Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Oral anticoagulation such as warfarin and dabigatran is indicated for atrial fibrillation (AF) patients at risk of ischemic stroke. Dabigatran etexilate was developed to address the limitations of warfarin, including the need for regular blood monitoring, which has the potential to lead to higher health care resource use, particularly in hospitalized patients.

OBJECTIVE:

To evaluate whether hospitalization cost, length of hospital stay (LOS), likelihood of readmission within 30 days, and cost of readmissions differed across inpatient encounters among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients that were newly diagnosed and newly treated with either dabigatran or warfarin.

METHODS:

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using IMS Health’s Charge Detail Master (CDM) database. Hospitalizations were identified based on a primary or secondary AF diagnosis, dabigatran or warfarin use, and a discharge date from January 2011 through March 2012. The identified patients without valvular procedures and transient AF were required to have a minimum of 12 months of pharmacy and private practitioner records prior to the inpatient encounter to ensure that they were newly treated on dabigatran or warfarin. Propensity score matching was used to balance baseline characteristics between treatment cohorts. Outcomes assessed were LOS, 30-day readmissions, and costs. Because individual patients could have more than 1 hospital observation, generalized estimating equations (GEE) with a gamma distribution (log link) were used for the analysis of continuous outcome measures (e.g., LOS and costs) and a binominal distribution for dichotomous outcomes (hospital readmissions).

RESULTS:

Two cohorts were propensity score matched (1:2) on demographic and clinical characteristics. The dabigatran cohort included 646 hospitalizations, and the warfarin cohort included 1,292 hospitalizations. Hospitalizations were on average 13% shorter (4.8 vs. 5.5 days, P < 0.001) and cost 12% less ($14,794 vs. $16,826, P = 0.007) when dabigatran was used versus warfarin. No differences in 30-day readmissions were observed.

CONCLUSIONS:

Hospital encounters among newly diagnosed NVAF patients during which warfarin was initiated had longer lengths of stay and incurred higher costs than those during which dabigatran was initiated.

What is already known about this subject

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and other payers are increasingly focused on reducing length of stay and readmission rates to improve quality of care and reduce cost.

Warfarin has been the standard therapy for stroke prevention in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients but poses several clinical and administrative challenges in the management of these patients over time.

What this study adds

This study used a geographically diverse sample of hospitalization encounters among newly diagnosed and newly treated NVAF patients on warfarin or dabigatran.

Hospitalizations of NVAF patients newly diagnosed and started on treatment with dabigatran etexilate had shorter hospital stays and incurred lower total inpatient care costs than those patients initiated on warfarin.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) poses a substantial health care burden.1-5 Since the risk of AF increases with age, the prevalence of the disease and costs of treatment in Western countries are projected to increase with the aging population.6 In hospitalized patients, the presence of AF is a significant driver of hospital cost.3 It has become increasingly important for decision makers to understand the health care utilization and costs that are associated with anticoagulation treatment options as their use relates to hospitalization and readmissions for better management of AF patients.

Anticoagulation is indicated for AF patients with moderate to high risk of ischemic stroke. Warfarin is an oral anticoagulant (OAC) therapy that has been shown to be effective in reducing the risk of stroke.7 It can be difficult to bring levels of warfarin to within therapeutic range and to maintain those levels, making international normalized ratio (INR) monitoring necessary.8 The limitations of warfarin are well known; in particular, the fluctuating levels of anticoagulation with a warfarin regimen may contribute to undertreatment.9,10 New OAC therapies, such as dabigatran etexilate, have been developed to address the limitations of warfarin therapy.

Dabigatran etexilate is approved for the reduction of risk of stroke and systemic embolism in nonvalvular AF (NVAF).11 Dabigatran does not interact with cytochrome P450 pathway drugs, and there is no requirement for INR monitoring. In a large, randomized phase III clinical study,12,13 rates of stroke, systemic embolism, and intracranial bleeding were significantly lower for dabigatran 150 milligrams (mg) twice daily compared with warfarin after a median 2-year follow-up. Similar efficacy was observed among patients new to warfarin treatment and with prior warfarin experience.14,15 Real-world clinical practice studies have shown that mortality, intracranial bleeding, and pulmonary embolism are lower with dabigatran compared with warfarin.16

Given the guidance from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), there are several national and regional initiatives underway to reduce unplanned all-cause readmissions.17 With an increasing incidence of NVAF and a growing interest in improving quality of care across the continuum of health care settings, it is pertinent for payers and providers to understand the association between OAC treatment choice on length of stay (LOS), readmission rates, and costs. There are currently no known published real-world studies comparing U.S. hospital utilization in newly diagnosed NVAF patients newly treated with warfarin or dabigatran. The current study assessed total inpatient care cost, LOS, 30-day readmissions, and associated readmission costs among newly diagnosed NVAF patients who were newly treated with dabigatran or warfarin.

Methods

Data Sources

We identified hospitalizations from a nationwide hospital operational records database (IMS Health Charge Detail Master) consisting of approximately 400 facilities in the United States. Cost-to-charge ratios submitted to CMS were used to approximate hospitals’ average actual costs of goods and services, which may be below or above the amounts charged for a specific item. Hospital records and pharmacy claims (National Council for Prescription Drug Programs) data were used to determine patients’ prior exposure to study medications and medications related to major bleed risk. Hospital records and private practitioner claims (CMS-1500) data were used to classify inpatients with respect to history of AF diagnosis, prior cardiac valve procedures, comorbid conditions, and stroke or major bleed risks. Patient-level data in this study were de-identified. All databases utilized in this study were certified as being compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; therefore institutional review board approval was not necessary.

Study Sample Identification

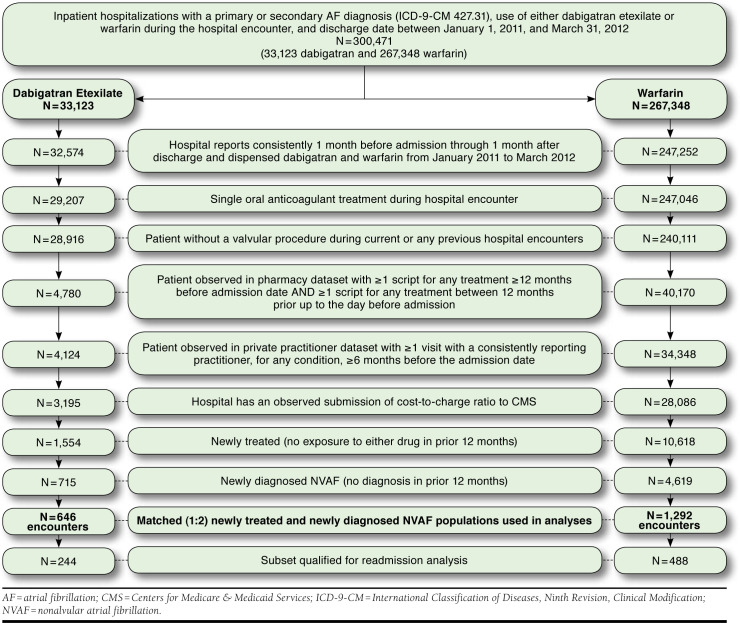

The study sample consisted of all hospitalizations with AF as a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] 427.31, atrial fibrillation), a discharge date between January 2011 and March 2012 and the use of either warfarin or dabigatran (see Appendix A for drug classification terms, available in online article). The earliest hospitalization identified became the index encounter. Ultimately, only encounters for patients newly diagnosed with AF and newly treated with either warfarin or dabigatran, based on observed data during the 12 months prior to admission, were included. The study design schematic and outcomes measured are shown in Figure 1. Figure 2 shows the selection criteria for the study samples.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic Representation of Study Design

FIGURE 2.

Flowchart Describing the Process of Sample Selection (Inclusion/Exclusion)

Hospitals reporting consistently between 1 month prior to admission through 1 month after discharge and that dispensed dabigatran and warfarin were included. Encounters recording multiple OAC treatments or for patients with concurrent or prior cardiac valve procedures (ICD-9-CM procedure codes 35.20, 35.22, 35.24, 35.26, and 35.28 or ICD-9-CM 394.0, mitral stenosis; history back to 2001) were excluded to avoid confounding of the outcomes assessment. To ensure inclusion of prior medication and diagnostic history, only encounters for patients with observable pharmacy database activity within the 12 months prior to admission and more than 12 months before admission, as well as observable private practitioner database activity more than 6 months prior to admission were included. Hospitals also had to have submissions of their cost-to-charge ratios to CMS.

The subset of index encounters assessed for 30-day readmissions, adhering to the CMS Hospital Readmission Reduction Program inclusion criteria, were required to have AF as the primary diagnosis and not itself be a 30-day readmission from any prior hospitalization.18 Additionally, the subset of encounters were limited to those where the patient was alive upon discharge and was discharged home or to another residence but not to an acute care facility. To assess broader impact, the analysis was not limited to those aged ≥ 65 years. The dabigatran and warfarin inpatient encounters were matched and further adjusted using multivariate regression.

Study Cohort Matching

Propensity score matching was used to minimize the potential impact of selection bias with matching hospital encounters in the dabigatran cohort with those from the warfarin cohort that shared similar demographic and clinical characteristics.19 Each hospital encounter in the dabigatran cohort was matched, without replacement, using a 1:2 “nearest neighbor matching” technique, with a caliper of 0.20 of the standard deviation of the estimated logit of the propensity score.20,21 During matching, dabigatran and warfarin encounters were required to either both qualify for the readmission analysis or both not qualify to ensure balance among the subset. The propensity score was computed using a logistic regression model that adjusted for covariates including age, gender, payer, diagnoses listed within a modified Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index22; CHADS2 stroke risk (1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, aged ≥ 75 years, and diabetes mellitus and 2 points for transient ischemic attack or stroke); HAS-BLED major bleed risk (1 point each for current or prior hypertension, kidney disease, liver disease, stroke, major bleeding event, or having a condition that predisposes to bleeding, medication use that predisposes to risk of bleeding, abnormal INR, alcohol abuse, and aged > 65 years); number of prior hospital encounters; hospital characteristics; and geography. The CHADS2 calculator is widely used in the United States to estimate stroke risk.23,24 The HAS-BLED scoring system has proven predictive of intracranial bleed and of bleeding during bridging and has been validated against other risk scores.25-27

The success of propensity score matching was assessed by comparing the prematch and postmatch balance of identified covariates. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The Welch’s t-test was used for differences in means, assuming unequal variances. A standardized difference between the 2 cohorts (mean difference expressed as a percentage of the average standard deviation of the variable’s distribution across the dabigatran and warfarin cohorts) of < 10 was considered indicative of good balance.19,28 Propensity score matching was performed using The Comprehensive R Archive Network and the MatchIt package.29

Outcome Measures

The inpatient encounters were assessed for total inpatient care cost, LOS, likelihood of readmission within 30 days, and the total cost of readmissions within 30 days. Costs were computed by multiplying the charges by the inpatient cost-to-charge ratio reported to CMS.

Multivariate Analysis

To account for non-normal distribution of outcomes and possible correlation between observations within the same hospital (clusters) across the study period and to further adjust for covariates that remained statistically different after matching, a generalized linear model (GLM) with a gamma distribution (log link) for analysis of LOS, hospital cost, and readmission cost, and binominal distribution for hospital readmission was used based on generalized estimating equations (GEE) methodology. Analyses were performed using The Comprehensive R Archive Network and an a priori statistical significance level of 0.05. The GLM fitted by GEE was conducted using the geepack package.30

Results

Study Samples

There were 33,123 inpatient encounters in the dabigatran cohort and 267,348 in the warfarin cohort for which 3,195 and 28,086 encounters, respectively, met inclusion and exclusion criteria (Figure 2). The available unmatched subset of encounters for newly treated/newly diagnosed patients included 715 hospitalizations in the dabigatran cohort and 4,619 in the warfarin cohort. Matched samples included 646 hospitalizations in the dabigatran cohort and 1,292 in the warfarin cohort. Within the matched sample, there were 244 hospitalizations in the dabigatran cohort and 488 in the warfarin cohort that met the study criteria for assessment of readmissions within 30 days.

Demographics and Characteristics

Table 1 shows the pre- and postmatched characteristics of hospitalized patients by cohort. The postmatch cohorts were generally well balanced. Postmatch demographic characteristics including gender, age, and comorbidity covariates demonstrated nonsignificant differences at P < 0.05. The percentage of postmatched hospitalizations with a patient history of prior thromboembolism or prior coronary artery disease (see Appendix B for ICD-9-CM codes for these and other referenced diagnoses, available in online article) had persistent variance at P < 0.05 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Hospital Characteristics for Matched Cohorts

| Dabigatran Etexilate | Warfarin | P Valuea | Dabigatran Etexilate | Warfarin | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of unique hospitalizations | 715 | 4,619 | 646 | 1,292 | ||

| Characteristics of Patients, n (%) | Prematch | Postmatch | ||||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean [SD] | 70.7 [11.7] | 73.1 [10.6] | < 0.001 | 71.7 [11.4] | 72.1 [10.9] | 0.534 |

| ≤ 59 | 109 (15) | 527 (11) | < 0.001 | 81 (13) | 168 (13) | 0.284 |

| 60-64 | 69 (10) | 391 (9) | 53 (8) | 130 (10) | ||

| 65-69 | 115 (16) | 542 (12) | 102 (16) | 157 (12) | ||

| 70-74 | 121 (17) | 682 (15) | 115 (18) | 218 (17) | ||

| 75-79 | 106 (15) | 909 (20) | 103 (16) | 223 (17) | ||

| 80-84 | 111 (16) | 862 (19) | 110 (17) | 212 (16) | ||

| 85+ | 84 (12) | 706 (15) | 82 (13) | 184 (14) | ||

| Female | 344 (48) | 2,301 (50) | 0.396 | 323 (50) | 678 (53) | 0.304 |

| Payer type | ||||||

| Commercial | 192 (27) | 899 (20) | < 0.001 | 151 (23) | 276 (21) | 0.205 |

| Medicare | 484 (68) | 3,340 (72) | 461 (71) | 925 (72) | ||

| Medicaid | 23 (3) | 211 (5) | 20 (3) | 41 (3) | ||

| Other/unspecified | 16 (2) | 169 (4) | 14 (2) | 50 (4) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation was primary diagnosis (vs. secondary diagnosis) | 317 (44) | 1,000 (22) | < 0.001 | 255 (40) | 522 (40) | 0.694 |

| No prior atrial fibrillation diagnosis | 715 (100) | 4,619 (100) | NA | 646 (100) | 1,292 (100) | NA |

| Secondary drug (bridging agent) | ||||||

| None (product only) | 211 (30) | 927 (20) | < 0.001 | 167 (26) | 307 (24) | 0.313 |

| With any bridging agent (LMWH/PS and/or UFH) | 504 (70) | 3,692 (80) | 479 (74) | 985 (76) | ||

| Comorbidities during prior 12 months | ||||||

| At least 1 condition as defined by Charlson Comorbidity Index | 588 (82) | 4,176 (90) | < 0.001 | 552 (85) | 1,120 (87) | 0.455 |

| AIDS/HIV | 1 (0) | 17 (0) | b | 1 (0) | 5 (0) | b |

| Cancer | 111 (16) | 902 (20) | 0.011 | 107 (17) | 237 (18) | 0.334 |

| Congestive heart failure | 254 (36) | 2,122 (46) | < 0.001 | 239 (37) | 489 (38) | 0.715 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 224 (31) | 1,718 (37) | 0.002 | 208 (32) | 469 (36) | 0.074 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 149 (21) | 1,126 (24) | 0.039 | 143 (22) | 282 (22) | 0.877 |

| Dementia | 23 (3) | 256 (6) | 0.009 | 22 (3) | 65 (5) | 0.103 |

| Diabetes (with or without complication) | 234 (33) | 1,816 (39) | 0.001 | 228 (35) | 421 (33) | 0.234 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 11 (2) | 136 (3) | 0.034 | 11 (2) | 29 (2) | 0.429 |

| Myocardial infarction | 110 (15) | 854 (19) | 0.045 | 105 (16) | 194 (15) | 0.477 |

| Liver disease (mild through severe) | 22 (3) | 143 (3) | 0.978 | 20 (3) | 32 (3) | 0.426 |

| Paraplegia and hemiplegia | 19 (3) | 186 (4) | 0.076 | 19 (3) | 39 (3) | 0.925 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 15 (2) | 100 (2) | 0.908 | 14 (2) | 27 (2) | 0.911 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 79 (11) | 682 (15) | 0.008 | 79 (12) | 167 (13) | 0.664 |

| Renal disease | 111 (16) | 1,260 (27) | < 0.001 | 110 (17) | 205 (16) | 0.514 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 40 (6) | 268 (6) | 0.825 | 40 (6) | 86 (7) | 0.696 |

| At least 1 condition from stroke risk calculations | 673 (94) | 4,478 (97) | < 0.001 | 613 (95) | 1,228 (95) | 0.883 |

| Congestive heart failure | 255 (36) | 2,107 (46) | < 0.001 | 240 (37) | 483 (37) | 0.921 |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 55 (8) | 526 (11) | 0.003 | 52 (8) | 115 (9) | 0.529 |

| Hypertension | 608 (85) | 4,059 (88) | 0.033 | 554 (86) | 1,118 (87) | 0.641 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 234 (33) | 1,824 (40) | 0.001 | 228 (35) | 424 (33) | 0.277 |

| Stroke/transient ischemic | 190 (27) | 1,336 (29) | 0.196 | 182 (28) | 336 (26) | 0.309 |

| Thromboembolism | 17 (2) | 939 (20) | < 0.001 | 17 (3) | 99 (8) | < 0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 110 (15) | 854 (19) | 0.045 | 105 (16) | 194 (15) | 0.477 |

| Coronary artery disease | 276 (39) | 2,277 (49) | < 0.001 | 260 (40) | 581 (45) | 0.048 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 43 (6) | 417 (9) | 0.008 | 41 (6) | 94 (7) | 0.449 |

| Risk for stroke | ||||||

| Mean CHADS2 scorec [SD] | 2.5 [1.4] | 2.8 [1.4] | < 0.001 | 2.6 [1.4] | 2.6 [1.3] | 0.590 |

| Mean CHADS2-VASc scored [SD] | 4.2 [1.9] | 5.0 [1.8] | < 0.001 | 4.4 [1.8] | 4.5 [1.8] | 0.266 |

| Characteristics of Patients, n (%) | Prematch | Postmatch | ||||

| Risk for major bleed, mean HAS-BLED scoree [SD] | 3.0 [1.2] | 3.4 [1.2] | < 0.001 | 3.1 [1.1] | 3.0 [1.1] | 0.092 |

| Mean number of prior hospitalizations, all-cause, within 12 months [SD] | 0.3 [0.7] | 0.4 [0.9] | < 0.001 | 0.3 [0.8] | 0.3 [0.7] | 0.514 |

| Within study sample, which hospitalization is this for patient? | ||||||

| 1st | 703 (98) | 4,400 (95) | 0.002 | 635 (98) | 1,237 (96) | 0.011 |

| 2nd | 12 (2) | 199 (4) | 11 (2) | 51 (4) | ||

| 3rd | 0 | 19 (0) | 0 | 4 (0) | ||

| 4th | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Characteristics of Hospitalization (unadjusted) | Prematch | Postmatch | ||||

| Mean length of stay [SD] | 4.9 [4.9] | 7.5 [6.8] | < 0.001 | 5.2 [5.1] | 6.1 [5.9] | < 0.001 |

| Mean days in ICU/CCU [SD] | 1.0 [2.6] | 2.0 [4.2] | < 0.001 | 1.1 [2.7] | 1.6 [3.6] | 0.001 |

| Mean unique days on drug [SD] | 2.9 [2.8] | 3.8 [3.3] | < 0.001 | 3.0 [2.9] | 3.4 [3.1] | 0.005 |

| Mean unique days on bridging agentf [SD] | 2.1 [3.0] | 4.0 [4.5] | < 0.001 | 2.2 [3.1] | 3.2 [3.7] | < 0.001 |

| Identified as “index” encounter for readmission subset analysis,g n (%) | 303 (42) | 934 (20) | < 0.001 | 244 (38) | 488 (38) | 1.000 |

| Characteristics of Hospitals, n (%) | Prematch | Postmatch | ||||

| U.S. Census divisions | ||||||

| New England | 3 (0) | 112 (2) | < 0.001 | 3 (1) | 12 (1) | 0.452 |

| Middle Atlantic | 79 (11) | 496 (11) | 70 (11) | 122 (9) | ||

| East North Central | 41 (6) | 291 (6) | 39 (6) | 83 (6) | ||

| West North Central | 55 (8) | 569 (12) | 55 (9) | 84 (7) | ||

| South Atlantic | 265 (37) | 1,505 (33) | 239 (37) | 476 (37) | ||

| East South Central | 45 (6) | 267 (6) | 43 (7) | 93 (7) | ||

| West South Central | 103 (14) | 505 (11) | 87 (14) | 184 (14) | ||

| Mountain | 22 (3) | 219 (5) | 22 (3) | 32 (3) | ||

| Pacific | 102 (14) | 655 (14) | 88 (14) | 206 (16) | ||

| Number of beds | ||||||

| 1-199 | 164 (23) | 1,035 (22) | < 0.001 | 148 (23) | 289 (22) | 0.214 |

| 200-299 | 143 (20) | 689 (15) | 117 (18) | 208 (16) | ||

| 300-499 | 240 (34) | 1,824 (40) | 226 (35) | 508 (39) | ||

| 500+ | 119 (17) | 580 (13) | 107 (17) | 205 (16) | ||

| Unknown | 49 (7) | 491 (11) | 48 (7) | 82 (6) | ||

| Location | ||||||

| Urban | 633 (89) | 3,841 (83) | 0.001 | 567 (88) | 1,143 (89) | 0.636 |

| Rural | 33 (5) | 287 (6) | 31 (5) | 67 (5) | ||

| Unknown | 49 (7) | 491 (11) | 48 (7) | 82 (6) | ||

| Academic (vs. community) | 281 (39) | 1,950 (42) | 0.141 | 265 (41) | 556 (43) | 0.398 |

aStatistical testing at alpha = 0.05 level. Chi-square test for categorical variables. Welch 2 sample t-test for differences in means, assuming unequal variances.

bIndicates that at least 1 cell had n < 5, so statistical testing could not be confidently preformed.

cOne point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, and diabetes mellitus; 2 points for transient ischemic attack or stroke.

dOne point each for congestive heart failure or left ventricular systolic dysfunction; hypertension; diabetes mellitus; vascular disease (inclusive of coronary artery disease, pulmonary artery disease, or myocardial infarction); female gender; age between 65 and 74 years; 2 points each for transient ischemic attack or stroke or thromboembolism and age ≥ 75 years.

eOne point each for current or prior hypertension; impaired kidney function (i.e., kidney disease); impaired liver function (i.e., liver disease); stroke, major bleeding event, or having condition that predisposes (i.e., bleeding diathesis); medication use that predisposes to risk of bleeding; abnormal INR (low detection rates in these data); alcohol abuse (low detection rates in these data); and age > 65 years.

fA bridging agent was considered as used regardless of the sequence of the bridging agent and the study drug during the encounter.

gThis was an exact match criteria in the propensity score matching.

AF = atrial fibrillation; AIDS/HIV = acquired immune deficiency syndrome/human immunodeficiency virus; ICU/CCU = intensive care unit/critical care unit; INR = international normalized ratio; LMWH/PS = low molecular weight heparin/pentasaccharide; NA = not applicable; SD = standard deviation; UFH = unfractionated heparin.

Kernel density plots illustrated uniform and overlapping densities postmatching (data not shown). Standardized difference for all covariates used for propensity matching was < 10% after matching (data not shown).

The postmatched encounters had a mean patient age of 72 years at baseline (P = 0.534; 21% of dabigatran and 23% of warfarin patients were aged < 65 years). The female-to-male balance was 50% to 50% in the dabigatran cohort and 53% to 47% in the warfarin cohort (P = 0.304). Populations were predominantly composed of encounters from the southern region of the United States, which is the largest U.S. census region. In comparison with benchmark census data of nonfederal and nonstate U.S. hospital admissions by geographic region for the most recent annual reported numbers to their respective state health departments,31 our study’s representation of inpatient admissions, while balanced within the study, is more heavily weighted towards the South (58% vs. 39%) and slightly underrepresentative of the Northeast and Midwest (11% vs. 19% and 13% vs. 23%, respectively). This study’s hospitals consisted primarily of urban community hospitals with up to 500 beds. Medicare was the primary payer for most study encounters (71% dabigatran and 72% warfarin).

AF was the primary diagnosis in 40% of each cohort (P = 0.694). Prevalent comorbidities among patients in both populations included hypertension (86% dabigatran; 87% warfarin; P = 0.641), coronary artery disease (40% dabigatran; 45% warfarin; P = 0.480), congestive heart failure (37% dabigatran; 38% warfarin; P = 0.715), chronic pulmonary disease (32% dabigatran; 36% warfarin; P = 0.074), diabetes mellitus (35% dabigatran; 33% warfarin; P = 0.234), and stroke/transient ischemic attack (28% dabigatran; 26% warfarin; P = 0.310). For both cohorts, the median HAS-BLED scores were 3, median CHADS2 scores were 2, and median CHA2DS2-VASc scores were 4. Bridging agents (see Appendix C for definition, available in online article) were used in 74% of encounters in the dabigatran cohort and 76% in the warfarin cohort (P = 0.313).

Hospital Length of Stay and Total Hospital Costs

After accounting for the effects of the covariates, encounters initiating with dabigatran had an adjusted average LOS 13% shorter compared with those initiating with warfarin (4.8 days vs. 5.5 days, P < 0.001; Table 2). Table 2 indicates the effect of other variables, adjusted for the influence of covariates including drug exposure, on LOS. Controlling for all the covariates (Table 3), the estimated total inpatient care costs of dabigatran-treated encounters was 12% lower than warfarin-treated encounters ($14,794 vs. $16,826, P = 0.007). Table 3 shows the effect of other variables, adjusted for the influence of covariates including drug exposure, on total inpatient care costs.

TABLE 2.

Difference in Adjusted Average Length of Stay Between Dabigatran and Warfarin Treatment Groups

| Explanatory Variables | Coefficient | Exp PEa | Standard Error | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.0325 | 2.81 | ||

| Treatment Group (reference: warfarin) | ||||

| Dabigatran etexilate | -0.1358 | 0.87 | 0.0369 | < 0.001 |

| Use of bridging agent (LMWH and/or UFH; reference: no) | 0.3816 | 1.46 | 0.0391 | < 0.001 |

| Patient age (in years) | 0.0022 | 1.00 | 0.0022 | 0.306 |

| Female (reference: male) | 0.0036 | 1.00 | 0.0380 | 0.924 |

| Payer type (reference: commercial) | ||||

| Medicare | 0.0973 | 1.10 | 0.0444 | 0.027 |

| Medicaid | 0.1468 | 1.16 | 0.0843 | 0.082 |

| Other/unspecified | 0.1725 | 1.19 | 0.2167 | 0.426 |

| AF was primary diagnosis (reference: secondary diagnosis) | -0.5547 | 0.57 | 0.0420 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities (excluding those used in stroke risk calculation) | ||||

| Cancer | -0.0659 | 0.94 | 0.0486 | 0.175 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.1919 | 1.21 | 0.0354 | < 0.001 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | 0.0513 | 1.05 | 0.0535 | 0.338 |

| Dementia | 0.1939 | 1.21 | 0.0943 | 0.040 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 0.2189 | 1.24 | 0.1033 | 0.034 |

| Liver disease (mild through severe) | 0.3476 | 1.42 | 0.1090 | 0.001 |

| Paraplegia and hemiplegia | 0.2441 | 1.28 | 0.0873 | 0.005 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0.4098 | 1.51 | 0.1174 | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.0314 | 1.03 | 0.0495 | 0.526 |

| Renal disease | 0.1404 | 1.15 | 0.0461 | 0.002 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 0.0463 | 1.05 | 0.0741 | 0.532 |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 0.0869 | 1.09 | 0.0560 | 0.120 |

| Thromboembolism | 0.1287 | 1.14 | 0.0642 | 0.045 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.0317 | 1.03 | 0.0592 | 0.592 |

| Coronary artery disease | -0.0389 | 0.96 | 0.0390 | 0.319 |

| Peripheral artery disease | -0.1227 | 0.88 | 0.0668 | 0.066 |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | -0.0659 | 0.94 | 0.0486 | 0.176 |

| CHADS2 scorec (reference: 2 [moderate risk]) | ||||

| 0-1 (low risk) | -0.0255 | 0.97 | 0.0547 | 0.641 |

| 3-6 (high risk) | 0.1341 | 1.14 | 0.0387 | 0.005 |

| HAS-BLED scored (reference: 2 [moderate risk)] | ||||

| 0-1 (low risk) | 0.0651 | 1.07 | 0.0765 | 0.397 |

| 3-9 (high risk) | 0.0099 | 1.01 | 0.0409 | 0.809 |

| Number of prior hospitalizations | 0.0562 | 1.06 | 0.0223 | 0.012 |

| Hospitalization within matched study sample (reference: 1st) | ||||

| 2nd | 0.4376 | 1.55 | 0.0889 | < 0.001 |

| 3rd or greater | 0.1201 | 1.13 | 0.2915 | 0.680 |

| Stay include time in the ICU/CCU (reference: no) | 0.2812 | 1.32 | 0.0597 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital U.S. Census divisions (reference: Pacific) | ||||

| New England | -0.2156 | 0.81 | 0.1257 | 0.086 |

| Middle Atlantic | 0.0921 | 1.10 | 0.0641 | 0.151 |

| East North Central | 0.0137 | 1.01 | 0.0693 | 0.844 |

| West North Central | -0.1916 | 0.83 | 0.0786 | 0.015 |

| South Atlantic | -0.0127 | 0.99 | 0.0557 | 0.820 |

| East South Central | -0.0975 | 0.91 | 0.1008 | 0.333 |

| West South Central | -0.0778 | 0.93 | 0.0638 | 0.223 |

| Mountain | -0.3743 | 0.69 | 0.0563 | < 0.001 |

| Hospital bed size (reference: 300-499 beds) | ||||

| 1-199 beds | -0.1069 | 0.90 | 0.0617 | 0.083 |

| 200-299 beds | 0.1354 | 1.14 | 0.0562 | 0.016 |

| 500+ beds | 0.0728 | 1.08 | 0.0506 | 0.150 |

| Hospital location (reference: rural) | ||||

| Urban | 0.0143 | 1.01 | 0.0656 | 0.828 |

| Unknown | 0.1082 | 1.11 | 0.0915 | 0.237 |

| Hospital type (reference: community) | ||||

| Academic | 0.1142 | 1.12 | 0.0498 | 0.022 |

aThe multiplicative effect of this level versus the reference level (e.g., 1.46 is interpreted as 46% longer length of stay; 0.87 as 13% shorter length of stay).

bGeneralized linear model with gamma distribution (log link), fitted by generalized estimating equations performed using The Comprehensive R Archive Network geepack package.

cOne point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, and diabetes mellitus; 2 points for transient ischemic attack or stroke.

dOne point each for current or prior hypertension; impaired kidney function (i.e., kidney disease); impaired liver function (i.e., liver disease); stroke, major bleeding event, or having condition that predisposes (i.e., bleeding diathesis); medication use that predisposes to risk of bleeding; abnormal INR (low detection rates in these data); alcohol abuse (low detection rates in these data); and age > 65 years.

AF = atrial fibrillation; Exp PE = exponentiated parameter estimate; ICU/CCU = intensive care unit/critical care unit; INR = international normalized ratio; LMWH/PS = low molecular weight heparin/pentasaccharide; UFH = unfractionated heparin.

TABLE 3.

Difference in Adjusted Total Inpatient Care Cost Between Dabigatran and Warfarin Treatment Groups

| Explanatory Variables | Coefficient | Exp PEa | Standard Error | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 10.4068 | 33,084.49 | ||

| Treatment Group (reference: warfarin) | ||||

| Dabigatran etexilate | -0.1287 | 0.88 | 0.0480 | 0.007 |

| Use of bridging agent (LMWH and/or UFH; reference: no) | 0.5371 | 1.71 | 0.0420 | < 0.001 |

| Patient age (in years) | -0.0072 | 0.99 | 0.0023 | 0.001 |

| Female (reference: male) | -0.0770 | 0.93 | 0.0418 | 0.065 |

| Payer type (reference: commercial) | ||||

| Medicare | 0.1344 | 1.14 | 0.0591 | 0.023 |

| Medicaid | 0.0625 | 1.06 | 0.1018 | 0.540 |

| Other/unspecified | -0.0725 | 0.93 | 0.2440 | 0.766 |

| AF was primary diagnosis (reference: secondary diagnosis) | -0.7836 | 0.46 | 0.0518 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities (excluding those used in stroke risk calculation) | ||||

| Cancer | -0.0021 | 1.00 | 0.0470 | 0.964 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.1654 | 1.18 | 0.0379 | < 0.001 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | -0.0060 | 0.99 | 0.0604 | 0.921 |

| Dementia | -0.0145 | 0.99 | 0.0796 | 0.856 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | -0.0133 | 0.99 | 0.1075 | 0.902 |

| Liver disease (mild through severe) | 0.2488 | 1.28 | 0.1348 | 0.065 |

| Paraplegia and hemiplegia | 0.2434 | 1.28 | 0.1142 | 0.033 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 0.5914 | 1.81 | 0.1942 | 0.002 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | -0.0532 | 0.95 | 0.0527 | 0.313 |

| Renal disease | 0.0747 | 1.08 | 0.0564 | 0.186 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 0.0581 | 1.06 | 0.0769 | 0.450 |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 0.1441 | 1.15 | 0.0787 | 0.067 |

| Thromboembolism | -0.0363 | 0.96 | 0.0785 | 0.643 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.1788 | 1.20 | 0.0649 | 0.006 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.0434 | 1.04 | 0.0467 | 0.353 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 0.0829 | 1.09 | 0.0768 | 0.281 |

| CHADS2 scorec (reference: 2 [moderate risk]) | ||||

| 0-1 (low risk) | 0.0427 | 1.04 | 0.0652 | 0.513 |

| 3-6 (high risk) | 0.1147 | 1.12 | 0.0470 | 0.015 |

| HAS-BLED scored (reference: 2 [moderate risk]) | ||||

| 0-1 (low risk) | -0.0351 | 0.97 | 0.0990 | 0.723 |

| 3-9 (high risk) | 0.0121 | 1.01 | 0.0471 | 0.798 |

| Number of prior hospitalizations | 0.0139 | 1.01 | 0.0239 | 0.562 |

| Hospitalization within matched study sample (reference: 1st) | ||||

| 2nd | -0.2307 | 0.79 | 0.0777 | 0.003 |

| 3rd or greater | 0.1400 | 1.15 | 0.3051 | 0.646 |

| Hospital U.S. Census divisions (reference: Pacific) | ||||

| New England | -0.1290 | 0.88 | 0.3531 | 0.715 |

| Middle Atlantic | -0.1393 | 0.87 | 0.1238 | 0.261 |

| East North Central | -0.5131 | 0.60 | 0.0833 | < 0.001 |

| West North Central | -0.2284 | 0.80 | 0.1551 | 0.141 |

| South Atlantic | -0.4457 | 0.64 | 0.0900 | < 0.001 |

| East South Central | -0.8217 | 0.44 | 0.1038 | < 0.001 |

| West South Central | -0.7246 | 0.48 | 0.1128 | < 0.001 |

| Mountain | -0.3108 | 0.73 | 0.0912 | 0.001 |

| Hospital bed size (reference: 300-499 beds) | ||||

| 1-199 beds | 0.0234 | 1.02 | 0.0856 | 0.785 |

| 200-299 beds | 0.1022 | 1.11 | 0.0956 | 0.285 |

| 500+ beds | 0.3108 | 1.36 | 0.0894 | 0.001 |

| Hospital location (reference: rural) | ||||

| Urban | -0.3411 | 0.71 | 0.0970 | < 0.001 |

| Unknown | 0.2487 | 1.28 | 0.1695 | 0.142 |

| Hospital type (reference: community) | ||||

| Academic | 0.1886 | 1.21 | 0.0779 | 0.016 |

aThe multiplicative effect of this level versus the reference level (e.g., 1.04 is interpreted as 4% higher total health care costs; 0.69 as 31% lower total health care costs).

bGeneralized linear model with gamma distribution (log link), fitted by generalized estimating equations performed using The Comprehensive R Archive Network geepack package.

cOne point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, and diabetes mellitus; 2 points for transient ischemic attack or stroke.

dOne point each for current or prior hypertension; impaired kidney function (i.e., kidney disease); impaired liver function (i.e., liver disease); stroke, major bleeding event, or having condition that predisposes (i.e., bleeding diathesis); medication use that predisposes to risk of bleeding; abnormal INR (low detection rates in these data); alcohol abuse (low detection rates in these data); and age > 65 years.

AF = atrial fibrillation; Exp PE = exponentiated parameter estimate; INR = international normalized ratio; LMWH/PS = low molecular weight heparin/pentasaccharide; UFH = unfractionated heparin.

Proportion of Hospital Readmissions and Costs of Readmission

A subset of encounters qualified for analysis of 30-day hospital readmissions (n = 244 in the dabigatran cohort and n = 488 in the warfarin cohort). There were 31 dabigatran and 72 warfarin index encounters with at least 1 subsequent hospitalization within 30 days from discharge. The results of the readmission analyses are presented in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Difference in Adjusted Hospital Readmission Rate Between Dabigatran and Warfarin Treatment Groups

| Explanatory Variables | Coefficient | Standard Error | P Valuea | Odds Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -2.5046 | 0.08 | ||

| Treatment Group (reference: warfarin) | ||||

| Dabigatran etexilate | -0.0129 | 0.21 | 0.951 | 0.99 |

| Use of bridging agent (LMWH and/or UFH; reference: no) | 0.3109 | 0.37 | 0.395 | 1.36 |

| Patient age (in years) | 0.0028 | 0.01 | 0.844 | 1.00 |

| Female (reference: male) | 0.4567 | 0.27 | 0.094 | 1.58 |

| Payer type (reference: commercial) | ||||

| Medicare | 0.1041 | 0.35 | 0.763 | 1.11 |

| Medicaid | 0.6944 | 0.63 | 0.269 | 2.00 |

| Other/unspecified | 0.8188 | 1.20 | 0.496 | 2.27 |

| Comorbidities (excluding those used in stroke risk calculation) | ||||

| Cancer | 0.4350 | 0.25 | 0.086 | 1.54 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.0988 | 0.23 | 0.661 | 1.10 |

| Cerebral vascular disease | -0.3507 | 0.38 | 0.350 | 0.70 |

| Dementia | 0.0207 | 0.61 | 0.973 | 1.02 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | -0.2988 | 1.13 | 0.792 | 0.74 |

| Liver disease (mild through severe) | -1.0234 | 1.10 | 0.354 | 0.36 |

| Paraplegia and hemiplegia | 1.4393 | 1.13 | 0.204 | 4.22 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | -9.2118 | 1.28 | < 0.001 | < 0.01 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | -0.0735 | 0.47 | 0.876 | 0.93 |

| Renal disease | 0.1695 | 0.36 | 0.640 | 1.18 |

| Rheumatologic disease | -0.2899 | 0.51 | 0.569 | 0.75 |

| Left ventricular systolic dysfunction | -0.0439 | 0.51 | 0.932 | 0.96 |

| Thromboembolism | 1.5718 | 0.53 | 0.003 | 4.82 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.2084 | 0.38 | 0.587 | 1.23 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.0641 | 0.27 | 0.809 | 1.07 |

| Peripheral artery disease | -0.4257 | 0.65 | 0.513 | 0.65 |

| CHADS2 scoreb (reference: 2 [moderate risk]) | ||||

| 0-1 (low risk) | -0.0593 | 0.27 | 0.827 | 0.94 |

| 3-6 (high risk) | 0.2707 | 0.28 | 0.340 | 1.31 |

| HAS-BLED scorec (reference: 2 [moderate risk]) | ||||

| 0-1 (low risk) | -0.2080 | 0.49 | 0.673 | 0.81 |

| 3-9 (high risk) | 0.3301 | 0.29 | 0.263 | 1.39 |

| Number of prior hospitalizations | -0.1601 | 0.33 | 0.630 | 0.85 |

| Stay include time in the ICU/CCU (reference: no) | 0.5457 | 0.25 | 0.030 | 1.73 |

| Hospital U.S. Census divisions (reference: Pacific) | ||||

| New England | 1.9841 | 0.49 | < 0.001 | 7.27 |

| Middle Atlantic | 0.0420 | 0.45 | 0.926 | 1.04 |

| East North Central | 0.1676 | 0.46 | 0.717 | 1.18 |

| West North Central | -0.0209 | 0.49 | 0.966 | 0.98 |

| South Atlantic | -0.2324 | 0.30 | 0.441 | 0.79 |

| East South Central | -0.3914 | 0.51 | 0.444 | 0.68 |

| West South Central | -0.1847 | 0.44 | 0.673 | 0.83 |

| Mountain | Insufficient datad | |||

| Hospital bed size (reference: 300-499 beds) | ||||

| 1-199 beds | -0.0930 | 0.31 | 0.763 | -0.09 |

| 200-299 beds | 0.1084 | 0.44 | 0.806 | 0.11 |

| 500+ beds | -0.4856 | 0.42 | 0.250 | -0.49 |

| Hospital location (reference: rural) | ||||

| Urban | -0.4439 | 0.45 | 0.325 | 0.64 |

| Unknown | -0.7643 | 0.70 | 0.276 | 0.47 |

| Hospital type (reference: community) | ||||

| Academic | -0.3420 | 0.29 | 0.244 | 0.71 |

aGeneralized linear model with binomial distribution, fitted by generalized estimating equations performed using The Comprehensive R Archive Network geepack package.

bOne point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years, and diabetes mellitus; 2 points for transient ischemic attack or stroke.

cOne point each for current or prior hypertension; impaired kidney function (i.e., kidney disease); impaired liver function (i.e., liver disease); stroke, major bleeding event, or having condition that predisposes (i.e., bleeding diathesis); medication use that predisposes to risk of bleeding; abnormal INR (low detection rates in these data); alcohol abuse (low detection rates in these data); and age > 65 years.

dThe 22 patients from the Mountain Census Division were removed from the sample as none were readmitted; retaining them was mathematically skewing the model betas.

AF = atrial fibrillation; ICU/CCU=intensive care unit/critical care unit; INR = international normalized ratio; LMWH/PS = low molecular weight heparin/pentasaccharide; UFH = unfractionated heparin.

Hospitalizations in the U.S. Census Mountain geographic area (n = 9 dabigatran and 13 warfarin) were excluded in the assessment of readmission likelihood, since none represented readmissions, and their inclusion would impact proper development of the model coefficients. The estimated percentage of readmissions adjusted by covariates was similar in the 2 cohorts: 13.1% and 13.3% in the dabigatran and warfarin cohorts, respectively (odds ratio = 0.987, 95% confidence interval = 0.65-1.49, P = 0.951). Not many variables included in the model are associated with significant influence on the likelihood of a hospital readmission (Table 4). Those that do should be considered within the limits of the sample representation (i.e., only 3% [n = 17] of the matched dabigatran and 8% [n = 99] of the matched warfarin patients had a history of thromboembolism).

Table 5 shows the adjusted average inpatient care cost for the index encounter and all readmissions within 30 days following discharge from the index encounter among the subset of hospitalizations with at least 1 readmission. Among this subset of 31 dabigatran and 72 warfarin hospitalizations, the index hospitalization costs and the readmission costs were not statistically different between the dabigatran and warfarin cohorts (index costs: $9,803 vs. $9,755, respectively, with difference of $48, P = 0.944; readmission costs: $10,403 vs. $11,911, respectively, with difference of $1,507, P = 0.375).

TABLE 5.

Adjusted Average Inpatient Care Costs for Index Encounter and All Readmissions During 30 Days Postdischarge Between Dabigatran and Warfarin Treatment Groups

| Measure | Dabigatran Etexilate Adjusteda Average Value | Warfarin Adjusteda Average Value | Difference (Dabigatran Minus Warfarin) | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index encounter inpatient care costs, $ (n) | 9,803 (244) | 9,755 (488) | 48 | 0.944 |

| All inpatient care costs from readmissions within 30 days of discharge of index encounter, $ (n) | 10,403 (31) | 11,911 (72) | -1,507 | 0.375 |

aAdjusted values were estimated using a generalized linear model with gamma distribution, fitted by generalized estimating equations performed using The Comprehensive R Archive Network geepack package.

bStatistical testing at alpha = 0.05 level. Welch 2 sample t-test for differences in means, assuming unequal variances.

Discussion

This study was based on a national multipayer dataset for analyses of real-world use of dabigatran and warfarin in a geographically dispersed sample of hospitals. Patients with newly diagnosed AF account for a significant portion of hospitalizations due to dysrhythmias in the United States.2,3 The study encounters included only newly diagnosed/newly treated NVAF patients to reduce the possibility of biased estimates from the limited control for length of treatment time or switching of treatments. The demographics and clinical history of the sample were similar to those among the U.S. general population with newly diagnosed AF and with emergency department patients presenting with recent onset AF in Italy.32,33 Interestingly, both of these studies reported undertreatment with anticoagulation therapy in up to 25% of patients at high risk of stroke, highlighting that appropriate anticoagulation management remains a worldwide problem.

The total inpatient care costs finding in the current study are comparable with other studies. According to Coyne et al. (2006), the typical AF hospitalization cost in 2001 using 2005 U.S. dollars was $8,371 (total of $2.93 billion for 350,000 hospitalizations with AF as the primary diagnosis).3 Our study’s higher cost estimates ($14,794 and $16,826) are based on costs of actual hospital resources (vs. payments), include primary and secondary AF diagnosed encounters of only newly diagnosed patients, and were based on 2011-2012 data and U.S. dollars. Results using this study’s data and replication of methods with the exception of propensity score matching confirmed the results of lower costs (by $4,240) among the dabigatran cohort. While cost-effectiveness does not always translate to a lower cost solution, several studies have identified dabigatran to be a cost-effective alternative. For instance, a cost-effectiveness analysis model showed dabigatran 150 mg twice daily to be a cost-effective alternative to INR-adjusted warfarin for patients aged ≥ 65 years.34 A decision analysis model of dabigatran cost effectiveness versus warfarin stratified results by INR control, stroke risk, and bleeding risk and showed that dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was cost-effective for patients with high stroke and hemorrhage risk.35 Freeman et al. (2010) used a Markovian analytical model to assess costs and reported that dabigatran could be a cost-effective alternative to warfarin in patients aged ≥ 65 years at increased risk for stroke.36 These studies in tandem with our results suggest that dabigatran use is cost-effective and a lower cost option for OAC therapy. Additional studies should be conducted to validate this.

Patients receiving dabigatran may not need bridging agents because of a rapid onset of action and predictable pharmacokinetics; however, the findings indicated nearly three quarters of the unmatched and matched dabigatran etexilate cohort (71% and 74%, respectively) were observed receiving bridging agents during hospitalization. This contributed significantly to the cost in the dabigatran cohort. Other than intended warfarin use, predictors of bridging are not well defined for newly diagnosed/newly treated NVAF patients, and use of bridging agents remains a challenge in AF patients.37 One study found that among diagnosed AF patients undergoing temporary interruption of anticoagulation therapy for invasive procedures, bridging agents were used inappropriately in more than 50% of patients at low thromboembolic risk.38 Patients hospitalized with a primary or secondary discharge diagnosis of NVAF have also been shown to have increased LOS when bridging agents are used.39 Therefore, including bridging agents as a covariate in the present analysis was done as a reflection of observed, real-world clinical practice.

We found that dabigatran relative to warfarin was associated with a shorter LOS for inpatient encounters, which is consistent with the study by Tan et al. (2007) that demonstrated longer LOS for AF patients newly started versus not initiated on warfarin while in the hospital.40 Thirty percent of patients had delayed discharges attributed to initiation of warfarin, for a combined 17% of delayed days. Additional hospitalization time required for patients treated with warfarin may be driven by the need to titrate to the correct dose determined by monitoring the patient’s INR.

For the subset of hospitalizations analyzed for readmission within 30 days, rates of readmission and total readmission costs were similar between the cohorts. In current literature, readmission rates are reported to be lower when discharged patients have follow-up visits with physicians within 30 days of discharge.41 Our study did not account for follow-up care to a practitioner or, for warfarin, to an anticoagulation clinic for dose monitoring. If either cohort had a greater compliance with therapy after discharge or higher proportion that followed up with a clinic or physician, this could be insightful in interpreting our results that readmission rates and costs were similar for encounters involving dabigatran and warfarin.

Limitations

Despite the strength of the methodological approaches and analyses in this large retrospective, observational study, there are certain limitations. Charges modified by cost-to-charge ratios estimated the cost of hospital resources used but may over- or underrepresent the actual amount reimbursed by payers. Since clinical characteristics were determined using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes on nondiagnostic claims, errors from coding inaccuracies could not be ruled out. Abnormal INR and alcohol abuse, 2 elements in HAS-BLED, may be underdetected using only diagnostic codes. The primary diagnosis was assumed to be consistent with the principal diagnosis reported. The analysis could not identify nor correct for data entry errors at the site of care. Finally, given the data used for this study, we could not assess compliance with anticoagulation therapy among each group or follow up with INR monitoring among the warfarin cohort. However, despite these limitations, the study presented hospitalized cohorts that were well matched with respect to demographics and medical history and identified how attributes among similar populations given different therapies might impact hospital utilization.

Conclusions

The length of stay was longer and total inpatient care costs were higher for hospitalizations of newly diagnosed NVAF patients initiated on warfarin as compared with those initiated on dabigatran. The estimated readmission rates and associated inpatient care costs of 30-day readmissions among dabigatran and warfarin groups were similar.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Patrice C. Ferriola, PhD (KZE PharmAssociates), for assistance with writing this manuscript, and Max Manzi for his assistance with code development and data extraction; all prior acknowledged work was funded by IMS Health. We also acknowledge David R. Walker, PhD, an employee at Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals during the conduct of the study analyses, for his assistance in study design and interpretation.

APPENDIX A. List of Oral Anticoagulants and Corresponding Drug Classification

| Study Drug | First 10 Digits of GPIa | Drug Note Termsb |

|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran etexilate | 83-33-70-30-20 | dabigatran, dabigatran etexilate, pradaxa, dabigat, dabigatran etexilate mesylate |

| Warfarin | 83-20-00-30-20 | warfarin sodium, warfarin, coumadin, jantoven |

aGPI is a 14-digit drug classification system maintained by Medi-Span. The first 10 digits represent drug group-subclass-name-name extension. The remaining 4 digits represent dosage form-strength.

bWhile GPI-10s were used to search the pharmacy claims database, the data source—hospital Charge Detail Masters—used for hospitalizations contains drug notes and not specific drug codes. Additional drug note terms were used (e.g., common misspellings).

GPI = Generic Product Identifier.

APPENDIX B. ICD-9-CM Codes Used to Identify Conditions Reported in Results Section

| Medical Condition | ICD-9-CM Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Thromboembolism | 444* | arterial embolism and thrombosis |

| 445* | atheroembolism | |

| 415.1* | pulmonary embolism and infarction | |

| 449* | septic arterial embolism | |

| 451* | phlebitis and thrombophlebitis | |

| 452* | portal vein thrombosis | |

| 453* | other venous embolism and thrombosis | |

| Coronary artery disease | 411.8* | other acute and subacute forms of ischemic heart disease |

| 413* | angina pectoris | |

| 414.0* | coronary atherosclerosis | |

| Hypertension | 401* | essential hypertension |

| 402* | hypertensive heart disease | |

| 403* | hypertensive chronic kidney disease | |

| 404* | hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease | |

| 405* | secondary hypertension | |

| Congestive heart failurea | 398.91 | rheumatic heart failure (congestive) |

| 402.01 | malignant hypertensive heart disease with heart failure | |

| 402.11 | benign hypertensive heart disease with heart failure | |

| 402.91 | unspecified hypertensive heart disease with heart failure | |

| 404.01 | hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, malignant, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage I through stage IV, or unspecified | |

| 404.03 | hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, malignant, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage V or end stage renal disease | |

| 404.11 | hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, benign, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage I through stage IV, or unspecified | |

| 404.13 | hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, benign, with heart failure and chronic kidney disease stage V or end stage renal disease | |

| 404.91 | hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, unspecified, with heart failure and with chronic kidney disease stage I through stage IV, or unspecified | |

| 404.93 | hypertensive heart and chronic kidney disease, unspecified, with heart failure and chronic kidney disease stage V or end stage renal disease | |

| 425.4 | other primary cardiomyopathies | |

| 425.5 | alcoholic cardiomyopathy | |

| 425.7 | nutritional and metabolic cardiomyopathy | |

| 425.8 | cardiomyopathy in other diseases classified elsewhere | |

| 425.9 | secondary cardiomyopathy, unspecified | |

| 428* | heart failure | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 490* | bronchitis, not specified as acute or chronic |

| 491* | chronic bronchitis | |

| 492* | emphysema | |

| 493* | asthma | |

| 494* | bronchiectasis | |

| 495* | extrinsic allergic alveolitis | |

| 496* | chronic airway obstruction, not elsewhere classified | |

| 500* | coal workers’ pneumoconiosis | |

| 501* | asbestosis | |

| 502* | pneumoconiosis due to other silica or silicates | |

| 503* | pneumoconiosis due to other inorganic dust | |

| 504* | pneumonopathy due to inhalation of other dust | |

| 505* | pneumoconiosis, unspecified | |

| 506.4 | chronic respiratory conditions due to fumes and vapors | |

| Diabetes mellitusb | 249* | secondary diabetes mellitus |

| 250* | diabetes mellitus | |

| 362.0* | diabetic retinopathy | |

| 366.41 | diabetic cataract | |

| V12.21 | personal history of gestational diabetes | |

| V58.67 | long-term (current) use of insulin | |

| V65.46 | encounter for insulin pump training | |

| Stroke/TIA | 430* | subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| 431* | intracerebral hemorrhage | |

| 432* | other and unspecified intracranial hemorrhage | |

| 433* | occlusion and stenosis of precerebral arteries | |

| 434* | occlusion of cerebral arteries | |

| 435* | transient cerebral ischemia | |

| 436* | acute but ill-defined cerebrovascular disease | |

| 437.1 | other generalized ischemic cerebrovascular disease | |

| 438* | late effects of cerebrovascular disease | |

| 997.02 | iatrogenic cerebrovascular infarction or hemorrhage | |

| V12.54 | personal history of TIA and cerebral infarction without residual deficits |

aThis congestive heart failure definition is used in the Charlson Comorbidity Index. The stroke risk definition does not include the codes 402.01-404.93 but does include additional codes 425.0-425.3, 674.5, 674.53, and 674.54.

bThis diabetes mellitus definition is for stroke risk. The Charlson Comorbidity Index definition24 is limited to 249* and 250*.

ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

APPENDIX C. List of Bridging Agents and Corresponding Drug Note Terms

| Bridging Agent Group | Drugs | Drug Note Termsa |

|---|---|---|

| Low molecular weight heparin/pentasaccharide | fondaparinux | fondiparinux, fondaparinux sodium, Arixtra |

| enoxaparin | enoxaparin, enox, Lovenox | |

| dalteparin | dalteparin, daltep, Fragmin | |

| nondrug specific reference to low molecular weight heparin/pentasaccharide | ||

| Unfractionated heparin | heparin | Heparin, Hep, Heparin Lock, Beef Heparin, Heparin (porcine), Heparin sodium |

aThe data source—hospital Charge Detail Masters—used to assess hospitalizations contains drug notes and not specific NDC numbers or HCPCS codes. Additional drug note terms were used (e.g., common misspellings).

HCPCS = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; NDC = National Drug Code.

References

- 1.Wattigney WA, Mensah GA, Croft JB.. Increasing trends in hospitalization for atrial fibrillation in the United States, 1985 through 1999: implications for primary prevention. Circulation. 2003;108(6):711-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFrances CJ, Cullen KA, Kozak LJ.. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2005 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat 13. 2007;13(165):1-209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne KS, Paramore C, Grandy S, Mercader M, Reynolds M, Zimetbaum P.. Assessing the direct costs of treating nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the United States. Value Health. 2006;9(5):348-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonald AJ, Pelletier AJ, Ellinor PT, Camargo CA Jr.. Increasing US emergency department visit rates and subsequent hospital admissions for atrial fibrillation from 1993 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(1):58-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marzona I, O’Donnell M, Teo K, et al. Increased risk of cognitive and functional decline in patients with atrial fibrillation: results of the ONTARGET and TRANSCEND studies. CMAJ. 2012;184(6):E329-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singer DE, Chang Y, Fang MC, et al. The net clinical benefit of warfarin anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(5):297-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.COUMADIN (warfarin sodium) full prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb. Revised October 2011. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/009218s107lbl.pdf. Accessed September 14, 2015.

- 9.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, O’Donnell M, Pogue J, Yusuf S.. Challenges of establishing new antithrombotic therapies in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2007;116(4):449-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Spall HG, Wallentin L, Yusuf S, et al. Variation in warfarin dose adjustment practice is responsible for differences in the quality of anticoagulation control between centers and countries: an analysis of patients receiving warfarin in the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy (RE-LY) trial. Circulation. 2012;126(19):2309-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bendel SD, Bona R, Baker WL.. Dabigatran: an oral direct thrombin inhibitor for use in atrial fibrillation. Adv Ther. 2011;28(6):460-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(12):1139-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Reilly PA, Wallentin L.. Newly identified events in the RE-LY trial. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(19):1875-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diener HC, Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Dabigatran compared with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and previous transient ischaemic attack or stroke: a subgroup analysis of the RE-LY trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(12):1157-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ezekowitz MD, Wallentin L, Connolly SJ, et al. Dabigatran and warfarin in vitamin K antagonist-naive and -experienced cohorts with atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2010;122(22):2246-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH, Skjøth F, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran etexilate and warfarin in “real world” patients with atrial fibrillation: a prospective nationwide cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(22):2264-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black JT. Learning about 30-day readmissions from patients with repeated hospitalizations. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(6):e200-01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. 2013. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed September 14, 2015.

- 19.D’Agostino RJ Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17(19):2265-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin PC. Statistical criteria for selecting the optimal number of untreated subjects matched to each treated subject when using many-to-one matching on the propensity score. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(9):1092-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat. 2011;10(2):150-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA.. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karthikeyan G, Eikelboom JW.. The CHADS2 score for stroke risk stratification in atrial fibrillation—friend or foe? Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(1):45-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henriksson KM, Farahmand B, Johansson S, Asberg S, Terént A, Edvardsson N.. Survival after stroke—the impact of CHADS2 score and atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol. 2010;141(1):18-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Apostolakis S, Lane DA, Guo Y, et al. Performance of the HEMORR2HAGES, ATRIA, and HAS-BLED bleeding risk-prediction scores in non-warfarin anticoagulated atrial fibrillation patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(9):861-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roldan V, Marin F, Manzano-Fernandez S, et al. The HAS-BLED Score has better prediction accuracy for major bleeding than CHADS2 or CHA2DS2-VASc scores in anticoagulated patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(23):2199-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omran H, Bauersachs R, Rübenacker S, et al. The HAS-BLED score predicts bleeding during bridging of chronic oral anticoagulation: results from the National Multicentre BNK Online bRiDging REgistRy (BORDER). Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(1):65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho D, Imai K, G K, Stuart E.. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal. 2007;15(3):199-236. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halenkoh U, Hojsgaard S, Yan J.. The R Package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J Stat Softw. 2006;15(2):1-11. Available at: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v15/i02/paper. Accessed September 14, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.IMS Health. Hospital Market Profiling Solution. 1Q 2013 Release. 2013.

- 32.Glazer NL, Dublin S, Smith NL, et al. Newly detected atrial fibrillation and compliance with antithrombotic guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):246-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buccelletti F, Di Somma S, Iacomini P, et al. Assessment of baseline characteristics and risk factors among emergency department patients presenting with recent onset atrial fibrillation: a retrospective cohort study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17(Suppl 1):22-27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adcock AK, Lee-Iannotti JK, Aguilar MI, et al. Is dabigatran cost effective compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation? A critically appraised topic. Neurologist. 2012;18(2):102-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shah SV, Gage BF.. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran for stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2011;123(22):2562-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman JV, Zhu RP, Owens DK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2010;154(1):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo Y, Lip GY, Apostolakis S.. Bridging therapy: a challenging area in the management of patients with atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013;13(4):259-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Omran H, Bauersachs R, Rubenacker S, Goss F, Hammerstingl C.. The HAS-BLED score predicts bleedings during bridging of chronic oral anticoagulation. Results from the national multicentre BNK Online bRiDging REgistRy (BORDER). Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(1):65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smoyer-Tomic K, Siu K, Walker DR, et al. Anticoagulant use, the prevalence of bridging, and relation to length of stay among hospitalized patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2012;12(6):403-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan ES, Bonnett TJ, Abdelhafiz AH.. Delayed discharges due to initiation of warfarin in atrial fibrillation: a prospective audit. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(3):232-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]