Abstract

BACKGROUND:

It is estimated that acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) account for nearly 10% of hospital admissions and 3.4-3.8 million emergency department visits per year in the United States. Analyses of hospital discharge records indicate 74% of ABSSSI admissions involve empiric treatment with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) active antibiotics. Analysis has shown that payer costs could be reduced if moderate-to-severe ABSSSI patients were treated to a greater extent in the observational unit followed by discharge to outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT). Oritavancin is a lipoglycopeptide antibiotic with bactericidal activity against gram-positive bacteria, including MRSA.

OBJECTIVE:

To estimate the impact on a U.S. payer's budget of using single-dose oritavancin in ABSSSI patients with suspected MRSA involvement who are indicated for intravenous antibiotics.

METHODS:

A decision analytic model based on current clinical practice was developed to estimate the economic value of decreased hospital resource consumption by using single-dose oritavancin over a 1-year time horizon. Use of antibiotics was informed by an analysis of the Premier Research Database. Demographic and clinical data were derived from a targeted literature review. Emergency department, observation, laboratory, and administration costs used were Medicare National Limitation amounts. Drug costs were 2014 wholesale acquisition costs.

RESULTS:

For a hypothetical U.S. payer with 1,000,000 members, it is expected that approximately 14,285 members per year will be diagnosed with ABSSSI severe enough to indicate intravenous antibiotics with MRSA activity. Based on this simulation, use of single-dose oritavancin in 26% of these patients was estimated to reduce the number of inpatient admissions, reduce length of stay for patients requiring admission, and reduce the number of days a patient needs to receive daily infusions in the OPAT clinic. The total patient days decreased from 171,125 to 133,435 with a total annual budget impact of -$12,550,000 or -$1.05 per member per month (PMPM). Total inpatient and outpatient costs were reduced by $9,970,000 (19.7%) and $2,580,000 (4.2%), respectively. Inpatient cost savings were derived from a reduction in admissions, length of stay, and lower drug administration burden. Outpatient costs were reduced by lower drug administration burden in the OPAT setting. A sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the model was most sensitive to population estimates.

CONCLUSIONS:

Use of single-dose oritavancin in moderate-to-severe ABSSSI patients, including those with suspected MRSA, was projected to deliver an estimated cost reduction to U.S. payers of $1.05 PMPM by avoiding hospitalization in appropriate patients and reducing outpatient costs associated with multiday parenteral antibiotic therapy.

What is already known about this subject

Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection (ABSSSI) is a common diagnosis of patients seeking care at U.S. hospitals, and the treatment of patients can be costly for payers.

The ABSSSI treatment paradigm spans multiple treatment settings, where a patient often will incur inpatient costs and multiday ambulatory treatment costs.

Oritavancin is a newly approved single-dose, MRSA-active, intravenous antibiotic for treatment of ABSSSI patients.

What this study adds

This model presents payer costs across multiple settings of care, such as empiric treatment options; treatment-related decisions; and pharmacy, laboratory, and drug administration, providing a thorough representation of payer budget impact.

Model results indicate that adding oritavancin to a payer formulary could have a positive budget impact on inpatient and outpatient costs when simulating national practice patterns.

The impact of cost offsets with the use of lower health resource-consuming treatment options is highlighted.

In the United States, there are 3.4 million emergency department visits annually for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI).1 Eighty percent of these patients receive outpatient treatment, leading to 14.9 million ambulatory visits per year.2,3 The remaining 20% are treated as inpatients, making ABSSSI the cause of nearly 10% of all hospital admissions.4 Predominately caused by gram-positive pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, ABSSSI are now frequently due to methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).5 MRSA prevalence in ABSSSI ranges from 59% to as much as 74%, depending on geography.6 Left untreated or undertreated, MRSA infections can become life or limb threatening. As a result, when MRSA is suspected, ABSSSI are frequently empirically treated with MRSA-active antibiotics.

The high prevalence of MRSA in ABSSSI has led to high overall costs, estimated to be more than $6 billion per year for inpatient treatment alone.7 In response to pressures to contain or reduce health care spending, strategies have arisen to provide ABSSSI treatment entirely or partly in the outpatient

setting, including outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT).8 OPAT use is recommended in ABSSSI patients who are stable, compliant, and able to fully participate in, or have sufficient support to access, the delivery of care.9,10 Further, use of the observation unit for up to 47 hours followed by discharge to OPAT or oral therapy is increasingly being used as a strategy to avoid inpatient admissions.11-13

Whether inpatient or outpatient, the Infectious Diseases Society of America's recommended treatment course for patients with ABSSSI ranges from 5-14 days of systemic intravenous antibiotics.14-16 With the availability of OPAT, it is common for many ABSSSI patients to have 3-5 days as an inpatient and the remainder of care as an outpatient in either an ambulatory infusion center or at home.17 Because of the activity-based reimbursement system in the United States, health insurance companies often pay for the hospital admission and the daily accruing outpatient services to complete the course of therapy.

Recently, new drugs have been approved that require fewer doses and therefore may reduce the administrative burden and associated costs of treating ABSSSI. One such drug, oritavancin (ORBACTIV, The Medicines Company), is a lipoglycopeptide antibiotic with 3 mechanisms of actions that result in concentration-dependent bactericidal activity against gram-positive pathogens, including MRSA.18,19 Delivered as a once-only 1,200 mg intravenous (IV) dose, it has been demonstrated to be noninferior to twice-daily vancomycin for 7-10 days in patients with ABSSSI caused, or suspected to be caused, by gram-positive pathogens.20-22 A once-only therapy may be ideally suited to delivery in the outpatient setting, potentially allowing for more efficient and less costly treatment. The objective of this analysis was to quantify the budget impact, from a U.S. payer perspective, of using single-dose oritavancin for moderate-to-severe ABSSSI patients at risk of MRSA.

Methods

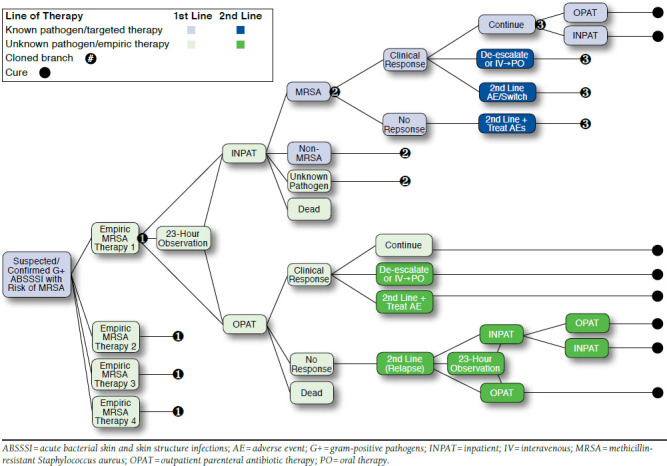

A decision analytic model based on current clinical practice was developed to simulate treatment of moderate-to-severe ABSSSI patients receiving empiric treatment with MRSA-active IV antibiotics (Figure 1). The perspective of the model was from a hypothetical U.S. payer with 1,000,000 members, and costs considered included the index treatment episode and 30-day ABSSSI-related rehospitalization. The decision tree was developed based on review of the literature and expert clinical opinion (authors Dufour, Nicolau, and Lodise).

FIGURE 1.

Decision Analytic Framework for ABSSSI Patient Management

Model Structure

As illustrated in Figure 1, ABSSSI patients entering the emergency department (ED) are treated with empiric MRSA-active therapy and may be cultured for pathogen confirmation and susceptibility testing. After receiving 1 dose of empiric therapy in the ED, patients may be treated in 1 of 3 settings: hospital inpatient, observation, or outpatient. Patients in any setting may either respond or not respond to first-line therapy. The model includes the following outcomes for responders: (a) continue empiric therapy; (b) de-escalate therapy (including either switching to non-MRSA active therapy, a less frequent dosing regimen, or oral therapy); or (c) switch therapy because of intolerance. Responders who de-escalate therapy were assumed to continue to respond. Nonresponders and patients who discontinue because of intolerance required switching to a second-line IV antibiotic, and these patients were assumed to be cured following second-line therapy. Patients who were placed under observation may progress to treatment as inpatients or be discharged for continued ambulatory treatment. Following clinical practice, admitted patients may complete their full course of therapy in the hospital, or they may be discharged to complete their treatment as outpatients. For patients discharged to outpatient treatment from the ED or from the observational unit, responders may continue to receive first-line therapy; de-escalate therapy (including either switching to non-MRSA active therapy, a less frequent dosing regimen, or oral therapy); or switch therapy because of intolerance. Nonresponding outpatients required switching therapy and could then become hospitalized or be kept as an outpatient, with or without a period of observation. Additionally, patients could experience an adverse event and incur associated costs. ABSSSI patients were followed through the treatment paradigm until 30 days after completion of therapy, and 30-day readmission rates specific to the final therapy were applied for all patient pathways. Table 1 lists the key clinical inputs used in the model. Table 2 provides details on second-line therapy use dependent upon first-line therapy and reason for therapy change.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Inputs

| Utilization Parameters | Oritavancin | Vancomycin | Linezolid | Daptomycin | Reference Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empiric treatment setting, % | 25, Expert opiniona | ||||

| Inpatient | 5.0 | 59.0 | 77.0 | 19.0 | |

| Outpatient | 15.0 | 35.0 | 16.0 | 80.0 | |

| Observation | 80.0 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 1.0 | |

| Final treatment setting, % | 24, Expert opiniona | ||||

| Inpatient | 5.0 | 26.0 | 28.0 | 35.0 | |

| Outpatient | 95.0 | 74.0 | 72.0 | 65.0 | |

| Empiric therapy utilization rate (base case), % | 25 | ||||

| 0.0 | 92.0 | 2.0 | 6.0 | ||

| Empiric therapy utilization rate (scenario), % | Expert opiniona | ||||

| 25.8 | 66.2 | 2.0 | 6.0 | ||

| Response rate, % | 27 | ||||

| MRSA | 74.5 | 76.0 | 83.0 | 68.4 | |

| Non-MRSA | 85.0 | 89.0 | 90.0 | 94.3 | |

| Unknown pathogen | 82.9 | 82.2 | 87.4 | 90.2 | |

| Mortality, % | 20, 21, 25, 37 | ||||

| MRSA | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Non-MRSA | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Unknown pathogen | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| AE discontinuation, % | 15, 36, 38 | ||||

| 0.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 | 2.8 | ||

| De-escalation, % | Expert opiniona | ||||

| MRSA | 0.0 | 49.4 | 10.4 | 51.3 | |

| Non-MRSA | 0.0 | 57.2 | 88.2 | 0.0 | |

| Unknown pathogen | 0.0 | 39.7 | 34.2 | 43.1 | |

| 30-day ABSSSI-related readmission rate, % | 39-42 | ||||

| 1.6 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.2 | ||

| AE rates, % | 15, 16, 20-22 | ||||

| Elevated CPK | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.8 | |

| Myelosuppression | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.5 | 0.0 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Phlebitis | 0.0 | 9.2 | 4.5 | 4.3 | |

| Rash/pruritus | 3.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 4.5 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 7.3 | 7.6 | 5.0 | 5.2 | |

| Diarrhea | 3.7 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 0.0 | |

| Constipation | 3.4 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 2.4 |

aExpert opinion from authors Dufour, Nicolau, and Lodise.

ABSS1 = acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections; AE = adverse event; CPK = creatine phosphokinase; MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

TABLE 2.

Second-Line Therapy Utilization Inputs

| Second-Line Treatment Mix, % | Initial Empiric Therapy | Reference Source | |||

| Vanc | Lin | Dap | Ori | ||

| Inpatient: Switch due to AE or nonresponse | |||||

| Vancomycin IV | 0.0 | 74.0 | 93.0 | 68.0 | 20, 25 |

| Linezolid IV | 22.0 | 0.0 | 7.0 | 20.0 | 20, 25 |

| Daptomycin IV | 78.0 | 26.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 20, 25 |

| Oritavancin IV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Expert opiniona |

| Inpatient: De-escalation of therapy | |||||

| Linezolid PO | 14.0 | 73.0 | 28.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Oritavancin IV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | Expert opiniona |

| Daptomycin IV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole PO | 40.0 | 13.0 | 36.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Doxycycline PO | 23.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Clindamycin PO | 23.0 | 2.0 | 24.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Outpatient: Switch due to AE or nonresponse | |||||

| Vancomycin IV | 0.0 | 74.0 | 93.0 | 68.0 | 20, 25 |

| Linezolid IV | 22.0 | 0.0 | 7.0 | 20.0 | 20, 25 |

| Daptomycin IV | 78.0 | 26.0 | 0.0 | 12.0 | 20, 25 |

| Outpatient: De-escalation of therapy | |||||

| Linezolid PO | 14.0 | 73.0 | 28.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole PO | 40.0 | 13.0 | 36.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Doxycycline PO | 23.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

| Clindamycin PO | 23.0 | 2.0 | 24.0 | 0.0 | 20, 25 |

aExpert opinion from authors Dufour, Nicolau, and Lodise.

AE = adverse event; Dap = daptomycin; IV = intravenous; Lin = linezolid; Ori = oritavancin; PO = oral therapy; Vanc = vancomycin.

Analysis Scenarios

The following 2 oritavancin use scenarios were considered in this analysis.

Outpatient Use Scenario.

The first scenario explored in the model examined current standard of care practice (mix of inpatient and outpatient treatment for ABSSSI) compared with the introduction of oritavancin use in the outpatient setting. Standard of care practice was derived from analysis of the Premier Research Database. The Premier Research Database is geographically representative of the United States and includes data for approximately 1 out of every 5 hospital discharges nationally. Based on inputs from medical experts, a list of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes was selected that represent ABSSSI and are in line with recently published U.S. Food and Drug Administration trial design guidance.23 Patients were included for analysis if they had a primary diagnosis of 1 of the following ICD-9-CM codes and an IV MRSA-active antibiotic prescription: 035 (erysipelas); 681.x and 682.x (cellulitis/abscess); 686.8 and 686.9 (other specified/unspecified local infections of skin and subcutaneous tissue); 958.3 (post-traumatic wound infection); and 998.5x (post-operative infections).

Analysis of the database provided insight into use of IV antibiotics for ABSSSI patients presenting to the ED and receiving MRSA-active antibiotics. It was found that 92% of patients receive IV vancomycin; 6% receive IV daptomycin; and 2% receive IV linezolid. In the scenario case, oritavancin was assumed to be used in 26% of patients, displacing vancomycin and representing those patients with moderate-to-severe ABSSSI.2,10,24 Use of other antibiotics remained identical to the base case (Table 1).

Oritavancin use in this scenario was assumed to be primarily in the outpatient setting. Based on expert opinion (authors Dufour, Nicolau, and Lodise) on how a single-dose therapy might be implemented, this scenario assumed that 80% of oritavancin patients were treated using observation followed by discharge; 15% of patients were treated in the ED only followed by discharge; and 5% of patients treated with oritavancin were initially admitted to the hospital as inpatients. Treatment settings for comparator antibiotics were derived from analysis of the Premier Research Database as previously described and are listed in Table 1. Use of inpatient setting ranged from 19%-77%, depending on initial antibiotic therapy choice.

Inpatient Use Scenario.

The second scenario was developed to consider the budget impact of oritavancin administered in the inpatient setting. In this scenario, we compared the use of vancomycin initially administered in the inpatient setting followed by discharge with OPAT with inpatient administration of oritavancin and subsequent patient discharge to home. Analysis of the Premier Research Database indicated that the average length of stay (LOS) for patients receiving vancomycin with subsequent discharge to OPAT is 4.1 days. Patients then receive an average of 6.1 days of OPAT treatment following discharge.25,26 This led to a ratio of inpatient days to total duration of therapy of 0.4. Applying this ratio to oritavancin would lead to the unrealistic assumption of 0.4 days of inpatient stay. Therefore, the model assumed that the average LOS for oritavancin patients admitted to the hospital is 2.5 days. This was determined to be enough time to allow the treating physician to ensure that a patient responded to therapy before discharging the patient to home, since no additional OPAT therapy is needed following administration of the single dose of oritavancin.

Clinical Inputs

Clinical inputs were obtained from a systematic literature review and network meta-analysis, described elsewhere.27 In brief,

EMBASE, MEDLINE, MEDLINE in Process, and CENTRAL

(Cochrane) were searched from inception to January 1, 2014, for randomized controlled trials investigating antimicrobial agents for the treatment of ABSSSI. A total of 52 trials were identified, with vancomycin and linezolid the most frequently reported. A Bayesian indirect treatment effects was utilized to determine the comparative efficacy point estimates for MRSA infections, non-MRSA infections, and for unknown infections for multiple antibiotics including vancomycin, linezolid, dapto-mycin, oritavancin, and others. Probabilities were derived from the logarithm of the odds ratios using the following equation:

P = exp(lodds)/1+exp(lodds)

Discontinuation, relapse, and adverse events (AEs) were not reported separately by pathogen type, so a single estimate informed from the literature search was used for each drug across all pathogen types (Table 1).

Economic Inputs

Direct health care costs incurred by the payer for the inpatient and outpatient settings were included in the model. Because payment rates for commercial and Medicaid payers are not publicly available, Medicare costs were used for economic inputs. Inpatient costs were based on the fiscal year 2014 final rule tables for national operating base rate and adjusted for the relative weighting factors for Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG) rates for ABSSSI patients (DRG 602, 603, 856, 857, 858, 862, and 863) admitted to the hospital.28 DRG rates are, by default, all-inclusive of ward, drug, laboratory/monitoring, AE, and procedural costs. The mix of DRG rates was based on discharges that were determined from analysis of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) National Inpatient Sample, a large dataset of about 8 million inpatient discharges from about 1,000 hospitals (Table 3).29

TABLE 3.

Key Health Resources and Economic Inputs

| Parameters | Value | Reference Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Health Resource Inputs | ||

| Average days of treatment | 25, Expert opiniona | |

| Oritavancin I V | 1.0 | |

| Vancomycin IV | 10.18 | |

| Linezolid IV | 13.72 | |

| Daptomycin IV | 11.06 | |

| Linezolid PO | 13.72 | |

| Outpatient mix, % | 25 | |

| Infusion center | 80.0 | |

| Home health care | 20.0 | |

| Outpatient infusion center mix, % | Expert opiniona | |

| Hospital outpatient | 90.0 | |

| Freestanding infusion clinic | 10.0 | |

| DRG mix, % | 29 | |

| DRG 602 | 8.0 | |

| DRG 603 | 72.0 | |

| DRG 856 | 2.0 | |

| DRG 857 | 4.0 | |

| DRG 858 | 1.0 | |

| DRG 862 | 4.0 | |

| DRG 863 | 9.0 | |

| Economic Inputs | ||

| DRG rate, $ | 28 | |

| DRG 602 | 7,844.37 | |

| DRG 603 | 4,512.11 | |

| DRG 856 | 25,709.68 | |

| DRG 857 | 10,961.82 | |

| DRG 858 | 7,043.12 | |

| DRG 862 | 10,151.44 | |

| DRG 863 | 5,287.04 | |

| Emergency department cost, $ | 43 | |

| ED visit (APC 0616) | 455.93 | |

| Observation unit cost, $ | 43 | |

| Observation stay, per diem (APC 8009-APC 616) | 742.98 | |

| IV drug cost (J code), $/mg | 28, Medi-Span Price Rx | |

| Vancomycin (J3370) | 2.18/500 | |

| Linezolid (J2020) | 45.66/200 | |

| Daptomycin (J0878) | 0.67/1 | |

| Oritavancin (J2407) | 2,736/1,200 | |

| Laboratory cost per test, $ | 43 | |

| Chem7 | 11.54 | |

| CBC levels | 10.61 | |

| CPK levels | 8.88 | |

| Drug trough levels | 18.49 | |

| Hepatic panel | 11.14 | |

| Other costs, $ | 43 | |

| PICC line initial placement, (APC 0621) | 849.71 | |

| X-ray to confirm placement (CPT 71010) | 24.00 | |

| Infusion center costs, $ | 43 | |

| IV infusion costs, inital hour (APC 0439) | 172.18 | |

| IV infusion costs, each subsequent hour (CPT 99602) | 29.50 | |

| IV bolus push costs, 2-minute bolus (CPT 96374) | 105.90 | |

aExpert opinion from authors Dufour, Nicolau, and Lodise.

APC = Ambulatory Payment Classification; CBC = complete blood count; CPK = creatine phosphokinase; CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; DRG = Diagnosis-Related Groups; ED = emergency department; IV = intravenous; PICC = peripherally inserted central catheter; PO = oral therapy.

Outpatient costs were estimated for patients who received all or some of their treatment in the outpatient setting and included activities involving ED, observation unit, drug, laboratory, AE, and administration costs for hospital infusion centers, freestanding infusion centers, and home health care. IV drug payments were based on Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes, calculated using the average sales price + 6.0%.28 Oral drugs were assumed to be paid through the retail pharmacy benefit; therefore, the 2014 wholesale acquisition costs were used as the estimated payer cost (Medi-Span Price Rx, Indianapolis, IN). The 2014 Medicare national limit rates were used as costs for hospital ED and drug administration and monitoring activities based on their respective Current Procedural Terminology or Ambulatory Payment Classification codes (Table 3). All costs are reported in 2014 U.S. dollars; costs were inflated to 2014 values, where necessary, using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.30

Sensitivity Analysis

In order to assess the impact of uncertainty of model inputs on total payer costs, a deterministic sensitivity analysis was conducted on model parameters where clinical inputs were varied within their 95% confidence intervals, while all other inputs were varied by ±20%.

Results

Budget Impact Analysis

The model was used to estimate the annual budgetary impact of using a single-dose of oritavancin for a hypothetical U.S. payer with 1,000,000 members. In this patient population, it was estimated that there would be approximately 14,285 ABSSSI patients treated with MRSA-active IV antibiotics; these cases were thus considered in the model.31

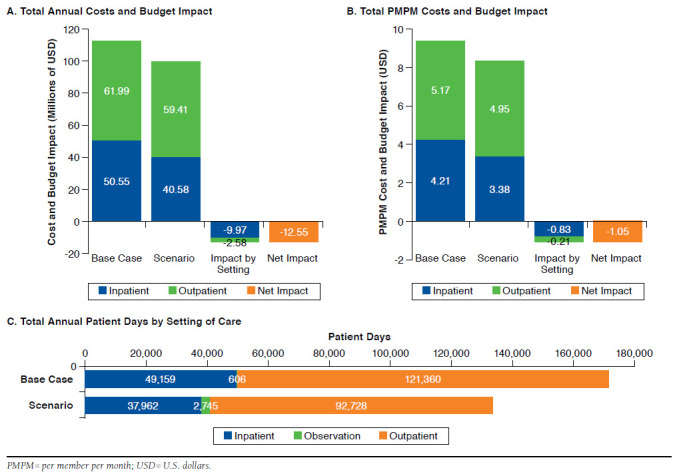

Outpatient Use Scenario

Treating 26% of moderate-to-severe ABSSSI patients with oritavancin in a predominately outpatient setting led to an expected decrease in the payer's annual budget from $112.5 million ($7,878 per patient) in the base case to $100.0 million ($7,000 per patient) in the scenario, resulting in an overall net savings of $12.5 million ($878 per patient) or 11.2% (Figure 2A). Savings were driven by cost reductions in the inpatient setting of 19.7% from $50.6 million in the base case to $40.6 million through higher use of the outpatient setting with oritavancin treatment. Although the oritavancin scenario led to greater proportions of patients treated in the outpatient setting, outpatient costs were still reduced by 4.2%, from $62.0 million in the base case to $59.4 million (Figure 2A), a result of the lower administrative burden of delivering a once-only treatment. The estimated per member per month (PMPM) costs followed a similar pattern, with a total savings of $1.05 PMPM (Figure 2B). Resource use in terms of patient days was reduced for inpatient stays and outpatient treatment days (49,159 days to 37,962 days and 121,360 days to 92,728 days, respectively). Observational days were increased from 606 days in the base case to 2,745 days in the scenario (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Budget Impact Analysis Results for a U.S. Payer with 1,000,000 Members (Outpatient Use Scenario)

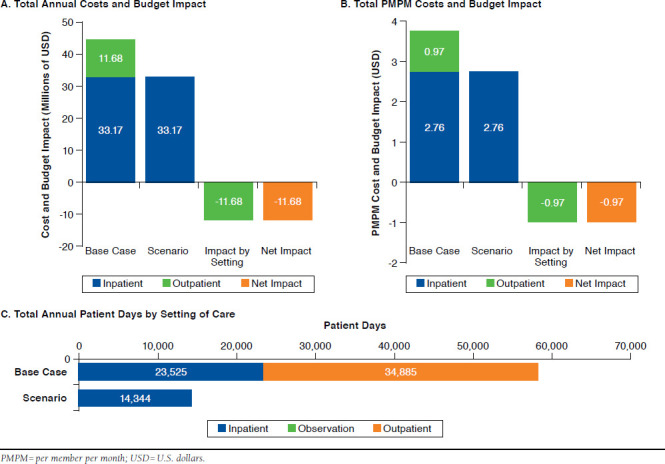

Inpatient Use Scenario

In the second scenario, the subgroup of about 5,738 van-comycin patients admitted to the hospital for 4.1 days and discharged to OPAT for the remaining 6.1 days of therapy was compared with treatment with oritavancin, assuming inpatient admission for 2.5 days followed by discharge to home. In this scenario, inpatient costs remained the same because of the DRG reimbursement mechanism, while outpatient treatment costs of $11.7 million were eliminated. Total costs decreased by 26.0%, from $44.9 million ($7,816 per patient) to $33.2 million ($5,781 per patient; Figure 3A). Vancomycin patients incurred outpatient costs of $0.97 PMPM (Figure 3B), while these costs were eliminated with use of oritavancin. As illustrated in Figure 3C, use of oritavancin reduced the total number of patient days in the inpatient setting (23,525 days to 14,344 days per patient) and outpatient setting (34,885 days to 0 days per patient, respectively).

FIGURE 3.

Budget impact Analysis Results for a US Payer with 1,000,000 Members (inpatient Use Scenario)

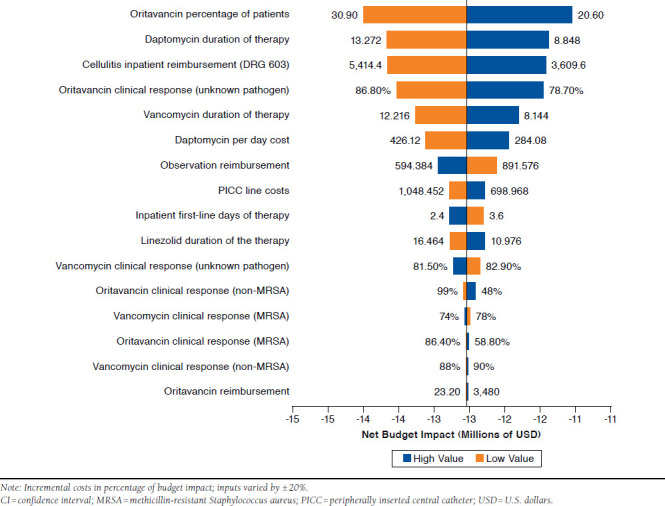

Sensitivity Analysis

The deterministic sensitivity analysis of the cost impact of introducing oritavancin found that the model was most sensitive to 7 key parameters, which had a greater than 1% impact on results. The percentage of patients receiving oritavancin had the greatest impact, with a higher percentage of oritavancin patients leading to greater potential cost savings. Duration of therapy for daptomycin and vancomycin influenced results, with fewer days of therapy reducing the potential cost savings of oritavancin. Payment rates for DRG 603 and daptomycin also impacted results with higher payments rates favoring oritavancin, while higher payment rates for observation status reduced the magnitude of cost savings.

The oritavancin response rate for unknown pathogens had a small influence on results, with lower response rates reducing total cost savings. Importantly, none of these variables impacted results sufficiently to eliminate the cost savings from oritavancin. Figure 4 includes the results from the deterministic sensitivity analysis of the 16 most important parameters.

FIGURE 4.

Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis of 16 Key Model Parameters: impact with 95% Cis for Clinical inputs and ±20% for Other inputs

Discussion

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, ABSSSI is among the top 10 leading reasons for an ED visit and is a significant burden on the U.S. health care system, with total hospitalization costs of ABSSSI estimated to be greater than $6 billion per year.7,32 Additional costs accrue to payers because of continued outpatient treatment, as well as costs associated with treatment failure and rehospitalization, which are frequently a result of nonadherence to outpatient treatments.

The purpose of this analysis was to estimate the impact on a U.S. payer's budget of introducing single-dose oritavancin into the care pathway for ABSSSI patients with suspected MRSA involvement who receive IV antibiotics. In addition, costs by setting of care and treatment strategy were analyzed to illustrate where savings can be achieved. Previous research has highlighted that Eron class II and III patients, which represent 26% of the ABSSSI population, are considered candidates for OPAT therapy. 2 In practice, however, many of these patients are admitted because of adherence concerns with outpatient treatment. This model demonstrated that the higher drug acquisition cost of oritavancin, compared with vancomycin, was offset in the inpatient and outpatient settings by reducing the hospitalization rate, lowering the need for repeated daily infusions, and eliminating the need for an indwelling IV catheter.

In the outpatient use scenario, where oritavancin was used in 26% of patients, a payer with 1,000,000 covered lives could expect to save 11.2% on the annual costs of treating moderate-to-severe ABSSSI patients. The greatest drivers of cost savings were avoided hospitalizations and elimination of continued outpatient treatment associated with multiday IV antibiotic therapy.

In the inpatient scenario, the common treatment pathway of admitting patients on vancomycin for initial treatment and discharging them to the OPAT clinic was highlighted. Here, the payer could expect to pay for admission and additionally pay for activities associated with twice-daily vancomycin OPAT infusions following discharge. Despite the low cost of generic vancomycin, use of oritavancin in these patients may save payers 26.0% through avoidance of costs associated with postdischarge OPAT.

Other analyses have presented the U.S. payer perspective on treatment of MRSA-related ABSSSI and report costs per patient in the range of $7,500-$23,000, depending on the drug.33-35 These findings are similar to the results produced by this model, which were in the range of $5,781-$7,878 per patient. While the individual published results were dependent on the design of the studies, all found total costs of vancomycin to be quite high, despite low drug acquisition costs relative to comparators. Revankar et al. (2014) found a comparable total cost of vancomycin ($8,671) with this analysis when considering a blended inpatient/outpatient treatment setting, while Stephens et al. (2013) found vancomycin costs to be even higher ($11,096) and noted that outpatient costs for vancomycin were higher than comparators.17,35 Bounthavong et al. (2011) similarly found that total costs were highest for vancomycin ($23,671), as compared with linezolid ($18,057) and daptomycin ($20,698), despite its substantially lower per day cost.34 Khatchatryan et al. (2013) demonstrated that treatment costs of IV administered antibiotics were in the range of $3,701-$15,977 per patient, with costs increasing with longer hospital LOS, indicating that significant costs could be realized from shifting more care to the outpatient setting.36

This study adds to the depth of knowledge on the economic impact of IV treatment for ABSSSI. A key strength of this model is the consideration of total costs across all settings of care from the ED and observation through admission and discharge to OPAT or home. Aside from Khatchatryan et al., who included ED costs as part of IV complications, no other economic models were identified that incorporated the cost of the ED and observation.36 Additionally, this model may provide a more accurate estimate for payer budget impact by incorporating a national prescribing pattern for 4 common first-line comparators and 12 second-line options as opposed to most models, which incorporated 1 or 2 first-line comparators and generalized costs for second-line therapy.

Limitations

A number of simplifying assumptions were made in the development of the model that may have implications on the results. An assumption was made regarding how a single-dose antibiotic would be implemented in clinical practice. It was assumed that oritavancin would be used mostly in the outpatient setting, and that when used in the inpatient setting, it would result in a shorter LOS. As the second scenario demonstrated, even when oritavancin was used entirely in the inpatient setting, the avoidance of additional outpatient treatment through its single dosing led to cost savings for the payer.

Several simplifying assumptions were made regarding costs. Cost inputs were taken from publicly available Medicare data, which will not reflect costs for all payers in the United States. Payers whose payments rates are higher than those used in this analysis will likely realize a greater savings through incorporation of oritavancin. Indirect costs, such as employees returning to work sooner or elimination of transportation costs for daily OPAT, were not captured in the model, so additional potential value of single-dose therapy was not quantified. Direct costs of providing gram-negative antibiotic coverage, radiologic studies, or use of isolation units to prevent transmission of infections were not included, since these costs are assumed to be consistent across all patients. Excluding these items effectively reduces the estimated total costs by the model equally across both arms but would not affect the magnitude of cost impact.

The assumption that treatment failures do not occur in second-line treatments may have underestimated the budget for all treatment options, but its impact was believed to be negligible. Given response rates in the 80%-90% range for all treatments, less than 4% of patients will require a third or later line of therapy; this is also consistent with other published models in infectious disease. Additionally, response rates, days of therapy, and LOS were assumed identical for first-line and second-line treatments. It is likely, however, that patients requiring second-line treatment are more difficult to treat, so total costs may be underestimated. Again, this would impact both scenarios equally.

Similar time to assessment of clinical response was assumed across all treatments and settings. If it takes longer to assess response, patients may incur more costs for an ineffective treatment. However, in vitro studies of oritavancin demonstrate 99.9% bactericidal activity within 3 hours of administration, indicating it is reasonable to assume treatment response could be assessed by day 3.37 Also, because of limited data availability, it was assumed that the outpatient pattern of switching was similar to the inpatient setting. Use of more expensive second-line therapies than what was modeled here will increase the total costs.

The simplifying assumption was made that all patients requiring multiday IV antibiotic administration received a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line. In practice, other options exist; however, sensitivity analysis indicated that the net impact of this assumption is negligible (< 2% impact on model results).

For simplicity in comparison, the IV antibiotic dalbavancin was not included in this analysis. While dalbavancin, as a twice-only dose therapy with comparable efficacy, may similarly facilitate treatment in the outpatient setting and thus will be cost saving compared with the standard of care, its higher acquisition cost relative to oritavancin and need for a second dose on day 8 make it a higher cost treatment than oritavancin.

Conclusions

This U.S. payer budget impact analysis indicated that use of oritavancin in moderate-to-severe ABSSSI patients receiving IV therapy with empiric MRSA coverage resulted in cost savings by reducing total days of patient care and through avoidance of hospitalizations. Outpatient administration costs may be reduced beyond the already lower costs of treating patients with OPAT by further eliminating the need for multiday IV drug administration. Adoption of oritavancin, a single-dose antibiotic, in the treatment of ABSSSI has the potential to eliminate nonadherence to antibiotic therapy, shorten or avoid hospitalization, and reduce overall costs to payers associated with the management of ABSSSI patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Kevin Xiang for his support in analysis of the Premier Research Database.

References

- 1.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Overview of the National Emergency Department Sample. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. January 2016. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp. Accessed April 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sulham K, LaPensee K, Fan W, Lodise TP.. Severity and costs of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections by treatment setting: an application of the Eron classification to a real-world database. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A282 [Abstract PIN99]. Available at: http://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015%2814%2901693-3/pdf. Accessed April 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hersh AL, Chambers HF, Maselli JH, Gonzales R.. National trends in ambulatory visits and antibiotic prescribing for skin and soft-tissue infections. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1585-91. Available at: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=414398. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiNubile MJ, Lipsky BA.. Complicated infections of skin and skin structures: when the infection is more than deep. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53(Suppl 2):ii37-50. Available at: http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/con-tent/53/suppl_2/ii37.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ki V, Rotstein C.. Bacterial skin and soft tissue infections in adults: a review of their epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and site of care. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2008;19(2):173-84. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2605859/pdf/jidmm19173.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moran GM, Krishnadasan, A, Gorwitz, RJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):666-74. Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMoa055356. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaPensee K, Fan W.. Economic burden of hospitalization with antibiotic treatment for ABSSSI in the US: an analysis of the Premier hospital database. Poster presented at: ISPOR 17th Annual International Meeting; June 2-6, 2012; Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.ispor.org/research_pdfs/40/pdffiles/PIN22.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen HH. Hospitalist to home: outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy at an academic center. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(Suppl 2):S220-23. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/51/Supplement_2/S220.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tice A. Oritavancin: a new opportunity for outpatient therapy of serious infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 3):S239-43. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjoumals.org/content/54/suppl_3/S239.fuU.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tice A, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, et al. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1651-72. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/38/12/1651.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng Z, Wright B, Mor V.. Sharp rise in Medicare enrollees being held in hospitals for observation raises concerns about causes and consequences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(6):1251-59. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3773225/pdf/nihms505748.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheehy AM, Caponi B, Gangireddy S, et al. Observation and inpatient status: clinical impact of the 2-midnight rule. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):203-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volz KA, Canham L, Kaplan E, Sanchez LD, Shapiro NI, Grossman SA.. Identifying patients with cellulitis who are likely to require inpatient admission after a stay in an ED observation unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(2):360-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Disease Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285-92. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/52/3/285.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CUBICIN (daptomycin for injection) for intravenous use. Merck & Co. Revised November 2015. Available at: https://www.merck.com/product/usa/pi_circulars/c/cubicin/cubicin_pi.pdf. Accessed April 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ZYVOX (linezolid) injection, tablets and oral suspension. Pfizer. January 2014. Revised July 2015. Available at: http://labeling.pfizer.com/showlabel-ing.aspx?id=649. Accessed April 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revankar N, Ward AJ, Pelligra CG, Kongnakorn T, Fan W, LaPensee KT.. Modeling economic implications of alternative treatment strategies for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections. J Med Econ. 2014;17(10):730-40. Available at: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdf/10.3111/13696998.2014.941065. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belley A, McKay GA, Arhin FF, et al. Oritavancin disrupts membrane integrity of Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococci to effect rapid bacterial killing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(12):5369-71. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2981232/pdf/0760-10.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhanel GG, Schweizer F, Karlowsky JA.. Oritavancin: mechanism of action. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(Suppl 3):S214-19. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/54/suppl_3/S214.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corey GR, Kabler H, Mehra P, et al. Single-dose oritavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2180-90. Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1310422. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corey GR, Good S, Jiang H, et al. Single-dose oritavancin versus 7-10 days of vancomycin in the treatment of gram-positive acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: the SOLO II noninferiority study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(2):254-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ORBACTIV (oritavancin) for injection, for intravenous use. The Medicines Company. 2014. Revised January 2016. Available at: http://www.orbactiv.com/pdfs/orbactiv-prescribing-information.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry. Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: developing drugs for treatment. October 2013. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/…/Guidances/ucm071185.pdf. Accessed April 9 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eron LJ, Lipsky BA, Low DE, Nathwani D, et al. Managing skin and soft tissue infections: expert panel recommendations on key decision points. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52(Suppl 1):i3-17. Available at: http://jac.oxford-journals.org/content/52/suppl_1/i3.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Premier. Premier Research Database. 2012. Charlotte, NC. Available at: https://www.premierinc.com/transforming-healthcare/healthcare-perfor-mance-improvement/premier-research-services/. Accessed April 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan W, Iorga S, Zarotsky V, et al. Care pathway and health care cost for acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection subjects with antibiotic treatment in the US: analysis of a real world database. Value Care. 2013;16(3):A94. [Abstract PIN81]. Available at: http://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015%2813%2900510-X/pdf. Accessed April 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thom H, Thompson J, Scott D, et al. Comparative efficacy of antibiotics for the treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI): a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(8):1539-51. Available at: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdfplus/10.1185/03007995.2015.1058248. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. FY 2014 IPPS Final Rule. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY-2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY-2014-IPPS-Final-Rule-CMS-1599-F-Tables.html. Accessed April 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). National and regional estimates on hospital use for all patients from the HCUP National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Rockville, MD. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp7Id=A52E8CB81DF5D9C1&Form=SelLAY&JS=Y&Action=%3E%3ENext%3E%3E&_LAY=Researcher. Accessed April 12, 2016.. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford M, Church J, eds.. CPI detailed report data for July 2014. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpid1407.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(9):1516-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2010 emergency department summary tables. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergen-cy/2010_ed_web_tables.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bounthavong M, Hsu DI, Okamoto MP.. Cost-effectiveness analysis of linezolid vs. vancomycin in treating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft tissue infections using a decision analytic model. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):376-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bounthavong M, Zargarzadeh A, Hsu DI, Vanness DJ.. Cost-effectiveness analysis of linezolid, daptomycin, and vancomycin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: complicated skin and skin structure infection using Bayesian methods for evidence synthesis. Value Health. 2011;14(5):631-39. Available at: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1098301511001094/1-s2.0-S1098301511001094-main.pdf?_tid=df4d6da2-53ac-11e4-9e31-00000aab0f6c&acdnat=1413296447_df7798a901b09b223184cc25862e52f4. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephens JM, Gao X, Patel DA, Verheggen BG, Shelbaya A, Haider S.. Economic burden of inpatient and outpatient antibiotic treatment for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus complicated skin and soft-tissue infections: a comparison of linezolid, vancomycin, and daptomycin. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:447-57. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3782516/pdf/ceor-5-447.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khachatryan A, Ektare V, Xue M, Dunne M, Johnson KE, Stephens JM.. Reducing total healthcare costs by shifting to outpatient settings of care for the management of gram+ acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI). Value Health. 2013;16(3):A203 [Abstract PHS 100]. Available at: http://www.valueinhealthjournal.com/article/S1098-3015%2813%2901096-6/fulltext#s1960. Accessed April 12, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Cock E, Sorensen S, Levrat F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of linezolid versus vancomycin for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and soft-tissue infections in France. Med Mal Infect. 2009;39(5):330-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens DL, Smith LG, Bruss JB, et al. Randomized comparison of linezolid (PNU-100766) versus oxacillin-dicloxacillin for treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(12):3408-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen HH. Hospitalist to home: outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy at an academic center. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(Suppl 2):S220-23. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/51/Supplement_2/S220.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jauregui LE, Babazadeh S, Seltzer E, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of once-weekly dalbavancin versus twice-daily linezolid therapy for the treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1407-15. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/41/10/1407.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arbeit RD, Maki D, Tally FP, et al. The safety and efficacy of daptomycin for the treatment of complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Clin Inject Dis. 2004;38(12):1673-81. Available at: http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/38/12/1673.full.pdf+html. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunbar LM, Milata J, McClure T, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of oritavancin front-loaded dosing regimens to daily dosing: an analysis of the SIMPLIFI trial. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(7):3476-84. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3122413/pdf/zac3476.pdf. Accessed April 9, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Medical Association. CodeManager. Available at: https://ocm.ama-assn.org/OCM/CPTRelativeValueSearch.do. Accessed April 9, 2016. [Google Scholar]