Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Endometriosis affects over 10 million women in the United States. Depot leuprolide acetate (LA), a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, has been used extensively for the treatment of women with endometriosis but is associated with hypoestrogenic symptoms and bone mineral density loss. The concomitant use of add-back therapies, specifically norethindrone acetate (NETA), can alleviate these adverse effects.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare adherence to and persistence with LA treatment and time to endometriosis-related surgery among women treated with LA plus NETA and women treated with LA plus other add-back therapies or LA only.

METHODS:

This retrospective analysis was conducted using Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. Women with a diagnosis of endometriosis (ICD-9-CM code 617.xx) who initiated LA (index date) in 2005-2011 were selected for inclusion. Additional requirements were 12 months of continuous enrollment pre- and post-index and no evidence of endometriosis-related surgeries pre-index or up to 30 days post-index; no pre-index use of estrogen or noncontraceptive hormones; and no diagnoses of uterine fibroids, malignant neoplasms, infertility, or pregnancy. Patients were characterized as using NETA; other add-back therapies (estrogens, progestins, or estrogen-progestin combinations); or no add-back therapy. Adherence to and persistence with LA were measured over the 6 months following the index date using outpatient medical and pharmacy claims. Patients were considered adherent if their proportion of days covered was greater than or equal to 0.80. Persistence was operationalized as time to discontinuation, defined as a continuous gap of > 60 days without LA on hand. Time to endometriosis-related surgery (laparotomy, laparoscopy, excision/ablation/fulguration, oophorectomy, and hysterectomy) was measured over the 12 months following the index date. Surgeries were identified from inpatient and outpatient medical claims using procedure codes. Outcomes were compared among cohorts using multivariable logistic and Cox proportional hazards regression models controlling for demographics and baseline clinical characteristics.

RESULTS:

The final sample included 3,114 women, with a mean age of 36.9 years. The majority of women used LA only with no add-back therapy (n = 1,963, 63.0%), while 15.1% (n = 470) used NETA, and 21.9% (N = 681) used other add-back therapies. During the 6-month follow-up, more patients in the LA plus NETA cohort were adherent to LA therapy compared with LA only (47.2% vs. 31.5%, P < 0.001), and fewer patients discontinued (37.9% vs. 59.6%, P < 0.001). Additionally, fewer patients underwent endometriosis-related surgery in the 12 months after LA initiation in the LA plus NETA cohort (12.6% vs. 16.9%, P = 0.021). In multivariable models, women who initiated LA plus NETA or LA plus other add-back therapies had a higher likelihood of being adherent to LA than LA only patients (OR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.55-2.36 and OR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.63-2.34) and lower likelihood of LA discontinuation (HR = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.46-0.63 and HR = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.52-0.68). NETA patients had a lower surgery rate in the 12-month post-index period compared with other add-back patients (HR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.50-0.93) or LA only patients (HR = 0.69, 95% CI = 0.52-0.92).

CONCLUSIONS:

For women with endometriosis, treatment with LA and concomitant add-back therapies was associated with better adherence to and persistence with LA over the 6 months following initiation, compared with treatment with LA only. The increased adherence and persistence to LA may translate into decreased need for surgical intervention, although fewer endometriosis-related surgeries were only observed in the 12 months following LA initiation for patients using concomitant NETA add-back therapy. These results support an increased and earlier use of NETA add-back therapy among women who initiate LA.

What is already known about this subject

Depot leuprolide acetate (LA), a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, has been used extensively for the treatment of women with endometriosis but is associated with menopausal symptoms (hot flashes, vaginal atrophy, and insomnia) and bone mineral density loss.

The tolerability of LA can be increased with concomitant use of add-back therapies, including norethindrone acetate (NETA).

What this study adds

This study evaluated adherence to and persistence with LA over the 6 months following initiation among women who initiated LA and used NETA; women who initiated LA and used other add-back therapies; or women who initiated LA only in a large commercial claims database.

Presence and time to endometriosis-related surgery in the 12 months following LA initiation was also compared among the 3 cohorts.

Women who initiated add-back therapy were more adherent and persistent to LA therapy, and those who used NETA had lower surgery rates.

Endometriosis, characterized by the presence of extrauterine endometrial-like tissue, is a complex gynecological disease that affects over 10 million women in the United States.1-3 Endometriosis affects at least 6%-10% of reproductive-aged women and is present in approximately 38% of women with infertility and approximately 87% of women with chronic pelvic pain.4 Endometriosis can be managed surgically and/or pharmacologically.5 Surgical interventions are characterized by high recurrence rates, morbidity, and complication risks, making this approach a formidable challenge.6 Endometriosis recurrence rates of up to 50% have been reported in the 5 years following laparoscopic surgery,7,8 and many patients undergo multiple surgeries.9,10 Current mainstays of noninvasive pharmacologic therapy are oral contraceptives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), progestogens, androgens, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa).11

GnRHa, such as leuprolide acetate (LA), have been used extensively for the treatment of endometriosis, and the micro-sphere depot formulation of LA administered once a month or once every 3 months provides a more tolerable option than earlier formulations.12 While 3 to 6 months of treatment with GnRHa has been proven efficacious in improving endometriosis-related symptoms, its long-term use is restricted because of several side effects that include hypoestrogenic symptoms, such as hot flashes, headache, and vaginitis, and associated bone mineral density (BMD) loss.7,13 These side effects may be associated with decreased persistence with therapy.12 Concomitant use of add-back therapy along with GnRHa has been found to improve compliance.14 Multiple add-back regimens including estrogen, progestins, and norethindrone acetate (NETA) have been demonstrated to prevent BMD loss, without altering the clinical effectiveness of GnRHa.15-17

In comparison to GnRHa therapy alone, the beneficial impact of adding add-back therapy to GnRHa therapy in reducing the occurrence of osteoporosis and symptoms of postmenopausal syndrome was confirmed in a recently published meta-analysis.18 NETA, a progestin, is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as add-back therapy to be co-administered with LA for up to 12 months.19 In clinical trials that assessed the safety and efficacy of LA along with NETA alone or in combination with low-dose conjugated estrogens, the combination of LA plus add-back therapies provided extended pain relief and BMD preservation.15-17 Similar clinical results regarding reduction in LA-associated BMD loss were reported when LA was given in combination with other add-back agents such as sodium etidronate and low-dose norethindrone and etidronate alone.20,21

Despite higher GnRHa treatment compliance and persistence and a reduced adverse event profile associated with add-back therapy, fewer than 1 in 3 patients treated with GnRHa are estimated to use concomitant add-back therapy.12,22 A previously published analysis using claims data from 2002 to 2004 found that use of add-back therapy was associated with better persistence and compliance to LA.12 We undertook this retrospective study to extend this area of research by assessing adherence to and persistence with LA treatment among women treated with LA plus NETA; women treated with LA only; and women treated with LA in combination with other hormonal add-back therapies using data reflecting real-world use in more recent years, more clearly defined add-back cohorts, and measurement of adherence and persistence to LA over the initial 6-month period of therapy where use of add-back therapy is not currently mandated per label.19 An additional objective was to compare time to endometriosis-related surgery among these cohorts of women to determine the potential effect of add-back therapy on surgery rates.

Methods

Data Source

We used data from the Truven Health MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (Commercial) Database from 2004 to 2012. The database contains the pooled health care utilization records of approximately 39.5 million privately insured individuals in the United States.23 All study data were de-identified and complied with all aspects of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and therefore were exempted from institutional review board approval.

Patient Selection

Adult women (aged 18-49 years) with at least 1 claim (outpatient pharmacy or medical) for LA between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2011, were identified using National Drug Code (NDC) numbers or the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code J1950 for injection, leuprolide acetate (for depot suspension), per 3.75 mg (a separate HCPCS code for the 11.25 mg dose administered every 3 months does not exist). The index date was the first use of LA. Women were required to have at least 1 nondiagnostic medical claim with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis of endometriosis (617.x) in any position in the 12 months pre-index or up to 60 days post-index. Additionally, patients had to be continuously enrolled with medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 months pre-index (pre-index period) and post-index (follow-up period). Patients were excluded from the study sample if their claims records had codes indicating the following (see Appendix A, available in online article):

LA claims in the pre-index period.

Estrogen or noncontraceptive estrogen/progestin combinations claims in the first 11 months of the pre-index period.

Eligard, Viadur, nondepot LA formulations (e.g., subcutaneous or powder compounding forms), depot LA formulations with a strength of > 11.25 mg or strength of 7.5 mg, or medical claim for 1 mg or 7.5 mg of LA during the study period because these are not indicated for endometriosis treatment.

Pregnancy-assisting medications during the study period.

A diagnosis of uterine fibroids, malignant neoplasm of female genitourinary organs, and/or infertility in the pre-index period.

A claim indicative of pregnancy during the study period.

A claim for endometriosis-related surgery (laparoscopy, laparotomy, excision/ablation/fulguration, hysterectomy, or oophorectomy) during the pre-index period or within 30 days post-index.

Exposure Measures

Patients were grouped into 3 cohorts: (1) LA with NETA add-back therapy, (2) LA with other add-back therapies, and (3) LA only. These patients were identified using HCPCS on outpatient medical claims and NDC numbers on outpatient pharmacy claims around the index date. Other add-back therapies were defined as estrogens; progestins, including norethindrone; or estrogen/progestin combinations, except hormone-releasing intrauterine devices or implants and depot medroxyprogesterone (see Appendix A for HCPCS codes and Appendix B for a list of medications, available in online article). Patient medical and pharmacy claims were evaluated for the presence of at least two 30-day claims for add-back therapy occurring 30 days before the index date through 45 days after the last use of LA or at least one 90-day claim occurring during that time period. Patients with NETA claims meeting this definition and no claims for other add-back therapies were included in the LA plus NETA cohort. Patients with other add-back claims meeting this definition were included in the LA plus other add-back cohort. Patients who met the definition for NETA add-back therapy but who had claims for other add-back therapies were included in the LA plus other add-back cohort. All other patients were included in the LA only cohort.

Outcome Measures

The 3 study outcomes measured were adherence to index LA therapy, persistence with index LA therapy, and surgery incidence following LA initiation. LA adherence and persistence were calculated using outpatient medical and pharmacy claims. For outpatient medical claims for LA, an estimated duration of prescription supply was adopted from a previous study as follows: 30 days for HCPCS J1950 if the paid amount on the claim was less than $1,000 and 90 days if the paid amount was $1,000 or more because a separate HCPCS code for the 11.25 mg dose administered every 3 months does not exist.12 Adherence was measured using proportion of days covered (PDC), which is defined as the ratio of the total days during follow-up with LA “on hand” to the number of days in the evaluation period.24 Patients with PDC ≥ 0.80 were considered adherent to LA.24,25 Persistence was measured using the LA discontinuation rate. Discontinuation was defined as a gap of at least 60 days after the runout of the previous LA claim based on service dates and days supply/estimated duration of prescription supply. Time to discontinuation was also measured. The third study outcome was endometriosis-related surgery, defined as at least 1 medical claim with an ICD-9-CM procedure or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code for a laparoscopy, laparotomy, other excision/ablation/fulguration, oophorectomy, or hysterectomy during the follow-up period (Appendix A) with an endometriosis diagnosis code on the same day. The presence of and time to first endometriosis-related surgery were described. Adherence and persistence were evaluated during the first 6 months following LA initiation because this is the recommended length of treatment.26 Treatment beyond 6 months necessitates the addition of add-back therapy, according to the FDA.26 Endometriosis-related surgery was measured over the full follow-up period (12 months). The follow-up period is relevant because another previously published analysis measured other LA treatment outcomes, including pelvic pain and BMD, over a 12-month period.15

Covariates

To account for the multidimensional nature of factors that could affect treatment adherence/persistence, several covariates were captured including demographic and clinical characteristics.27 Baseline demographic characteristics, including age, U.S Census Bureau geographic region, type of residence (urban/rural) and health insurance plan type, were assessed on the index date. Baseline clinical characteristics, including the Deyo Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),28 and comorbid conditions based on the presence of ICD-9-CM diagnosis and CPT procedure codes, and medication use based on NDC numbers and HCPCS codes were assessed during the 12-month pre-index period (Appendix A). Because of the nature of information recorded in claims databases, over-the-counter medication use could not be captured.

Statistical Analysis

All study variables for each study cohort, including demographic and clinical characteristics, medication use, and outcomes, were analyzed descriptively. Categorical variables were compared between cohorts using chi-square tests, whereas continuous variables were compared using t-tests. Multivariable analyses were conducted to compare adherence to and persistence with LA and surgery following LA initiation among the 3 cohorts. The odds of having a PDC ≥ 0.80 at 6 months post-index were modeled using logistic regression with the add-back therapy cohort (NETA, other, or none) as the independent variable. Cox proportional hazards models were employed to estimate time to LA discontinuation over 6 months post-index and time to endometriosis-related surgery over 12 months post-index with the add-back therapy cohort (NETA, other, or none) as the independent variable. Models controlled for age, insurance plan type, region, urbanicity, CCI, pre-index period anxiety diagnosis, pre-index period depression diagnosis, pre-index period opioid prescription, NSAID prescription, and antidepressant prescription. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

A final sample of 3,114 women with endometriosis who met the inclusion criteria were identified between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2011. Of these, 470 (15.1%) received LA plus NETA add-back therapy; 681 (21.9%) received LA plus other add-back therapy; and 1,963 (63.0%) received LA only therapy. There were 202 patients who met the NETA definition but had at least 1 claim for other add-back therapy in the 30 days before the index date or in the 45 days after the last LA claim so were included in the other add-back cohort. Complete patient attrition is described in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Patient Sample Selection Flowchart

Baseline Demographics, Clinical Characteristics, and Medication Use

Demographic and pre-index period clinical characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The mean age across all cohorts ranged between 35.2 and 37.5 years at index. The majority of patients in the study population resided in urban areas (80.1%-81.7%) and was mostly covered by a preferred provider organization (46.2%-51.5%) or health maintenance organization (21.7%-23.8%) plan. Significant differences were observed in the distribution of patients across geographic regions and in the type of health plans between the cohorts. While the proportion of patients in the index years increased consistently from 2005 to 2011 (6.6%-23.2%) in the LA plus NETA add-back cohort, those in the other cohorts had no defined pattern (P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Women with Endometriosis Who Initiated LA

| LA Plus Add-Back: NETA | LA Plus Add-Back: Other Therapies | LA Only | P Value for LA Plus NETA vs. LA Plus Other | P Value for LA Plus NETA vs. LA Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 470 | n = 681 | n = 1,963 | ||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |||

| Mean [SD] age | 36.8 | [7.2] | 35.2 | [7.7] | 37.5 | [7.2] | < 0.001 | 0.047 |

| Population density | ||||||||

| Urban | 81.7 | 384 | 80.5 | 548 | 80.1 | 1,572 | 0.338 | 0.004 |

| Rural | 15.5 | 73 | 17.8 | 121 | 18.9 | 371 | ||

| Unknown | 2.8 | 13 | 1.8 | 12 | 1.0 | 20 | ||

| Geographic region | ||||||||

| Northeast | 18.1 | 85 | 12.6 | 86 | 15.5 | 304 | 0.005 | 0.007 |

| North Central | 23.0 | 108 | 29.8 | 203 | 25.7 | 504 | ||

| South | 42.3 | 199 | 40.4 | 275 | 43.9 | 862 | ||

| West | 13.2 | 62 | 15.4 | 105 | 13.7 | 269 | ||

| Unknown | 3.4 | 16 | 1.8 | 12 | 1.2 | 24 | ||

| Health plan type | ||||||||

| Comprehensive | 3.0 | 14 | 4.0 | 27 | 4.6 | 90 | 0.035 | < 0.001 |

| EPO | 1.5 | 7 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.6 | 11 | ||

| HMO | 23.8 | 112 | 21.7 | 148 | 23.3 | 457 | ||

| POS | 12.3 | 58 | 14.5 | 99 | 14.1 | 277 | ||

| PPO | 46.2 | 217 | 51.5 | 351 | 50.3 | 987 | ||

| POS with capitation | 2.8 | 13 | 1.2 | 8 | 1.8 | 36 | ||

| CDHP | 3.2 | 15 | 2.3 | 16 | 1.2 | 23 | ||

| HDHP | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | ||

| Unknown | 7.0 | 33 | 4.1 | 28 | 3.9 | 77 | ||

| Index Year | ||||||||

| 2005 | 6.6 | 31 | 14.5 | 99 | 11.1 | 218 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| 2006 | 9.8 | 46 | 11.6 | 79 | 14.3 | 281 | ||

| 2007 | 11.9 | 56 | 12.3 | 84 | 15.0 | 294 | ||

| 2008 | 10.2 | 48 | 12.3 | 84 | 12.9 | 253 | ||

| 2009 | 17.9 | 84 | 14.8 | 101 | 14.9 | 292 | ||

| 2010 | 20.4 | 96 | 17.8 | 121 | 16.5 | 324 | ||

| 2011 | 23.2 | 109 | 16.6 | 113 | 15.3 | 301 | ||

CDHP = consumer-driven health plan; EPO = exclusive provider organization; HDHP = high-deductible health plan; HMO = health maintenance organization;

LA = leuprolide acetate; NETA = norethindrone acetate; POS = point-of-service plan; PPO = preferred provider organization; SD = standard deviation.

TABLE 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Women with Endometriosis Who Initiated LA

| LA Plus Add-Back: NETA | LA Plus Add-Back: Other Therapies | LA Only | P Value for LA Plus NETA vs. LA Plus Other | P Value for LA Plus NETA vs. LA Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 470 | n = 681 | n = 1,963 | ||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |||

| Mean [SD] Deyo CCI | 0.2 | [0.6] | 0.2 | [0.6] | 0.3 | [0.7] | 0.932 | 0.472 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||||

| Anxiety | 10.0 | 47 | 8.7 | 59 | 7.4 | 146 | 0.441 | 0.065 |

| Depression | 9.6 | 45 | 9.8 | 67 | 7.8 | 154 | 0.882 | 0.219 |

| Dysmenorrhea | 14.5 | 68 | 14.2 | 97 | 12.5 | 245 | 0.915 | 0.248 |

| Excessive or frequent menstruation | 12.6 | 59 | 11.5 | 78 | 17.3 | 339 | 0.571 | 0.013 |

| Unspecified symptoms of female genital organs | 42.3 | 199 | 40.5 | 276 | 36.7 | 720 | 0.539 | 0.023 |

| Abdominal/pelvic pain | 35.3 | 166 | 32.9 | 224 | 32.0 | 628 | 0.393 | 0.167 |

| Medications | ||||||||

| NSAIDs | 40.0 | 188 | 40.2 | 274 | 36.6 | 718 | 0.936 | 0.168 |

| Opioids | 55.5 | 261 | 54.5 | 371 | 50.4 | 990 | 0.724 | 0.047 |

| Androgens | 0.9 | 4 | 1.3 | 9 | 0.4 | 7 | 0.458 | 0.151 |

| Antidepressants | 33.2 | 156 | 33.2 | 226 | 27.5 | 539 | 0.999 | 0.013 |

| Hormonal contraceptives | 27.0 | 127 | 64.2 | 437 | 22.8 | 448 | < 0.001 | 0.054 |

| Hormone-releasing IUD or implant | 0.4 | 2 | 0.7 | 5 | 0.8 | 16 | 0.508 | 0.376 |

| Depot medroxyprogesterone | 4.7 | 22 | 2.1 | 14 | 4.4 | 87 | 0.012 | 0.815 |

| Other progestinsa | 28.3 | 133 | 12.9 | 88 | 8.4 | 164 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

a Noncontraceptive norethindrone, noncontraceptive medroxyprogesterone, and progesterone.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; IUD = intrauterine device; LA = leuprolide acetate; NETA = norethindrone acetate; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs;

SD = standard deviation.

In all cohorts, the most prevalent comorbid conditions evaluated were unspecified symptoms of female genital organs (36.7%-42.3%), abdominal/pelvic pain (32.0%-35.3%), dysmenorrhea (12.5%-14.5%), and excessive/frequent menstruation (11.5%-17.3%). The proportion of patients with unspecified symptoms of female genital organs and excessive/frequent menstruation differed significantly between the LA plus NETA add-back therapy cohort and the LA only cohort (P < 0.03). Opioids (50.4%-55.5%), NSAIDs (36.6%-40.2%), hormonal contraceptives (22.8%-64.2%), and antidepressants (27.5%-33.2%) were the most commonly used medications in the pre-period. Opioid and antidepressant use were significantly more prevalent in the LA plus NETA add-back cohort compared with the LA only cohort (P < 0.05). The proportion of patients with a claim for hormonal contraceptive was also significantly lower in the LA plus NETA cohort, compared with the LA plus other add-back cohort (P < 0.001), since hormonal contraceptives use in the 30 days before index was considered in the other add-back category.

Unadjusted Results

Unadjusted results are presented descriptively in Table 3 and Figure 2A and 2B. Over the 6-month post-index period during which LA adherence was measured, women treated with LA plus NETA add-back therapy had significantly (P < 0.001) higher mean PDC of LA (mean = 0.70, standard deviation [SD] 0.27, median = 0.78, interquartile range [IQR] = 0.49-0.94) compared with patients in the LA only cohort (mean = 0.56, [SD 30], median = 0.50, IQR = 0.32-0.87). A significantly greater proportion of patients receiving NETA add-back achieved PDC ≥ 0.80 compared with those without add-back therapy (47.2% vs. 31.5%, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference between LA plus NETA add-back therapy and LA plus other add-back therapy in therapy terms of mean PDC (LA plus other: mean = 0.68, [SD 0.28], median = 0.77, IQR = 0.47-0.93) or proportion adherent (LA plus other: 47.9%) The proportion of patients in the LA plus NETA add-back cohort who discontinued LA therapy within 6 months was significantly lower than the LA only cohort (37.9% vs. 59.6%; P < 0.001). Patients with add-back therapy had longer LA persistence than patients with LA only (mean = 139 days [SD 56.0] vs. mean = 111 days [SD 62.3], P < 0.001). Unadjusted time to discontinuation for the 3 cohorts is presented as a Kaplan-Meier curve in Figure 2A; approximately 10% restarted LA after discontinuing within the 6 months following the index date.

TABLE 3.

Adherence and Persistence with LA (6 Months) and Time to Surgery (12 Months) Following LA Initiation Among Women with Endometriosis

| LA Plus Add-Back: NETA | LA Plus Add-Back: Other Therapies | LA Only | P Value for LA Plus NETA vs. LA Plus Other | P Value for LA Plus NETA vs. LA Only | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 470 | n = 681 | n = 1,963 | ||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |||

| Persistence | ||||||||

| Discontinued during 6 months | 37.9 | 178 | 40.2 | 274 | 59.6 | 1,169 | 0.420 | < 0.001 |

| Restarted LAa | 18.5 | 33 | 13.5 | 37 | 7.8 | 91 | 0.148 | < 0.001 |

| Mean [SD] days persistent during 6 months | 139 | [56.0] | 136 | [57.4] | 111 | [62.3] | 0.356 | < 0.001 |

| Adherence | ||||||||

| Mean [SD] PDC during 6 months | 0.70 | [0.27] | 0.68 | [0.28] | 0.56 | [0.30] | 0.398 | < 0.001 |

| PDC ≥ 80 | 47.2 | 222 | 47.9 | 326 | 31.5 | 619 | 0.193 | < 0.001 |

| Endometriosis-related surgery | ||||||||

| Had surgery | 12.6 | 59 | 16.9 | 115 | 16.9 | 332 | 0.044 | 0.021 |

| Laparotomy | 0.9 | 4 | 0.3 | 2 | 1.0 | 19 | 0.197 | 0.814 |

| Laparoscopy | 3.6 | 17 | 5.3 | 36 | 4.0 | 79 | 0.184 | 0.684 |

| Other excision/ablation/fulguration | 4.5 | 21 | 5.4 | 37 | 5.2 | 103 | 0.462 | 0.490 |

| Oophorectomy | 1.7 | 41 | 12.2 | 83 | 12.2 | 239 | 0.062 | 0.035 |

| Mean [SD] days to endometriosis-related surgery, among those who had surgery | 185 | [86.4] | 167 | [94.7] | 139 | [94.9] | 0.217 | 0.001 |

| Mean [SD] days to laparotomy | 151 | [89.2] | 250 | [115.3] | 169 | [111.8] | 0.301 | 0.762 |

| Mean [SD] days to laparoscopy | 161 | [105.4] | 181 | [102.4] | 155 | [92.0] | 0.502 | 0.814 |

| Mean [SD] days to other excision/ablation/fulguration | 165 | [96.5] | 185 | [103.9] | 146 | [96.7] | 0.476 | 0.408 |

| Mean [SD] days to oophorectomy | 195 | [41.0] | 170 | [97.7] | 144 | [79.2] | 0.500 | 0.086 |

| Mean [SD] days to hysterectomy | 189 | [81.2] | 153 | [89.3] | 137 | [94.3] | 0.032 | 0.001 |

a Denominator is the number of patients who discontinued LA.

LA = leuprolide acetate; NETA = norethindrone acetate; PDC = proportion of days covered; SD = standard deviation.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier Curves for Persistence and Surgery

Compared with the LA plus NETA add-back therapy cohort, a significantly higher proportion of patients underwent endometriosis-related surgery in the LA only cohort (12.6% vs. 16.9%, P = 0.021) during the 12-month follow-up period. Hysterectomy was the most common procedure performed (11.7% of entire study population), while laparotomy (0.8% of the entire study population) was rare. Among those who had surgery, patients in the LA plus NETA add-back therapy cohort had significantly longer average time to surgery compared with those in the LA only cohort (mean = 185 days [SD 86.4] vs. mean = 139 days [SD 94.9], P = 0.001). Figure 2B presents unadjusted time to surgery. The proportion of patients who had surgery over the 12-month follow-up period was significantly lower for women who were adherent to LA over the first 6 months compared with those who were not adherent (LA plus NETA add-back: 8.6% vs. 16.1%, P = 0.013; LA plus other add-back: 10.4% vs. 22.8%, P < 0.001; LA only: 9.7% vs. 20.2%, P < 0.001). The same trend was observed for women who were persistent compared with those who were nonpersistent to LA over 6 months (LA plus NETA add-back: 9.6% vs. 17.4%, P = 0.013; LA plus other add-back: 11.3% vs. 25.2%, P < 0.001; LA only: 11.2% vs. 20.8%, P < 0.001).

Adjusted Results

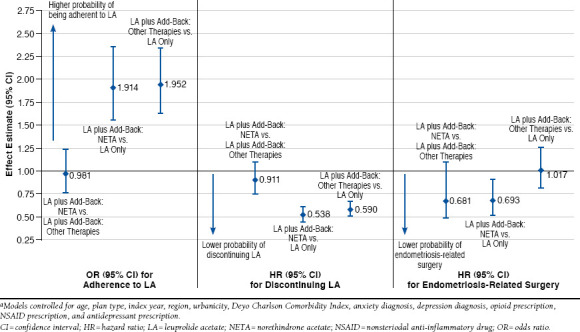

Figure 3 contains the multivariable analysis results. Initiating LA plus NETA add-back therapy was associated with increased odds of PDC ≥ 0.80 compared with initiating LA only (odds ratio [OR] = 1.914, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.554-2.358, P < 0.001) when controlling for baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and concomitant medications. Patients initiating LA plus other add-back therapies also had significantly greater odds of being adherent than LA only patients (OR = 1.952, 95% CI = 1.628-2.340, P < 0.001). Patients in the LA plus NETA add-back cohort had significantly lower hazards of discontinuation compared with those treated with LA only (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.538, 95% CI = 0.459-0.631, P < 0.001), as did patients initiating LA plus other add-back therapies (HR = 0.590, 95% CI = 0.516-0.675, P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in adherence or persistence when comparing the LA plus NETA cohort with the LA plus other add-back cohort. However, LA plus NETA add-back therapy was associated with decreased hazards of surgery compared with those with LA plus other add-back therapies (HR = 0.681, 95% CI = 0.496-0.934, P = 0.017) and those treated with LA only (HR = 0.693, 95% CI = 0.523-0.917, P = 0.010).

FIGURE 3.

Multivariable Adjusted Results for Adherence, Persistence, and Endometriosis-Related Surgery Among Women with Endometriosis Who Initiated LAa

Discussion

In a commercially insured population, women with endometriosis treated with LA plus NETA were more likely to be adherent to and persistent with LA for 6 months, compared with patients treated with LA only, and were less likely to have surgery within 12 months, compared with women treated with LA plus other add-back therapies or LA only. There is also an indication that women who are adherent and persistent to LA have lower rates of surgery. This is currently being explored further in a separate analysis. A recently published meta-analysis confirmed the beneficial effects of adding add-back therapies to GnRHa therapy for endometriosis because add-back therapies reduce the occurrence of osteoporosis and postmenopausal syndrome symptoms compared with GnRHa therapy alone.18 Use of add-back therapies with a GnRHa, such as LA, is also known to enhance persistence and adherence of LA treatment in patients.12,15 Better improvement in the quality of life measures for a longer period of time were also reported in women treated with GnRHa plus add-back therapies, compared with GnRHa or oral contraceptive treatments alone.29,30 Since the NETA cohort and other add-back cohort had similar levels of LA adherence and persistence, the difference in surgery risk between the 2 add-back cohorts may be due to use of estrogens by some women in the other add-back cohort. Estrogen use can negate the effects of LA therapy because estrogen stimulates the growth of endometrial tissue.31,32 It is important to note that the other add-back cohort is heterogeneous with respective to add-back therapy composition. Therefore, results for that cohort should be interpreted cautiously because individual types of add-back therapy (estrogens, progestins, or combinations thereof) may have different associations with adherence, persistence, and surgery.

Among the add-back therapies, the hormonal profile of NETA has been shown to exhibit strong endometrial antiproliferative effects and to reduce BMD losses and vasomotor symptoms, such as hot flashes, commonly encountered by women treated with GnRHa.32 The combination of LA and NETA may alleviate the side effects of LA only, resulting in patients staying on the medication for longer periods of time. Although the reduction in number and size of endometriotic lesions was only shown for LA monotherapy,26,33 one could speculate that LA’s benefit would be likewise present for LA plus add-back therapy, potentially leading to a reduced need for, or a delay in, endometriosis-related surgery. Reducing the need for surgery is expected to be associated with economic savings, given the considerable costs of endometriosis-related surgeries together with rates of complications associated with those procedures.34

This analysis used a large commercial insurance database to describe improved adherence and reduced surgery rates associated with the use of LA and add-back therapy in a database with sufficient sample size and longitudinality to yield robust comparisons. Additionally, the definition of study cohorts produced a clean cohort of patients using LA plus NETA without any other add-back therapies for comparison with LA only patients. The methods employed in this study were influenced by a previous study comparing LA adherence and persistence by Fuldeore et al (2010).12 This previous analysis was conducted with MarketScan data from 2002 to 2004. Similar to our analysis, the index date was initiation of LA. Evidence of claims for add-back therapy (estrogen, progestin, or norethindrone) was measured in the 7 days before the index date through 45 days after. Persistence and compliance (measured as medication possession ratio [MPR]) were evaluated over 12 months and found to be better among women with evidence of add-back therapy.12

Our analysis varied in several ways. First, the data used in this analysis are reflective of current utilization patterns, compared with the data used in the Fuldeore et al. analysis.12 Second, we evaluated adherence and persistence over a 6-month period, which is consistent with LA prescribing information for initial endometriosis management. Patients using LA for periods longer than 6 months should be concurrently using add-back therapy per the drug label. We conducted a sensitivity analysis where we measured these outcomes over the 12 months following LA initiation (data not shown), which yielded results similar to the previous analysis of LA and add-back therapy conducted by Fuldeore et al.12 Over a 12-month period, we found an average PDC of 0.42 for LA plus NETA, 0.40 for LA plus other add-back, and 0.31 for LA only. Fuldeore et al.’s analysis reported an average MPR of 0.43 for LA plus NETA patients, 0.32-0.35 for LA plus other add-back therapy, and 0.32 for LA only.12 Regarding LA persistence, we found that patients treated with LA plus NETA persisted on therapy for an average of 5.3 months over the 12-month period, compared with 5.0 months for patients treated with LA plus other add-back therapy and 3.9 for patients treated with LA only. Fuldeore et al. reported times on therapy of 5.8 months, 4.6-5.8 months, and 4.2 months, respectively.12

Third, women with endometriosis-related surgery were excluded from our analysis because they may experience effects related to the surgical intervention in combination with LA effects during the follow-up period. Women who underwent surgery within 30 days of initiating LA were also excluded because LA may be used as preparation for surgery rather than as a treatment on its own. Fourth, we employed multivariable models for adherence controlling for demographic and clinical characteristics because previous research has shown that LA adherence is affected by age, while the Fuldeore et al. analysis only modeled persistence in a descriptive manner that did not account for baseline differences between patients.12

Limitations

There are limitations to our analysis that merit consideration. First, this study was limited to information contained in an administrative claims database. Over-the-counter medications are not captured, since they do not generate insurance claims. Symptoms of endometriosis and comorbid conditions may not be captured correctly if the diagnoses were not recorded by health care providers for reimbursement. Another limitation of the current study is that health care claims databases are not designed primarily to capture adverse events (AEs).35,36 Thus, certain AEs associated with using LA or undergoing laparoscopy may not be collected if the AE did not result in a diagnosis or procedure on a health care claim. Nonetheless, it must be anticipated that a similar safety profile to that seen in LA’s drug labels applies to the study population. Most frequent AEs observed among endometriosis patients are hot flashes, headache, vaginitis, depression/emotional lability, general pain, nausea/vomiting, weight gain or loss, decreased libido, dizziness, acne, and impact on bone health,26 whereas AEs related to undergoing laparoscopy include vascular, intestinal, urinary tract, and nerve injuries.37-42

Second, we used the dose defined as per the label and paid amount to estimate day supply for assigning days supply for LA medical claims because doses are not available on medical claims. Third, ICD-9-CM codes do not contain information on endometriosis stage, which may influence treatment choices and outcomes. Endometriosis stage may have differed between the 3 cohorts and could have affected physicians’ prescribing patterns.

Fourth, this study design was observational; therefore, causal inference should be drawn cautiously. Physician-prescribing patterns and preferences for pharmacotherapy versus surgical treatments, as well as patient preferences could not be captured. Just as differences in endometriosis stage could have biased the study findings, the inability to adjust for physician and patient preferences may have resulted in uncontrolled confounding. Future research using patient and/or physician surveys should be conducted to assess patient and physician preferences and their relationship with surgery rates.

Finally, the analyses were limited to women with commercial insurance, so the results may not be generalizable to women insured through other mechanisms, such as Medicaid, or the uninsured, all of which warrant further research.

Conclusions

This study shows that for women with endometriosis, treatment with LA and concomitant add-back therapy was associated with better adherence to and persistence with LA over the 6 months following initiation compared with treatment with LA only. For women treated with LA along with NETA, the odds of being adherent to LA were 91% higher compared with those treated with LA only. Women treated with LA plus NETA also had 46% lower probability of discontinuing LA over 6 months. There were no significant differences in adherence and persistence between women treated with NETA versus other add-back therapies. However, NETA add-back use was associated with lower risk of endometriosis-related surgery than other add-back therapies. Women treated with LA plus NETA had a 31% lower probability of surgery compared with women treated with LA only and a 32% lower probability of surgery compared with women treated with other therapies. The increased adherence and persistence to LA may translate into decreased need for surgical intervention. These results support increased and earlier use of NETA add-back therapy among women with endometriosis who initiate LA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Kavya Thelakkat, an employee of Truven Health Analytics, who contributed to the preparation and editing of the manuscript. AbbVie provided funding to Truven Health Analytics for preparation and editing of the manuscript. We would also like to thank H. Peter Bacher, MD, PhD, and Damian Gruca, MD, employees of AbbVie, for providing comments on manuscript drafts.

APPENDIX A. Diagnosis and Procedure Codes Used in Analysis

| Code Type | Code | Description | Grouping |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCPCS | J1056 | Injection, medroxyprogesterone acetate/estradiol cypionate, 5 mg/25 mg | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J0900 | Injection, testosterone enanthate and estradiol valerate, up to 1 cc | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J0970 | Injection, estradiol valerate, up to 40 mg | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J1060 | Injection, testosterone cypionate and estradiol cypionate, up to 1 mL | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J1380 | Injection, estradiol valerate, up to 10 mg | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J1390 | Injection, estradiol valerate, up to 20 mg | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J1410 | Injection, estrogen conjugated, per 25 mg | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J1435 | Injection, estrone, per 1 mg | Other add-back |

| HCPCS | J2675 | Injection, progesterone, per 50 mg | Other add-back |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 54.11 | Exploratory laparotomy | Laparotomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 54.12 | Reopening of recent laparotomy site | Laparotomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 54.19 | Other laparotomy | Laparotomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 54.21 | Laparoscopy; peritoneoscopy | Laparoscopy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.81 | Laparoscopic lysis of adhesions of ovary and fallopian tube | Laparoscopy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.89 | Other lysis of adhesions of ovary and fallopian tube | Laparotomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 70.32 | Excision or destruction of lesion of cul-de-sac | Laparotomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 57.59 | Open excision or destruction of other lesion or tissue of bladder | Laparotomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.29 | Other excision or destruction of lesion of uterus | Laparotomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.23 | Endometrial ablation | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 54.3 | Excision or destruction of lesion or tissue of abdominal wall or umbilicus | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 54.4 | Excision or destruction of peritoneal tissue | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.30 | Endoscopic excision or destruction of lesion of duodenum | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.31 | Other local excision of lesion of duodenum | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.32 | Other destruction of lesion of duodenum | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.33 | Local excision of lesion or tissue of small intestine, except duodenum | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.34 | Other destruction of lesion of small intestine, except duodenum | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.41 | Excision of lesion or tissue of large intestine | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.43 | Endoscopic destruction of other lesion or tissue of large intestine (Note: includes both excision and destruction by endoscopic approach) | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 45.49 | Other destruction of lesion of large intestine (Note: open approach) | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.25 | Other laparoscopic local excision or destruction of ovary | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 66.61 | Excision or destruction of lesion of fallopian tube | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 69.19 | Other excision or destruction of uterus and supporting structures | Other excision/ablation |

| CPT | 44200 | Laparoscopy, surgical; enterolysis (separate procedure) | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 49321 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/bx (single/multiple) | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 49322 | Laparoscopy, surgical, abdomen, peritoneum and omentum; w/cavity/cyst | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 49329 | Unlisted procedure, laparoscopy, abdomen, peritoneum and omentum | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56300 | Deleted 01/00 lap dx (separate procedure) | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56301 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/fulg oviducts | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56302 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/occlud oviducts-device | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56303 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/fulg/exc les ovary | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56304 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/lysis adhesions | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56305 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/bx peritoneall surface 1/mx | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56306 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/aspirat | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56309 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/remov leiomyomata | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 56310 | Deleted 01/00 laparoscopy, surgical; enterolysis (freeing of intestinal adhesion) | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58578 | Unlisted procedure, laparoscopy, uterus | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58660 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/lysis, adhesions (salpingolysis/ovariol | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58661 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/removal, adnexal structures | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58662 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/fulguration/excision, lesions of ovary | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58670 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/fulguration of oviducts w/wo transection | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58671 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/occlusion, oviducts by device | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58672 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/fimbrioplasty | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58673 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/salpinostomy | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 58679 | Unlisted procedure, laparoscopy, oviduct/ovary | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 49320 | Laparoscopy, abdomen, peritoneum and omentum; dx w/ or w/o specimen | Laparoscopy |

| CPT | 49000 | Explor laparotomy w/wo bx (separate procedure) | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 49002 | Reopening of recent laparotomy | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 49010 | Explor retroperitoneal (separate procedure) | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 49200 | Exc intra-abd/retroperitoneal tumor | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 49201 | Exc intra-abd tumors/cysts; exten | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 58740 | Lysis adhesions | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 58805 | Drain ovarian cyst (separate procedure); ABD | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 58925 | Ovarian cystectomy unilat/bilat | Laparotomy |

| CPT | 58563 | Hysteroscopy, surgical; w/endometrial ablation | Other excision/ablation |

| CPT | 56356 | Deleted 01/00 hysteroscopy surg; w/endometr ablation | Other excision/ablation |

| CPT | 58353 | Ablation, endometrial, thermal, w/o hysteroscopic guidance | Other excision/ablation |

| CPT | 58356 | Endometrial cryoablation with ultrasonic guidance, including endometrial curettage, when performed | Other excision/ablation |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.3 | Subtotal abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.31 | Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LSH) | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.39 | Other and unspecified subtotal abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.4 | Total abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.41 | Laparoscopic total abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.49 | Other and unspecified total abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.5 | Vaginal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.51 | Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (LAVH) | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.59 | Other and unspecified vaginal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.6 | Radical abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.61 | Laparoscopic radical abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.69 | Other and unspecified radical abdominal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.7 | Radical vaginal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.71 | Laparoscopic radical vaginal hysterectomy (LVRH) | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.79 | Other and unspecified radical vaginal hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.8 | Pelvic evisceration | Used to exclude patients only |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 68.9 | Other and unspecified hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 51925 | Closure of vesicouterine fistula; with hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 56308 | Deleted 01/00 lap surg; w/vag hyst w/wo tube(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58150 | TAH w/wo remov tube(s) - ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58152 | TAH; w/colpo-urethrocystopexy | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58180 | Supracerv ABD hyst w/wo remov tube | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58200 | TAH w/part vaginect w/lymph node | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58210 | Rad ABD hyst w/tot pelvic lymphaden | Used to exclude patients only |

| CPT | 58240 | Pelvic exenteration-gyn malig w/TAH | Used to exclude patients only |

| CPT | 58260 | Vag hyst | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58262 | Vag hyst; w/remov tube and/or ovary | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58263 | Vag hyst; tube/ovary w/repr enteroc | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58267 | Vag hyst; w/colpo-urethrocystopexy | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58270 | Vag hyst; w/repr enterocele | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58275 | Vag hyst w/tot/part colpectomy | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58280 | Vag hyst w/colpect; w/repr enteroce | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58285 | Vag hyst radical | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58290 | Vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58291 | Vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g; with removal of tube(s) and/or | Hysterectomy |

| ovary(s) | |||

| CPT | 58292 | Vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g; with removal of tube(s) and/or ovary(s), with repair of enterocele | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58293 | Vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g; with colpo-urethrocystopexy (Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz type, pereyra type) with or without endoscopic control | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58294 | Vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g; with repair of enterocele | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58541 | Laparoscopy, surgical, supracervical hysterectomy, for uterus 250 g or less | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58542 | Laparoscopy, surgical, supracervical hysterectomy, for uterus 250 g or less; with removal of tube(s) and/or ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58543 | Laparoscopy, surgical, supracervical hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58544 | Laparoscopy, surgical, supracervical hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g; with removal of tube(s) and/or ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58548 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with radical hysterectomy, with bilateral total pelvic lymphadenectomy and para-aortic lymph node sampling (biopsy), with removal of tube(s) and ovary(s), if performed | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58550 | Laparoscopy, surgical; w/ vaginal hysterectomy w/wo removal ovary | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58552 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus 250 g or less; with removal of tube(s) and/or ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58553 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58554 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with vaginal hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g; with removal of tube(s) and/or ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58570 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with total hysterectomy, for uterus 250 g or less | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58571 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with total hysterectomy, for uterus 250 g or less; with removal of tube(s) and/or ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58572 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with total hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58573 | Laparoscopy, surgical, with total hysterectomy, for uterus greater than 250 g; with removal of tube(s) and/or ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 59135 | Surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy; interstitial, uterine pregnancy requiring total hysterectomy | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 59136 | Surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy; interstitial, uterine pregnancy with partial resection of uterus | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | S2078 | Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (subtotal hysterectomy), with or without removal of tube(s), with or without removal of ovary(s) | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58953 | Bilat salpingo-oophorect w/omentect, total abdom | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58954 | Bilat salping-oophorec w/omentec, tl abdom hyst & lymphadenectomy | Hysterectomy |

| CPT | 58956 | Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with total omentectomy, total abdominal hysterectomy for malignancy | Hysterectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.3 | Unilateral oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.31 | Laparoscopic unilateral oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.39 | Other unilateral oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.4 | Unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.41 | Laparoscopic unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.49 | Other unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.5 | Bilateral oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.51 | Other removal of both ovaries at same operative episode | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.52 | Other removal of remaining ovary | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.53 | Laparoscopic removal of both ovaries at same operative episode | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.54 | Laparoscopic removal of remaining ovary | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.6 | Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.61 | Other removal of both ovaries and tubes at same operative episode | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.62 | Other removal of remaining ovary and tube | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.63 | Laparoscopic removal of both ovaries and tubes at same operative episode | Oophorectomy |

| ICD-9-CM procedure | 65.64 | Laparoscopic removal of remaining ovary and tube | Oophorectomy |

| CPT | 58940 | Oophorectomy part/tot unilat/bilat | Oophorectomy |

| CPT | 58943 | Oophorectomy; ovarian malig w/bx | Oophorectomy |

CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; HCPCS = Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System; ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

APPENDIX B. List of Add-Back Therapy Medications

| NETA Add-Back Therapies | Other Add-Back Therapies |

|---|---|

| Norethindrone acetate | Conjugated estrogens |

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone | |

| acetate | |

| Conjugated estrogens/meprobamate | |

| Desogestrel/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Drospirenone/estradiol | |

| Drospirenone/ethinyl estradiol/levomefolate | |

| calcium | |

| Esterified estrogens | |

| Esterified estrogens/methyltestosterone | |

| Estradiol | |

| Estradiol acetate | |

| Estradiol cypionate | |

| Estradiol cypionate/medroxyprogesterone | |

| acetate | |

| Estradiol valerate | |

| Estradiol valerate/dienogest | |

| Estrone | |

| Estropipate | |

| Ethinyl estradiol/drospirenon | |

| Ethynodiol diacetate/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Levonorgestrel | |

| Levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate/estradiol | |

| cypionate | |

| Micronized progesterone | |

| Norelgestromin/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Norethindrone | |

| Norethindrone acetate/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Norethindrone acetate/ethinyl | |

| estradiol/ferrous fumarate | |

| Norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol/ferrous | |

| fumarate | |

| Norethindrone/mestranol | |

| Norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Norgestrel | |

| Norgestrel/ethinyl estradiol | |

| Progesterone | |

| Testosterone cypionate/estradiol cypionate | |

| Testosterone enanthate/estradiol valerate |

REFERENCES

- 1.Ballweg M. Impact of endometriosis on women’s health: comparative historical data show that the earlier the onset, the more severe the disease. Best Practice & Res Clin Obstetrics & Gynaecol. 2004;18(2):201-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benaglia L, Somigliana E, Vighi V, Nicolosi AE, Iemmello R, Ragni G. Is the dimension of ovarian endometriomas significantly modified by IVF–ICSI cycles? Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18(3):401-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo SW. Recurrence of endometriosis and its control. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15(4):441-61. Available at: http://humupd.oxfordjournals.org/content/15/4/441.long. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong C. ACOG updates guideline on diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(1):84-85. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0101/p84.html. Accessed March 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Streuli I, de Ziegler D, Santulli P, et al. An update on the pharmacological management of endometriosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14(3):291-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garry R. The effectiveness of laparoscopic excision of endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16:299-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valle RF, Sciarra JJ. Endometriosis: treatment strategies. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2003;997:229-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abbott JA, Hawe J, Clayton RD, Garry R. The effects and effectiveness of laparoscopic excision of endometriosis: a prospective study with 2-5 year follow-up. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(9):1922-27. Available at: http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/content/18/9/1922.long. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheong Y, Tay P, Luk F, Gan HC, Li TC, Cooke I. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis: how often do we need to re-operate? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(1):82-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tandoi I, Somigliana E, Riparini J, Ronzoni S, ViganÒ P, Candiani M. High rate of endometriosis recurrence in young women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24(6):376-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furnass S, Yap C, Farquhar C, Cheong YC. Pre and post-operative medical therapy for endometriosis surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD003678. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD003678.pub2/abstract;jsessionid=E7F891B3C3E08EADC73B8A698909060F.f03t01. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Fuldeore MJ, Marx SE, Chwalisz K, Smeeding JE, Brook RA. Add-back therapy use and its impact on LA persistence in patients with endometriosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(3):729-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Azemi M, Jones G, Sirkeci F, Walters S, Houdmont M, Ledger W. Immediate and delayed add-back hormonal replacement therapy during ultra long GnRH agonist treatment of chronic cyclical pelvic pain. BJOG. 2009;116(12):1646-56. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02319.x/full. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laufer MR. Current approaches to optimizing the treatment of endometriosis in adolescents. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;66(Suppl 1):19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hornstein MD, Surrey ES, Weisberg GW, Casino LA. Leuprolide acetate depot and hormonal add-back in endometriosis: a 12-month study. Lupron Add-Back Study Group. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91(1):16-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surrey ES, Hornstein MD. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(5 Pt 1):709-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez H, Lucas C, Hédon B, Meyer JL, Mayenga JM, Roux C. One year comparison between two add-back therapies in patients treated with a GnRH agonist for symptomatic endometriosis: a randomized double-blind trial. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(6):1465-71. Available at: http://humrep.oxfordjournals.org/content/19/6/1465.long. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu D, Hu M, Hong L, et al. Clinical efficacy of add-back therapy in treatment of endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2014;290(3):513-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug approval package. Lupaneta Pack. December 14, 2012. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/203696_lupaneta_toc.cfm. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- 20.Surrey ES, Voigt B, Fournet N, Judd HL. Prolonged gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment of symptomatic endometriosis: the role of cyclic sodium etidronate and low-dose norethindrone “add-back” therapy. Fertil Steril. 1995;63(4):747-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukherjee T, Barad D, Turk R, Freeman R. A randomized, placebo-controlled study on the effect of cyclic intermittent etidronate therapy on the bone mineral density changes associated with six months of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(1):105-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surrey ES. Add-back therapy and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in the treatment of patients with endometriosis: Can a consensus be reached? Add-Back Consensus Working Group. Fertil Steril. 1999;71(3):420-24. Available at: http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2898%2900500-7/fulltext. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truven Health Analytics. Marketscan Research Databases. 2012. Available at: http://truvenhealth.com/Portals/0/assets/ACRS_11223_0912_ MarketScanResearch_SS_Web.pdf. March 30, 2016.

- 24.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health. 2008;11(1):44-47. Available at: https://www.ispor.org/workpaper/research_practices/Cramer.pdf. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, Raggio G, Naujoks C. The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15(12):1003-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lupron Depot (leuprolide acetate for depot suspension) 3.75 mg and 3 month 11.25 mg. Abbvie. October 2013. Available at: http://www.endofacts.com/pi.aspx. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- 27.Rolnick SJ, Pawloski PA, Hedblom BD, Asche SE, Bruzek RJ. Patient characteristics associated with medication adherence. Clin Med Res. 2013;11(2):54-65. Available at: http://www.clinmedres.org/content/11/2/54.long. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zupi E, Marconi D, Sbracia M, et al. Add-back therapy in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(5):1303-03. Available at: http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282%2804%2902232-0/fulltext. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joo JK, Jung IK, Kim KH, Lee KS. Quality of life according to add-back therapy during GnRH agonist treatment in endometriosis patients. Korean J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55(6):371-77. Available at: http://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.5468/KJOG.2012.55.6.371&vmode=PUBREADER. Accessed March 30, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bulun SE. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):268-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chwalisz K, Surrey E, Stanczyk FZ. The hormonal profile of norethindrone acetate: rationale for add-back therapy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists in women with endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2012;19(6):563-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wheeler JM, Knittle JD, Miller JD. Depot leuprolide versus danazol in treatment of women with symptomatic endometriosis. I. Efficacy results. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167(5):1367-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuldeore M, Chwalisz K, Marx S, et al. Surgical procedures and their cost estimates among women with newly diagnosed endometriosis: a U.S. database study. J Med Econ. 2011;14(1):115-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas EJ, Peterson LA. Measuring errors and adverse events in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(1):61-67. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1494808/. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates DW, Evans RS, Murff H, Stetson PD, Pizziferri L, Hripcsak G. Detecting adverse events using information technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(2):115-28. Available at: http://jamia.oxfordjournals.org/content/10/2/115.long. Accessed March 30, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berket B, Taskin S, Aylin Taskin E. Complications of laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. In: Wetter PA, Kavic MS, Levinson CJ, et al., eds.. Prevention and Management of Laparoendoscopic Surgical Complications. 3rd ed. Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2012. Available at: http://laparoscopy.blogs.com/prevention_management_3/2010/07/complications-of-laparoscopicgynecologic-surgery.html. Accessed March 30, 2016.

- 38.Soderstrom RM. Injuries to major blood vessels during endoscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997;4(3):395-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim SM, Park EK, Jeung IC, Kim CJ, Lee YS, Abdominal, multi-port and single-port total laparoscopic hysterectomy: eleven-year trends comparison of surgical outcomes complications of 936 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(60):1313-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nazik H, Gul S, Narin R, et al. Complications of gynecological laparoscopy: experience of a single center. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2014;41(1):45-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumarkiri J, Kikuchi I, Kitade M, et al. Incidence of complications during gynecologic laparoscopic surgery in patients after previous laparotomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(4):480-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lam A, Kaufman Y, Khong SY, Liew A, Ford S, Condous G. Dealing with complications in laparoscopy. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;23(5):631-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]