Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Once-monthly and once-every-3-months long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of paliperidone palmitate (PP1M and PP3M, respectively) are available for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. However, information on the comparative effectiveness and costs of using these LAIs versus oral antipsychotics (OAs) is not available. The population effectiveness of using these treatments is also not known.

OBJECTIVE:

To project the effect of using PP1M and PP3M LAIs on psychiatric (Psych) and all-cause (AC) hospitalization rates over 18 months in patients with schizophrenia receiving Medicaid and treated with OAs.

METHODS:

A decision model, informed by data from 3 randomized controlled trials (PRIDE [NCT01157351], 3001 [NCT00111189], and 3012 [NCT01529515]), was developed to compare 3 strategies: (a) initiating OA and switching only to OA; (b) initiating with PP1M and continuing PP1M if the patient was stable at 6 months (or switching to OA if unstable; PP1M→PP1M); and (c) initiating with PP1M and switching to PP3M if the patient was stable at 6 months (or switching to OA if unstable; PP1M→PP3M). PRIDE data were used to inform the first 6-month outcomes; 3001 and 3012 data were used to inform outcomes in stable patients over the following 12 months. The primary outcome for this decision model study was Psych hospitalizations. AC hospitalizations and time to discontinuation were also assessed. Outcomes from each arm and time portions within an arm were reweighted to reflect the distribution of patient characteristics found in the real-world Medicaid sample with PRIDE trial inclusion/exclusion criteria applied. Several validation exercises were carried out to ensure that the reweighted results could reproduce observed outcomes in the Medicaid sample.

RESULTS:

Our final target real-world sample size was N=4,609. We found that in the Medicaid sample, compared with initiating treatments with OA, the PP1M→PP1M strategy was projected to produce a per patient decrease of 0.27 (95% CI = -0.43-0.97) and 0.28 (95% CI = -0.28-0.84) in Psych- and AC-related hospitalizations, respectively. Similarly, the PP1M→PP3M strategy was projected to produce a per patient decrease of 0.31 (95% CI = -0.27-0.87) in both Psych- and AC-related hospitalizations over OA. Validation exercises ensured that the reweighting methodology used could replicate observed outcomes in the Medicaid sample. These incremental reductions in hospitalization rates are worth about $3.4-$3.8 billion over an 18-month period in patients with schizophrenia receiving Medicaid.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our results suggest that using PP1M and PP3M treatment strategies for patients with schizophrenia receiving Medicaid could result in reduced hospitalizations. This finding, along with improvement to patients’ health, should be considered when assessing the value of these LAIs.

What is already known about this subject

The long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics paliperidone palmitate once-monthly (PP1M) and once-every-3-months (PP3M) formulations have shown efficacy in clinical trials of patients with schizophrenia; however, the population effectiveness of PP1M and PP3M is unknown.

Propensity-based methods can be used to project the real-world effect of a new therapy based on existing trial data, thereby providing valuable information to payers without conducting extensive and time-consuming research.

What this study adds

This is the first decision model to use PP1M and PP3M trial data to project the outcome of oral antipsychotic (OA)-treated patients if they switched to PP1M or PP1M→PP3M.

The projection was built on patient-level clinical trial data that were projected onto a Medicaid population.

Our results show that over an 18-month period, switching from OAs to PP1M or PP3M could produce substantial reductions in psychiatric- and all-cause-related hospitalizations.

Poor continuity of treatment is an ongoing challenge for individuals with schizophrenia, leading to relapse of symptoms and increased health care utilization.1 Because of their long pharmacokinetic half-lives, long-acting injectable (LAI) formulations of antipsychotic medications may help manage these challenges in some patients.1

In recent years, a number of LAIs have become available for patient use.1 However, information on the comparative effectiveness and costs of using these LAIs versus oral antipsychotics (OAs) is not available. The population effectiveness of using these treatments is also not known.

There is growing demand for evidence that any new health technology, whose efficacy is often established in controlled clinical trials, is effective when applied to the real world.2 This is especially true for payers, who are confronted with covering high costs for such technologies without evidence that plan beneficiaries will derive commensurate benefits from the technology.3 Public and private research is needed to generate such evidence, and several initiatives are under way to develop real-world data assets that can fill the gap (http://www.pcornet.org; http://apcdcouncil.org).

While traditional methods to generate real-world evidence are well established, such as pragmatic trial designs and observational data methods,4,5 they require significant time and resources. For example, the large pragmatic trials needed to produce real-world evidence can take several years,2 thereby delaying access to newer therapies. While generating such evidence is valuable for payers to make optimal decisions about access, real-world evidence could be projected from existing data for some therapies without having to conduct a new real-world study.6,7

The objective of this study was to develop a decision model, informed by patient-level data available from 3 randomized clinical trials with long-acting formulations of paliperidone palmitate (2 phase 3 trials and a limited real-world phase 3b study). These data were used to project the effect of using paliperidone palmitate once-monthly (PP1M) and once-every-3-months (PP3M) LAI formulations on psychiatric (Psych) and all-cause (AC) hospitalization rates over a period of 18 months in patients with schizophrenia receiving Medicaid and being treated with OAs. We monetized these effects using the potential size of the target population in Medicaid and the average costs of hospitalization.

Methods

Data Sources

Efficacy and effectiveness data for PP1M and PP3M were obtained from 3 different randomized controlled trials. The first trial, PRIDE (NCT01157351), was a 15-month prospective, real-world, randomized, comparative study of daily OAs (1 of the following 7 acceptable, prespecified OAs was used: aripiprazole, haloperidol, olanzapine, paliperidone, perphenazine, quetiapine, and risperidone) and PP1M in patients with schizophrenia who had recent involvement with the criminal justice system.5 The PRIDE study design incorporated both explanatory (efficacy) and pragmatic (effectiveness) design elements, allowing analysis of efficacy and effectiveness outcomes.5 The primary outcome measure was time to first treatment failure, the definition of which included arrest/incarceration, Psych hospitalization, or interventions to prevent treatment failure.

The second trial, 3001 (NCT00111189), was a randomized, double-blind, discontinuation relapse-prevention study that compared the efficacy and tolerability of PP1M to those of placebo among patients with schizophrenia who had been stabilized (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] total score ≤ 75) on PP1M for 3 months.8 The third trial, 3012 (NCT01529515), was a randomized, double-blind, relapse-prevention study that compared the efficacy and tolerability of PP3M with those of placebo among patients with schizophrenia who were stabilized (PANSS total score < 70) on PP1M for 4 months.9 The primary outcome measure for the latter 2 studies was time to first relapse during the double-blind phase, the definition of which included significant deterioration in clinical symptoms as measured by PANSS or hospitalization for symptoms of schizophrenia.

Real-world data for 2009 through 2013 were obtained from the Truven Multi-State Medicaid claims database. Inclusion and exclusion criteria from PRIDE (Appendix A, available in online article) were applied to identify OA-treated Medicaid beneficiaries in the Truven database. The main inclusion criteria included identifying patients who enrolled in Medicaid during 2009-2013, had at least 1 service with schizophrenia International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 295.xx within 90 days after enrollment, and had at least 1 antipsychotic prescription within 90 days of enrollment. We approximated data from the more real-world PRIDE population by including only those patients who initiated OA (index) within 90 days of enrollment in the Medicaid sample. As our decision model progressed, we mirrored the population targeted by trials 3001 and 3012 by identifying patients who were stabilized on OA for 6 months.

Decision Model

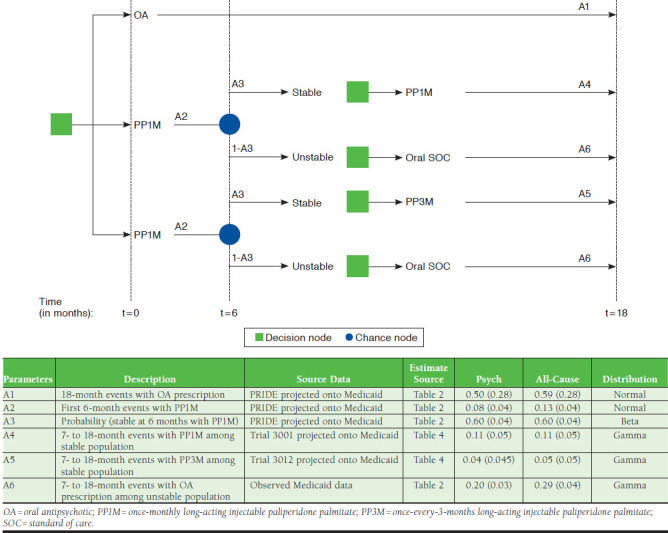

A decision model, informed by PRIDE, 3001, and 3012 trial data, was developed to compare 3 treatment strategies (Figure 1). The first treatment strategy was initiating with OA and switching to another OA. Because each index OA was not modeled separately, a weighted average of initiating with various index OAs (aripiprazole, haloperidol, olanzapine, paliperidone, perphenazine, quetiapine, or risperidone) was used (i.e., the weights were based on the observed distribution of use of these index drugs in the Medicaid sample). Treatment switches could be to any other OA, including long-acting drugs, provided that the long-acting drugs were not initiated 90 days before the index OA date.

FIGURE 1.

Decision Model

The second treatment strategy was initiating PP1M and continuing on PP1M if the patient was stabilized at 6 months (PP1M→PP1M). Those who discontinued PP1M within the first 6 months after initiation were switched back to receive OA. The remaining subjects continued to use PP1M. The third treatment strategy was initiating PP1M and switching to PP3M if the patient was stabilized at 6 months (PP1M→PP3M). Those who discontinued PP1M within the first 6 months after initiation were switched back to receive OA. The remaining subjects were switched to PP3M at the 6-month mark.

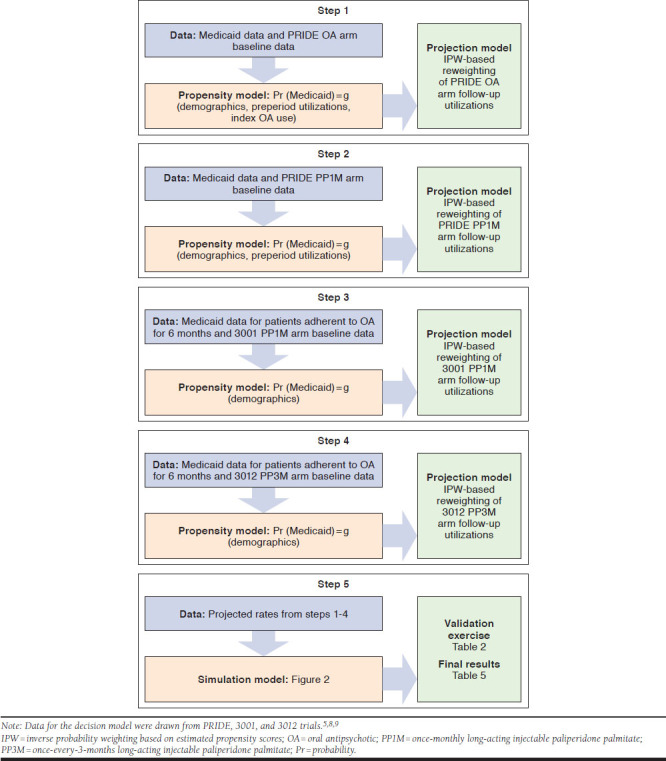

Statistical Analyses

Novel propensity score-based methods were used to assess the generalizability of PRIDE, 3001, and 3012 clinical trial data and extrapolate trial results to those of the Medicaid sample.10-13 Our analysis had 5 steps (Figure 2). The first step was to construct a propensity score model by comparing baseline characteristics of patients in the OA arm of the PRIDE trial versus those in the Medicaid sample and by calculating the probability of belonging to the Medicaid sample conditional on these baseline characteristics. The propensity score was based on age, gender, and race categories as well as preperiod time (time between enrollment and index date), use of Psych and AC hospitalizations during the preperiod time, and distribution of specific OAs used at initiation.

FIGURE 2.

Methodological Steps Followed to Generate Projection to Medicaid

The average number of trial-defined Psych and AC hospitalizations within 15 months of initiating an OA among patients in the PRIDE oral arm was reweighted with the inverse probability weighting (IPW), using the estimated propensity scores to project to those in the Medicaid sample who initiated OA. The 15-month projected estimates were prorated to reflect 18-month estimates and were compared with observed utilization rates of Psych and AC hospitalization of those in the Medicaid sample who initiated OA. A validation exercise was performed (see Validation Exercises section under this heading). Similar methods were used to reweight the probability of OA discontinuation observed in the PRIDE data to project the potential probability of OA discontinuation in the Medicaid population within the first 6 months of initiation.

The second step was to construct a second propensity score model that reflected the probability of belonging to a Medicaid cohort compared with the PP1M arm of the PRIDE trial. The propensity score was based on levels of age, gender, and race categories and on preperiod duration and utilization levels of Psych and AC hospitalizations during the preperiod time. Using IPW, the average number of Psych and AC hospitalizations within the first 6 months of receiving PP1M among patients enrolled in the PRIDE PP1M trial arm was projected to the Medicaid sample to reflect what the potential utilization rates would have been if the patients had initiated with PP1M. Similar methods were used to project the probability of PP1M discontinuation within the first 6 months of initiation.

The third step was to construct a third propensity score model reflecting the probability of belonging to Medicaid compared with the PP1M arm of trial 3001. Here, the Medicaid sample comprised those who would have continued their initial OA for at least 6 months, representing the stable population in trial 3001. The propensity score was based on levels of age, gender, and race categories. Using IPW, the average number of Psych and AC hospitalizations within the first 12 months of receiving PP1M among the stabilized patients in the PP1M arm of trial 3001 was projected to the stabilized patients in the Medicaid sample to reflect what the potential utilization rates would have been if they had initiated PP1M and continued receiving PP1M.

The fourth step was to construct a fourth propensity score model reflecting the probability of belonging to Medicaid compared with the PP3M arm of trial 3012. Here again, the Medicaid sample comprised those who would have continued their initial OA for at least 6 months; these patients represented the stable population in trial 3012. The propensity score was based on levels of age, gender, and race categories. Using IPW, the average number of Psych and AC hospitalizations within the first 12 months of receiving PP3M (i.e., patients in trial 3012 who were stabilized on PP1M for 6 months and then randomly assigned to PP3M) were projected to the stabilized patients in the Medicaid sample to reflect what the potential utilization rates would have been if they had initiated PP1M and continued receiving PP3M.

For steps 1 through 4, the modeling of utilizations accounted for censoring within corresponding trial data. Typically, IPW is used to account for censoring.14,15 However, because another set of weights was used for projection, a pattern mixture modeling approach was used to deal with censoring7,16; in this approach, a simple regression of utilization outcome on time to follow-up, the censoring indicator, and the interaction between these 2 approaches was used. Expected utilizations were estimated for 18 months (step 1), 6 months (in step 2), and 12 months poststabilization (steps 3 and 4) of follow-up.

The standard errors (SEs) for each projected parameter in our analyses were estimated based on 1,000 bootstrapped replicates on the corresponding analytical sample. All analyses were performed using Stata software package 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Probabilistic Simulation Model

Results from steps 1 through 4 were pooled in a fully probabilistic simulation model that compared 18-month utilization rates in the Medicaid sample for each of the 3 treatment strategies. The probabilistic simulation model incorporated all sources of uncertainty in parameter estimates. The distributional assumptions for each parameter are given in Figure 1.

The source of evidence for parameters A1 to A5 are given in Figure 1. We derived an estimate for parameter A6, which represents the 7- to 18-month utilizations among patients receiving OA who were unstable (i.e., discontinued their index medication within the first 6 months), based on observed Medicaid data (Figure 1). Differences between 18-month and 6-month utilizations in this group of unstable patients were defined as follows: (N = 4,609 × [1-0.39] = 2,795; AC: 1.01-0.72 = 0.29; Psych: 0.64-0.44 = 0.20). The SE for this derived parameter was based on 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

Validation Exercises

The first validation exercise compared propensity score-based projections of the PRIDE oral arm utilization data to the Medicaid sample with those of the observed utilization rates of Psych and AC hospitalizations in the Medicaid sample. Similarity in the projected and observed utilization rates confirmed the generalizability of these approaches to reflect outcomes in the Medicaid sample.

The second validation exercise compared the projected results from the PP1M→PP1M arm to the projected 18-month results from the PRIDE PP1M. Similarity between these results indicated replicability of the decision model results that combined information from various sources to that of a pragmatic trial when both sets of results were projected to reflect the Medicaid sample.

Quantification of Effect on Hospital Rates in U.S. Dollars

The monetary quantification of the effect of PP1M and PP3M treatment strategies on hospitalization rates was based on a total Medicaid population of 62 million and a cost of $10,000 per AC hospitalization.17,18 The target population was calculated by multiplying the exclusion rate in the Medicaid data used in this study (Appendix A; 4,609/232,016 = 1.98%) to the total Medicaid population. Therefore, monetization of hospitalization effect was calculated as the following:

$ = 62 million × 1.98% × $10,000 × reduction

in average number of hospitalizations

Results

The PRIDE inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the individual-level data from patients enrolled in Medicaid managed care between 2009 and 2013. Our final real-world sample size was 4,609 (Appendix A). Individual-level characteristics from the 2 arms (OA versus PP1M) of the PRIDE trial, the observed Medicaid data, and the projected characteristics of the PRIDE trial after reweighting aligned well with the Medicaid data (Appendix B, available in online article). Data from 212 PRIDE OA and 219 PRIDE PP1M patients were used to estimate the change in hospitalization outcomes for 4,609 Medicaid OA patients as if they had been treated with PP1M. Compared with PRIDE, the Medicaid sample was older (P < 0.010), more female and white (P < 0.001), and less black and Hispanic (Appendix B). Distribution of OA products differed significantly between PRIDE OA and Medicaid OA at index (P < 0.001).

Reweighting outcomes from PRIDE data to those of the Medicaid sample resulted in the average number of Psych hospitalizations at 18 months and 6 months to match closely with those observed in the Medicaid sample, thus validating the approach (Table 1). For AC hospitalization rates, reweighted estimates were lower than those in the Medicaid sample; this likely made our incremental estimate of long-acting paliperidone palmitate strategies a conservative one. Projected 6-month and 18-month absolute and incremental effects of PP1M are shown in Table 1. At 6 months, projected PRIDE PP1M mean Psych and AC hospitalizations per patient were estimated to be lower than projected PRIDE OA hospitalizations per patient by 0.30 (95% confidence interval [CI] = -0.01-0.61; SE = 0.16; P = 0.061) and 0.31 (95% CI = -0.02-0.64; SE = 0.17; P = 0.068), respectively. An additional 14% (95% CI = 2%-26%; SE = 6.0; P < 0.050) of this sample would have continued with medication at 6 months if treated with PP1M.

TABLE 1.

Projected Outcomes of PRIDE Trial Patients onto the Medicaid Patient Sample

| Outcomes | PRIDE Trial (Observed) a | Medicaid (Observed) a | PRIDE Trials (Projected) b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA n = 212 | PP1M n = 219 | Difference | P Value (95% CI) | OA n = 4,609 | OA n = 212 | PP1M n = 219 | Difference | P Value (95% CI) | |

| Hospitalizations over 18 months (full sample), n | |||||||||

| AC, mean (SE) | 0.55 (0.15) | 0.37 (0.09) | 0.18 (0.18) | 0.317 (-0.17-0.53) | 0.83(0.04) | 0.59 (0.28) | 0.40 (0.15) | 0.19 (0.32) | 0.552 (-0.43-0.82) |

| Psych, mean (SE) | 0.42 (0.15) | 0.22(0.07) | 0.20 (0.18) | 0.267 (-0.15-0.55) | 0.50 (0.03) | 0.50 (0.28) | 0.24 (0.09) | 0.26 (0.29) | 0.370 (-0.31-0.83) |

| Among patients who discontinued by 6 months | |||||||||

| AC, mean (SE) | – | – | – | 1.01 (0.05) | – | – | – | ||

| Psych, mean (SE) | – | – | – | 0.64 (0.06) | – | – | – | ||

| Hospitalizations over 6 months (full sample), n | |||||||||

| AC, mean (SE) | 0.42 (0.13) | 0.19 (0.05) | 0.23 (0.15) | 0.125 (-0.06-0.52) | 0.64 (0.02) | 0.44 (0.17) | 0.13(0.04) | 0.31 (0.17) | 0.068 (-0.02-0.64) |

| Psych, mean (SE) | 0.37 (0.13) | 0.11(0.04) | 0.26 (0.14) | 0.063 (-0.01-0.53) | 0.38 (0.03) | 0.38 (0.16) | 0.08(0.04) | 0.30 (0.16) | 0.061 (-0.01-0.61) |

| Among patients who discontinued by 6 months | |||||||||

| AC, mean (SE) | – | – | – | 0.72 (0.03) | – | – | – | ||

| Psych, mean (SE) | – | – | – | 0.44 (0.02) | – | – | – | ||

| Probability of continuation ≥ 6 months | 0.47 (0.03) | 0.59 (0.03) | -0.12(0.04) | 0.003 (-0.20-0.04) | 0.39 (0.01) | 0.46 (0.05) | 0.60(0.04) | -0.14 (0.06) | 0.020 (-0.02-0.26) |

| Time to discontinuation over 15 months, days | |||||||||

| Full sample, mean (SE) | 155 (13) | 245 (19) | -90 (23) | < 0.001 (45-135) | 149(7) | 153 (17) | 240 (23) | -87 (29) | 0.003 (-30-144) |

| Among patients who did not discontinue by 6 months, mean (SE) | – | – | – | 374 (6) | – | – | – | ||

| Time to discontinuation over 18 months, days | |||||||||

| Full sample, mean (SE) | – | – | – | 154(7) | – | – | – | ||

| Among patients who did not discontinue by 6 months, mean (SE) | – | – | – | 400 (6) | – | – | – | ||

Note: A dash means not enough sample size for estimation.

aAdjusted for censoring.

bAdjusted for censoring and projected to reflect the Medicaid sample; standard errors obtained via 1,000 bootstrap replicates.

AC = all-cause; CI = confidence interval; OA = oral antipsychotic; PP1M = once-monthly long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate; Psych = psychiatric; SE = standard error.

At 18 months, mean reductions in projected Psych and AC hospitalizations for PP1M compared with OA were 0.26 (95% CI = -0.31-0.83; SE = 0.29; P = 0.370) and 0.19 (95% CI = -0.43-0.82; SE = 0.32; P = 0.552), respectively. Median time to discontinuation over a 15-month duration in the PRIDE trial was projected to extend time on medication by 87 days (95% CI = 30-144; SE = 29; P = 0.003; Table 1) versus OA.

Table 2 illustrates how patient characteristics from the PP1M arm of trial 3001 and the PP3M arm of trial 3012 were made to reflect the distribution of characteristics in the Medicaid sample among the stable patients enrolled in these trials (i.e., those who continued their initial therapy for at least 6 months). Table 2 also presents the projected results from trials 3001 and 3012 to the stable Medicaid sample and reflect the projected utilizations for months > 6 through 18 or the 12-month poststabilization date.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients Stabilized on PP1M in Trial 3001a and Trial 3012b Projected on Those Receiving Medicaid Who Had ≥ 6 Months of Continued OA Therapy

| Characteristics | Observed | Medicaid n = 1,814 | Projected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial 3001 PP1M n = 160 | Trial 3012 PP3M n = 160 | Trial 3001 PP1M n = 160 | Trial 3012 PP3M n = 160 | ||

| Female, n (%) | 76 (47) | 42 (26) | 844 (47) | 74 (46) | 76 (48) |

| Age, years, mean (SE) | 37.3 (0.90) | 37.1 (0.86) | 41.4 (0.26) | 41.9 (0.84) | 41.8 (0.80) |

| White, n (%) | 108 (68) | 104 (65) | 1,034 (57) | 92 (57) | 94 (59) |

| Black, n (%) | 21 (13) | 24 (15) | 562 (31) | 50 (31) | 45 (28) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 13 (8) | 28 (17.5) | 36 (2) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Outcomes | Trial 3001 PP1M n = 160 | Trial 3012 PP3M n = 160 | Medicaid n = 1,814 | Trial 3001 PP1M n = 160 | Trial 3012 PP3M n = 160 |

| Hospitalizations per 12 months, n | |||||

| AC, mean (SE) | 0.10 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.04) | – | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.05 (0.05) |

| Psych, mean (SE) | 0.08 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.01) | – | 0.11 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.045) |

| 10th percentilec time to discontinuation over 12 months (SE) | 26 (5) | 84 (24) | – | 36 (25) | 85 (29) |

aIn trial 3001, 71.6% (681/951) of patients were stabilized at the end of the open-label phase, defined as those who received PP1M for at least 3 months and had PANSS total score ≤ 75 and selected PANSS item scores ≤ 4 (P1 [delusions], P2 [conceptual disorganization], P3 [hallucinatory behavior], P6 [suspiciousness/persecution], P7 [hostility], G8 [uncooperativeness], and G14 [poor impulse control]).

bIn trial 3012, 60.3% (305/506) of patients were considered stabilized at the end of the open-label phase, defined as those who received PP1M for at least 4 months and had a PANSS total score < 70 and selected PANSS item scores ≤ 4 (P1 [delusions], P2 [conceptual disorganization], P3 [hallucinatory behavior], P6 [suspiciousness/persecution], P7 [hostility], G8 [uncooperativeness], and G14 [poor impulse control]).

c10th percentile was chosen for this stabilized sample because 40% of the entire sample would discontinue before 6 months (Table 1).

AC = all-cause; OA = oral antipsychotic; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PP1M = once-monthly long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate; PP3M = onceevery-3-months long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate; Psych = psychiatric; SE = standard error.

Results of the probabilistic simulation model are shown in Table 3. In the Medicaid sample, the PP1M→PP1M strategy was projected to produce a per patient decrease of 0.27 (95% CI = -0.43-0.97) and 0.28 (95% CI = -0.28-0.84) in Psych- and AC-related hospitalizations, respectively, compared with initiating treatments with OA. Similarly, PP1M→PP3M was projected to produce a per patient decrease of 0.31 (95% CI = -0.27-0.87) in both Psych- and AC-related hospitalizations versus OA.

TABLE 3.

Probabilistic Decision Model Evaluating Outcomes Projected to Medicaid Sample Across 3 Treatment Strategies Over 18 Months

| Outcomes | OA | PP1M→PP1M | PP1M→PP3M | OA (PP1M→PP1M) Mean (SE), P Value (95% CI) | OA (PP1M→PP3M) Mean (SE), P Value (95% CI) | (PP1M→PP1M) (PP1M→PP3M) Mean (SE), P Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalizations | ||||||

| Psych, mean (SE) | 0.50 (0.28) | 0.23 (0.05) | 0.19 (0.05) | 0.27 (0.35), 0.440 (-0.43-0.97) | 0.31 (0.28), 0.268 (-0.43-0.97) | 0.04 (0.07), 0.568 (-0.10-0.18) |

| AC, mean (SE) | 0.59 (0.28) | 0.31 (0.05) | 0.28 (0.05) | 0.28 (0.28), 0.317 (-0.28-0.84) | 0.31 (0.28), 0.268 (-0.27-0.87) | 0.03 (0.07), 0.668 (-0.11-0.17) |

| Median time to discontinuation, days | 153 (17)a | 206 (24) | 265 (29) | – | – | -59 (38), 0.121 (-15-133) |

a> 15 months and so is not directly comparable to other estimates.

AC = all-cause; CI = confidence interval; OA = oral antipsychotic; Psych = psychiatric; PP1M = once-monthly long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate; PP3M = onceevery-3-months long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate; SE = standard error.

The absolute effect of the PP1M→PP1M strategy in our simulation was estimated to be 0.31 (95% CI = 0.21-0.41; SE = 0.05; P < 0.001) and 0.23 (95% CI = 0.13-0.33; SE = 0.05; P < 0.001) for AC- and Psych-related hospitalizations, respectively (Table 3). This matched well with the projected PRIDE results for the PP1M intention-to-treat arm of 0.40 (95% CI = 0.11-0.69; SE = 0.15; P = 0.008) and 0.24 (95% CI = 0.06-0.42; SE = 0.09; P < 0.001), respectively, and thereby validated our results. Only data from the first 6 months of the PRIDE trial were used in our simulation model; 7- to 18-month data were obtained from the other trials.

The incremental estimates reported in Table 3 were used to calculate potential savings for the total Medicaid population of 62 million.17 Based on our exclusion and inclusion criteria (Appendix A), the target sample size would be 1.23 million ([4,609/232,016] × 62 million). Assuming a cost of $10,000 per AC hospitalization, following the PP1M→PP1M strategy for 18 months would eliminate 344,400 AC hospitalizations amounting to $3.4 billion.18 Similarly, following the PP1M→PP3M strategy for 18 months would eliminate 381,300 AC hospitalizations amounting to $3.8 billion.

Discussion

Worldwide there is tremendous interest in real-world data and evidence in health care. However, conducting large studies to generate real-world evidence takes substantial time and resources. Therefore, obtaining signals from current clinical trial data on the projected and validated effect in real-world populations could be very useful. In this study, which was based on recent developments in reweighting methods, we projected the potential effect of patient-level data from 3 phase 3/3b clinical trials to reflect the real-world Medicaid population based on several patient characteristics. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to project a decision model drawing from different patient-level clinical trial data sources to those of a real-world population. We applied decision modeling to understand the potential real-world effect of using paliperidone palmitate LAIs over OAs in patients with schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia represents one of the most debilitating mental health illnesses in humans. Patients with this disorder are primarily treated with antipsychotic medications because of their efficacy in the treatment of delusions, hallucinations, mood instability, negative symptoms, and cognitive impairment1,19; this often results in significant functional improvement and a major public health benefit. A recent study by Fitch et al. (2014) estimated that in 2013 the average per patient per month cost of a patient with schizophrenia was $1,806,20 which translates to a total cost of $40 billion over 18 months in our target Medicaid population. Of the per patient per month cost of $1,806, 42% was based on inpatient expenditures.20 In a cost analysis study conducted by Wu et al. (2005), hospitalizations were found to be a major cost driver for patients with schizophrenia.21

Nonadherence to antipsychotic medication has been shown to account for 40% of relapses in schizophrenia, and nonadherent patients with schizophrenia are 2.5 times more likely to have a Psych hospitalization than those who are adherent.22-26 Successful care transition and continuous exposure to appropriate medication therapy are important factors that can help reduce the risk of relapse.27-29 However, in the 2008 CATIE study, 74% of study participants discontinued their study medication, and the median time to medication discontinuation was 4.6 months.30

Our results validate the CATIE study results and suggest that over an 18-month period, patients receiving OA discontinue medication after 153 days (5 months), whereas patients receiving PP1M→PP1M or PP1M→PP3M treatment experienced longer time to medication discontinuation (206 days and 265 days, respectively). Furthermore, during this 18-month period, switching from OA to PP1M or PP3M (with patients who fail to continue on PP1M or PP3M for 6 months switching back to OA) could produce substantial reductions in Psych and AC hospitalizations that are worth between $3.4 and $3.8 billion. This finding is particularly noteworthy given that schizophrenia is a costly disease.

A cost analysis based on private and public (Medicaid) claims databases found that the overall U.S. 2002 cost of schizophrenia was estimated to be $62.7 billion. Of this $62.7 billion, $22.7 billion was attributed to excess direct health care costs ($7.0 billion outpatient, $5.0 billion drugs, $2.8 billion inpatient, and $8.0 billion long-term care); $7.6 billion was attributed to direct nonhealth care excess costs; and $32.4 billion was attributed to indirect excess costs.21 Although cost reduction is important for reducing the economic burden of schizophrenia, perhaps more significant to the patient are the clinical benefits of continuous exposure to antipsychotic medication, which reduces the risk for relapse and its negative consequences, provides sustained symptom control, and optimizes clinical and psychosocial outcomes.31,32

Growing real-world evidence supports the premise that LAI antipsychotic use in routine clinical practice provides both clinical and economic benefits in patients with schizophrenia.33-37 Findings from recent claims database analyses and retrospective cohort studies have shown that, compared with OA, initiation of LAIs improves adherence and persistence, increases symptomatic remission, reduces treatment discontinuation, and decreases health care resource utilization and medical costs.33-37 In the PRIDE study, 95.2% of patients receiving PP1M had a medication possession ratio (MPR) of > 80% (based on injection records).5 This level of adherence was markedly higher than those receiving OA. By comparison, the proportion of OA patients with MPR > 80% was 77.2% when assessed with prescription records and 24.3% when assessed with refill records.5

In agreement with the results of our decision model study, a recent claims database analysis showed that LAI use is associated with significantly lower odds of rehospitalization (adjusted odds ratio = 0.73; 95% CI = 0.54-0.99; P = 0.041) compared with OA use.37 Although LAIs are associated with higher pharmacy costs, total costs are similar to OA,34 and the lower medical costs associated with second-generation LAIs, specifically PP1M, have been shown to offset more than one half of the higher pharmacy costs.35 Findings from these studies together with our observations further reinforce the notion that the clinical benefits of LAIs may also translate into meaningful reductions in economic burden.

Limitations

One limitation of our approach is the inherent reliance on observed and common patient characteristics between the trial and real-world data in order to project outcomes to the real world. Projecting based on some observed patient characteristics could be incomplete if there are differences in unobserved characteristics between the trial and the real-world sample that affect outcomes. Since there is no direct way to account for these unobserved characteristics, the comparison of projected outcomes from trials to observed outcomes in the real world can serve as a validation exercise. We performed 2 such validation exercises to show the credibility of our results.

Another major limitation is the integration of data from trials that had very different designs. For example, the 3001 and 3012 trials were global trials that were conducted in countries where service delivery was different from that in the United States. On the other hand, PRIDE was conducted in the United States as a long-term comparator study in patients who came from real-world settings. The requirement for a recent incarceration in PRIDE may have limited the generalizability of experience with this clinical trial population. However, our modeling data support the generalizability of those results despite differences in certain demographic characteristics.

Projecting trial results to a larger and more heterogeneous population increases uncertainty in the projection estimates. Our incremental effects—though substantial—did not reach statistical significance. However, the fact that we could replicate the point estimate of the PP1M strategy by projecting the full data from the PRIDE trial indicated that the real-world effect reported from our simulation model is less likely to be due to type I error. Our effect size indicates that long-term paliperidone palmitate strategies could save 1 hospitalization per 3 patients over an 18-month period, something we believe to be both clinically and economically important.

Based on this effect-size estimate, future studies would need sample sizes of more than 10,000 patients per arm to have the power to detect statistical significance. As adoption of these long-acting strategies improves, it would provide us with a large-scale, quasi-experimental opportunity to replicate the findings from this study.

Conclusions

Projection results suggest that using PP1M and PP3M treatment strategies for patients with schizophrenia receiving Medicaid could result in reduced hospitalizations. These findings, along with improvement to patients’ health, should be considered when assessing the value of these LAIs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mike Durkin of Janssen Scientific Affairs (Titusville, NJ) for contributing intellectually to the PRIDE data validation. The authors also thank Matt Gryzwacz, PhD, and Lynn Brown, PhD, of ApotheCom (Yardley, PA) for their writing and editorial support, which was funded by Janssen Scientific Affairs.

APPENDIX A. Identification of OA-Treated Medicaid Beneficiaries Following PRIDE Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Patients Excluded n (%) a | Patients Who Met Criteria n (%) a |

|---|---|---|

| Enrolled in Medicaid Managed Care, 2009-2013 | – | 232,016 (100) |

| Aged 18-60 years as of January 1, 2009 | 50,404 (22) | 181,612 (78) |

| Observed to enroll during 2009-2013 (i.e., to proxy release from incarceration) | 99,882 (55) | 81,730 (45) |

| Restrict enrollment dates from January 2009 through June 2012 so that individual could potentially have 18 months of enrollment | 12,719 (16) | 69,011 (84) |

| Remain enrolled for at least 3 months after first instance of enrollment during 2009-2013 | 839 (1) | 68,172 (99) |

| At least 1 service with schizophrenia ICD-9-CM code 295.xx within 90 days after enrollment | 35,987 (53) | 32,185 (47) |

| No ICD-9-CM code for opioid dependence within 90 days after enrollment | 916 (3) | 31,269 (97) |

| Any antipsychotic prescription within 90 days after enrollment | 24,943 (80) | 6,326 (20) |

| No clozapine within 90 days of index date for OA prescription | 146 (2) | 6,180 (98) |

| No injectable antipsychotics within 90 days of index date for OA prescription | 350 (6) | 5,830 (94) |

| No oral polytherapy on index date and days supply on oral monotherapy ≥ 15 days at index date | 1,221 (21) | 4,609 (79) |

aPercentage based on denominator of patients who met all previous criteria.

ICD-9-CM = International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; OA = oral antipsychotic.

APPENDIX B. Projected Characteristics of PRIDE Trial Patients onto the Medicaid Patient Sample

| Characteristics | PRIDE Trial (Observed) | Medicaid (Observed) | PRIDE Trial (Projected)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OA n = 212 | PP n = 219 | OA n = 4,609 | OA n = 212 | PP n = 219 | |

| Female, n (%) | 25 (12) | 33 (15) | 2,166 (47) | 85 (40) | 94 (43) |

| Mean age, years | 38.6 | 37.5 | 39.5 | 39.1 | 38.0 |

| White, n (%) | 70 (33) | 70 (32) | 2,258 (49) | 104 (49) | 88 (40) |

| Black, n (%) | 127 (60) | 140 (64) | 1,659 (36) | 76 (36) | 92 (42) |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 36 (17) | 31 (14) | 92 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5) |

| Baseline utilizations | |||||

| Mean AC hospitalizations | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.09 |

| Mean Psych hospitalizations | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| OA at index, n (%) | |||||

| Aripiprazole | 34 (16) | – | 784 (17) | 28 (13) | – |

| Haloperidol | 15 (7) | – | 507 (11) | 15 (7) | – |

| Olanzapine | 36 (17) | – | 645 (14) | 23 (11) | – |

| Paliperidone | 45 (21) | – | 277 (6) | 17 (8) | – |

| Perphenazine | 19 (9) | – | 46 (1) | 2 (1) | – |

| Quetiapine | 28 (13) | – | 1,290 (27) | 61 (29) | – |

| Risperidone | 36 (17) | – | 1,106 (24) | 66 (31) | – |

aProjected to reflect the Medicaid sample using inverse probability weighting.

AC = all-cause; OA = oral antipsychotic; PP = paliperidone palmitate; Psych = psychiatric.

REFERENCES

- 1.Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(Suppl 3):1-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alphs L, Schooler N, Lauriello J.. How study designs influence comparative effectiveness outcomes: the case of oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotic treatments for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Res. 2014;156(2-3):228-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu CY. Uncertainties in real-world decisions on medical technologies. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(8):936-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorpe KE, Zwarenstein M, Oxman AD, et al. A pragmatic-explanatory continuum indicator summary (PRECIS): a tool to help trial designers. CMAJ. 2009;180(10):E47-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alphs L, Benson C, Cheshire-Kenny K, et al. Real-world outcomes of paliperidone palmitate compared to daily oral antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia: a randomized, open-label, review board-blinded 15-month study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(5):554-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuart EA, Bradshaw CP, Leaf PJ.. Assessing the generalizability of randomized trial results to target populations. Prev Sci. 2015;16(3):475-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole SR, Stuart EA.. Generalizing evidence from randomized clinical trials to target populations: the ACTG 320 trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(1):107-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, Lim P, Morozova M, Eerdekens M.. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(2-3):107-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berwaerts J, Liu Y, Gopal S, et al. Efficacy and safety of the 3-month formulation of paliperidone palmitate vs placebo for relapse prevention of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):830-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imai K. Misunderstandings between experimentalists and observationalists about causal inference. J R Statist Soc A. 2008;171(part 2):481-502. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenhouse JB, Kaizar EE, Kelleher K, Seltman H, Gardner W.. Generalizing from clinical trial data: a case study. The risk of suicidality among pediatric antidepressant users. Stat Med. 2008;27(11):1801-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frangakis C. The calibration of treatment effects from clinical trials to target populations. Clin Trials. 2009;6(2):136-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisberg HI, Hayden VC, Pontes VP.. Selection criteria and generalizability within the counterfactual framework: explaining the paradox of antidepressant-induced suicidality? Clin Trials. 2009;6(2):109-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bang H, Tsaitis AA.. Estimating medical costs with censored data. Biometrika. 2000;87:329-43. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin DY. Linear regression analysis of censored medical costs. Biostatistics. 2000;1(1):35-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little RJA. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data. J Am Stat Assoc. 1993;88(421):125-34. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicaid managed care enrollment and program characteristics, 2014. Spring 2016. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-chip-program-information/by-topics/data-and-systems/medicaid-managed-care/downloads/2014-medicaid-man-aged-care-enrollment-report.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2018.

- 18.Pfuntner A, Wier LM, Elixhauser A.. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2011. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Statistical Brief #166. November 2013. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb166.pdf. Accessed May 26, 2018.

- 19.Bagnall AM, Jones L, Ginnelly L, et al. A systematic review of atypical antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7(13):1-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitch K, Iwasaki K, Villa KF.. Resource utilization and cost in a commercially insured population with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7(1):18-26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1122-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campagna EJ, Muser E, Parks J, Morrato EH.. Methodological considerations in estimating adherence and persistence for a long-acting injectable medication. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(7):756-66. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.7.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilmer TP, Dolder CR, Lacro JP, et al. Adherence to treatment with antipsychotic medication and health care costs among Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(4):692-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiden PJ, Mott T, Curcio N.. Recognition and management of neuroleptic noncompliance. In: Shriqui CL, Nasrallah HA, eds.. Contemporary Issues in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 1995:411-34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiden PJ, Zygmunt A.. Medication noncompliance in schizophrenia: part I, assessment. J Pract Psychiatr Behav Health. 1997;3:106-10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kane JM. Problems of compliance in the outpatient treatment of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:3-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Csernansky JG, Schuchart EK.. Relapse and rehospitalisation rates in patients with schizophrenia: effects of second generation antipsychotics. CNS Drugs. 2002;16(7):473-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Os J, Kapur S.. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):635-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panish J, Karve S, Candrilli SD, Dirani R.. Association between adherence to and persistence with atypical antipsychotics and psychiatric relapse among US Medicaid-enrolled patients with schizophrenia. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2013;4(1):29-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis S, Lieberman J.. CATIE and CUtLASS: can we handle the truth? Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(3):161-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Acosta FJ, Hemandez JL, Pereira J, Herrera J, Rodríguez CJ.. Medication adherence in schizophrenia. World J Psychiatry. 2012;2(5):74-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, Diez T, Granström O, De Hert M.. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3(4):200-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joshi K, Lafeuille MH, Brown B, et al. Baseline characteristics and treatment patterns of patients with schizophrenia initiated on once-every-three-months paliperidone palmitate in a real-world setting. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(10):1763-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joshi K, Lafeuille MH, Kamstra R, et al. Real-world adherence and economic outcomes associated with paliperidone palmitate versus oral atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia patients with substance-related disorders using Medicaid benefits. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7(2):121-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pilon D, Tandon N, Lafeuille MH, et al. Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization, and spending in Medicaid beneficiaries initiating second-generation long-acting injectable agents versus oral atypical antipsychotics. Clin Ther. 2017;39(10):1972-85.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson JP, Icten Z, Alas V, Benson C, Joshi K.. Comparison and predictors of treatment adherence and remission among patients with schizophrenia treated with paliperidone palmitate or atypical oral antipsychotics in community behavioral health organizations. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, Stoddard J, Doshi JA.. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(9):754-68. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.9.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]