Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality and is associated with substantial economic burden. There is a lack of data regarding COPD outcomes and costs in a real-world setting, particularly by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) severity.

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) characterize a commercially insured U.S. population with COPD and (b) assess prevalence of exacerbations, health care resource utilization (HCRU), costs, and treatment patterns in a cohort of patients with confirmed COPD, overall and stratified by GOLD stage.

METHODS:

This retrospective observational cohort study used administrative claims data from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database to identify patients with ≥ 1 inpatient, emergency room (ER), or office visit claim for COPD between January 1, 2012, and November 30, 2013, and continuous enrollment for 1 year before and 2 years after the first COPD diagnosis date. Patients with a spirometry claim within 12 months were eligible for medical record abstraction to confirm COPD diagnosis (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1]/forced vital capacity ratio < 0.7) and GOLD 1-4 classification (based on postbronchodilator FEV1 percent predicted). HCRU, costs, treatment patterns, and rate of moderate/severe exacerbation were identified from diagnosis up to 24 months. Outcomes were analyzed by univariate analysis stratified by GOLD classification. Multivariable analysis was conducted to assess associations between GOLD classification and outcomes of interest.

RESULTS:

53,484 patients newly diagnosed with COPD were identified who met initial inclusion criteria: 14,293 (27%) had a qualifying spirometry claim, and 1,505 had confirmed COPD (GOLD 1, 333 [22%]; GOLD 2, 823 [55%]; GOLD 3, 317 [21%]; GOLD 4, 32 [2%]). Patients with greater disease severity had higher rates of moderate/severe COPD exacerbations (GOLD 1 and 2, 40.4 and 48.9 per 100 person-years, respectively; GOLD 3 and 4, 83.6 and 89.1 per 100 person-years, respectively). All-cause and COPD-related inpatient admissions, COPD-related office visits, and COPD-related ER visits were more prevalent with more severe GOLD classification. Mean annual COPD-related medical costs increased with GOLD classification ($5,945 for GOLD 1 patients, $18,070 for GOLD 4). COPD maintenance medication was filled by 42%, 56%, 73%, and 75% of patients in GOLD 1-4 (57% overall), respectively; combination corticosteroid/long-acting beta2-agonist inhalers were the most commonly used medication, regardless of GOLD classification. Patients with more severe disease had greater adherence (range 44%-68% of days covered for GOLD 1-4) and persistence (range 107-209 days for GOLD 1-4).

CONCLUSIONS:

Trends toward increases in exacerbations, HCRU, and costs were observed as airflow limitation worsened. Adherence and persistence with COPD maintenance therapy was suboptimal even with severe disease.

What is already known about this subject

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is associated with high morbidity and mortality, as well as a significant health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs.

When patients are not treated appropriately, there is the potential for further increases in HCRU and cost as their disease worsens.

What this study adds

This study explored exacerbation rates and the economic burden and HCRU associated with COPD and identified areas where care at the time of this study may not have been in line with current recommendations and best practices, and where there may be potential for ongoing improvements.

A trend toward increases in exacerbations, HCRU, and costs was observed with higher Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease classification (more severe disease and airflow limitation).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung disease characterized by increasing airflow limitation. COPD is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, responsible for approximately 5% of deaths globally.1 Studies have also demonstrated substantial economic burden associated with COPD.2-4 The recent Continuing to Confront COPD International Patient Survey reported that in the United States annual direct costs associated with COPD were $9,981 per patient, with inpatient hospitalizations contributing to 33% of costs, and annual societal costs totaled $30,826 per patient.5 Exacerbations are an acute worsening of COPD symptoms, often leading to additional treatment, emergency room (ER) visits, or hospitalization, and are a major contributor to the economic burden of COPD.6 Hospitalization is typically the largest component of total costs associated with exacerbations, with cost highly correlated with exacerbation severity.6

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) strategy statement encourages the use of spirometry to confirm a clinical diagnosis of COPD via a postbronchodilator ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 0.7.7 From 2011 to 2016, the GOLD strategy recommended a long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) in combination with an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) as first-line maintenance therapy for patients with severe or very severe COPD.8 Beginning in 2017, the GOLD strategy recommended long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) or LABA treatment for patients requiring maintenance therapy and LAMA/LABA combination therapy for patients whose symptoms are not adequately controlled by monotherapy.9

Treatment with a LAMA may be superior to a LABA at preventing exacerbations,10 while LAMA/LABA combinations have demonstrated superiority to either monotherapy.11-13 Several studies have also shown LAMA/LABA to be superior to LABA/ICS at reducing exacerbations.14-16 In addition, LAMA/LABA is recommended over LABA/ICS due to the increased risk of pneumonia associated with long-term ICS use.7

Despite these recommendations, studies have revealed shortcomings in the clinical implementation of the GOLD strategy statement through the years. One study of U.S. patients presenting at ambulatory clinics revealed that only 54.7% of patients with COPD received treatment according to the current GOLD recommendations at the time.17 Similarly, only 19% of patients with COPD at a Veterans Administration Medical Center were appropriately treated based on guidelines, while 14% were overtreated, 44% were undertreated, and 23% were treated without following any guideline.18

Overall, there are limited data on COPD-associated outcomes and health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs in a real-world setting. In addition, few of these studies have assessed COPD outcomes by GOLD staging. To meet this need, this retrospective study characterized a commercially insured and Medicare Advantage U.S. population with COPD and assessed prevalence of exacerbations, HCRU, costs, and treatment patterns in the overall population, stratified by GOLD stage.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective observational cohort study used administrative claims and medical record data identified from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database (HIRD), a large, diverse collection of medical and pharmacy claims data from geographically distributed health plan members (both commercial and Medicare Advantage) across all 50 U.S. states.

Patients with at least 1 inpatient or ER claim with a primary diagnosis of COPD or at least 1 outpatient claim with a diagnosis of COPD in any position (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] diagnosis codes 491.x, 492.x, and 496.x) between January 1, 2012, and November 30, 2013 (patient identification period) were identified from the HIRD. The earliest service date during the patient identification period with a COPD diagnosis code was defined as the COPD diagnosis index date. The claims-based COPD population consisted of patients aged ≥ 40 years on the index date, with ≥ 12 months of continuous enrollment before the index date and free from any claim containing a COPD diagnosis code. For analysis of HCRU, costs, and treatment-pattern data, ≥ 24 months of continuous enrollment following the index date was required. This stipulation was not necessary for analysis of COPD exacerbations.

Patients with at least 1 claim for spirometry within 12 months before or following the index date were eligible for medical record abstraction. Obtained records were screened for the presence and completeness of spirometry results (screened medical record population). Patients from the screened medical record population with spirometry-defined COPD (FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7) formed the confirmed COPD population. Spirometry records were used to categorize patients by GOLD classification: GOLD 1, FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted (mild); GOLD 2, FEV1 ≥ 50% to < 80% predicted (moderate); GOLD 3, FEV1 ≥ 30% to < 50% predicted (severe); and GOLD 4, FEV1 < 30% predicted (very severe).8

All data use was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. An institutional review board waiver of authorization approval was obtained for abstracting clinical data, which was performed by trained medical record abstractors using a structured electronic data collection form.

COPD Exacerbations

Exacerbation events were identified from the index date until the end of the 24-month post-index study period. Moderate exacerbations were defined as a pharmacy claim for an oral corticosteroid or antibiotic filled ≤ 7 days from an office visit with a diagnosis code for COPD in any position (ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 491.xx, 492.xx, and 496.xx) or an ER visit with a primary diagnosis code for COPD. Severe exacerbations were defined as those for which inpatient admission occurred with a diagnosis code for COPD in the primary position. An exacerbation was recorded as a separate episode if it occurred following a 14-day period free of any exacerbation claim. Exacerbation claims occurring ≤ 14 days from another were counted as a single episode for which the most severe claim determined the severity. The end of the exacerbation period was defined by the latest date of the following: an office or ER visit, hospital discharge, or prescription fill plus a day’s supply. Each episode was followed by a 14-day period free of any claim that would qualify as a COPD exacerbation.

HCRU and Costs

All-cause and COPD-related hospitalizations, ER visits, office visits, and pharmacy claims and associated costs were measured until 24 months after the index date. All-cause claims were those containing an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code in any position for any condition. COPD-related claims were those containing a COPD diagnosis code in the primary position for inpatient admissions and ER visits or in any position for COPD-related office visits or other outpatient claims. Inpatient admissions were counted as readmissions if they occurred within 30 days (per current Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services guidance) or 90 days (to provide additional context) of another inpatient admission with an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for any condition and for COPD alone. Outpatient service claims containing an evaluation and management code for a physician office visit were used to distinguish outpatient office visits from other outpatient claims.

All-cause and COPD-related inpatient medical costs were calculated from facility and provider claims made during the inpatient admission. Medical costs for ER and office visits and other outpatient services were calculated from individual claims. Total medical costs were the sum of all outpatient service, office and ER visits, and inpatient admission costs. COPD-related pharmacy costs were the total costs for COPD rescue and maintenance medications. Maintenance medication was defined as LABA, LAMA, ICS, phosphodiesterase type 4 inhibitor, xanthine, ICS/LABA free combination or fixed-dose combination (FDC), LAMA/LABA free combination or FDC, short-acting muscarinic antagonist (SAMA)/short-acting beta-agonist (SABA) FDC, or LAMA/LABA/ICS free combination. Rescue medication was defined as SABA or SAMA. Total pharmacy costs were the sum of all pharmacy costs for medications for any condition. Total health care costs were the sum of the total medical costs and total pharmacy costs. Patient out-of-pocket expenses (e.g., deductibles, coinsurance, and copays) and health plan costs were included and adjusted to 2015 U.S. dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.19

Treatment Patterns

Treatment patterns were identified from pharmacy and medical claims via Generic Product Identifier codes and the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System and measured from the index date until the end of continuous coverage or the end of study. Prescriptions for COPD rescue or maintenance therapies were identified from the index date onwards; the earliest date of a filled prescription for maintenance medication was classified as the treatment index date.

Therapies of different classes filled within ≤ 30 days of one another with ≥ 30-day overlap in supply were defined as combination therapies. Therapies of a different drug class added to the regimen > 30 days after the initial treatment index date with a supply overlap of ≥ 30 days with the initial treatment were considered add-on therapies. The prescription fill date for this additional therapy was defined as the add-on date. Medications that were not refilled within 30 days of the supply end date (based on the previous prescription fill date) were considered treatment discontinuations. This analysis was also performed using a 60-day permissible gap. Therapy switch date was defined as the prescription fill date for a medication of a different class from the index therapy following treatment discontinuation.

Maintenance medication adherence was measured as the proportion of days covered from the treatment index date to the end of the follow-up period, with each day counted as a single day irrespective of the number of medications prescribed. Maintenance medication persistence was measured from the treatment index date to either treatment discontinuation or study end date. Treatment persistence was defined as the total number of days from the treatment index date to the final prescription fill date before discontinuation plus the number of days’ supply of medication provided at the final prescription fill. Medication persistence was assessed using a 30- and 60-day permissible gap in treatment. Adherence and persistence analyses were performed for all maintenance medication classes, as described above, that were started following diagnosis, including any changes to treatment during the study duration.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were COPD exacerbation rates, HCRU, and costs. The secondary outcome was treatment-pattern assessment.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses for this observational study were descriptive, and the results were reported as observed. All outcomes were analyzed by univariate analysis for the confirmed COPD population stratified by GOLD classification. All-cause and COPD-related HCRU and costs were annualized. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and/or Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Multivariable analysis was conducted to assess associations between GOLD classification and outcomes of interest in the confirmed COPD population. A negative binomial regression was used to estimate exacerbation rates and rate ratios. Survival analysis using a Cox proportional hazards regression was conducted to assess the association between GOLD classification and time to first exacerbation. A generalized linear model with negative binomial distribution and log link for count data was used to estimate HCRU. A generalized linear model with gamma distribution and log link was used to estimate and compare costs.

All analyses were adjusted for the following covariates: age on index date, sex, geographic region, health insurance type, setting of index COPD diagnosis (inpatient, ER, or outpatient), Elixhauser Comorbidity Index,20 smoking status, race/ethnicity, and any hospitalization before the index date.

Results

Study Populations and Demographics

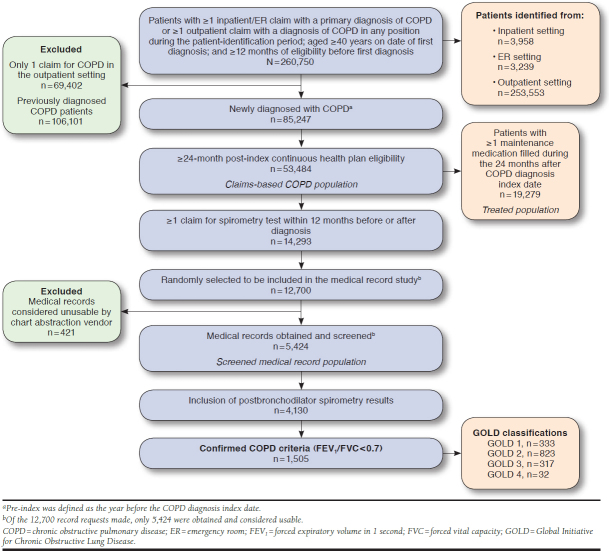

Within the HIRD, 260,750 patients were identified who met initial inclusion criteria (i.e., COPD diagnosis, age, and prediagnosis eligibility); 53,484 patients were newly diagnosed and comprised the claims-based COPD population (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the Confirmed COPD Population Generated from the HealthCore Integrated Research Database

Among the claims-based COPD population, 14,293 patients (27%) had a qualifying spirometry claim (Figure 1). Of these, 5,424 comprised the screened medical record population. Complete spirometry results including postbronchodilator results were available for 4,130 patients; 1,505 patients met the criteria for the confirmed COPD population. Within the confirmed COPD population, there were 333 GOLD 1 patients, 823 GOLD 2, 317 GOLD 3, and 32 GOLD 4. Due to the small sample size for GOLD 4, only GOLD 1-3 patients were included in the multivariable analysis models.

In the confirmed COPD population, 50% of patients were female, and the mean (± standard deviation [SD]) age was 69 (± 10.4) years (Table 1). The majority of patients were enrolled in a preferred provider organization (73%), with 33% enrolled in Medicare Advantage. Only 25% of patients saw a pulmonologist for treatment on the index date, but 65% received spirometry from a pulmonologist. Most patients had COPD diagnosed in the outpatient setting (95%), and 27% of patients also had a diagnosis of asthma.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Confirmed COPD Population Stratified by GOLD Stage

| GOLD 1 (n = 333) | GOLD 2 (n = 823) | GOLD 3 (n = 317) | GOLD 4 (n = 32) | Overall (N = 1,505) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 182 (54.7) | 397 (48.2) | 154 (48.6) | 20 (62.5) | 753 (50.0) |

| Mean ± SD age on index date, years | 70 ± 10.5 | 70 ± 10.7 | 67 ± 10.2 | 65 ± 8.7 | 69 ± 10.6 |

| Age group on index date, n (%) | |||||

| Aged 40-49 years | 14 (4.2) | 49 (6.0) | 15 (4.7) | 1 (3.1) | 79 (5.3) |

| Aged 50-64 years | 80 (24.0) | 164 (19.9) | 99 (31.2) | 14 (43.8) | 357 (23.7) |

| Aged 65+ years | 239 (71.8) | 610 (74.1) | 203 (64.0) | 17 (53.1) | 1,069 (71.0) |

| Health plan type, n (%) | |||||

| Health maintenance organization | 75 (22.5) | 187 (22.7) | 72 (22.7) | 9 (28.1) | 343 (22.8) |

| Participating provider organization | 238 (71.5) | 608 (73.9) | 233 (73.5) | 21 (65.6) | 1,100 (73.1) |

| Fee for service | 20 (6.0) | 28 (3.4) | 12 (3.8) | 2 (6.4) | 62 (4.1) |

| Insurance type, n (%) | |||||

| Medicare Advantage | 109 (32.7) | 265 (32.2) | 103 (32.5) | 15 (46.9) | 492 (32.7) |

| Commercial | 224 (67.3) | 558 (67.8) | 214 (67.5) | 17 (53.1) | 1,013 (67.3) |

| Treating provider specialty on index date, n (%) | |||||

| Family/general practice/internist | 127 (38.1) | 309 (37.6) | 123 (38.8) | 11 (34.4) | 570 (37.9) |

| Pulmonologist | 80 (24.0) | 219 (26.6) | 74 (23.3) | 8 (25.0) | 381 (25.3) |

| Nonphysiciana | 47 (14.1) | 124 (15.1) | 48 (15.1) | 3 (9.4) | 222 (14.8) |

| Other/missing | 79 (23.7) | 171 (20.8) | 72 (22.7) | 10 (32.1) | 332 (22.1) |

| Provider specialty on spirometry claim, n (%) | |||||

| Family/general practice/internist | 79 (23.7) | 167 (20.3) | 59 (18.6) | 11 (34.4) | 316 (21.0) |

| Pulmonologist | 216 (64.9) | 524 (63.7) | 215 (67.8) | 21 (65.6) | 976 (64.9) |

| Nonphysiciana | 18 (5.4) | 50 (6.1) | 13 (4.1) | 0 (0.0) | 81 (5.4) |

| Other/missing | 20 (6.0) | 82 (10.0) | 30 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 132 (8.8) |

| COPD diagnosis setting, n (%) | |||||

| Inpatient | 6 (1.8) | 25 (3.0) | 18 (5.7) | 3 (9.4) | 52 (3.5) |

| ER | 7 (2.1) | 12 (1.5) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (3.1) | 23 (1.5) |

| Outpatient | 320 (96.1) | 786 (95.5) | 296 (93.4) | 28 (87.5) | 1,430 (95.0) |

| Asthma diagnosis, n (%)b | 95 (28.5) | 222 (27.0) | 79 (24.9) | 9 (28.1) | 405 (26.9) |

| Smoking status, n (%)b | |||||

| Current smoker | 66 (19.8) | 225 (27.3) | 92 (29.0) | 9 (28.1) | 392 (26.1) |

| Former smoker | 172 (51.7) | 375 (45.6) | 146 (46.1) | 20 (62.5) | 713 (47.4) |

| Never-smoker | 49 (14.7) | 127 (15.4) | 42 (13.1) | 2 (6.3) | 220 (14.6) |

| Unknown/not documented | 46 (13.8) | 96 (11.7) | 37 (11.7) | 1 (3.1) | 180 (12.0) |

aNurse practitioners and physician’s assistants.

bCollected for the confirmed COPD population from the medical record.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ER = emergency room; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; SD = standard deviation.

Among GOLD 4 patients, 9.4% were diagnosed in an inpatient setting. Among GOLD 1 patients, 1.8% were diagnosed in this setting. See Appendix A (available in online article) for further demographics stratified by GOLD stage.

Comorbidities

The most common comorbidities were hypertension (63%), dyspnea (47%), asthma (27%), and ischemic heart disease (24%; Appendix A). GOLD 1 patients experienced more comorbidities that were likely to lead to an earlier diagnosis of COPD (e.g., dyspnea 51%, peptic ulcer 22%, allergic rhinitis 15%, lung cancer 4%); prevalence of these comorbidities declined as COPD severity at diagnosis increased. In GOLD 1 patients, 12% and 9% experienced depression and anxiety, respectively. Among GOLD 4 patients, these were experienced by 25% and 13%, respectively (Appendix A).

Moderate and Severe Exacerbations by GOLD Classification

Approximately half of all patients experienced at least 1 moderate or severe exacerbation in the 24 months following diagnosis (Table 2). Rates of COPD exacerbations for GOLD 1, 2, 3, and 4 patients were 40.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 35.8-45.4), 48.9 (95% CI = 45.6-52.4), 83.6 (95% CI = 76.7-90.9), and 89.1 (95% CI = 68.1-110.5), respectively, per 100 person-years. For GOLD 1, 2, and 3 patients, a similar trend was observed for rates of moderate and severe exacerbations, with approximately 30% of exacerbations in each GOLD classification falling into the severe category and approximately 70% falling into the moderate category. Prevalence of severe exacerbations was < 50% in all GOLD patients except those with GOLD 4 severity (56%; Table 2).

TABLE 2.

COPD Exacerbation Among the Confirmed COPD Population Stratified by GOLD Stage from Index Date to 24 Months Post-Index

| GOLD 1 (n= 333) | GOLD 2 (n = 823) | GOLD 3 (n = 317) | GOLD 4 (n = 32) | Overall (N = 1,505) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD time to first moderate/severe exacerbation, days | 140 ± 191 | 186 ± 214 | 172 ± 209 | 147 ± 182 | 173 ± 208 |

| Prevalence of moderate/severe exacerbations, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 199 (59.8) | 422 (51.3) | 109 (34.4) | 7 (21.9) | 737 (49.0) |

| 1 | 80 (24.0) | 225 (27.3) | 83 (26.2) | 7 (21.9) | 395 (26.3) |

| 2+ | 54 (16.2) | 176 (21.4) | 125 (39.4) | 18 (56.3) | 373 (24.8) |

| Prevalence of severe exacerbations, n (%) | 52 (15.6) | 172 (20.9) | 105 (33.1) | 18 (56.3) | 347 (23.1) |

| Prevalence of moderate exacerbations, n (%) | 105 (31.5) | 316 (38.4) | 168 (53.0) | 20 (62.5) | 609 (40.5) |

| Total exacerbation events per 100 person-years, crude rate (95% CI) | 40.4 (35.8-45.4) | 48.9 (45.6-52.4) | 83.6 (76.7-90.9) | 89.1 (68.1-110.5) | 55.2 (52.6-57.9) |

| Severe exacerbations | 12.0 (9.6-14.9) | 13.9 (12.3-15.9) | 25.4 (21.7-29.6) | 42.2 (28.4-60.5) | 16.5 (15.1-18.1) |

| Moderate exacerbations | 28.4 (24.5-32.7) | 34.9 (32.2-37.9) | 58.2 (52.5-64.4) | 46.9 (32.2-66.1) | 38.6 (36.5-40.9) |

CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; SD = standard deviation.

Exacerbation risk in GOLD 2 patients versus GOLD 1 patients was 1.23 (95% CI = 1.002-1.502). In GOLD 3 versus GOLD 1 patients, the exacerbation risk was 2.11 (95% CI = 1.673-2.657; Appendix B, available in online article).

HCRU and Costs by GOLD Classification

Overall, 44% of patients had at least 1 all-cause inpatient admission during the study period, and 32% of patients had at least 1 COPD-related inpatient admission (Table 3). All-cause inpatient admission was reported for 75% of GOLD 4 patients and 38% of GOLD 1 patients, while 72% of GOLD 4 patients and 23% of GOLD 1 patients experienced a COPD-related inpatient admission. The proportions of patients with 30-day all-cause readmissions were 21%, 16%, 21%, and 13%, while the proportions with 90-day all-cause readmissions were 31%, 22%, 31%, and 25% in the GOLD 1, 2, 3, and 4 groups, respectively.

TABLE 3.

Post-Index All-Cause and COPD-Related Annual HCRU and All-Cause and COPD-Related Annual Costs of the Confirmed COPD Population Stratified by GOLD Stage

| GOLD 1 (n = 333) | GOLD 2 (n = 823) | GOLD 3 (n = 317) | GOLD 4 (n = 32) | Overall (N = 1,505) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause HCRU | |||||

| Mean ± SD number of inpatient admissions, all patients | 0.35 ± 0.6 | 0.41 ± 0.7 | 0.48 ± 0.8 | 0.78 ± 1.0 | 0.42 ± 0.7 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 inpatient admission, n (%) | 128 (38.4) | 362 (44.0) | 150 (47.3) | 24 (75.0) | 664 (44.1) |

| Patients with 30-day readmission, n (%) | 27 (21.1) | 58 (16.1) | 32 (21.3) | 3 (12.5) | 120 (18.1) |

| Patients with 90-day readmission, n (%) | 39 (31.0) | 78 (21.8) | 47 (31.3) | 6 (25.0) | 170 (25.9) |

| Mean ± SD number of ER visits, all patients | 0.38 ± 0.9 | 0.34 ± 0.6 | 0.28 ± 0.5 | 0.38 ± 0.5 | 0.34 ± 0.6 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 ER visit, n (%) | 133 (39.9) | 303 (36.8) | 114 (36.0) | 14 (43.8) | 564 (37.5) |

| Mean ± SD number of office visits, all patients | 12.97 ± 8.4 | 12.64 ± 8.1 | 11.61 ± 7.4 | 11.44 ± 7.1 | 12.47 ± 8.0 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 office visit, n (%) | 333 (100.0) | 823 (100.0) | 317 (100.0) | 32 (100.0) | 1,505 (100.0) |

| COPD-related HCRU | |||||

| Mean ± SD number of inpatient admissions, all patients | 0.18 ± 0.5 | 0.22 ± 0.6 | 0.44 ± 0.9 | 0.72 ± 1.1 | 0.26 ± 0.5 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 inpatient admission, n (%) | 39 (11.7) | 135 (16.4) | 89 (28.1) | 16 (50.0) | 279 (18.5) |

| Patients with 30-day readmission, n (%) | 9 (23.1) | 9 (6.7) | 9 (10.1) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (9.7) |

| Patients with 90-day readmission, n (%) | 13 (33.3) | 13 (9.6) | 15 (16.9) | 1 (6.3) | 42 (15.1) |

| Mean ± SD number of ER visits, all patients | 0.09 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.12 ± 0.3 | 0.23 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.3 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 ER visit, n (%) | 35 (10.5) | 117 (14.2) | 57 (18.0) | 10 (31.1) | 219 (14.6) |

| Mean ± SD number of office visits, all patients | 1.93 ± 2.2 | 2.52 ± 2.2 | 3.56 ± 2.5 | 3.95 ± 2.8 | 2.64 ± 2.4 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 office visit, n (%) | 297 (89.2) | 771 (93.7) | 312 (98.4) | 31 (96.9) | 1,411 (93.8) |

| All-cause costs, all patients, $ | |||||

| Mean ± SD total medical costs | 22,217 ± 30,390 | 21,594 ± 30,484 | 22,520 ± 26,074 | 31,148 ± 30,165 | 22,130 ± 29,585 |

| Inpatient | 7,701 ± 19,042 | 7,042 ± 15,712 | 8,630 ± 18,799 | 14,430 ± 22,486 | 7,679 ± 17,350 |

| ER visits | 663 ± 1,987 | 418 ± 1,143 | 372 ± 787 | 747 ± 1,185 | 470 ± 1,326 |

| Office visits | 1,253 ± 852 | 1,217 ± 846 | 1,146 ± 752 | 1,050 ± 736 | 1,206 ± 826 |

| Other outpatient | 8,994 ± 14,746 | 9,106 ± 20,520 | 7,832 ± 11,934 | 10,354 ± 14,684 | 8,840 ± 17,686 |

| Pharmacy | 3,607 ± 7,172 | 3,811 ± 8,248 | 4,539 ± 7,893 | 4,567 ± 6,192 | 3,935 ± 7,908 |

| COPD-related costs, all patients, $ | |||||

| Mean ± SD total medical costs | 5,945 ± 13,370 | 6,978 ± 13,552 | 10,751 ± 14,553 | 18,070 ± 15,944 | 7,780 ± 13,956 |

| Inpatient | 3,853 ± 12,462 | 4,449 ± 12,728 | 6,277 ± 12,970 | 12,139 ± 15,599 | 4,865 ± 12,847 |

| ER visits | 186 ± 1,100 | 144 ± 588 | 193 ± 651 | 534 ± 1,059 | 172 ± 756 |

| Office visits | 198 ± 226 | 263 ± 254 | 373 ± 277 | 394 ± 318 | 275 ± 261 |

| Other outpatient | 1,116 ± 3,334 | 1,021 ± 1,447 | 1,908 ± 4,657 | 2,524 ± 3,364 | 1,261 ± 2,924 |

| Pharmacy costs | 592 ± 1,034 | 1,101 ± 1,624 | 2,000 ± 2,010 | 2,479 ± 2,418 | 1,207 ± 1,704 |

Note: Costs are displayed in U.S. dollars and were adjusted to 2015 U.S. dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index available from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ER = emergency room; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; HCRU = health care resource utilization; SD = standard deviation.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 all-cause ER visit ranged from 36% to 44% across GOLD groups. The proportion of patients with at least 1 COPD-related ER visit was 11% for GOLD 1 patients and 31% for GOLD 4 patients (Table 3).

All patients had at least 1 all-cause office visit during the study period. GOLD 1 patients had a mean (± SD) of 12.97 (± 8.4) all-cause office visits; among GOLD 4 patients, the mean (± SD) number of all-cause office visits was 12.47 (± 8.0). Mean (± SD) COPD-related office visits were 1.93 (± 2.2) among GOLD 1 patients and 2.64 (± 2.4) among GOLD 4 patients (Table 3).

The adjusted HCRU estimates obtained from the multivariable analysis were similar to the observed (unadjusted) results (Appendix B). The predicted number of COPD-related outpatient office visits was 3.63 (95% CI = 3.34-3.91) for GOLD 3, 2.51 (95% CI = 2.36-2.65) for GOLD 2, and 1.93 (95% CI = 1.70-2.15) for GOLD 1 (Appendix B).

Annual mean (± SD) all-cause total medical costs were $31,148 (± 30,165) among GOLD 4 patients, ranging from $21,594 (± 30,484) to $22,520 (± 26,074) among the other GOLD groups (Table 3). Mean (± SD) annual COPD-related total medical costs were $5,945 (± 13,370) for GOLD 1 patients and $18,070 (± 15,944) for GOLD 4 patients. Of these total medical costs, COPD-related inpatient costs were $3,853 (± 12,462) among GOLD 1 patients and $12,139 (± 15,599) among GOLD 4 patients (Table 3).

Adjusted total COPD-related cost estimates were similar to unadjusted costs. The predicted COPD-related total medical costs were $5,855 (95% CI = 4,506-7,227) for GOLD 1 patients and $11,119 (95% CI = 9,398-12,841) for GOLD 3 patients after controlling for covariates (Appendix B).

Treatment Patterns

The majority of patients (approximately 75%) across the GOLD classifications filled a COPD-related prescription during the 24-month period (Table 4). A COPD maintenance medication was filled by 42%, 56%, 73%, and 75% of patients in GOLD 1-4 (57% overall); across all GOLD classification groups, ICS/LABA FDC was used most frequently, while LAMAs were the most commonly used monotherapy. Triple therapy use was 20% in GOLD 3, 17% in GOLD 4 patients, and 5% and 9% among GOLD 1 and 2, respectively. In all, 67% of patients filled an ICS-containing medication (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Treatment Patterns in the Confirmed COPD Population Stratified by GOLD Stage, Adherence, Persistence, and Change in Therapy for Patients Taking Any COPD Maintenance Treatment in the Confirmed COPD Population Stratified by GOLD Stage, from Index Date to 24 Months Post-Index

| GOLD 1 (n = 333) | GOLD 2 (n = 823) | GOLD 3 (n = 317) | GOLD 4 (n = 32) | Overall (N = 1,505) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Patterns | |||||

| Any COPD medication, n (%) | 210 (63.1) | 608 (73.9) | 273 (86.1) | 31 (96.9) | 1,122 (74.6) |

| Any COPD maintenance treatment, n (%) | 143 (42.9) | 459 (55.8) | 231 (72.9) | 24 (75.0) | 857 (56.9) |

| Monotherapies | 66 (46.2) | 197 (42.9) | 87 (37.7) | 8 (33.3) | 358 (41.8) |

| LAMA | 42 (29.4) | 134 (29.2) | 65 (28.1) | 6 (25.0) | 247 (28.8) |

| LABA | 1 (0.7) | 12 (2.6) | 7 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (2.3) |

| ICS | 23 (16.1) | 43 (9.4) | 13 (5.6) | 2 (8.3) | 81 (9.5) |

| Xanthines | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.7) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (1.2) |

| Specific combination therapies | 75 (52.4) | 250 (54.5) | 132 (57.1) | 14 (58.3) | 471 (55.0) |

| ICS/LABA FDC | 68 (47.6) | 208 (45.3) | 85 (36.8) | 10 (41.7) | 371 (43.3) |

| LAMA/LABA FDC | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| LAMA/LABA/ICS free combination triple therapy | 7 (4.9) | 42 (9.2) | 46 (19.9) | 4 (16.7) | 99 (11.6) |

| Other combination therapies | 2 (1.4) | 12 (2.6) | 12 (5.2) | 2 (8.3) | 28 (3.3) |

| Rescue medications,a,b n (%) | 178 (53.5) | 517 (62.8) | 243 (76.7) | 29 (90.6) | 967 (64.3) |

| SABA | 166 (49.8) | 497 (60.4) | 236 (74.4) | 29 (90.6) | 928 (61.7) |

| SAMA | 24 (7.2) | 99 (12.0) | 59 (18.6) | 7 (21.9) | 189 (12.6) |

| SAMA/SABA FDC | 26 (7.8) | 84 (10.2) | 60 (18.9) | 9 (28.1) | 179 (11.9) |

| Oxygen therapy,a n (%) | 21 (6.3) | 100 (12.2) | 82 (25.9) | 16 (50.0) | 219 (14.6) |

| GOLD 1 (n = 143) | GOLD 2 (n = 459) | GOLD 3 (n = 231) | GOLD 4 (n = 24) | Overall (N = 857) | |

| Adherence, Persistence, and Change | |||||

| Mean ± SD overall medication adherence | |||||

| Proportion of days covered | 44 ± 29.1 | 53 ± 29.4 | 62 ± 30.2 | 68 ± 28.6 | 55 ± 30.1 |

| Among patients initiating on monotherapy | 41 ± 30.5 | 52 ± 30.3 | 65 ± 31.1 | 60 ± 34.3 | 54 ± 31.5 |

| Among patients initiating on combination therapy | 46 ± 27.9 | 54 ± 28.7 | 60 ± 29.6 | 73 ± 25.3 | 55 ± 29.2 |

| Mean ± SD overall medication persistence | |||||

| Time from initiation to discontinuation, 30-day permissible gap | 107 ± 112.5 | 144 ± 130.3 | 168 ± 135.3 | 209 ± 145.7 | 146 ±131.0 |

| Time from initiation to discontinuation, 60-day permissible gap | 143 ± 130.0 | 188 ± 141.6 | 215 ± 143.2 | 282 ± 132.0 | 191 ± 142.4 |

| First change in therapy, n (%) | |||||

| Add-on | 7 (4.9) | 44 (9.6) | 39 (16.9) | 4 (16.7) | 94 (11.0) |

| Switch | 1 (0.7) | 5 (1.1) | 8 (3.5) | 1 (4.2) | 15 (1.8) |

| Discontinuation of index treatment class (30-day permissible gap) | 122 (85.3) | 353 (76.9) | 152 (65.8) | 14 (58.3) | 641 (74.8) |

| Discontinuation of index treatment class (60-day permissible gap) | 115 (80.4) | 309 (67.3) | 128 (55.4) | 10 (41.7) | 562 (65.6) |

| Mean ± SD time to first change in therapy, days | |||||

| Add-on | 78 ±38.0 | 120 ± 99.5 | 118 ± 80.6 | 141 ± 150.2 | 117 ± 90.5 |

| Switch | 58 ± 0.0 | 57 ± 18.3 | 95 ± 100.5 | 55 ± 0.0 | 77 ± 74.4 |

| Discontinuation (30-day permissible gap) | 71 ± 67.4 | 89 ± 81.4 | 93 ± 84.6 | 113 ± 102.2 | 87 ± 80.5 |

| Discontinuation (60-day permissible gap) | 98 ± 94.8 | 112 ± 100.0 | 115 ± 106.7 | 166 ± 137.1 | 111 ± 101.4 |

aAssessed for any time during the post-index period regardless of proximity to maintenance medication initiation.

bUse was not mutually exclusive (i.e., a patient could have a fill of a SAMA/SABA FDC and a fill of a SAMA alone and be counted in each group).

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FDC = fixed-dose combination; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting beta2-agonist; LAMA = long-acting muscarinic antagonist; PDE4 = phosphodiesterase type 4; SABA = short-acting beta-agonist; SAMA = short-acting muscarinic antagonist; SD = standard deviation.

A large proportion of patients filled rescue medications, with 54% and 91% of GOLD 1 and GOLD 4 patients, respectively, filling rescue medications (Table 4). Oxygen use was reported in 6% of GOLD 1 and 50% of GOLD 4 patients, respectively.

Among the patients who received at least 1 maintenance medication during the study period, mean overall proportion of days covered for any maintenance medication was 44% among GOLD 1 patients and 68% among GOLD 4 patients. Mean (± SD) time from initiation to discontinuation (with a 30-day gap permissible) ranged from 107 (± 112.5) days to 209 (± 145.7) days for GOLD 1-4, respectively. The proportion of patients who discontinued treatment was 85% for GOLD 1 and 58% for GOLD 4 (Table 4).

Discussion

This retrospective study characterized a commercially insured and Medicare Advantage U.S. population with COPD to assess exacerbation rates, HCRU, cost of care, and treatment patterns stratified by GOLD stage.

Trends toward increasing HCRU and costs and exacerbation rate were generally seen with worsening disease severity in the confirmed COPD population, although inferential statistical analyses were not conducted in this study. These results correspond to other claims data studies that have shown a correlation between HCRU and costs with exacerbation and disease severity. Increasing COPD severity was associated with higher HCRU in patients with COPD from the U.S. National Health and Wellness Survey.21 In patients with COPD enrolled in Medicare Advantage, increasing exacerbation frequency was associated with a multiplicative increase in all-cause and COPD-related costs.22 Among patients with chronic bronchitis treated with COPD maintenance medications, the number of baseline exacerbations was a significant predictor of all-cause and COPD-related total costs.23

Despite the recommendation that spirometry be used to establish a diagnosis of COPD via a postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio < 0.7,8 only 27% of the claims-based COPD population had a claim for spirometry in the 12 months preceding or following the first COPD diagnosis. In addition, the majority of patients with spirometry results in their medical record were not confirmed to have COPD. This indicates that spirometry is significantly underused by physicians, who may instead rely on professional experience or on patients’ symptoms for diagnosis. Without spirometry to confirm diagnosis, physicians may misdiagnose COPD or underestimate disease severity. In a study of how primary care physicians’ opinions of COPD severity compared with spirometry-measured airflow obstruction, physicians’ COPD severity ratings before spirometry were accurate for only 30% of patients, and disease severity was underestimated in 41% of patients and often underestimated severity compared with patients’ self-assessment.24 Without spirometry, physicians are likely to underestimate or inadequately characterize COPD disease severity.

The majority of patients in this analysis were classified as GOLD 2; the rest were either GOLD 1 or GOLD 3, and only a small minority were GOLD 4. These results are similar to what has been reported for other U.S. and global populations of patients with COPD.25-27 GOLD 1 patients tended to be symptomatic with a high prevalence of dyspnea, an obvious phenotypic clinical presentation that may have contributed to early diagnosis. These patients also had numerous comorbidities, which may indicate they were seen regularly by their physicians, likely contributing to the high all-cause HCRU among GOLD 1 patients.

Only approximately 57% of all spirometry-confirmed patients with COPD had any maintenance therapy in the 24 months following diagnosis, indicating that many patients did not receive maintenance therapy. Of those who did, the majority (67%) received an ICS-containing treatment as the first maintenance therapy after diagnosis, most commonly ICS/LABA combination therapy. These treatment patterns are inconsistent with GOLD recommendations that were in place at the time of the study, which only advocated ICS use in patients with greater disease severity.8 This study showed that nearly half of GOLD 1 and 2 patients used ICS/LABA as COPD maintenance treatment, suggesting that physicians are not following these recommendations. Overprescribing of ICS has also been shown in several previous studies.28-31

By using medical and pharmacy claims data integrated with medical records from a large, geographically diverse commercial- and Medicare Advantage-insured population, this study has many strengths. The design allowed for evaluating HCRU before and after diagnosis without actively following patients. Another strength of using claims data was the ability to assign primary diagnosis in the inpatient and ER settings. Medical record data were abstracted to confirm COPD diagnosis, resulting in increased internal validity compared to a purely claims-based study.

Limitations

Despite these strengths, there were some limitations to the study. The data analyzed were from 2012 to 2013 to allow us to gather 2 years of data at the time of this study; it would be interesting to investigate this again with recent data from 2015 onwards. The Medicare population was represented using only Medicare Advantage members, who may not have necessarily reflected traditional Medicare members’ use patterns.

There was also a risk of potential coding errors in administrative claims and that providers may not have coded for spirometry tests. In addition, prescription claim dates may not have accurately reflected the beginning of treatment, and most inpatient-administered drugs were not recorded in claims data. It was also not possible to determine the primary reason for outpatient visits. Visits may have been routine follow-up or non-COPD related and not necessarily due to a COPD exacerbation, leading to potential overestimation; however, this was not expected to differ across groups. Furthermore, the nature of the study design posed a potential channeling bias related to the nature of physicians who had office-based spirometry compared with those who did not.

Finally, due to the descriptive and observational nature of this study, inferential statistical analyses were not performed, which limited the ability to draw conclusions from comparisons of variables across groups stratified by GOLD classification.

Clinical Implications

The study results have many potential clinical implications for treating patients with COPD in the real-world setting. Underuse of spirometry may contribute to underdiagnosis of COPD or underestimation of disease severity, potentially resulting in patients not receiving appropriate treatment. The finding that many patients were not receiving maintenance therapy also supports previous studies that suggest COPD is undertreated. The widespread treatment with ICS, inconsistent with GOLD recommendations, and poor treatment adherence and persistence offer opportunities for improving physician education and adoption of recommendations in clinical practice.

Conclusions

Trends toward increases in exacerbations, HCRU, and costs were observed with higher GOLD classification (more severe disease and airflow limitation). Persistence was low in patients with COPD receiving maintenance therapy, including among patients with the worst airflow limitation. At the time of data collection, spirometry rates were low, and a significant number of patients did not receive recommended maintenance therapy, with heavy use of ICS-containing regimens, regardless of GOLD classification. Overall, this study provides an exploration of exacerbation rates and the economic burden and HCRU associated with COPD in the real-world setting, highlighting areas where care at the time of this study may not have been in line with current recommendations and best practices, and where there may be potential for ongoing improvements.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Laura Badtke, PhD, of Complete HealthVizion, which was contracted and compensated by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals (Ridgefield, CT).

APPENDIX A. Pre-Index Clinical Characteristics of the Confirmed COPD Population Stratified by GOLD Stagea

| GOLD 1 (n = 333) | GOLD 2 (n = 823) | GOLD 3 (n = 317) | GOLD 4 (n = 32) | Overall (N = 1,505) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD Elixhauser Comorbidity Index | 2.8 ± 2.3 | 3.0 ± 2.3 | 2.7 ± 2.4 | 3.0 ± 2.4 | 2.9 ± 2.3 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 206 (61.9) | 538 (65.4) | 189 (59.6) | 21 (65.6) | 954 (63.4) |

| Dyspnea | 169 (50.8) | 391 (47.5) | 137 (43.2) | 10 (31.1) | 707 (47.0) |

| Asthma | 82 (24.6) | 234 (28.4) | 88 (27.8) | 8 (25.0) | 412 (27.4) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 80 (24.0) | 203 (24.7) | 65 (20.5) | 6 (18.8) | 354 (23.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 57 (17.1) | 170 (20.7) | 69 (21.8) | 3 (9.4) | 299 (19.9) |

| Peptic ulcer | 74 (22.2) | 137 (16.7) | 45 (14.2) | 4 (12.5) | 260 (17.3) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 50 (15.0) | 120 (14.6) | 35 (11.0) | 4 (12.5) | 209 (13.9) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 42 (12.6) | 106 (12.9) | 40 (12.6) | 3 (9.4) | 191 (12.7) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 39 (11.7) | 105 (12.8) | 30 (9.5) | 3 (9.4) | 177 (11.8) |

| Stroke | 42 (12.6) | 93 (11.3) | 36 (11.4) | 3 (9.4) | 174 (11.6) |

| Depression | 40 (12.0) | 86 (10.5) | 29 (9.2) | 8 (25.0) | 163 (10.8) |

| Anxiety | 30 (9.0) | 65 (7.9) | 31 (9.8) | 4 (12.5) | 130 (8.6) |

| Osteoporosis | 25 (7.5) | 73 (8.9) | 26 (8.2) | 3 (9.4) | 127 (8.4) |

| Renal disease | 30 (9.0) | 68 (8.3) | 24 (7.6) | 2 (6.3) | 124 (8.2) |

| Congestive heart failure | 24 (7.2) | 70 (8.5) | 29 (9.2) | 0 (0.0) | 123 (8.2) |

| Sleep apnea | 26 (7.8) | 71 (8.6) | 21 (6.6) | 1 (3.1) | 119 (7.9) |

| Chronic sinusitis | 32 (9.6) | 56 (6.8) | 20 (6.3) | 1 (3.1) | 109 (7.2) |

| Myocardial infarction | 10 (3.0) | 28 (3.4) | 16 (5.1) | 2 (6.3) | 56 (3.7) |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | 8 (2.4) | 20 (2.4) | 9 (2.8) | 1 (3.1) | 38 (2.5) |

| Lung cancer | 12 (3.6) | 17 (2.1) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (2.2) |

| Metabolic syndrome | 4 (1.2) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (0.6) |

aPre-index is defined as the year before the COPD diagnosis index date.

COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; SD = standard deviation.

APPENDIX B. Multivariate Analyses for COPD Exacerbations and Selected Health Care Use and Cost Parameters Among the Confirmed COPD Population

| Coefficient ± SE (95% CI) | Incidence Rate (95% CI) | Incidence Rate Ratios | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COPD exacerbation rates and rate ratiosa | ||||

| GOLD 1 | Reference | 0.686 (0.461-1.022) | Reference | |

| GOLD 2 | 0.205 ± 0.103 (0.002-0.407) | 0.842 (0.573-1.236) | 1.227 (1.002-1.502) | |

| GOLD 3 | 0.746 ± 0.118 (0.515-0.977) | 1.446 (0.968-2.160) | 2.108 (1.673-2.657) | |

| Coefficient ± SE (95% CI) | Predicted Number of Visits/Cost (95% CI) | |||

| All-cause inpatient hospital useb | ||||

| GOLD 1 | Reference | 0.36 (0.30-0.42) | ||

| GOLD 2 | 0.113 ± 0.102 (—0.088-0.313) | 0.41 (0.36-0.45) | ||

| GOLD 3 | 0.287 ± 0.123 (0.045-0.529) | 0.48 (0.40-0.56) | ||

| COPD-related inpatient hospital useb | ||||

| GOLD 1 | Reference | 0.20 (0.15-0.25) | ||

| GOLD 2 | 0.164 ± 0.137 (—0.105-0.434) | 0.24 (0.21-0.27) | ||

| GOLD 3 | 0.563 ± 0.150 (0.269-0.857) | 0.35 (0.29-0.41) | ||

| COPD-related ER useb | ||||

| GOLD 1 | Reference | 0.08 (0.04-0.13) | ||

| GOLD 2 | 0.136 ± 0.282 (—0.418-0.689) | 0.10 (0.08-0.11) | ||

| GOLD 3 | 0.408 ± 0.302 (—0.184-0.999) | 0.13 (0.09-0.16) | ||

| COPD-related outpatient office visit useb | ||||

| GOLD 1 | Reference | 1.93 (1.70-2.15) | ||

| GOLD 2 | 0.264 ± 0.066 (0.134-0.394) | 2.51 (2.36-2.65) | ||

| GOLD 3 | 0.633 ± 0.072 (0.491-0.774) | 3.63 (3.34-3.91) | ||

| COPD-related medical costsb | ||||

| GOLD 1 | Reference | $5,855 ($4,506-$7,227) | ||

| GOLD 2 | 0.16 ± 0.131 (—0.091-0.422) | $6,923 ($6,066-$7,781) | ||

| GOLD 3 | 0.639 ± 0.142 (0.362-0.917) | $11,119 ($9,398-$12,841) | ||

Note: GOLD 4 was excluded due to sample size < 100. Analyses were calculated from index date to 24 months after the index date and categorized by GOLD stage adjusted for covariates (n = 1,471). Covariates included age on COPD diagnosis index date (continuous and categorical), sex, race, geographic region, health insurance type (commercial, Medicare), setting of index COPD diagnosis (inpatient or outpatient), Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, smoking status, and any hospitalization in the pre-COPD diagnosis index date period.

aEstimated via negative binomial regression.

bEstimated via generalized linear model (with negative binomial distribution).

CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ER = emergency room; GOLD = Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; SE = standard error.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Fact sheet. November, 2016. Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs315/en/. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 2.Mannino DM, Higuchi K, Yu T-C, et al. Economic burden of COPD in the presence of comorbidities. Chest. 2015;148(1):138-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dang-Tan T, Ismaila A, Zhang S, Zarotsky V, Bernauer M. Clinical, humanistic, and economic burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Canada: a systematic review. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Souza AO, Shah M, Dhamane AD, Dalal AA. Clinical and economic burden of COPD in a Medicaid population. COPD. 2014;11(2):212-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foo J, Landis SH, Maskell J, et al. Continuing to Confront COPD International Patient Survey: economic impact of COPD in 12 countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toy EL, Gallagher KF, Stanley EL, Swensen AR, Duh MS. The economic impact of exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and exacerbation definition: a review. COPD. 2010;7(3):214-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2018. report. Available at: http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 8.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2011 report. 2011. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease . Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2017. report. Available at: http://goldcopd.org/gold-2017-global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd/. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 10.Vogelmeier C, Hederer B, Glaab T, et al. Tiotropium versus salmeterol for the prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(12):1093-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Noord JA, Aumann J-L, Janssens E, et al. Comparison of tiotropium once daily, formoterol twice daily and both combined once daily in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(2):214-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bateman ED, Ferguson GT, Barnes N, et al. Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 versus single bronchodilator therapy: the SHINE study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(6):1484-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buhl R, Maltais F, Abrahams R, et al. Tiotropium and olodaterol fixed-dose combination versus mono-components in COPD (GOLD 2-4). Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):969-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR, et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(23):2222-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beeh K-M, Derom E, Echave-Sustaeta J, et al. The lung function profile of once-daily tiotropium and olodaterol via Respimat® is superior to that of twice-daily salmeterol and fluticasone propionate via Accuhaler® (ENERGITO® study). Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:193-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogelmeier CF, Bateman ED, Pallante J, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily QVA149 compared with twice-daily salmeterol-fluticasone in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ILLUMINATE): a randomised, double-blind, parallel group study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):51-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharif R, Cuevas CR, Wang Y, Arora M, Sharma G. Guideline adherence in management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2013;107(7):1046-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foda HD, Brehm A, Goldsteen K, Edelman NH. Inverse relationship between nonadherence to original GOLD treatment guidelines and exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:209-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . Consumer Price Index. 2017. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm. Accessed December 14, 2018.

- 20.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dhamane AD, Witt EA, Su J. Associations between COPD severity and work productivity, health-related quality of life, and health care resource use: a cross-sectional analysis of national survey data. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(6):e191-e197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dhamane AD, Moretz C, Zhou Y, et al. COPD exacerbation frequency and its association with health care resource utilization and costs. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2609-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abudagga A, Sun SX, Tan H, Solem CT. Healthcare utilization and costs among chronic bronchitis patients treated with maintenance medications from a US managed care population. J Med Econ. 2013;16(3):421-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mapel DW, Dalal AA, Johnson P, Becker L, Goolsby Hunter A.. A clinical study of COPD severity assessment by primary care physicians and their patients compared with spirometry. Am J Med. 2015;128(6):629-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mapel DW, Dalal AA, Johnson PT, Becker LK, Hunter AG. Application of the new GOLD COPD staging system to a US primary care cohort, with comparison to physician and patient impressions of severity. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1477-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vestbo J, Vogelmeier C, Small M, Higgins V. Understanding the GOLD 2011 strategy as applied to a real-world COPD population. Respir Med. 2014;108(5):729-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoogendoorn M, Feenstra TL, Schermer TR, Hesselink AE, Rutten-van Mölken MP. Severity distribution of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Dutch general practice. Respir Med. 2006;100(1):83-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Drivenes E, Østrem A, Melbye H. Predictors of ICS/LABA prescribing in COPD patients: a study from general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Visentin E, Nieri D, Vagaggini B, Peruzzi E, Paggiaro P. An observation of prescription behaviors and adherence to guidelines in patients with COPD: real world data from October 2012 to September 2014. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(9):1493-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simeone JC, Luthra R, Kaila S, et al. Initiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the U.S. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:73-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White P, Thornton H, Pinnock H, Georgopoulou S, Booth HP. Overtreatment of COPD with inhaled corticosteroids: implications for safety and costs. Abstract 265 presented at: 6th IPCRG World Conference; April 25-28, 2012; Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]