Abstract

BACKGROUND:

As the United States health care system shifts from traditional volume-based payments to value-based payments, outcomes-based contracts (OBCs) are gaining popularity among payers and manufacturers as a mechanism for the shift toward value. Under this model, stakeholders hope to align drug payment and value to real-world performance metrics (e.g., biomarkers and health care resource utilization).

OBJECTIVE:

To understand the experiences, perceptions, and needs of payers and manufacturers related to OBCs.

METHODS:

The Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) and Xcenda conducted an online survey with AMCP payer and manufacturer members. Participants were asked a series of questions regarding their use of OBCs, barriers to implementation, and elements required in establishing successful OBCs. The importance and urgency of specific impediments to successful OBC implementation were also assessed.

RESULTS:

The survey was fielded May 12, 2017, to June 7, 2017, yielding 65 responses (35 payers/30 manufacturers). While a minority of payers/manufacturers had at least 1 OBC in place (20%/33%), a majority had interest in future OBC use (71%/63%). Among those with at least 1 OBC in place, 86%/80% of payers/manufacturers had renewed at least 1 OBC in the past 5 years. All payers and 60% of manufacturers with OBCs included compliance measures. Improvement in clinical outcomes was also common (71%/70%) (e.g., reaching set laboratory values goals), and 71%/60% included avoidance of unnecessary medical resource use (e.g., hospitalization and emergency department visit). The barrier most frequently identified by payers in implementing OBCs was evidence that OBCs reduced pharmacy spending (60%), while manufacturers identified the inability to obtain accurate data/outcome measures (73%) as a major limiting factor. Payers/manufacturers endorsed the use of easily measurable outcomes (91%/100%) as most important in establishing successful OBCs. Manufacturers, and to a lesser extent payers, indicated that regulations and legal issues need to be addressed to make progress in OBC implementation (e.g., safe harbor for preapproval health care economic information [77%/46%] and exemption of OBCs for best-price requirements [83%/51%]). The only exception was the clarification of regulations for discussing information outside of an FDA-approved label, in which both manufacturers and payers indicated a very strong need (100%) to be addressed.

CONCLUSIONS:

Surveyed AMCP members are interested in OBCs and recognize their alignment to societal health goals and health care affordability, although actual use of these contracts has been somewhat limited to date. Results from this survey indicate that there is potential for OBC use to increase as barriers and limitations are addressed.

What is already known about this subject

Payers focus more on managing costs while improving care coordination, quality performance, and patient outcomes.

An outcomes-based contract (OBC) ties manufacturer compensation to the actual value or performance of outcomes in the payer’s population.

What this study adds

This investigative study used survey methodology to determine the current experiences and perceptions of OBCs by payers and manufacturers who are members of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy, which allowed for comparisons between groups.

Payer and manufacturer respondents indicated that the inability to obtain accurate data or outcomes measures, inability to discuss information outside the FDA-approved label, privacy of patient data/HIPAA compliance, potential health care compliance risks, and costs or other barriers to implementing data collection technology as limiting factors associated with OBCs.

Survey participants reported that clarification of industry regulations, availability of common information technology structures, best-practice guidelines, and the creation of safe harbors for payers and manufacturers to proactively share information on emerging therapies must be addressed in order to support the implementation of OBCs.

The U.S. health care system is currently undergoing an evolution from a fee-for-service payment system to a modernized system rewarding quality, improved patient outcomes, and value. As part of that evolution, payers and manufacturers are exploring contemporary models to navigate continued innovation in health technologies and their corresponding costs. In recent years, one contemporary model that has emerged is a contracting strategy that does not base payment on volume of medications sold but instead ties payment to the achievement of specific goals in a predetermined patient population and rewards good patient outcomes.

Thus far, approximately 20 of these contemporary contracting strategies, referred to as outcomes-based contracts (OBCs), have been implemented in the United States.1 Given the potential for OBCs to reduce health care costs while improving patient outcomes, there is interest in expanding the number of OBCs that are implemented in the future. However, payers and manufacturers have expressed that entering into OBCs is a cumbersome process with several challenges and barriers.

To identify, quantify, and better understand the challenges and barriers payers and manufacturers experience when attempting to enter into an OBC, the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP) membership was surveyed to gain insight regarding their experiences, perceptions, and readiness to implement OBCs. The results of the survey served as a precursor for a Partnership Forum that AMCP convened in June 2017 with a diverse group of national stakeholders to develop solutions and recommendations for addressing the identified challenges and barriers to help increase the number of executed OBCs and further support the evolution toward payment for value.2 OBCs were assessed in the survey, as opposed to value-based contracts (VBCs), because VBCs can be synonymous with market share and contracting, and the focus of the AMCP Partnership Forum was on value as defined by outcomes and quality.

Methods

Participants, Procedure, and Survey

An online survey was used to obtain information regarding OBCs from AMCP members. AMCP members operate in various health care-related occupations, including pharmacy and medical directors, executive administrators, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and managed care experts within the private and public payer spaces. Participants were recruited by means of a recruitment email sent to the nonstudent AMCP member directory (approximately 5,000 members). The survey was fielded from May 12, 2017, to June 7, 2017.

Survey concepts were developed after initial discussions between AMCP and key AMCP stakeholders, such as payers and manufacturers, based on challenges experienced in today’s marketplace. The survey was intended to validate anecdotal issues and was developed for the purpose of guiding the AMCP Partnership Forum on value-based contracting.2

The introduction to the survey defined OBCs as those intended to align pricing with a medicine’s real-world performance on metrics such as biomarkers, health care resource utilization, and clinical outcomes. The survey consisted of 22 questions and was approximately 15 to 20 minutes in length. Skip patterns were used to include applicable questions for payers and manufacturers. When applicable, item responses were randomized. Initial screening questions captured survey respondent and organizational characteristics, including their current role within the health care industry and organization type such as managed care organization/health plan, health system or hospital, and accountable care organization. The remainder of the survey contained items assessing their organization’s current use of OBCs, barriers faced in implementing OBCs, organizational resources in place to facilitate OBC implementation, and rating the importance of elements in establishing successful OBCs. (Survey is available from authors upon request.) The survey was single-blinded and participation was voluntary. Survey participants were not incentivized or reimbursed for their survey completion.

Results

A total of 96 respondents completed the survey. The survey sample for this analysis comprised 65 respondents: 35 payers and 30 manufacturers. Other survey respondents were excluded from the survey respondent data analysis because they were not payers or manufacturers (e.g., academics, other parties interested in OBCs). Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Respondent Characteristics

| Payer Respondent Profiles | |

|---|---|

| Current organizational status, n (%) | |

| Currently with an organization providing managed care to covered lives | 32 (91) |

| Other | 2 (6) |

| Currently with a health system/hospital | 1 (3) |

| Books of business represented, n (%) | |

| Medicare Advantage | 28 (80) |

| Commercial | 27 (77) |

| Managed Medicaid | 24 (69) |

| Health insurance exchange | 22 (63) |

| Medicare Part D/prescription drug plan | 19 (54) |

| 340B | 7 (20) |

| Other | 3 (9) |

| Current primary job function, n (%) | |

| Pharmacy director | 18 (51) |

| Medical director | 5 (14) |

| Other: please specify | 5 (14) |

| Contracting director | 3 (9) |

| Clinical pharmacist | 2 (6) |

| Executive administrator (e.g., CEO, CFO) or administrative director | 2 (6) |

| Plan coverage, n (%) | |

| Regional | 20 (57) |

| National | 15 (43) |

| Covered lives (n) | |

| Mean (SD) | 7,646,070 (19,378,669) |

| Median | 1,200,000 |

| Manufacturer Respondent Profiles | |

| Current role within the health care industry, n (%) | |

| Managed markets or market access | 9 (30) |

| Health economics and outcomes research | 6 (20) |

| Consultant | 4 (13) |

| Medical affairs | 4 (13) |

| Field account manager, national | 3 (10) |

| Field account manager, regional | 2 (7) |

| Contracting/industry relations | 1 (3) |

| Legal affairs | 1 (3) |

Note: Participant characteristics are a percentage of the total sample. CEO = chief executive office; CFO = chief financial officer; SD = standard deviation.

Perceptions of OBCs

Participants answered questions regarding their organization’s current and planned use of OBCs. Payers and manufacturers indicated whether or not they currently had at least 1 OBC in place (20% and 33%, respectively) or showed an interest in using OBCs (71% and 63%, respectively). Among respondents currently implementing OBCs, payers had an average of 5.1 OBCs executed or pending within the past 5 years, while manufacturers had an average of 3.5. For those who executed at least 1 OBC, the majority of payers (86%) and manufacturers (80%) had renewed at least 1 of their OBCs in the past 5 years.

Participants were also questioned regarding the specific measures that were included in their organizations’ current OBCs. All payers and 60% of manufacturers with OBCs in place included compliance measures (e.g., medication possession ratio and length of therapy) in the contract. Improvement in clinical outcomes (71% and 70%, respectively) and avoidance of resource use (e.g., hospitalizations and emergency department visits; 71% and 60%, respectively) were often included in payer and manufacturer OBCs, while fewer (14% and 10%, respectively) included the experience of adverse events within their OBCs.

Barriers and Limitations in Implementing OBCs

To better understand the barriers payers faced in the implementation of OBCs, payers were provided with 12 different potential barriers and asked to select all that applied. The most frequently identified barriers in implementing OBCs noted by payers were the perception of limited or no evidence that OBCs affect the following: reduce pharmacy spending (60%), inability to obtain accurate/credible data to measure outcomes (49%), cost barriers to implementing data collection technology (43%), ability to negotiate acceptable terms (43%), lack of experience with this type of contracting (43%), just another way to extract rebates (23%), regulatory barriers that prevent pharmaceutical companies from disclosing information needed to enter into outcomes-based agreements (23%), privacy of patient data/Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliance (20%), pharmaceutical companies’ inability to discuss information that is outside of approved labeling by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA; 17%), compliance risks other than privacy (14%), and unwillingness to enter into agreements (14%).

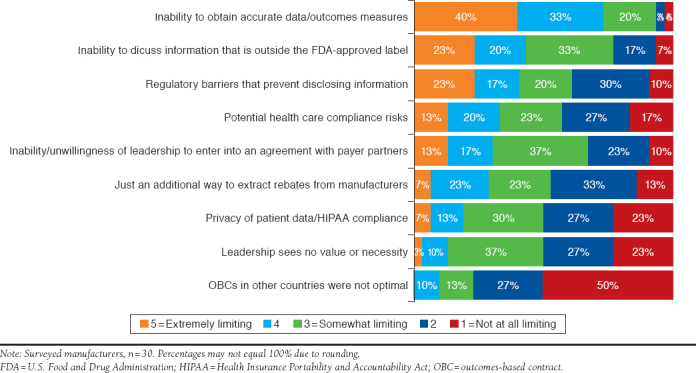

Manufacturers were asked to rate the extent to which various barriers limit the implementation of OBCs on a scale of 1 to 5, with scores of 4 and 5 considered the most limiting. Similar to payers, manufacturers identified the inability to obtain accurate data/outcome measures (73%) as a major limiting factor for implementation of OBCs. The inability to discuss information outside of the FDA-approved labeling (43%) and regulatory barriers (40%) were also major limiting factors associated with OBCs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Potential Limiting Factors for Manufacturer OBCs

Important Elements in the Successful Implementation of OBCs

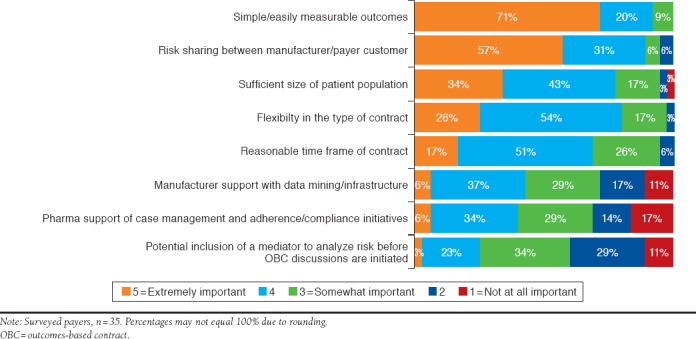

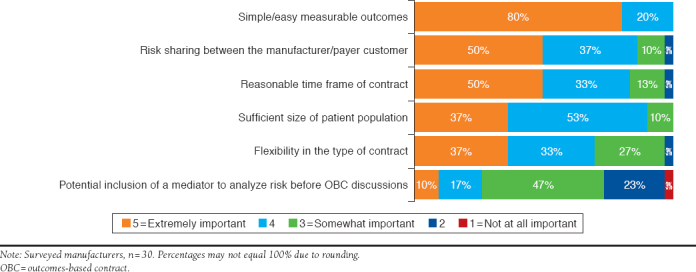

Payers and manufacturers rated the importance of 8 potential elements necessary in establishing successful OBCs on a scale of 1 to 5, with scores of 4 and 5 being most important. The most critical element in establishing successful OBCs for both payers and manufacturers was simple/easily measured outcomes (71% and 80%, respectively). Other critical elements included risk sharing between payers and manufacturers and their customers (57% and 50%, respectively), reasonable time frames for contracts (17% and 50%, respectively), sufficient patient populations (34% and 37%, respectively), and contract flexibility (26% and 37%, respectively; Figure 2 and Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Critical Elements in Successful Payer OBCs

FIGURE 3.

Critical Elements in Successful Manufacturer OBCs

Urgent and Impactful Elements of OBCs

Respondents completed 7 items describing potential elements that may facilitate OBCs and were asked to indicate both the impact and urgency levels of each element on a scale of 1 (no impact/not urgent) to 5 (extremely impactful/extremely urgent).

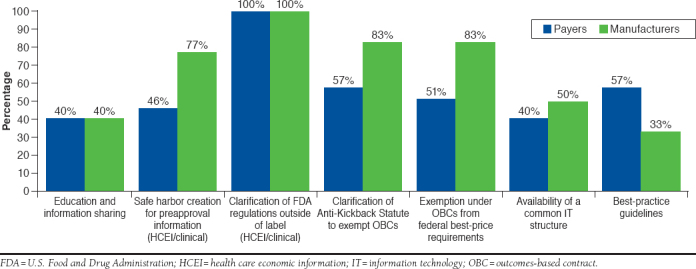

Among the most impactful measures (scores of 4 or 5), both payers and manufacturers identified clarification of FDA regulations outside of product labeling (100% for both), clarification of the Anti-Kickback Statute (57% and 83%, respectively), and exemptions under OBCs from federal best-price requirements as highly impactful (51% and 58%, respectively). Among payers, best-practice guidelines were impactful (57%), while among manufacturers, creation of a safe harbor to exchange clinical and health care economic information (HCEI) prior to a product’s approval (77%) was impactful (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Impactful Elements in the Facilitation of OBCs

Clarification of the Anti-Kickback Statute had a high urgency rating among approximately half (46%) of payers. However, among manufacturers, clarification of the Anti-Kickback Statute (67%) was considered by a majority to be urgent. Other urgent measures identified by payers and/or manufacturers included exemption under OBCs from federal best-price requirements (40% and 57%, respectively), clarification of FDA regulations for communicating information outside of label (31% and 67%, respectively), and safe harbor creation for preapproval information, including health care economic and clinical data (31% and 67%, respectively). Best-practices guidelines were deemed urgent by 40% of payers, but manufacturers seemed to place less urgency on having guidelines in place (27%). For payers and manufacturers, education and information sharing (26% and 37%, respectively) and availability of a common information technology structure (17% and 33%, respectively) were the least urgent of all elements. Overall, the need to address laws and regulations is potentially more critical for manufacturers than for payers; however, significance testing was not conducted.

Discussion

Future qualitative and/or quantitative research should address topics such as satisfaction and success of implemented OBCs from payer and manufacturer perspectives. Implications for OBCs such as their impact on formulary decision making and everyday clinical practice should be addressed as well. Finally, OBCs are often based on clinical trial data, and how these outcomes translate into real-world outcomes, such as efficacy and safety outcomes, is worth exploring in future assessments of OBCs.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, there was a low response rate and a small sample size. While the survey was sent to approximately 5,000 AMCP members, only 65 responses were received, and therefore the results may not reflect the perceptions or experiences of the larger AMCP membership with OBCs. There is also potential for a biased sample as AMCP members with an interest in the topic completed the survey. In addition, the small sample size limited the ability to conduct various within-group comparisons, such as looking at whether identified challenges and barriers differed among groups that did or did not have at least 1 OBC in place or differences based on payer type (commercial, Medicare, or Medicaid). Despite these limitations, findings are generally similar to a 2017 survey conducted with manufacturers regarding legal/regulatory and operational barriers to VBCs, providing greater confidence in our manufacturer study results.

Second, the survey was designed with predetermined options for selection and did not provide an opportunity for respondents to select “other” or input a response that was not listed. Therefore, there may be additional challenges and barriers that respondents experienced that were not identified. Open-ended response options were generally not included in the survey due to time constraints related to when this survey was fielded and timing of data needs for the AMCP Partnership Forum. In addition, questions did not include a “none of the above” option and, therefore, respondents may have felt forced to select at least 1 challenge or barrier, even if they felt that they did not experience any in implementing an OBC.

Finally, the survey used the term “OBCs.” The terminology used may have limited response or influenced the results, since there are several terms that are used to describe these contemporary contracting designs. The term “VBC” is a broader umbrella term that encompasses OBCs and other innovative contracting strategies that may not be tied to a specific predetermined patient outcome. Therefore, the use of “OBC” versus “VBC” may have deterred or confused some respondents who were not aware of the nuances between the 2 terms. However, the survey item regarding which measures are included in OBCs did include response options such as measures of compliance, avoidance of resource use, improvement in clinical outcomes, and experience of adverse events.

Conclusions

OBCs have the potential to slow the growth of health care spending in the United States while improving patient and population outcomes, but there are several challenges and barriers that impede the ability of payers and manufacturers to enter into these agreements more readily. To increase the utilization of OBCs, strategies to address these challenges and barriers must be developed and implemented. In addition, best practices in evaluating, implementing, and monitoring OBCs should be identified to encourage additional payers and manufacturers to enter into these agreements.

REFERENCES

- 1.Network for Excellence in Health Innovation . Rewarding results: moving forward on value-based contracting for biopharmaceuticals. March 23, 2017. Available at: http://www.nehi.net/publications/76-rewarding-results-moving-forward-on-value-based-contracting-for-biopharmaceuticals/view. Accessed November 24, 2017.

- 2.AMCP partnership forum: advancing value-based contracting . J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(11):1096-102. Available at: http://www.jmcp.org/doi/full/10.18553/jmcp.2017.17342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]