Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Over the past decade, oncology therapies have trended toward orally administered regimens, and there has been growing attention on evaluation of factors that affect adherence. There has not been a rigorous investigation of factors associated with adherence to intravenous (IV) and oral anticancer drugs in the setting of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC).

OBJECTIVES:

To (a) assess potential patient-specific factors related to adherence to mCRC chemotherapy regimens and (b) compare adherence with IV versus oral dosage forms.

METHODS:

A retrospective analysis was performed using the Optum Oncology Management claims database. Patients aged 18 years and older diagnosed with mCRC between July 1, 2004, and December 31, 2010, who were insured by a commercial health plan were included in the study. Adherence to IV and oral chemotherapy regimens was assessed using the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines as the standard for expected cycle/regimen duration. The most commonly prescribed chemotherapy regimens were assessed. Adherence was evaluated using the medication possession ratio (MPR), calculated as the number of days a patient was covered by their chemotherapy regimen, according to NCCN guidelines, divided by the number of days elapsed from the first to the last infusion of that regimen. For most analyses, the MPR was considered a continuous variable that could take on values between 0 and 1. In other analyses, a dichotomous categorical variable designated if the MPR was at least 0.8 versus less than 0.8. The Wilcoxon rank sum, Kruskal-Wallis, and Student’s t-test were used to detect differences in continuous measures between patients receiving oral capecitabine therapy versus IV chemotherapy. The chi square test (X2 test) or Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences in the dichotomous MPR variable. Generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used for regimen-level analyses to account for correlated responses within individuals.

RESULTS:

A total of 6,780 patients were included in the analysis, virtually all (98%) with commercial insurance coverage and the remaining (2%) with Medicare Advantage. Patients with mCRC received 17,095 regimens of chemotherapy, including 2,252 regimens of oral capecitabine. Of the 17,095 regimens, 6,780 (40%) were first-line regimens (i.e., the first time mCRC was treated for a given patient). The most common chemotherapy regimen, regardless of line of therapy, was FOLFOX (2,991 regimens, 17.5% of all regimens used). FOLFOX-based therapies with or without bevacizumab were the most common regimens for first- and second-line chemotherapy, while oral capecitabine treatment was the most commonly prescribed regimen for patients in third- or fourth-line therapy. Overall, medication adherence across all regimens was relatively high, with a mean MPR of 0.87 (SD = 0.17). Evaluation of the distribution of IV and oral capecitabine regimens revealed that 28% of all regimens were associated with an MPR of less than 0.8. The average MPR was clinically similar, but statistically higher for IV chemotherapy regimens (0.881) compared with oral capecitabine regimens (0.799; P < 0.0001). In the multivariable GEE model, lung or liver metastases were associated with a higher MPR, while lower Charlson Comorbidity Index and oral anticancer therapy were associated with lower MPR. Furthermore, as line of therapy increased, the difference in MPR between patients receiving oral capecitabine and IV chemotherapy increased.

CONCLUSIONS:

This analysis determined that adherence with IV chemotherapy regimens was clinically similar, but statistically higher, compared to oral capecitabine therapy. The difference in adherence rates between the 2 routes of administration increased as the line of anticancer regimen increased. These results suggest that there should be an increased focus on improving adherence rates in patients receiving oral capecitabine.

What is already known about this subject

Over the past decade, oncology therapies have trended toward orally administered regimens, and this trend is likely to continue in the future.

Oral anticancer therapies can convey numerous benefits for patients, including convenience, decreased interference with work, avoidance of catheter-related discomfort and complications, and decreased infusion clinic visits.

Nonadherence is possible in the less supervised outpatient setting where oral anticancer medications are taken.

What this study adds

Although adherence was high among patients taking both IV chemotherapy regimens and oral capecitabine, adherence was significantly lower for patients taking oral capecitabine.

There was a greater discrepancy in adherence between the 2 types of regimens as the line of anticancer regimen increased.

These results suggest that there should be an increased focus on improving adherence rates in patients receiving oral capecitabine.

Over the past decade, oncology therapies have trended toward orally administered regimens. Recent evidence suggests that up to 25% of approved agents and those in preapproval pipelines are oral anticancer agents.1 Oral anticancer therapies can convey numerous perceived benefits for patients including convenience, decreased interference with work, avoidance of catheter-related discomfort and complications, and decreased infusion clinic visits.2-6 There are, however, potential challenges with oral anticancer agents, such as novel toxicity profiles and the important role that nonadherence may play in a less supervised setting.1-3,5-7 Nonadherence is of particular clinical importance in treating cancer due to its association with higher costs, unnecessary diagnostic testing, and worse patient outcomes.6

Given the increasing usage of oral anticancer agents, there has been growing attention on evaluation of factors that affect adherence. Potential factors affecting adherence include those related to the patient, health care system, and treatment. A recent systematic review of factors associated with adherence to oral anticancer agents identified multiple patient-focused factors, including stage of cancer, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), duration of therapy, education, social support, socioeconomic status, and toxicity profile.7 It is widely assumed that adherence to intravenous (IV) chemotherapy regimens is significantly greater than adherence to oral chemotherapy regimens. However, there has not been a rigorous investigation of patient-related factors associated with IV and oral anticancer drugs in the setting of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). The objective of this study was to identify treatment patterns in patients with mCRC, identify patient-specific factors related to adherence to mCRC chemotherapy regimens, and assess for differences in adherence between IV and oral anticancer regimens.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed using the Optum Oncology Management claims database. All database records were deidentified and fully compliant with U.S. patient confidentiality requirements (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act); therefore, the study was exempt from institutional review board approval. This database contains claims-based records of all outpatient pharmacy prescription fills and outpatient procedure and diagnosis codes for commercially insured patients with breast, lung, colorectal, or prostate cancer. Patients aged 18 years and older diagnosed with mCRC between July 1, 2004, and December 31, 2012, who were insured by a commercial health plan were included in the study. If a patient had a primary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code for colorectal cancer (153.0x-153.4x, 153.6x-153.9x, 154.0x, 154.1x, and 154.8x) and any ICD-9-CM code for metastasis (196-198.99), they were considered to have mCRC. To be included, patients were required to be continuously enrolled in the Optum Oncology Management claims database for at least 6 months prior to (i.e., baseline period) and subsequent to (i.e., study period) the index date. The index date was defined as the date that the first ICD-9-CM code for metastasis was observed in patients with colorectal cancer. Patients were excluded if there was evidence of other cancers during the baseline period, as defined by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes (140.xx-239.9x, excluding the colorectal cancer codes listed previously), or if patients were not continuously enrolled for 6 months pre- and 6 months post-index date.

Chemotherapy regimens were identified 2 ways. Outpatient prescriptions for oral capecitabine, the only oral anticancer agent recommended by the NCCN for mCRC during the study time frame, were identified by the National Drug Code in the outpatient prescription claims dataset. IV chemotherapy regimens were identified using drug-specific outpatient procedure codes (J-codes).

The primary outcome variable in this study was the medication possession ratio (MPR), a measure of medication adherence. Adherence to each regimen of oral capecitabine therapy was calculated as the total days supplied for billed dispenses from the pharmacy of that regimen (obtained directly from the prescription claims) in the study period divided by the actual number of days that accrued during the regimen. The MPR calculation was adjusted to account for oral capecitabine typically being administered 2 weeks on treatment followed by a 1-week period with no therapy. The length of each regimen was determined starting on the day the first prescription was filled and lasting until the days supply was exhausted for the last prescription in that regimen. Prescriptions of oral capecitabine that occurred greater than 60 days apart were considered to be part of different regimens for these calculations. Adherence to IV chemotherapy regimens was calculated as the number of days covered by a chemotherapy regimen divided by the actual number of days that accrued during that regimen. The number of days covered for regimens was based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for colon cancer therapy. For example, these guidelines specify that FOLFIRI treatment should occur every 2 weeks. FOLFIRI is a common chemotherapy regimen composed of folinic acid (FOL), 5-fluorouracil (F), and irinotecan (IRI). Therefore, we considered 14 days to be covered, beginning on the day of infusion (obtained directly from the procedure claim) for that regimen. The length of each regimen was determined starting on the day of the first infusion of that regimen and lasting until the covered days were exhausted for the last infusion of that regimen. We considered IV administration of the same chemotherapy agent that occurred greater than 60 days apart to be different regimens for these calculations. We also conducted sensitivity analyses by adjusting this window of time between 45 and 90 days to see if study inferences were sensitive to this specification.

The MPR was considered a continuous variable that could take on values between 0 and 1. As is customary in medication adherence studies, if the calculated MPR exceeded 1, it was assigned a value of 1.8,9 For analytic purposes, a dichotomous categorical variable based on the continuous MPR variable was created, designating when the MPR is at least 0.8 versus less than 0.8.

Analyses were conducted at the regimen and patient levels and occurred in 3 stages. First, a descriptive analysis of adherence rates to oral capecitabine and the most commonly prescribed IV chemotherapy regimens was conducted. Second, a series of bivariate analyses were conducted to assess the relationship between MPR and line of chemotherapy, location of metastatic disease, age, comorbidity, and route of chemotherapy treatment. Lastly, a multivariate analysis was conducted to assess the relationship between MPR (the outcome variable) and line of chemotherapy, location of metastatic disease, age, comorbidity, and route of chemotherapy treatment when considered in the same statistical model.

The Wilcoxon rank sum, Kruskal-Wallis, and Student’s t-test were used to detect differences in continuous measures between patients receiving oral capecitabine therapy versus IV chemotherapy. The X2 or Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences in the dichotomous MPR variable. GEE models were used for regimen-level analyses to account for correlated responses within individuals.10 Two forms of GEE models were implemented. In the first form, MPR was treated as a continuous variable. For these models, a Gaussian distribution, identity link function, and autoregressive correlation structure were specified. In the second form, the dichotomous MPR variable was the outcome variable. For these analyses, a binomial distribution, logit link function, robust variance estimation, and exchangeable correlation structure were specified. Bivariate and multivariate GEE analyses were conducted for both the continuous and dichotomous MPR variables. Final model selection for multivariate models used a forward selection process, starting with the most significant variables from bivariate analyses, and included variables that achieved a significance level of P < 0.1 or lower in bivariate analyses. The final model selection process was guided by the quasilikelihood under the independence model criterion. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant in final models. Stata statistical software version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

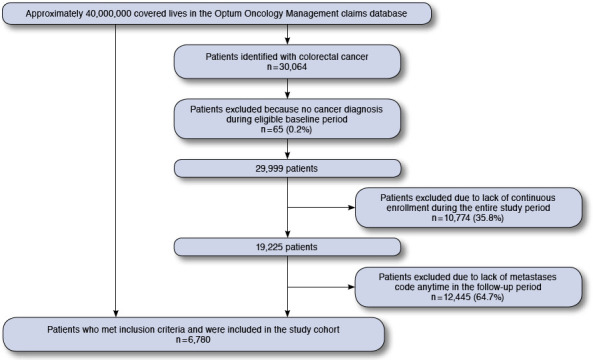

A total of 6,780 patients met inclusion criteria and were included in the study cohort, and virtually all (98%) had commercial insurance coverage from July 1, 2004, to December 31, 2012. The sample selection flow chart can be seen in Figure 1. Summary statistics and characteristics for included patients can be found in Table 1. This electronic patient health record database of mCRC patients revealed a mean age of 54 years (standard deviation [SD] = 11), with 7% of patients aged greater than 65 years. Slightly more patients were male, and all regions of the country were represented, with the northeast region notably underrepresented at 7%. The majority of patients had lung and/or liver metastases. The majority of patients received only 1 or 2 lines of chemotherapy (65%).

FIGURE 1.

Sample Selection Flow Chart

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and Summary Statistics for Included Patients

| Total number | 6,780 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | |

| Mean (SD) | 54 (11) |

| > 65 years of age, n (%) | 480 (7) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 1,903 (57) |

| Female | 1,464 (43) |

| U.S. census region, n (%) | |

| Midwest | 2,289 (26) |

| Northeast | 651 (7) |

| South | 4,738 (53) |

| West | 1,293 (14) |

| Type of metastatic disease, n (%) | |

| Lung metastases only | 622 (9) |

| Liver metastases only | 1,724 (25) |

| Lung and liver metastases | 1,514 (22) |

| Other metastatic disease | 2,920 (43) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| Mean (SD) | 9.61 (1.88) |

| Median (interquartile range) | 9 (8-10) |

| Total number of lines of chemotherapy received, n (%) | |

| 1 | 2,747 (41) |

| 2 | 1,654 (24) |

| 3 | 902 (13) |

| 4 + | 1,477 (22) |

SD = standard deviation.

Patients with mCRC received 17,095 regimens of chemotherapy, including 2,252 prescriptions of oral capecitabine. Of the 17,095 overall regimens, 6,780 (40%) were first-line regimens. The most common 10 regimens, by line of treatment, are summarized in Table 2. The most common chemotherapy regimen used in this population, regardless of line of therapy, was FOLFOX (2,991 regimens, 17.5% of all regimens used). FOLFOX is a common chemotherapy regimen composed of folinic acid (FOL), 5-fluorouracil (F), and oxaliplatin (OX). FOLFOX-based therapies with or without bevacizumab were the most common regimens for first- and second-line chemotherapy, while oral capecitabine treatment was the most commonly prescribed regimen for patients in their third or fourth line of therapy.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of the Most Common Chemotherapy Regimens, by Line of Therapy

| Chemotherapy Regimen | Number of Patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| First line (n = 6,780) | ||

| FOLFOX | 2,078 | 30.7 |

| Oral capecitabine | 1,030 | 15.2 |

| FOLFOX + bevacizumab | 870 | 12.8 |

| 5-FU monotherapy | 838 | 12.4 |

| FOLFIRI + bevacizumab | 299 | 4.4 |

| Paclitaxel + carboplatin | 175 | 2.6 |

| Oxaliplatin monotherapy | 140 | 2.1 |

| FOLFIRI | 119 | 1.8 |

| Bevacizumab monotherapy | 104 | 1.5 |

| 5-FU + bevacizumab | 85 | 1.3 |

| Second line (n = 4,033) | ||

| FOLFOX | 574 | 14.2 |

| FOLFOX + bevacizumab | 487 | 12.1 |

| Oral capecitabine | 476 | 11.8 |

| 5-FU monotherapy | 439 | 10.9 |

| FOLFIRI + bevacizumab | 383 | 9.5 |

| 5-FU + bevacizumab | 247 | 6.1 |

| Oxaliplatin monotherapy | 186 | 4.6 |

| Bevacizumab monotherapy | 162 | 4.0 |

| Oxaliplatin + bevacizumab | 123 | 3.0 |

| FOLFIRI | 118 | 2.9 |

| Third line (n = 2,379) | ||

| Oral capecitabine | 279 | 11.7 |

| FOLFIRI + bevacizumab | 268 | 11.3 |

| Bevacizumab monotherapy | 210 | 8.8 |

| FOLFOX + bevacizumab | 195 | 8.2 |

| FOLFOX | 189 | 7.9 |

| FOLFIRI | 153 | 6.4 |

| 5-FU + bevacizumab | 152 | 6.4 |

| 5-FU monotherapy | 111 | 4.7 |

| Cetuximab monotherapy | 100 | 4.2 |

| Cetuximab + irinotecan | 83 | 3.5 |

| Fourth line (n = 1,477) | ||

| Oral capecitabine | 189 | 12.8 |

| FOLFIRI + bevacizumab | 158 | 10.7 |

| Bevacizumab monotherapy | 138 | 9.3 |

| Cetuximab monotherapy | 91 | 6.2 |

| Cetuximab + irinotecan | 88 | 6.0 |

| FOLFOX + bevacizumab | 85 | 5.8 |

| FOLFIRI | 82 | 5.6 |

| 5-FU + bevacizumab | 77 | 5.2 |

| FOLFOX | 63 | 4.3 |

| 5-FU monotherapy | 59 | 4.0 |

5-FU = 5-fluorouracil; FOLFIRI = folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan; FOLFOX = folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin.

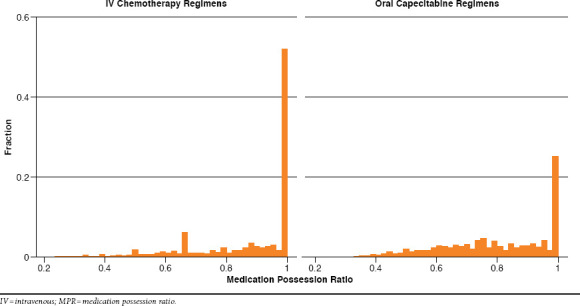

Overall, medication adherence across all regimens was relatively high, with a mean MPR of 0.87 (SD = 0.17). Evaluation of the distribution of IV chemotherapy and oral capecitabine regimens revealed that 72% of all regimens were associated with an MPR of 0.8 or greater and 90% of regimens were associated with an MPR of 0.6 or greater. The distribution of MPR across all regimens was skewed toward good adherence (i.e., MPR = 1; see Figure 2 and Table 3). The median MPR across all regimens was 0.97, and 47% of all regimens were associated with an MPR = 1. Adherence tended to be high across all lines of therapy, CCI score, age, location of metastatic disease, gender, and route of anticancer therapy. Differences in MPR that we considered to be clinically trivial were nevertheless found to be statistically significant between levels of disease severity, type of metastatic disease (continuous MPR variable only), and gender (Table 3). IV regimens were associated with a statistically higher MPR (for both the continuous and dichotomous MPR variables).

FIGURE 2.

Distributions of MPR for IV Chemotherapy and Oral Capecitabine Regimens

TABLE 3.

MPR, Overall for Patients with Metastatic Disease and by Patient and Regimen Characteristics (N = 17,095 Regimens)

| Patient and Regimen Characteristics | Number of Regimens | MPR, mean (SD) | Percentage of Regimens with MPR of ≥ 0.8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 17,095 | 0.870 (0.17) | 72 |

| Line of treatment | |||

| First line | 6,780 | 0.867 (0.17) | 72 |

| Second line | 4,033 | 0.869 (0.17) | 71 |

| Third line | 2,379 | 0.875 (0.17) | 73 |

| Fourth line and above | 3,903 | 0.874 (0.17) | 72 |

| Disease severity | |||

| CCI ≤ 9 | 10,214 | 0.873 (0.17)a | 73d |

| CCI > 9 | 6,881 | 0.867 (0.17) | 71 |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 65 years | 14,779 | 0.871 (0.17) | 72 |

| > 65 years | 2,316 | 0.867 (0.18) | 72 |

| Type of metastatic disease | |||

| Lung or liver | 11,863 | 0.861 (0.18)b | 71 |

| Other | 5,232 | 0.874 (0.17) | 73 |

| Gender | |||

| Males | 9,473 | 0.876 (0.17)c | 73c |

| Females | 7,622 | 0.863 (0.17) | 70 |

| Route of administration | |||

| Oral capecitabine | 2,252 | 0.799 (0.18)c | 52c |

| IV chemotherapy | 14,843 | 0.881 (0.17) | 75 |

Statistical significance indicated by the following:

aP = 0.023 by linear regression using GEE model to account for correlated responses within individuals.

bP = 0.004 by linear regression using GEE model.

cP < 0.0001 by linear regression using GEE model.

dP = 0.014 by logistic regression using GEE model.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; GEE = generalized estimating equations;

MPR = medication possession ratio; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 2 shows histograms of the distribution of MPR values for IV chemotherapy and oral capecitabine regimens independent of line of therapy. Approximately 50% of IV chemotherapy and 25% of oral capecitabine regimens were associated with an MPR of 1.0. Seventy-five percent of IV chemotherapy regimens were associated with an MPR of at least 0.8 compared with 52% of oral capecitabine regimens (P < 0.0001 by logistic regression in a GEE model). Ten percent of regimens of IV chemotherapy had an MPR less than 0.63, whereas the lowest 10% of regimens of oral capecitabine had an MPR of less than 0.55.

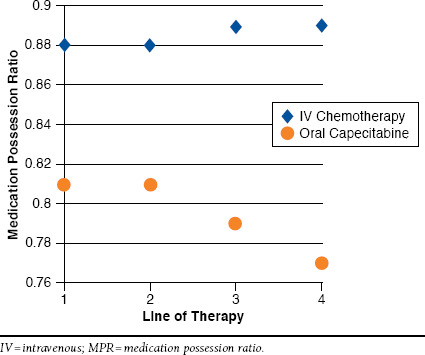

Average MPR was clinically similar but statistically higher for IV chemotherapy regimens (0.881) compared with oral capecitabine regimens (0.799; P < 0.0001). Other significant bivariate relationships: CCI score < 9 had a moderately but significantly higher MPR compared with patients whose score was 9 or greater (0.873 vs. 0.867; P = 0.023). Other modest but significant differences in MPR were detected between patients with lung or liver metastases (average MPR = 0.874) compared with patients with other metastatic involvement (0.861; P = 0.004) and between males (MPR = 0.876) and females (0.863; P < 0.0001). To inform the multivariate modeling process, we also assessed for interaction effects between the mode of treatment (IV/oral) and line of the therapy. A significant interaction effect was detected between line of therapy and treatment type. This relationship can be visualized in Figure 3. From chemotherapy lines 1-4, adherence improved marginally but not significantly for patients receiving IV therapy (see Figure 2). In comparison, medication adherence worsened significantly as the line of therapy increased for patients receiving oral capecitabine therapy (P < 0.0001 by regression using the GEE model). This interaction effect was included as a candidate factor in the multivariate model-building process.

FIGURE 3.

Graphical Depiction of Interaction Effect Between Oral Capecitabine/IV Chemotherapy and Line of Therapy with the MPR as the Outcome Variable

Table 4 displays results of the multivariate GEE model of factors associated with MPR, modeled as a continuous outcome variable. In this model, patients with lung or liver metastases had a modestly but statistically significantly higher MPR (approximately 0.012 units higher on a scale of 0-1; P < 0.001) compared with patients with metastases at other locations. Similarly, patients with a CCI score at or below 9 had a slightly but significantly lower MPR (0.008 units lower; P = 0.009) compared with patients with a CCI score greater than 9. The significant interaction effect between line of therapy and type of therapy (oral capecitabine vs. IV chemotherapy) that was observed in simpler models persisted in this final multivariate model. Overall, patients receiving first-line therapy with oral capecitabine experienced an MPR approximately 0.062 units lower than patients receiving first-line IV chemotherapy (P < 0.001). The nature of the observed interaction was that as the line of therapy increased, the difference in MPR between patients receiving oral capecitabine and IV chemotherapy increased. Patients receiving fourth-line therapy and beyond experienced an MPR 0.1 units lower than patients receiving IV chemotherapy (P < 0.001).

TABLE 4.

Final Multivariate GEE Model Parameters Assessing MPR as a Continuous Outcome Variable

| Factor | Change in MPR (Beta Coefficient) | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung/liver metastases vs. metastases at other locations | 0.012 | 0.006, 0.019 | < 0.001a |

| CCI ≤ 9 vs. > 9 | -0.008 | -0.014, -0.002 | 0.009a |

| Oral capecitabine vs. IV chemotherapy | |||

| First line | -0.062 | -0.073, -0.051 | < 0.001a |

| Second line | -0.056 | -0.075, -0.037 | 0.550b |

| Third line | -0.083 | -0.11, -0.058 | 0.099b |

| Fourth line and beyond | -0.10 | -0.13, -0.082 | < 0.001b |

aThese P values can be interpreted as the significance level of the factor’s relationship with the outcome variable and MPR, modeled as a continuous variable.

bThe P values can be interpreted as the significance level of the interaction effect between line of therapy and oral/IV therapy type.

CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI = confidence interval; GEE = generalized estimating equations; IV = intravenous; MPR = medication possession ratio.

In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted the length of time that distinguished a discontinuation of treatment from a temporary break from a baseline of 60 days to 45 days and 90 days. Some parameter estimates were modestly affected, but all study inferences remained intact.

Discussion

This commercial claims-based analysis of patients with mCRC suggests that many patients received treatments not recommended by NCCN treatment guidelines across all lines of therapy. This disparity between clinical practice and evidence-based guidelines could lead to suboptimal clinical outcomes and increased costs.1,11 The treatment patterns we observed were consistent with another recently published report with respect to the most commonly prescribed chemotherapy for mCRC (FOLFOX) and the proportion of patients receiving second, third, and fourth lines of chemotherapy.12 Furthermore, this analysis determined that although adherence was relatively high among all patients, adherence to oral capecitabine was statistically lower compared to IV chemotherapy regimens. Additionally, the difference in adherence rates between IV and oral regimens increased as the line of anticancer regimen increased. The reason for this is unclear but may be related to the differences in the process of care experienced by patients receiving IV versus oral anticancer therapy.11,13-17 As many previous authors have pointed out, receiving IV chemotherapy at an infusion center is much more structured than filling a prescription for an oral medication at a local pharmacy. Future work should be dedicated to better understanding this phenomenon.

These results suggest that there should be an increased focus on improving adherence rates in patients receiving oral capecitabine. These interventions might include patients, providers, and perhaps even payers.5,18-21 Educational campaigns may raise awareness of the potential for lower adherence with oral anticancer therapy on the part of providers and might improve patients’ understanding of the importance of adherence.1,7,18,19,22-24 Additionally, changes to benefit design, where payers cover oral anticancer medications as a medical benefit as with injectable chemotherapy, might eliminate a financial barrier and thereby improve adherence.1,25 The optimal strategy to improve adherence to oral anticancer therapy is unknown and should be the focus of future studies. The most successful strategies to improve medication adherence in general have been multidimensional, and there is no reason to suspect otherwise in this clinical setting.26

Very little is known regarding the degree of nonadherence to anticancer regimens for mCRC that may still yield full clinical benefit. This fact is important to acknowledge as clinicians seek to interpret the current results. A conventional standard is to categorize all patients with adherence levels above an MPR of 0.8 as having adequate adherence levels to achieve full clinical benefit. However, there is no evidence to guide the validity of this assumption for patients receiving anticancer therapy for mCRC. Furthermore, there is no known evidence regarding what magnitude of difference in MPR between 2 groups is clinically relevant. While a statistically significant difference was detected in the adherence rates between patients receiving oral capecitabine and IV chemotherapy, we know of no evidence that would allow us to interpret the clinical relevance of the observed difference in the levels of adherence (88% and 80% on average). We view the small differences in adherence associated with patient-specific factors (e.g., CCI score, gender, metastatic disease type) to be trivial from a clinical perspective.

That being said, most clinicians would likely agree that optimizing adherence to prescribed therapy is particularly important for patients diagnosed with mCRC.6,7,23 Research has shown that adherence is suboptimal in clinical practice across a range of oral cancers therapies.1,20,27,28 Recent reports have highlighted that structured, home-based, multidisciplinary programs to improve adherence to oral anticancer agents have been shown to be effective in improving adherence, patient satisfaction, medication error rates, and management of cancer-related symptoms.5,21,22,24 Our evidence suggests that programs to improve medication adherence might prioritize patients who are taking oral anticancer agents and are also beyond the first line of therapy. From an economic perspective, a recent systematic review also highlighted that improvement to adherence with oral anticancer regimens was a key factor in considering oral anticancer regimens cost-effective.11

Limitations

There are limitations to this study that should be considered when interpreting the results. Our measures of adherence were based on pharmacy and medical procedure claims, which may not perfectly correspond with actual adherence to the studied regimens. The Optum Oncology Management claims database contains very little clinical detail outside of diagnosis codes, and inpatient claims were not available. Therefore, we have a limited knowledge of patients’ clinical condition and circumstances surrounding episodes of nonadherence. The population included in this analysis is much younger compared to U.S. colon cancer patients, with an average age at diagnosis of approximately 70 years.17 This population is also notable for having only 7% of patients over age 65 years. In addition, the impact of underrepresentation of patients from the Northeast and West regions of the United States. is unknown. We could also not assess other factors that have been shown to be associated with adherence to oral anticancer regimens, like education, social support, marital status, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (among others). Our measure of comorbidity, the CCI, is a general measure that weights cancer very highly. Therefore, it likely is limited in its ability to provide adequate weighting of patients’ clinical status among an mCRC cohort. We could not distinguish between nonadherence and deliberately chosen gaps in therapy necessitated, for example, by medication side effects or at patient request. This phenomenon could have had the effect of inflating nonadherence estimates. Lastly, since the Optum Oncology Management claims database is composed of predominantly commercially insured patients, we cannot necessarily generalize our findings to patients with different coverage types.

Conclusions

In patients with mCRC in a predominantly commercially insured population, adherence with IV chemotherapy regimens is statistically and significantly higher than oral capecitabine therapy. This finding persisted in multivariate regression adjusting for age, gender, line of therapy and CCI score. Additionally, there is evidence of an interaction effect, where medication adherence is relatively stable across the number of lines of therapy for IV chemotherapy, but adherence is statistically lower as number of lines of therapy increases for patients receiving oral capecitabine therapy. These findings could be used to support prioritization of programs to improve adherence in patients taking oral anticancer regimens beyond the first line of therapy. Future work should seek to expand knowledge of the clinical context of nonadherence to these regimens and determine if the results are repeatable in a noncommercially insured population.

Reference

- 1. Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: Oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(Suppl 3):S1-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aisner J. Overview of the changing paradigm in cancer treatment: oral chemotherapy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:S4-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goodin S, Griffith N, Chen B, et al. Safe handling of oral chemotherapeutic agents in clinical practice: recommendations from an international pharmacy panel. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, Warner E. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Onc. 1997;15:110-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCue DA, Lohr LK, Pick AM. Improving adherence to oral cancer therapy in clinical practice. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34(5):481-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, Winer EP. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(9):652-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mathes T, Pieper D, Antoine SL, Eikermann M. Adherence influencing factors in patients taking oral anticancer agents: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38(3):214-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, Malone DC. Measurements of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1280-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, Benner J, Gwadry-Sridhar F, Nichol M. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health.2007;10:3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13-22. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smieliauskas F, Chien CR, Shen C, Geynisman DM, Shih YC. Cost-effectiveness analyses of targeted oral anti-cancer drugs: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(7):651-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Abrams TA, Meyer G, Schrag D, Meyerhardt JA, Moloney J, Fuchs CS. Chermotherapy usage patterns in a US-wide cohort of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(2):1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bordonaro S, Romano F, Lanteri E, et al. Effect of a structured, active, home-based cancer-treatment program for the management of patients on oral chemotherapy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:917-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Geynisman DM, Wickersham KE. Adherence to targeted oral anticancer medications. Discov Med. 2013;15(83):231-41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(1):56-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spoelstra SL, Given BA, Given CW, Grant M, Sikorskii A, You M, Decker V. An intervention to improve adherence and management of symptoms for patients prescribed oral chemotherapy agents. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(1):18-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abrams TA, Meyer G, Schrag D, Meyerhardt JA, Moloney J, Fuchs CS. Chemotherapy usage patterns in a US-wide cohort of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(2):djt371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Felton MA, van Londen G, Marcum ZA. Medication adherence to oral cancer therapy: the promising role of the pharmacist. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2014;11:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, McDonald HP, Yao X. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD000011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haynes RB, McDonald HP, Garg AX. Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: clinical applications. JAMA. 2002;288(22):2880-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Spoelstra SL, Given BA, Given CW, et al. Issues related to overadherence to oral chemotherapy or targeted agents. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:604-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bordonaro S, Romano F, Lanteri E, et al. Effect of a structured, active, home-based cancer-treatment program for the management of patients on oral chemotherapy. Patient Prefer Adherence.2014;8:917-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hartigan K. Patient education: the cornerstone of successful oral chemotherapy treatment. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7(6 Suppl):21-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong SF, Bounthavong M, Nguyen C, Bechtoldt K, Hernandez E. Implementation and preliminary outcomes of a comprehensive oral chemotherapy management clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(11):960-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Curtiss FR. Pharmacy benefit spending on oral chemotherapy drugs. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12(7):570-07. Available at: http://amcp.org/data/jmcp/contemporary_subjects_570_577.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Onc. 2010;28(27):4120-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(2):529-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]