Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Evidence suggests that real-world treatment patterns of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) do not always follow evidence-based treatment recommendations such as those of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, which recommends treatment escalation based on disease progression. This U.S. database study evaluated treatment patterns in patients with COPD, focusing on time to initiation of triple therapy using multiple inhalers.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) estimate time from diagnosis to initiation of long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) monotherapy, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) dual therapy, or LAMA/LABA dual therapy; (b) estimate time to initiation of triple therapy from LAMA monotherapy and ICS/LABA or LAMA/LABA dual therapies; and (c) estimate the likelihood of patient progression to triple therapy.

METHODS:

This study was a retrospective analysis of patients with COPD newly started on LAMA monotherapy, ICS/LABA, or LAMA/LABA therapy between July 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, as identified in Humana’s research database. Patients who were fully insured with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance plans and were aged ≥ 40 years at index with at least 1 hospitalization, 1 emergency department, or 1 medical office visit claim with a COPD diagnosis in the pre-index year were included in the analysis. Time from diagnosis to initiation of index therapy and time to triple therapy after index therapy were assessed. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to estimate the likelihood of progression to triple therapy.

RESULTS:

Of 13,541 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD, 4,000 received LAMA monotherapy; 8,207 received ICS/LABA therapy; and 77 received LAMA/LABA therapy at index; mean time (± SD) from COPD diagnosis to initiation of triple therapy was 178 (± 134) days, 185 (± 130) days, and 252 (± 124) days, respectively. During the study, 28% (n = 1,130) of patients receiving LAMA monotherapy and 20% (n = 1,647) of patients receiving dual therapy (ICS/LABA, n = 1,615; LAMA/LABA, n = 32) progressed to triple therapy. Of the patients who progressed to triple therapy, 63% and 57% of patients receiving monotherapy and dual therapy, respectively, progressed in the 12 months after the index date. In the 12 months before initiation of triple therapy, approximately 50% of patients in the LAMA monotherapy, ICS/LABA, and LAMA/LABA therapy groups had an exacerbation. In the multivariable analysis, discontinuation of therapy, smoking history, and concomitant use of xanthenes and short-acting beta2-agonists were significant predictors of progression from index therapy to triple therapy.

CONCLUSIONS:

Approximately 25% of patients with COPD progressed to triple therapy within 12 months of initiating treatment with monotherapy or dual therapy. Exacerbations were reported in only 50% of these patients, indicating that the other 50% may have escalated to triple therapy for other reasons. Treatment discontinuation, smoking history, the use of a LAMA, and concomitant medication use were significant predictors of progression to triple therapy.

What is already known about this subject

At the time of this study, guidelines for treatment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) suggested step-wise escalation of treatment from monotherapy, to dual therapy, and to triple therapy, depending on the severity of the disease and the risk of exacerbations.

Real-life treatment patterns differ from evidence-based treatment recommendations, and some of the factors affecting treatment pathways have been measured in a few country-specific studies.

What this study adds

Study results showed that significant variation from COPD treatment recommendations for triple therapy is evident.

About 25% of patients with COPD progressed to triple therapy within 1 year of initiation of treatment with monotherapy or dual therapy; however, this progression was not always preceded by an exacerbation.

Some of the predictors of progression to triple therapy were smoking history, treatment discontinuation, race, and medication history.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death in the United States, yet it is often underdiagnosed, resulting in delayed interventions in patients.1-3 The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2018 guidelines recommend monitoring symptoms and exacerbation risks along with spirometry measurements when determining the pharmacologic management of COPD.4 Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs), either alone or in combination with long-acting beta2-agonists (LABAs), are the preferred therapeutic option for maintenance treatment in patients with moderate and stable COPD.4 In patients with moderate to severe stable COPD, prescribing a combination of different classes of COPD medications is recommended over increasing the dosage of a single bronchodilator, since this approach can provide additional benefits while avoiding unwanted side effects from dose-related toxicity (e.g., tachycardia, cardiac rhythm disturbances, or exaggerated somatic tremors for LABAs; dry mouth for LAMAs).4,5 For patients with severe COPD and with high risk of exacerbations, triple therapy with combinations of a LAMA, a LABA, and an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) via multiple inhalers may be beneficial in improving patient outcomes.4,6,7

Although national and international guidelines exist for treatment of COPD,4,8 evidence suggests that treatments prescribed in the real world do not always follow such recommendations.9-11 Therefore, it is important to understand COPD prescribing patterns in the real world to assure payers and prescribers that multiple inhaler therapy is being escalated in a stepwise fashion. In a UK primary care database study, ICS/LABA and ICS/LABA/LAMA treatments were reported to be the most frequently used therapies for patients in GOLD groups A and B (mild to moderate airflow limitation and low risk of exacerbation).10 When treatment augmentation over 24 months was assessed in a second retrospective database study in the United Kingdom, patients receiving LAMA mono-therapy typically progressed directly to triple therapy with the addition of ICS/LABA.12

Although there is some understanding of treatment patterns in UK primary care settings, similar real-life treatment pattern information in U.S. primary care settings is scarce. In this study, using Humana’s research database, which included patients with commercial and Medicare Advantage insurance coverage (Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug [MAPD] plan) from the United States, triple therapy initiation patterns in patients with COPD were assessed. The specific objectives were to measure the average time from COPD diagnosis to the initiation of monotherapy or dual therapy and assess the relationship between time to progression from monotherapy or dual therapy to triple therapy and exacerbations in these patients. Although some patients may progress to triple therapy sooner than others, the progressive nature of COPD makes it likely that all patients will receive triple therapy eventually. Factors that might predict the likelihood of a patient progressing to triple therapy were also analyzed and may be useful for identifying patients who may benefit from earlier intervention with triple therapy.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a retrospective analysis of patients with COPD who initiated LAMA monotherapy or ICS/LABA or LAMA/LABA dual therapies for the first time between July 1, 2010, and March 31, 2013, in Humana’s research database. Patients were required to be followed for at least 12 months before the date at which all patients reached the end of the study. The full study period was January 2009-May 2014. All patients were required to be continuously enrolled for a minimum of 12 months before and after the index date, which was defined as the date of the first observed use of the included monotherapies or dual therapies.

Data Source

Administrative health care claims data were obtained from Humana’s research database. Humana is a U.S.-based health care company that provides medical and pharmacy benefits through MAPD, commercial, and Part D prescription drug plans. Data used from the research database included member enrollment, medical, and pharmacy data. Information from these different sources were linked for each patient using a unique identifier, which was consistent across all files within the database. Data were obtained for the full study time period. The data accessed consisted of records for patients enrolled in fully insured commercial and MAPD plans. Race/ethnicity and low-income subsidy indicator data were only collected and applicable for the Medicare population.

Sample Selection

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes (491.xx [chronic bronchitis], 492.xx [emphysema], and 496.xx [chronic airway obstruction, not elsewhere classified]) were used to identify patients with COPD diagnoses. Patients who were aged ≥ 40 years at index and had at least 1 hospitalization claim, 1 emergency department claim, or 1 medical claim for 1 office visit in the pre-index year, with a diagnosis of COPD in any field, were included. Patients whose claims records indicated use of LAMA, ICS/LABA, or LAMA/LABA in the pre-index period, those who had comorbid respiratory-related conditions, those who switched plan type from commercial to MAPD, or those who were members of groups contractually excluded from research (including self-funded, administrative services-only employer groups) were excluded from the study. Patients who were residents of Puerto Rico were also excluded because of commonwealth legal constraints on the use of residents’ data.

Included Therapies

LAMA monotherapies included in this study were aclidinium, glycopyrronium, glycopyrrolate, and tiotropium. Dual LAMA/LABA therapies included concomitant use of 1 of the preceding LAMA therapies with 1 LABA (formoterol, salmeterol, indacaterol, or olodaterol) as separate inhalers on the same day or overlapping days of supply at the index date. ICS/LABA therapies included were all strengths of fluticasone furoate/vilanterol, mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate, fluticasone propionate/salmeterol, and budesonide/formoterol fumarate. Similarly, triple therapies included 1 of each ICS, LAMA, and LABA from the previous lists as separate inhalers on the same day or overlapping days of supply at the index date. This definition was also used for the assessment of time to triple therapy.

Discontinuation of therapy was assumed to occur when patients did not have a claim for their index medication within 30 days of the end of the reported day supply of the last fill for that index medication. For the purpose of calculating treatment duration, therapeutic substitutions were considered discontinuation of index medication. Changes in dosing frequency or amount (same index medication) did not constitute a discontinuation of treatment.

Outcome Measures

Based on exposure, patients were divided into 3 groups: LAMA monotherapy, LAMA/LABA dual therapy, and ICS/LABA dual therapy. Outcome measures assessed were time (in days) to initiation of index therapies after COPD diagnosis, time (in days) to progression to triple therapy after initiation of index medications, and exacerbation rates 60 days and 12 months before initiation of triple therapy. This 12-month period may have included time before the index date. Exacerbations were defined as any 1 of the following events: hospitalization with a principal discharge diagnosis of COPD, emergency department visit with a primary diagnosis of COPD, or COPD-related physician visit with a primary diagnosis of COPD and receipt of oral corticosteroid or antibiotic prescription within 5 days of a physician office visit. In addition, factors related to the time to ICS/LABA + LAMA triple therapy were assessed.

Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables were summarized using percentages. Statistical tests of significance for differences in these distributions were conducted, with t-tests used for continuous variables, and chi-square tests used for categorical variables. The a priori alpha level for relevant analyses was set at 0.05, and analyses were two tailed, unless otherwise specified. Time to triple therapy was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier curves. In addition, odds ratios were estimated using multivariable logistic regression models with independent predictors to explore the likelihoods of a patient on mono- or dual-therapies before the index date initiating triple therapy in the 12 months after the index date.

Independent predictors that were introduced into the models included gender, age, race/ethnicity, geographic region, population density (e.g., urban or rural), low-income subsidy indicator, household income, dual eligibility, line of business (LOB; classifying the type of payment plan), RxRiskV index,13 disease burden (Deyo Charlson Index),14,15 discontinuation of therapy, concomitant medication use and smoking history. Race/ethnicity data were obtained from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and were only available for Medicare patients. Household income was derived from patient-level financial survey data provided by KBM AmeriLINK. Smoking history or status was defined as a member being a current or previous smoker. The smoker status variable was calculated using a series of ICD-9-CM diagnosis and procedure codes, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and CPT level II codes, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes that indicate current smoker, undergoing smoking cessation counseling or smoking cessation therapy, or a history of smoking. Claims for use of various smoking cessation products were also included in the algorithm. The window for observing these variables was from 12 months before and 12 months following the index date for each patient.

Results

Study Population

Of the 13,541 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COPD, 4,000 initiated LAMA monotherapy; 8,207 initiated ICS/LABA dual therapy; and 77 initiated LAMA/LABA dual therapy at index. Overall, patients were predominantly enrolled in MAPD plans (~95%), with an average (±SD) age of 67.7 (±9.7) years at index; two thirds of patients resided in an urban setting. The baseline demographics were comparable between the mono-therapy and dual therapy cohorts (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Patients with COPD Initiating Treatment with Monotherapy or Dual Therapy

| Monotherapy | Dual Therapy | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICS/LABA | LAMA/LABA | ||||||||

| Commercial (n = 177) | Medicare (n = 3,823) | All (n = 4,000) | Commercial (n = 430) | Medicare (n = 7,777) | All (n = 8,207) | Commercial (n = 2)a | Medicare (n = 75) | All (n = 77) | |

| Patients with COPD, n | 177 | 3,823 | 4,000 | 430 | 7,777 | 8,207 | 2 | 75 | 77 |

| Sex, % | |||||||||

| Female | 52.5 | 54.9 | 54.8 | 62.6 | 57.8 | 58.0 | NRa | 60.0 | 61.0 |

| Male | 47.5 | 45.1 | 45.2 | 37.4 | 42.2 | 42.0 | NRa | 40.0 | 39.0 |

| Age, mean (±SD) years | 58.01 (±7.28) | 70.75 (±7.28) | 70.18 (±8.80) | 56.71 (±8.20) | 70.39 (±8.84) | 69.67 (±9.32) | NRa | 70.56(±7.54) | 70.25(±7.71) |

| Geographic region, % | |||||||||

| Midwest | 35.0 | 23.0 | 23.6 | 30.9 | 19.7 | 20.3 | NRa | 29.3 | 28.6 |

| Northeast | 0.6 | 2.9 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | NRa | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| South | 62.2 | 60.5 | 60.6 | 65.8 | 66.8 | 66.7 | NRa | 57.3 | 58.4 |

| West | 2.3 | 8.9 | 8.6 | 2.3 | 7.6 | 7.3 | NRa | 10.7 | 10.4 |

| Unknown | 0.0 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 4.0 | NRa | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Race/ethnicity (Medicare patients only),b % | |||||||||

| White | NA | 60.5 | 57.8 | NA | 56.9 | 53.9 | NRa | 29.3 | 28.6 |

| Black | NA | 4.4 | 4.3 | NA | 5.6 | 5.3 | NRa | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Hispanic | NA | 0.6 | 0.5 | NA | 1.1 | 1.1 | NRa | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other | NA | 0.7 | 0.7 | NA | 0.9 | 0.9 | NRa | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Unknown | NA | 33.8 | 36.7 | NA | 35.5 | 38.9 | NRa | 69.3 | 70.1 |

| Low income status,b % | NA | 3.7 | 3.7 | NA | NA | 3.7 | NRa | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Dual eligible,b % | NA | 3.9 | 3.9 | NA | 5.4 | 5.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Low income and dual eligible,b % | NA | 6.8 | 6.8 | NA | 6.4 | 6.4 | NRa | 2.7 | 2.7 |

| Current or former smokers,c % | 53.1 | 39.4 | 41.9 | 40.9 | 32.7 | 35.0 | NRa | 26.7 | 27.3 |

| Deyo-Charlson Index, mean (±SD) | 0.98 (±1.50) | 1.55 (±1.71) | 1.52(±1.70) | 0.80 (±1.19) | 1.73 (±1.86) | 1.69 (±1.85) | NRa | 1.64 (±1.38) | 1.63 (±1.38) |

| Time to discontinuation of index Tx, days, mean (±SD) | 176.81 (±121.83) | 211.72 (±100.20) | 209.87 (±101.59) | 200.71 (±102.24) | 212.47 (±107.18) | 211.95 (±106.94) | NRa | 80.00 (±69.31) | 80.00 (±69.31) |

| Time to switch, days, mean (±SD) | 109.94 (±116.91) | 107.85 (±107.37) | 107.97 (±107.86) | 132.49 (±115.17) | 116.23 (±115.88) | 116.98 (±115.87) | NRa | 29.79 (±57.20) | 29.30 (±56.52) |

| Patients progressing to triple therapy,d n (%) | NA | NA | 1,130 (28.0) | NA | NA | 1,615 (20.0) | NA | NA | 32(42.0) |

a To protect patient anonymity, data for populations < 10 patients are not presented.

b Race/ethnicity and low-income subsidy indicator data were only collected for the Medicare population.

c Smoking status was available for 94.0% and 93.9% of patients in the monotherapy and dual therapy groups, respectively.

d Number of patients progressing to triple therapy was assessed only for the overall population, not by plan type.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA = long-acting muscarinic antagonist; NA = not available; NR = not reported; SD = standard deviation; Tx = treatment.

Time to Initiation of Therapies and Treatment Patterns

The mean (±SD) time from COPD diagnosis (defined as first visit during which an ICD-9-CM code for COPD was used) to initiation of therapy was 178 (±134) days in patients starting on LAMA monotherapy, 185 (±130) days in patients starting on ICS/LABA dual therapy, and 252 (±124) days in patients starting on LAMA/LABA dual therapy.

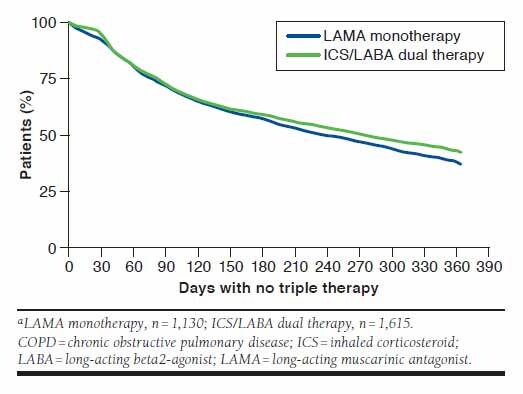

In this study, 28% (n = 1,130) of patients receiving LAMA monotherapy and 20% (n = 1,647) of patients receiving dual therapy (ICS/LABA, n = 1,615; LAMA/LABA, n = 32) progressed to triple therapy (Table 1). Of the patients who progressed to triple therapy from LAMA monotherapy, approximately 63% progressed within 12 months after the index date. Similarly, approximately 57% of the patients who progressed to triple therapy from ICS/LABA dual therapy did so within 12 months after the index date (Figure 1). Results for patients progressing to triple therapy from LAMA/LABA dual therapy are not presented owing to the small number of patients in this group.

FIGURE 1.

Percentages of Patients with COPD Who Did Not Switch to Triple Therapy in the First 12 Months from Index Date of LAMA Monotherapy and ICS/LABA Dual Therapya

Patients receiving LAMA monotherapy progressed to triple therapy after a mean (±SD; median [quartile range]) of 367 (±362; 244 [477]) days and from ICS/LABA to triple therapy after 393 (±366; 281 [533]) days. The time to progression was longer in patients who switched from LAMA/LABA to triple therapy, with a mean (±SD; median) duration of 617 (±454; 514 [894]) days.

Exacerbation Rates

Exacerbation rates were assessed at 60 days and 12 months before initiation of triple therapy. Approximately 20% of patients receiving monotherapy or dual therapy had an exacerbation within the 60 days before initiation of triple therapy; this value was approximately 50% when considering the 12 months before initiation of triple therapy (Table 2). No significant differences in exacerbation rates were observed at 60 days (P = 0.548) or at 12 months (P = 0.606) between patients receiving monotherapy and those receiving ICS/LABA or LAMA/LABA at index (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Patients with COPD Who Experienced an Exacerbation Within 60 Days and 12 Months Before Initiation of Triple Therapy

| N | 60 Days | 12 Months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | P Valuea | n | % | P Valuea | ||

| LAMA | 1,130 | 242 | 21.4 | 0.548 | 533 | 49.0 | 0.606 |

| ICS/LABA | 1,615 | 365 | 22.6 | 821 | 50.8 | ||

| LAMA/LABAb | 32 | <10c | NR | 15 | 46.9 | ||

a P values refer to the comparison of dual therapy (ICS/LABA and LAMA/LABA combined) versus monotherapy (LAMA).

b Because of the small sample size for the LAMA/LABA population, data were not analyzed separately for each dual therapy.

c To protect patient anonymity, data for populations < 10 patients are not presented.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA = long-acting muscarinic antagonist; NR = not reported.

Predictors for Initiation of Triple Therapy

In patients with COPD, race/ethnicity; geographic region; discontinuation of therapy; smoking history; concomitant use of inhaled corticosteroids, xanthines, and short-acting beta2-agonists (SABA); and use of LAMA monotherapy were significant predictors of progression to triple therapy (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Factors that Were Significant and Nonsignificant Predictors of Progression to Triple Therapy from Monotherapy or Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD

| Effect | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race, Medicare patients only (reference = white) | ||||

| Black | 0.70 | 0.54 | 0.90 | 0.006 |

| Hispanic | 2.84 | 1.03 | 9.18 | 0.057 |

| Other race | 0.25 | 0.09 | 0.58 | 0.004 |

| Geographic area (reference = Northeast) | ||||

| Midwest | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.93 | 0.009 |

| South | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 0.023 |

| West | 0.70 | 0.53 | 0.92 | 0.011 |

| Discontinuation of therapy (reference = no discontinuation) | ||||

| Discontinuation | 3.68 | 3.21 | 4.22 | <0.0001 |

| Concomitant medication usea (reference = without medication) | ||||

| ICS | 0.71 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.042 |

| Xanthenes | 1.76 | 1.20 | 2.55 | 0.003 |

| SABA | 1.29 | 1.16 | 1.43 | <0.0001 |

| Smoking statusb (reference = nonsmoker) | ||||

| Current or former smoker | 1.29 | 1.16 | 1.43 | <0.0001 |

| Type of therapy (reference=dual therapyc) | ||||

| LAMA monotherapy | 1.72 | 1.47 | 2.04 | <0.0001 |

| Female (reference = male) | 0.95 | 0.86 | 1.05 | 0.278 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.161 |

| Location (reference = suburban) | ||||

| Urban | 0.95 | 0.85 | 1.07 | 0.418 |

| Rural | 1.01 | 0.85 | 1.20 | 0.891 |

| Low-income subsidy status indicator, Medicare patients only (reference = not low income) | ||||

| Low income | 0.97 | 0.79 | 1.20 | 0.797 |

| Dual eligible, Medicare + Medicaid (reference = not dual eligible) | ||||

| Dual eligible | 0.85 | 0.69 | 1.03 | 0.105 |

| Group (reference = commercial) | ||||

| MAPD plan | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.28 | 0.974 |

| Disease burden | ||||

| Deyo Charlson Index | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.06 | 0.060 |

| Medication use (reference = no medication use) | ||||

| Oral corticosteroids | 1.12 | 0.97 | 1.28 | 0.120 |

| LABA | 1.74 | 0.85 | 3.40 | 0.115 |

| ICS/LABAd | 1.15 | 0.97 | 1.36 | 0.103 |

| Anticholinergics | 1.14 | 0.96 | 1.36 | 0.137 |

| Antibiotics | 0.99 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.924 |

a Concomitant medication use: 14 days before and 14 days after the index date of therapy either monotherapy or dual therapy.

b Smoking: based on medical and pharmacy claims 12 months before and 12 months after the index date of therapy.

c Dual therapy = ICS/LABA + LAMA/LABA combined (owing to the small sample size for the LAMA/LABA population, data were not analyzed separately for each dual therapy).

d Concomitant medication use of ICS/LABA within ±14 days of the index date could have occurred, since some patients may have received both ICS and LABA monotherapy within that period.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICS = inhaled corticosteroids; LABA = long-acting beta2-agonists; LAMA = long-acting muscarinic antagonist;MAPD = Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug; SABA = short-acting beta2-agonist.

Patients who were black and those of other nonwhite race were significantly less likely (odds ratio [OR] = 0.70, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.54-0.90, P = 0.006 and OR = 0.25, 95% CI = 0.09-0.58, P = 0.004, respectively) to progress to triple therapy than were white patients, whereas patients in the Midwest, South, and West were 22%-30% less likely than were patients in the Northeast (OR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.58-0.93, P = 0.009; OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.63-0.97, P = 0.023; and OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.53-0.92, P = 0.011, respectively) to progress to triple therapy.

Patients who discontinued use of their index medication were nearly 4 times more likely to start triple therapy (OR = 3.68, 95% CI = 3.21-4.22, P < 0.0001), and those with a smoking history were 29% more likely (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.16-1.43, P < 0.0001) to initiate triple therapy. Patients who received LAMA monotherapy were 72% more likely to start triple therapy than were those who received dual therapy (ICS/LABA and LAMA/LABA combined; OR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.47-2.04, P < 0.0001). Patients with concomitant use of xanthenes (OR = 1.76, 95% CI = 1.20-2.55, P = 0.003) or SABAs (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.16-1.43, P < 0.0001) were more likely to use triple therapy in the post-index period.

Discussion

In this study, 28% and 20% of patients with COPD progressed to triple therapy from monotherapy or dual therapy (ICS/LABA or LAMA/LABA), respectively. Among patients who progressed to triple therapy, approximately 60% of patients who received LAMA monotherapy or dual therapy with ICS/LABA made the transition within 1 year of initiation of their index therapies. In the year before switching to triple therapy, 50% of patients in each cohort had an exacerbation. Multivariable analysis showed that patients who discontinued index treatment and those with a smoking history were more likely to progress to triple therapy within 1 year of starting index treatment.

In U.S. care settings, information on progression to triple therapy in patients with COPD is limited, and this analysis helps to improve understanding of real-life treatment patterns. Our finding that approximately one quarter of U.S. Medicare patients with COPD progressed to triple therapy during the 12 months after index supports the findings of earlier claims database studies, where similar proportions of patients with COPD progressing to triple therapy were reported in the United Kingdom (32%) and Japan (21%).9,16 In the UK study, 25% of patients who progressed to triple therapy did so within 1 year of COPD diagnosis, and 40% did so within 2 years.9 Compared with the UK study, a greater proportion of patients progressed to triple therapy within 1 year in our study. These results may be in part due to the difference in the way time to initiation was calculated. In the UK study, time to triple therapy was assessed from COPD diagnosis rather than treatment initiation. Our study also found a treatment lag of 178-252 days between COPD diagnosis and initiation of index treatments (LAMA monotherapy, LAMA/LABA dual therapy, and ICS/LABA dual therapy). Overall, our findings support those of previous health care claims database studies in the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States.9,16,17

Treatment patterns and pathways leading to triple therapy are not well understood. In this study, at 12 months after index, more patients receiving ICS/LABA dual therapy continued with their index treatments before switching to triple therapy than did patients receiving LAMA monotherapy (~43% vs. ~37%, respectively). Similarly, Wurst et al. (2014) reported a pattern of more patients on ICS/LABA dual therapy at index continuing with their current treatment at 10-12 months after index than those on LAMA monotherapy (60% vs. 44%).18 Landis et al. (2016) also reported that patients on LAMA monotherapy progressed directly to triple therapy more frequently than those on other therapies.12 They suggested that this observation may be due to the ease of adding ICS/LABA to an existing LAMA monotherapy compared with switching to a new dual therapy. However, Brusselle et al. (2015) reported that progress from ICS/LABA dual therapy to triple therapy (ICS/LAMA/LABA) was the most frequently observed treatment pathway.9 Of note, the number of patients treated with LAMA/LABA dual therapy at index in our study was small, possibly because fixed-dose combinations of the LAMAs/LABAs considered in this study were not approved at the time of the study,19-21 and progression to triple therapy in this subset of patients warrants further investigation in a larger group of patients.

GOLD guidelines (both current and those in use during the period studied) recommend triple therapy with ICS and long-acting bronchodilators in patients who are highly symptomatic and are at high risk of exacerbations.4,23 In this study, only about 50% of patients had an exacerbation in the 12 months before initiation of triple therapy, and about 78% had no exacerbation as defined using our algorithms in the 60 days before triple therapy initiation. A U.S. claims database study by Simeone et al. (2017) showed that a similar proportion (57%) of patients progressed to triple therapy with no observed exacerbations in the 12 months before initiation.17 Progression to triple therapy without an exacerbation history was also reported by Brusselle et al. in a UK-based study in which 20% of patients with no exacerbations at baseline and 26% of patients with 1 exacerbation at baseline progressed from ICS/LABA to triple therapy during the study.9 Therefore, exacerbations, while important, were unlikely to be the sole determinant of progression to triple therapy, considering that the addition of a LAMA to ICS/LABA or ICS/LABA to a LAMA could also occur due to increasing symptoms. While there are codes for dyspnea and other COPD symptoms, they are not well documented in the administrative claims.

Other predictors of progression to triple therapy that may have aided in the early identification and treatment of patients who may have benefited from triple therapy were therefore assessed. In this study, patients who discontinued index medications or had a history of smoking or had concomitant use of xanthenes or a SABA medication were more likely to switch to triple therapy within 12 months after the index date. The use of xanthenes and SABAs could be related to more severe disease or an increased likelihood of having more frequent symptoms.

Socioeconomic factors such as race and location also were predictors for progress to triple therapy in this study. Socioeconomic factors have been shown to affect the development of COPD,22 but its effect on therapy choices is not well understood. In the UK database study, the most common pathway for progression to triple therapy in patients with COPD was use of ICS/LABA.9 However, in this study, the use of LAMA monotherapy compared with ICS/LABA was a more significant factor in progression to triple therapy. Miyazaki et al. (2015) also reported that unsatisfactory improvement in shortness of breath with current therapy was the most common reason for progression to triple therapy.16 It is clear, therefore, that the reasons for progression to triple therapy are varied but appear to be underlined by poor disease control.

Limitations

This study had several limitations, mainly related to the use of claims data. Eligibility criteria required continuous enrollment in a health care plan, meaning that patients who did not maintain membership were excluded; therefore, results may not be generalizable to the wider U.S. population. Claims data are primarily collected for reimbursement for health services and not for research purposes; therefore, miscoding and differences in evaluation of diagnostic criteria may occur at database level or provider level. In addition, coding systems used in claims data are not complete in codifying all conditions or symptoms. For example, exacerbations were not measured directly but rather using proxies, a method commonly used in research studies. The exacerbation algorithm by definition requires a medical intervention, thus, cases where no such care was sought or recorded may result in an underestimation of the exacerbation rate.

The smoking history/status indicator was the result of an algorithm based on claims codes rather than personal history reporting so may have introduced error in the model estimates. Socioeconomic information was only available for the Medicare population, which may have introduced bias. Although pharmacy claims data have been used to assess adherence and compliance based on pharmacy claim fill histories in other studies, it was not possible to ensure that patients had taken the treatments under investigation in this study, nor do these data contain any record of use of medication samples.

Our convenience sample was used as a surrogate for the general U.S. Medicare population. However, our sample was more heavily weighted towards the South and Midwest regions, which may have introduced bias. Furthermore, the analysis did not adjust for the method of identification (hospitalization vs. outpatient visits), which could be used as a proxy for disease severity and influence results. Another limitation was the small number of patients receiving LAMA/LABA dual therapy at the time of this study. Therefore, results from this group need to be interpreted cautiously until further confirmation in a larger population has been performed.

Conclusions

Over half of patients with COPD in this analysis progressed to triple therapy within 1 year of initiation of maintenance mono- or dual COPD therapy. Several factors that predicted progression to triple therapy were identified; these may assist in the identification of patients who may benefit from earlier intervention with triple therapy. However, further real-life studies are needed to determine whether time to triple therapy is associated with patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance (in the form of writing assistance, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, grammatical editing, and referencing) was provided by Rachel Edwards, PhD, and Chrystelle Rasamison at Fishawack Indicia (United Kingdom) and was funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) includes: chronic bronchitis and emphysema. 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/copd.htm. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 2.Mannino DM, Homa DM, Akinbami LJ, Ford ES, Redd SC. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease surveillance—United States, 1971-2000. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(6):1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nacul L, Soljak M, Samarasundera E, et al. COPD in England: a comparison of expected, model-based prevalence and observed prevalence from general practice data. J Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(1):108-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2018. Available at: http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 5.Singh D. New combination bronchodilators for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current evidence and future perspectives. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(5):695-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreira J, Drummond M, Pires N, et al. Optimal treatment sequence in COPD: can a consensus be found? Rev Port Pneumol. 2016;22(1):39-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Shi H, Sun X, et al. Benefits of adding fluticasone propionate/salmeterol to tiotropium in COPD: a meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(5):491-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health Care and Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG101]. June 2010. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/respiratory-conditions/chronic-obstructive-pulmo-nary-disease. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 9.Brusselle G, Price D, Gruffydd-Jones K, et al. The inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UK. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price D, West D, Brusselle G, et al. Management of COPD in the UK primary-care setting: an analysis of real-life prescribing patterns. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:889-904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price D, Miravitlles M, Pavord I, et al. First maintenance therapy for COPD in the UK between 2009 and 2012: a retrospective database analysis. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2016;26:16061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landis SH, Wurst K, Le HV, Bonar K, Punekar YS. Can assessment of disease burden prior to changes in initial COPD maintenance treatment provide insight into remaining unmet needs? a retrospective database study in UK primary care. COPD. 2017;14(1):80-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan KL, Sales AE, Liu CF, et al. Construction and characteristics of the RxRisk-V: a VA-adapted pharmacy-based case-mix instrument. Med Care. 2003;41(6):761-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyazaki M, Nakamura H, Takahashi S, et al. The reasons for triple therapy in stable COPD patients in Japanese clinical practice. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1053-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simeone JC, Luthra R, Kaila S, et al. Initiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the U.S. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:73-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wurst KE, Punekar YS, Shukla A. Treatment evolution after COPD diagnosis in the UK primary care setting. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e105296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stiolto Respimat (tiotropium bromide and olodaterol) inhalation spray, for oral inhalation use. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals. Revised May 2015. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/206756Orig1s000lbl.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 20.Bevespi Aerosphere (glycopyrrolate and formoterol fumarate) inhalation aerosol, for oral inhalation use. AstraZeneca. Revised March 2016. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/208294s000lbl.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 21.Utibron Neohaler (indacaterol and glycopyrrolate) inhalation powder, for oral inhalation use. Novartis. Revised October 2015. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/207930s000lbl.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

- 22.Grigsby M, Siddharthan T, Chowdhury MA, et al. Socioeconomic status and COPD among low- and middle-income countries. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2497-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]