Abstract

BACKGROUND:

In polypharmacy patients, medication therapy management (MTM) services provide a comprehensive review of current medications and future treatment goals. Pharmacogenetics (PGx) may further optimize the identification of potential drug therapy problems (DTPs); however, the clinical utility of PGx information with a clinical decision support tool (CDST) in an MTM setting in identifying DTPs has not been systematically assessed.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the clinical utility of an MTM service enhanced by pharmacogenetic test results and a clinical decision support tool.

METHODS:

This study was a post hoc analysis of the data obtained from an open-label, randomized, observational trial. Polypharmacy patients eligible for MTM service were randomly assigned to 3 intervention arms: standard MTM (SMTM), MTM incorporating CDST (CMTM), and CMTM further enhanced by PGx test results of CYP450 and VKORC1 enzymes (PGxMTM). Allocation for this post hoc analysis was based on patient adherence to the research protocol and completion of a PGx test. The number of DTPs per patient was compared across the 3 arms using analysis of variance. In addition, the frequency of serious DTPs as a categorical variable (grade 3 or above vs. lower grade) was compared across the 3 arms between PGx driven and non-PGx driven DTP recommendations. Statistical significance was tested using the chi-square test. The level of agreement between the DTP seriousness and the acceptance made by prescribers was presented as Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

RESULTS:

Numbers of patients after cohort reallocation based on completion of PGx testing were 104, 180, and 58 for the SMTM, CMTM, and PGxMTM arms, respectively. On average, 3.08 DTPs were identified for each patient, which was nearly identical across all 3 arms. Blinded clinical pharmacists considered seriousness (grade 3 or 4) in 31% of the PGx-related DTPs in comparison with 4.9% of the non-PGx DTPs (P < 0.001). The more serious (i.e., grade 3 or above) DTP recommendations were more likely to be accepted by prescribers with the odds ratios of 1.95 (P = 0.05) and 2.39 (P = 0.15), when the analysis was performed for all DTPs and DTPs from the PGxMTM arm only, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

MTM enhanced by PGx testing and the clinical decision support tool did not increase the number of DTPs identified. However, PGx testing and the decision support software helps pharmacists determine more serious DTPs, and resulting subsequent recommendations were more readily accepted by a prescriber. Future study of the patient safety outcomes and overall health care costs associated with the utility of the decision support is warranted.

What is already known about this subject

Pharmacogenetic (PGx) polymorphism represents an independent risk factor for frequent hospitalizations in older adults with polypharmacy.

The majority of physicians agree that genetic variations may influence drug response, but only about 10% feel adequately informed about PGx testing.

PGx profiling using a clinical decision support tool has been associated with a decrease in health care resource utilization in older adults who have been exposed to polypharmacy.

What this study adds

The use of a clinical decision support tool and pharmacogenetic information did not increase the total amount of information that a health care provider has to review.

Pharmacists identified more serious recommendations that were readily accepted by prescribers.

Adrug therapy problem (DTP) is an event or circumstance, such as an adverse drug reaction (ADR) or drug-drug interaction (DDI), related to drug treatment that may interfere with treatment goals.1 Several studies have demonstrated that DTPs increase resource utilization and medical costs, as well as decrease quality of life.2,3 Given the fact that many DTPs are preventable by a medication review, medication therapy management (MTM) can potentially decrease the number, as well as seriousness, of DTPs.4,5

In 2004, MTM was defined as a service that optimizes therapeutic outcomes for individual patients.6 The need for these services has increased since 2004 and has been accompanied by improvements in outcomes, such as drug cost, appropriate medication use, health care resource utilization (HRU), and overall patient well-being.5 However, even with MTM, outcomes vary substantially among patients. This variability may be explained by differences in individual patient genetics.7 Pharmacogenetic (PGx) testing is a new, evolving area of clinical practice that has the potential to predict and reduce adverse drug reactions (ADRs) that arise from genetic variance. PGx test results have been used to identify drug-gene interactions (DGIs) that occur when a patient’s genetic results affect the metabolism or response of their medications. In a recent publication, DGIs and drug-drug-gene interactions (DDGIs, or DGIs compounded by a drug-drug interaction) accounted for approximately 34% of significant interaction warnings that can potentially lead to side effects or decreased effectiveness. Further, clinical decision support tools (CDSTs) are now available that help pharmacists identify DDGIs, which are potentially linked to more serious DTPs.8 Such information can be delivered to the MTM pharmacist directly or proactively entered into an electronic medical record through an applied program interface.

Previous studies have estimated the effect of pre-emptive PGx testing to determine potential DDI/DGI/DDGIs on HRUs and costs in the setting of polypharmacy.9 However, whether the incorporation of genetic information into traditional MTM services helps pharmacists to identify a greater number and level of seriousness of DTPs, specifically when the decision was supported by a DDI/DGI/DDGI CDST, is largely unknown. The purpose of this study was to test the clinical utility of PGx profiling in combination with a CDST as part of standard MTM in polypharmacy patients.

Methods

Patient Recruitment

MTM beneficiaries who were naive to MTM counseling over the past 12 months were identified from the Magellan Health database and recruited by pharmacy staff using a predefined protocol. Eligible patients had to meet the following Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services-approved MTM eligibility: currently taking 6 or more chronic medications, having 3 or more chronic disease states, and incurring Medicare-mandated medication-related costs in the previous quarter.10 Those who were unable to participate in an MTM encounter, due to current living situation or mental health barriers defined by the Brief Interview for Mental Status score of less than 13 points, were excluded.

The study cohorts consisted of 1 standard MTM (SMTM) arm as a control and the following 2 intervention arms: MTM plus CDST (CMTM) and PGx testing in addition to CMTM (PGxMTM). SMTM patients received Magellan Health’s standard MTM service over the phone. In addition to the standard MTM service by Magellan, pharmacists were able to use YouScript CDST software (YouScript, Seattle, WA) to identify DTPs for those who were assigned to the CMTM group. Patients who were assigned to the PGxMTM group were contacted by MTM phone counselors for instruction and subsequently received a buccal swab test kit. Samples were collected via postage-paid package and were analyzed at Genelex (Seattle, WA), a laboratory certified by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments and accredited by the College of American Pathologists. Results were entered into the CDST to further identify DTPs, including DDIs, DGIs, and DDGIs.8 The polymerase chain reaction assays for the PGxMTM arm captured genotypes of cytochrome P (CYP)2D6, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and VKORC1 at an analytical sensitivity and specificity of > 99%. Prescribers received an MTM-DTP report for each patient that included PGx test results and prescribing suggestions to address the identified DTPs.

Study coordinators and participating physicians enrolled patients for the SMTM arm before randomization between CMTM and PGxMTM. After the number of patients for the SMTM group exceeded 100, patients were then assigned to either CMTM or PGxMTM based on their birth year: odd years were enrolled in the PGxMTM group, and even years were were enrolled in the CMTM group.

During the initial MTM session, pharmacists who administered the MTM session documented age, gender, active medications, and history of ADRs. To summarize the types of drugs reviewed by pharmacists, active medications were grouped into 50 therapeutic classes based on the Magellan drug class code. The protocol was approved by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board in March 2015 and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02428660).

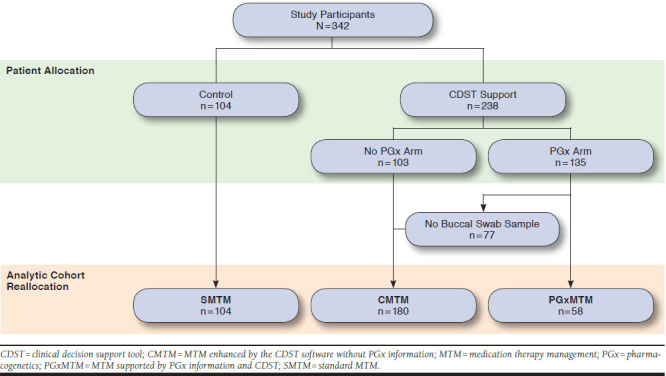

Study Group Reallocation: Analytic Cohort

Because of the high dropout of patients from the PGxMTM arm before the buccal swab test, an intention-to-treat analyses did not provide insight into the utility of PGx service. Instead, this post hoc analysis reassigned those individuals who failed to provide the PGx sample to the CMTM cohort. Because these participants did not undergo the PGx profiling, the MTM they received was identical to the CMTM group (i.e, MTM plus CDST without PGx testing; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Patient Recruitment for the Randomized Trial and Per Protocol Patient Reassignment for the Post Hoc Analysis

Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the average number of DTPs per patient for each study arm. The secondary outcome was DTP seriousness captured from pharmacy plan data. Pharmacists who were blinded from the cohort assignment and source of information for each DTP (i.e., standard MTM tools and CDST with or without PGx results) labeled each DTP with the level of seriousness. The seriousness of each DTP was ranked from grade 1 to 5, from least to most concerning, based on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services “Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events”11:

Grade 1: asymptomatic or mild symptoms; required clinical or diagnostic observations only; intervention not indicated

Grade 2: moderate; minimal, local or noninvasive intervention indicated; limiting age-appropriate instrumental activities of daily living

Grade 3: Severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; hospitalization or prolongation of hospitalization indicated; disabling; limiting self-care activities of daily living

Grade 4: Life-threatening consequences; urgent intervention indicated

Grade 5: Death related to adverse event

There were no grade 5 DTPs observed in this study. DTPs classified as grade 3 or above were grouped into a “serious DTPs” category because the count of the grade 4 DTPs was insufficient to test a statistical significance. Specific examples of DTPs and their grades are presented in the Appendix (available in online article).

A diagnostic test has utility in a clinical practice when it potentially influences and improves clinical decision. The clinical utility of a DTP recommendation was captured by the association between the DTP grade (i.e., serious vs. less serious) and prescriber’s acceptance of the recommendation. Any therapeutic changes corresponding to a DTP recommendation after 12-months of follow-up from study enrollment were considered an acceptance.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to compare baseline characteristics across the 3 groups to rule out potential sources of bias and confounders from this post hoc analysis. Continuous variables, including age by year, number of active medications, and number of ADRs at baseline, were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) across the 3 per protocol reassigned cohorts. Categorical variables, including gender and the therapeutic class of active medication, were compared using chi-square tests and Fisher exact tests were used for analysis when the number of patients receiving drugs in a specific therapeutic class was less than 5.

The number of DTPs per patient was analyzed using descriptive statistics for continuous variables and compared across the 3 study arms using ANOVA. Using a generalized linear model (GLM) with an identical or log-link, the number of DTPs were regressed on the group allocation and the potential confounders whose P value was less than 0.1 from the chi-square test for the baseline comparison. Within each MTM cohort, the contributions that PGx results and the CDST made were delineated by the number of DTPs and their proportions.

Statistical analyses for the secondary outcome (i.e., DTP seriousness) was better presented with the DTP as a unit of analysis, rather than the treatment group assignment for a patient. The proportions of the serious DTPs were presented in a proportional bar chart across the treatment arms and as a pie chart across the sources of information, either assisted by PGx test results or not. Their significance was analyzed via a chi-square test. Using a logistic regression model, an odds ratio (OR) was calculated for “serious DTP” versus “less serious DTP” (i.e., grade 3 or above vs. grade 1 or 2) for the PGx identified DTPs. To rule out the influence of the group assignment, this DTP seriousness analysis was further limited to the DTPs from the PGxMTM group.

Whether the seriousness of a given DTP was associated with utility in a clinical decision was presented as an OR of the DTP being accepted for the serious versus less serious DTPs. Cohen’s kappa coefficient estimated the agreement between the DTP seriousness determined by pharmacists and the acceptance made by prescribers.12

Results

This randomized trial enrolled 342 patients and assigned 104 subjects to the SMTM arm, 103 to the CMTM arm, and 135 to the PGxMTM arm. Of the patients who were assigned to the PGxMTM arm and agreed to participate, 77 failed to provide the buccal swab test sample and consequently were classified as CMTM for the analysis. Thus, the number of patients in the analytic SMTM, CMTM, and PGxMTM arms were 104, 180, and 58, respectively (Figure 1). On average, participating patients were aged 75 years, took 11 medications, and had 6 conditions across the 3 arms. Patients who completed the buccal swab test had a greater number of baseline ADRs (0.76) than the other 2 analytic arms (0.47 for CMTM and 0.44 for SMTM), which was marginally significant (P = 0.06). The therapeutic classes of the baseline active medications were similar across the 3 arms (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| SMTM (n = 104) | CMTM (n = 180) | PGxMTM (n = 58) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous variables, mean (± SD) | ||||

| Number of current conditions | 6.15 (2.21) | 6.61 (2.59) | 6.52 (2.80) | 0.34 |

| Number of active medications | 11.16 (3.79) | 11.49 (4.32) | 11.47 (4.13) | 0.80 |

| Number of ADRsa | 0.44 (0.76) | 0.47 (0.85) | 0.76 (1.17) | 0.06 |

| Age, years | 75.06 (7.38) | 75.16 (8.27) | 74.17 (6.34) | 0.69 |

| Categorical variables, n (%) | ||||

| Gender (female) | 50 (48.1) | 79 (43.9) | 17 (29.3) | 0.06 |

| Therapeutic classes of active medicationsb | ||||

| Hypertension | 95 (91.3) | 166 (92.2) | 55 (94.8) | 0.72 |

| Lipid disorder | 79 (76.0) | 127 (70.6) | 46 (79.3) | 0.34 |

| Nutrition: vitamins and minerals | 80 (76.9) | 124 (68.9) | 45 (77.6) | 0.23 |

| Coagulation disorder | 60 (57.7) | 118 (65.6) | 39 (67.2) | 0.33 |

| Antidiabetic agents | 47 (45.2) | 84 (46.7) | 20 (34.5) | 0.26 |

| Antacid/antiulcer | 44 (42.3) | 78 (43.3) | 29 (50.0) | 0.61 |

| Psychiatry | 41 (39.4) | 76 (42.2) | 27 (46.6) | 0.68 |

| Cardiovascular, NCE | 31 (29.8) | 70 (38.9) | 19 (32.8) | 0.28 |

| Genitourinary disorder | 36 (34.6) | 58 (32.2) | 21 (36.2) | 0.83 |

| Asthma/COPD | 26 (25.0) | 53 (29.4) | 18 (31.0) | 0.64 |

| Allergy/cough/cold | 24 (23.1) | 44 (24.4) | 20 (34.5) | 0.24 |

| Thyroid disorder | 24 (23.1) | 49 (27.2) | 9 (15.5) | 0.19 |

| Pain medication, opioids | 18 (17.3) | 48 (26.7) | 14 (24.1) | 0.20 |

| GI, NCE | 24 (23.1) | 39 (21.7) | 12 (20.7) | 0.93 |

| Seizure | 18 (17.3) | 39 (21.7) | 15 (25.9) | 0.42 |

| Pain, anti-inflammatory | 19 (18.3) | 41 (22.8) | 8 (13.8) | 0.29 |

| Pain, non-narcotic, NCE | 19 (18.3) | 25 (13.9) | 8 (13.8) | 0.58 |

| Corticosteroids | 12 (11.5) | 25 (13.9) | 6 (10.3) | 0.72 |

| Hematopoietic therapy | 12 (11.5) | 25 (13.9) | 5 (8.6) | 0.55 |

| Antiplatelet agents | 13 (12.5) | 18 (10.0) | 8 (13.8) | 0.67 |

| Eye/ear disease | 8 (7.7) | 16 (8.9) | 8 (13.8) | 0.42 |

| Gout | 5 (4.8) | 15 (8.3) | 6 (10.3) | 0.38 |

| Osteoporosis | 8 (7.7) | 12 (6.7) | 4 (6.9) | 0.95 |

| Arrhythmia | 6 (5.8) | 14 (7.8) | 3 (5.2) | 0.71 |

| Skeletomuscular disorder | 3 (2.9) | 13 (7.2) | 3 (5.2) | 0.30 |

aADRs reported or captured on the date of the initial MTM session.

bTherapeutic class based on the drug class code provided by the MTM. Summary of therapeutic classes that was used in more than 5% of participating patients.

ADRs = adverse drug reactions; CDST = clinical decision support tool; CMTM = MTM enhanced by the CDST software without pharmacogenetic information;

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GI = gastrointestinal; MTM = medication therapy management; NCE = not classified elsewhere; PGx = pharmacogenetics;

PGxMTM = MTM supported by PGx information and CDST; SD = standard deviation; SMTM = standard MTM.

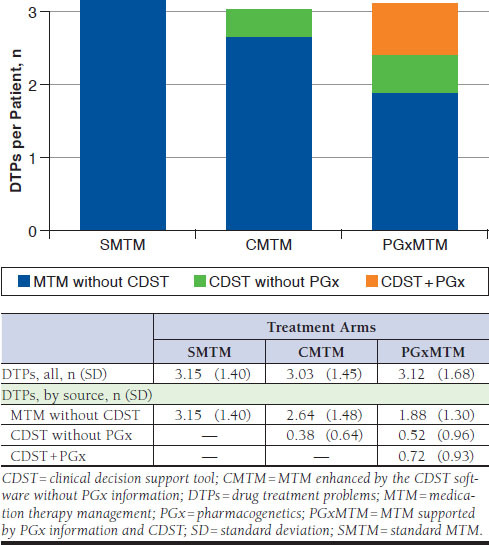

For the 342 enrolled patients, 1,054 DTP recommendations were made, meaning that each patient received 3.08 DTP recommendations on average. The mean numbers of DTPs identified were similar across the 3 analytic groups, with 3.15, 3.03, and 3.12 for the SMTM, CMTM, and PGxMTM groups, respectively (Figure 2). The total number of DTPs identified was not statistically significant across the 3 groups (ANOVA, P = 0.77), even after being adjusted for gender and the number of baseline ADRs (log-link GLM: P = 0.35 for PGxMTM vs. SMTM, P = 0.74 for PGxMTM vs. CMTM; identity-link GLM: P = 0.46 for PGxMTM vs. SMTM, P = 0.86 for PGxMTM vs. CMTM).

FIGURE 2.

The Number of DTPs Identified

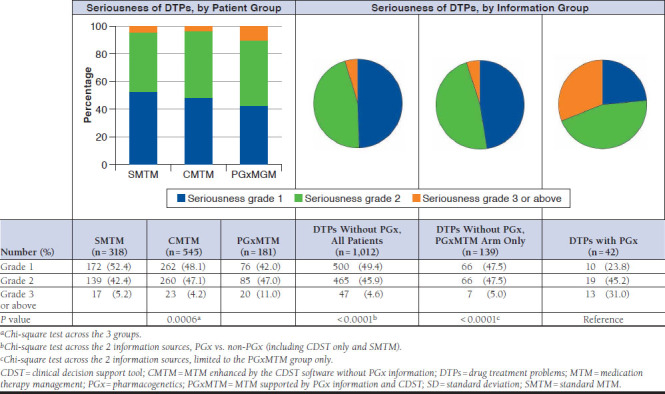

DTP recommendations related to PGx results were more likely to be classified as serious by pharmacists. Thirteen of 42 (31%) PGx DTPs were labeled as serious, while only 47 (4.6%) of the remaining 1,012 DTPs were categorized as serious, which estimated an OR of 9.20 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.50-18.85) for PGx DTPs to be classified as grade 3 or above (P < 0.0001). Statistical significance continued (P < 0.0001) with an OR of 8.45 (95% CI = 3.10-23.05) when the analysis was limited to the DTPs from the PGxMTM cohort only (Figure 3). Of the 13 PGx-DTPs labeled with grade 3 or above, 5 were DDGIs.

FIGURE 3.

DTP Seriousness

Of the 1,054 DTP recommendations, 489 were eligible for the acceptance measure. In comparison with the less serious DTPs, the serious DTP recommendations were more likely to be accepted by prescribers (OR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.00-3.84, P = 0.05) after the exclusion of the DTP recommendations for which the acceptance was unknown. When the analysis was limited to the DTP recommendations made for the PGxMTM arm, the OR of acceptance for serious DTPs was 2.39 (95% CI = 0.71-8.02, P = 0.15). The Cohen’s kappa coefficient was 0.08 (P = 0.05) and 0.14 (P = 0.15) from all the eligible DTPs and the DTPs from the PGxMTM cohort, respectively, which falls in the slight level of agreement category (Table 2).13

TABLE 2.

Seriousness of DTPs as a Surrogate for a Utility in a Prescriber’s Decision

| Status Knowna | Accept (%) | Reject (%) | OR (95% CI) | P Value | Cohen’s Kappa Coefficientb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | ||||||

| Serious DTPs | 41 | 15 (36.6) | 26 (63.4) | 1.95 (1.00-3.84) | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| Less serious DTPs | 448 | 102 (22.8) | 346 (77.2) | |||

| PGxMTM group only | ||||||

| Serious DTP | 13 | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 2.39 (0.71-8.01) | 0.15 | 0.14 |

| Less serious DTPs | 72 | 19 (26.4) | 53 (73.6) | |||

aAcceptance of 489 DTPs (of 1,054 total) was known. Analysis included the 489 DTPs.

bKappa: inter-rater reliability, agreement between serious DTPs (i.e., grade 3 or above) flagged by pharmacists and acceptance of DTPs in a prescription.

CDST = clinical decision support tool; CI = confidence interval; DTPs = drug therapy problems; MTM = medical therapy management; OR = odds ratio; PGx = pharmacogenetics;

PGxMTM = MTM supported by PGx information and CDST.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the potential clinical utility of a novel platform of PGx testing combined with a CDST for polypharmacy patients in an MTM setting. Although there was only a slight nonstatistical trend toward an increased number of DTPs identified per patient across the 3 intervention arms, the proportion of serious DTPs identified and acceptance rate of recommendations for future avoidance were significantly higher in patients undergoing PGx testing. Furthermore, pharmacists were able to identify more serious DTPs when the decision was supported by the PGx results in comparison with the identified DTPs in the absence of the patient-specific PGx information, meaning that genetic profiles of patients help capture potential problems that would not be identified through standard MTM programs. The increased seriousness of DTPs identified through the utilization of PGx test results demonstrates a patient-safety opportunity that is currently being overlooked in many MTM programs.

Over the past decade, studies have increasingly investigated the relationship between individual PGx targets and associated medications, commonly referred to as drug-gene pairs.14,15 Previous studies have also assessed the utility of PGx in multiple settings. For example, a recent comparative study demonstrated that genetic profiles of cytochrome enzymes in elderly patients may reduce the hospitalization rate by 6.3% within 4 months, promising potential for health care cost savings.9 In Caucasian polypharmacy patients aged 50 years or older being managed in a home health setting, pharmacogenetic testing supported by a CDST significantly reduced the rate of hospitalization with a relative risk of 0.48.16 However, evaluation of MTM for outpatient polypharmacy patients that incorporates PGx has been limited, likely due to lack of reimbursement for PGx testing costs as well as the lack of PGx information in standard drug information tools traditionally used by MTM pharmacists.17 Using the data collected from a randomized controlled study, this study demonstrates the usefulness of PGx in an MTM setting in that it identifies more serious drug therapy problems as compared to standard MTM programs. To determine clinical utility, a test has to improve patient outcomes in clinical practice, which is only achievable with the prescriber’s acceptance of a pharmacist’s recommendation in the MTM setting.18 Whether a test result is actionable is a primary driver for payer reimbursement and is a challenge in the personalized medicine and health information technology sectors.19 This study demonstrates that pharmacists provided actionable medication recommendations when assisted by PGx information. When recommendations were associated with more serious DTPs, there was a modest increase in the acceptance of recommendations as indicated by changes in future prescribing. This result supports the American Society of Health System Pharmacy’s statement on the pharmacist’s role in clinical pharmacogenetics in that pharmacists are well positioned to assess drug-related genetic profiles and provide this information to health care providers to support improved outcomes at potentially lower overall costs.20 Furthermore, a drug change in response to a pharmacist’s recommendation may correlate with a significant decrease in the overall medication costs per patient. The modest level of acceptance observed in this study has the potential to support a payer’s decision in favor an MTM service incorporating pharmacogenetics.21

Although DDGIs have always been prevalent, they are now becoming more recognized and are not captured by most clinical decision support tools used today. A recent study noted that 54.6% of patients taking medications that interacted with genes were also taking medications that affected the same enzyme, a phenomenon referred to as phenoconversion.22 Another study found that around 20% of drug interactions were DDGIs, which are often missed without CDST.8 In this study, pharmacists were able to address 13 potential DDGIs from PGx results by using CDST, which accounted for 7.2% of all DTPs from the PGxMTM arm. Due to the small number, the analyses for seriousness and acceptance of DTPs were not broken down into interaction type groups, DDIs, DGIs or DDGIs. A future study evaluating the utility of CDSTs that can identify genetic interactions compounded by multiple drugs, that is, phenoconversion, is warranted.

Although PGx helped to identify serious DTPs and was associated with an increase in the utility of DTP recommendations, the overall rate of acceptance across all DTPs remained less than 30%. It is surmised from this result that prescribers, specifically in the absence of proper PGx education, are conservative in accepting DTPs based on genotype.23-25 PGx may further complicate the clinical decision when the predicted ADR was not observed while the patient was on the treatment or when multiple DTP recommendations conflict each other. In addition, PGx recommendation has a potential to increase the treatment cost with a marginal benefit, which also leads to physicians being cautious about incorporating predicted outcomes before the outcomes are observed. Future precision medicine research will need to focus on a decision algorithm to help clinicians integrate bioinformatics that have a potential to conflict with traditional medical decisions.

Reimbursement for PGx testing will require increased levels of evidence to support the clinical and economic benefit versus no testing. In a previous study, the cost of the test was estimated at $914.9 However, the test only needs to be done 1 time and may provide important information towards clinical decision making for years to come. Thus, the cumulative savings from avoided consequences of adverse events or lack of effect because of over or under drug dosing may far outweigh this initial investment in the test. Continued information on the clinical utility and value of PGx testing will inform future continued information on the clinical utility, and value of PGx testing will inform the evolving future policies on coverage of PGx testing.26

Limitations

Limitations of this study must be noted along with our findings. First, baseline characteristics of patients who were allocated to the non-PGx arms or who dropped out from the PGxMTM cohort may be systematically different from those who provided the buccal swab sample, specifically in baseline ADRs and gender distribution, despite lack of statistical significance in the current study. However, the GLM approach confirmed that the difference in baseline characteristics across the study arms was not a significant confounder in the exposure-outcome association. Further, the seriousness of DTPs evaluated for each recommendation, not for each patient, was independent from the patient factors and therefore is not a potential source of bias in our conclusions.

Second, the retrospective nature in capturing the rate of DTP recommendation acceptance through pharmacy claims data was also a limitation. Investigators were unable to assess the recommendation acceptance rate for more than 50% of all DTPs primarily because not all recommendations were accurately captured from the data source (e.g., nonprescription drug recommendations and drug monitoring recommendations). Further, whether there was an actual difference in medical encounters across the 3 arms could not be assessed solely through the pharmacy claims data source used.

Finally, the lack of prescriber education related to the PGxMTM recommendations should be considered. Most prescribers currently do not use PGx in daily practice so may be reluctant to accept the validity of such a recommendation at face value. Ultimately, assessing clinical utility is limited by the level of familiarity of the prescribers receiving MTM recommendations. PGx familiarity at the time of this study was rather low and, as a result, may have affected the level of acceptance of DTP recommendations.

Conclusions

Despite a lack of prescriber familiarity with PGx and an inability to confidently capture all DTP recommendation acceptances, this study demonstrates a strong potential for future use of PGx and CDST in MTM services for polypharmacy patients. Future investigation into the application of PGx testing within MTM services will need to refine the methods used to detect acceptance rates, which may be accomplished in a more integrated health system. Future studies will also need to investigate the clinical utility for prescribers who have greater familiarity with the clinical use of pharmacogenetic information and the clinical value towards payer reimbursement decisions.

Acknowledgments

Annie Cheng, a student of the School of Pharmacy at the University of California, San Francisco, and an outcomes research intern at the Pharmacotherapy Outcomes Research Center, University of Utah, compiled general information on which the introduction of this manuscript was written. Also, Ranjit Thirumaran, Nicolas Moyer, and Kristine Ashcraft, all employees of YouScript, collaborated with the authors on the study design, data collection, and manuscript draft.

APPENDIX A. DTP Examples from 2 Patients Assigned to the PGx Arm

| Patient ID | Conditions | Medications | DTP Recommendation | Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | Hyperlipidemia Edema Hypokalemia Type 2 diabetes Angina CHF |

Aspirin 81 mg Atorvastatin 80 mg Clopidogrel 75 mg Furosemide 80 mg Sitagliptin (Januvia, Merck) 100 mg Potassium 20 mEq Metoprolol tartrate 25 mg Canagliflozin (Invokana, Janssen) 300 mg Vitamin D3 1000 IU Vitamin C 500 mg Multivitamin Glucosamine and chondroitin Dulaglutide (Trulicity, Lilly) 0.75mg/0.5mL Nitrostat 0.4 mg |

Switch from dulaglutide and canagliflozin (Tier 3) to insulin glargine injection (Lantus, Sanofi) 100 U/mL (Tier 2) for cost savings | 1 |

| Switch from metoprolol tartrate 25 mg twice daily to metoprolol succinate 50 mg due to CHF | 3 | |||

| Start lisinopril 5 mg once daily due to CHF and type 2 diabetes | 4 | |||

| Assess patient-reported burning upon urination and trouble initiating urination | 2 | |||

| Start gabapentin 300 mg once daily; titrate to lowest effective dose due to patient-reported diabetic neuropathy | 2 | |||

| Switch from vitamin D 1000 IU once daily to calcium 600 mg + vitamin D 400 IU twice daily for prevention of osteoporosis | 1 | |||

| 17 | Hyperlipidemia Depression Anxiety Type 2 diabetes Hypertension Insomnia GERD |

Atorvastatin Citalopram Clonazepam Insulin lispro injection (Humalog, Lilly) Insulin glargine injection Lisinopril Mirtazapine Omeprazole Venlafaxine Multivitamin Aspirin Zinc Calcium + d3 Vitamin E Cinnamon Hydrocodone bitartrate/acetaminophen (Norco, Actavis Pharma) |

Re-evaluate need for mirtazapine due to xerostomia and Beers Criteria recommendation | 2 |

| Discontinue citalopram to avoid QT prolongation | 2 | |||

| Evaluate possibility of switching to oral diabetic therapy due to cost issues | 1 | |||

| Increase atorvastatin from 10 mg to 40 mg to improve therapy | 2 | |||

| PGx recommendation: Discontinue citalopram 20 mg and initiate sertraline 50 mg to avoid adverse events; DDGI involves citalopram, omeprazole, and CYP2C19 | 3 |

CHF = congestive heart failure; CYP = cytochrome P; DDGI = drug-drug-gene interactions; DTP = drug treatment problems; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; ID = identification; PGx = pharmacogenetic.

References

- 1.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47(3):533-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hampton LM, Daubresse M, Chang HY, Alexander GC, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits by adults for psychiatric medication adverse events. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(9):1006-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams BR, Kim J. Medication use and prescribing considerations for elderly patients. Dent Clin North Am. 2005;49(2):411-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elliott RA, Woodward MC. Medication-related problems in patients referred to aged care and memory clinics at a tertiary care hospital. Australas J Ageing. 2011;30(3):124-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ai AL, Carretta H, Beitsch LM, Watson L, Munn J, Mehriary S. Medication therapy management programs: promises and pitfalls. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(12):1162-82. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.12.1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Pharmacists Association . APhA MTM Central: what is medication therapy management? 2015. Available at: http://pharmacistsprovidecare.com/mtm. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- 7.Godman B, Finlayson AE, Cheema PK, et al. Personalizing health care: feasibility and future implications. BMC Med. 2013;11:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verbeurgt P, Mamiya T, Oesterheld J. How common are drug and gene interactions? Prevalence in a sample of 1,143 patients with CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 genotyping. Pharmacogenomics. 2014;15(5):655-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brixner D, Biltaji E, Bress A, et al. The effect of pharmacogenetic profiling with a clinical decision support tool on healthcare resource utilization and estimated costs in the elderly exposed to polypharmacy. J Med Econ. 2016;19(3):213-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . Medicare drug benefit and C & D data group. CY 2016 medication therapy management program guidance and submission instructions. April 7, 2015. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/Memo-Contract-Year-2016-Medication-Therapy-Management-MTM-Program-Submission-v-040715.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2018.

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Cancer Insitute . Common terminology criteria for adverse events. Version 4.0. Revised June 14, 2010. Available at: https://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2018.

- 12.Somers A, Robays H, De Paepe P, Van Maele G, Perehudoff K, Petrovic M. Evaluation of clinical pharmacist recommendations in the geriatric ward of a Belgian university hospital. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:703-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahabi P, Dube MP. Cardiovascular pharmacogenomics; state of current knowledge and implementation in practice. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:772-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez V, Salavert A, Espadaler J, et al. ; AB-GEN Collaborative Group. Efficacy of prospective pharmacogenetic testing in the treatment of major depressive disorder: results of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott LS, Henderson JC, Neradilek MB, Moyer NA, Ashcraft KC, Thirumaran RK. Clinical impact of pharmacogenetic profiling with a clinical decision support tool in polypharmacy home health patients: a prospective pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0170905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haga SB, Allen LaPointe NM, Moaddeb J.. Challenges to integrating pharmacogenetic testing into medication therapy management. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(4):346-52. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.4.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canestaro WJ, Pritchard DE, Garrison LP, Dubois R, Veenstra DL. Improving the efficiency and quality of the value assessment process for companion diagnostic tests: the Companion test Assessment Tool (CAT). J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(8):700-12. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.8.700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faulkner E, Annemans L, Garrison L, et al. ; Personalized Medicine Development and Reimbursement Working Group. Challenges in the development and reimbursement of personalized medicine-payer and manufacturer perspectives and implications for health economics and outcomes research: a report of the ISPOR personalized medicine special interest group. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1162-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ASHP statement on the pharmacist’s role in clinical pharmacogenomics . Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(7):579-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugarman EA, Cullors A, Centeno J, Taylor D. Contribution of pharmacogenetic testing to modeled medication change recommendations in a long-term care population with polypharmacy. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(12):929-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blagec K, Kuch W, Samwald M. The importance of gene-drug-drug-interactions in pharmacogenomics decision support: an analysis based on Austrian claims data. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;236:121-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selkirk CG, Weissman SM, Anderson A, Hulick PJ. Physicians’ preparedness for integration of genomic and pharmacogenetic testing into practice within a major healthcare system. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(3):219-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogausch A, Prause D, Schallenberg A, Brockmöller J, Himmel W. Patients’ and physicians’ perspectives on pharmacogenetic testing. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7(1):49-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haga SB, Burke W, Ginsburg GS, Mills R, Agans R. Primary care physicians’ knowledge of and experience with pharmacogenetic testing. Clin Genet. 2012;82(4):388-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips KA. Evolving payer coverage policies on genomic sequencing tests: beginning of the end or end of the beginning? JAMA. 2018;319(23):2379-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]