analyses were conducted on all study outcomes, stratified by cohort (opioid users and nonopioid users). All outcomes were additionally stratified by surgical setting (inpatient and outpatient) and payer type (commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid). Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations; categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Statistical comparisons were evaluated using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous measures. A critical value of 0.05 was considered a priori as the threshold for statistical significance.

Multivariable analyses were conducted using generalized linear models with gamma-distributed error and a log link to detect whether opioid use postsurgery was associated with higher postsurgery total health care, medical, and pharmacy costs in the inpatient and outpatient surgery cohorts for each payer. Variance inflation factors were examined for all predictors and suggested no evidence of collinearity. A large portion of postsurgery total health care and medical costs was $0 for the Medicaid population and was also $0 for postsurgery pharmacy costs for all populations. For these cases, a 2-part modeling approach was used to estimate the predicted probability of incurring these costs and the estimated costs among patients who incurred at least some costs.

All models were adjusted for the following covariates: mean age; plan type; index year; geographic region; DCI; type of surgery; comorbidities (chronic pain, substance abuse, psychological comorbidities, cardiovascular disease, morbid obesity, pulmonary disease, and sleep apnea/other sleep disorders); use of antidepressants, anxiolytics, and gabapentinoids; and all-cause health care costs over the 12-month presurgical baseline period ($1-$999, $1,000-$1,999, $2,000-$2,999, $3,000-$3,999, $4,000-$4,999, $5,000-$6,999, $7,000-$8,999, $9,000-$12,999, $13,000-$20,999, and ≥ $21,000). The recycled prediction method was used to predict adjusted costs on the dollar scale. When a 2-part model was used, average costs were estimated as the probability of incurring any costs multiplied by the predicted costs. Bootstrap resampling was used to estimate standard errors.

Results

Sample Selection

The inpatient surgery cohort consisted of 852,349 commercially insured (opioid users: 80.4%; nonopioid users: 19.6%), 236,433 Medicare (opioid users: 63.3%; nonopioid users: 36.7%), and 86,123 Medicaid (opioid users: 85.9%; nonopioid users: 14.1%) patients (attrition table available upon request). Of patients who received an outpatient prescription for opioids after an inpatient surgery, the majority (90.8% commercial; 65.9% Medicare; 88.1% Medicaid) filled their initial prescription between 7 days before admission and 7 days after discharge.

The outpatient surgery cohort included 2,177,691 patients with commercial insurance (opioid users: 75.0%; nonopioid users: 25.0%), 659,888 patients with Medicare insurance (opioid users: 42.8%; nonopioid users: 57.2%), and 92,637 patients with Medicaid coverage (opioid users: 81.5%; nonopioid users: 18.6%; attrition table available upon request). Of patients who received an outpatient opioid prescription after an outpatient surgery, the majority (89.8% commercial; 58.5% Medicare; 85.8% Medicaid) filled their initial prescription between 7 days before and 7 days after surgery.

Patient Characteristics

In the inpatient surgery cohort, opioid users were significantly younger and were more likely to be female compared with nonopioid users in the commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid populations. The prevalence of chronic pain in the 12-month presurgical baseline period was significantly higher among opioid users than nonopioid users (commercial: 34.5% vs. 26.8%; Medicare: 59.5% vs. 45.3%; Medicaid: 30.9% vs. 24.0%; all P < 0.001). With certain exceptions, the prevalence of other baseline comorbidities (psychological comorbidities, sleep apnea/other sleep disorders, and pulmonary disease) was significantly higher in opioid users than nonopioid users (Table 1). Obstetric/gynecological procedures were the most common surgery type in the commercial (opioid users: 37.9%; nonopioid users: 30.6%) and Medicaid populations (opioid users: 43.2%; nonopioid users: 26.1%), and orthopedic surgeries were most common in the Medicare population (opioid users: 62.2%; nonopioid users: 37.0%). Across the 3 payers, opioid users had a significantly higher prevalence of general, obstetric/gynecologic, orthopedic, or plastic surgeries during the index admission than nonopioid users (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients in the Inpatient and Outpatient Surgery Cohorts, Stratified by Opioid Use

| Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids Postsurgery | No Opioids Postsurgery | Opioids Postsurgery | No Opioids Postsurgery | Opioids Postsurgery | No Opioids Postsurgery | |

| Inpatient surgery cohort, n | 685,592 | 166,757 | 149,717 | 86,716 | 74,001 | 12,122 |

| Mean age (SD) | 43.4 (12.7) | 45.2 (12.9)a | 74.8 (7.0) | 77.8 (7.7)a | 32.1 (12.7) | 36.4 (15.2)a |

| Females, n (%) | 479,627 (70.0) | 102,894 (61.7)a | 76,337 (51.0) | 43,357 (50.0)a | 63,288 (85.5) | 8,771 (72.4)a |

| Mean DCI (SD) | 0.49 (1.14) | 0.52 (1.15)a | 1.45 (1.79) | 1.55 (1.81)a | 0.47 (1.17) | 0.61 (1.36)a |

| Selected comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Chronic pain | 236,539 (34.5) | 44,742 (26.8)a | 89,018 (59.5) | 39,287 (45.3)a | 22,834 (30.9) | 2,908 (24.0)a |

| Cardiovascular diseaseb | 201,505 (29.4) | 55,387 (33.2)a | 113,768 (76.0) | 66,936 (77.2)a | 15,997 (21.6) | 3,458 (28.5)a |

| Psychological comorbidities | 85,184 (12.4) | 16,025 (9.6)a | 14,153 (9.5) | 8,064 (9.3) | 16,381 (22.1) | 2,484 (20.5)a |

| Sleep apnea/other sleep disorders | 56,304 (8.2) | 11,016 (6.6)a | 13,785 (9.2) | 6,140 (7.1)a | 3,953 (5.3) | 614 (5.1) |

| Pulmonary disease | 47,933 (7.0) | 11,009 (6.6)a | 22,185 (14.8) | 12,800 (14.8) | 10,094 (13.6) | 1,534 (12.7)c |

| Outpatient surgery cohort, n | 1,633,722 | 543,969 | 282,702 | 377,186 | 75,454 | 17,183 |

| Mean age (SD) | 45.5 (12.4) | 49.5 (11.6)a | 74.3 (6.8) | 76.4 (7.1)a | 36.6 (13.5) | 44.2 (16.7)a |

| Females, n (%) | 935,950 (57.3) | 310,776 (57.1%)c | 145,631 (51.5) | 207,077 (54.9)a | 56,804 (75.3) | 11,222 (65.3)a |

| Mean DCI (SD) | 0.36 (0.92) | 0.42 (0.98)a | 1.29 (1.69) | 1.15 (1.57)a | 0.46 (1.13) | 0.69 (1.34)a |

| Selected comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Chronic pain | 738,383 (45.2) | 179,754 (33.0)a | 143,160 (50.6) | 140,512 (37.3)a | 25,767 (34.2) | 4,400 (25.6)a |

| Cardiovascular diseaseb | 444,811 (27.2) | 161,704 (29.7)a | 202,785 (71.7) | 263,173 (69.8)a | 19,554 (25.9) | 6,418 (37.4)a |

| Psychological comorbidities | 216,377 (13.2) | 56,518 (10.4)a | 25,782 (9.1) | 29,828 (7.9)a | 18,841 (25.0) | 3,662 (21.3)a |

| Sleep apnea/other sleep disorders | 140,188 (8.6) | 36,616 (6.7)a | 25,879 (9.2) | 24,996 (6.6)a | 5,398 (7.2) | 995 (5.8)a |

| Pulmonary disease | 111,321 (6.8) | 32,435 (6.0)a | 38,738 (13.7) | 45,258 (12.0)a | 8,947 (11.9) | 1,947 (11.3) |

aP < 0.001; all comparisons for opioid vs. no opioid use after surgery.

bDoes not include heart failure.

cP < 0.05.

DCI = Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index; SD = standard deviation.

Similar to the trends observed in the inpatient surgery cohort, opioid users in the outpatient surgery cohort were significantly younger and more likely to be female compared with nonopioid users for all 3 payers. The prevalence of comorbidities followed the same pattern as those observed in the inpatient surgery cohort. More than half of opioid users (53.8%-77.1%) and over 3 quarters of nonopioid users (79.4%-95.6%) had other outpatient surgical procedures (i.e., not a general, obstetric/gynecological, orthopedic, or plastic surgery) at index (Table 1). All specific types of outpatient surgery (general, obstetric/gynecological, orthopedic, and plastic) were significantly more common among opioid users than nonopioid users in all payer populations (data not shown).

Health Care Utilization and Costs

In the inpatient surgery cohort, opioid users tended to have more hospitalizations, ED visits, and pharmacy claims than nonopioid users (Table 2; all P< 0.05). Use of ambulance/paramedic services after surgery was less frequent among opioid users compared with nonopioid users (commercial: 4.3% vs. 4.5%; Medicare: 18.1% vs. 22.5%; Medicaid: 14.8% vs. 17.1%; all P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Health Care Utilization and Costs Among Opioid Users Versus Nonopioid Users During the 1-Year Post-Index Period for Patients in the Inpatient Surgery Cohort

| Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opioids Postsurgery (n=685,592) | No Opioids Postsurgery (n=166,757) | Opioids Postsurgery (n=149,717) | No Opioids Postsurgery (n=86,716) | Opioids Postsurgery (n=74,001) | No Opioids Postsurgery (n=12,122) | |

| Health care utilization over 1-year post-index period, n (%) | ||||||

| Inpatient admissions | 89,561 (13.1) | 16,907 (10.1)a | 37,586 (25.1) | 19,264 (22.2)a | 11,628 (15.7) | 2,016 (16.6)b |

| Ambulance/paramedic services | 29,432 (4.3) | 7,545 (4.5)a | 27,025 (18.1) | 19,540 (22.5)a | 10,918 (14.8) | 2,067 (17.1)a |

| ED visits | 162,367 (23.7) | 32,964 (19.8)a | 54,242 (36.2) | 30,504 (35.2)a | 38,789 (52.4) | 4,590 (37.9)a |

| Pharmacy prescriptions | 649,833 (94.8) | 127,755 (76.6)a | 148,510 (99.2) | 76,079 (87.7)a | 69,374 (93.8) | 9,214 (76.0)a |

| Health care costs, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Inpatient admissions | ||||||

| Index admission | 31,525 (51,198) | 35,149 (62,914)a | 35,382 (50,425) | 39,195 (60,782)a | 14,773 (49,549) | 25,670 (71,592)a |

| 1-year post-index | 6,192 (35,749) | 4,964 (41,734)a | 8,608 (37,275) | 7,563 (37,422)a | 4,693 (38,989) | 6,404 (38,569)a |

| Outpatient services | ||||||

| Index admission | 873 (3,946) | 1,034 (4,127)a | 955 (3,437) | 1,391 (4,303)a | 150 (716) | 208 (1,166)a |

| 1-year post-index | 11,411 (33,307) | 9,202 (30,163)a | 18,255 (43,086) | 17,181 (46,326)a | 4,278 (13,548) | 6,536 (21,647)a |

| Total medical costs | ||||||

| Index admission | 32,399 (52,088) | 36,182 (63,875)a | 36,337 (50,883) | 40,585 (61,292)a | 14,923 (49,651) | 25,878 (71,772)a |

| 1-year post-index | 17,603 (54,686) | 14,166 (55,530)a | 26,863 (62,297) | 24,744 (63,554)a | 8,971 (43,207) | 12,940 (47,027)a |

| Pharmacy prescriptions | ||||||

| Index admission | 72 (430) | 67 (423)a | 80 (339) | 58 (262)a | 44 (686) | 55 (475) |

| 1-year post-index | 2,174 (9,155) | 2,151 (8,080) | 3,702 (7,930) | 3,220 (7,238)a | 1,515 (7,991) | 2,001 (7,517)a |

| Total health care costs | ||||||

| Index admission | 32,470 (52,148) | 36,249 (63,918)a | 36,418 (50,905) | 40,644 (61,307)a | 14,967 (49,703) | 25,933 (71,815)a |

| 1-year post-index | 19,777 (57,089) | 16,317 (57,233)a | 30,565 (63,642) | 27,964 (64,411)a | 10,486 (45,215) | 14,941 (49,170)a |

aP < 0.001; all comparisons for opioid vs. no opioid use after surgery.

bP < 0.05.

ED = emergency department; SD = standard deviation.

In the outpatient surgery cohort, the percentages of patients incurring inpatient admissions, ambulance/paramedic services, ED visits, or pharmacy prescriptions were all higher among opioid users than nonopioid users across all payers (all P < 0.001). The proportion of Medicaid opioid users with ED visits was almost double that of their nonopioid counterparts (Appendix A, available in online article).

For patients with an inpatient index surgery, unadjusted mean all-cause total health care costs during the 1-year postindex period were significantly higher for opioid users than for nonopioid users (commercial: $19,777 vs. $16,317; Medicare: $30,565 vs. $27,964; both P < 0.001). Medical costs accounted for 85% of total health care costs. Other outpatient care costs contributed more than half of the medical costs in both opioid users and nonopioid users. Among Medicaid patients, mean allcause total health care costs were significantly lower in opioid users than nonopioid users ($10,486 vs. $14,941; P < 0.001). Direct medical costs accounted for 85.6% and 86.6% of total costs among opioid users and nonopioid users, respectively. Inpatient admission costs (opioid users: 47.7%; nonopioid users: 50.5%) followed by other outpatient care costs (opioid users: 40.6%; nonopioid users) represented the largest drivers of medical costs in both cohorts.

Mean pharmacy costs were comparable for commercially insured opioid and nonopioid users, were significantly higher for opioid users than for nonopioid users in the Medicare population, and were significantly lower for opioid users than for nonopioid users in the Medicaid population (Table 2).

In the outpatient surgery cohort, analogous trends were observed. Mean unadjusted total health care costs were significantly higher for opioid users than for nonopioid users (commercial: $12,854 vs. $8,838; Medicare: $24,699 vs. $15,040; both P < 0.001), whereas nonopioid users incurred significantly higher costs than opioid users in the Medicaid population ($9,831 vs. $11,467; P < 0.001). Medical costs contributed to the majority (78.7%-85.8%) of total health care costs. Costs for other outpatient services (57.6%-72.5%) followed by inpatient hospitalization (16.5%-34.1%) were the largest cost components across all the cohorts. Mean pharmacy costs were similar between opioid users and nonopioid users across all payer types (Appendix A).

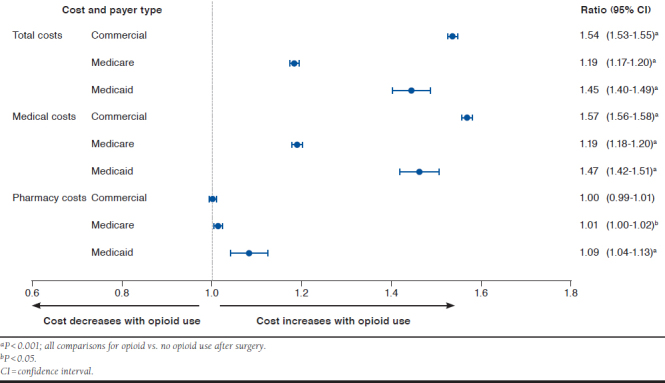

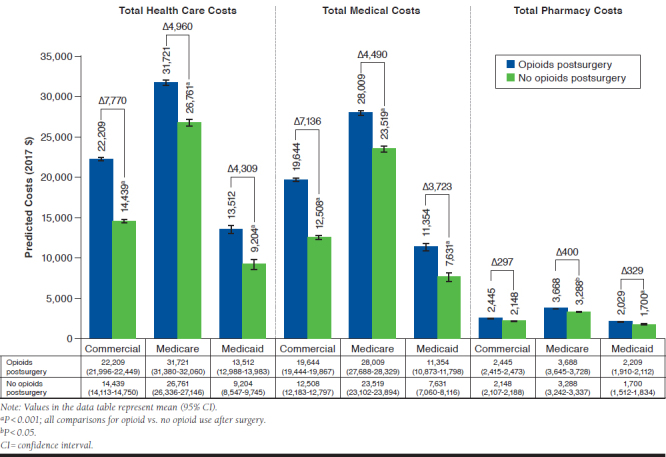

After adjusting for baseline characteristics, commercially insured patients who received opioids after an inpatient index surgery had 54% (adjusted cost ratio [95% confidence interval {CI}]: 1.54 [1.53-1.55]) higher total health care costs than those who did not receive opioids. Similarly, Medicare and Medicaid opioid users had 19% (1.19 [1.17-1.20]) and 45% (1.45 [1.40-1.49]) higher total health care costs than nonopioid users, respectively (Figure 1). Accordingly, the adjusted predicted 1-year post-index period costs were significantly higher for opioid users versus nonopioid users, with an incremental cost difference of $7,770 in the commercial cohort, $4,960 in the Medicare cohort, and $4,309 in the Medicaid cohort (all P < 0.001). The differences in costs were primarily driven by medical costs (Figure 2). The corresponding adjusted health care costs in the outpatient surgery cohort were consistent with the findings from the inpatient surgery cohort (Appendix B, available in online article). Commercially insured, Medicare, and Medicaid opioid users had 58% (adjusted cost ratio [95% CI]: 1.58 [1.57-1.58]), 61% (1.61 [1.60-1.62]), and 44% (1.44 [1.41-1.48]) higher total health care costs than nonopioid users, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Multivariable-Adjusted Cost Ratios for Opioid Users Versus Nonopioid Users Among Patients in the Inpatient Surgery Cohort

FIGURE 2.

Multivariable-Adjusted Predicted Cost for Opioid Users Versus Nonopioid Users Among Patients in the Inpatient Surgery Cohort

Medical Outcomes

Across all 3 payer types, unadjusted analyses showed that the proportions of patients with subsequent surgeries within 1 year (commercial: 17.6% vs. 9.1%; Medicare: 32.2% vs. 21.4%; Medicaid: 14.9% vs. 7.7%; all P < 0.001) and persistent postsurgical pain during the 90 days following surgery (commercial: 1.9% vs. 0.7%; Medicare: 2.5% vs. 1.2%; Medicaid: 2.8% vs. 0.7%; all P< 0.001) were significantly higher among opioid users than nonopioid users. Readmissions within 90 days postsurgery were significantly lower in opioid users across Medicare (26.3% vs. 29.3%; P < 0.001) and Medicaid patients (11.1% vs. 13.4%; P < 0.001) and significantly higher in commercially insured opioid users (10.1% vs. 9.3%; P < 0.001) compared with nonopioid users (Figure 3). In the outpatient surgery cohort, opioid users more commonly experienced persistent postsurgical pain and hospital admissions within 90 days but were less apt to have a subsequent surgery within 1 year from the index surgery compared with nonopioid users (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Medical Outcomes Among Opioid Users Versus Nonopioid Users During i-Year Post-Index Period Among Patients in the Inpatient Surgery Cohort

Opioid Utilization

Hydrocodone (32.7%-43.5% of patients, depending on payer type and surgical cohort) and oxycodone (15.3%-35.6% of patients) were the most commonly filled opioid prescriptions during the 1-year post-index period across inpatient and outpatient surgery cohorts.

Of those patients receiving opioid prescriptions after an inpatient surgery, approximately half filled 2 or more opioid prescriptions in the year after surgery (commercial: 46.8%; Medicare: 53.7%; Medicaid: 52.9%). Between 20% and 40% filled an opioid prescription between 90 and 180 days after their procedure (commercial: 23.1%; Medicare: 34.7%; Medicaid: 40.2%). Similar trends were observed in the outpatient surgery group (data not shown).

Discussion

This claims-based analysis compared medical outcomes and health care utilization and costs among opioid-naive surgery patients who filled a prescription claim for an opioid versus those who did not after an inpatient or outpatient surgery. With few exceptions, predicted 1-year post-index total health care costs were significantly higher for surgery patients who received opioids than for their nonopioid counterparts, largely due to differences in medical costs. Opioid users were also more likely to have an inpatient admission or ED visit within 1 year after their surgery. Similar results were noted in the outpatient surgery cohort.

This study analyzed surgery patients who filled a prescription for opioids in the year after surgery versus those who did not. The majority of the patients had an opioid prescription filled in the 7 days before through the 7 days after surgery. In general, opioid users across all 3 payers were younger, more likely to be female, and more likely to be diagnosed with comorbidities versus those who did not receive opioids. These observations are in line with the previous studies that reported increased risk of persistent opioid use/misuse among the younger age group, females, and those with certain preexisting comorbidities (chronic pain, major depression, or those with coexisting psychological comorbidity).15,28,29

Postsurgical Opioid Use Independently Associated with Increased Cost

Postsurgical opioid use imposes a substantial burden on the U.S. health care system, yet there is a lack of evidence quantifying it among surgery patients with persistent opioid use following their surgical procedure. Gold et al. conducted a retrospective analysis (2008-2011) comparing health care utilization and costs among joint replacement surgery patients who received long-acting opioids versus those who did not. They reported that patients who received long-acting opioid prescriptions within 30 days following surgery incurred greater health care costs over 12 months versus those who did not receive long-acting opioids.14

The results of this study support those reported by Gold et al. In this study, previously opioid-naive patients who received an opioid prescription after a major surgical event had significantly higher (19%-61%; P < 0.001) adjusted total health care costs compared with nonopioid users. The higher adjusted 1-year post-index period costs for opioid users versus nonopioid users (all P < 0.001) were primarily driven by medical costs.

Notable strengths that differentiate this study from that of Gold et al. include a sample that is almost 40 times larger (4,105,121 vs. 118,816 patients), use of data from a more contemporary time frame (2010-2016) derived from 3 major U.S. payer sources, and inclusion of patients who underwent surgical procedures in inpatient and outpatient settings across multiple surgery types, including general, obstetric/gynecological, orthopedic, and plastic surgeries. Furthermore, this study looked only at patients who were previously opioidnaive, highlighting the importance of limiting exposure to opioids postsurgery, especially in populations without previous opioid use.

Postsurgical Opioid Use Associated with Poorer Medical Outcomes and Increased Utilization

Previous U.S.-based analyses have shown an association between preoperative chronic opioid use and poor clinical outcomes postsurgery.19,26,30,31 To date, no analyses have been conducted to assess medical outcomes among opioid-naive surgical patients who received prescription opioids compared with those who did not receive opioids for postsurgical pain. In this analysis, negative medical outcomes (i.e., subsequent surgeries within 1 year and postsurgical pain over the 90 days) occurred more frequently after surgery among opioid users than nonopioid users. This suggests that persistent opioid use postsurgery is a modifiable risk factor for poorer medical outcomes.

Similar to patterns found in the health care cost analysis, opioid users had significantly more health care resource utilization (inpatient admissions, ED visits, and pharmacy claims) over the 1-year post-index period than nonopioid users (all P < 0.001). These findings are similar to those by Gold et al., who reported that long-acting opioid recipients were more likely to have a hospitalization and an ED visit during 12-month follow-up period.14

Clinical Implications

This is the first comprehensive study to evaluate health and cost outcomes among opioid-naive surgery patients who received opioids after surgery versus those who did not in real-world clinical practice. Our analysis adds to the body of literature by examining a large cohort of surgery patients across multiple specialties and surgery types from 3 large nationally representative U.S. claims databases.

In addition, this analysis provides contemporary data on medical outcomes and health care utilization and costs among opioid-naive surgery patients who received opioids versus no opioids for persistent postsurgical pain. While postsurgical opioid use is likely warranted in some surgeries, these data suggest that limiting postsurgical opioid use, even in opioidnaive patients, may decrease the burden to patients and multiple U.S. payers and improve clinical outcomes. Future studies are needed to assess whether patient-centered care pathways that eliminate opioid exposures or limit exposure to the most appropriate populations only can reverse these associations and adverse outcomes.

Limitations

Several limitations inherent to retrospective studies should be noted. There is a potential for misclassification of surgeries, covariates, and outcomes as data for this study were derived from administrative claims as opposed to medical records. The MarketScan research databases rely on administrative claims data for clinical detail, which are subject to data coding limitations and data entry error.

Since this study is based on administrative claims data, illicit use of opioids and use of over-the-counter medications cannot be tracked. The presence of a claim for a filled opioid prescription does not indicate whether the medication was actually taken as prescribed. Opioid use during the index hospital admission (inpatient surgeries) or during the surgical procedure (outpatient surgeries) was not available for this study. Because the follow-up period was a year long, it is possible that later opioid prescriptions could be for subsequent surgeries or other acute or chronic pain conditions, rather than the index procedure.

There may be systematic differences between the study cohorts that account for differences found in health care costs and utilization. While differences between the cohorts were controlled for by multivariable regressions, adjustment was limited to those characteristics that were measured from administrative claims. This analysis used a 1-year follow-up period. Patients who died may have had a follow-up period less than 1 year and therefore would have been excluded from the analysis.

Finally, this study was limited to only those individuals with commercial, Medicare, or Medicaid health coverage. Consequently, results of this analysis may not be generalizable to all surgery patients, especially those with other types of coverage and the uninsured.

Conclusions

Filling an outpatient prescription for opioids in the 1 year after inpatient or outpatient surgery was associated with increased health care utilization and costs across all payers. Reducing pain and opioid use after a surgical hospitalization may reduce opioid use in the year after surgery, which could result in lower costs and improved outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support was provided by Santosh Tiwari, PhD, of IBM Watson Health, and funded by Heron Therapeutics.

APPENDIX A. Health Care Utilization and Costs Among Opioid Users Versus Nonopioid Users During 1-Year Post-Index Period for Patients in the Outpatient Surgery Cohort

| Commercial | Medicare | Medicaid | ||||

| Opioids Postsurgery (n = 1,633,722) | No Opioids Postsurgery (n=543,969) | Opioids Postsurgery (n = 282,702) | No Opioids Postsurgery (n=377,186) | Opioids Postsurgery (n =75,454) | No Opioids Postsurgery (n=17,183) | |

| Health care utilization over 1-year post-index period, n (%) | ||||||

| Inpatient admissions | 115,862 (7.1) | 21,648(4.0)a | 60,876(21.5) | 42,860 (11.4)a | 10,578 (14.0) | 1,807 (10.5)a |

| Ambulance/paramedic services | 39,765 (2.4) | 9,041 (1.7)a | 34,114 (12.1) | 32,152 (8.5)a | 9,334 (12.4) | 1,944 (11.3)a |

| ED visits | 315,714 (19.3) | 67,649 (12.4)a | 87,774 (31.1) | 74,125 (19.7)a | 38,317 (50.8) | 4,947 (28.8)a |

| Pharmacy prescriptions | 1,512,372 (92.6) | 423,577 (77.9)a | 278,996 (98.7) | 345,548 (91.6)a | 71,877 (95.3) | 13,523 (78.7)a |

| Health care costs, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Inpatient admissions | ||||||

| Index admission | 549 (5,402) | 289 (4,592)a | 607 (6,339) | 212 (4,206)a | 277 (8,643) | 194 (3,825) |

| 1-year post-index | 2,396 (18,539) | 1,166 (13,563)a | 6,666 (27,592) | 3,125 (20,486)a | 2,661 (18,937) | 2,626 (25,692) |

| Outpatient services | ||||||

| Index admission | 8,742 (9,312) | 4,893 (7,927)a | 6,003 (11,186) | 3,843 (8,893)a | 2,451 (4,300) | 1,896 (3,855)a |

| 1-year post-index | 8,614 (24,401) | 5,909 (18,328)a | 14,535 (37,649) | 9,112 (25,332)a | 5,139 (14,644) | 6,396 (17,278)a |

| Total medical costs | ||||||

| Index admission | 9,291 (10,566) | 5,182 (9,149)a | 6,610 (12,760) | 4,055 (9,834)a | 2,728 (9,622) | 2,090 (5,415)a |

| 1-year post-index | 11,010 (33,405) | 7,075 (24,289)a | 21,202 (51,364) | 12,236 (35,264)a | 7,800 (25,719) | 9,022 (32,167)a |

| Pharmacy prescriptions | ||||||

| Index admission | 17 (120) | 11 (145)a | 16 (132) | 12 (129)a | 16 (154) | 13 (116)a |

| 1-year post-index | 1,844 (6,438) | 1,763 (6,238)a | 3,497 (7,415) | 2,804 (6,294)a | 2,031 (9,046) | 2,446 (7,441)a |

| Total health care costs | ||||||

| Index admission | 9,308 (10,566) | 5,194 (9,148)a | 6,626 (12,760) | 4,067 (9,834)a | 2,744 (9,627) | 2,104 (5,417)a |

| 1-year post-index | 12,854 (34,847) | 8,838 (25,683)a | 24,699 (52,629) | 15,040 (36,332)a | 9,831 (28,720) | 11,467 (34,156)a |

aP < 0.001; all comparisons for opioid vs. no opioid use after surgery.

ED = emergency department; SD = standard deviation.

APPENDIX B. Multivariable-Adjusted Predicted Cost for Opioid Users Versus Nonopioid Users Among Patients in the Outpatient Surgery Cohort

REFERENCES

- 1.Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. J Pain Res. 2017;10:2287-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Academy of Integrative Pain Management . Pain facts & figures. 2018. Available at: http://painsproject.org/resources/policymakers/pain-facts-figures/. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- 3.Málek J, Ševcík P, Bejšovec D, et al. Postoperative Pain Management. 3rd ed. Prague, Czech Republic: Mladá fronta; 2017. Available at: https://www.wfsahq.org/components/com_virtual_library/media/125136f77e1b7daf7565 bd6653026c35-Postoperative-Pain-Management-170518.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- 4.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367(9522):1618-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou R, Gordon DB, de Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Yun L, Wijeysundera DN. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:g1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujii MH, Hodges AC, Russell RL, et al. Post-discharge opioid prescribing and use after common surgical procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):1004-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nooromid MJ, Blay E Jr, Holl JL, et al. Discharge prescription patterns of opioid and nonopioid analgesics after common surgical procedures. Pain Rep. 2018;3(1):e637-e637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Longterm analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(5):425-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in U.S. adults. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(6):e170504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):478-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JS, Hu HM, Edelman AL, et al. New persistent opioid use among patients with cancer after curative-intent surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(36):4042-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang A, Azam A, Segal S, et al. Chronic postsurgical pain and persistent opioid use following surgery: the need for a transitional pain service. Pain Manag. 2016;6(5):435-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gold LS, Strassels SA, Hansen RN. Health care costs and utilization in patients receiving prescriptions for long-acting opioids for acute postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(9):747-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science . Exposing a silent gateway to persistent opioid use - a choices matter status report. 2018. Available at: https://www.planagainstpain.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ChoicesMatter_Report_2018.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- 17.Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(11):1066-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cron DC, Englesbe MJ, Bolton CJ, et al. Preoperative opioid use is independently associated with increased costs and worse outcomes after major abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):695-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen RN, Pham A, Strassels SA, Balaban S, Wan GJ. Comparative analysis of length of stay and inpatient costs for orthopedic surgery patients treated with IV acetaminophen and IV opioids vs. IV opioids alone for postoperative pain. Adv Ther. 2016;33(9):1635-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hansen RN, Pham AT, Lovelace B, Balaban S, Wan GJ. Comparative analysis of inpatient costs for obstetrics and gynecology surgery patients treated with IV acetaminophen and IV opioids versus IV opioid-only analgesia for postoperative pain. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;51(10):834-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler ER, Shah M, Gruschkus SK, Raju A. Cost and quality implications of opioid-based postsurgical pain control using administrative claims data from a large health system: opioid-related adverse events and their impact on clinical and economic outcomes. Pharmacother. 2013;33(4):383-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maiese BA, Pham AT, Shah MV, Eaddy MT, Lunacsek OE, Wan GJ. Hospitalization costs for patients undergoing orthopedic surgery treated with intravenous acetaminophen (IV-APAP) plus other IV analgesics or IV opioid monotherapy for postoperative pain. Adv Ther. 2017;34(2):421-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minkowitz HS, Gruschkus SK, Shah M, Raju A. Adverse drug events among patients receiving postsurgical opioids in a large health system: risk factors and outcomes. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(18):1556-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shafi S, Collinsworth AW, Copeland LA, et al. Association of opioid-related adverse drug events with clinical and cost outcomes among surgical patients in a large integrated health care delivery system. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(8):757-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waljee JF, Cron DC, Steiger RM, Zhong L, Englesbe MJ, Brummett CM. Effect of preoperative opioid exposure on healthcare utilization and expenditures following elective abdominal surgery. Ann Surg. 2017;265(4):715-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project . Procedure classes 2015. 2015. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/procedure/procedure.jsp. Accessed May 28, 2019.

- 28.Helmerhorst GTT, Vranceanu A-M, Vrahas M, Smith M, Ring D. Risk factors for continued opioid use one to two months after surgery for musculoskeletal trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(6):495-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inacio MCS, Hansen C, Pratt NL, Graves SE, Roughead EE. Risk factors for persistent and new chronic opioid use in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain N, Brock JL, Phillips FM, Weaver T, Khan SN. Chronic preoperative opioid use is a risk factor for increased complications, resource use, and costs after cervical fusion. Spine J. 2018;18(11):1989-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain N, Phillips FM, Weaver T, Khan SN. Preoperative chronic opioid therapy: a risk factor for complications, readmission, continued opioid use and increased costs after one- and two-level posterior lumbar fusion. Spine. 2018;43(19):1331-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]