Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Allergy immunotherapy (AIT) is the only available treatment that alters the natural course of allergies and has possible disease-modifying effects. AIT is administered primarily via subcutaneous injection delivered in a physician’s office. Few studies have been conducted in the United States or Canada to evaluate the costs of subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT).

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) describe SCIT administration processes, resources, and costs and (b) characterize the patient population receiving SCIT.

METHODS:

A multisite, prospective, observational time and motion study was conducted. Injection and wait times were collected by a third-party observer on 1 visit for each patient. Extract preparation processes were also observed. Site staff reported on treatment protocols, administrative time, supplies, and patient medical history. Patients responded to questionnaires on demographics, reasons for treatment, medication use, productivity, and travel time. Costs were estimated by applying unit costs to the time observations and the patient- and staff-reported data.

RESULTS:

A total of 670 SCIT patients were enrolled at 6 sites in the United States and 6 sites in Canada. Average age in the United States was 41 years (SD = 18) and 44 years (15) in Canada, with 10% of the patients aged ≥ 65 years. Annual incomes were over $100,000 for 40% of U.S. patients and 30% of Canadian patients. U.S. patients had over 4 times as many different allergens in their SCIT treatments as Canadian patients, with a mean of 18 versus 4. The most common reasons reported for starting SCIT was a “desire to cure allergies once and for all” (73%) and that “symptoms are not improved by allergy medications” (60%). Percentages of patients taking allergy medications in the 4 weeks prior to observation were 86% in the United States and 66% in Canada: antihistamines 75% United States, 54% Canada; inhaled corticosteroids 32% United States, 22% Canada. The predominant comorbidity was asthma, 43% United States, 24% Canada. Site protocols for build-up treatment phases were 1 to 2 injections per week for an average of 25 weeks (range 12-52). Maintenance phases were 1 injection every 3 to 4 weeks for an average of 4 years (range 2.5-5). Eight of the sites had total mean staff times per injection visit of 7 to 22 minutes; 1 site averaged fewer minutes, and 3 sites averaged more. Total direct medical costs were an average of $30 for Canadian patients per visit and $32 per visit for U.S. patients, half accounted for by the cost of the extract. Pre- and postinjection administrative tasks were the second largest driver of direct costs. Total injection visit-related time for patients, including round-trip travel time, averaged about 80 minutes per visit in the United States and in Canada.

CONCLUSIONS:

Analyses revealed substantial variation in SCIT regimens among sites, but the sites had commonalities in the injection process components. SCIT requires patient commitment to a long-term treatment regimen involving numerous clinic visits and resources for administration.

What is already known about this subject

Subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) is an established and effective form of allergy immunotherapy administered to allergic rhinitis patients unable to control symptoms with allergen avoidance and/or use of symptomatic medications. About 2%-9% of allergic rhinitis patients in the United States are treated with allergy immunotherapy.

Little is known about the process of SCIT administration, the usual care patient population, and costs associated with delivery of allergy immunotherapy in the United States and Canada.

What this study adds

This time and motion study provides insight into the SCIT administration process via direct observation of SCIT injections and site processes combined with medical history, resource utilization, and loss of productivity collected from patients, physicians, and retrospective chart review.

Extract costs, administrative time, and patient time were the primary drivers of the cost of SCIT, and while treatment regimens varied substantially among sites and patients, the overall injection processes were similar.

SCIT requires patient commitment to a long-term treatment regimen involving numerous clinic visits and resources for administration.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) alone or AR with conjunctivitis (ARC) affected 10%-30% of the population in 2011-2012, and prevalence rates are increasing worldwide.1,2 Physician-diagnosed AR/ARC has been estimated at approximately 8% of adults and 10% of children in the United States, and 20% of adults and 12% of children in Canada.3-6 AR/ARC is a risk factor for asthma, with up to 40% of AR subjects reporting asthma.1,7,8 AR/ARC is also associated with several other comorbidities including sinusitis, conjunctivitis, sleep disorders, and food allergies.1,9,10

Management of AR encompasses allergen avoidance, use of symptomatic pharmacologic agents, and specific allergy immunotherapy (AIT) for patients who respond inadequately to allergen avoidance and pharmacology.11,12 AIT is the only available treatment that alters the natural course of allergic disorder through its sustained efficacy and disease-modifying effects.13 Evidence suggests that AIT prevents development of new sensitizations14-17 and reduces the risk of children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis developing asthma.15,16,18-21 Therefore, AIT is considered a cost-effective treatment option that reduces allergic disease, comorbidities, medication use, and the number of days absent from school/work, while improving quality of life.22-24

AIT involves repeated administration of specific allergens to induce tolerance development. Two modes of AIT administration are currently prescribed in U.S. and Canadian clinical practice: subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) and sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT). SCIT is used for allergic rhinoconjunctivitis in adults and children in the United States and Canada. Two SLIT tablets were approved for use in the United States (April 2014) and Canada (late 2013) for treatment of grass pollen-induced allergies; a tablet for ragweed-induced allergies was also approved in both countries in April 2014. In the United States, SLIT drop immunotherapy using SCIT allergen extracts is an off-label treatment. According to the World Health Organization, SCIT “represents the standard modality of treatment” for allergy immunotherapy.1,25 Cox and Calderon (2010) estimate that 2%-9% of AR patients in the United States are treated with AIT,22 whereas Keith et al. (2012) report that 15%-22% of AR patients in Canada have been treated with AIT.5

Few studies have been conducted in the United States to observe the costs associated with AIT,13,26,27 and no published studies were found for costs of AIT in Canada. A study of Florida Medicaid claims between 1997 and 2009 indicated that patients who received immunotherapy incurred significantly lower per-patient total health care costs, outpatient costs, and pharmacy costs compared with a matched control group in an 18-month period.26 Another study compared patient out-of-pocket expenses for SCIT and SLIT drops and variations in insurance coverage.28

The present study was conducted to characterize SCIT administration processes, their associated resource needs and costs, and the patient population in Canada and the United States. This study collected data through a prospective time and motion (T&M) study methodology, with complementary patient survey and retrospective chart review components, which is a novel study design for this patient population.

Methods

Design

A prospective, observational study of SCIT administration was conducted in the United States and Canada, inclusive of patients naïve to treatment (no prior SCIT) and prevalent on treatment. As a study with a focus on descriptive, not comparative objectives, the target number of sites, specialties, and patients were based on considerations of face validity and feasibility, not on statistical power considerations. However, treatment-naïve patients were oversampled for investigation of potential differences in key outcomes in relation to patients prevalent on treatment.

Study site recruitment was initiated via invitation letters sent to prescribers of SCIT in the United States and Canada, specifically primary care practitioners, otolaryngologists, and allergists. Clinical practices were deemed eligible based on (a) administration of SCIT in sufficient patient volumes to reach the target sample size within project timelines, (b) ability to utilize a central institutional review board (IRB) for study approval, (c) availability of research staff to assist with data extraction, and (d) willingness to allow third-party observation of the injection visits. Data collection consisted of observation of SCIT processes through a T&M approach with complementary patient survey, facility questionnaire, and chart abstraction. The IRB approved the study protocol, the informed consent materials, and each of the clinical sites prior to data collection.

Patient Recruitment

English or French-speaking patients, aged 6 years and older, were recruited at a usual care visit for the administration of SCIT for the treatment of rhinitis, conjunctivitis, and/or asthma. Patients enrolled in a clinical trial, sensitized only to insect venom, latex, food, or drug, and patients receiving SLIT drops were excluded from the study.

Consent/assent was confirmed prior to the beginning of data collection for each patient. A convenience sample of consecutive patients scheduled to receive SCIT at each site was recruited until the target sample size was met.

Each patient was observed only once. Patients were not observed at visits when other injections were given in addition to SCIT, such as immunotherapy for the treatment of stinging or biting insect hypersensitivity, seasonal flu shots, or other medications.

Study Measures and Data Collection

Trained third-party observers collected T&M data consisting of injection and test times, patient wait times before and after SCIT, and allergen extract preparation (see Appendix A, available in online article). At 6 of the 7 sites that prepared their own allergen extracts, the preparation process was observed and timed at the per-patient level, for a total of 20-34 observations per site.

Site staff answered questions related to the typical site treatment protocol, administrative time per week, and supplies for injection and allergen extract preparation, with 1 such questionnaire per site. A brief retrospective chart review was conducted for each enrolled patient to capture medical history (number and types of allergens administered to the patient, start date of immunotherapy, allergy symptoms, and comorbid conditions) and number of allergy tests.

Each patient responded to a questionnaire on demographics, insurer type and out-of-pocket payments for SCIT, reasons for treatment, medication use, and medical resource utilization. In addition, patients completed an allergy-specific version of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire plus Classroom Impairment Questions (WPAI+CIQ-AS)29,30 to measure the impact of general allergies on work productivity, daily activities, and classroom impairment over the preceding 7 days, including number of hours missed from work or school.

Data Management and Quality Control

Anonymized data were collected on paper case report forms and entered into the study database with the aid of an optical character recognition system (DataFax, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada). All data were reviewed independently by 2 different reviewers; errors or inconsistencies generated on data collected by site staff (chart review, site questionnaire) generated follow-up queries to sites. Because of recall bias and the crosssectional nature of the patient observations that precluded patient follow-up, queries were not generated for patient questionnaires or T&M case report forms.

Analysis

Results were summarized descriptively by site, country, and phase of SCIT treatment (naïve vs. prevalent). Patient characteristics and outcomes are reported as country-level means, since few differences were found by site or phase of care. Time observations that were driven more by site practice than patient variability were characterized by describing the distribution of site means.

A basic model of the costs of a SCIT visit by site was built based on the time observations, patient- and staff-reported data, and unit cost data collected in this study. The cost perspective was that of society. National median wage rates by staff type (Appendix B, available in online article) were applied to staff time. Averages were not available by staff type for both countries. Site-reported administrative time per week was divided by site-reported visit volume for a per-visit estimate. Injection supplies and externally prepared extract were priced from major suppliers (Appendix C, available in online article).

To value the indirect cost of a patient’s time, average wage rates are commonly used as a point of reference.31 For a conservative nominal estimate, patient time was valued at 50% of the average national wage.

Results

Sites

A total of 12 sites were enrolled, 6 in Canada (5 allergists and 1 primary care physician) and 6 in the United States (4 allergists and 2 otolaryngologists). Locations were in Quebec, Ontario, and 6 U.S. states: Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Virginia, Indiana, Alabama, and New Mexico. Weekly total volume of SCIT patients per site ranged from 30 to 600.

Patients

Patients were enrolled from March to December 2012. Patient sample size was 670 (294 Canada, 376 United States) for all but the chart review, with site sample sizes ranging from 44 to 74; charts were reviewed for 293 Canadian patients and 377 U.S. patients. Based on feedback from site study coordinators, consent rates for invited patients were near 100%. Nevertheless, investigators from at least 2 sites did not invite adolescents who attended their SCIT visit without a parent or guardian because of logistical problems with the consent requirement.

Key patient demographics are shown in Table 1. Approximately 10% of patients were aged ≥ 65 years; 13% of U.S. patients and 4% of Canadian patients were children (aged < 18 years). The majority of patients were female, and most were of Caucasian race. Household incomes were fairly high, with incomes above $100,000 for 30% of Canadian patients and 40% of U.S. patients (percentage of those responding; all dollars [$] are for respective country unless otherwise stated. During the observation period, U.S. and Canadian dollar values were within 2%.)

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics by Country

| Characteristic | Percentage with Characteristic | |

|---|---|---|

| Canada N = 294 | United States N = 376 | |

| Age, % | ||

| < 18 | 4 | 13 |

| ≥ 65 | 9 | 10 |

| Mean (SD) | 44 (15) | 41 (18) |

| Female gender | 59 | 67 |

| Race, % | ||

| Caucasian | 81 | 86 |

| Black | 0.3 | 4 |

| Asian | 11 | 2 |

| Hispanic or Latin American | 1 | 6 |

| Other | 6 | 1 |

| Missing | 0.3 | 0 |

| Employment, % | ||

| Full time | 57 | 47 |

| Part time | 9 | 12 |

| Student | 9 | 15 |

| Retired | 10 | 11 |

| Unemployed | 9 | 11 |

| Other | 5 | 4 |

| Missing | 1 | 1 |

| Household income, % | ||

| < $35,000 | 16 | 11 |

| $35,000-$49,000 | 10 | 9 |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 14 | 15 |

| $75,000-$99,999 | 19 | 14 |

| > $100,000 | 25 | 33 |

| Missing | 17 | 18 |

| > $100,000, % of nonmissing | 30 | 41 |

Note: categories may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

SD = standard deviation.

When patients who were on their first visit were asked why they were starting SCIT, the most common reasons cited were a “desire to cure allergies once and for all” (73%) and that “symptoms are not improved by allergy medications” (60%).

Medical History

Table 2 describes the medical history of patients. The most commonly reported symptoms at initiation of AIT in both countries were nasal symptoms, sneezing, and itchy eyes, while the predominant comorbidity was asthma (24% Canada, 43% United States). U.S. patients consistently had over 4 times as many different allergens in their SCIT treatment as Canadian patients, with a mean of 18 versus 4; these allergens included weed allergens for over 80% of patients in both countries. In the 4 weeks prior to observation, allergy medications were taken by 66% of Canadian patients and 86% of U.S. patients: 54% and 75% took antihistamines while 22% and 32% took inhaled corticosteroids, respectively. Asthma medications were taken by 24% of Canadian patients and 35% of U.S. patients. The proportions were similar for both prevalent and naïve patients (result not shown in table). An epinephrine injection device was carried by half of the U.S. patients but by only about 10% of the Canadian patients.

TABLE 2.

Patient Medical History by Country

| Characteristic | Percentage with Characteristic | |

|---|---|---|

| Canada N = 293 | United States N = 377 | |

| Most common symptoms at initiation of SCIT, % | ||

| Nasal congestion | 62 | 72 |

| Rhinorrhea | 59 | 54 |

| Nasal pruritis | 14 | 20 |

| Sneezing | 35 | 53 |

| Itchy eyes | 32 | 50 |

| Tearing or watery eyes | 13 | 18 |

| Coughing | 23 | 38 |

| Most frequent comorbidities since start of immunotherapy, % | ||

| Asthma | 24 | 43 |

| Conjunctivitis | 1 | 20 |

| Sinusitis | 4 | 30 |

| Atopic dermatitis (eczema) | 8 | 9 |

| Urticaria (hives) | 7 | 5 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 3 | 9 |

| Other | 33 | 25 |

| None indicated | 52 | 26 |

| Treatment phase, % | ||

| Naïve | 36 | 18 |

| Prevalent | 64 | 81 |

| Missing | - | 0.8 |

| Number of different allergens contained in SCIT on day of observation, mean (SD) | 4 (3) | 18 (8) |

| Number of different allergens by count, % | ||

| 1 | 32 | 0.5 |

| 2-3 | 16 | 3 |

| 4-5 | 26 | 3 |

| 6-10 | 24 | 16 |

| 11-20 | 3 | 40 |

| 21+ | 0 | 38 |

| Common allergies for which patients are treated, summary level, % | ||

| Weeds | 83 | 87 |

| Mites | 55 | 80 |

| Trees | 48 | 87 |

| Grass | 48 | 80 |

| Animal | 23 | 84 |

| Mold/fungus | 15 | 60 |

| Cockroach | 0.3 | 19 |

| None of the above | 0 | 2 |

| Use of concomitant medications (in 4 weeks prior),a % | ||

| Allergy | 66 | 86 |

| Antihistamines | 54 | 75 |

| Nasal corticosteroids | 22 | 32 |

| Leukotrienes | 2 | 13 |

| Decongestants | 1 | 8 |

| Asthma | 24 | 35 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 23 | 34 |

| Eczema | 8 | 8 |

| Hives | 5 | 2 |

| Esophagitis | 1 | 1 |

| Prescription | 58 | 64 |

| Over the counter | 49 | 73 |

aCanadian and U.S. sample sizes for patient-reported medication were 294 and 376, respectively.

SCIT = subcutaneous immunotherapy; SD = standard deviation.

Site Treatment Protocols

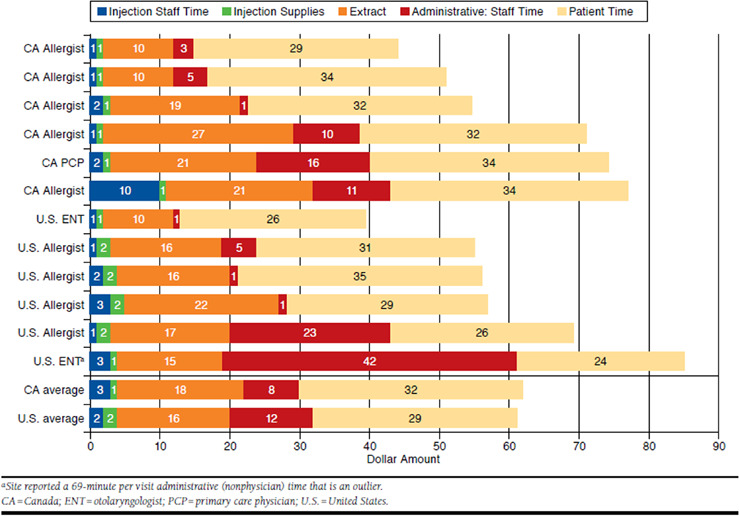

Sites reported typical protocols for patients on a full course of SCIT, i.e., excluding those on preseasonal treatments (Figure 1). Build-up phases varied in length from less than 4 months (3 sites in Canada), 4 to 5 months (4 sites), to 6 months or more (5 sites, including 1 Canadian site at 12 months). The frequency of build-up injections was every 1-1.5 weeks for 7 of the sites and more frequently than weekly for 5 sites. Protocol maintenance phases were usually reported as 4 years in duration, but 2 sites (1 in each country) reported 5 years and 2 Canadian sites reported 2 years. Nine of the sites maintained patients at 1 injection visit every 3 to 4 weeks. The other 3 sites (all U.S.) reported more frequent visits: every 2-4 weeks (2 sites) or every week (1 site).

FIGURE 1.

SCIT Build-Up and Maintenance Phases

Health Care Personnel Time

Site means for health care personnel time per visit for injection, allergen extract preparation, and administrative time are shown in Figure 2. Eight of the sites had total means per visit of 7 to 22 minutes; 1 site averaged fewer minutes, and 3 sites averaged more. Each component is discussed in turn below.

FIGURE 2.

Health Care Personnel Time Per Visit: Site Means (Minutes) by Component, Sorted by Country and Total Time

Site means for the time health care personnel spent in the exam room to administer injections were typically 1 to 3 minutes at Canadian sites, and 4 to 6 minutes at U.S. sites, with little variation among patients within a site. A portion of the country difference is due to the greater number of patients in the United States who received 2 injections as required for the greater number of allergens for which they were treated, as previously mentioned. A physician was present for each injection at 2 of the sites, which had relatively short mean times of 1 and 2 minutes. Registered nurses administered SCIT at 5 of the sites, with the remainder using licensed practical nurses, medical technicians, or medical assistants. Of the 670 visits observed, there were only 26 skin tests, physician consultations, or adverse events during the injection visit that would add time beyond the injection. One site performed peak flow tests on its patients with asthma, which took an average of 0.2 minutes to complete. Treatment-naïve patients receiving their first SCIT took about a minute longer than prevalent patients.

Allergen extract preparation was performed on-site for 2 Canadian and 5 U.S. sites, while the remaining 4 Canadian and 1 U.S. sites ordered from a vendor. Considering the number of injections supplied for each patient, average extract preparation times per injection visit varied by site from 0.1 to 2.4 minutes.

The administrative tasks related to SCIT that were reported by the most sites were (in order of frequency) ordering and processing extracts, generating charge slips, updating health records, registering patients, and updating billing records. The mean administrative time varied widely across sites, with 3 sites using no physician time and the others ranging from 1 to 11 minutes per visit for physicians and 1 site reporting that all administrative work was handled by the physician. Nonphysician administrative time per visit also varied by site: from 1 to 38 minutes (plus an outlier of 69 minutes).

Patient Time

Site means for total patient time in the office were 25 to 50 minutes, with standard deviations at each site ranging from 6 to 15 minutes. Times were fairly consistent because wait and injection times were short, and 8 of the 12 sites required a minimum 30-minute observation period after injections to check for adverse reactions. Mean preinjection wait times were 8 to 18 minutes in Canada and 5 to 10 minutes in the United States. Mean patient time in the exam room ranged from 1 to 6.5 minutes. Patient travel time to the office was 17-25 minutes (mean one-way) for each site. Total injection visit-related time for the patient, including round-trip travel time, averaged about 80 minutes in both the United States and Canada, with site means ranging from 70 to 95 minutes.

On the WPAI + CIQ-AS, patients in both countries reported a mean time of about 45 minutes missed from work in the previous 7 days because of their allergies.

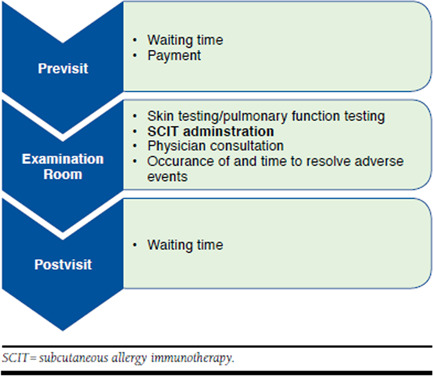

Costs Per Visit

The results of a basic model totaling the costs of a SCIT visit based on the time observations, patient and staff reports, and unit cost data collected in this study are displayed in Figure 3. The mean costs of staff time and supplies for giving the injection, the extract, and administrative time and a nominal valuation of the patient’s time are shown for each site, along with country averages. The total medical costs per visit by site ranged from $15 to $43 in Canada and $13 to $61 in the United States. Country means were $30 in Canada and $32 in the United States. The medical cost is matched by the value of patient time (at 50% of the national wage): $32 Canada, $29 United States.

FIGURE 3.

Costs Per Visit: Site and Country Means ($) by Component, Sorted by Country and Total Cost

The per visit cost of the extract itself—$16 Canada, $18 United States (mean)—was the largest component and accounted for half of the medical costs, whether prepared by the physician or ordered from a supplier. Administrative costs were the second largest component—$8 Canada, $12 United States—but varied more, from $1 to $42, and had a large impact on site-to-site variation in cost. (If the $42 administrative cost outlier was excluded, the mean U.S. cost would be reduced by $6.) The staff costs for the injection itself were much lower ($3 Canada, $2 United States); faster injection times in Canada relative to the United States were offset by 2 sites that bore the cost of the physician being in the exam room for the injection. Staff time costs were proportionate to the average wage of the mix of staff (e.g., physician, registered nurse, and licensed practical nurse) performing the task.

Discussion

While Canadian and U.S. practice guidelines present a standardized approach and algorithm for immunotherapy,32,33 the personalized nature of SCIT is acknowledged and reflected in the visit schedules they present for the build-up and maintenance phases. The most prominent protocol variations observed in this study across specialties and sites were the frequency of build-up visits along with the length of the buildup (from less than 4 months to 12 months) and maintenance phases (2-5 years)—differences likely driven by selected initial dosing pattern and patient response to treatment. A published study of the time required to reach maintenance dose of SCIT reported a range of 76-720 days at 1 site, influenced by gender, asthma, and patient age.34

Few studies have examined the costs of allergy immunotherapy in North America. One recent retrospective data analysis and 1 model compared the cost of AIT with continued use of symptomatic medications and reported an economic advantage for AIT.26,35 The present study aimed to expand on this evidence by examining the process and population in detail, including staff time, supplies for injections, extract preparation, administrative tasks, and patient time for wait and travel, as well as patient history, administered antigens, and symptomatic medication.

Based on the data gathered, the medical cost of a SCIT visit is estimated to average $30 in both countries, with the total staff times and times by component varying considerably from site to site. Although the sites are too few to be representative of the countries, the country totals provide a sound basis for a discussion of the most significant cost drivers. The average cost of the allergens for injection, whether prepared by the physician or ordered from a supplier, accounted for half of the medical cost. The degree to which sites could use prepared mixtures of common allergens was likely an important driver of preparation times. For comparison, a study that included a cost model of SCIT therapy in Canada implied a cost of $42 per visit for physician and extract costs (as calculated by the authors).36 Given the varying protocols reported by sites in this study and a $30 cost per visit, the medical costs alone of a complete course of SCIT treatment for a fully compliant patient could range from roughly $1,000 to $4,000. Build-up costs would make up $400 to $1,500 and annual maintenance $400 to $500 per year. Considering the range of per-visit costs across sites of $15 to $61, these total costs could be half or twice as high.

Payments to physicians for these costs come from insurers and patients. While reimbursement practices were not a part of this study, in the United States, there are specific medical procedure codes for SCIT injections and allergens for injection supplied or purchased by the physician. In Quebec and Ontario, the Canadian province covers the physician portion of the visit, and the patient’s public or private drug insurance covers a portion of the allergen extract cost.

This study found patient time to be substantial, averaging 80 minutes per visit consistently across sites, including travel time and postinjection wait time, although patients reported missing only half that amount of time from work, indicating some schedule flexibility. Assigning a value of half the national wage rate for the patient’s total visit time results in a $30 cost per visit; this is as high as the medical cost. With weekly visits during the build-up phase and monthly visits during the maintenance phase, patient time is an important component of SCIT. In the long run, however, an effective course of treatment can pay off for the patient in terms of quality of life and productivity.22,24

This study presents patient demographic and clinical characteristics infrequently reported outside the clinical trial setting. The demographic results demonstrated a relatively high household income of patients and that almost two thirds of the patients were female. U.S. patients had a mean of 18 allergens in their treatment and Canadian patients had a mean of 4. This difference may reflect the influence of Canadian guidelines, which recommend treatment with clinically relevant allergens, along with differences in the prevalence of symptom-inducing allergens (i.e., plant species) between the United States and Canada. While more U.S. patients accordingly received 2 injections in a single visit, the impact on staff time was minimal compared with other activities. The potentially higher ingredient cost was offset by the higher portion of U.S. sites that prepared their own allergen extracts rather than ordering from suppliers. Cox and Calderon reported similar differences when comparing the approach to SCIT administration in the United States and Europe, where multiple allergens (U.S.) versus single allergens (Europe) were administered to patients.22 This study further highlights differences in approach for the United States compared with other countries.

About 60% of patients reported concomitant use of prescription allergy medications, although they were on SCIT. Asthma was a comorbidity for about one third of the patients overall (43% United States, 24% Canada). This is comparable with a large nationally representative telephone survey of Canadian allergic rhinitis patients, where 27% reported having asthma.5 The proportions reporting various symptoms were also comparable with those in our study.

Limitations

The generalizability of the results is limited by the small number of sites included in the study, as well as the geographic and seasonal variability in allergens across sites. Clinical practices without sufficient research staff or patient volume were unable to participate, which may limit generalizability to the high volume practices likely to treat the majority of SCIT patients. The extent to which patients and site practice patterns are representative of other allergy practices is unclear. Nevertheless, the range of site-level results among 12 sites was sufficiently small to be informative, and a large cohort of patients was enrolled. Patient characteristics and endpoints such as allergy symptoms, work impairment, and travel time are less affected by site practice (albeit allergies and demographics are influenced by site location). Several sites treated only adult patients, resulting in an underrepresentation of care and outcomes experienced by children and adolescents.

Direct observation of administrative time was not possible, and site staff had difficulty estimating the time to complete administrative tasks, which is 1 component of the cost calculation. This study did not attempt to collect data related to persistence or adherence and therefore does not provide an average cost of the complete SCIT treatment protocol, but rather a pervisit cost estimate. Persistence with therapy would be a good subject for future research.

Limitations of all T&M studies include the risk of observers interfering with care patterns by their presence (the Hawthorne effect) and the precision of the study data given the possibility of human timing errors.37,38 These risks were mitigated with thorough on-site training of all observers by a study investigator, including a quality review of the first 2 observations performed.

Conclusions

SCIT requires patient commitment to a long-term treatment regimen involving numerous clinic visits and resources for administration. This T&M study uniquely combined direct observation of SCIT injections administered in the United States and Canada with medical history and health outcomes collected from patients, physicians, and retrospective chart review. Analyses revealed substantial variation in SCIT regimens among and between countries and clinical settings, yet commonality was seen in the overall injection process. Extract costs and patient time were the primary drivers of the cost of SCIT.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of S. Hubbard, K. Payne, and S. Tao (United BioSource Corporation), for contributions to study design, implementation, and reporting, and S. Macker and K. Fraeman (Evidera), for contributions to data management and analytics.

APPENDIX A. Overview of Time and Motion Data Collection Points for SCIT Administration

APPENDIX B. Wage Rates Per Hour

| Canada (CAN$)a | United States (US$) | |

|---|---|---|

| Health care personnel, medianb,c | ||

| Specialty physician | 79 | 89 |

| Registered nurse | 35 | 32 |

| Licensed practical nurse | 24 | 20 |

| Medical secretary, records | 20 | 16 |

| All workers, meanc,d | 24 | 22 |

aAt time of observation (2012), Canadian and U.S. dollar values were within 2%.

bData from Statistics Canada. Labour Force Survey. Working in Canada—wage report. Median wages for specific occupations. Reference period 2011-2012. February 27, 2014. Available at: http://www.workingincanada.gc.ca/wage-outlook_search-eng.do?reportOption=wage. Accessed September 17, 2015.

cData from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2012 national occupational employment and wage estimates. January 27, 2014. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm. Accessed September 17, 2015.

dData from Statistics Canada. Average hourly wages of employees by selected characteristics and occupation, December 2012. January 16, 2013. Available at: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/labr69a-eng.htm. Accessed September 17, 2015.

APPENDIX C. Supply Costs

| Item | Cost Per Injected 1 cc |

|---|---|

| Extract: supplier prepared | $11.43-$19.16 |

| Personalized maintenance concentrate, 10 cc | |

| ≤ 6 allergens, $114.32 | |

| 13-15 allergens, $191.58a | |

| Extract: physician prepared, total cost | $8.12 |

| Treatment extract averaged over all types, 50 cc bottle $390 (range $246-$694)a | $7.80 |

| Mixing syringes $0.12 each,a assume 15 per prepared 10 cc vial = $1.80 | $0.18 |

| Vial 10 cc $1.18a | $0.12 |

| Gloves, 2 at $0.10 per prepared 10 cc vial = $0.20b | $0.02 |

| Supplies for patient injection | $0.79 |

| Syringe 1 cc, gloves, Benadryl spray, alcoholb |

Note: U.S. and Canadian sites used the suppliers or similar ones shown in the following footnotes.

aPricing data from Greer Labs, Human allergy product price list, April 2012-March 2013.

bPricing data from Physician Sales & Service. Wareham, MA. February 2013. Available at: www.myPSS.com. Accessed September 17, 2015.

cc = cubic centimeter.

References

- 1.Pawankar R, Canonica GW, Holgate ST, Lockey RF.. WAO White Book on Allergy 2011-2012: executive summary. 2011. Available at: http://www.world-allergy.org/publications/wao_white_book.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2015.

- 2.Malling HJ, Bousquet J.. Subcutaneous immunotherapy for allergic rhino-conjunctivitis, allergic asthma and prevention of allergic diseases. In: Lockey RF, Ledford DK, eds.. Allergens and Allergen Immunotherapy: Subcutaneous, Sublingual and Oral. 5th ed. New York: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group; 2014:349-60. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, Peregoy JA.. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat 10. 2012;(252):1-207. Available at:.http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_252.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bloom B, Cohen RA, Freeman G.. Summary health statistics for U.S. children: National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat 10. 2011;(250):1-80. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_250.pdf. Accessed September 17, 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keith PK, Desrosiers M, Laister T, Schellenberg RR, Waserman S.. The burden of allergic rhinitis (AR) in Canada: perspectives of physicians and patients. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2012;8(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorksten B, Clayton T, Ellwood P, Stewart A, Strachan D; ISAAC Phase III Study Group. . Worldwide time trends for symptoms of rhinitis and conjunctivitis: Phase III of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19(2):110-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerra S, Sherrill DL, Martinez FD, Barbee RA.. Rhinitis as an independent risk factor for adult-onset asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(3):419-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gentile D, Bartholow A, Valovirta E, Scadding G, Skoner D.. Current and future directions in pediatric allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(3):214-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lockey RF, Ledford DK, eds.. Asthma, Comorbidities, Co-Existing Conditions, and Differential Diagnoses. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampson H, Eigenmann PA.. Food allergy and intolerance. In: Mygind N, Naclerio R, eds.. Allergic and Non-Allergic Ehinitis. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahls C. In the clinic. Allergic rhinitis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(7):ITC4-1-ITC4-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price D, Bond C, Bouchard J, et al. International Primary Care Respiratory Group (IPCRG) Guidelines: management of allergic rhinitis. Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15(1):58-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lockey RF, Hankin CS.. Health economics of allergen-specific immunotherapy in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1):39-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eng PA, Borer-Reinhold M, Heijnen IA, Gnehm HP.. Twelve-year follow-up after discontinuation of preseasonal grass pollen immunotherapy in childhood. Allergy. 2006;61(2):198-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eng PA, Reinhold M, Gnehm HP.. Long-term efficacy of preseasonal grass pollen immunotherapy in children. Allergy. 2002;57(4):306-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marogna M, Tomassetti D, Bernasconi A, et al. Preventive effects of sublingual immunotherapy in childhood: an open randomized controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;101(2):206-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pajno GB, Barberio G, De Luca F, Morabito L, Parmiani S.. Prevention of new sensitizations in asthmatic children monosensitized to house dust mite by specific immunotherapy. A six-year follow-up study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31(9):1392-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobsen L, Valovirta E.. How strong is the evidence that immunotherapy in children prevents the progression of allergy and asthma? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7(6):556-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moller C, Dreborg S, Ferdousi HA, et al. Pollen immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis (the PAT-study). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109(2):251-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niggemann B, Jacobsen L, Dreborg S, et al. Five-year follow-up on the PAT study: specific immunotherapy and long-term prevention of asthma in children. Allergy. 2006;61(7):855-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novembre E, Galli E, Landi F, et al. Coseasonal sublingual immunotherapy reduces the development of asthma in children with allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(4):851-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox L, Calderon MA.. Subcutaneous specific immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a review of treatment practices in the U.S. and Europe. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(12):2723-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blaiss MS. Allergic rhinitis: direct and indirect costs. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(5):375-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nasser S, Vestenbaek U, Beriot-Mathiot A, Poulsen PB.. Cost-effectiveness of specific immunotherapy with Grazax in allergic rhinitis co-existing with asthma. Allergy. 2008;63(12):1624-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bousquet J, Lockey R, Malling HJ.. Allergen immunotherapy: therapeutic vaccines for allergic diseases. A WHO position paper. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998;102(4 Pt 1):558-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hankin CS, Cox L, Bronstone A, Wang Z.. Allergy immunotherapy: reduced health care costs in adults and children with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(4):1084-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hankin CS, Cox L, Lang D, et al. Allergen immunotherapy and health care cost benefits for children with allergic rhinitis: a large-scale, retrospective, matched cohort study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;104(1):79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seiberling K, Hiebert J, Nyirady J, Lin S, Chang D.. Cost of allergy immunotherapy: sublingual vs subcutaneous administration. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2(6):460-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reilly MC, Tanner A, Meltzer EO.. Work, classroom and activity impairment instruments: validation studies in allergic rhinitis. Clin Drug Invest. 1996;11(5):278-88. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM.. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sculpher M. The role and estimation of productivity costs in economic evaluation. In: Drummond M, McGuiere A, eds.. Economic Evaluation in Health Care: Merging Theory with Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001:94-112. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox L, Nelson H, Lockey R, et al. Allergen immunotherapy: a practice parameter third update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(1 Suppl):S1-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leith E, Bowen T, Butchey J, et al. Consensus Guidelines on Practical Issues of Immunotherapy-Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (CSACI). Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2006;2(2):47-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jourdy DN, Reisacher WR.. Factors affecting time required to reach maintenance dose during subcutaneous immunotherapy. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2(4):294-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy JL, Robinson D, Christophel J, Borish L, Payne S.. Decisionmaking analysis for allergen immunotherapy versus nasal steroids in the treatment of nasal steroid-responsive allergic rhinitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28(1):59-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dranitsaris G, Ellis AK.. Sublingual or subcutaneous immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis: an indirect analysis of efficacy, safety and cost. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(3):225-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fox NS, Brennan JS, Chasen ST.. Clinical estimation of fetal weight and the Hawthorne effect. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;141(2):111-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCarney R, Warner J, Iliffe S, van Haselen R, Griffin M, Fisher P.. The Hawthorne effect: a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]