Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Ten biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) are available as treatment for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but relatively little is known about population-level time trends in the use of these agents.

OBJECTIVE:

To describe time trends in the use of bDMARDs in RA patients with private or public insurance in the United States.

METHODS:

Claims data from private (Optum Clinformatics, 2004-2015) and public (Medicaid Analytic eXtract [MAX], 2000-2010) insurance programs were used. Patients with RA diagnosis codes and continuous health plan enrollment for 1-year baseline and 1-year follow-up periods were identified into 2 separate cohorts: (1) patients not using any bDMARD or (2) patients using a single bDMARD during the baseline period. Initiation of the first bDMARD from group 1 and switch to a second bDMARD from group 2 was identified as the outcome of interest during the 1-year follow-up period. Using mixed-effects regression models, we calculated yearly rates of initiation and switch for bDMARDs, adjusted for case-mix. We also described the proportion of all initiations and switches accounted for by each agent.

RESULTS:

There were 113,031 RA patients with public insurance and 97,751 RA patients with private insurance who were included in the study. The rates of initiation of bDMARDs (per 100 patients) increased significantly over time in Medicaid data for incident RA patients (from 1.1 to 3.1, P = 0.0006) and prevalent RA patients (from 4.6 to 10.9, P = 0.008). In Optum Clinformatics data, the rates were stable, with 7.7 to 8.3 per 100 incident RA patients (P = 0.10) and 11.0 to 11.5 per 100 prevalent RA patients (P = 0.12). The rates of switching (per 100 patients) increased over time from 6.4 to 16.0 (P = 0.04) in Medicaid data and 9.1 to 17.0 (P = 0.00003) in Optum Clinformatics data. Use of etanercept as the most common first-line agent was stable at approximately 50% of all biologic initiations, but use of infliximab decreased and the use of newer agents increased.

CONCLUSIONS:

More RA patients used bDMARDs in recent years, and use of newer agents, including certolizumab, golumumab, and tocilizumab, is rising, which highlights a need for further comparative safety and effectiveness research of these agents to better guide evidence-based decision making.

What is already known about this subject

Ten biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) are currently approved for treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA), yet contemporary data on trends in use at the population level are scarce.

The utilization patterns of the more recently approved agents— certolizumab in 2008, golimumab in 2009, tocilizumab in 2010, and tofacitinib in 2012—are not well studied.

What this study adds

In this study, a steady increase was noted in the use of bDMARDs, especially among Medicaid enrolled RA patients, over the 15-year study period (2001-2015).

Etanercept remains the most frequently used agent; however, use of adalimumab and infliximab is decreasing, and the use of newer agents, especially abatacept, golimumab, and certolizumab, has considerably risen in recent years.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which affects approximately 1.3 million adults in the United States,1 is associated with high morbidity and economic burden.2,3 In the last 2 decades, introduction of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs) that target specific components of the immune system involved in the pathogenesis of RA, such as T cells, B cells, and cytokines (i.e., tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-alpha and interleukins), has substantially improved the care of RA patients with high disease activity despite treatment with older nonspecific immunomodulatory agents such as methotrexate or hydroxychloroquine.4 Use of bDMARDs in recent years has contributed to the markedly increased remission rates of RA,5 and sustained remission is known to result in economic benefits to the health care system in the form of reduced use of health services in addition to improved quality of life and patient productivity.6

Currently, there are 10 targeted DMARDs approved for the indication of RA: 5 TNF-alpha inhibitors (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab); 2 interleukin inhibitors (tocilizumab and anakinra); a T-cell activation inhibitor (abatacept); a CD-20 activity blocker (rituximab); and a janus kinase inhibitor (tofacitinib). Nine of the 10 targeted DMARDs indicated for RA are biologics; the only exception is tofacitinib, which is a small molecule-targeted DMARD. According to estimates from an employer-based health insurance claims database up to 2007, 98% of patients with RA who were prescribed a bDMARD received infliximab, etanercept, or adalimumab.7 Similarly, estimates from a nationwide cohort of Medicare patients up to 2009 also indicate predominance of infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab as agents of choice for RA and relatively low use of abatacept and rituximab.8

Because bDMARDs for RA account for a high proportion of specialty drug spending,9 documenting temporal changes in use patterns of these agents is important in order to understand provider and patient preferences for treatment, which may ultimately have implications for managed care in formulary planning, anticipating future need, and cost trajectories. However, contemporary data on trends in the use of bDMARDs after the approval of newer agents, including certolizumab in 2008, golimumab in 2009, tocilizumab in 2010, and tofacitinib in 2012, are unavailable. To that end, we used data from 2 large population-based insurance programs from the United States—Medicaid and Optum Clinformatics—which collectively cover approximately 125 million lives, to conduct a cohort study describing time trends in the use of bDMARDs in RA patients over 15 years.

Methods

Data Source

Patient-level data from commercial health insurance plans (Optum Clinformatics, 2004-2015) and public health insurance plans (Medicaid Analytic eXtract [MAX], 2000-2010) were used for this analysis. Data from enrollees in these 2 programs were available for all 50 states and the District of Columbia, except for Arizona residents in the Medicaid program. These databases contain comprehensive information on patient demographics, inpatient and outpatient medical encounters, and filled prescriptions, which can be tracked longitudinally. Patient consent was not needed, since only de-identified data were used for this study. The use of these de-identified patient data was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Study Cohort

We identified patients aged ≥ 18 years with 2 inpatient or outpatient medical claims with a diagnosis of RA (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code 714.xx) that were ≥ 7 days but < 365 days apart.10 The date of the second claim with an RA diagnosis was defined as the index date, and patients were required to have at least 1-year pre-index and 1-year post-index continuous enrollment in their health plans to ensure comprehensive availability of data on their health care use over this period. The pre-index period of 1 year was used to determine patients’ ongoing use of bDMARDs, and the post-index period of 1 year was used to determine initiation of a new bDMARD or switch to a different bDMARD. We further classified the identified patients into 2 groups based on their bDMARD use in the pre-index period: (1) patients not using any bDMARD and (2) patients using a single bDMARD agent. For this study, we considered infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab, anakinra, abatacept, tocilizumab, rituximab, and tofacitinib as bDMARDs and used pharmacy claims, as well as J-codes, to identify their use. We also excluded patients who used more than 1 bDMARD during the baseline period, since the main focus of this investigation was on describing use of first-line and second-line bDMARD use.

Outcome

The outcome of interest was initiation of treatment with or switch to a new bDMARD. Among patients not using any bDMARDs before the index date, we described time trends in rates of initiation of a new bDMARD stratified by the data source (Medicaid or Optum Clinformatics) and incidence or prevalent RA diagnoses. Prevalent RA was defined as > 1 RA visit or use of non-bDMARDs (methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, cyclosporine, leflunomide, minocycline, sulfasalazine, and gold compounds) in the pre-index period, and incident RA was defined as only 1 RA visit and no DMARD use in the pre-index period. Among patients who were using bDMARDs in the pre-index period, we described time trends in rates of switching to a second bDMARD among commercial and Medicaid patients separately, based on filling a prescription for a different bDMARD than the bDMARD used in the pre-index period.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted the time-trend analyses for initiation and switching separately in the Medicaid and Optum Clinformatics enrollees in 2 steps. First, to account for changing case-mix from year to year, we adjusted for patient-level baseline characteristics in mixed-effect regression models with a logit link and calculated adjusted annual rates in initiation of and switching to a new bDMARD per 100 patients included in our cohort.11 In these models, patient characteristics were modeled as fixed effects, and the year was modeled as a normally distributed random intercept. Patient characteristics included were demographics (age, gender, and region); RA-related medication use (glucocorticoids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opioids, and non-bDMARDs, including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, gold compounds, leflunomide, minocycline, mycophenolate mofetil, penicillamine, and sulfasalazine); a combined comorbidity score including elements from Charlson and Elixhauser scores12; and health care use characteristics, including numbers of office visits, hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and distinct prescription medications used during the 1-year pre-index period.

Second, we tested for linear trends in the adjusted annual rates to report statistical significance of the time trends. Among patients identified as initiating or switching to a new bDMARD, we also described time trends in the use of individual agents as crude proportions. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

We identified 113,031 Medicaid enrollees and 97,751 Optum Clinformatics enrollees with RA for this study. For initiation analysis, 185,652 RA patients were identified (105,368 from Medicaid and 80,014 from Optum Clinformatics), and 25,400 were identified for switching analysis (7,663 from Medicaid and 17,737 from Optum Clinformatics). Overall, 15,620 initiations (6,674 in Medicaid and 8,946 in Optum Clinformatics) and 3,119 switches (921 in Medicaid and 2,198 in Optum Clinformatics) of bDMARDs were identified.

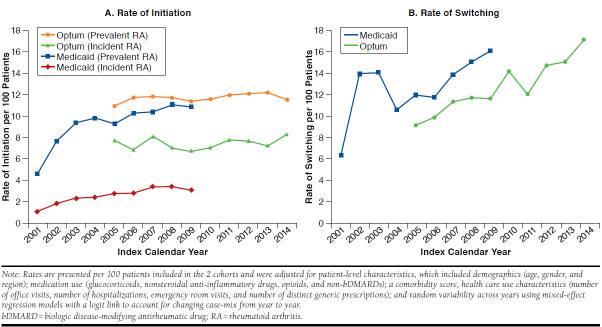

Figure 1 demonstrates the time trends in the rates of initiation and switching in bDMARDs after adjusting for patient case-mix and random variation from year to year over the 12-year study period. The rates of initiation of bDMARDs (per 100 patients) increased significantly over time in the Medicaid patients for incident (from 1.1 to 3.1, P = 0.0006) and prevalent RA (from 4.6 to 10.9, P = 0.008) between 2001 and 2009. In Optum Clinformatics patients, the rates were stable with 7.7 to 8.3 per 100 incident RA patients (P = 0.10) and 11.0 to 11.5 per 100 prevalent RA patients (P = 0.12) between 2005 and 2014. The rates of switching (per 100 patients) increased over time from 6.4 to 16.0 (P = 0.04) in Medicaid patients between 2001 and 2009 and 9.1 to 17.0 (P = 0.00003) in Optum Clinformatics patients between 2005 and 2014.

FIGURE 1.

Time Trends in Rates of Initiation and Switching for bDMARDS in RA Patients, by Disease Stage and Payer

Figure 2 summarizes the crude proportions of the use of individual bDMARDs over the years as first- and second-line treatment choices among patients who were prescribed bDMARDs. Use of etanercept as the most common first-line agent was relatively stable at nearly 50% of all new initiations across the study period; however, use of infliximab decreased substantially with availability of other agents, from 38.1% in 2001 to 9.4% in 2009 in Medicaid patients and from 28.4% in 2005 to 6.8% in 2014 in Optum Clinformatics patients. Use of anakinra, commonly used in the early 2000s, fell to near zero by 2005 in both cohorts. The proportion of patients initiating newer agents (abatacept, rituximab, certolizuamb, golimumab, tocilizumab, or tofacitinib) as the first agent reached a combined proportion of 20.7% in 2014 in Optum Clinformatics patients. Among patients switching to a second bDMARD, use of etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab had a noticeable reduction over the years (from a combined use in 89.2% of patients in 2002 to 58.8% in 2009 in Medicaid and 90.2% in 2005 to 43.4% in 2014 in Optum Clinformatics). We observed an increase in the use of newer agents among patients switching their initial bDMARD to another bDMARD during the study period. In 2014, abatacept, certolizumab, golimumab, tocilizumab, and tofacitinib accounted for 13.2%, 13.8%, 6.9%, 11.9%, and 7.5% of switches, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Time Trends in Proportion of Individual bDMARDs as First-Line and Second-Line Agents in RA Patients

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study of RA patients from public and private health insurance programs, we observed a steady increase in the proportion of patients initiating new bDMARDs, as well as switching between bDMARDs, over the 15-year study period. More importantly, we documented widespread adoption of more recently approved individual bDMARDs, which now account for approximately 1 in 4 new initiations and 2 in 5 switches.

This investigation is the first detailed report documenting rates of use of bDMARDs in a nationwide population of Medicaid enrollees. Our observation of lower absolute rates of bDMARD initiation among patients with no previous use of these agents in Medicaid compared with the equivalent patients in Optum Clinformatics may reflect the possibility of more restrictions to access at a policy level in this program. In an earlier investigation, Fischer et al. (2004) reported that nearly two thirds of the state Medicaid programs had some form of prior authorization policy in place for bDMARDs for RA patients.13 Prior authorization policies are often associated with reduced use of associated medications, which may have been the case for bDMARDs in Medicaid. Although we noted an increasing trend in the use of bDMARDs among Medicaid enrollees in more recent years, further research evaluating the effect of restricted access to these agents on patient outcomes may be helpful in informing future policies.

Our study also extends the available knowledge regarding the trends in use of individual bDMARDs. In their investigation, Zhang et al. (2013) noted that among Medicare enrollees between 2007 and 2009, infliximab was the most commonly used agent.8 In later years of their study period, however, a decreasing trend in infliximab use was observed along with an increasing trend in the use of abatacept.

By documenting practice pattern changes after availability of newer bDMARDs, this study contributes important data to the literature. Our finding of the sustained preference for etanercept as the agent of choice for patients initiating new treatment episodes with bDMARDs over the 15-year study period may reflect the emergence of this agent as the safer treatment option, since it has been repeatedly shown to be associated with fewer adverse events compared with adalimumab and infliximab in numerous meta-analyses.14-16

We further noted that in the Optum Clinformatics database, a large proportion of new initiations and a majority of switches were accounted for by abatacept, rituximab, certolizuamb, golimumab, tocilizumab, or tofacitinib by 2014. Evidence from a small number of comparative randomized controlled trials suggest comparable efficacy of these newer agents to older agents, including infliximab, etanercept, or adalimumab.17-20 However, we recently demonstrated a dearth of comparative safety evidence for these newer bDMARDs in a systematic review.15

The observation of widespread uptake of these agents from this study further highlights the importance of continuing research to guide evidence-based decision making for patients with RA. With the introduction of biosimilars into the market in the near future, closely monitoring patterns, pricing, and outcomes of biologic use in RA would provide important insights.

This study has several notable strengths. It is the largest study currently available in the literature deriving data from more than 200,000 RA patients to describe time trends in the use of bDMARDs. Also, because of comprehensive recording of medical diagnoses and prescription dispensing in the health insurance claims available to us, we were able to account for a large number of potential variables in our analysis that may distort time trends because of the changing case-mix of patients over the study period. This study also includes patients from a broad range of socioeconomic backgrounds from all over the country so, therefore, has high generalizability.

Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. The most important limitation is unavailability of disease activity data, which may have hampered our ability to completely account for the changing patient case-mix over the years. A second limitation is that our data did not contain information on prescriptions that were written but never filled. Therefore, our findings may not completely represent physician practice patterns and should be interpreted as trends in dispensing of bDMARDs.

Conclusions

In this study, a steady increase in use of bDMARDs was noted over the 15-year study period. This increase may be attributable to a greater number of treatment options available, from 3 in 2002 to 10 since 2012, as well as increasing experiences and familiarity of physicians with these agents. Further, we observed that etanercept has remained the most frequently used agent over the past decade in patients initiating bDMARDs for the first time in 2 large U.S. health insurance programs; however, use of adalimumab and infliximab is decreasing, and the use of newer agents, including abatacept, golimumab, tocilizumab, tofacitinib, and certolizumab, has considerably risen in recent years.

REFERENCES

- 1.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):15-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michaud K, Messer J, Choi HK, Wolfe F.. Direct medical costs and their predictors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a three-year study of 7,527 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(10):2750-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper NJ. Economic burden of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000;39(1):28-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donahue K, Jonas D, Hansen R, et al. Drug therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in adults: an update. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 55. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD. April 2012. Available from: https://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/203/1044/CER55_DrugTherapiesforRheumatoidArthritis_FinalReport_20120618.pdf. Accessed June 28, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aga AB, Lie E, Uhlig T, et al. Time trends in disease activity, response and remission rates in rheumatoid arthritis during the past decade: results from the NOR-DMARD study 2000-2010. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):381-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnabe C, Thanh NX, Ohinmaa A, et al. Healthcare service utilisation costs are reduced when rheumatoid arthritis patients achieve sustained remission. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(10):1664-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McBride S, Sarsour K, White LA, Nelson DR, Chawla AJ, Johnston JA.. Biologic disease-modifying drug treatment patterns and associated costs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(10):2141-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Xie F, Delzell E, et al. Trends in the use of biologic agents among rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in the U.S. Medicare program. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65(11):1743-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dusetzina SB. Share of specialty drugs in commercial plans nearly quadrupled, 2003-14. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(7):1241-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SY, Servi A, Polinski JM, et al. Validation of rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses in health care utilization data. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(1):R32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verbeke G, Molenberghs G.. Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data. New York: Springer Verlag; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S.. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischer LM, Schlienger RG, Matter C, Jick H, Meier CR.. Effect of rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus on the risk of first-time acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(2):198-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desai RJ, Hansen RA, Rao JK, et al. Mixed treatment comparison of the treatment discontinuations of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46(11):1491-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desai RJ, Thaler KJ, Mahlknecht P, et al. Comparative risk of harm associated with the use of targeted immunomodulators: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016;68(8):1078-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: a network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(2):CD008794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiff M, Keiserman M, Codding C, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept or infliximab vs placebo in ATTEST: a phase III, multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(8):1096-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleischmann R, Cutolo M, Genovese MC, et al. Phase IIb dose-ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP-690,550) or adalimumab monotherapy versus placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):617-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):508-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schiff M, Weinblatt ME, Valente R, et al. Head-to-head comparison of subcutaneous abatacept versus adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis: two-year efficacy and safety findings from AMPLE trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):86-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]