Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Abiraterone acetate (AA) and enzalutamide (ENZ) are oral therapies offering survival benefit to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients. Despite the availability of multiple treatment options for mCRPC, there is a lack of information on the effect that being initiated on AA or ENZ has on the combined prostate cancer treatment duration.

OBJECTIVE:

To compare the combined duration of prostate cancer treatments of patients initiated on AA with that of patients initiated on ENZ.

METHODS:

Truven Health MarketScan Research Databases from March 2012 to December 2014 were used to identify males with prostate cancer initiated on AA or ENZ (index therapy). Baseline characteristics were assessed during the 6 months pre-index. Inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTWs) were used to reduce baseline confounding. Treatment duration spanned from the index date to the earliest of treatment discontinuation (defined as a > 60-day gap in treatment), 24 months post-index, health plan disenrollment, or end of data. Weighted Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazard models were used to compare the combined duration of mCRPC treatments (AA, ENZ, chemotherapy, sipuleucel-T, and radium 223) and any prostate cancer treatments (mCRPC, hormonal, and corticosteroid treatments) between patients initiated on either AA or ENZ.

RESULTS:

A total of 2,591 patients initiated on AA and 807 patients initiated on ENZ were selected for the study. Patients’ characteristics were generally well balanced after IPTW. At 3 months, patients initiated on AA were associated with fewer discontinuations of mCRPC treatments (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.73, P = 0.004) or of any prostate cancer treatments (HR = 0.61, P = 0.002), compared with patients initiated on ENZ. This result was maintained at 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months for mCRPC treatments (HR = 0.75, P < 0.001) and for any prostate cancer treatments (HR = 0.69, P < 0.001). Median duration of mCRPC treatments was 4.1 months longer for patients initiated on AA compared with those initiated on ENZ (18.3 vs. 14.2 months, P < 0.001) and similarly, the median duration of any prostate cancer treatment was longer for patients initiated on AA compared with those initiated on ENZ (not reached vs. 22.2 months, P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

In this study, patients initiated on AA, compared with those initiated on ENZ, had a longer combined duration of mCRPC or prostate cancer treatments.

What is already known about this subject

The prognosis of patients diagnosed with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) is low.

Docetaxel was the mainstay of treatment for almost a decade, but since 2010, several alternatives such as abiraterone acetate (AA) and enzalutamide (ENZ) have broadened mCRPC treatment options and have shown increased overall survival in patients in a pre- and post-docetaxel setting.

Patients receiving AA then ENZ were shown to have better progression-free and overall survival compared with patients receiving ENZ then AA.

What this study adds

Within a large population of commercially insured and Medicare patients, and after treatment initiation, duration of combined mCRPC treatments was significantly longer among patients initiated on AA compared with patients initiated on ENZ.

After treatment initiation, duration of overall prostate cancer treatment (mCRPC treatments, androgen deprivation therapy, and corticosteroids) was significantly longer among patients initiated on AA compared with patients initiated on ENZ.

Prostate cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality in the United States.1 The American Cancer Society has estimated that 180,890 new cases of prostate cancer will be diagnosed in 2016 and that 26,120 men will die of this disease in 2016. Approximately 1 in 7 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer during his lifetime.2 For approximately 20% to 30% of patients treated for localized disease, the cancer will eventually progress.3 Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is the mainstay treatment for advanced prostate cancer, but for the majority of patients it results in disease control for only 12 to 18 months. Patients with a castration level of testosterone and a progressive prostate cancer that has spread to other parts of the body are metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients.

Docetaxel has been the standard of care for men with mCRPC for many years,4 but in recent years, treatment options for mCRPC have expanded. Prolonged survival rates, pain reduction, and improvement in quality of life have been achieved by using new second-line drugs such as abiraterone acetate (AA), enzalutamide (ENZ), cabazitaxel, radium-223, and sipuleucel-T.5-13 Both AA and ENZ are new oral medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. AA, a pro-drug of abiraterone, is a CYP17 inhibitor that blocks androgen biosynthesis.14 ENZ belongs to the androgen receptor inhibitor class, of which bicalutamide and flutamide are also members. Androgen receptor inhibitors bind to the androgen receptor and block signaling.15

The current recommendations from various cancer organizations and health care governmental organizations include continued ADT therapy and, in addition, docetaxel and/or some of the more recent mCRPC targeted agents listed above.16,17 A recent study showed that, compared with patients receiving ENZ and then AA, patients receiving AA and then ENZ had better progression-free and overall survival.18 It is thus common that mCRPC patients may receive, concomitantly or consecutively, multiple prostate cancer treatments over the course of their advanced disease.19,20 However, reasons for any treatment discontinuation pertain to either disease progression or to unacceptable adverse events.21 The present study aimed to compare the combined duration of prostate cancer treatments for patients initiated on AA with that of patients initiated on ENZ.

Methods

Data Sources

The Truven Health MarketScan Research Databases from March 2012 to December 2014 were used to conduct this study. The Truven Health MarketScan Research Databases combine 2 databases (i.e., the Commercial Claims and Encounters database, and the Medicare Supplemental and Coordination of Benefits database) to cover all age groups and contain claims from approximately 100 employers, health plans, and government and public organizations representing about 30 million covered lives.

All data collected from each database were de-identified in compliance with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Study Design and Patient Selection

A retrospective study design was used and prostate cancer patients treated with AA or ENZ from September 1, 2012, to December 31, 2014, were selected to form the study population. The index date was defined as the date of the first claim for AA or ENZ after September 1, 2012, (date of ENZ availability in the United States) with no prior evidence of treatment with AA or ENZ. Classification into the AA cohort or the ENZ cohort was based on the index treatment. Patients were included in the study population if they had at least 6 months of continuous eligibility pre-index (baseline period) and if they had at least 1 prostate cancer diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 185.xx) during the period of continuous eligibility. The choice of the length of the pre-index period was driven by the need to have enough time to assess baseline demographics and clinical characteristics while retaining a large number of patients. The observation period spanned the index date until the date of health plan disenrollment or the end of data availability (December 31, 2014), whichever occurred first.

Study Outcomes

The outcome of this study was the total duration of continuous prostate cancer treatment, which was defined as the time between the index date and the last day of supply of the last prostate cancer treatment claim before discontinuation of treatment. Discontinuation of treatment was defined as having a period of 60 days following a prostate cancer treatment claim without another claim for a treatment. The first discontinuation was considered in the analysis.

Treatment duration was evaluated for 3 groups of prostate cancer treatments: (a) any prostate cancer treatments observed post-index, including mCRPC treatments, hormonal therapy, and corticosteroids; (b) any mCRPC treatments observed post-index, including AA, ENZ, chemotherapy, sipuleucel-T, and radium 223; and (c) index mCRPC treatment (i.e., AA for patients initiated on AA and ENZ for patients initiated on ENZ).

Statistical Analysis

Because of the nonexperimental nature of the study, patients initiated on AA are likely to have different demographics and baseline clinical characteristics than patients initiated on ENZ. Comparisons between patients initiated on AA and ENZ were adjusted using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTWs),22 a weighting method used to minimize potential baseline confounding and selection bias while retaining a sufficiently large study population.23-28 The IPTW used weights derived from the propensity score to create a weighted population that retained all patients and made them similar to the overall study population, such that the distribution of covariates was independent of treatment. Therefore, results obtained with IPTW should be interpreted as the average treatment effect (ATE) among the overall population. The ATE among the treated is another approach that could have been chosen; however, the ATE approach was chosen because the results show the expected treatment effect for any randomly drawn individual from the overall population.

The propensity score (PS), defined as the probability of initiating AA treatment, was estimated using a multivariable logistic regression model conditional on the baseline covariates (i.e., age, region, quarter of the index date, payment type, plan type, physician specialty, baseline metastasis, Charlson Comorbidity Index, individual comorbidities, prostate cancer treatments, and number of unique hormonal agents received). IPTWs were then calculated as the inverse of patients’ estimated probabilities of having their observed initiation treatment (i.e., 1/PS for the AA group and 1/(1-PS) for the ENZ group). Finally, the normalized IPTWs were calculated by dividing each IPTW by the overall mean IPTW so that the sum of weights was equivalent to the overall sample size. Moreover, the normalization of IPTWs could reduce the variance of estimators.29

Descriptive statistics were used to report patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and treatment patterns. Means, standard deviations, and medians were used to describe continuous variables; frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Standardized differences were used to compare baseline demographics and clinical characteristics between weighted cohorts and assess the quality of the IPTW, with the goal being to achieve clinically and statistically well-balanced cohorts according to an accepted threshold of < 10%.30,31

For treatment patterns, statistical comparisons between groups were made using weighted chi-squared tests for categorical variables and weighted 2-sided Student’s t-tests for continuous variables. Although mean weighted treatment duration can be compared between the 2 cohorts, time-to-event analyses can better take into account patient censoring and time-to-treatment discontinuation; therefore, weighted Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival curves and Cox proportional hazards models (i.e., time-to-event analyses) were used to compare the KM rates and the hazards of discontinuing prostate cancer treatment (based on the 3 definitions above) between the 2 cohorts. Similarly to weighted treatment duration, weighted KM survival curves used the patient-level weights created by the IPTW method described above. The rates and hazards of both groups were compared at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months using log-rank tests, hazard ratios (HRs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and P values. Study analyses were performed with SAS software package 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata software package 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Among 714,040 patients with prostate cancer, a total of 3,398 patients (without prior evidence of treatment with AA or ENZ) were initiated on AA or ENZ, had at least 6 months of continuous eligibility pre-index, and had at least 1 prostate cancer (PC) diagnosis during the period of continuous eligibility. Of them, 2,591 patients were initiated on AA (AA patients) and 807 patients were initiated on ENZ (ENZ patients).

Table 1 shows the unweighted and weighted demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of the study population. Prior to weighting, the comparison of AA and ENZ patients revealed large differences in several characteristics, including age, comorbidities, and baseline medications. For the weighted cohorts, which were used for subsequent analyses, the weighted population was equivalent to 1,718 patients for the AA cohort and 1,680 patients for the ENZ cohort. The median IPTW was 0.61 for AA patients and 1.68 for ENZ patients, with the interquartile range of 0.57-0.69 and 1.11-2.44, respectively (data not shown). The maximum weight was 3.19 for AA patients and 15.37 for ENZ patients (data not shown); therefore, no extreme weights were driving the results in the current study. Weighted cohorts appeared to have a similar age, as well as a similar proportion of patients with prior use of chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or corticosteroids.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| Unweighted Population | Weighted Populationa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA Cohort | ENZ Cohort | Standardized Difference (%) | AA Cohort | ENZ Cohort | Standardized Difference (%) | |||||

| N = 2,591 | N = 807 | N = 1,718 | N = 1,680 | |||||||

| Age, years, mean ± SD [median] | 73.8 ± 10.5 [75.0] | 72.8± 10.8 [73.0] | 9.2 | 73.5± 10.4 [74.0] | 73.7± 10.8 [75.0] | 1.4 | ||||

| Age categories, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 35-44 years | 3 | (0.1) | 2 | (0.2) | 3.1 | 2 | (0.1) | 2 | (0.1) | 0.9 |

| 45-54 years | 69 | (2.7) | 36 | (4.5) | 9.7 | 47 | (2.7) | 66 | (3.9) | 6.7 |

| 55-64 years | 546 | (21.1) | 171 | (21.2) | 0.3 | 367 | (21.4) | 320 | (19.1) | 5.8 |

| 65-74 year s | 669 | (25.8) | 222 | (27.5) | 3.8 | 453 | (26.4) | 448 | (26.7) | 0.7 |

| ≥ 75 years | 1,304 | (50.3) | 376 | (46.6) | 7.5 | 849 | (49.4) | 843 | (50.2) | 1.5 |

| Region, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Northeast | 617 | (23.8) | 165 | (20.4) | 8.1 | 396 | (23.0) | 399 | (23.8) | 1.7 |

| North Central | 706 | (27.2) | 217 | (26.9) | 0.8 | 467 | (27.2) | 463 | (27.5) | 0.8 |

| South | 789 | (30.5) | 276 | (34.2) | 8.0 | 539 | (31.4) | 504 | (30.0) | 2.9 |

| West | 464 | (17.9) | 136 | (16.9) | 2.8 | 303 | (17.6) | 300 | (17.9) | 0.5 |

| Unknown | 15 | (0.6) | 13 | (1.6) | 9.9 | 14 | (0.8) | 14 | (0.8) | 0.3 |

| Year of index date, n (%) | ||||||||||

| 2012 | 418 | (16.1) | 127 | (15.7) | 1.1 | 277 | (16.1) | 288 | (17.2) | 2.8 |

| 2013 | 1,400 | (54.0) | 280 | (34.7) | 39.7 | 849 | (49.4) | 821 | (48.9) | 1.1 |

| 2014 | 773 | (29.8) | 400 | (49.6) | 41.2 | 592 | (34.5) | 571 | (34.0) | 1.0 |

| Payment type, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 1,994 | (77.0) | 607 | (75.2) | 4.1 | 1,317 | (76.7) | 1,306 | (77.8) | 2.6 |

| Commercial | 597 | (23.0) | 200 | (24.8) | 4.1 | 401 | (23.3) | 374 | (22.2) | 2.6 |

| Baseline metastasis, n (%) | 1,925 | (74.3) | 612 | (75.8) | 3.6 | 1,284 | (74.8) | 1,270 | (75.6) | 2.0 |

| Baseline Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean ± SD [median] | 6.0 ± 2.3 [6.0] | 6.1 ± 2.3 [6.0] | 3.6 | 6.0 ± 2.3 [6.0] | 6.0 ± 2.3 [6.0] | 0.0 | ||||

| Baseline comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||||||

| CNS conditions | ||||||||||

| Cognitive disorders | 5 | (0.2) | 5 | (0.6) | 6.7 | 6 | (0.4) | 7 | (0.4) | 1.3 |

| Fatigue/asthenia | 396 | (15.3) | 129 | (16.0) | 1.9 | 268 | (15.6) | 264 | (15.7) | 0.3 |

| Pain | 255 | (9.8) | 92 | (11.4) | 5.1 | 179 | (10.4) | 183 | (10.9) | 1.5 |

| Diabetes | 587 | (22.7) | 211 | (26.1) | 8.1 | 404 | (23.5) | 372 | (22.1) | 3.3 |

| Depression | 135 | (5.2) | 59 | (7.3) | 8.7 | 100 | (5.8) | 104 | (6.2) | 1.6 |

| Hypertension | 1,316 | (50.8) | 396 | (49.1) | 3.4 | 863 | (50.2) | 826 | (49.2) | 2.2 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1,004 | (38.7) | 317 | (39.3) | 1.1 | 669 | (38.9) | 655 | (39.0) | 0.1 |

| Baseline malignant neoplasms, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Lip, oral cavity, and pharynx | 3 | (0.1) | 3 | (0.4) | 5.2 | 3 | (0.2) | 5 | (0.3) | 1.7 |

| Digestive organs and peritoneum | 89 | (3.4) | 29 | (3.6) | 0.9 | 59 | (3.4) | 60 | (3.6) | 1.0 |

| Respiratory and intrathoracic organs | 59 | (2.3) | 18 | (2.2) | 0.3 | 39 | (2.3) | 40 | (2.4) | 0.8 |

| Bone, connective tissue, skin, and breast | 214 | (8.3) | 55 | (6.8) | 5.5 | 143 | (8.3) | 151 | (9.0) | 2.4 |

| Genitourinary organs (excluding 185.xx) | 151 | (5.8) | 42 | (5.2) | 2.7 | 98 | (5.7) | 91 | (5.4) | 1.4 |

| Other and unspecified sites | 42 | (1.6) | 15 | (1.9) | 1.8 | 29 | (1.7) | 36 | (2.1) | 3.2 |

| Lymphatic and hematopoietic tissue | 68 | (2.6) | 22 | (2.7) | 0.6 | 45 | (2.6) | 43 | (2.6) | 0.3 |

| Baseline prostate cancer treatments, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Chemotherapy | 373 | (14.4) | 204 | (25.3) | 27.5 | 298 | (17.4) | 311 | (18.5) | 3.0 |

| Docetaxel | 299 | (11.5) | 161 | (20.0) | 23.2 | 237 | (13.8) | 248 | (14.7) | 2.8 |

| Cabazitaxel | 42 | (1.6) | 33 | (4.1) | 14.9 | 41 | (2.4) | 43 | (2.5) | 1.0 |

| Other chemotherapy | 372 | (14.4) | 203 | (25.2) | 27.4 | 298 | (17.3) | 307 | (18.3) | 2.5 |

| Hormonal treatmentsb | 2,236 | (86.3) | 658 | (81.5) | 13.0 | 1,457 | (84.8) | 1,415 | (84.2) | 1.6 |

| Number of unique hormonal agents received, mean ± SD [median] | 1.3 ± 0.7 [1.0] | 1.2± 0.7 [1.0] | 23.6 | 1.3± 0.8 [1.0] | 1.3± 0.8 [1.0] | 0.6 | ||||

| Sipuleucel-T | 150 | (5.8) | 62 | (7.7) | 7.6 | 104 | (6.1) | 105 | (6.3) | 0.9 |

| Radium 223 | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | – | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | – |

| Corticosteroids | 1,419 | (54.8) | 344 | (42.6) | 24.5 | 894 | (52.0) | 860 | (51.2) | 1.7 |

| Prednisone | 1,145 | (44.2) | 221 | (27.4) | 35.6 | 688 | (40.0) | 648 | (38.6) | 2.9 |

| Dexamethasone | 446 | (17.2) | 219 | (27.1) | 24.1 | 344 | (20.0) | 359 | (21.4) | 3.4 |

| Other corticosteroids | 416 | (16.1) | 126 | (15.6) | 1.2 | 276 | (16.1) | 273 | (16.3) | 0.5 |

aBaseline characteristics for the weighted populations were obtained by using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTWs). The IPTWs were estimated based on propensity score. Variables used in the propensity score calculation included the following baseline characteristics: age, region, quarter of the index date, payment type, plan type, physician specialty, baseline metastasis, Charlson Comorbidity Index, comorbidities (cognitive disorders, fatigue/asthenia, pain, diabetes, depression, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease), prostate cancer treatments (cabazitaxel, docetaxel, other chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, sipuleucel-T, prednisone, dexamethasone, other corticosteroids), and number of unique hormonal agents received.

bHormonal therapy includes LhRH/GnRH, estrogens, antiandrogens, and adrenal androgen blockers.

AA = abiraterone acetate; CNS = central nervous system; ENZ = enzalutamide; SD = standard deviation.

Treatment Patterns

Table 2 shows that the length of observation was similar between both weighted cohorts (mean ± standard deviation [SD], AA vs. ENZ: 313.4 ± 222.8 days vs. 310.3 ± 218.8 days, P = 0.723), but relative to ENZ patients, AA patients had a longer duration of continuous mCRPC treatment (mean ± SD, AA vs. ENZ: 240.0 ± 194.3 days vs. 221.1 ± 184.5 days, P = 0.013) and a longer duration of PC treatment (mean ± SD [median], AA vs. ENZ: 270.7 ± 207.3 [218] days vs. 249.6 ± 197.0 [183.0] days, P = 0.009), without taking into account patient censoring. Chemotherapy use (AA vs. ENZ: 18.1% vs. 15.4%, P = 0.035) and corticosteroid use (AA vs. ENZ: 90.2% vs. 49.1%, P < 0.001) were more frequent in AA patients compared with ENZ patients. Additional details are provided in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Treatment Patterns Observed in Weighted mCRPC Cohorts Initiated on AA or ENZ

| Weighted Populationa | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA Cohort | ENZ Cohort | |||||

| Weighted N = 1,718 | Weighted N = 1,680 | P Valueb | ||||

| Length of the follow-up period, days, mean ± SD [median] | 313.4 ± 222.8 [269.0] | 310.3 ± 218.8 [269.0] | 0.723 | |||

| Duration of treatment, days, mean ± SD [median]c | ||||||

| Index medication | 195.0 ± 168.9 [144.0] | 184.7 ± 162.4 [134.0] | 0.121 | |||

| mCRPC treatmentd | 240.0 ± 194.3 [184.0] | 221.1 ± 184.5 [159.0] | 0.013g | |||

| Any PC treatmente | 270.7 ± 207.3 [218.0] | 249.6 ± 197.0 [183.0] | 0.009g | |||

| Medication taken during the observation period, n (%) | ||||||

| AA | 1,718 | (100.0) | 334 | (19.9) | – | |

| ENZ | 461 | (26.8) | 1,680 | (100.0) | – | |

| Chemotherapy | 311 | (18.1) | 258 | (15.4) | 0.035g | |

| Sipuleucel-T | 31 | (1.8) | 42 | (2.5) | 0.165 | |

| Hormonal therapyf | 1,057 | (61.5) | 1,068 | (63.6) | 0.220 | |

| Corticosteroids | 1,551 | (90.2) | 825 | (49.1) | < 0.001g | |

| Concomitant use during index treatment | 1,511 | (97.4) | 675 | (81.8) | < 0.001g | |

| Prednisone | 1,460 | (96.6) | 477 | (70.7) | < 0.001g | |

| Nonconcomitant use | 511 | (32.9) | 460 | (55.8) | < 0.001g | |

aTreatment patterns for the weighted populations were obtained by using inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTWs). The IPTWs were estimated based on propensity score. Variables used in the propensity score calculation included the following baseline characteristics: age, region, quarter of the index date, payment type, plan type, physician specialty, baseline metastasis, Charlson Comorbidity Index, comorbidities (cognitive disorders, fatigue/asthenia, pain, diabetes, depression, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease), prostate cancer treatments (cabazitaxel, docetaxel, other chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, sipuleucel-T, prednisone, dexamethasone, other corti-costeroids), and number of unique hormonal agents received.

bP value was estimated using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

cContinuous treatment was defined as having no more than 60 days between a claim and the last day of supply of the previous claim.

dmCRPC treatments include AA, ENZ, chemotherapy, sipuleucel-T, and radium 223.

eAny prostate cancer treatments include AA, ENZ, chemotherapy, sipuleucel-T, radium 223, hormonal therapy, and corticosteroids.

fHormonal therapy includes leuprolide, bicalutamide, histrelin, triptorelin, goserelin, buserelin, nafarelin, flutamide, nilutamide, cyproterone, estrogen, diethylstilbestrol, ketoconazole, and aminoglutethimide.

gSignificant at the 5% level.

AA = abiraterone acetate; ENZ = enzalutamide; mCRPC = metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PC = prostate cancer; SD = standard deviation.

Time to Discontinuation of Prostate Cancer Treatment

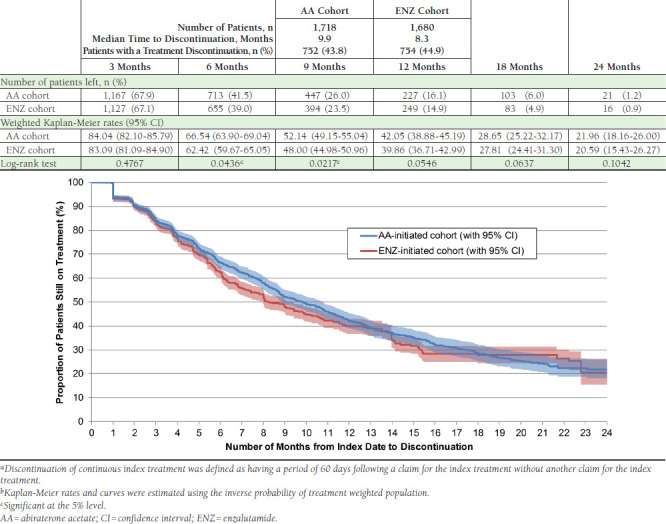

Figure 1 presents the time to discontinuation of index treatment. Approximately the same number of patients discontinued index treatment in both cohorts (AA vs. ENZ: 43.8% vs. 44.9%) in the observation period. However, ENZ patients discontinued treatment faster, as highlighted by the shorter median time to discontinuation (AA vs. ENZ: 9.9 vs. 8.3 months) and lower proportions of patients still on index treatment at 6 and 9 months (6 months, AA vs. ENZ: 66.5% vs. 62.4%, P = 0.044; 9 months, AA vs. ENZ: 52.1% vs. 48.0%, P = 0.022).

FIGURE 1.

Time from Index Date to Discontinuation of Index Treatmenta,b

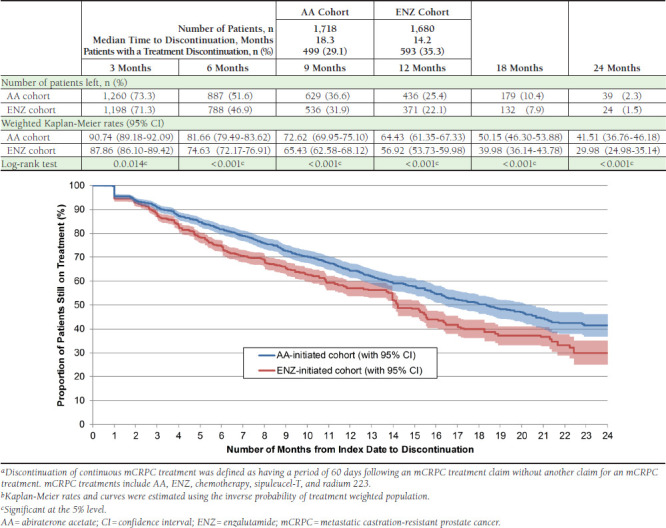

Figure 2 and Figure 3 present the time to discontinuation of mCRPC treatment and any prostate cancer treatment, respectively. At 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months, lower proportions of AA patients had a discontinuation of any mCRPC or prostate cancer treatment compared with ENZ patients (proportion of patients still on mCRPC treatment at 12 months, AA vs. ENZ: 64.4% vs. 56.9%, P < 0.001; proportion of patients still on any prostate cancer treatment at 12 months, AA vs. ENZ: 80.3% vs. 72.8%, P < 0.001). Moreover, fewer AA patients had an mCRPC treatment discontinuation (AA vs. ENZ: 29.1% vs. 35.3%), and the median time to discontinuation was 4.1 months longer for the AA cohort compared with the ENZ cohort (AA vs. ENZ: 18.3 vs. 14.2 months). Similarly, fewer AA patients had a discontinuation of any prostate cancer treatment (AA vs. ENZ: 17.7% vs. 23.5%), and only the ENZ cohort had enough discontinuations to calculate a median time to discontinuation (22.2 months). Table 3 presents the hazard ratio of discontinuing prostate cancer treatment using Cox proportional hazards models at different time points. At 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months, as well as for the entire observation period, AA patients had a significant reduction in the hazard of discontinuing mCRPC treatments (12-month HR [95% CI]: 0.76 [0.66-0.86], P < 0.001) or any prostate cancer treatments (12-month HR [95% CI]: 0.66 [0.55-0.78], P < 0.001) compared with ENZ patients. Additionally, at 6 and 9 months, AA patients had a significant reduction in the hazard of discontinuing index treatment compared with ENZ patients.

FIGURE 2.

Time from Index Date to Discontinuation of mCRPC Treatmenta,b

FIGURE 3.

Time from Index Date to Discontinuation of Any PC Treatmenta,b

TABLE 3.

Impact of the Index Treatment (AA vs. ENZ) on the Time to Discontinuation of PC Treatmenta

| Weighted Cox Proportional Hazard Model AA Cohort: N = 1,718 ENZ Cohort: N = 1,680 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95 % CI | P Value | |

| Discontinuation of index treatment | |||

| 3 months | 0.91 | (0.77-1.08) | 0.297 |

| 6 months | 0.88 | (0.77-1.00) | 0.045d |

| 9 months | 0.88 | (0.79-0.98) | 0.024d |

| 12 months | 0.90 | (0.81-1.00) | 0.056 |

| 18 months | 0.91 | (0.82-1.01) | 0.065 |

| 24 months | 0.92 | (0.83-1.02) | 0.106 |

| Overall | 0.92 | (0.83-1.02) | 0.106 |

| Discontinuation of mCRPC treatmentb | |||

| 3 months | 0.73 | (0.59-0.91) | 0.004d |

| 6 months | 0.70 | (0.60-0.83) | <0.001d |

| 9 months | 0.74 | (0.64-0.85) | <0.001d |

| 12 months | 0.76 | (0.66-0.86) | <0.001d |

| 18 months | 0.75 | (0.66-0.85) | <0.001d |

| 24 months | 0.75 | (0.66-0.84) | <0.001d |

| Overall | 0.75 | (0.67-0.85) | <0.001d |

| Discontinuation of any PC treatmentc | |||

| 3 months | 0.61 | (0.45-0.83) | 0.002d |

| 6 months | 0.62 | (0.50-0.78) | <0.001d |

| 9 months | 0.61 | (0.51-0.74) | <0.001d |

| 12 months | 0.66 | (0.55-0.78) | <0.001d |

| 18 months | 0.68 | (0.59-0.80) | <0.001d |

| 24 months | 0.69 | (0.59-0.80) | <0.001d |

| Overall | 0.69 | (0.60-0.80) | <0.001d |

aDiscontinuation of treatment was defined as having a period of 60 days following a PC treatment claim without another claim for a PC treatment.

bmCRPC treatments include AA, ENZ, chemotherapy, sipuleucel-T, and radium 223.

cPC treatments include AA, ENZ, chemotherapy, sipuleucel-T, radium 223, hormonal therapy, and corticosteroids.

dSignificant at the 5% level.

AA = abiraterone acetate; CI = confidence interval; ENZ = enzalutamide; mCRPC = metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; PC = prostate cancer.

To account for the fact that ENZ was approved for post-chemotherapy patients only until September 10, 2014, (date when it was approved for chemotherapy-naïve patients) and that chemotherapy-naïve patients identified before that time point had a zero probability of receiving ENZ, sensitivity analyses were performed among the subset of patients with prior chemotherapy treatment and the subset of patients with prior docetaxel treatment. In both cases and despite reduced sample size, similar trends were observed, and results revealed that AA patients had a significant reduction in the hazard of discontinuing mCRPC treatments or any prostate cancer treatments compared with ENZ patients.

Discussion

This real-world retrospective observational study of mCRPC patients, controlling for baseline confounding and selection bias with IPTW, demonstrates lower discontinuation rates of mCRPC or prostate cancer therapies in patients whose first oral mCRPC therapy was AA compared with patients whose first oral mCRPC therapy was ENZ. AA and ENZ are, to date, the only 2 oral therapies approved for treatment of mCRPC. The initiation of AA therapy was associated with a 25% to 31% decrease in the hazard of discontinuing prostate cancer treatments compared with the initiation of ENZ therapy.

Many studies have shown that AA and ENZ can prolong overall survival in mCRPC patients. De Bono et al. (2011) showed that post-chemotherapy patients treated with AA and prednisone had a 35.4% reduction in the risk of death and a longer median overall survival compared with patients treated with placebo and prednisone (median overall survival: 14.8 vs. 10.9 months, HR [95% CI]: 0.65 [0.54-0.77], P < 0.001).6 The median duration of treatment was 8 months for AA and prednisone patients and 4 months for placebo and prednisone patients.

The same conclusions were drawn by Ryan et al. (2015) among chemotherapy-naïve patients.32 Patients treated with AA and prednisone had a 19.0% reduction in the risk of death compared with patients treated with placebo and prednisone (median overall survival: 34.7 vs. 30.3 months, HR [95% CI]: 0.81 [0.70-0.93], P = 0.003). The median duration of treatment was 13.8 months for AA patients and 8.3 months for placebo patients. Scher et al. (2012) showed that patients who received previous chemotherapy and were treated with ENZ had a 37.0% reduction in the risk of death and a longer median overall survival compared with patients treated with placebo (median overall survival: 18.4 vs. 13.6 months, HR [95% CI]: 0.63 [0.53-0.75], P < 0.001).8 The median duration of treatment was 8.3 months for ENZ patients and 3.0 months for placebo patients. Another study found that, among chemotherapy-naïve patients, patients treated with ENZ had a 23% reduction in the risk of death and a longer median overall survival compared with patients treated with placebo (median overall survival: 35.3 vs. 31.3 months, HR [95% CI]: 0.77 [0.67-0.88]).15

A recent trial suggested that, in contrast to ADT continuous therapy, intermittent ADT therapy may increase the risk of death.33 Moreover, results of a recent study by Sonpavde et al. (2015) seem to confirm that longer continuous treatment could be associated with better survival, as mCRPC patients treated with a sequence of 3 agents (docetaxel-cabazitaxel-AA or docetaxel-AA-cabazitaxel) had a 79% reduction in the risk of death (HR [95% CI]: 0.21 [0.09-0.48], P < 0.001) compared with mCRPC patients treated with a sequence of 2 agents (docetaxel-cabazitaxel or docetaxel-AA).34 Findings from these studies are in line with the results on the duration of treatment from the current study. However, further research with real-world data on mortality is needed to confirm the association between duration of treatment and overall survival.

The longer duration of PC treatment for patients initiated on AA may also suggest that starting AA first leads to more treatment options for future lines of therapy following AA. Treatment patterns from Table 2 seem to support this statement, as more patients initiated on AA used ENZ or chemotherapy afterward compared with patients initiated on ENZ using AA or chemotherapy afterward. The study from Maughan et al. (2016) also seems to concur with this statement, as it showed that patients receiving AA and then ENZ had better progression-free and overall survival compared with patients receiving ENZ and then AA.18 In the case of patients initiated on AA in our study, the observed longer combined duration of treatment may also be the result of a residual effect associated with AA after treatment stopped, known as the antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome. Studies have reported that in some patients treated with AA, this syndrome occurs post-treatment, which leads to a decrease in prostate-specific antigen and overall clinical improvement.35,36 One study even showed that patients having antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome following AA treatment had better overall survival.37

Moreover, potential reasons for treatment discontinuation could include the development of central nervous system (CNS) conditions such as fatigue and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome events, though the latter is infrequent.15,38 In the literature, advanced prostate cancer has often been associated with CNS conditions such as fatigue.39,40 Results from various trials evaluating the effectiveness of ENZ reported an association between ENZ and several CNS complications, particularly fatigue.8,9,41 Conversely, a clinical trial reported an improvement in fatigue for patients treated with AA and prednisone compared with patients treated with prednisone alone in a population of post-docetaxel patients.42 In addition, Pilon et al. (2015) found that AA patients had a lower likelihood of reporting CNS conditions than ENZ patients (median time to CNS condition, AA vs. ENZ: 15.6 vs. 12.2 months, P = 0.038).43 Additional analyses to assess the impact that CNS conditions may have on the duration of treatment are needed.

Limitations

This study is subject to certain limitations. First, as is the case with claims databases, the Truven Health MarketScan Research Databases may have contained inaccuracies or omissions in procedures, diagnoses, or costs. Second, it was assumed that a claim for mCRPC drugs indicated their use. However, patients might not have adhered to the mCRPC treatment regimen as prescribed; consequently, further studies on treatment adherence are required. Third, the date of death was not available in the Truven Health MarketScan Research Databases; therefore, further studies on the effect that the treatment sequencing has on overall survival are warranted. Fourth, it should be noted that AA is approved in the United States for use in combination with prednisone for the treatment of mCRPC. However, concomitant use of prednisone was not required for inclusion in the AA cohort used in this analysis. Fifth, while the current study results suggest that starting AA first over ENZ leads to longer combined therapy duration, reasons for stopping subsequent therapies may not be related to the effectiveness of the initial therapy.

Finally, as with all retrospective administrative claims data, the study results may be subject to residual confounding due to unmeasured confounders because information is limited to the variables available in the database (e.g., laboratory results were not available). This could result in biased PSs and affect the IPTW scheme.

Conclusions

In this large, real-world, retrospective observational study, KM estimates, median time to discontinuation, and HRs showed that mCRPC patients initiated on AA had a longer combined duration of prostate cancer treatment, compared with patients initiated on ENZ. Further research is needed to assess the overall survival of patients initiated on AA or ENZ in the real-world setting and its link to the duration of treatment.

References

- 1.Kohli M, Tindall DJ.. New developments in the medical management of prostate cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):77-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Key statistics for prostate cancer. 2016. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(5):411-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saad F, Hotte SJ.. Guidelines for the management of castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4(6):380-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ang JE, Olmos D, de Bono JS.. CYP17 blockade by abiraterone: further evidence for frequent continued hormone-dependence in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(5):671-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(21):1995-2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, de Bono JS, et al. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer without previous chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):138-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1187-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(5):424-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graff JN, Chamberlain ED.. Sipuleucel-T in the treatment of prostate cancer: an evidence-based review of its place in therapy. Core Evid. 2014;10:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker C, Nilsson S, Heinrich D, et al. Alpha emitter radium-223 and survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(3):213-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Recine F, Ceresoli GL, Baciarello G, Cerbone L, Calabrò F.. Improvement in survival and quality of life with new therapeutic agents in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: comparison among the results. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;59(4):400-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zytiga (abiraterone acetate) tablets. Janssen Biotech, Inc. 2016. Available at: http://www.zytiga.com/shared/product/zytiga/zytiga-prescribing-information.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xtandi (enzalutamide) capsules for oral use. Astellas Pharma U.S., Inc. 2016. Available at: https://www.astellas.us/docs/us/12A005-ENZ-WPI.pdf?v=1. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. 2014. Available at: http://www.cancer.net/research-and-advocacy/asco-care-and-treatment-recommendations-patients/treatment-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Prostate Cancer. V1.2015. 2015. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#prostate. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maughan BL, Suzman DL, Nadal RM, Bassi S, Antonarakis ES.. Optimal sequencing of enzalutamide and abiraterone in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Poster presented at: ASCO 2016 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; January 7-9, 2016; San Francisco, CA. Available at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/158546-172. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sartor O, Gillessen S.. Treatment sequencing in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 16(3):426-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis L, Lafeuille M-H, Gozalo L, et al. Treatment patterns of new meta-static castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) therapies: real-world evidence from three datasets. Poster presented at: ASCO 2015 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; February 26-28, 2015; Orlando, FL. Available at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/141595-159. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzpatrick JM, Bellmunt J, Fizazi K, et al. Optimal management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: highlights from a European Expert Consensus Panel. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(9):1617-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM.. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15(5):615-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Satkunasivam R, Kim AE, Desai M, et al. Radical prostatectomy or external beam radiation therapy vs no local therapy for survival benefit in meta-static prostate cancer: a SEER-Medicare analysis. J Urol. 2015;194(2):378-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong WL, Evans SM, Spelman T, Kearns PA, Murphy DG, Millar JL.. Comparison of oncological and health-related quality of life outcomes between open and robot-assisted radical prostatectomy for localised prostate cancer - findings from the population-based Victorian Prostate Cancer Registry. BJU Int. 2016;118(4):563-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcia-Albeniz X, Chan JM, Paciorek A, et al. Immediate versus deferred initiation of androgen deprivation therapy in prostate cancer patients with PSA-only relapse. An observational follow-up study. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(7):817-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Backus LI, Belperio PS, Shahoumian TA, Cheung R, Mole LA.. Comparative effectiveness of the hepatitis C virus protease inhibitors boceprevir and telaprevir in a large U.S. cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(1):93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westin GG, Armstrong EJ, Bang H, et al. Association between statin medications and mortality, major adverse cardiovascular event, and amputation-free survival in patients with critical limb ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(7):682-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kranz AM, Rozier RG, Preisser JS, Stearns SC, Weinberger M, Lee JY.. Comparing medical and dental providers of oral health services on early dental caries experience. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):e92-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao Y, Abrahamowicz M, Moodie EEM.. Accuracy of conventional and marginal structural Cox model estimators: a simulation study. Int J Biostat. 2010;6(2):Article 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J. The t test for means. In: Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1977:19-74. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin PC. Using the standardized difference to compare the prevalence of a binary variable between two groups in observational research. Commun Stat Simul Comput. 2009;38(6):1228-34. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone versus placebo plus prednisone in chemotherapy-naive men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (COU-AA-302): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):152-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hussain M, Tangen CM, Berry DL, et al. Intermittent versus continuous androgen deprivation in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1314-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sonpavde G, Bhor M, Hennessy D, et al. Sequencing of cabazitaxel and abiraterone acetate after docetaxel in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: treatment patterns and clinical outcomes in multicenter community-based US oncology practices. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13(4):309-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gauthier H, Bousquet G, Pouessel D, Culine S.. Abiraterone acetate withdrawal syndrome: does it exist? Case Rep Oncol. 2012;5(2):385-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witjes JA. A case of abiraterone acetate withdrawal. Eur Urol. 2013;64(3):517-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caffo O, Maines F, Trentin C, Veccia A, Galligioni E.. Long-term outcomes and predictive factors in patients (pts) with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) showing abiraterone withdrawal syndrome (AWS) after docetaxel (DOC) treatment. Poster presented at: ASCO 2016 Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; January 7-9, 2016; San Francisco, CA. Available at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/157891-172. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crona DJ, Whang YE.. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome induced by enzalutamide in a patient with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2014;33(3):751-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Langston B, Armes J, Levy A, Tidey E, Ream E.. The prevalence and severity of fatigue in men with prostate cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(6):1761-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith JA, Soloway MS, Young MJ.. Complications of advanced prostate cancer. Urology. 1999;54(6):8-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, et al. Antitumour activity of MDV3100 in castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1-2 study. Lancet. 2010;375(9724):1437-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sternberg CN, Molina A, North S, et al. Effect of abiraterone acetate on fatigue in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(4):1017-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pilon D, Ellis LA, Mckenzie S, Gozalo L, Lafeuille M, Lefebvre P.. Central nervous system conditions in abiraterone or enzalutamide-treated prostate cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15 Suppl):Abstract e16067. Available at: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/149602-156. Accessed October 22, 2016. [Google Scholar]