Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The behavior of medication nonadherence is distinguished into primary and secondary nonadherence. Primary nonadherence (PNA) is not as thoroughly studied as secondary nonadherence.

OBJECTIVE:

To explore and synthesize contributing factors to PNA based on the existing body of literature.

METHODS:

A search was performed on the PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ScienceDirect databases to identify previously published scholarly articles that described the “factors,” “reasons,” “determinants” or “facilitators” of PNA. The alternate spelling of “nonadherence” was used as well. The effect that the articles had in the research community, as well as across social media, was also explored.

RESULTS:

22 studies met the inclusion criteria for this review. The PNA factors that the studies identified were diverse, spanning economic, social, and medical dimensions. A multilevel classification method was applied to categorize the factors into 5 broad groups—patient, medication, health care provider, health care system, and socioeconomic factors. Patient factors were reported the most. Some groups overlapped and shared a dynamic causal relationship where one group influenced the outcome of the other.

CONCLUSIONS:

Like all nonadherence behaviors, PNA is multifaceted with highly varied contributing factors that are closely associated with one another. Given the multidimensional nature of PNA, future intervention studies should focus on the dynamic relationship between these factor groups for more efficient outcomes.

What is already known about this subject

Primary nonadherence (PNA) is a subcategory of medication nonadherence and occurs when a patient fails to initiate treatment by not picking up prescribed medications.

Contributing factors to medication nonadherence are complex and multidimensional and can be broadly classified into 5 categories: patient, medication, health care provider, health care system, and socioeconomic factors.

PNA and its contributing factors are not as widely studied as secondary nonadherence (where a patient does not take medication as prescribed, fails to refill the prescription, or discontinues it altogether).

What this study adds

This study examined contributing factors to PNA through a systematic review, in which all factors were classified using a multilevel approach, and the relationships between each classification were explored and established.

This review incorporated article bibliometrics and altmetrics to provide insight on readership, impact, and outreach in the context of citations and social media.

Results from the review indicate that PNA is receiving more attention within the research community, as well as in social media and the news.

Medication adherence is how patients’ behavior corresponds with the medication regimen prescribed or advised by their health care provider.1 Therefore, medication nonadherence denotes a “passive failure” to follow the recommended prescription and represents a multifaceted problem with widespread consequences on the patient and patient-physician relationship as well as health care plans and the health care system as whole.2 Medication nonadherence is classified into 2 main categories—primary and secondary nonadherence.

According to Adams and Stolpe (2016), primary medication nonadherence occurs when a new medication is issued to patients, but they fail to pick it up or initiate treatment within a stipulated time period.3 On the other hand, secondary medication nonadherence happens when patients do not take their medication as prescribed, do not refill the prescription on time, or discontinue their medication altogether.4,5 In the existing literature, there is little research on primary medication nonadherence (PNA), with most works focusing on secondary nonadherence. One main reason lies in the difficulty of capturing PNA, where measurement is contingent on prescription and dispensing information that is typically stored in different databases.6 However, neglecting PNA in the study of medication nonadherence leads to underestimating the overall nonadherence rate, as secondary nonadherence alone does not account for patients who do not pick up new medications.7 In addition, from a clinical standpoint, a patient who fails to initiate treatment poses a different problem from the patient who does so but falls short only at a later point.8 As such, it is important to gain greater insight into the rates and determinants of PNA in the study of medication nonadherence.

As posited by Dalvi and Mekoth (2017), there is no single factor for medication nonadherence.9 Factors informing PNA behaviors are a complex web of interactive causes spanning the economic, social, and medical dimensions, including patients’ attitudes toward taking medication. Miller et al. (1997) broadly categorize nonadherence behaviors into patient factors, medication factors, health care provider factors, health care system factors, and socioeconomic factors.10 This categorization represents a multilevel and multidisciplinary approach that is critical in devising “suitable and individualized solutions” to improve adherence among patients, especially those with chronic conditions.1 As discussed, PNA has not been extensively studied, with few works that explore the contributing factors behind it. Given this background, a systematic review was therefore carried out to investigate the barriers to primary medication adherence worldwide.

Methods

Selection Process

This systematic review was conducted and reported using the PRISMA Statement. A literature search was performed on the PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ScienceDirect databases to identify articles containing information on factors of PNA. The search was limited to English-language publications, covering the time period before March 2017 and excluding letters, editorials, and book chapters. Keywords were primary nonadherence, primary nonadherence, and primary medication adherence. As the topic of PNA has not been widely studied, associated keywords for factors were excluded to yield a larger pool of literature for the first-round search.

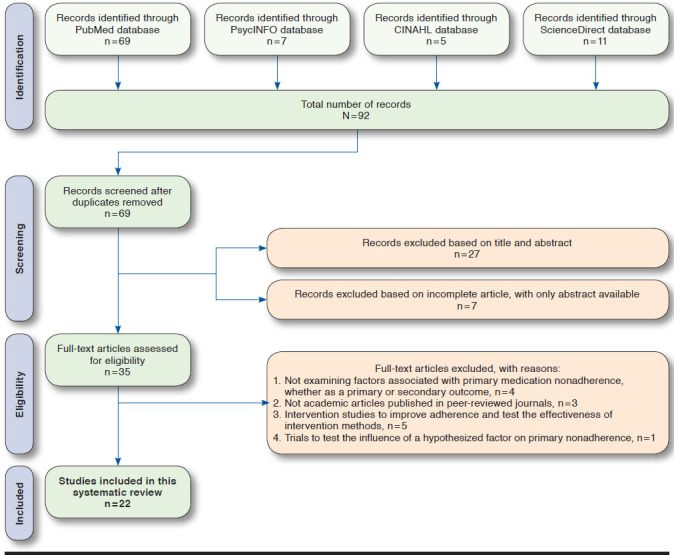

A flowchart of the literature search is presented in Figure 1. The first round identified 92 articles. After removing duplicates, 69 articles were further screened based on their titles and abstracts to determine their eligibility. Studies that cover both primary and secondary nonadherence were included, while those that only explore the general subject of nonadherence without differentiating primary and secondary were excluded.

FIGURE 1.

Literature Search Flowchart

The remaining 35 articles were then reviewed in detail in the second round of selection. Articles that examined “factors,” “reasons,” “determinants,” or “facilitators” of PNA were retained, while those focusing only on rates or intervention methods were omitted. Articles were included in this review if (a) a dosing regimen for any medication was evaluated and PNA reported; (b) specific factors associated with PNA were identified and explored, either as a primary or secondary outcome of the study; (c) they were not interventions designed to improve adherence or test the effectiveness of intervention methods, or trials implemented to study the influence of a certain hypothesized factor; and (d) they described the study design and specified the measurement method and definition of PNA. Therefore, 22 scholarly articles met the final eligibility criteria and formed the basis of this systematic review.

Metric Analysis

We also analyzed the bibliometric and altmetric outreach of the articles with the aim of understanding the outreach and impact they have on research and society.

Bibliometrics are traditional, well-known impact indicators such as citation count, journal impact factor, or h-index.11 In the last few years, research has been increasingly disseminated and discussed on social media. Altmetrics refer to new or alternative metrics aimed at measuring the impact of research.12 Popular examples of altmetrics include tweet count on Twitter, Facebook post count, and Wikipedia mention count. Altmetrics offer a faster and real-time measure of impact when compared with bibliometrics. For instance, if a research article is mentioned across multiple tweets or discussed in Wikipedia pages and blog articles, this provides an indication of the topic’s popularity across social media. Such instances also reflect the impact of research on a wider audience, moving beyond the research community. Hence, the reach and popular appeal of research articles can be ascertained by analyzing the almetric scores. However, altmetrics still face many data quality issues and are easier to manipulate when compared with traditional bibliometrics.13

On May 8, 2017, we collected tweet count, Mendeley readers count, and the Altmetric Attention Score from Altmetric. com, usage and capture data from PlumX, and citation count from Scopus for the articles in the review. Altmetrics are based mainly on social media data sources. The Altmetric Attention Score is an aggregate weighted metric based on data sources such as news outlets, policy documents, blogs, Wikipedia, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. PlumX provides usage data that comprise counts from article downloads, article views, library holdings, video plays, clicks, collaborators, and others. It also offers capture data that consist of counts from bookmarks, favorites, followers, readers, subscribers, viewers, exports, saves, and code forks. To identify citations from prestigious universities, we used the 2015 Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) university rankings. Therefore, the citations extracted from Scopus were classified either as QS or non-QS. The data visualizations are based on a logarithmic scale. Through this metric analysis, our intention is to provide additional insight on the readership, impact, popularity, and attention of PNA in the context of citations and social media networks. We believe that a review article with such metric data would help readers understand prior studies in a different perspective. For instance, further exploration of cited articles and articles shared on social media could provide cues on future research agendas and help readers to frame research questions.

Results

Twenty-two articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in this systematic review. Details such as country of study, participant profile, methods used to assess adherence, and all associated factors of reported nonadherence are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Studies Included in Systematic Review

| Source | Country | Participant Profile | How Adherence Is Assessed | Main Factors Addressed for Primary Nonadherence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Sample Size | Sample Description | Patient Factors | Medication Factors | Health Care Provider Factors | Health Care System Factors | Socioeconomic Factors | |||

| Adamson et al. (2017)14 | United States | 2,496 | New dermatology patients with 1 or more medications prescribed | Electronic medical records and pharmacy claims records | Higher PNA among younger patients Age factor differs in men and women |

Number of dispensed drug (polypharmacy) Cost, especially for elderly patients |

– | Method of prescription (electronic prescription vs. paper prescription) Infrastructure to accommodate the needs of non-English-speaking patients |

– |

| Bauer et al. (2013)22 | United States | 1,366 | Adults aged 30-75 years with type 2 diabetes who were prescribed a new antidepressant during 2006-2010 | Pharmacy claims records | Health literacy and race/ethnicity | – | – | – | Patients with health literacy limitations have poorer adherence |

| Cheetham et al. (2013)15 | United States | 19,826 | Patients aged ≥ 24 years with a new statin prescription (having no statin prescriptions in the previous 12 months) in a large integrated health care delivery system | Electronic medical records | Younger and healthier patients, with fewer comorbid conditions, lower rates of hospitalization, fewer clinic and emergency department visits in previous year | Fewer concurrent prescriptions | – | – | – |

| da Costa et al. (2015)20 | Portugal | 375 | Patients aged ≥ 15 years with chronic medical conditions and a prescription of at least 1 drug for diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia | Questionnaire study and data of medication collection from pharmacist | Higher nonadherence among women for antidiabetic medication | Availability of medication at home Higher nonadherence among women for antidiabetic medication |

– | – | Financial problems faced by patients |

| Fallis et al. (2013)33 | Canada | 232 | Patients aged ≥ 66 years, discharged from the general internal medicine service of a hospital | Claims data in Drug Profile Viewer | – | – | More likely among patients discharged to nursing homes | – | – |

| Harrison et al. (2013)28 | United States | 98 | Patients aged ≥ 24 years, with no record of redeeming a new statin medication within 1 to 2 weeks of being ordered | Phone interview data; self-reported nonadherence | Concerns about taking the medication Patients’ preference for lifestyle modification (e.g., diet and exercise) instead of taking medication Fear of side effects Patients’ perceived redundancy and ineffectiveness of medication |

– | Lack of communication between patient and physician | Financial hardships Inadequate health literacy |

|

| Jackevicius et al. (2008)19 | Canada | 4,591 | Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients aged ≥ 66 years, enrolled in the Enhanced Feedback for Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT) study registry |

The EFFECT study registry and the AMI charts it collects from 104 acute care hospitals in Ontario | Patients’ perceived ineffectiveness and redundancy of medication Older patients |

Patients with more pre-AMI/baseline prescriptions | Patients who do not receive medication counseling and education after discharge Patients who do not have a cardiologist as the most responsible physician |

– | – |

| Jackson et al. (2014)16 | United States | 29,238 | Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years, with a new electronic prescription for medications intended to treat chronic conditions, as supplied by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance (PQA) | Prescription data from 100 retail pharmacies | Slightly younger in age: 59.42 vs. 59.60 years | PQA-defined drug class (e.g., high nonadherence is observed for antiretrovirals) Higher out-of-pocket costs for medication Prescriptions accompanied by another prescription on the same day |

Higher nonadherence when prescriber is neither a physician (both specialist and primary care), physician assistant, or advanced practice nurse Nonadherence more likely to occur in pharmacies with lower prescription volumes |

– | Higher nonadherence when prescriptions originate in pharmacies located in neighborhoods with higher household incomes and educational levels |

| Karter et al. (2010)29 | United States | 169 | Patients with type 2 diabetes receiving a new electronic prescription for insulin—those who are primary adherent and primary nonadherent | Data from computer-assisted interviews and self-administered mailed surveys | Patients’ decision to improve other health behaviors instead of insulin-taking Patients’ perceived negative impact on social and work life Injection phobia Concerns about side effects |

– | Lack of provider-patient communication and explanation of the potential risks and benefits associated with insulin Inadequate shared decision making between provider and patient Lack of insulin self-treatment training for patients |

– | – |

| Polinski et al. (2014)25 | United States | 26 | Patients aged ≥ 25 years with PNA for anti-hypertensive medications | Focus group discussions | Patients’ misperception about medication Fear of side effects Patients’ distrust of health care provider Suspicion of provider’s diagnosis and motivation to prescribe |

Cost Complexity of medication regimen (polypharmacy) |

Poor communication between physician and patient | – | – |

| Pottegård et al. (2014)8 | Denmark | 146,959 | Patients aged ≥ 18 years with free and direct access to general practitioners | Pharmacy records and prescription registry data | Female Younger patients aged 18-29 years Patients with a diagnosis of ischemic heart disease are less adherent Patients with a diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are more adherent |

Polypharmacy | – | – | Highest PNA among patients who earn < 250,000 Danish krone per year |

| Raebel et al. (2011)7 | United States | 12,061 | Members of an integrated health delivery system, with a newly initiated order for an antihypertensive, antidiabetic, or anti-hyperlipidemic medication | Electronic health records within an integrated system | – | PNA varied by therapeutic class—highest among those who ordered antihyperlipidemic medications and lowest among those who ordered anti-hypertensive medications | PNA lower for antihyperlipidemic medications prescribed by a provider in a nonprimary care department | – | – |

| Rashid et al. (2017)17 | United States | 9,050 | Patients aged ≥ 18 years with new overactive bladder prescriptions | Electronic medical records | Female Younger patients aged 56.9 years on average, compared with the overall average age of 62.6 years Patients who have fewer comorbid conditions (i.e., generally healthier otherwise) Race other than white |

Patients who have fewer concomitant medications and prescriptions dispensed in the past year | – | Patients who have commercial insurance compared with those with Medicaid and Medicare | – |

| Reynolds et al. (2013)30 | United States | 8,454 | Women aged ≥ 55 years with a new prescription of oral bisphosphonates | Electronic medical records | Older women with prior emergency department visits Patients’ perceived need for and benefits and risks associated with medication |

– | Prescriptions written by providers with 10 or more years of experience more likely to be redeemed | – | – |

| Shin et al. (2012)5 | United States | 569,095 new prescriptions (398,025 patients) | New prescriptions written for 10 therapeutic drug groups in a 3-month period | Electronic medical records | Black and Hispanic patients Patients naive to therapy and treatment Patients with baseline comorbidities Patients who redeem at least 1 prescription in the previous year or had a prescription for symptomatic disease Younger patients more likely to fill acute medication; less likely for chronic medication |

Types of drug group Regimen complexity Cost of medication (only when disease is acute) |

– | – | – |

| Storm et al. (2008)21 | Denmark | 322 | Outpatients of a public hospital dermatology department, who receive a prescription for an initial treatment with a previously untried medication | Electronic pharmacy register | Patients with chronic diseases (e.g, eczema) less adherent than patients with short-term diseases (e.g., infections) Men more adherent than women Elderly patients the most adherent Patients with topical treatment (compared with those with systemic treatmenta) less adherent |

– | Better adherence among patients who see specialists rather than junior physicians | – | – |

| Thengilsdóttir et al. (2015)6 | Iceland | 10,685 | Adult patients aged ≥ 18 years from the capital area in Iceland who received a new statin or antidepressant prescription within the study period | Prescription database records | Vulnerable groups of patients with disabilities prescribed expensive drugs Women and younger patients |

Patients prescribed SNRIs and atorvastatin compared with those prescribed SSRIs and simvastatin | – | – | – |

| Wamala et al. (2007)31 | Sweden | 31,895 | Patients aged 21-84 years who corresponded with a physician at a hospital or primary care center within a 3-month period | Self-reported nonadherence using postal self-administered questionnaire | – | – | – | Sweden’s “care on equal terms” health policies (publicly funded health care system and subsidized medication) less successful among socio-economically disadvantaged elderly patients | Patients placed lower on the socioeconomic index, especially elderly women |

| Williams et al. (2007)23 | United States | 1,064 | Asthma patients aged 5-56 years, with at least 1 electronic prescription for inhaled corticosteroids and at least 3 months follow-up after the prescription | Electronic prescription information and pharmacy fill data | Low baseline rescue medication use Lower perceived need for medication Race and ethnicity |

– | Frequency of contact between patient and physician, especially for African American patients | – | – |

| Wooldridge et al. (2016)24 | United States | 341 | Adult patients who were hospitalized for cardiovascular events, had new discharge prescriptions to fill post-discharge, and had received study intervention about filling discharge prescriptions | Secondary analysis of data from a randomized, controlled trial evaluating the effect of tailored intervention in adults hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes or acute decompensated heart failure | Single marital status | Polypharmacy (having more than 10 total discharge medications) | Not applicable as patients have undergone tailored intervention of pharmacy-assisted medication reconciliation, discharge counseling, low-literacy adherence aids, and follow-up phone calls | – | Low income: inability to afford medication cost and also faced transportation limitations |

| Wroth et al. (2006)18 | United States | 3,926 | Adult aged ≥ 18 years, having lived in the southeastern rural community for more than 1 year, and visited a health care provider in the previous year | Phone survey data; self-reported non-adherence | Patients aged < 65 years African American Patients with transportation problems Trust and confidence in patient-physician relationship Patients’ satisfaction with care provided |

– | Trust and confidence in patient-physician relationship Patients’ satisfaction with care provided Patient-physician concordance on medication |

– | Annual income of < $25,000 |

| Yu et al. (2015)26 | United States | 430 | Women aged ≥ 55 years with an untreated osteoporosis diagnosis (i.e., no claims for osteoporosis-specific medication) | Mail survey data | Concern over side effects of medication Patients’ beliefs about osteoporosis and osteoporosis medication |

– | – | Cost of medication: contribution of insurance to medication costs | – |

aUsing substances that travel through the bloodstream, reaching and affecting cells all over the body.

PNA = primary nonadherence; SNRI = serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Factors of medication nonadherence, both primary and secondary, are complex and multifaceted. All 22 articles in this review addressed a range of reasons for PNA, covering factors across the economic, social, and medical spectrums. We further organized these reasons according to the multilevel classification system recommended by Miller et al. as shown in Table 1.10 Each article addresses at least 1 of the classified factors, as elaborated in the following brief descriptions.

Patient Factors

Of the 22 articles included in this systematic review, 19 addressed patient factors. These factors encompassed demographics, beliefs/perceptions/attitudes, physical and mental health conditions, medical history, and others. We found that patients’ perceptions toward the effectiveness, risks, and necessity of their prescribed medication constituted a predominant reason for PNA. In some articles, this was associated with health care provider factors, which will be elaborated in the following subsection.

Demographics that were found to affect primary medication adherence varied from study to study. For example, though most studies found younger patients to be more nonadherent compared with older ones,6,8,14-18 Jackevicius et al. (2008) noted the reverse in acute myocardial infarction patients aged 66 and above.19 Women were also consistently found to be more nonadherent compared with men.6,8,17,20,21 In terms of race/ethnicity, it was largely observed that minority groups in the United States, like Hispanic and African American patients, exhibited higher PNA compared with white patients.5,17,18,22,23 One exception was a study of new dermatology patients by Adamson et al. (2017), where Hispanic patients were found to be the most adherent.14

Patient health literacy was also directly associated with PNA, where poor health literacy or health literacy limitations yielded higher PNA among patients.22 However, a few articles attributed health literacy to health care provider factor, which will be expounded in further detail.

Medication Factors

Many articles reported that drug regimen constituted a main determinant of PNA, where polypharmacy and complex dosing regimen were identified as the predominant factors. PNA was higher when there were more baseline medications or drugs prescribed concurrently.14-16,19,24 In some cases, the complexity of one’s overall medication regimen also further acts as a deterrent to adherence.5,25 However, Rashid et al. (2017) found that the reverse of polypharmacy applied to a group of patients with overactive bladder prescriptions, where nonadherent patients were those with fewer concomitant medications.17

High cost of medication was also identified as a contributor to PNA.5,14,16,26 Drug types were found to influence PNA as well, notably in comparative cases where different drug types were studied.5,6,16,20,27 For instance, in a study of Portuguese patients with chronic medical conditions, those prescribed antidiabetic drugs were less adherent compared with those given antihypertensive or antihyperlipidemic drugs.20 Another medication factor in PNA was related to drug handling, where patients commonly cited having leftover medications at home as a reason to be nonadherent. Da Costa et al. (2015) said this could be attributed to medication sharing, medication saving, skipping doses, or different sizes of medication packaging.20

Health Care Provider Factors

Health care provider factors include patient-physician relationship (communication, trust, shared decision making), counseling and education, as well as the experience and credibility of health care providers. In most cases, PNA was attributed to a lack of communication between the patient and physician.18,23,25,28,29 For instance, Polinski et al. (2014) found that poor patient-physician communication caused patients’ distrust in the health care provider and suspicion in the provider’s diagnosis and motivation to prescribe.25 Wroth and Pathman (2006) similarly noted that when patients were made to feel cared for, welcome, and comfortable by the health care provider (physician, nurse, office staff), they were more likely to fill prescriptions.18

Most studies also discovered a strong relationship between PNA and the experience or credibility of the patient’s health care provider. Storm et al. (2008), in their study of Danish outpatients in a public hospital dermatology department, documented better adherence among patients who saw specialists compared with junior physicians.21 In terms of experience, prescriptions that were written by providers with 10 or more years of experience were more likely to be filled.30 However, Jackson et al. (2014) noted the reverse where PNA was higher among patients receiving prescriptions from primary care physicians relative to physician assistants and advanced practice nurses.16

Health Care System Factors

Four out of the 22 articles included in this review addressed health care system factors in the assessment of PNA. On a national policy level, Wamala et al. (2007) found that Sweden’s National Public Health Policy, though implemented to promote equal access to health care, has been less successful among socioeconomically disadvantaged elderly patients.31 Despite having subsidized and even free prescribed medication, PNA was still associated with socioeconomic disadvantage—with threefold increased odds among elderly men and a 6-fold increase among women aged 65-84 years. On a health care facility level, Adamson et al. noted an overall decrease in PNA (47% reduction) with electronic prescriptions as compared with paper prescriptions at a hospital outpatient dermatology clinic, though it was also found that patients with paper prescriptions showed higher adherence during the first 4 days after their index visit.14 In addition, the hospital’s infrastructure to accommodate Spanish-speaking patients contributed to a higher rate of adherence among its Hispanic patients—an anomaly to the trend in other articles where they exhibited higher PNA compared with white patients.

Socioeconomic Factors

Financial hardship and income level were largely identified as barriers to primary medication adherence.8,18,20,24,28,31 In some studies, financial problems were also directly associated and overlapped with patient and medication factors. For instance, not only was PNA higher among patients placed lower on the socioeconomic index, it was also more significant in elderly women31 and in elderly patients who had difficulty affording a high cost of medication.14 Wooldridge et al. (2016) said patients with low earnings also faced transportation limitations, which made it challenging for them to commute to the pharmacy to fill prescriptions after discharge.24 In contrast to these prevailing findings, Jackson et al. observed higher PNA when prescriptions originated in pharmacies located in neighborhoods with higher household incomes and educational levels.16

Metric Analysis

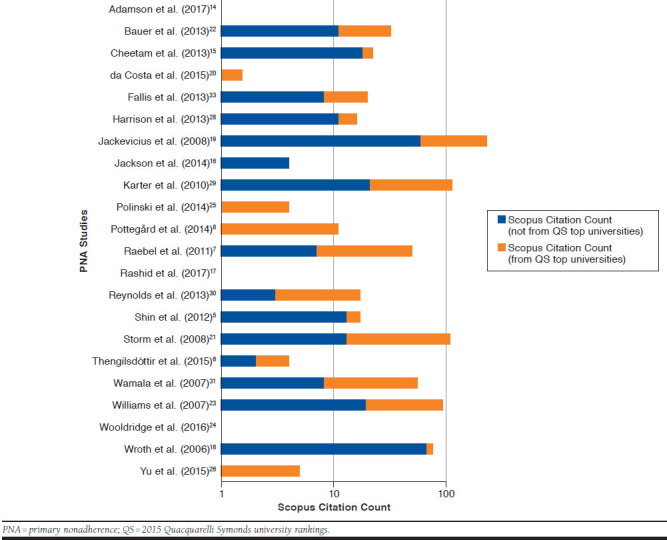

Figure 2 shows the bibliometric outreach of the studies on PNA. The study from Jackevicius et al. had the most citations, with a total of 230, 171 of which were from QS top universities.19 Storm et al. and Karter et al. (2010) also received a large number of citations, with 111 (90 QS) and 107 (94 QS), respectively.21,29 Most of these citations were from the field of medicine.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of the Bibliometric Outreach of PNA Studies

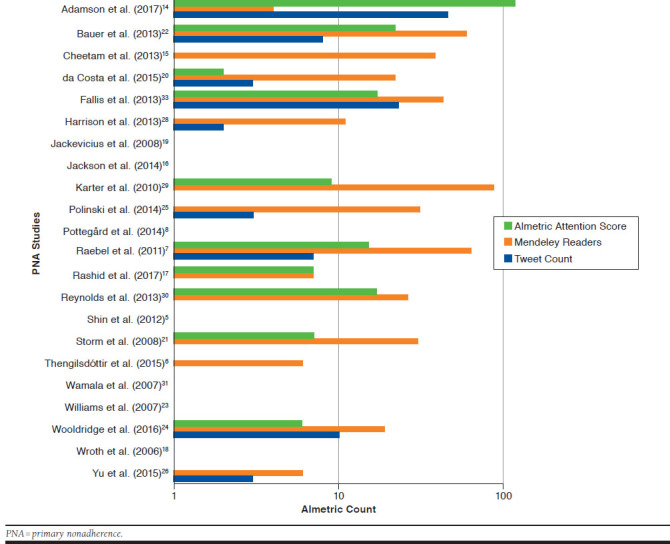

Although some newer studies such as Adamson et al., Rashid et al., and Wooldridge et al. did not have citations,14,17,24 they had an altmetrics presence, as illustrated in Figure 3. The study by Adamson et al. had the highest Altmetric Attention Score of 117, despite only being published recently.14 With this surprisingly high score, it belonged in the top 5% of all research outputs scored by Altmetric.com and had a high attention score (86th percentile) compared with outputs of the same age and source (according to the contextual information provided by Altmetric.com). This can be attributed to the 13 news stories found on 12 news outlets about this study, which included an interview with the study’s first author on the MedicalResearch.com blog.32 The study also received attention on Twitter, with 46 tweets from 31 users. This highlights the advantage of altmetrics as a quick and timely measurement of the outreach and impact of newly published works.

FIGURE 3.

Overview of the Altmetric Outreach of PNA Studies

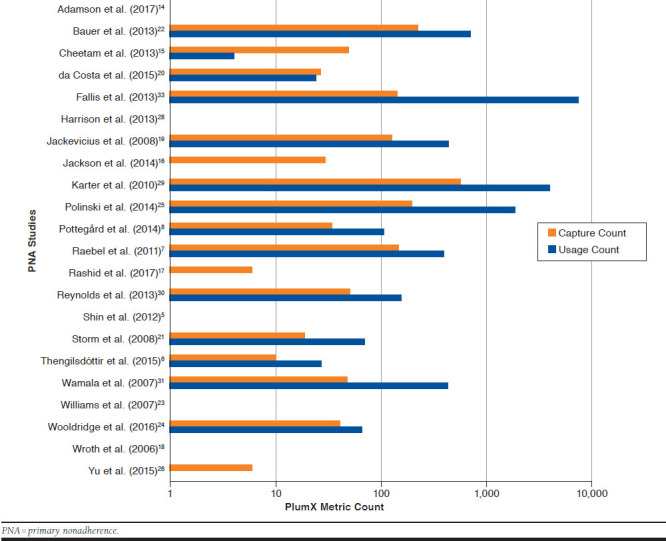

Figure 4 shows the PlumX Usage and Capture metrics for the studies on PNA. Fallis et al. (2013) registered a high usage count of 7,578, which was attributed to HTML and PDF views on PLoS, PubMedCentral, and EBSCO.33 Polinski et al. and Karter et al. also received high usage counts of 1,880 and 3,920, respectively.25,29 Adamson et al. had only 1 usage count.14 Capture count should be considered more important than usage count, as usage can be easily increased if the authors publicize the article extensively on social media and direct researchers to click on the shared URL to view the abstract or full text. However, capture count cannot be easily garnered, as researchers need to have had enough interest in an article to bookmark, favorite, or export it, for example.

FIGURE 4.

Overview of the PlumX Usage and Capture Counts for PNA Studies

Discussion

Adherence to therapy is fundamental to patient care and constitutes an indispensable process in achieving desired clinical outcomes. Nonadherence can result in poor health outcomes and higher overall health care expenditure.34 In the research of medication adherence, extensive literature exists on secondary nonadherence, while PNA has been largely overlooked until recently. Newly developed technology, such as electronic prescribing and electronic medical records, has paved the way for more rigorous, comprehensive, and in-depth study of PNA. PNA is as important to research as secondary nonadherence, and may even be considered more critical as patients fail to initiate treatment by not filling their prescriptions. Furthermore, if a patient fails to possess medication from the beginning, subsequent efforts to improve secondary nonadherence will be futile.

This review classified PNA factors into 5 categories using a previously published approach—patient factors, medication factors, health care provider factors, health care system factors, and socioeconomic factors. Patient factors remained the most highly covered (n = 19), addressing a wide range of components such as demographics, beliefs/perceptions/attitudes, health literacy, and medical history. While variables such as demographics (age, sex, and race) and medical history are definitive and unchangeable, other patient-related characteristics are potentially modifiable. For instance, a number of articles reported that PNA was largely motivated by patients’ perceptions toward the effectiveness, risks, and necessity of their prescribed medication. This represents a modifiable factor, which can be alleviated through various intervention methods that address the root causes of these views. One predominant root cause repeatedly raised in the review is the lack of communication between patient and physician (also classified as a health care provider factor), which contributed significantly to patients filling their medication or cultivated distrust and suspicion in their health care provider.19,25,28,29 In this case, interventions like medication counseling or education for patients and closer collaboration between patient and physician can bridge the communication gap and improve primary medication adherence.

Another recurring group of factors in this review of PNA barriers is the health care provider factor (n = 10), such as poor patient-physician communication, lack of shared decision making between provider and patient, and the disparity between consulting a specialist and nonspecialist as the main physician. In fact, this review observed that many determinants grouped under the category of health care provider factor overlap or share a causal relationship with the patient factors, where one precedes or gives rise to the other. As previously shown, patients’ negative perceptions toward a particular drug (patient factor) is largely informed by a lack of communication between them and their physician (health care provider factor). Similarly, inadequate shared decision making between the patient and physician on what medication to prescribe (health care provider factor) also potentially breeds patients’ distrust and suspicion in the provider’s diagnosis and motivation to prescribe (patient factor), and eventually discourages primary medication adherence. This demonstrates that reasons for PNA, though distinguished in neat categories, are rarely stand-alone causes independent of one another. Instead, they are dynamic and interactive factors, closely associated with each other in a web of interconnectedness. Therefore, given this multidimensional nature of PNA, it is imperative that any solution or intervention method devised is predicated on a comprehensive understanding of the complexity of nonadherence behavior.

While many factors are unchangeable (such as demographics, medical history, and patients’ socioeconomic status) or difficult to overcome in the short term due to their large-scale nature (such as the characteristics and operations of a health care system or the cost of medication), some reasons addressed in this review are more fluid and open to intervention at a smaller level. These include polypharmacy, patients’ views on taking medication, health literacy, patient-physician relationship, and many others. In the existing literature on PNA, there are a number of intervention studies on ways to improve primary medication adherence. A majority of these studies seek to address patients’ concerns about medication effect, as well as their lack of information and knowledge about prescribed therapy and its associated benefits, via intervention methods such as voice response phone calls, follow-up letters, and post-discharge pharmacist counseling.4,35-37 Most studies reported a positive effect in lowering the rate of PNA. However, there is no known intervention study on other potentially modifiable PNA barriers such as polypharmacy and patient-physician relationship. Future studies could focus on addressing these factors in improving primary medication adherence.

Through our bibliometric and altmetric analysis, we found that 86% of the articles included in this review had citation counts, while 64% received attention on social media. This finding provides a clear indication that studies on PNA continue to receive a fair amount of attention from the research community, as well as on social media and in the news. This finding also presents an optimistic sign that research on PNA, long sidelined in the study of medication nonadherence, is beginning to gain more importance in recent years. Its increasing presence on social media and online news also signifies a growing awareness of the issue. This might introduce new perspectives to the costly phenomenon of medication nonadherence, and subsequently, initiate more explorations on intervention methods to minimize PNA and improve the behavior of medication nonadherence in general.

Limitations

This systematic review contains a few limitations. As articles included in this review were only sourced from 4 specific databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and ScienceDirect), the search might not have covered all available studies on PNA.

The exclusive topic also yielded few search results, with only 2 studies that produced qualitative research data, which used the methods of phone interview and focus group discussion, respectively. A majority of articles (n = 20) were quantitative in nature, with data obtained mostly from patients’ electronic medical and pharmacy records. These records captured information that we have categorized as patient and medication factors, such as demographics, medication regimen, and medication cost. As barriers to medication nonadherence are largely psycho-social in nature, PNA behavior cannot be comprehensively understood through the examination of these quantitative data alone. As previously discussed, the multifaceted characteristics of PNA also necessitate a deeper analysis of all factor categories and their shared relationships. The common methodology of assessing adherence in this review (electronic medical and pharmacy records) thus resulted in a skewed focus on the categories of patient and medication factors and implied a neglect of other factor groups that are essential to understanding PNA. Therefore, a major limitation of this review lies in the severe lack of qualitative research on PNA, suggesting that other more complex traits of nonadherence behavior might have been overlooked or are yet to be discovered.

Conclusions

This systematic review found a multitude of factors behind PNA, which we classified into 5 categories using a multilevel approach. Patient and health care provider factors play a key role in influencing patient decisions to initiate treatment. Those 2 categories share a dynamic relationship and are highly modifiable. As presented, patient attitudes toward taking medication is a primary patient-related barrier to initiating treatment and is often informed by health care providers, which has 2 implications: First, it suggests that any effort to reduce PNA should directly target these factor groups for a more effective outcome; second, it highlights the close association between patients’ outlooks and their health care providers, thereby providing a more concrete direction for intervention. As observed from current studies, health care professionals such as nurses and pharmacists actively contribute to minimizing PNA among patients by providing health care information. Therefore, future intervention could continue to boost the effect of health care providers, whether by encouraging greater transparency and shared decision making between physician and patient or by engaging nurses and counselors to help improve patients’ health literacy and their perceptions regarding taking medication. Stronger collaboration between patient and health care provider will act as a useful starting point in overcoming the complex and multifaceted behavior of PNA.

Finally, as the current pool of literature on PNA is highly limited, there is a great need for more well-designed studies and qualitative research into this topic and for future intervention studies on PNA to assess the close association between patient and health care provider factors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yap AF, Thirumoorthy T, Kwan YH.. Medication adherence in the elderly. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;7(2):64-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Latif S, McNicoll L.. Medication and nonadherence in the older adult. Med Health R I. 2009;92(12):418-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams AJ, Stolpe SF.. Defining and measuring primary medication non-adherence: development of a quality measure. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(5):516-23. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.5.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derose SF, Green K, Marrett E, et al. Automated outreach to increase primary adherence to cholesterol-lowering medications. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(1):38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin J, McCombs JS, Sanchez RJ, Udall M, Deminski MC, Cheetham TC.. Primary nonadherence to medications in an integrated healthcare setting. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(8):426-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thengilsdottir G, Pottegård A, Linnet K, Halldorsson M, Almarsdottir A, Gardarsdottir H.. Do patients initiate therapy? Primary nonadherence to statins and antidepressants in Iceland. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(5):597-603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raebel MA, Carroll NM, Ellis JL, Schroeder EB, Bayliss EA.. Importance of including early nonadherence in estimations of medication adherence. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(9):1053-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pottegård A, Christensen RD, Houji A, et al. Primary nonadherence in general practice: a Danish register study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(6):757-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalvi V, Mekoth N.. Patient nonadherence: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2017;30(3):274-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller NH, Hill M, Kottke T, Ockene IS.. The multilevel compliance challenge: recommendations for a call to action. Circulation. 1997;95(4):1085-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haustein S, Larivière V.. The use of bibliometrics for assessing research: possibilities, limitations and adverse effects. Incentives and Performance. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015:121-39. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Priem J, Taraborelli D, Groth P, Neylon C.. Altmetrics: a manifesto. 2010. Available at: http://altmetrics.org/manifesto/. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 13.Bornmann L. Do altmetrics point to the broader impact of research? An overview of benefits and disadvantages of altmetrics. J Informetr. 2014;8(4):895-903. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adamson AS, Suarez EA, Gorman AR.. Association between method of prescribing and primary nonadherence to dermatologic medication in an urban hospital population. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(1):49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheetham TC, Niu F, Green K, et al. Primary nonadherence to statin medications in a managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(5):367-73. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2013.19.5.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackson TH, Bentley JP, McCaffrey I, et al. Store and prescription characteristics associated with primary medication nonadherence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(8):824-32. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.8.824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashid N, Vassilakis M, Lin KJ, Kristy R, Ng DB.. Primary nonadherence to overactive bladder medications in an integrated managed care health care system. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(4):484-93. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.4.484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wroth TH, Pathman DE.. Primary medication adherence in a rural population: the role of the patient-physician relationship and satisfaction with care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(5):478-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackevicius CA, Li P, Tu JV.. Prevalence, predictors, and outcomes of primary nonadherence after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;117(8):1028-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.da Costa FA, Pedro AR, Teixeira I, Bragança F, Da Silva JA, Cabrita J.. Primary nonadherence in Portugal: findings and implications. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37(4):626-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, Serup J.. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(1):27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer AM, Schillinger D, Parker MM, et al. Health literacy and antidepressant medication adherence among adults with diabetes: the diabetes study of Northern California (DISTANCE). J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1181-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams LK, Joseph CL, Peterson EL, et al. Patients with asthma who do not fill their inhaled corticosteroids: a study of primary nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(5):1153-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wooldridge K, Schnipper JL, Goggins K, Dittus RS, Kripalani S.. Refractory primary medication nonadherence: Prevalence and predictors after pharmacist counseling at hospital discharge. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(1):48-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polinski J, Kesselheim A, Frolkis J, Wescott P, Allen-Coleman C, Fischer M.. A matter of trust: patient barriers to primary medication adherence. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(5):755-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J, Brenneman SK, Sazonov V, Modi A.. Reasons for not initiating osteoporosis therapy among a managed care population. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raebel MA, Ellis JL, Carroll NM, et al. Characteristics of patients with primary nonadherence to medications for hypertension, diabetes, and lipid disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):57-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison TN, Derose SF, Cheetham TC, et al. Primary nonadherence to statin therapy: patients’ perceptions. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(4):133-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karter AJ, Subramanian U, Saha C, et al. Barriers to insulin initiation. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):733-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds K, Muntner P, Cheetham TC, et al. Primary nonadherence to bisphosphonates in an integrated healthcare setting. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24(9):2509-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wamala S, Merlo J, Bostrom G, Hogstedt C, Agren G.. Socioeconomic disadvantage and primary nonadherence with medication in Sweden. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(3):134-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adamson AS. Electronic prescriptions more likely to be filled by patients. MedicalResearch.com. October 27, 2016. Available at: https://medicalresearch.com/author-interviews/electronic-prescriptions-likely-filled-patients/29121/. Accessed June 28, 2018.

- 33.Fallis BA, Dhalla IA, Klemensberg J, Bell CM.. Primary medication non-adherence after discharge from a general internal medicine service. PloS One. 2013;8(5):e61735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson MJ, Williams M, Marshall ES.. Adherent and nonadherent medication-taking in elderly hypertensive patients. Clin Nurs Res. 1999;8(4):318-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cizmic A, Heilmann R, Milchak J, Riggs C, Billups S.. Impact of interactive voice response technology on primary adherence to bisphosphonate therapy: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26(8):2131-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischer MA, Jones J, Wright E, et al. A randomized telephone intervention trial to reduce primary medication nonadherence. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(2):124-31. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leguelinel-Blache G, Dubois F, Bouvet S, et al. Improving patient’s primary medication adherence: the value of pharmaceutical counseling. Medicine. 2015;94(41):e1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]